Chapter Three—

Midpriced Mansions for Middle Incomes

Retail sales managers did not generate headlines and society page gossip as did the heiresses and silver kings who lived in palace hotels. However, twice as many people of middle incomes lived in downtown hotels than wealthy people who lived in palace hotels.[1] These less-expensive hotels supplied housing needed for a mobile professional population that was expanding the American urban economy. Compared to their wealthier counterparts, middle-income hotel residents shared many values and advantages in hotel life, but they lived in hotels less for social reasons and more for personal and practical reasons. The midpriced hotel was an alternative choice of residence for people whose lives did not mesh with a six- to ten-room single-family suburban house.

Convenience for Movable Lives

Like palace hotel life, midpriced hotel life began in the early 1800s. In the young Chicago of 1844, about one person in six listed in the city directory lived in a hotel, and another one in four lived in a boardinghouse or with an employer.[2] Walt Whitman reported in 1856 that almost three-fourths of middle and upper class New Yorkers were either

boarders or permanent hotel guests. When Whitman asked one little girl where her parents lived, she answered instructively, "They don't live; they BOARD."[3] Through the 1890s, visiting writers from London emphasized that (compared to the English) many more Americans could buy a modest house of their own but preferred to live in boardinghouses and hotels. American writers concurred. One remarked about the "temptation to live in hotels instead of in apartment houses." In 1919, the sociologist Arthur Calhoun explained that hotel life might begin in a couple's youth and continue through their mature years or be resumed after a period of housekeeping. He wrote that "almost any family, even the wealthiest, might at some time try this manner of life."[4]

Immediate Places for New Job Holders

The occasional shortage of single-family houses in rapidly growing cities was one factor that sent middle-income families who were new to a city to a hotel. House prices and mortgage terms were high. Also, from 1870 to the 1920s, the building of new suburban houses did not consistently match demand. Families waiting for a house often lived in a hotel for a year or more. In 1880, the family of San Francisco stockbroker Daniel Stein (including his daughter Gertrude Stein) lived for over a year in a suite in a commodious wooden hotel in Oakland while they waited to move a dozen blocks away into a suburban house with a ten-acre garden (fig. 3.1).[5]

Temporary jobs created other middle-income hotel dwellers. From the Civil War through World War II, people in rapidly expanding business markets were often sojourners. The expansion of trade and railroad links throughout the United States opened thousands of white-collar positions in manufacturing, marketing, and managing chain store and branch store businesses. Engineers, accountants, lawyers, and other professionals flocked to assist these new operations.[6] Many people very tentatively began their stay in a new company or city; they expected to live there only for a period of a few months to two or three years. Such sojourners made up a significant share of the permanent residents in midpriced hotels, and their initial visit often stretched into lifelong hotel residence.

Epitomizing the sojourner household were Mr. and Mrs. Walters, a couple interviewed in the 1920s. They had lived in hotels in small cities near Chicago for a succession of years. In each place, Mr. Walters spent

Figure 3.1

The Tubbs Hotel in suburban Oakland, soon after its opening in 1871. Gertrude Stein's family lived here

while waiting for completion of their house two miles away.

four or five months establishing a branch sales department for electrical appliances; then he placed a sales person in charge and moved to another town.[7] Similarly, construction projects required experts who stayed for months or years of planning and building. Architects flocked to cities after major fires, then moved on a few years later. It was not unusual for sojourning architects to live in hotels; in a few cases, they also set up offices in the same building. Louis Sullivan's life was not as peripatetic as some of his lesser-known colleagues, but the famous architect lived in hotels much of his life.[8] Because of their centrality, hotels made ideal temporary office sites. In certain midpriced hotels, traveling sales people set up temporary offices in sample rooms purposely built and reserved for the display of wares. Some business people rented rooms in a residential hotel in the winter simply to avoid cold-weather commuting from their houses in distant suburbs. People serving on temporary government or business committees also relied on hotels in the midprice range.[9]

Figures 3.2 and 3.3

The problem of hotel noise, 1871. The Harper's Weekly cartoonist Thomas Nast

emphasized the risks of hallway interruptions especially where permanent

residents were not separated from tourist rooms.

For sojourners in a new city, moving into a hotel simplified the housing search. Hotels required commitments of only a month (at most), rather than the long-term leases required of apartment and house renters. Another inherent advantage of hotel life was avoiding the packing and lugging of household goods and large pieces of furniture. As one hotel observer put it, when a family had to move frequently, "even a large wardrobe is a nuisance, and a collection of furniture would be as appropriate as a drove of elephants."[10]

Like palace hotel residents, residents in midpriced hotels were well positioned to weave themselves into the social groups they needed for their work or personal ambitions. Hotels combined central location, maximum information availability, and high potentials for human contact with influential people of the middle and upper class. Hotel lobbies and dining rooms—in the early nineteenth century the official stock exchanges in many cities (and official slave markets in the South)—were alive with business and gossip. In other hotels, informal and openended social groups formed around billiards, dice, and card tables. In the 1920s, one young hotel resident wrote that her businessman father fortuitously met many other men of affairs in the lobby and in the smoke-filled billiards room after dinner.[11] Not all social aspects of hotel life were positive, but for a distinct minority of households, the advantages outweighed the problems (figs. 3.2, 3.3).

Assists for Politicians and Young Couples

Given these virtues of centrality, sojourning politicians naturally made up a significant hotel residence group. Through the 1800s, each urban political party patronized a particular hotel, and politicians to this day often live in capital city hotels while legislatures are in session. When owners tore down the old Neil House in Columbus, Ohio, President Warren Harding wrote to the managers saying that the hotel had been the "real capitol" of the state. Huey Long maintained a suite at the elegant Fairmont Hotel in New Orleans, spending so much time there that Louisiana lore suggests that he built State Highway 61 from the state capitol directly to the door of the hotel for his own convenience.[12] The most famous hotel-dwelling politician was Calvin Coolidge. The thrifty Coolidge and his wife were very long term hotel tenants. They lived many years in a dollar-a-day room in the old Adams House of Boston (built in 1883). When Coolidge was elected governor of Massachusetts in 1918, on the advice of friends he moved into a $2-a-day room. In 1921, Vice President and Mrs. Coolidge moved into the same modest fourth-floor corner suite in the Willard Hotel that Vice President and Mrs. Thomas R. Marshall had occupied throughout Marshall's second term in the Wilson administration. In 1922, a Washington hostess tried unsuccessfully to establish a pretentious vice-presidential house. Coolidge himself quelled the move, saying that maintaining such a residence on a $12,000-a-year salary was out of the question. The Coolidges remained in their Willard Hotel suite.[13] More recently, Supreme Court Justices Felix Frankfurter and Earl Warren have lived in hotels.[14] For most of 1931 to 1934, early in his career in Congress, Lyndon Johnson lived at the Dodge Hotel in Washington, D.C. During the early years of the Reagan administration, Attorney General William French Smith and Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger settled at the Jefferson Hotel.[15]

