Magdalena Aulina, the Mystic from Banyoles

The Vallet followers in Barcelona met in their social center, a downtown mansion known as the Casal Donya Dorotea. There García Cascón lectured on Ezkioga and there early in the previous year another industrialist had brought Magdalena Aulina i Saurina to tell of her miraculous cure and to speak about her new religious society.[48]

For Galgani see Boada, "Flors de santedat"; for the Casal see Sospedra Buyé, Per carrers, 348-359, 423-448, and EM, 1 July 1930.

Developing religious orders drawn into the Ezkioga orbit got a boost of religious enthusiasm. But all came to regret the connection. Magdalena Aulina's institute obtained approval from Rome with great difficulty in 1962, and her successors in the Señoritas Operarias Parroquiales find it difficult to speak about the inspiration of Gemma Galgani and the trips to Ezkioga. They wished me to make clear that the institute existed before the visions at Ezkioga and was quite independent of them.

Magdalena Aulina was born in 1897, the daughter of a wood and coal dealer in the market and summer resort town of Banyoles (Girona). From an early age Magdalena had accompanied her sister, later to become a cloistered Carmelite, in works of charity among the poor. In 1916 she organized a Month of Mary for the children in her neighborhood and later a parish catechism group. By this time she was sure that she had a religious vocation. In part she was inspired by Gemma Galgani, a young woman from Lucca who died at age twenty-five in 1903 after a life dense with mystical phenomena. In 1912 Magdalena read Gemma's biography. In 1921 at age twenty-four Magdalena recovered from a heart condition after a novena to Gemma. This cure confirmed in her mind her spiritual link with the saintly Italian.[49]

Information on Magdalena Aulina i Saurina (b. Banyoles, 12 December 1897-d. Barcelona, 15 May 1956), unless otherwise noted, is from her successor, Filomena Crous, Barcelona, 25 and 27 February 1985, and ephemeral literature she kindly provided, particularly "Discurso de la directora general, bodas de oro del instituto y décimo aniversario de nuestra madre fundadora ... 24 mayo 1966," 17-page typescript.

The early twentieth century was an era of well-publicized miraculous cures at Lourdes. Very early on, the Barcelona pilgrimages prepared clinical dossiers to present to the Lourdes medical commission in case a cure should occur, and the Annales of Lourdes record several cures of Catalans. Those cured became living proof of the Virgin's power and indeed of the existence of God in a doubting world. Miracles invested those cured with charisma. Aulina's cure

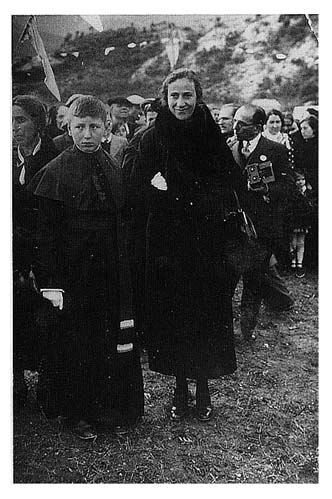

Magdalena Aulina with nephew of Gemma Galgani

at the Banyoles "Pontifical Fiesta," at which the first

stone was laid for a monumental fountain to Galgani, 1934

brought her respectful visitors and she told them about Gemma Galgani's help. Banyoles was the headquarters of diocesan parish missioners, and they too spread the word.[50]

Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 13, 163.

The year after Magdalena's cure, in 1922, with the aid of industrialists who were summer residents, she founded a kind of social house in Banyoles for women workers. In 1926 she helped to build a church in her neighborhood and organized a literacy program. She assisted Vallet when he gave parish exercises in Banyoles, and it is possible that he had her in mind to form an order of nuns to assist his movement.[51]

In 1922 Aulina was at Montserrat representing "Patronat d'Obreres de Banyoles" (La IIIa Assemblea de la federació de patronats d'obreres de Catalunya a Monserrat, 1, 2 i 3 d'abril de 1922 [Barcelona: Impremta Editorial Barcelonesa, 1922]).

Aulina had plans of her own, however, and more than enough contacts to put them into practice. At a meeting of Catholic social workers in 1929 at

Montserrat, she met Montserrat Boada, a member of a wealthy Barcelona family with influence in the Vatican. Through the Boadas and similar families, Aulina found support in exactly the same social stratum as Vallet had. When in early 1930 she told Vallet's supporters at the Casal about her spiritual link to Gemma Galgani, she made a deep impression. Shortly afterward José María Boada praised Gemma in the group's magazine, concluding, "Let us let her lead us sweetly through the paths of life."[52]

Boada, "Flors de santedat," 225.

