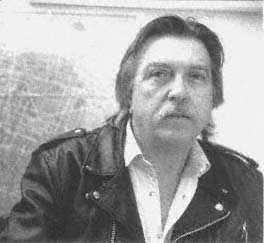

Joseph Guglielmi

Joseph Guglielmi was born in 1929 in Marseille. Among his many books of poetry are Aube (Paris: Seuil, 1968), Pour commencer (Paris: Action poétique, 1975), Le Jour pas le rêve (Paris: Orange Export, Ltd., 1977), Du blanc le jour son espace (Nîmes: Editions Terriers, 1979), La Préparation des titres (Paris: Flammarion, 1980), Fins de vers (Paris: P.O.L., 1986), Das, la mort (Marseille: Parenthèses, 1986), Le Mouvement de la mort (P.O.L., 1988), Poésie, poésie (Paris: Jean-Luc Poivret, 1990), Joe's Bunker, suivi de L'Eté (P.O.L., 1991), and K ou Le Dit du passage (P.O.L., 1992). He has written two works of criticism: Le Dégagement multiple (Paris: Le Collet de buffle, 1977) and La Ressemblance impossible: Edmond Jabès (Paris: Editeurs français réunis, 1978).

Selected Publications in English:

Ends of Lines , extract. Translated by Michael Palmer and Norma Cole. o·blek[*] 5 (Spring 1989): 131–36.

Le Mouvement de la mort , extracts. Translated by Norma Cole. In Violence of the White Page: Contemporary French Poetry , edited by Stacy Doris, Phillip Foss, and Emmanuel Hocquard. Special issue of Tyuonyi , no. 9/10 (1991): 103–6.

"Passing." Translated by Serge Gavronsky. Shearsman , n.s., 6 (1992): 7–9.

"Passing" and extract from "Joe's Bunker." Translated by Serge Gavronsky. Hot Bird MFG 2, no. 6 (1993).

Serge Gavronsky: I've always been struck by the energy that arises from your work, which is rather rare in contemporary French poetry. Were I to generalize, I might even say that you are a unique phenomenon in French poetry since, judging from the texts of yours that I've read and the opportunities I've had to hear you read in public, the nature of your voice sustains the decision in your poetry to exist as an electrifying experience.

Joseph Guglielmi: That compliment, my friend, goes right to my heart! I don't think energy is the result of a particular decision; it's rather like an electric current that either passes through or doesn't. But I would still have to say that language itself, in its natural state, already contains an energy charge. Between words, in order for them to make sense, in order for meaning to occur, there must be some sort of energy; without it, there's no poetry, there's no language.

SG: As you know, since you're a reader of American poetry, at least in a certain kind of American poetry the oral aspect is preponderant. There is a "performance" factor, an insistence on the polish of the delivery, a concern for public reception of works read out loud to an audience. I believe this sort of practice carries over into the content of the work itself since, consciously or unconsciously, the poet begins to "hear" his or her poetry, an experience which then, at least in part, dictates the nature of his or her poetry and constitutes a sort of updated Whitmanesque poetics, as opposed to both a Wallace Stevens strand and what is referred to as "academic" poetry in the U.S. This emphasis on the projected voice, on orality, as typified by the Beats, seems to me to have pushed écriture into the background. Would you talk about the place of that vocal quality in your work?

JG: At least two stages have got to be taken into account in answering your question. The first one is the writing, and perhaps in that first stage there is already a foreshadowing of orality. For example, in my Fins de vers , I tried to write using an eight-foot line, a rhythmic eightfooter, not rhymed, of course! And when I read it out loud I try to discover this rhythm in the writing, and I find it and at the same time transform it, increasing its tension so as to underline the scansion.

When I scan the lines, I try to give them maximum energy (as you've noted), an expressive energy. I'm not adding meaning but expression, to make the reading more "brawny"! That way, the line communicates to the listener through a tension, a scansion.

SG: In La Préparation des titres , it's clear you like to insert lines from foreign languages, especially English, into your French poem. What does their presence correspond to? Even readers who do not understand a foreign language must, I imagine, be struck by this insertion, and for those who do understand, it is an added semantic and phonic attraction. Could you talk about the way these insertions function in your writing?

JG: If I might answer in two ways, the first would simply be that I like doing it, that it's fun! But in a more serious vein, let me add that, as you know, I've been translating American poets such as Larry Eigner, Rosmarie Waldrop, Clark Coolidge, and at this moment, an American poet living in Paris, Joseph Simas. This linguistic activity, that is, translation, gives me a great deal of pleasure, even if at times it makes me sweat! To answer your question then, sometimes I simply use these languages—I was about to say that I stuff them, but I'll say I place them in my work, I use them to articulate my texts. Sometimes when I put an American line in my poem it adds an even greater element of energy, because English, for me, is a very musical language. All you have to do is listen to a blues singer, or even a Shakespearean actor . . . There's a special musical quality that really touches me, and I try to pepper my own verse with it a bit, for a little more energy, power.