Newlyweds often lived in hotels. In the last half of the 1800s, people considered it unremarkable when a young couple lived the first two or three years of their marriage in a good boardinghouse or hotel. Such a life could be just as respectable as residence in a private house. In 1879, Sala noted that American married couples lived in fine hotels "by the half-dozen years together." Young married couples made up the mainstay of the guests in many expensive hotels, and teenage wives became the most numerous female residents.[16] At least until the 1890s, young well-to-do and middle-income brides often relied heavily on hotel so-

ciability. In a time when the median age for women at marriage was twenty-two to twenty-four years, younger brides could move into a hotel and enjoy the familiar routine of courting days and the company of young friends. They could spend a major part of their days visiting one another in their rooms or in the public parlors, either mimicking the formal visiting of residential neighborhoods or merely gossiping. According to the social historian Robert Elno McGlone, the conviviality of hotel life relieved women's fears of "early fading" or being "laid upon the shelf," phenomena they saw in many hardworking young wives and mothers who toiled at keeping house. For wives whose husbands traveled a great deal, hotel sociability also made life less lonesome than life alone in a house or an apartment.[17]

Young couples or single people—especially those accustomed to a high standard of living in their parents' homes—could more easily match or improve those standards by living in a palace hotel or midpriced hotel than by buying the expensive furnishings for a private house. Up to the 1890s, there were apartments for the very rich but a less ready supply of socially respectable apartments geared to middle incomes. Hotel managers catered to these desires for an impressive domicile; the plush furnishings in a good midpriced hotel could cost about half as much as the building itself. A traveler in 1855 observed that the better boardinghouses and almost all hotels were "furnished in a far more costly manner than a majority of young men can afford"—in fact, a life-style that would have cost twice as much in an individual household. This continued to be true into the 1920s. In 1926, a conservative estimate for the cost of complete furnishings for a professional person's household, with no servant and only an upright piano as an extravagance, totaled $5,000.[18] Such an initial cost, spread out in monthly rentals, bought far more sumptuous surroundings in a hotel.

Monthly rental costs in a midpriced hotel were usually one-half to one-third the rates at palace hotels. A Chicago sociologist, Norman Hayner, compared costs in the mid-1920s and found that a single room with bath at a midpriced hotel usually ranged from $40 to $60 a month. Hotel managers almost never advertised or divulged monthly rents charged to tenants, since they were individually negotiated. For permanent guests, monthly rates were always less than four times the weekly rate; sometimes they were only two weeks' rent for a month of occupancy.[19] For single people who did not have a servant or a family

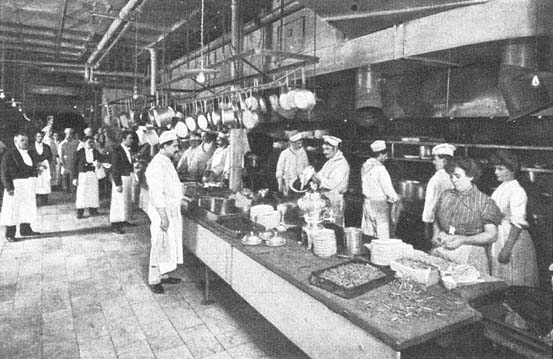

Figure 3.4

The core of cooperative housekeeping. A hotel's kitchen and serving staff pictured in Cosmopolitan

in 1905.

member to perform food preparation and housework, these prices were a bargain. As late as 1909, social workers admitted that it "nearly always" cost more "time, effort, and money to live well in suburbs than in town." Three Chicago schoolteachers explained to Hayner that separately they had been paying $6 or more per week for rooms with individual families. By pooling their rent money for a large room in an elegant midpriced hotel, they each saved a dollar a week and lived far more conveniently and convivially.[20]

New Household Roles for Women

Cooperative housekeeping was the hotel attraction appreciated most by middle-income people. None of the men in hotels had to fix the furnace, repair the windows, fertilize the garden, or mow the lawn. The most enthusiastic people being set free from housekeeping were women who wanted to take an active part in city life or whose employment left them too little time for housework. In a hotel household, none of the women needed to shop for food, cook it, serve it, or wash the dishes (fig. 3.4). Laundry, housecleaning, and decorating were also commercialized. Wealthy women avoided the "servant problem" of hiring, supervising, and firing their

cooks, maids, and butlers; middle-income women avoided the supervising problems of one or two servants and also their own share of the housework. However, an early observer wrote that the convenience and amplitude of hotel meals were the "strongest attraction the hotel offered." Destroy the meal plan and the families would form private households, he added.[21] Before the 1920s brought revolutions in food processing and packaging, assembling the raw, unprocessed ingredients to feed even a small middle-income family demanded myriad errands and consumed many hours. Feminists like Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Christine Herrick looked forward to the days when housekeeping schools would train skilled, professional home labor and when hot dinners would be cooked at central kitchens by salaried employees. They wrote that such arrangements would give domestic service "dignity and independence, and a scientific quality"; such a business would be "a sort of Adamless Eden, run for and by women." In the meantime, hotel and apartment hotel life freed women from what the writers saw as the drudgery and humiliation of unpaid and undervalued cooking and housework and the waste of "a hundred fires being run to cook a meal instead of one, a hundred cooks, where six could do the work."[22]

By the 1920s, in part because hotel service freed them from housework, women often predominated as residents in midpriced hotels, although the proportions varied considerably with the district of the city. In the 1930 U.S. Census of Chicago, areas with large numbers of residential hotels showed about three women to every two men; in the larger, more transient hotels in the Loop, the proportions reversed. Of the married women in several fairly expensive midpriced hotels of the 1920s, only 2 to 10 percent worked for monetary return. The rest, according to one study, had "interests in charities and social reform or were simply 'mental rovers.'" In Seattle, two-thirds of the women in midpriced hotels lived alone, and most of them worked if they were below retirement age. The working women in the better hotels were predominantly teachers, buyers in department stores, executives in other businesses, writers, librarians, private secretaries, social workers, or women politicians. Showing the common social or professional congregation that occurred in residential hotel life, in one large downtown hotel in Seattle, 60 percent of the four hundred guests were women, and almost 25 percent of them were schoolteachers. Many of these women were not merely sojourners. Married or not, they were escaping

female roles in traditional households and fully expected to live in hotels for at least several years. A journalist writing in 1930 characterized these people as the vanguard of the "new woman."[23]

