Retinal Art and Conceptual Euphoria

Art is a mental thing.

—Leonardo da Vinci

Quel Siècle à mains!

—Arthur Rimbaud

Duchamp's explicit rejection of painting as a purely visual medium whose purpose is to incite "visual euphoria" must be taken, like his other pronouncements, with a grain of salt. Duchamp's objections to painting are strategic, rather than purely oppositional. They are less a statement of denial of the significance of pictorial traditions, than an effort to rethink the legacy of painting in conceptual terms. In an interview with Francis Roberts, Duchamp clarifies his position by affirming his interest in innovation, that is, an "ideatic" interpretation of visual painting:

In France there is an old saying, "Stupid like a painter." The painter was considered stupid, but the poet and writer very intelligent. I wanted to be intelligent. I had to have the idea of inventing. It is nothing to do with what your father did. It is nothing to be another Cézanne. In my visual period there is a little of that stupidity of the painter. All my work in the period before the Nude was visual painting. Then I came to the idea. I thought the ideatic formulation a way to get away from influences.[9]

Duchamp's commitment to "intelligence" that he associates with poets and writers reflects his effort to redefine pictorial language in new terms. Rather than remaining subject to the constraints of pictorial language, even when its figurative limits are strained and questioned through the emergence of abstraction by painters such as Cézanne, Duchamp challenges visual representation by exploring its conceptual, "ideatic" character. Duchamp's effort to innovate, that of "inventing a new way to go

about painting," cannot be seen purely as a dismissal of pictorial traditions. At issue is the question of rethinking the concept of innovation in terms that amount to new ways of drawing on pictorial traditions, thus enabling the rediscovery of art's conceptual potential.

The affinities between Duchamp and Leonardo da Vinci have been noted by Theodore Reff, particularly regarding their shared conviction that "art is primarily the record of an intellectual process rather than a visual experience."[10] This emphasis on intellectual rather than visual experience explains why both artists were "more concerned with formulating their ideas than with producing finished paintings, more excited by research than execution."[11] This interest in research, in the effort to rethink the relationship between science and art, is visible in Duchamp's extensive notes, which were published in exact replica, starting with The Box of 1914 (1913–14), which anticipates the project of The Large Glass, The Green Box (1934).[12] His initiative to publish them may have been inspired by the publication of Leonardo's notebooks in facsimile (circa 1900), as well as by Paul Valéry's seminal work, Introduction to the Method of Leonardoda Vinci (1894).[13] Like Leonardo's notebooks, Duchamp's boxes include sketches, notes, and word associations. Duchamp eventually includes in his boxes reproductions of his own works, however, thereby transforming the provisional status of boxes into actual works. These boxes document not only his research and technical efforts but also his thought processes, combining artistic and poetic methods. Rather than functioning merely as research prototypes, Duchamp's notes, sketches, and reproductions represent an effort to challenge the notion of the work of art as an objective product by redefining it as a process, the embodiment of intellectual, artistic, and technical methods. Anne d'Harnoncourt and Walter Hopps consider these compilations as "masterworks in themselves, as important as any of Duchamp's realized visual projects, perhaps more so."[14] Thus, both Leonardo and Duchamp expand the meaning of pictorial representation by exploring how it interfaces with science, with notational devices in the form of mechanical instructions and poetic constructions (lists of word associations, anagrams, and puns).

A rapid glance at Leonardo's Codex Trivulzianus reveals the deliberate mixture of verbal and visual information, so that a "whole diagram may be a play on words."[15] This is also reflected in Leonardo's writing style in

which his characters, written in reverse with the left hand, "cannot be deciphered by anyone who does not know the trick of reading them in a mirror."[16] By mediating the legibility of writing through mirrors, Leonardo inscribes the eye into written script. In doing so he awakens the viewer to the figurative aspects of writing, to its technical and conceptual dimensions. The presence of extensive word lists, compiled according to a logic of free association that veers from poetic usage to ordinary puns, documents Leonardo's obsession with language as a mechanism for the production of signification. These lists attest to Leonardo's ambition to technologize metaphor, since language, like vision, becomes an object of fascination, a game of mirror images.[17]