Gemma Galgani seemed to speak through Aulina, who acted more like a spirit medium than a seer. For instance, Cardús was present once at Banyoles when Gemma spoke through Aulina of the future of the institute. Thus, to follow Gemma was in effect to follow Aulina; through Aulina, believers sought Gemma's help in matters both ethereal and mundane.[53]

Aulina's spiritual directors included Angel Soquer, the parish priest of Banyoles; José María Carbó, a canon of Girona; Fulgencio Albareda, a Benedictine of Montserrat; and finally Marcelino Olaechea, a Salesian who was bishop of Pamplona in 1935 and in 1946 archbishop of Valencia.

By 1931 some unmarried young women lived with Aulina in Banyoles fulltime, and three of them took the first private vows of chastity, poverty, and obedience in 1933. On weekends entire families of supporters would come to stay in Magdalena's house, the houses of relatives, hotels, and rented quarters. The supporters were typically doctors, industrialists, and lawyers from Barcelona, Girona (where the group had a clinic), Reus, Terrassa, Sabadell, and Tarragona. Visitors would remark on the sumptuousness of the religious services, with massed choristers in robes and much incense; every Sunday seemed a high feast. Those privileged to dine with Aulina might see her go in and out of trance at the table, as Cardús did, or even watch her in struggle with the devil.

José María Boada helped to persuade Aulina to send regular "expeditions" to Ezkioga. When he heard the praise that seers like Benita passed on from the Virgin about Pare Vallet, he went to Ezkioga to obtain more details. It may be that the seers led Boada to think that he himself had a divine mission; on December 9 Garmendia claimed to see the Virgin on his arm. After Boada reported back to Aulina and Aulina consulted Gemma's spirit, the Casal Donya Dorotea expeditions began on 12 December 1931. Two weeks previously the pope had read in Rome the official proclamation of Gemma's heroic virtues, a stage in the process of beatification, so there was a spate of articles about Gemma in the press which doubtless increased the fervor of Aulina's followers.[54]

SC E 193, 230, 236; Gratacós, "Lo de Esquioga." Gemma Galgani articles, all 1931: EM and CC, 2 December; CC, 11 December; Hormiga de Oro, 17 December; EM, 18 December.

Bartolomé de Andueza, the Rafols enthusiast, was aware of the role of Aulina and Gemma in the trips. In March 1932 he wrote in La Constancia of

the very devout expeditions of Catalans that arrive at Ezquioga weekly to do penance under the patronage of the angelic Gemma Galgani. They were suggested to their organizers by a soul in Barcelona living an extraordinary life who emulates the Italian virgin and has "inherited her spirit."[55]

LC, 11 March 1932.

There were eventually twenty-five trips of twenty-four to thirty persons. All included a lay "director" who led prayers (often Boada) and a technical manager, Luis Palà of the Casal. And, despite the prohibitions of the diocese of Vitoria,

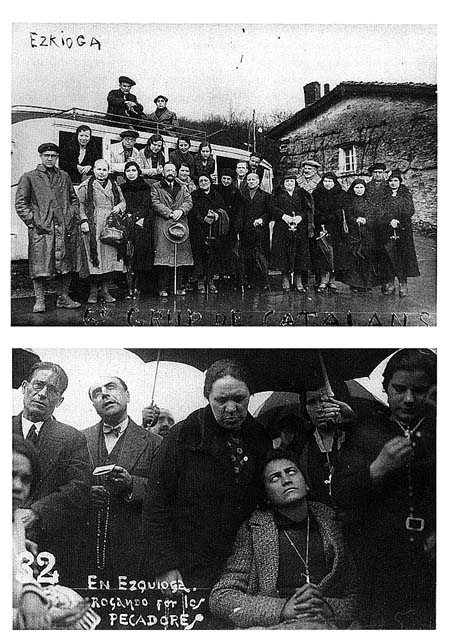

Top:The sixth Catalan expedition to Ezkioga, 8 March

1932; the politician and writer Mariano Bordas holds a hat.