Self-preserving Associations

Exclusion or discrimination also pushed some middle-income people to live in hotels. Jewish people figured prominently in some midpriced residential hotel markets. In The Ghetto (1928), Lewis Wirth stressed that predominantly Jewish hotels had become the latest avenue of escape from some Jewish neighborhoods. Wirth noted that in both Chicago's Hyde Park and North Shore districts, a "Jewish hotel row" had begun to spring up, inhabited by middle-income business people and their families. In the Chicago Beach Hotel, for instance, 80 percent of the tenants were Jewish. Wirth felt that housing in more Anglo-American hotels offered Jewish people a ready avenue for mixing with Gentile society, a residential proximity not then possible in most expensive suburbs.[24]

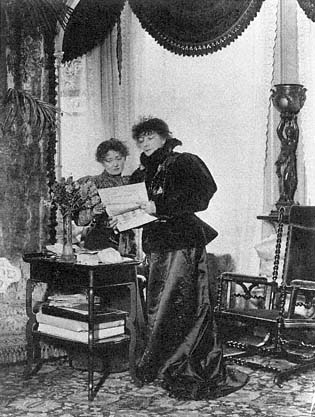

The mistrust of actors and artists as residents in other types of housing brought them, too, to hotels. "Born in a hotel and died in a hotel, Goddamn it!" were the dying words of Eugene O'Neill. Indeed, until automobile travel, radio, and movies restructured the American entertainment industry, sojourning theatrical troupes were often part of a hotel's residential composite. Unlike O'Neill (who lived in a house most of his life), star actors as well as bit-part players could spend most of their adult lives in hotels; headliners, in palace hotels. Sarah Bernhardt required an eight-room suite when she was performing in San Francisco (fig. 3.5). In less-expensive New York hotels have lived stars such as James Cagney, Tallulah Bankhead, Sammy Davis, Jr., Bill Cosby, and Cher.[25] Yet because of some actors' mobility, Bohemian moral codes, perpetual swing shift hours, and high divorce rate ("seven times the average for all occupations," clucked one newspaper reporter), actors and entertainers were not very welcome guests. Managers sometimes looked askance even at opera stars and symphony musicians. In cities with a population of more than 100,000, the less famous entertainers could find a budget-priced and slightly dilapidated "theatrical hotel." Chicago had six theatrical hotels in or near the Loop; hotel guides marked these hotels clearly, in part to warn other travelers.[26]

So many writers, editors, and composers made midpriced hotels their homes that they became another distinct client group. Artemus Ward

Figure 3.5

Sarah Bernhardt in her suite at the Hoffman House in

New York City, 1896. Among theater people, only

headliners could afford such expensive hotel homes.

lived in a hotel in New York's Greenwich Village when he came in the 1860s to edit the first Vanity Fair . Several writers made New York's Brevoort Hotel their home and through the 1880s mentioned life in the 100-room building in their novels. At New York's Majestic Hotel, at 72nd Street, another set of writers and artists congregated.[27] During two periods in her life, Willa Cather lived in a hotel: first, when she moved from Pittsburgh to New York City, and again in 1927, when building demolition forced Cather and Edith Lewis to move out of their apartment into the Grosvenor Hotel, at 35 Fifth Avenue. What they intended as a temporary refuge became their home for five years. Dylan Thomas and composer Virgil Thompson were only two out of many creative artists who made the Chelsea Hotel famous. Edna Ferber lived at the Sisson Hotel in Chicago. Nearer to the University of Chicago, Hannah Arendt and Thomas Mann each lived at the Windermere Hotel for part of their lives. Charlie Chaplin lived for a time in the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, and for almost fifty years the Am-

Figure 3.6

Advertisements for residential hotel life, 1936. Special monthly rates, social

activities, and good food were key promotional elements.

bassador was Walter Winchell's home.[28] The famous Round Table at New York's Algonquin Hotel met in the hotel dining room, but for the most part the members were not hotel residents.

Like most other downtown hotel residents, all types of creative artists thrived on hotel locations. These artists relied on and helped to support nearby restaurants, nightclubs, theaters, and other entertainments. A Gramercy Park hotel brochure in 1927 promised that its fortunate residents would "find themselves at the heart of the best New York can give."[29] Libraries, medical buildings, legal offices, and churches added to the downtown's convenience (fig. 3.6).

Retired and elderly middle-income tenants were also attracted to midpriced hotel life by the central access to recreation and downtown

services as well as the pedestrian independence hotels afforded. When the health of elderly hotel tenants waned, room service and hired nurses replaced their former independence. Throughout the history of inns and hotels, elderly people had been a proportion of the permanent residents.[30] Nonetheless, Sinclair Lewis's George Babbitt put retirement in a midpriced hotel in a dark light. Babbitt's in-laws had sold their house and moved to the Hotel Hatton in Zenith City, "that glorified boarding house filled with widows, red-plush furniture, and the sound of icewater pitchers." After a sad and soggy Sunday dinner, the Babbitts had to sit, "polite and restrained, in the hotel lounge, while a young woman violinist played songs from the German via Broadway."[31] Hayner's Chicago study gives the more positive example of the retired Martin couple, who had lived for twenty-five years in their own house in a small Illinois city and then for twenty-one years in various Chicago apartments. When their daughter married, the Martins moved to a hotel where they had often dined. Both of the Martins enjoyed dancing at the hotel. Mrs. Martin, an active woman in her late sixties, loved to be in the center of things and reveled in a crowd. When she was not in her room sewing for her nieces she was out shopping in the Loop.[32]

Not all hotel keepers wanted elderly tenants, healthy or not. "A nice old lady is nice," Ford said about elderly guests in his large midpriced hotel in New York, "but the average old lady is a troublesome boarder." Ford did not mention elderly men, but he continued, "When old ladies come to stay I don't try hard to cater to them. They go away. There's one hotel in town where most of them land."[33] Indeed, each city had several midpriced hotels with derogatory nicknames like "The Old People's Home" and coffee shops called "wrinkle rooms," even though no more than half of the residents at those hotels may have been elderly. Not all hotel residents were in such places. Kate Smith, for several years before her death in 1986, particularly liked to watch the ocean liners from her three-bedroom suite at the top of the Sheraton Motor Inn near the Hudson River and 42nd Street in New York.[34]

For all types of people, personal safety was a hotel attraction that many downtown apartment buildings could not match. Hotel desk clerks watched entrances around the clock; at intervals during the night, watchmen patrolled the halls checking for fire problems or situations amiss. When tenants had an emergency, staff were always on duty. People away from home overnight or for long periods of time

could leave with a sense that children, a spouse, or an elderly parent would be safer and have more readily available help than in a private home.[35]

Clearly, residents also came to live in midpriced hotels for emotional reasons as well as for practical and social advantages. The expanding local economies that helped to create jobs often meant an expanding supply of appropriate hotel buildings whose visual appeal, interior design, and gustatory delights helped to convince people to make the hotel their home.

