Chapter Five

California Wine and World War II

The boom in wine consumption expected after Repeal in 1933 did not arrive until 1942. The result of a managed wartime economy that took whiskey off the shelves and put money in consumers' pockets, the boom permanently changed the structure of wine production and distribution in the United States by breaking the strength of regional bottlers and by creating an economic environment conducive to the introduction of national brands and at-winery bottling. As is characteristic of most boom periods, the five years beginning in 1942 and ending in 1946 saw a massive influx of capital, with resulting fraud, lawsuits, and bankruptcies. Sales and purchases of wineries accounted for at least 40 percent of the production capacity in California. Grape prices tripled, and over 57,000 acres of new vineyards were planted, an increase of over 10 percent from the 1941 acreage.

These structural and organizational changes reached across the entire industry, affecting wineries and growers in Southern California, the Central Valley, the North Coast, and the Napa Valley. The crash of the wine market in 1947, as the industry readjusted to competition, a surplus of output, and the removal of price controls, was felt as deeply in St. Helena as it was in Fresno or San Francisco. Yet, even with the crash and its resulting business failures, the California wine industry emerged from the war years fundamentally different and ultimately stronger.

Prior to World War II, the California industry was, broadly speaking, a collection of commodity processors who produced a bulk, unbranded product and shipped it via rail tank car to independent regional bottlers across the United States. Estimates vary, but probably 80 percent of Cal-

ifornia wine was shipped out of state in bulk, and much of the remaining 20 percent was bottled in California under contract with out-of-state distributors under their labels.[1] Although such large wineries as Petri, Roma, and Italian Swiss Colony shipped bulk wine to every "wet" state, that was no guarantee that the company brand was known to consumers across the nation. In some instances, wineries owned their own out-of-state bottling facilities and simply shipped bulk wine for convenience. In other cases, independent bottlers operated under "franchises," bottling a California producer's wine and labeling the product with both their own and the producer's names.[2] But the independent bottler usually had its own set of brands and its own distribution sales force in the local market. While such regional bottlers often created on-going relationships with specific producers whose wines and credit terms they liked, the bottlers always knew that the wine they were purchasing was a commodity, one generally in surplus.

Wine was in surplus and often of questionable quality because grapes were abundant and often of the wrong variety. Between 1920 and 1923, owners planted over 300,000 acres of grapes, primarily in the Central Valley, doubling the pre-Prohibition acreage. Of this new grape acreage, over half produced raisin varieties, and fewer than 20 percent of the vines planted were wine varieties.[3] Indeed, by 1940, one raisin variety, Thompson Seedless, covered more acreage than all of the wine grapes in California.[4]

The speculative planting of thicker-skinned raisin and table grape varieties during Prohibition produced a chronic oversupply following Repeal, especially in the wake of four successive large crops in 1937, 1938, 1939, and 1940. For many growers, the fermenter became the last resort for unwanted raisin and table grapes. Ripe raisin grapes such as Thompson and Muscat could be crushed, fermented, and distilled, serving as a source of fortifying brandy for dessert wines. Although these raisin varieties produced poor wines, few growers were concerned about resulting wine quality. Their general attitude was succinctly stated by the manager of the Growers' Grape Products Association: "Any grape may be utilized for wine or brandy."[5] Thus in 1940, although less than 28 percent of California's grape crop consisted of wine grapes, over 54 percent was crushed for wine.[6] The immediate results were easily predicted: low wine prices, poor wine quality, and a buyer's market for out-of-state bottlers. The longer-term outlook was economic disaster.

Had it not been for changes brought about by the war, the California wine industry probably would have faced a decade of decline and con-

solidation. Instead, by 1942, grape prices had doubled, and wine was in short supply.[7] This dramatic reversal resulted from changes in both supply and demand. The raisin surplus was "solved" in 1942 for the duration of the war when the federal government requisitioned the entire crop for use in the war effort.[8] Compact, high-energy, and relatively non-perishable, raisins were an ideal food for inclusion in K rations. Through the 1945 harvest, the federal government restricted the use of raisin varieties to raisin production.

The effect was immediately evident in the 1942 crush figures: in 1941, California had produced a total of 110 million gallons of wine, but the amount fell to just over 62 million in 1942, the low point for the decade. The loss of raisins was especially felt in dessert wine production, which accounted for roughly 80 percent of all wine sales: production dropped from a 1941 high of 72 million gallons to 37 million gallons in 1942.[9] The 62 million gallons of wine produced in 1942 amounted to slightly less than two-thirds of the wine sold the previous year. With the glut of raisins removed, the wine industry moved abruptly from a state of surplus to one of scarcity in less than a year.

The one-third reduction in supply was combined with an increased consumer demand for wine, since it was the only readily available form of alcohol. Following the outbreak of war, the federal government immediately requisitioned all distilling operations, demanding around-the-clock production of high-proof alcohol for the war effort. By October 1942, whiskey distillation had ended, creating immediate shortages on retail shelves.[10] Although there was ample whiskey in barrels, the distillers chose to hoard their supplies, as they were unsure when they would be allowed to produce whiskey again. Beer, a product of cereal crops used for the war effort, was available but "trade-rationed." Only wine, a beverage produced from a fruit not vital to the war effort, was freely obtainable to a home front whose purchasing power had almost doubled as a result of the war economy. Per capita annual consumption of wine rose from .68 gallons in 1941 to .84 in 1942, reaching a peak of 1.0 gallon in 1946.[11] In all probability, the rise would have been faster and greater had more wine been available to slake America's thirst.

