The Vitascope Group

In a number of crucial respects, the Vitascope organization was typical of film companies as the novelty era began. It manufactured its own equipment and made its own films. In addition, it retained control over exhibition as well as production. In fact, the four leading rivals had incompatible technologies— the vitascope, eidoloscope, cinématographe, and biograph—and thus each company had to operate in a self-contained fashion. However, the Vitascope organization was uniquely burdened by a loose affiliation of individuals and groups, whose interests often did not coincide. At the center was the Vitascope Company, incorporated by Norman Raft, Frank Gammon, and James White (as the third member of the board of directors, with one share of voting stock) in early May.[47] (This was one indication that the stockholders of Raft & Gammon's old Kinetoscope Company were not to play a part in this new enterprise. In fact, it was soon liquidated.) Raft & Gammon acted as a clearing house for the entrepreneurs, who had bought exclusive exhibition rights at considerable expense. As these owners were desperately trying to recoup their investment, they had little sympathy for, or understanding of, the company's problems. Raft & Gammon, moreover, did not control the Edison Company's activities and could only plead for quick action. Thomas Armat and T. Cushing Daniel, with their patent applications, were yet another affiliated organization. Although the coordination of these groups sometimes presented awkward problems, vitascopes served as the principal purveyors of moving pictures in the United States throughout the summer of 1896. The number of available machines, the comparative variety of films, the Edison name, and the hard work of the states rights owners assured a rapid, nationwide diffusion of this novelty.

Raft & Gammon's principal commercial strategies worked on two levels. First, they sought an immediate windfall by selling off the exclusive exhibition rights for specific territories (known as "states rights") to entrepreneurs, with publicity generating interest and raising the price. The sale of rights then bound these investors to the Vitascope enterprise. As Raft explained to Armat, "After

our territory is once sold, we need have but little fear about future business. After the purchasers of territory have their money invested, nothing will prevent their going ahead, and they will co-operate with us against all possible competitors and against untoward conditions and circumstances."[48] Thus, long-term profits would be achieved by renting machines to the states rights owners for $25 to $50 per month and through the sale of films.

States rights was considered a particularly effective way to deal with the threat presented by competing machines. This long-term strategy, however, was premised on controlling the exhibition field through Armat's patents—on which applications had been made but not yet granted. At best, such aid was in the distant future. During the interim, the goodwill and cooperation of the Edison Manufacturing Company were crucial.

In a long, often redundant, letter to William Gilmore, Raff outlined those areas in which Edison Company assistance was sought: good workmanship in the manufacture of vitascopes, prompt service, easy access to a camera and operator, exclusive ownership of films that they financed (so continuing an already established arrangement), and a promise not to sabotage the Vitascope Company by marketing a competing machine.[49] Raff's deference of tone, his frequent reference to moral obligations, and his eagerness to share profits with Edison and Gilmore all underscore the Edison Company's crucial role. This obeisance must also be placed against the background of Edison's business dealings in the closely related phonograph industry where he had just (February 1896) forced the North American Phonograph Company into bankruptcy. The investors in the old company plus the various owners of states rights either folded or, as in the case of the Columbia Phonograph Company, lost the special benefits of their investment. Edison then replaced the defunct company with the new National Phonograph Company under his immediate ownership. As Robert Conot has remarked, such activities gave Edison the worst image in this associated industry.[50] Moreover, if Edison chose to assume direct control over the phonograph, why not over moving pictures? Raft & Gammon never explicitly asked this unsettling question in their correspondence, but it was obviously on their minds. Nor did they apparently receive any reassurances. For the moment, Edison cooperated because Raft & Gammon were extremely useful and served both his reputation and pocketbook. In the longer term, Edison self-interest would prevail.

In the end, vitascope rights were sold for virtually every state outside the Deep South. Owners of these states rights came from a variety of backgrounds. Many had exhibited the phonograph and/or kinetoscope and were anxious to continue a profitable association with Edison. Others had a background in electricity and were ready to continue their Edison association but move into the entertainment field. A few had either theatrical experience or been otherwise

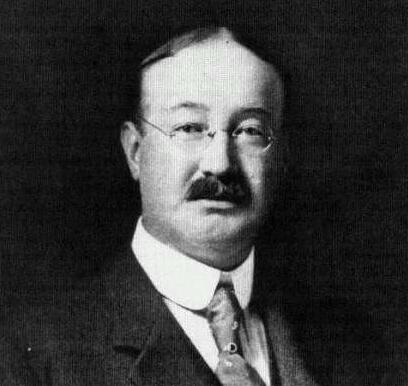

William E. Gilmore.

active in the field of popular amusement. A significant number of the Vitascope entrepreneurs had no relevant background, however, but were small businessmen hoping to strike it rich on Edison's latest novelty.

States rights owners had several ways to make a return on their investment. Typically, owners acted as exhibitors, providing a selection of films, a projector, and an operator. This package was commonly offered to theaters for a fee, usually several hundred dollars a week. In other circumstances, these exhibitors either rented a vacant storefront and kept any profit above expenses or presented films at a hall and divided receipts with its manager. A few leased subterritories to amusement managers who wanted complete control over their shows. Several historians have offered useful overviews of the experiences of these "pioneers," but focusing on the activities of one group of individual entrepreneurs is another way to understand the opportunities and difficulties faced

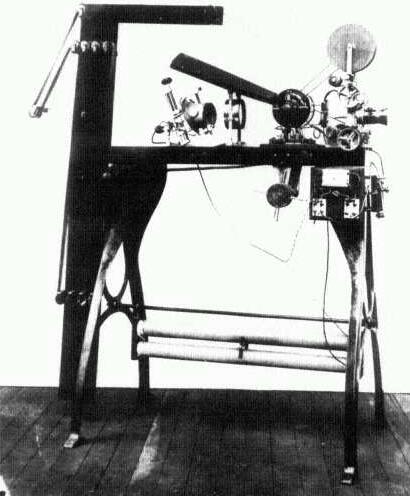

One of the first vitascopes.

by these early exhibitors.[51] What were their backgrounds? How did they come to acquire the rights? How did they try to exhibit this novelty and what kind of reception did it enjoy? The next section will address these questions by looking at the group based in Connellsville, Pennsylvania, with which Edwin Porter was deeply involved.