Despite his exhaustive investigations of language, Leonardo nonetheless maintains that painting, because of its visual character, may have an advantage over poetry. In his "Comparison of the Arts" Leonardo parodies the Renaissance distinction between the arts, which stipulates that painting is "mute poetry," while poetry is a "speaking picture":

If you call painting "dumb poetry," then the painter may say of the poet that his art is "blind painting." Consider then which is the more grievous affliction, to be blind or to be dumb! . . . And if the poet serves the understanding by way of the ear, the painter does so by the eye which is the nobler sense.[18]

Leonardo's comparison leads him to affirm the power of painting (dumb poetry) over poetry (blind painting), since he considers visual forms to be more universal than language, whose conventions vary with different cultures.[19] This defense of the visual power of painting, based on its ability to reproduce forms through exact images, is pursued by Leonardo, who tries to save painting from its association with manual work: "You have set painting among the mechanical arts!"[20] Leonardo suggests that both painting and writing, as modes of reproduction, share the same mechanical device—the hand: the instrument of the imagination (painting) and the handiwork of the mind (writing). Leonardo's faith in the visual image, as a universal language whose posterity is guaranteed, is challenged by Duchamp, who finds both the silence of the painter and the intervention of the hand unbearable, if not outdated. Duchamp reverses Leonardo's

dictum by abandoning painting because it is "dumb." Moreover, he redefines art in poetic terms, as "ideatic" rather than "retinal"—a possible pun on Leonardo's definition of poetry as "blind painting."

Duchamp's extensive quotations and allusions to Leonardo's paintings and his notebooks have obscured other possible sources of inspiration for his work. Duchamp's interest in verbal and visual puns, and specifically, his treatment of ready-mades as "three-dimensional puns," leads us to inquire whether there are other influences that are informing his work. Duchamp's sculpture-morte, which is an assemblage of marzipan vegetables and insects in the shape of a head, suggests Duchamp's indebtedness to the works of Giuseppe Arcimboldo.[21] Duchamp's appeal to an intellectual interpretation of art evokes the Mannerist understanding of concept as conceit (concetto );—that is, both as wit and as abstract schema.[22] The incongruous, witty, and monstrous character of Arcimboldo's paintings of Composed Heads captured the attention of the Surrealists as well. In these paintings elements of pictorial still life, such as flowers, vegetables, kitchen utensils, and cooked foods, are assembled in order to generate monstrous portraits. These allegorical portraits represent seasons, elements

Fig. 31.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, spring, 1573. Oil on canvas,

29 2/3 x 25 in. Musee du Louvre, Paris.

Courtesy of Giraudon/Art Resource, New York.

Fig. 32.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, spring, 1572. Oil on canvas,

29 8/10 x 22 1/5 in. Private collection, Bergamo.

Courtesy of Art Resource, New York.

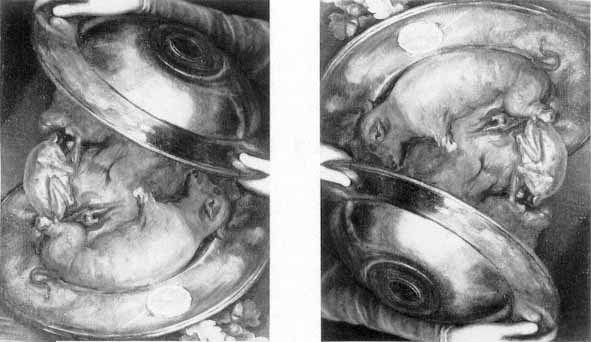

Fig. 33.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, water, 1566. Oil on limewood, 26 1/10 x 20 1/5 in. Kunsthistorisches

Museum, Vienna. Courtesy of Art Resource, New York.