In a free market, increased demand coupled with decreased supply raises prices. But during the war years, the United States was not a free market, and price increases occurred only in the raw product, grapes, and not in wine itself. This was because the government placed price controls on manufactured goods, but not on agricultural raw products. In order to prevent inflation, which had been experienced in World

War I and had already begun to take place in 1941, Congress passed the Emergency Price Control Act in early 1942. It created the Office of Price Administration (OPA), which placed an immediate price freeze on most manufactured goods.[12] However, the act also prohibited price controls on raw agricultural commodities unless the price was at least 110 percent of "parity," a concept more applicable to soybeans, tobacco, and peanuts than to wine grapes. Establishing a parity price was both time-consuming and political. The Department of Agriculture chose not to calculate a parity price for grapes, and the OPA thus never did put price controls on wine grapes. The immediate upshot was that wine prices were more or less frozen for the duration, while grape prices were left free to rise, increasing from an average of $16.50 a ton in 1940 to $100 a ton in 1944.[13]

The predictable effect of government regulation was, therefore, a reduction in wineries' profit margins. This in turn caused an abrupt curtailment of bulk wine shipments from California wineries to out-of-state bottlers. The longer-term consequences were a movement toward bottling at wineries and an invasion of the California industry by out-of-state bottlers and distillers in 1942 and 1943. These repercussions of the wartime disruption of normal supply and demand all followed in a logical, if curious, cascade.

The first effect of price controls was an abrupt decline in the profit on bulk wine, which had accounted for most of California's sales. After initially setting bulk dessert wine prices at 32 cents a gallon, the OPA raised the ceiling to 39 cents, and 21 1/2 cents for "current" table wine, in October.[14] A ton of grapes produces about 170 gallons of new wine, so the ceiling price on table wine in 1942 corresponded to roughly $36.50 a ton, while Central Valley nonvarietal black grapes were selling at slightly over $32 a ton.[15] Assuming, as the federal government did, a cost of 1.7 cents a gallon for base production costs, another $2.90 a ton was incurred for processing, bringing a typical raw product cost of almost $35 a ton by October 1942. Although the OPA continued to raise price ceilings for bulk and bottled wine throughout the war as grape prices increased, the difference between raw material prices and bulk wine ceilings allowed for little, if any, profit.

However, the OPA did permit a significantly higher price for bottled wine. The 1943 price ceilings limited "current" bulk table wine sales to 28 cents a gallon, but allowed the same wine to be bottled and sold at $3.74 a case, roughly $1.55 a gallon.[16] Although wineries incurred the additional expense of packaging, bottled wine sales were thus significantly

more profitable than sales of bulk wine. Wines and Vines commented, in unusually blunt language, that it was "much better to sell quality wine in cases . . . at prices which may start at around $1.50 a gallon . . . than to sell . . . at tank car prices which provide little or no profit."[17]

The sale of bottled wine was even more profitable for those wineries marketing higher-priced varietal wines, since they could legally sell at prices considerably above the regular ceiling price. Wineries that had only bottled small or special lots, dusted off old labels and diverted more of their production into higher-priced brands. Consequently, price ceilings "had the effect of practically eliminating all the lower-priced brands."[18] This change in turn pushed grape prices higher, since, as Wines and Vines commented, "distributors and bottlers" who owned "high priced brands . . . [could] afford to pay more for their grapes than . . . the average winery."[19] The price differential between bulk and bottled wine forced many of California's bulk producers to become bottlers and to develop their own brands. It also created opportunities for outsiders to enter the California industry.

Not surprisingly, the first group to enter the California industry in force were the distillers. After the outbreak of war, the distillers worked continuously to produce alcohol for the war effort and were financially secure, but were left with little or no product for their national sales forces to sell. By becoming wine producers, distillers secured a new product that could be sold in place of whiskey for the war's duration. In 1942, the large distillers entered the California industry, and within a year, four firms, National Distillers, Schenley, Seagram and Sons, and Hiram Walker controlled about 23 percent of California's wine production capacity.[20]

Schenley and National Distillers were the most aggressive in acquiring California wineries. National Distillers had purchased Shewan Jones, a moderately large winery in the Sacramento Delta, in 1939. But National shocked the California industry at the end of 1942 when it bought the two Italian Swiss Colony wineries in Asti and Clovis, effectively increasing National Distillers' production capacity sevenfold.[21] Schenley expanded even more quickly. In January 1941, Schenley bought the Cresta Blanca winery in Livermore, a small, old, higher-quality producer, with a historically higher price ceiling than most wineries. Schenley increased Cresta Blanca's production by purchasing the Colonial Grape Products Winery in Elk Grove in September 1942 and Greystone Cellars in St. Helena from Central Winery in November 1942, operating them all under the name of Cresta Blanca and dramatically expanding the production of the profitable high-priced "Cresta Blanca" wine.[22]

But the transaction that really shook the California industry was the sale of California's largest winery, Roma Wine Company, in November of 1942 to National Distillers.[23] Together, Schenley and National Distillers controlled almost 20 percent of the California wine production at the close of 1942.

The distillers' entrance into the California wine industry was bemoaned by some, feared by many, and ultimately became the subject of a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing.[24] There were charges that the big firms were forcing "tie-in sales," the practice of requiring retailers to purchase five, ten, or sometimes twenty cases of wine in order to buy one case of whiskey. Never proved, tie-in sales undoubtedly occurred and were effective in getting California wine on retailers' shelves. In turn, most retailers engaged in their own subtle form of tie-in sales with customers, encouraging wine purchases before "finding" a bottle of whiskey in the back room for a loyal customer. Such practices flourished in a wartime economy of scarcity and helped introduce California wine to a national audience.