Mansions for Rent

The palace hotels of the very rich were fabled realms, true palaces. Midpriced hotels were mere mansions, more common than palaces but several notches above the typical middle-income house. The builders and managers of midpriced hotels emulated palace hotels as much as their construction, decoration, and operation budgets allowed. Because they were building for less wealthy clients, midpriced hotel operators could develop many more hotels in many more places—from great cities of a million people to small towns with as few as 2,000 people—with the consistent theme of practical and affordable good taste.

The Classic Midpriced Hotel

In Victorian Chicago, the woman retailer who was a single parent or the enterprising New England mill representative and his wife might have chosen as their place of sojourn a building like Chicago's Hyde Park Hotel, built in 1887–88 (fig. 3.7). It had an open rectangle plan that left an ample light court for the inner rooms, a huge skylit lobby, and a first floor devoted to public rooms. Throughout the hotel were electric lights, telephone service, electric call and return bells, and steam heat for three hundred rooms arranged in two- and five-room suites. In the 1890s, many similar hotels labeled as "family hotels" or "private hotels" took few, if any, transient guests. Guests typically leased rooms by the year and decorated their rooms as they would a private house. Demand in San Francisco was such that applications for suites in new family hotels were often made six months before the building was finished. By the turn of the century, most large cities had rows of buildings with similar features on a few respectable streets or boulevards.[36]

Figure 3.7

The Hyde Park Hotel in Chicago, opened in 1887. It featured two-room to five-room suites and was

located at Hyde Park Boulevard and Lake Park Avenue. Photographed ca. 1928–1930.

By the 1920s, the most common suite in a midpriced hotel was two rooms, and use of those rooms varied. One occupant interviewed at that time had a parlor with a western exposure facing a park. He had brought in his own table, lamps, chairs, bookcase, and pictures. Elsewhere, a woman and her adult daughter shared a two-room suite. A Murphy bed in the parlor meant that at night each of them had a private room.[37] S. J. Perelman gave this graphic description of a single room in New York's Hotel Sutton, a midpriced residential hotel intended primarily for single people. The description could double for the modal midpriced hotel room:

The decor of all the rooms was identical—fireproof early-American, impervious to the whim of guests who might succumb to euphoria, despair, or drunkenness. The furniture was rock maple, the rugs rock wool. In addition to a bureau, a stiff wing chair, and a lamp with a false pewter base and an end table, each chamber contained a bed narrow enough to discourage any thoughts of venery.[38]

Had Perelman given a more complete furnishings list, he would have noted that the interior designer had specified the wing chair and its floor lamp in addition to a desk, a desk chair, and a desk lamp.

Perelman's room was not large enough for a dining table, which some larger midpriced hotel rooms had, but in many such hotels the guests could give dinner parties in private dining rooms near the lounges and lobbies.[39]

Midpriced hotel buildings could be very small (figs. 3.8, 3.9). Some, for instance, contained only twelve rooms (several with fireplaces, perhaps), all tucked within a 25-foot-wide building on a narrow downtown lot. At the other end of the scale, midpriced hotels could be notable structures of three hundred rooms with meeting facilities.[40] By the turn of the century, in hotels intended to have a mixture of permanent and transient guests, architects often included, off the lobby, a mezzanine floor with a more private parlor, sometimes including a piano, for the use of residents. These spaces probably evolved from the special ladies' parlors that most large hotels furnished through the turn of the century. The mezzanine floor offered conviviality with less overt supervision from the ground floor desk. Some residents also preferred hotels with side corridors to the street or cafeteria so they could avoid the public lobby and the routine surveillance of the hotel desk clerks.[41] Due to a series of public spaces reserved for them, especially before the 1930s, women in polite hotels could also have an experience of hotel life largely separate from men. Some hotels had a separate women's entry, different lounges, separate women's coffee shops, and different house rules. Likewise, the billiard room, barroom, and some lobbies and reading rooms were largely men's turf and off-limits to respectable women.

Degree of personal service and amount of plumbing distinguished the social rank of a midpriced hotel just as surely as the size and furnishings of the guest rooms. While palace hotels employed from one to four servants for each guest, one employee for every two guests was the norm in midpriced hotels through the depression. People on tight budgets who lived in hotels noticed that chambermaids went first to the larger, expensive suites and cleaned better there because those tenants could afford higher tips.[42] Plumbing saved on servant expense and drudgery, and more plumbing per room was particularly notable at the turn of the century. In 1875, the Palace in San Francisco had a bath for every room, but not until 1907 did a midpriced hotel make the claim of every room with a bath.[43] By about 1910, in midpriced hotels virtu-

Figure 3.8

Typical upper floor plan of the Ogden Hotel, Minneapolis, built in 1910.

Fairly large rooms, Murphy beds, and private baths helped to make

this a socially correct hotel for middle-income tenants.

Figure 3.9

Basement floor plan, Ogden Hotel, Minneapolis.

Note that the dining room (DR ) has a separate entrance from the outside

for nonhotel patrons. The kitchen (K ), pantries and storage rooms, and

an apartment for the manager (M ) filled out the floor.

ally every bedroom offered at least a room sink with hot and cold water. This provision had become common in private houses and hotels for the same reason: carrying water to the bedrooms was one of the onerous repetitive tasks required of the servants. In hotels of 1910, however, providing a full bathroom for every room was not yet common. About half the rooms had a private bath, and the rest shared hall bathrooms. Only by about 1930 did new hotels of this rank offer a private bath for every room.[44]

In small cities one building often had to serve as the equivalent of the town's palace hotel as well as its best midpriced hotel. Design guidelines for such hotels in 1930 noted that if 20 percent of the rooms had private baths, that was sufficient. Another 50 percent of the rooms were to have half-baths (basins and toilets), and the remainder of the rooms were to have simply room sinks and shared baths down the hall.[45] The hotel's date of construction often determined its precise bath ratio as well as the relative size of light wells and other amenities (fig. 3.10).