SG: When you translate American poets, to say nothing of your translations from the Italian, do you feel a difference, one that's only noticeable to the translator, a difference between the nature of the English language and the presence of the French—that is, when you go from English to French, do you feel a loss, an enrichment, a displacement?

JG: When I go from English to French I often feel a loss. First of all, as I've just said, there's a loss of musicality and also a loss on the level

of expression. There's a relief in English writing, a force, an energy (to use the word again) that is often lost in French, although something else may be gained. But that musicality is lost, and I would say the same thing for Italian. I once attended a meeting of poets at the Pompidou Center—there was a Russian poet, an American, and many French poets. But let me tell you, I was really struck by how flat French sounded beside the Russian and American readings! I'm certainly not asking for a bel canto , but there wasn't that song, that sort of folly that those other languages convey. Unfortunately, French has a rather flat musical line. It's a flat language. You know, in the south of France, when you talk like a northerner, like a Parisian, they say you're talking "sharply," "pointedly." And I certainly don't have that accent! [Guglielmi has a strong southern accent.]

SG: I agree with what you're saying, though I know poets in Paris who are quite happy with this restriction that the French language imposes on their work and who, as a consequence, concern themselves with problems of écriture rather than the breath line in poetry. The type of reading you mentioned, at times a bit flamboyant, is rarely found among Paris poets, although a certain fellow by the name of Artaud clearly wanted to break with that tradition!

JG: Not to be unjust, I should point out that work on language is also very important for me. Like you, I too have been very interested in both Francis Ponge and Edmond Jabès. This questioning of language by language itself (if I might simplify a bit) is really the essence of poetry. Alongside that, I do raise the problem of public diction, which is a specific problem and one that characterizes my own work, but for all that, I certainly don't neglect the work on language, which is the poet's work as found in Jacques Roubaud, Claude Royet-Journoud, Anne-Marie Albiach, Jean Daive, and others. These are people who are interested in all the problems of diction, including public readings. Perhaps they don't ask the same questions I do, but they do, quite insistently, ask similar ones.

SG: You've just alluded to Jabès, and I know that you've written about him . . .

JG: A whole book, even!

SG: Right, sorry! With Jabès, who is a poet—that is, he wrote poems during his early years in Cairo—there is something that has always struck me as an apparent paradox; namely, he seems to be a materialist metaphysician, someone who asks questions about Judaism, about Being, Exile, and the Desert, all the while insisting, with equal conviction, on the lives lived by ordinary human beings in their own milieus. As a consequence, his language is at once "philosophic" and current, a spoken language that one might easily associate with prose. He's marvelously able to synchronize these levels of language, which indicate to the reader separate and apparently distinct preoccupations. But when I think of some of the poets we know, I do not see a similar complexity of intention, and when the question of Being is raised, it seems to be too psychoanalytically motivated, that is, too autobiographical—even, and perhaps especially, when it is defined in a post-Mallarméan enterprise. Are you yourself touched by some of these themes, by some of these translations of themes into a working poetic language?

JG: All these questions are of special interest to me, and at this moment I'm preparing a paper on Jabès that I'll be giving at the Cerisy "Décade" in his honor this summer (1987).[*] But I think what touches me most in Jabès is his subversiveness. He speaks about Judaism, but—and isn't that one of the traits of Judaism, that is, to be subversive?—he exercises an option in interpreting important Jewish texts, interpreting them rather freely, and . . . isn't it always the same thing—if you're an asshole, you'll come away with an asshole interpretation! If not, then not. I find that Jabès has given the question of Judaism an absolutely subversive interpretation, and I'm certainly not the only one to have said this. Didn't he title one of his recent books Subver -

[*] The "Colloque de Cerisy-La-Salle" in 1987 honored at its traditional ten-day conference the Egyptian-born French poet and writer Edmond Jabès (1912–91). See Joseph Guglielmi, "Le Journal de lecture d'Edmond Jabès," in Ecrire le livre: Autour d'Edmond Jabès (Seyssel: Champ Vallon, 1989). Guglielmi had previously written the afterword to the second edition of Edmond Jabès, Je bâtis ma demeure (Paris: Gallimard, 1975), 325–33.

sion above Suspicion ?[*] And so, with Judaism as his starting point, Jabès questions écriture, politics, ethics, aesthetics. I think he confronts nearly all the great questions that exist and, though they will never be resolved, remain fundamental.