More important, the distillers brought to the wine industry a national system of merchandising and "an influx of new, much desired capital."[25] Schenley nationally advertised both Roma and Cresta Blanca on radio and in print, and National Distillers pursued a similar policy with Italian Swiss Colony. For the first time, because of the distillers' money and sales sophistication, brands of California wine were effectively promoted on a national basis. On the whole, most California wineries adopted a wait-and-see attitude toward the distillers, appreciating their help in building a national market for California wine, but wary of their immense economic strength and political clout.

For the distillers, purchasing a California winery was a matter of seizing an opportunity created by wartime conditions; for out-of-state bottlers, direct involvement in California was a matter of economic survival. The out-of-state bottlers depended upon California wineries for their supply. As long as wine remained abundant, which it had been since Repeal, bottlers had not really needed to assure themselves of a source of supply by becoming actual producers. In some ways, the shipment of bulk wine had worked to the benefit of both groups during the 1930s. The arrangement had let bottlers concentrate scarce capital on creating a local sales and delivery force, acquiring bottling equipment, and building an inventory of bottled goods, while it let California producers focus their funds and energy on production. The war economy threatened the old relationship. Producers could survive without the bottlers, especially under wartime scarcity, but the bottlers could not survive

without a secure source of supply. As Wines and Vines put it, the problem was "so serious as actually to be a fight for existence."[26]

For the first year of the war, bottlers had attempted to ride out the wine shortage in the hope that it represented a temporary dislocation rather than a sea change in business. Many bottlers initially circumvented the price ceilings on bulk wine by receiving bulk shipments, bottling the wine for the California wineries under contract, and then purchasing the bottled wine from the California producer at close to the higher price ceiling. Such fiction allowed the bottler to pay a higher amount for bulk wine than if the bottler had bought the wine in bulk and bottled it for his own account. Another means used to evade price ceilings was for bottlers to buy their own grapes and to pay wineries to process the grapes. Both methods were effectively ended in early 1943, when the OPA ruled that contract bottling, crushing, and fermentation were essentially services that came under price control.[27] Such price control ended the possibility of producers and bottlers sharing the higher margin allowed on bottled goods, and in most cases it effectively stopped custom crushing operations on a large scale, since the producer could almost always make a higher profit by fermenting and bottling for his own account, rather than for an out-of-state bottler.[28]

The final blow came in the form of an order from the War Production Board to the Office of Defense Transportation on January 5, 1943, that converted the remaining seven hundred tank cars used for wine shipment to "the transportation of essential wartime liquids."[29] This meant that future movement of bulk wine would be in barrels, adding cost and inefficiency to the out-of-state bottlers' operations, even if enough barrels were available. Wines and Vines predicted that "once the flow of bulk wine to the East is cut down, some eastern bottling firms will have to shut down," resulting in the sale and movement west of bottling equipment.[30] The handwriting on the wall spelled out "Bottled at the Winery" in rather large letters. As one producer wrote, "It is the cold-blooded truth, and the change is here now."[31]

If 1942 had been the year of the distiller, 1943 became the year of the out-of-state bottler. Bottlers flocked to California to buy wineries and to secure a source of supply for their wholesale operations on the East Coast and in the Midwest. Leading the charge were the larger regional bottlers. Early in the year Renault, an importer and bottler, concluded that "continuation of their national business would be possible only if they acquired property in California." They purchased several wineries, the largest being the St. George Winery in Fresno, with a capacity of

over one million gallons.[32] Renault's acquisitions also included Lombardi Wines in Los Angeles and a San Francisco bottler, the Montebello Wine Company, which operated the Fountain Winery in St. Helena. In the spring of 1943, the Gibson Wine Company, a major regional bottler in Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana, bought the two-million-gallon Acampo Winery near Lodi. Taking advantage of the seller's market, the stockholders of Acampo, led by Cesare Mondavi, had decided to "offer the property to the highest bidder." As Wines and Vines noted, the purchase assured Gibson of "a steady supply of well-made and aged dessert and table wines."[33] Other large-to-medium-sized wineries changed hands prior to harvest: the Eastern Wine Corporation of New York purchased the Burbank Winery in Burbank, and Brookside Distilling of Pennsylvania bought the Alta Winery in Dinuba. Each winery had just under two million gallons of storage, or the equivalent of slightly less than 1 percent of California storage capacity.[34]

The buying frenzy slowed at harvest, as wineries concentrated on processing the vintage, but winery sales picked up again in 1944. In some instances, groups of bottlers banded together to purchase a winery, such as three New Jersey bottlers who purchased the Garden Winery and Distillery in Fowler.[35] New owners and their locations read like a directory of bottlers: Sunwest Wines of Madison; Ignatius Russo of Cleveland; Edward Bragno and Company of Chicago; Midwest Distributing of Milwaukee; R. C. Williams of New York City; Garret and Company of New York City, and John Drumba of New York City.[36] By summer of 1944, new owners held at least 40 percent of the productive capacity of California wineries.

It was not just wineries that changed hands. Sales of vineyards, or land suitable for vineyards, boomed as well. For many wine producers, buying a vineyard was a way both to secure a supply of wine grapes and to lock in raw product prices.[37] With demand for wine high, and raisins off of the market, grapes prices soared up to $100 a ton by the 1944 harvest.[38] Such price inflation dramatically improved vineyard profitability and led in turn to increased plantings from 1944 through 1946. The high point was 1945, with owners planting 22,000 new acres, but in the three-year period, they added just under 50,000 acres of new vineyards.[39]

In 1941, such an expansion would have been considered madness, but by late 1943, perhaps buoyed by the wartime economy, industry leaders predicted a postwar market for 250 to 500 million gallons of wine, almost a fivefold increase over the record 1941 crush. Arguing that "there seems

to be little doubt of finding a market to absorb all the wine we can make," Wines and Vines urged growers to plant only wine varieties, so as to ensure high-quality wines after the war.[40] Despite this caveat, and the 1944 publication of Amerine and Winkler's Composition and Quality of Wines and Must of California , which argued for increased plantings of better-adapted wine grape varieties, not all growers followed such advice. Winkler indicated that of the 35,000 acres planted in 1944 and 1945, only about 19,000 acres, or 55 percent, were in wine grapes. Of these "wine grapes," well over half were varieties that gave heavy yield but low quality, such as Burger, Carignane, Palomino, and Mission.[41] The reason was obvious. Few wineries paid much of a premium for higher-quality grapes, and the vineyard owner, who finally saw his opportunity after almost a decade of low prices, was interested in tonnage, not quality.