Figure 3.10

Comparison of typical 1907 and 1927 light wells in San Francisco.

Because the earlier building codes (right) had minimal

requirements, the light wells of midpriced hotels built

before World War I were much smaller than those

of a typical hotel of the 1920s.

Together, these features set the hotel's intended socioeconomic strata for at least its first generation of clients.

The plumbing and heating in midpriced hotels were often better than their counterparts in most private houses. In the mid-1800s, public rooms and corridors in hotels had steam heat; hotel bedrooms had individual stoves and fireplaces long before the bedrooms in average houses. Europeans soon began the tradition of complaining that Americans overheated their buildings. In later hotels most Americans first experienced the luxuries of indoor plumbing, push buttons, and iced or hot water readily on tap.[46] In the 1920s, such material comforts still contrasted sharply with life in most private houses. Residents of midpriced hotels of the jazz age repeated litanies of service and comfort heard only in palace hotels the generation before:

Life is luxuriously comfortable. . . . The idleness, the heat, the comfort [are totally unlike a family house]. . . . I have four towels each day, fresh sheets several times a week, hot water at any hour, lots of light and heat and a private bath. In the hotel are a restaurant, laundry, dry-cleaning establishment, bootblack, and many mail deliveries a day.[47]

Figure 3.11

Sunday dinner menu from the Hotel Beresford

in New York City, 1915.

Luxury, wrote one architect, was hotel living's outstanding characteristic and best drawing card; hence, attention to luxury was essential even in midpriced hotel design and especially in the public spaces.[48]

Large midpriced hotels always had an imposing lobby and a well-appointed dining room for full, leisurely, and fairly expensive meals (fig. 3.11). These spaces, along with the ballroom, bar, and breakfast room, were where the scale and social impressiveness of a public mansion could best be experienced. By the time of World War I, visitors could also expect to see the terms "café" or "coffee shop" used for casual lunchrooms in hotels. "The coffee shop idea," wrote a hotel kitchen expert in 1924, "seems to have completely uprooted the dairy lunch and cafeteria service of a few years back, and along with it the grill or grill range has replaced the long steam table."[49] Two residents on a tight budget told Hayner that they rarely used the elegant ground-

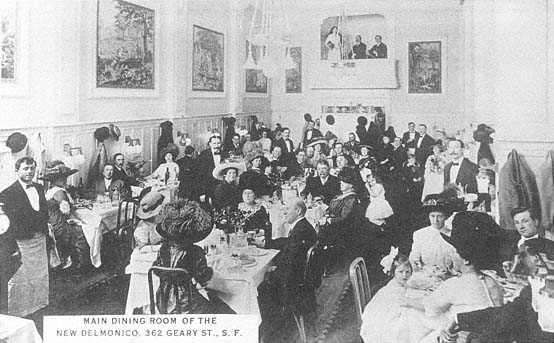

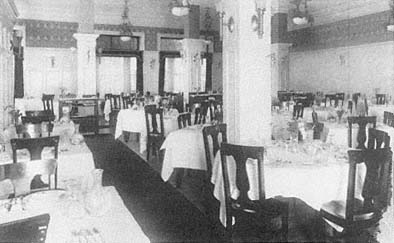

Figure 3.12

Postcard view of the Delmonico Hotel dining room, in San Francisco. The tall ceiling and musicians'

gallery set the tone for the room. European plan pricing allowed residents at midpriced hotels to sample

the fare at other restaurants.

floor dining room in their hotel but ate instead in the basement café. With food smuggled in from the outside, they also routinely stretched a room service meal for one into a meal for two. The smell of food illegally cooking on alcohol lamps or electric hot plates was known even in very fashionable hotels.[50] Many hotel managers eventually gave up the battle against long-term tenants cooking in their rooms and installed permanent hot plates or kitchenettes in some suites (depending on prevailing building codes). In the forty-nine largest palace and midpriced hotels in Chicago in the early 1920s, about 8 percent of the units were full apartments with a kitchen.[51] Also, the managers of midpriced hotels were among the earliest hotel keepers to give up the American plan of combined board-and-room payment. Instead, they offered rooms on either the American or European plan (fig. 3.12).

Even with the cheaper European plan prices, to live with hotel advantages people with middle incomes had to give up space. If they had been renting a suburban house or a respectable five-room apartment, they had to accept either a very small suite in a good midpriced hotel or a larger suite in a less elegant hostelry. Hayner writes of a family of four, with children aged three and eight, who paid $650 a month for their large house in a Chicago neighborhood that had lost its cachet;

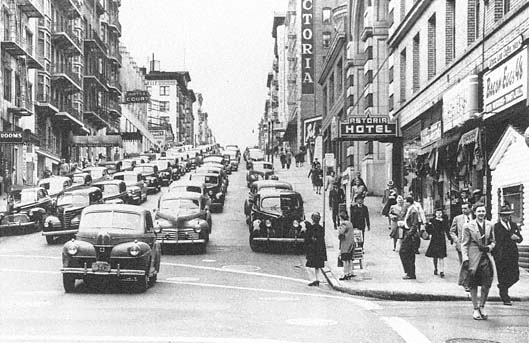

Figure 3.13

Bush Street near Grant, at the edge of a large midpriced hotel district in San Francisco, 1946.

While automobile drivers were stalled in traffic, hotel dwellers could always walk to work.

for $700 a month, they rented a small suite in a hotel on the fashionable Lake Michigan shore. He concluded that for families with incomes of at least $8,000 a year, hotels were cheaper than houses or large apartments of comparable social status.[52]

Links to the Tourist's and Shopper's Downtown

If the palace hotel was usually surrounded by some of the city's most exclusive boutiques, the midpriced hotel was usually close to the city's best department stores and reasonably close to the financial district. After 1910 in San Francisco, sojourners could find the most densely clustered midpriced hotels along Bush and Sutter streets between Powell and Jones. Depending on one's point of view, this small area was called lower Nob Hill or upper Union Square. The area contained almost a third of the city's midpriced hotel rooms and a large number of coffee shops and gift emporiums. Most hotels advertised for tourists, but they also listed themselves as "a home in a hotel" or "a residential hotel on an ideal residential street" (fig. 3.13).[53]

Although the self-image of the residents and hotel managers of these blocks revolved around the elites on Nob Hill, their daily lives revolved around Union Square. The square itself was a place to sit and watch

urban life. Nearby theaters and evening shopping lent a respectable nightlife to the streets. Grills and restaurants ranged in price from the expensive to the very cheap, making dining out easy and varied. It was a pleasant neighborhood for the middle-income person who wanted to be in the middle of the city's action.