[*] Edmond Jabès, Le Petit Livre de la subversion hors de soupçon (Paris: Gallimard, 1982).

Joe's Bunker

My own bunker is you

because poetry isn't

a bunker, but for some

poetry is a bunker,

For me a godsent spring[*

] and joyous omens, sic

of musical translations

oblivions for legs and feet.

Or private public recourse

suborning the music so

music private public

Almond paste shaped like moons

of tradition the muddy flow,

dreamy dreamer, running grey

is deathless or immortal

reading black space motions of ghosts

[*] Italics indicate words written in a language other than French in the original poem.

the moon over the bunker

like a hat over a heart

And dialogue with monsters,

sirens who hide

in the black black of the sea sea.

In the incessant myth-ocean

its level graft of moon

versified in French for his

pains; catalog cut out

an adieu, mental punctuation

like, like YOGADRISHTI

Yoga power of vision.

The earth beauteous belle, clear

Beauty clear and fair the air

Bunker makeup of your mouth

Hand playing with spare scorpions,

impaled by a million lives.

And the white lollipop stick,

of the rotting, stupid moon

Fish rotting head to tail,

shit-debris of the mind,

A nice day in the universe

scrutinized naked in the mirror ,

mirror of angels' dust

The cavalcade, fragment of a word

or metaphysical moon

On that thing of an airport

between thighs and a bud

its vernacular clarity

Moon like cream in my coffee,

moon bunker of space

Abandoned full moon

post the worthless line

on the facade of old summer

Scheming

the company

Bunker, Seven Songs of Hell

bloated belly and naily hands,

Screaming rain with mutts,

thrown into mealy mouths,

Iron river under trees,

hands, vein music

press the blood upward

Blush at moments of love

or pick up an old poem

With breasts in the shape of a

cross, cut the lines

shorter

to attract

attention!

Pilot the flesh further

Injustice for Eliot

Quis hic locus, quae regio ,

what tongue tonguing the

prey

and what image returns ?

Those who exhaust the line,

their pigsty comfort

in the style of contentment!

Establishment of death,

the heart, the body, the eye.

What a picture, the punster,

awake, half-open lips.

To live for the inexpressible!

The bodies you can touch

in the bunker of the flesh

Real words in your body

already asleep, you are alone

near the sea of Albisola

or any sea!

So recently churned over.

The island

Pentacle trembling

Its body, an enormous octopus

with its humid breasts . . .

Breasts, milkwood,

The sign Mahamudra,

bunker lips

in the center

flatter their color circle

After a smoked rose

or a belly liquor drunk

The frog leaping out of void .

How

to hold the poem,

typecase where the mind

and sleep join till black?

Bright night. A strip

of flesh, the city reflected,

and forms erected in fear

Everything holds on the flat sky

in a Reverdy figure

that flames made bleed

the bunker of the hollow moon,

grating metal on the horizon.

An enamel cascade

and cold through its handsome body

Continue to seek out

karma isn't a bunker

Or energy escapes us,

universal difficult !

Too body, body, body !

Our will the instru

ment of a struggle against the

book-bunker or mother's milk!

Take the one Under Milk Wood

drinking all the earth's alcohol

yelling out his kisses in verse

some of them long but are so

rhythmical leaping and dancing

between the stars and the chimneys

Spawn of the living art and mind

Sharp moments of the language

unlocking the secret, piercing

the night

black torch in sunrise ,

When poets are in bed

soft and white in their skins

enjoying the sun in bed

rhythms leaping and dancing

between star and chimney

Tulips also

moments

sharpened moments of language

to free the secret,

Black torches at the dawn

of verse horizon of meaning,

displacement of the map

a couple of letters with sla

shes of anterior lives,

A lightness next to writing

a tongue loosened,

Tongue in pidgin italian

or the autopsy of chance

Gusto della tua saliva

con il fuoco sulla bocca

Scan those plaintive sounds

il lamento fra i cocci .

And that maritime town

so long ago out of you

man of invisible nights

colors having passed

All his wrongs and his reasons:

Solo nella stanza vuota ,

hollow and which spoke to the dead.

There would be a final book,

metonymic light

its

prosaic reservoir

brilliant with a muted luna ,

tiny lux and the ball

with an encaustic sky

and

train noise in firmament

Joe's Bunker

Mon bunker à moi c'est toi

car la poésie n'est pas

un bunker, mais pour certains

poésie est un bunker,

For me un printemps d'aubaines

et joyeux augures, sic

de traductions musical

oblivions for legs and feet.