Throughout 1944 and 1945, the new owners of California wineries and vineyards continued to invest in new equipment and in brand development and advertising. They bought bottling equipment from defunct regional bottlers and transferred it to California, resulting in increased capacity for at-winery bottling. Roma doubled its bottling capacity, from 10,000 cases to 20,000 cases a day, between 1941 and 1945. Other wineries followed suit. Petri increased output from 4,500 cases to 17,500 cases, the Madera Winery went from 1,500 to 10,000 cases, and the Italian Swiss Colony grew to 3,000 cases a day. Wineries that had bottled by hand mechanized. Wines and Vines estimated that by 1945, roughly 60 percent of California wine production could be bottled in California.[42] The growth in bottled wine production was matched by an increase in brand and generic advertising. Harry Caddow judged that in 1945, almost $10 million was spent on brand advertising. A year later, brand and generic advertising was estimated to be close to $15 million, up from barely $500,000 in 1938.[43] By 1945, the California winemakers had irreversibly changed from a group of mainly bulk producers of a commodity in oversupply to producers and marketers of branded commodities in short supply.

The accelerated rate of change in the California wine industry must have been dizzying. Writing in June 1944, Elmer Salmina of Larkmead in St. Helena claimed that "practically everyone with a bonded winery has been approached by buyers" but cautioned that many were "speculators who are gambling in the wine business." He confessed to being "more and more confused when I hear or read of sales of vineyards and wineries at unheard of prices." Unwilling to predict the future, Salmina cautioned that although "this may just be the beginning . . . [but] when-

ever there is a beginning there is an end."[44] Carl Bundschu echoed Salmina later that year when he warned growers that "the present price of grapes will not last," and that the resulting inflation would eventually "bring ruin to some vintners when business drops to normal." The problem, according to Bundschu, was that high grape prices invariably forced up wine prices, and "no wineman wants to be caught with a large stock of high-priced wine when the crash comes, and it is bound to come."[45] Such predictions fell on deaf ears. Clearly, the prosperity was war-induced, but for those with grapes or wine to sell, it was nonetheless real. The question no one seemed willing to pose was how long the prosperity would last following the war's end.

Throughout 1944, most California wines sold at their maximum ceiling prices, and "mixed black" grapes from the Central Valley reached a high point of $100 a ton during the 1944 harvest. One result was a decline in wine quality, since wineries were forced to turn over inventory quickly if they were to make any profit under price controls, thus leading to the bottling and marketing of young wine as quickly as possible.[46] Still, demand remained high throughout the first months of 1945, and even as the end of the war drew nearer, most producers remained confident that the boom would continue. But as the industry entered the traditionally slow summer months, demand slackened for the first time, exposing producers to the risk predicted by Bundschu.

The reaction was predictable: general price cutting and instances of panic selling. By August, wine sold at below price ceilings, and by fall, prices had fallen on average by 25 percent.[47] Fearing that prices would drop in following months, wholesalers became reluctant to buy wine in any quantity and demanded that producers guarantee proportional credit on purchases should prices continue to decline. The softness of the wine market was exacerbated by the government's decision to purchase only a portion of the raisin crop. Availability of raisin grapes meant the industry could increase its production of dessert wines, which had been curtailed, but also meant an increase in total output, with a potential further decrease in bulk wine prices. As a result, grape prices fell by almost 50 percent, to an average of $57 a ton, and a record 116 million gallons of wine were produced. By late fall 1945, following the crush, dessert wine sold at about 80 cents a gallon, down from $1.10 the previous spring. Prospects seemed strong for a further decline.[48]

The last half of 1945 had demonstrated just how precarious the wine market could be, but pessimists were proven wrong in 1946, when the industry entered another boom period. One result was that for the first

time in history, annual U.S. wine consumption passed one gallon per capita. More to the point, the wine sold fetched high prices. Partially as a result of the slackening of wartime price controls, as well as of the scarcity of other forms of alcohol because of the government policy of encouraging grain shipments to war-ravaged Europe, demand and price both increased steadily throughout 1946. Retailers and wholesalers who had purposely kept low inventories while prices were falling in 1945 now rushed to buy as prices rose.

During 1946, almost each month set a new record for wine taken out of winery storage. By February, dessert wine prices had climbed to over $1.00 a gallon; by April, they had reached $1.40.[49] Declaring that "supply of bulk wines for sale is practically non-existent," the editor of Wines and Vines commented that price increases were "by five- and ten-cent jumps."[50] Even in the usually slow summer selling season, sales and prices continued to rise, with dessert wine prices escalating to an unheard-of $1.90 a gallon.[51] Wine removals for the first half of 1946 totaled 61 million gallons, 50 percent ahead of comparable sales for 1945, at a time when sales had never topped 100 million gallons for a full year.[52] Herman Wente, the president of the Wine Institute, articulated the prevalent sense of optimism when he declared that "the wine train is set for a long, high-speed run. The track ahead is clear and has no visible ending."[53]Wines and Vines shared his view, arguing that there was "little reason to expect a price drop."[54] The industry foresaw continued growth and acted on that belief.