According to the local myth, the hotels of Bush and Sutter streets, along with the nearby streets of the Tenderloin area, were built for tourists coming to the city's Panama-Pacific International Exposition in 1915. Every large city has similar rumors about the role of special events, and the rumors require debunking. Indeed, for midpriced hotels (and for palace hotels, too), travelers were always the primary market. In San Francisco, tourism became a major industry early in the city's history, and convention trade boomed with the advent of reasonable railroad rates. In 1897, the Southern Pacific Railroad helped to lure over 20,000 people for the Christian Endeavor Society convention. In 1904, the Triennial Conclave of the Knights of Templar brought 19,000 participants. These spikes of tourist dollars boosted the profits of hotels and other businesses more obviously than the steady stream of other travelers. In 1910, members of San Francisco's Chamber of Commerce announced ambitious plans for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, to be held in 1915. The exposition would celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal and prove that the city had fully recovered from its earthquake and fire of 1906.[54] As a direct result of the exposition announcement, many San Franciscans did build new hotels between 1910 and 1915. For the owner of a new hotel, the exposition guaranteed a year of total occupancy at maximum rates and enough profits to repay short-term construction loans. However, no one purposely built a sixty-year structure for only one year of business—not in San Francisco or any other city. In the long term, spurts of hotel construction like these were responses to downtown business growth. When the Panama-Pacific crowds went home, managers at the dozens of new 100-room hotels in San Francisco's Bush Street and Tenderloin neighborhoods knew they could rent rooms permanently to a combination of tourists and workers in the expanding downtown office sector. Floor plans of many downtown hotels show how their configurations could be shifted from one-room units to five-room units to match seasonal or occasional changes in the market (fig. 3.14). However, in San Francisco as in other cities, people of middle incomes who wanted

Figure 3.14

Plan of a typical floor in the Algonquin Hotel, New York City.

Accommodations could range from one room to five-room corner suites.

to live downtown were not forced to accept life around Union Square in a classic midpriced hotel. By 1900, developers offered a range of other rental housing options in both hotels and apartments.

Alternative Quarters

In addition to the classic example of a hotel purposely built as a midpriced hotel, middle-range hotel options came in at least four other modes: back halls of palace hotels, formerly grand hostelries, converted houses, and residence clubs. Apartment options at this price range, not readily available in 1880, became far more accessible both in number

and in price between 1910 and 1930. The different types of midpriced hotels showed more variation than did palace hotel life, in part because midpriced hotels served a much larger and more scattered market. In most cases, however, the midpriced hotel matched the values and norms of the middle and upper class, albeit sometimes with difficulty.

Variations of the Midpriced Hotel

If a young business person of moderate means hoped to rub shoulders with upper-class investors, his or her most logical choice of a hotel home would not have been living in a midpriced enterprise at all but rather renting a back hall room at a palace hotel. Few palace hotels could be as imperious as Boston's old Tremont House, which charged only one high rate. Prices usually varied widely. Jefferson Williamson notes that before the Civil War the grandest hotels—those advertising prices of $2 a day for board and room—offered "in profusion" 50-cent or $1 accommodations for lesser rooms.[55] As hotel owners installed indoor plumbing, prices of rooms with a private bath could be two and a half times greater than rooms in the same hotel but with a shared bath down the hall. Hotel architects relegated such rooms to areas along alley walls, in noisy corners of the building where the only light came from narrow air shafts, or where the occupants would have no view (fig. 3.15). In the 1920s, managers at the Chicago Beach Hotel on Lake Michigan charged a middle-income rate of $56 a month for a room without bath in an old wing built in the 1890s; meanwhile, lakeview suites in the newest section started at a princely rate of $700 a month.[56] Even the lower-priced rooms at a palace hotel had the advantages of service, public rooms, and general prestige. But they betrayed themselves in social engagements. "No, don't bother to come by our rooms, we'll meet you in the lobby," was the refrain of back hall hotel residents. Middle-income residents could also locate their hotel home in a palace hotel that had fallen slightly from social grace, thanks to the real estate process known as filtering. If palace hotel tourists shifted to a more fashionable hotel, the rents in the older building usually dropped into a range affordable at middle-income levels.

Small hotels at the lower end of the midprice rank hung on to their social class respectability with difficulty, and their amenities sometimes ranged precariously close to their poor relatives, the rooming houses. To qualify socially for residents of middle income, even the smallest

Figure 3.15

Plans for the ground floor and a typical upper floor of the Hotel

Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, published in 1924. Single hotel rooms

are at the back, suites at the front. Unusual room labels include

H.R . for single hotel rooms and S.P . for sleeping porches.

Most living rooms have Murphy beds.

hotel had to have a lobby and a dining room on the ground floor (fig. 3.16). For the smallest midpriced hotels, architects tucked cafés or dining rooms into the back of the building, under skylights at the bottom of light wells, or into reasonably well lighted basements. Better room furnishings, more unctuous staff, and having an elevator also helped to distinguish small midpriced hotel buildings from mere rooming houses.[57]

Figure 3.16

The dining room of San Francisco's Hotel Cecil. With a fairly low ceiling

and awkwardly placed columns, this dining room was architecturally

a step down from the dining room of the Delmonico Hotel but

still proper for middle-income patrons on a tight budget.

These smaller hotels descended from the long nineteenth-century tradition of respectable boardinghouses—single-family houses converted to commercial housing use. To attract people with polite middle-income pretensions, either the food offered or the architecture of the original house had to be quite grand. Two San Francisco houses in the lower Nob Hill area, both converted to boarding operations by the 1880s, show the edge of social propriety (fig. 3.17). Miss Mary J. Fox and Mrs. Robert McKee rented out rooms or suites of rooms in their modest houses on Post Street near Jones. They borrowed social sheen from the much larger houses a block uphill to the north, on Sutter Street. Behind Miss Fox's house loomed a new building, the Berkshire family hotel, a four-story brick building with an elevator (a luxury feature for a hotel of its size at that time). Early insurance records simply called the Berkshire a private hotel, but it was one of the city's best family hotels, the fourth largest one opened in the city. Like the small converted houses nearby, the Berkshire was managed by a woman. By 1900, because of the built-in amenities in structures like the Berkshire, only if a single-family house were very large and opulent, perhaps built by a well-known family, could the owners convert it and charge middle-income rates.[58]

Beginning in the 1880s and continuing through World War I, real estate speculators also experimented with midpriced hotels in the suburbs. In a large and proper suburban area, developers often included

Figure 3.17

Axonometric drawing of a lower Nob Hill neighborhood in San Francisco,

1885. Single-family houses are mixed with boardinghouses (shaded)

and the Berkshire, an expensive residential hotel with an elevator.