Or private public recourse

suborning the music so

musique privée publique

Amandes en pâte de lune

de tradition le flot boueux,

rêveur, rêvasseur, running grey

is deathless or immortal

reading black space motions of ghosts

la lune sur le bunker

comme un chapeau sur un coeur[*]

Et dialogue avec les monstres,

les sirènes qui se cachent

au noir noir de la mer mer.

Dans l'incessant mythe-océan

son niveau enté de lune

mis en vers français pour sa

peine; catalogue creusa

l'adieu, mental ponctuation

comme, comme YOGADRISHTI

Pouvoir yoga de la vision.

La terre belle beauté, clear

Beauty clear and fair the air

Bunker de ton fard de bouche

Main joueuse de scorpions secs,

empalés d'un million de vies.

Et le bâton blanc de sucette

de lune stupide, pourrie

Le poisson de la tête-bêche,

le débris-merde de l'esprit,

A nice day in the universe

à nu scruté dans le mirror,

miroir poussière des anges

La cavale, un fragment de mot

ou lune métaphysique

Sur le truc aéroport

entre les cuisses et le bud

sa clarté vernaculaire

Lune comme un café crème,

lune bunker de l'espace

Abandon de lune pleine

afficher le vers indigne

au fronton du vieil été

Machiner

la compagnie

Bunker, Sept Chants de l'Enfer

ventre large et mains onglées,

Pluie hurlant avec les clebs,

jetés dans les bouches bouchues,

Un fleuve de fer sous les arbres,

les mains, musique des veines

presser le sang vers le haut

Rougir aux moments d'amour

ou reprendre un ancien poème

Vec les seins en forme de

croix, couper les vers

plus courts

pour attirer

l'attention!

Piloter la chair plus loin

Injustice for Eliot

Quis hic locus, quae regio,

quelle langue léchant la

proie

and what image returns?

Ceux qui épuisent le vers,

leur porcherie de bien-être

in the style of contentment!

Establishment de la mort,

le coeur[*] le corps, le regard.

Quelle image, le faiseur,

l'éveil, lèvres entrouvertes.

Vivre pour l'inexprimé!

Les corps que tu peux toucher

dans le bunker de la chair

Les mots réels dans ton corps

dorment déjà, tu es seul

près de la mer l'Albisola

ou n'importe quelle mer!

Tout fraîchement retournée.

L'île

Pentacle tremblant

Son corps, une énorme pieuvre

avec ses gorges humides . . .

Une gorge, bois de lait,

Le signe Mahamudra,

bunker des lèvres

au centre

flatter leur cercle couleur

Après une rose fumée

soit liqueur du ventre bu

The frog leaping out of void.

Comment

tenir le poème,

casseau où joindre l'esprit

et le sommeil jusqu'au noir?

La nuit qui brille. Une lame

de chair, la ville reflet,

et formes dressées dans la peur

Tout se tient sur le ciel plat

à figure Reverdy

que la flamme faisait saigner

le bunker de la lune vide,

métal qui grince à l'horizon.

Une cascade d'enamel

and cold through its handsome body

Continuer à chercher

le karma c'est pas a bunker

Ou l'energy nous échappe,

universelle difficult!

Trop body, body, body!

Notre volonté instru

ment de lutte contre le

livre-bunker ou loloche!

Prenez celui Under Milk Wood

buvant tout l'alcool de la terre

criant ses baisers en vers

plus ou moins longs but are so

rhythmical leaping and dancing

between the stars and the chimneys

Spawn of the living art and mind

Sharp moments of the language

unlocking the secret, piercing

the night

black torch in sunrise,

Quand les poètes sont au lit

douillets et blancs dans leur peau

jouir du soleil au lit

rythmes sautés et dansés

entre étoile et cheminée

Tulipes aussi

moments

moments aiguisés du langage

pour débloquer le secret,

Noires torches à l'aurore

du vers horizon du sens,

déplacement de la carte

quelques lettres avec jam

bages de vies antérieures,

Légers à côté d'écrire

d'une langue déliée,

Tongue in pidgin italian

or l'autopsie du hasard

Gusto della tua saliva

con il fuoco sulla bocca

Scander ces sons à la plainte

il lamento fra i cocci.

Et la ville maritime

si longtemps sortie de toi

homme des nuits invisibles

des couleurs ainsi passées

Tous ses torts et ses raisons:

Solo nella stanza vuota,

vide et qui parlait aux morts.

Il y aurait un dernier livre,

lumière métonymique

son

réservoir prosaïque

brillant de muette luna ,

petite lux et la boule

avec le ciel encaustique

et

bruit de train in firmament