As the California industry entered the summer of 1946, it braced itself for a record crush by increasing fermenting and storage capacity by 45 million gallons.[55] Although availability of raisin grapes assured a large harvest, prices of grapes increased as harvest drew near. Led by distillers, most notably National Distillers' Italian Swiss Colony and Schenley's Cresta Blanca and Roma, wineries competed for uncontracted tonnage, driving prices to between $85 and $90 a ton for Central Valley mixed black grapes.[56] Increased grape tonnage, high grape prices, and expanded fermentation capacity led to a record 1.6 million tons of grapes being crushed in 1946, an increase of almost 50 percent above the previous record the year before, and double the amount crushed two years earlier in 1944.

California wineries ended 1946 with a large and very high-priced inventory. This was not a problem as long as demand and prices increased. Some wineries, believing that wine was still underpriced relative to other forms of alcohol, raised prices, arguing that wine prices should increase

with general inflation. Others, remembering the selling panic in the summer of 1945, feared that consumption was likely to drop with any increase in prices and cautioned that "once prices are forced to move down, there is no telling where they will stop."[57] This time the pessimists were right.

Slow sales in January and February, a response to high-priced wine, the new availability of blended whiskeys, and overstocked retailers' store-rooms, initiated a round of price cutting by wineries that feared being "stuck . . . with high priced inventories."[58] Industry spokesmen counseled gradual price reductions and argued that the post-holiday decline in sales was a natural "breathing spell" for retailers.[59] But panic sales continued, and by March, Wines and Vines reported "cut throat competition at the retailer level" and described ads from regional newspapers that showed wines "being sold at unprofitable figures."[60] In California, the industry attempted to stabilize prices by extending beer "fair-trade" price-posting to wine.[61] Essentially, "fair-trade" required that minimum prices for bottled wine at the wholesale and retail levels be posted with the state each month for every brand. Since prices could be changed only once a month, "fair-trade" slowed price cutting. The price-postings were also public documents, so everyone in the industry could quickly know the price of competing brands.

Although fair-trade helped set a bottom for some brands, it did not stop the slide in bulk wine prices. By June, dessert wine was selling at 40 cents a gallon, roughly 20 percent of its high a year before. Standard table wines fell almost as far, down from $1.30 a gallon to 30 cents.[62] The price drop was huge, and it has been estimated that Schenley and National Distillers, who had been the major bidders for grapes in 1946, lost $11 million and $9 million dollars respectively in the debacle.[63] They were not alone. Only a handful of producers emerged unscathed; most were seriously hurt, and a few were driven to bankruptcy or liquidation.

The crush of 1947 was a dismal affair, more reminiscent of the prewar years than of the past four years of prosperity. Grape prices tumbled to between $30 and $35 dollars a ton, and would have fallen further except for the Department of Agriculture's purchase of 121,000 tons of raisins for shipment to Europe, which diverted roughly 15 percent of the total grape crop.[64] Some growers entered into "share-crushing" agreements with wineries in which the winery agreed to crush the grapes, but the grower's return would be based on the selling price of the wine. Other growers banded together to create new cooperative wineries or to lease existing wineries to crush and ferment their grapes. In either case, grow-

ers were gambling on increased wine prices, since wine prices in the fall of 1947 translated to about $30 a ton.[65] The irony was that the 1947 growing season was the best in a decade, with "almost perfect" growing and harvest weather, but with little demand for grapes.[66]

The fall in wine and grape prices in 1947 marked the end of the period of war-induced prosperity and the transition to a new postwar economy in which supply and demand would be driven by the market, rather than by government regulation. The boom from 1943 through 1946 had proved short-lived, but it was nonetheless pivotal to the future of California wine. In four short years, the California industry had changed from production of a bulk commodity to predominantly brand-oriented business. At-winery bottling could not be undone, and producers would more and more also have to become marketers if they were to succeed. The controlled economy of the home front had proved that Americans would drink wine. The task that lay ahead was to increase per capita consumption of California wine in an unregulated economy.

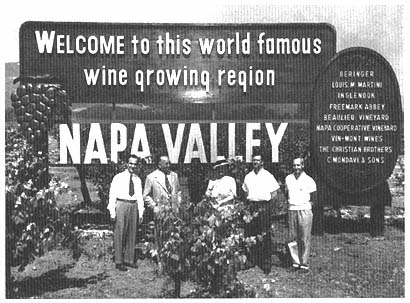

DEDICATION OF SIGN BY THE NAPA VALLEY VINTNERS' ASSOCIATION.

JUNE 30, 1950. Original photo from Napa Wine Library. In an act of

regional promotion, the NVVA erected this sign in late 1949, the sequence

of members' names on it being determined by lot. Winemakers pictured in

the dedication are, from left to right, Robert Mondavi (C. Mondavi and

Sons/Charles Krug), Charles Forni (Napa Cooperative Vineyard), Madame

Fernande de Latour (Beaulieu Vineyard), John Daniel, Jr. (Inglenook), and

Al Huntsinger (Vin-Mont was the brand name for the Napa Cooperative

Winery, the so-called "Big Co-op").

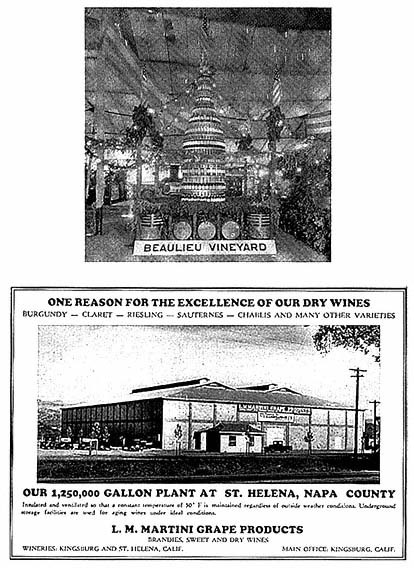

BEAULIEU VINEYARD DISPLAY AT 1934 VINTAGE FESTIVAL . California

Grape Grower , September 1934. Befitting its dominant position in the

Napa Valley, Beaulieu arranged for a multitiered display that towered

over those of other wineries at the 1934 Vintage Festival.