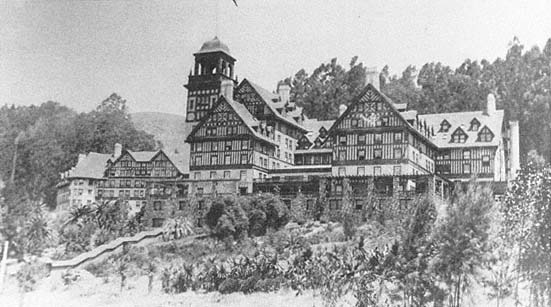

a snowy hotel—part real estate office, part residential building, part country club. In the San Francisco region, the Claremont Hotel is a quintessential example (fig. 3.18). It opened in 1915 on a wooded site with a creek and sixteen acres of gardens at a prominent overlook at the end of a major interurban transit line. Naturally, the land development company itself developed the rail line and advertised their hotel as "five minutes from Berkeley, fifteen minutes from Oakland, a half-hour from San Francisco." Two hundred rooms, half with baths, were in a 700-foot-long wooden building with 500 linear feet of porches looking out over a spectacular view of the hills, the bay, and San Francisco. Streetcars and carriages entered on one side, where there were also large stables; automobiles had a separate porte cochere and garage on the other side.[59] Below the hotel on three sides were devel-

Figure 3.18

The Claremont Hotel in Oakland, California, a classic example of a suburban resort and residential

hotel, opened in 1915. It was located at the end of an interurban line from San Francisco and was

surrounded by expensive house lots.

opments of substantial new suburban houses for the middle and upper class. The residents of these houses were expected to be frequent diners at the hotel.

Other suburban midpriced resort hotels were on beachfronts, lakesides, or hilly wooded lots along a stream. Some country clubs also had sleeping rooms, eventually used permanently. Yet after 1920, as a result of zoning restrictions and suburban market realities, further developments of such outposts of urbane commercial life were to be overwhelmed by garden apartments and rules prohibiting the mixture of uses that the Claremont Hotel meant for its surrounding neighborhood.

Residence Clubs

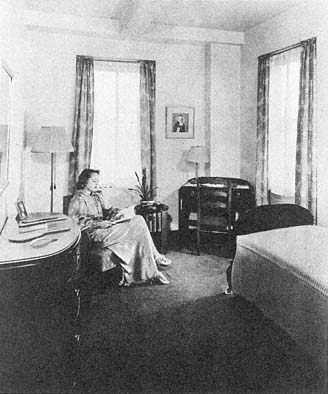

At the least expensive end of the midpriced hotel social spectrum were residence clubs offering midprice hotel amenities at a budget price. Like their plebeian cousins (the YMCA or YWCA) and also their rich uncles (exclusive private clubs), commercial residence clubs usually were tailored for single men or single women. A few clubs accommodated both single men and women by having them live on separate floors—a policy rarely used in public hotels.[60] Allerton Houses, Ltd., seems to have built the first large buildings of this type in New York just after 1900; developers in other large cities followed suit. Managers pared costs by providing very small rooms—almost exclu-

Figure 3.19

Room view from a 1939 brochure for the Barbizon Hotel,

New York City. The text emphasizes a "home away from

home" with "full-length mirror, no-draught ventilators,

three-channel radio, convenient electrical outlets."

sively single rooms—with day beds that converted to couches. Typically, about three-fourths of the rooms had a private bath.

Life in the residence clubs was like life in a YMCA but without the "C." The clubs kept staff to a minimum, especially in food service. Typically each club had its own restaurant and cafeteria or a restaurant that ran on self-service lines for breakfast and lunch and provided table service for dinner.[61] Perelman remembered a rather upscale residence club with a ground-floor coffee shop with waitresses in peach-colored uniforms who served a thrifty club breakfast costing 65 cents. "You had a choice of juice—orange or tomato," he wrote, "but not of the glass it came in, which was a heavy green goblet. The coffee, it goes without saying, was unspeakable."[62] Compared to private boardinghouses, residence clubs offered more flexible dining hours in addition to lower costs; compared to the Ys, clubs were a hefty notch higher in cost but offered more privacy and less supervision. New York's twenty-two-story Barbizon Hotel, built in 1927 and operated as a women's hotel until 1981, stood at the top of the midprice residence club scale (fig. 3.19). The women who lived there had at their disposal musical

evenings in the lobbies, a swimming pool, a gym, and a library. In hard times, a cherished tradition of the better clubs was a free daily teatime in the lobby. At one club, which tended toward a literary crowd, during teatime the lobby was said to take on the air of a book-and-author luncheon. At the Barbizon, girls on a tight budget frequently made their largest meal of the day out of the bite-size complimentary sandwiches.[63]

Apartment Hotels and Efficiency Units

Furtively cooking in one's room or continually eating in restaurants could be major irritations and expenses of hotel life. Residents who liked other aspects of downtown life often welcomed the development of affordable downtown housing units that offered private kitchens. By the 1920s, apartment hotels and efficiency units, often rented complete with furniture and dishes, were the principal downtown competition for midpriced residential hotels.[64] The typical mix of services is shown in this advertising copy from a 1920s brochure:

Exclusive Apartments—Hotel Service: The Plaisance contains 126 apartments of one to four rooms, all beautifully furnished and completely equipped. All with private baths—the four-room apartments with two baths. A large lobby, parlor, ladies parlor, and general dining room are situated on the main floor. There are shops necessary to insure comfort and convenience for the guests of the hotel. . . . Every apartment has a breakfast room and buffet kitchen completely equipped.[65]

In apartment hotels, buffet kitchens or service pantries were small kitchens with a minimum of counter space but a full-sized sink, an ice-box or refrigerator, and at least a double hot plate and a warming oven, if not a full cooking stove. Tenants in an apartment hotel could cook, take their meals in the public dining room, or (for an extra fee) have meals served in their own suite using their own silver, linen, and china if they chose. The staff of apartment hotels often took over window washing and making the beds along with periodically scouring the sink, icebox, and cupboards.[66]

Apartment hotels were often outside of downtown on parks or parkways, along major avenues and streetcar lines, adjoining new suburban apartments, or replacing former downtown mansions. In 1929, a nationwide survey revealed that apartment hotel buildings were typically large—100 units with an average of 2.7 rooms each—and most rooms

Figure 3.20

Plan of a typical efficiency apartment, published in 1924.

