Portland, Oregon:

A Positive Catalytic Reaction Requires an Understanding of the Context

A single solution or formula will not work in all situations. There is no best form or best goal in urban design; forms and goals depend on specific situations. Milwaukee is different from Georgetown, which is different from Kalamazoo. In Phoenix, for example, the existing street grid is understood as a neutral framework that allows aggregation and subdivision (see Figure 90). But in Portland, the street grid itself is a valued element of downtown.

The importance of understanding a place is demonstrated in the efforts to revitalize the traditional retail core of Portland, centered near the

67.

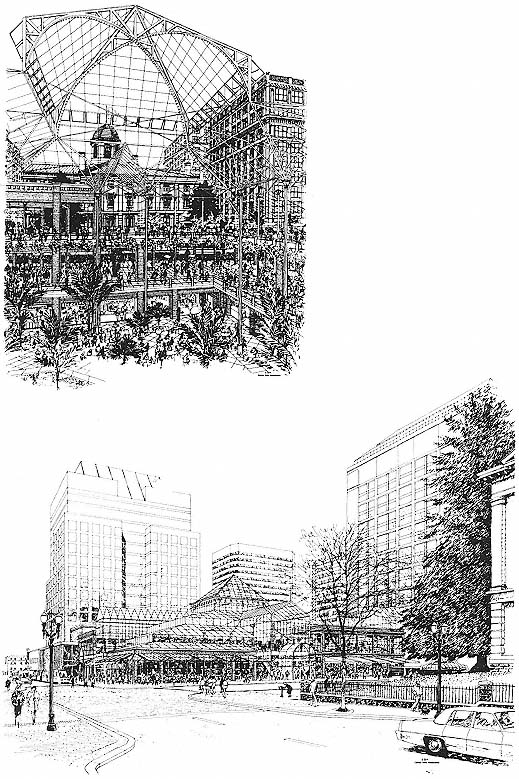

Cadillac-Fairview proposal by Zimmer Gunsul Frasca Partnership, 1979–1981.

68.

The fabric of Portland, with its distinctive street grid and parks,

including the linear park called South Park Blocks (lower left).

Portland's role as a regional production and distribution center

began in the nineteenth century, with timber as a major commodity.

This role continues but has been diversified. In response to

urban decay in the 1950s and 1960s, the city has engaged in a

number of successful regenerative projects; for the most part,

the valued heritage, the inherited urban fabric, has been

respected; often it has been reinforced.

Pioneer Courthouse at Fifth and Morrison streets. Cadillac-Fairview developers proposed a multi-use scheme covering four blocks near this important intersection. The blocks would be linked by skybridges. But even though the Cadillac-Fairview scheme included up-to-date concepts and images for a multi-use urban center and would have been acceptable—even praised—in many cities, it was perceived to be undesirable for Portland. In the course of extensive public discussion, several shortcomings were identified, many of which had to do with the local context, with misunderstanding Portland:

First, the scheme seemed too much like "a suburban shopping mall turned inwards. It ignored streets, the neighborhood, the historic buildings, and the people who care about the fabric of our city life."[8] The

metaphor of fabric is popular for talking about the ingredients that give an urban center a sense of cohesiveness. Portland's fabric includes a distinctive, delicate grid of streets: the blocks are unusually small (200 by 200 feet) and the streets unusually narrow (60 to 80 feet). As a consequence of this fabric, pedestrians seem to belong downtown; the city is scaled for people on foot. Streets are not gulfs to be negotiated. Buildings, even when tall, do not loom. Although functionalist theory would propose linking these small blocks into superblocks and eliminating some "obstructing" streets and widening others as major arterials, Portland's fabric is as it should be, with intensive development of the small blocks and enrichment of the pedestrian realm on the periphery of those blocks. Although the scale of many American street grids works against what is called street life, in Portland the grid was made for it. There, anything that reduces pedestrian use of and access to streets is suspect. The complaint that the Cadillac-Fairview scheme was turned inward, like a suburban shopping mall, was a response to this concern.

Another ingredient of Portland's fabric is its collection of highly prized open spaces. These are of two kinds: block-sized parks that provide relief from the intensive development of the grid and a linear park stretching along the west edge of downtown.

Second, the Cadillac-Fairview proposal to violate the grid pattern with skybridges (some of them wide enough to contain shops) was offensive to some people. Not only would these destroy the sense of the city's fabric, but they would also block sunlight on the streets (infrequent enough in Portland to be valued) and the views down streets (to the hills, possibly even to the city's totem, Mt. Hood). The skybridges would also mean a loss of pedestrian traffic on the sidewalks.

Third, although Portland's older buildings in themselves are not remarkable, that there are so many of them left is . In the last decade or two the merit of the architectural heritage has been recognized, first in the form of historic district designations on the edge of downtown, then in the renovation of individual structures throughout the city center. For some critics, the Cadillac-Fairview proposal was incompatible with many older buildings, particularly the historic Pioneer Courthouse, which would be dwarfed by the new complex. There was concern, too, about the adverse impact of such a large project on the adjacent Yamhill Historic District. Even though the design and planning controls of the district were probably strong enough to minimize adverse effects, concerns were voiced that a large project, one that violated the existing scale of the city, might also violate other valued elements of the downtown.

Fourth, the scale of the complex was also of concern. The idea of a single "imperial" (and foreign—Canadian) corporation turning four city blocks into a self-contained complex seemed more appropriate to Los Angeles (one critic called it a "Star Wars" concept) than to Portland. Portland prides itself on its up-to-date achievements, but its values are inclined to be more humanistic than systemic. A project of this scale would focus too much attention on itself, would turn its back on the smaller retailers in the area, and would threaten the charm of downtown.

Fifth, the politics and economics of the project caused some complaints. Housing for low-income residents would be lost and not replaced. Municipal funds would be used to subsidize a private enterprise.

Partly because of negative public reaction to the concept and design, partly because of the economic climate at the time, and partly because the developer and the Portland Development Commission could not agree on terms, the Cadillac-Fairview project did not proceed. As a result of the discussion, however, the value of a combined retail and mixed-use project on this site was realized, and other developers were invited to submit proposals.

Ultimately, the Rouse Company was chosen to build a project that is more responsive to downtown Portland—that is to say, one that is a better urban catalyst because it recognizes and accommodates the local ingredients. It acknowledges the elements that make downtown Portland distinctive. Instead of plunking a multi-block complex across the street from historic Pioneer Courthouse, the development, named Pioneer Place, will move the largest elements back one block and thus make the courthouse the center of an implied three-block-long downtown public place. Its edges will be defined by the facades of the surrounding office

69.

Morrison Street scheme, Portland, ELS / Elbasani and Logan, architects, 1983.

70.

Morrison Street scheme, Portland.

buildings and department stores. The new, extended, public realm will include the Pioneer Courthouse at its center, the recently completed Pioneer Square (the city's first real piazza) at the west end, and to the east a new, highly accessible, retail pavilion that is perceived as complementing the traditional retail pattern of downtown as well as the courthouse. Thus the fabric of downtown open space will be reinforced and enlarged to include a new focal feature, the pavilion. The sense of the valued Portland grid is retained by treating each piece of the development as a separate element. Even though there are skybridges, they are as narrow as possible and do not contain shops.