THE L. M. MARTINI WINERY,ST. HELENA, IN 1935 . Wines and Vines ,

June 1935. The Martini winery was the first new winery built in the

Napa Valley since the beginning of Prohibition. With insulated walls

and a fermenting room cooled by mechanical refrigeration, the winery

was reminiscent of a Central Valley processing plant and was the

technical leader in the Napa Valley at Repeal.

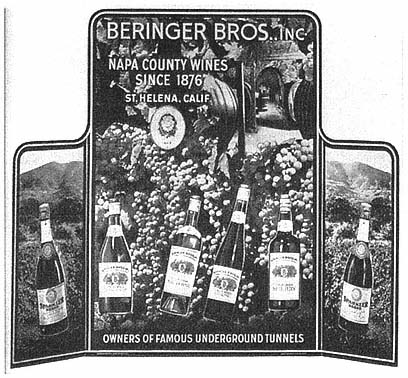

BERINGER POINT-OF-SALE DISPLAY . Wine Review , December

1937. In this 1937 six-color dealer display, Beringer

played on the romance of wine, the beauty of the countryside,

its long history in the Napa Valley, and its "famous underground

caves." Typical of the time, only one of the six bottles

displayed was labeled as a varietal wine.

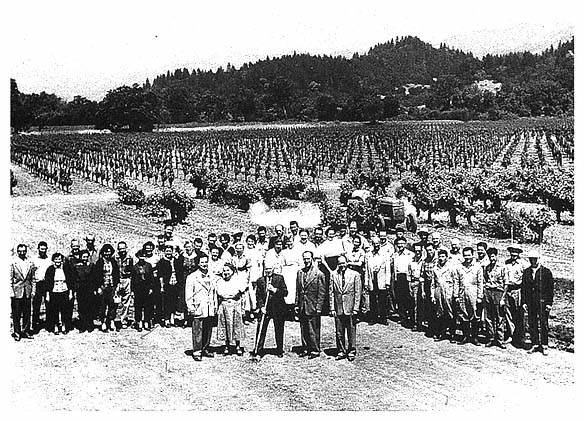

CHARLES KRUG GROUNGBREAKING . Photo: Julie Dickson. During the 1950s, the Charles Krug winery,

operated by C. Mondavi and Sons, emerged as the technical leader in the Napa Valley. When increased

volume and new technology necessitated a new warehouse and bottling line, the entire winery

staff turned out for the 1958 groundbreaking. In the foreground from left to right are Peter Mondavi,

Rosa Mondavi, Cesare Mondavi, Robert Mondavi, and an unnamed contractor. Note the head-trained

vines in the background.

(Top)GENERIC AD FOR CALIFORNIA WINE . Wines and

Vines , May 1939. The Wine Advisory Board's mission

was to promote California wine. This 1939 advertisement,

designed to appear in national magazines and regional

newspapers, is an excellent example of the static and

generic print-media-oriented promotion later criticized by

California's quality producers.

(Bottom) "SERVE IT COLD ." Wines and Vines , May 1941.

This generic Wine Advisory Board advertisement, designed to

promote wine sales during the traditionally slow summer months,

was the featured cover of Wines and Vines in May 1941.

Note the use of a European place-name to describe a

California product.

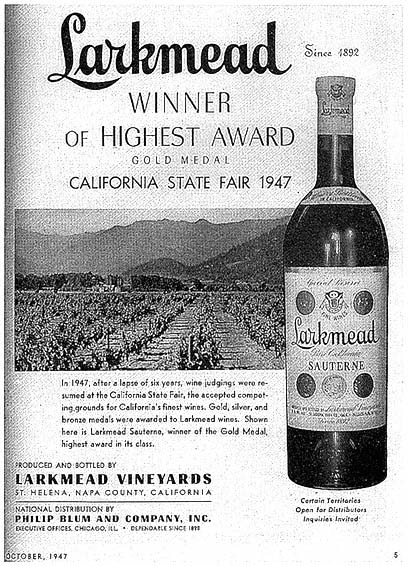

LARKMEAD ADVERTISEMENT . 1947. Wines and Vines , October 1947.

Larkmead was one of the original quality producers following Repeal,

but was sold to a midwestern partnership during World War II. This ad

from October 1947 appeared just in time to coincide with the crash in

wine prices that followed the 1947 harvest and the reappearance of

blended whiskey in the marketplace. Two months later, Philip Blum

and Co., which owned numerous distilling interests, was bought by

National Distillers, owners of Italian Swiss Colony, and Larkmead

became a crushing station for Italian Swiss Colony, until shut

down in the early 1950s.

CHARLES KRUG BILLBOARD . Wine and Vines , April 1946. Following World

War II, the Mondavis began active promotion of their top brand, Charles Krug.

This 1946 billboard promoted the pairing of quality and region and played

on the fact that theirs was the "oldest" winery in the Napa Valley.

BOTTLES AND BINS MASTHEAD . Shields Library. In 1949, in an attempt to build

a direct relationship with wine consumers, the Charles Krug winery launched

the first winery newsletter in California, soon to be followed by Almaden.

Worldly and witty, Bottles and Bins helped introduce California wine to

postwar America.

NAPA VALLEY VINTNERS' ASSOCIATION CABLE CAR . Napa Valley

Wine Library. In October 1949, the NVVA sponsored a San Francisco

cable car for a year, giving a bottle of Napa wine each day to a

lucky passenger. Member wineries were listed on the front

of the car.