were rented furnished. About half of the buildings had separate maid's rooms and garage space available to tenants.[67] By the 1920s, design guides identified three distinct price ranges. Expensive examples offered full apartments with all the public rooms and services of midpriced hotels. Medium-priced examples had a lobby, desk staff, a ballroom, a billiard table or two, and a roof garden. The least expensive buildings had only switchboard service and porters for ice, groceries, garbage, and errands. These buildings more closely resembled average efficiency apartments.[68]

The minimum apartment for the middle-income household was the efficiency apartment, perfected between 1900 and 1930 (fig. 3.20). At about $25 a week (in 1920s prices) efficiency apartments were bargain versions of the apartment hotel, which started at about $50 a week (table 2, Appendix). The central innovations of efficiency apartment designs were folding beds—doors with attached, spring-loaded bed frames. These allowed tenants to turn the bed upright and pivot it into a closet or dressing room. The most common brand, the Murphy bed,

was named after a San Francisco manufacturer. Rebuilding after the 1906 fire, together with the general population and building boom on the West Coast, created such a large initial market for Murphy's new folding beds (and for a host of early imitators) that journalists reported the efficiency apartment itself had originated in California. Like so many other apartment innovations, Murphy beds had been initially marketed primarily to hotels.[69]

By 1911, the tiny kitchen areas in efficiency apartments (originally called buffet kitchens) were common enough and socially correct enough in San Francisco apartments so that local housing reformers gave them special consideration in proposed housing laws. By the 1920s, similar six-foot by eight-foot rooms were popularly called kitchenettes. They epitomized the simplifications in cooking and reliance on packaged foods that also marked smaller kitchens in new single-family houses.[70] Unskilled women working in canneries and food processing plants were doing many of the food preparation steps formerly done in individual kitchens.

Compared to tenement flats, apartment hotels and efficiency apartments were expensive. To live cheaply and comfortably in a middle-income apartment, single people either had to have quite a high income or had to relinquish their independence and team up with roommates. Group living proffered certain benefits—among them, regular company at meals and better space. Not everyone, however, wanted a roommate, and few apartment landlords wanted to rent to nontraditional household groups. Edge-of-the-city apartment complexes of the time were not a strong alternative for single people. As late as 1942, Parkchester, with its 12,000 units in the Bronx, had fewer than a dozen single people living in their own apartment, and those residents were mostly retired. The adjacent Hillside Homes project had 1,410 families but only 14 unattached people.[71]

Room for Exceptions

Anecdotes give only scattered views of the people who lived in midpriced hotels. The sociologist Day Monroe, using information from the 1920 census, left a thorough perspective of Chicago's hotel residents. Unfortunately, Monroe eliminated single people from her study, but her survey of Chicago's family groups revealed that 3.4 percent of the

families lived in rooming houses and hotels. This proportion equaled only about one in thirty families, fewer families than were living with relatives. However, Monroe's total sample had included the burgeoning immigrant populations of Chicago; few immigrants, rich or poor, lived in hotels. Thus, only when Monroe looked at particular social groups did she find hotel families comprising a more significant fraction. According to her, the three family groups with the highest proportion of hotel dwellers were those headed by professional men and women, families of executives and officials, and the families of low- to medium-salaried employees.[72] She gave the following detailed figures:

|

Eight percent of the professional households, one family in twelve, lived in hotels. The unemployed and unskilled listings in the table do not reflect the massive numbers of Chicago's single casual laborers living in hotels.

Monroe found other groups with reasonably high levels of hotel living, groups that overlapped the professional and skilled strata. Prominent among these were childless couples and young parents; almost 10 percent of Chicago's childless couples lived in hotels. The data showed young parents still figuring heavily in hotel families; many of the mothers were under twenty-five years old.[73] Monroe reported that one out of six of Chicago's single fathers with only one child under fourteen years old were living in hotel housing in 1920. However, Monroe found that single women with children were much less common in hotels; she believed this was because their income levels were so much lower.[74]

The 8 percent of Chicago's professional households that lived in hotels in 1920 were a telling minority. If a family could afford hotel life, they could afford an apartment. Virtually any of those households could also have paid for a private house—a small house on expensive

land close to downtown or a larger house in more distant suburbs. We cannot precisely reconstruct why these families chose hotels. The important point is that one out of twelve of these households did choose hotel life. For at least part of their life, these households did not fit the dominant pattern for the middle-income American family, that is, living in a house or an apartment of their own. These families had made an eccentric choice of family residence; however, the one professional family in twelve living in hotels were not necessarily eccentric families. Their reasons for being downtown—waiting for a house to be built, holding nearby jobs, staying only for a year or two, caring for an elderly parent who needed some looking after during the day—were reasonable and practical. Suburban life did not work for them, at least during one part of their life cycle, and hotel life did work.

Hotel life left room for such exceptions without eliminating any other options. For a reasonable number of family people in the comfortable salaried strata, the commercialized option of cooperative housekeeping was viable and desirable. For a more complete picture of the role that midpriced hotels were playing in the metropolitan housing stock, we can only wish that we knew how many of Chicago's single professionals and single elderly were living in hotel housing in 1920.

Unfortunately, the people who gradually codified the single-family house ideal rarely allowed for exceptions or minority opinions. As early as the 1850s, one of Nathaniel Hawthorne's characters observed urban life from a hotel and objected to the "stifled element of cities," the "entangled life" of so many people together. People were "so much alike in their nature, that they grow intolerable unless varied by their circumstances." The alternatives Hawthorne's character had in mind were the individualized little farmhouses like those he had just left behind in rural New England.[75] This example is simply one among thousands of such well-meaning statements from the century of building, writing, and living that helped to confirm the monolithic ideals of the single-family American house. The rural and small town social experiences and values of opinion leaders like Hawthorne became sedimented in their actions and writing—particularly in their verbal support for the single-family home and abhorrence of any variation from that single ideal. Not all nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century writers excluded alternatives or exceptions in housing, but most did. In their values, neither Hawthorne nor his characters left room for those future people—

perhaps the one family in twelve in 1920—who could not or who did not want to fit into the norm of a private house or a private apartment with a private kitchen and a private dining room and a life untouched by neighbors. The repercussions of this kind of exclusion in housing would not become clear until almost a century after Hawthorne died.

If the pleasant hotel life of those with professional salaries was to some people a stifled and entangled life, then the life of the next cheaper type of hotel, the rooming house, was surely beyond the pale. Indeed, the downtown life in rooming houses that so often were only a block or two away from midpriced hotel zones frequently crossed the line from the realm of the middle and upper class to a realm of a very separate class.