An Overview of Woodstove Safety

Americans rediscovered the woodstove in the 1970s, almost 250 years after Benjamin Franklin designed the first model intended primarily for heating rather than cooking. Sales of woodstoves tripled between 1974 and 1978. With increased popularity came improvements in technology. Franklin's design was altered first by the addition of doors—the Franklin stove was simply a firebox with an open front—and more recently by airtight construction that makes stoves burn hotter and more efficiently.

Woodstove-related fires also became common in the 1970s. Woodstoves were mentioned frequently in fire incident data analyzed by the Center for Fire Research at the National Bureau of Standards. Whether these hazards should he addressed through safety standards is disputed. It is widely agreed, however, that woodstoves are potentially dangerous. "Making wood heat an effective alternative to conventional heating requires the ultimate in careful planning," warns a popular consumer magazine.[2] In the absence of proper precautions, woodstoves pose four general hazards: creosote fires, ignition of nearby combustibles by radiant heat, escaping sparks or fire, and surface burns.

The Creosote Problem

Creosote fires account for approximately 60 percent of woodstove-related fires. Creosote is formed when the moisture expelled from burning wood combines with unburnt combustible gases in the flue. A tarry substance builds up on the flue lining, eventually becoming brittle and highly flammable. If the chimney is not cleaned in time, high temperatures will start a fire that can spread to the surrounding structure through radiant heat or, if the fire is hot enough, by burning through the chimney.

The process of burning wood inevitably produces creosote. The amount depends on the type of wood, its moisture content, and, most important, the temperature of the fire. Greener wood creates more creosote. So do low burning temperatures, such as those obtained when the stove damper is adjusted for overnight burning. Product design also affects creosote production. New high-efficiency stoves burn hotter and create less creosote than most traditional models. Catalytic combustors, an even newer technology, reduce creosote production through a complex chemical interaction between wood smoke and noble metals such as platinum that enables the smoke to release more heat before going up the chimney.

Nearby Combustibles and Other Hazards

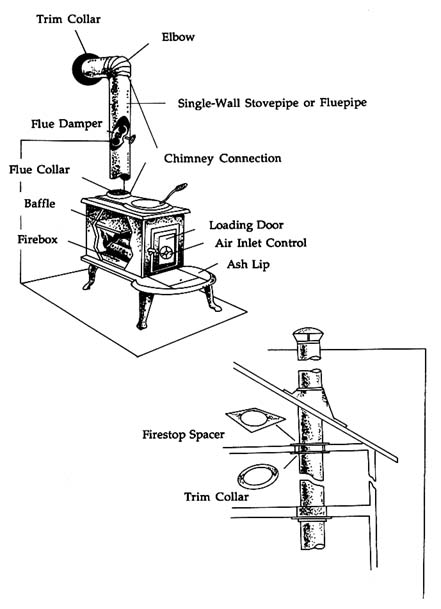

Woodstoves radiate heat that is deceptive in its capacity for igniting nearby walls or furniture. As a rule of thumb, stoves should be installed at least thirty-six inches from the wall and surrounding furniture. This varies both by stove and by building material, but installing a stove even a foot too close to a wall can eventually result in a fire. There is a similar problem with chimney connectors and other piping, which require

about an eighteen-inch clearance from the wall and ceiling but are often installed closer, particularly when passing through a wall or ceiling (see figure 2). Approximately 20 percent of woodstove-related fires are thought to be caused by insufficient clearance to combustibles. Some experts consider the connection to the chimney—rather than the distance from the wall—to be the most dangerous aspect of woodstove installation.

The third hazard, least significant in occurrence, is that fire will escape from the stove. This includes fires caused when (1) sparks escape from the air inlets, (2) coals or flames escape through the stove door (often because it is open), and (3) the fire actually burns through the firebox.

The final hazard associated with woodstoves is the most common, the least severe, and is almost impossible to control through regulation. It is surface burns caused by contact with a hot stove.

Are Woodstoves a Serious Problem?

Woodstoves appear to pose a sizable safety problem. They are second only to careless smoking as the leading cause of residential fires. The CPSC estimates that solid-fuel heating equipment was involved in 140,000 fires in 1985, causing approximately 280 deaths and over $300 million in property damage.[3] There are several reasons to discount the significance of these numbers, however. First, they stem from dubious extrapolation techniques.[4] The CPSC's sample is limited and nonrandom. The data do not distinguish between woodstoves and fireplace inserts. They are both lumped together under "solid-fuel appliances," leaving it unclear how much of the problem is actually attributable to woodstoves. Moreover, reports compiled by local fire departments are usually sketchy and sometimes inaccurate in assessing causes.[5]

Second, these national estimates conceal the fact that most woodstove-related fires are minor. According to the National Bureau of Standards, "of the 11,534 residential solid fuel related fire incidents reported in the [eleven-state] data base … the loss was under $1,000 in seventy-two percent of the fires."[6] Finally, and most important, it is not clear whether any of these hazards, whatever their frequency, can be reduced by product standards. There is a report in the CPSC files, for example, of an injury caused when an adult tried to retrieve an aerosol can from his woodstove. Obviously, no product standard could prevent

Figure 2. Woodstove and Wall Pass-through System

this kind of injury. This is not necessarily true of all, or even most, fires commonly attributed to the consumer. "Injuries," as one independent consultant put it, "are often caused by an unfortunate combination of design, installation, and use." The number of fires directly attributable to the product itself is probably very small.[7]

Even with all these uncertainties, both a public and a private organization chose to write standards for woodstoves. UL officially proposed a draft standard for woodstove safety in January 1978—seven months after the CPSC received a petition requesting that the government regulate woodstoves. But forestalling government regulation was not, as it might appear to have been, UL's motive. The UL standard (in "unpublished form," as explained later) actually predates the petition to the CPSC by several decades. Moreover, there is minimal overlap between the CPSC's standard and the UL standard. The former addresses only labeling; the latter aims to be comprehensive and includes performance tests and design requirements as well as labeling requirements.