HARVARD CLUB LUNCHEON WINE LIST . Napa Valley Wine Library. In 1949

the Napa Valley Vintners' Association took advantage of the Harvard Club's

meeting in San Francisco to introduce members to the charms of Napa

wines at a sit-down luncheon held on the Charles Krug winery grounds.

The Harvard Club lunch was the first of many mass tastings for upper-

class Americans held by the NVVA, and the idea was later imitated

on a larger scale by Premium Wine Producers of California in

conjunction with the Wine Advisory Board. The twelve-page menu

souvenir booklet was prepared by the fine-arts printer Jim Beard.

The winemakers presented their best wines, and even in 1949,

varietally labeled wines predominated.

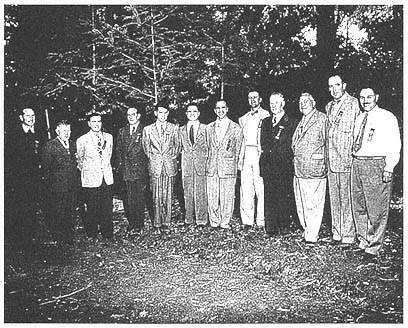

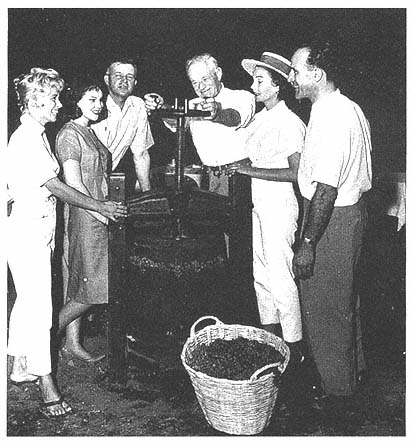

NAPA WINEMAKERS AT HARVARD CLUB LUNCHEON, SEPTEMBER

1949. Napa Valley Wine Library. Members of the Napa Valley Vintners'

Association posed for a group photograph at the Harvard Club

luncheon. From left to right: Brother Timothy of Christian Brothers;

Charles Forni of both the Napa Valley Cooperative Winery and the

Napa Cooperative Vineyard; Walter Sullivan and Aldo Fabbrini of

Beaulieu Vineyards; Mike Ahern of Freemark Abbey; Peter

and Robert Mondavi of C. Mondavi and Sons (Charles Krug);

John Daniel, Jr., of Inglenook; Louis M. Martini of the L. M.

Martini Winery; Charles Beringer of Beringer Brothers; Martin

Stelling, Jr., of Napa Cooperative Vineyard (Sunny St.

Helena); Fred Abruzzini of Beringer Brothers.

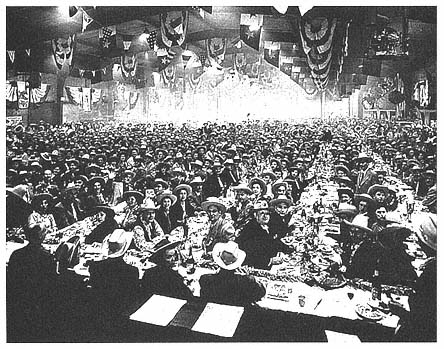

GENERAL ELECTRIC BARBECUE, FEBRUARY 1952. Napa Valley Wine Library.

Reaching out to potential higher-income consumers, the Napa Valley

Vintners' Association sponsored tastings and luncheons for groups

visiting San Francisco. At this western-theme barbecue, the NVVA

entertained two thousand General Electric managers at the Napa

Valley Fairgrounds.

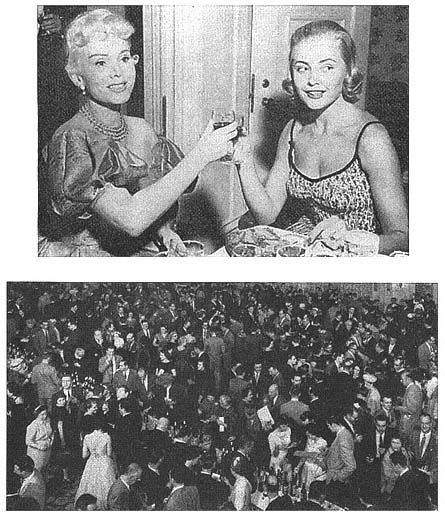

ZSA ZSA GABOR AND HILLEVI RUBIN ENJOY CALIFORNIA WINES . Wines and

Vines , November 1956. A public relations campaign was launched in the mid

1950s to persuade affluent postwar Americans that California wine was part of an

attractive, successful lifestyle. This 1956 photo of the actress Zsa Zsa Gabor and Miss

Universe, Hillevi Rubin, taken at a blind tasting held at the Hollywood Foreign

Press Club, was estimated to have reached over forty million Americans.

MASS TASTING IN ST. LOUIS, 1959. Wines and Vines , March 1959. By the mid

1950s, California quality producers had demanded that the Wine Advisory

Board shift from generic, print-oriented advertisements to a more dynamic form

of promotion based on public relations and direct contact with potential consumers.

This mass tasting held in St. Louis has obvious parallels with other tastings hosted

by the Napa Valley Vintners' Association earlier in the decade, such as that for

General Electric. Unlike generic advertisements, mass tastings allowed specific

brand promotion by giving consumers a chance to taste hundreds of

California wines.