Bottom: José María Broada, with eyes upturned, leads

prayers for sinners, winter 1932. Photos by Joaquín Sicart

there was a priest on most trips. Arturo Rodes Buxados, who went four times, acted on his own as a chronicler. Cardús and García Cascón were not core members of the group, although both for a time became devoted to Aulina-Gemma and both spent periods at the Banyoles complex. The trip took a day and a half each way, and the pilgrims spent four days at the site, staying at the Hotel Urola in Zumarraga. They maintained files of cures and visions and, following the practices of the Parish Exercises movement, posed for group photographs as a public witness of their commitment as Catholics.[56]

I have not seen the documents, now presumably in the Aulina archives. But Burguera included many of them in his book. My other main sources are the manuscript of Arturo Rodes, the diary of Cardús, and the account of the first trip by Luis Gratacós (and José María Boada), "Lo de Esquioga."

The trip members often prayed for as many as eight hours on the hillside, and some evenings for two hours more in the hotel. To outsiders their effusive piety seemed showy. The Piarist priest Marc Lliró of Barcelona watched Boada and Palà lead prayers at Ezkioga and later wrote disapprovingly: "Piety is not ridiculous, or tiresome, or exaggerated, or different from a peaceful normality. At Ezkioga it seemed to me … I found these kinds of false piety."[57]

Marc Lliró to Cardús, Barcelona, 10 October 1932.

Aulina's mysticism spilled over to her followers in other ways. Many of them perceived a perfume on the bus trips and at other significant moments in their daily lives. Often a majority of passengers perceived the scent simultaneously, and to avoid confusion women did not wear perfume or cologne. They understood the scent as a sign of approval from Gemma. For these pilgrims Providence charged every moment of the trip and there was no place for chance. At least a dozen of the six hundred or so expedition members had visions at Ezkioga. Others were converted or cured.[58]Lourdes Rodes, Barcelona, 29 November 1993; B 373-376.

From the start these pilgrims cultivated the seers García Cascón and Boada had come to trust. They would pick them up in the morning and take them to the vision site. There they would have a private vision session. After lunch at the hotel, they would return the seers to the site for late afternoon prayers and then they would take them home. Often seers would also have visions on the bus. The seers quickly incorporated Gemma, as they had Madre Rafols, into their visual repertoire. At the end of October 1931 a Catalan assured the teenage seer Cruz Lete that if he said a novena and promoted devotion to Gemma, she in turn would set things straight at Ezkioga (presumably restore the credibility of the seers, damaged by the Ramona episode). When Lete finished the novena on November 17, he began to see Gemma Galgani in his visions. The Catalans worked to convince the seers that, as Cardús wrote in a letter, "Everything, everything, Ezkioga, Madre Rafols, and Gemma, are all the same thing."[59]

On Cruz Lete see ARB 79, 214. Other visions of Gemma by seers in 1931: Benita Aguirre, December 14, ARB 10; Cruz Lete, December 15, ARB 12-13; María Recalde, December 29. In 1932: Luis Irurzun, February 25; Jesús Elcoro, March 14; Loreto Albo, April 5, ARB 109; Benita Aguirre daily in March and June (Benita to García Cascón, 22 May, and SC D 111-112); Luisa Sabaté in bus, August 24, ARB 115. There were many others from 1933 to 1935. Quote is from Cardús to J. B. Ayerbe, 11 October 1933.

The seers nourished the sense of Providence in these pilgrims. Evarista Galdós predicted that certain of them would have visions, told others they would smell the scent of Gemma, and revealed to a young man his secrets. José Garmendia picked out the only doubter in one group, interceded with the Virgin to remove the devil from one Catalan's visions, and divined the secret prayers of a young Catalan male. On three occasions he pointed out trip members who would be seers.

Garmendia's greatest success was with García Cascón's servant of six years, Carmen Visa de Dios, who went on the trip from 20 to 22 June 1932. Garmendia privately told two trip members that Visa would be a seer and all the members then signed his sealed prediction. The next day while Garmendia was having his vision, Visa had hers. She was a widow, age forty-seven, from Torrente de Cinca (Huesca). Her visions at Ezkioga were of Christ Crucified and the Sorrowing Mother, and for most of the return trip she saw Gemma Galgani hovering like a bird outside or on the hood of the bus. When the pilgrims offered Gemma prayers, Visa saw her nod in response, and as she saw Gemma say farewell on the outskirts of Barcelona, many members said they smelled the Gemma scent.[60]

B 630-635; ARB; SC D. For Visa, SC D 145-174; ARB 114-117; B 635; copy of expedition document, "Visions de Carme Visa de Dios, tingudes els dies 21 y 22 de juny de 1932," 8-page typescript, ASC. Visa had had an earlier vision in Terrassa on 24 October 1931 while her employers were at Ezkioga, and when she returned she had more in the house. She died 10 October 1932.