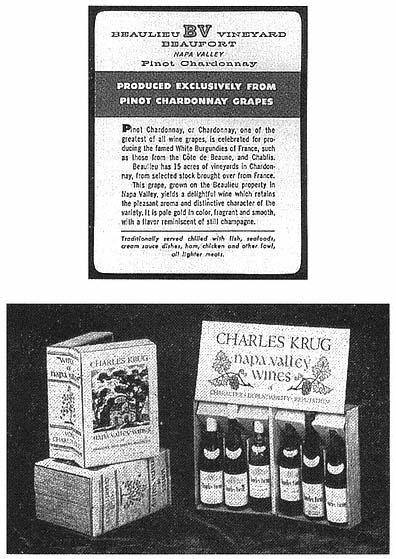

BV BACK LABEL . Wines and Vines , June 1956. Beaulieu took a new step in

consumer education and brand differentiation in 1956 when it introduced

this back label describing "Pinot Chardonnay." Beaulieu had only

fifteen acres planted, which might have produced between

3,000 and 4,000 cases.

CHARLES KRUG CHRISTMAS JPGT PACK . Wines and Vines , December

1959. The Mondavis built on the success of Bottles and Bins to market

a special Christmas "volume" of Charles Krug wines to newsletter subscribers,

who found the attractive package of six "tenths" a unique upscale gift.

The sample was designed by Malette Dean and Jim Beard.

THIS EARTH IS MINE . Napa Valley Wine Library. In 1958, Universal Pictures

and Rock Hudson traveled to the Napa Valley to film This Earth Is Mine , a

loose adaptation of The Cup and the Sword , a novel based on the life

of Georges de Latour. Napa winemakers were never shy about seizing on a

promotional opportunity, and three of them, John Daniel, Jr., Louis M.

Martini, and Robert Mondavi, posed with the film's actresses. Louis

Gomberg, who had helped create Premium Producers of California,

helped secure financing for the film.

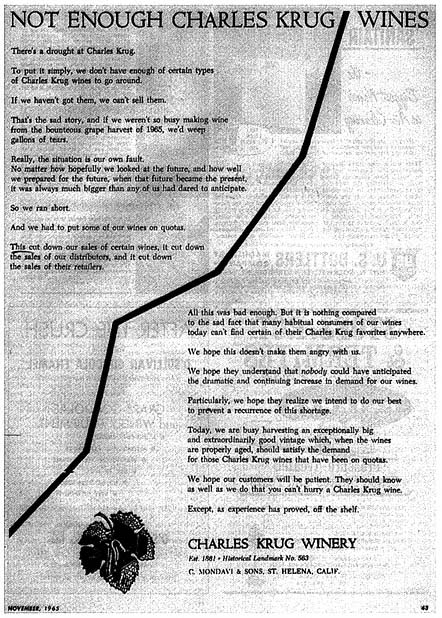

"NOT ENOUGH CHARLES KRUG WINES."Wines and Vines , November 1965. By

1965, the "wine boom" had begun, and supply could not keep up with demand.

Other wineries experienced similar problems, but the Charles Krug Winery, in

an ad aimed primarily at distributors and retailers, used the shortage to

underscore its amazing growth over the past decade.

BEAULIEU WINERY . Photo: Beaulieu Winery Public Relations Department.

This photograph of Beaulieu looking east across Highway 29 was taken

before 1941 and the erection of the administrative "tower" at the northern

end of the building. The rail spur still exists, although it is no longer used.

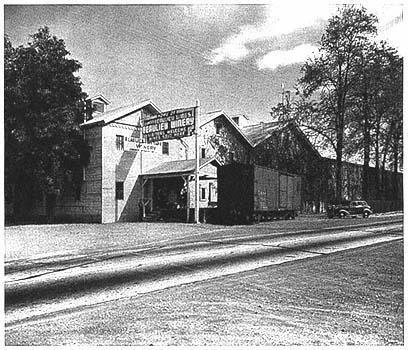

LARKMEAD . Photo: John Gay. Larkmead was one of the "big four" wineries after Repeal.

This photograph from the Salmina family, probably taken during the 1930s, depicts a scene

typical even of quality producers: a rail car and barrels ready to be loaded and shipped

east to regional bottlers.

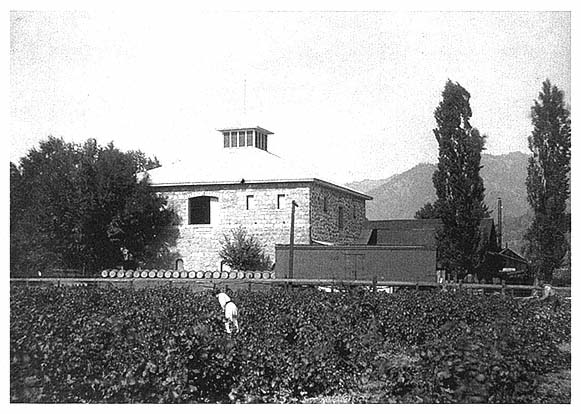

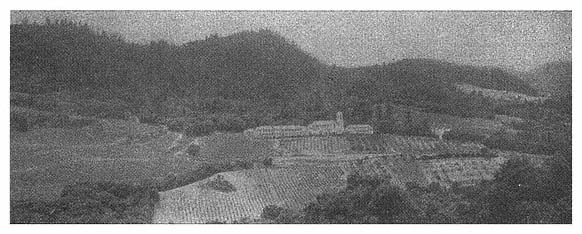

MONT LA SALLE / CHRISTIAN BROTHERS . Wine Review , December 1939. Following Repeal,

Christian Brothers moved from Martinez to the old Gier Winery on the slopes of Mt. Veeder

above the city of Napa, which became known as the Mont La Salle Winery, after St.

Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, founder of the Christian Brothers order. After buying a winery

and distillery in the Central Valley, and later the Greystone facility north of St.

Helena, Christian Brothers became one of the top suppliers of table wine

in the 1950s.