Benita Aguirre, like Garmendia, interceded for Catalans with the Virgin. From the start she was the group's favorite seer, both because of earlier publicity and because of her message about Pare Vallet. Of the six sessions on the hillside of the first trip, Benita was the central figure in five. Right away the pilgrims invited her to visit Barcelona.

Like previous Catalan observers, the chroniclers of this trip admired her stance in vision. On the afternoon of December 15, as on earlier occasions, the Catalans had given her objects for the Virgin to bless. She laid out the crucifixes in front of her on the vision deck and draped the rosaries on her arms. According to a youth who was present, she then fell face forward and sat up again,

leaning slightly backward, resting in the arms of my friends, her head slightly raised, her eyes fixed on a point high up, but not so fixed that they did not move somewhat or blink occasionally. She speaks with the apparition; she smiles, suffers, sobs, but without tears, asks forgiveness with a sad and tender voice. Then she bends and takes one by one the objects lined in front of her, and each time raising her arm, presents them to the apparition to kiss and bless them. I have a crucifix about a palm long I bought there that Benita held in her hands that afternoon. It was kissed by the Virgin, Gemma (whom she saw again today), and the angels. I also have three red rosaries. The medals on the safety pin I wear were kissed by the Virgin and Gemma. All this as said by Benita.

The youth describing the trip had already stocked up on blessed objects at the two sessions with Benita he attended the previous day. In the morning he had obtained blessings for "three men's rosaries, twenty medals, a miniature image of the Virgin the nuns at Llivia gave me, and a small crucifix that belonged to my mother," all kissed by the Virgin and Gemma. In the afternoon he had "five black rosaries, with smaller beads" kissed by the Virgin, Gemma, and the baby Jesus. He wrote his aunt, "I'll send you some of each." He paid little heed to grand messages of chastisements and miracles scheduled for an indefinite future. As at Limpias a dozen years before, pilgrims were interested in the here-and-now, in resolving spiritual problems and obtaining holy souvenirs.[61]

Gratacós, "Lo de Esquioga," 17-18, 14.

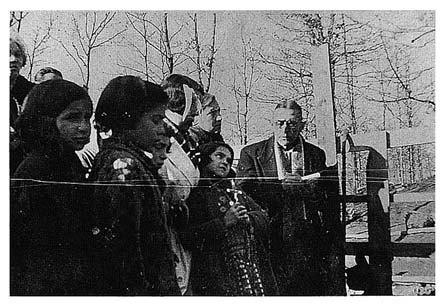

Benita Aguirre raising object to be blessed for Catalans,

ca. 28 February 1932. Photo by Joaquín Sicart

In mid-March Benita went to Barcelona in the group bus and stayed for three days. The group received her enthusiastically at the Casal. And Magdalena Aulina, it seems, enrolled her as a "Servidora de María" in the Obra. At Montserrat the dark Madonna did not impress her. Her Virgin, she said, did not look like that! She stayed with the Rodes family, and Lourdes Rodes, age nineteen, gave Benita her oversize four-foot doll.[62]

ARB 45-46, 245-247; letter from García Cascón to female seer, probably María Recalde, 24 August 1933, private archive; Vitoria Aguirre, Legazpi, 6 February 1986, p. 13. For more on Benita and the Catalans, ARB 48, 89-90, 97-98, 134.

Lourdes Rodes finally got to go to Ezkioga from April 29 to May 4, and there, as Benita's father sheltered them from the rain with an umbrella, she supported Benita in vision. The experience was a spiritual one Lourdes remembered vividly over sixty years later:

Benita was looking upward and speaking in Basque while a man translated and my father took notes. I was filled with an intimate feeling of peace and tranquillity, like a ray of sunlight that warmed me. When the vision went away that feeling stopped. I was left very deeply moved and wanted to cry with happiness.[63]

Lourdes Rodes, Barcelona, 29 November 1993, p. 2.

Later, when Benita could no longer stay in Legazpi, Catalonia proved to be a second home, for she won the hearts of its pilgrims. A clerical observer of an expedition wrote in early October 1932, "I felt sorry for these people who, it seemed to me, believed more in Benita than in the mysteries of the faith."[64]

Lliró to Cardús, Barcelona, 10 October 1932.

Benita Aguirre in vision next to Arturo Rodes with his

notebook, 14 December 1931. Courtesy Lourdes Rodes Bagant.