(such as air, fire, or water), or types of individuals (such as the cook or the gardener), by compiling both literal and metaphorical objects associated with each particular subject.

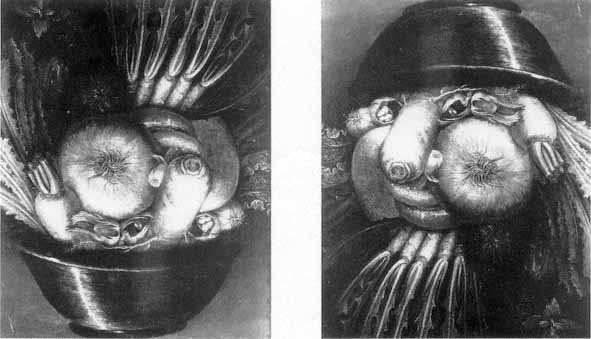

Spring (1573) (fig. 31) is a portrait composed of a variety of flowers with individual features that delineate the visible outlines of a woman's face, while another flower portrait, also entitled Spring (1572.) (fig. 32), suggests the features of a young man. These reversibly gendered images of Spring may be taken as a playful pun on its regenerative nature, and as a reflection of the hermaphroditic nature of flowers.[23] Such images underline the fact that the same material components—the flowers—may engender different figurative effects. The portrait of Water (1566) (fig. 33), which is both a physical and alchemical element, is presented through the grotesque assemblage of a dizzying variety of coiling fish, crustaceans, corals, and shells piled madly on each other—an assemblage suggesting the elemental, pagan, even primitive portrait of an alien being (a primeval sea goddess, or perhaps, an inhabitant of the New World). Initially The Cook (circa 1570) (fig. 34) and The Vegetable Gardener (circa 1590) (fig. 35) are represented respectively as a platter of cooked meats or a still life of vegetables in a bowl. On rotation, however, these images reveal the humorous semblance of the cook and the gardener, coded into the punlike reversibility of the meat platter or vegetable bowl.

These images encode into the visible a double register of perception: they are legible not only as the contents of a cooked plate or a bowl of vegetables but also as human heads. As Roland Barthes observes:

The identity of the two objects does not depend on the simultaneity of perception, but on the rotation of the image, presented as reversible. The reading turns around with no cogs to arrest it; only the title acts to contain it and makes the picture the portrait of a cook, since one infers metonymically from the plate to the man for whom it is a professional utensil.[24]

The rotation of the image reveals the fact that meaning is kinetic, since it is mechanically generated through the reversibility of the image. The perceptual unity of the image is fractured by a process of double legibility, suggesting its affinity to linguistic puns. This intellectual dimension of

Fig. 34.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, The Cook, circa 1570. Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 16 in. Private collection, Stockholm.

Courtesy of Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York.

Arcimboldo's paintings, the fact that they function on two levels at once, leads Barthes to conclude that these works function as a "terrifying denial of pictorial language."[25] While appearing to rely on pictorial traditions, Arcimboldo is violating the perceptual identity of the image by encoding within it several meanings at once. These images are visual puns highlighting the constructed and thus conceptual dimension of the visible. They reveal the fact that visual meaning is no more immediate or direct than linguistic puns, which unhinge meaning through the interplay of literal and figurative associations.

If Arcimboldo's work represents a denial of painting as a purely visual idiom, its intellectual impact can best be summarized in linguistic, poetic, and rhetorical terms. As Barthes concludes:

His painting has a linguistic foundation, his imagination is poetic in the proper sense of the word: it does not create signs, it combines them, permutes them, deflects them—exactly what a craftsman of language does.[26]

According to Barthes, Arcimboldo's talent lies in his poetic and rhetorical abilities—his exploration of similes, metaphors, and other figures of speech transmuted magically into objects. His painting represents a fascination with language and its rhetorical figures, so that the canvas becomes a veritable "laboratory of tropes."[27] Thus, Arcimboldo's paintings embody a marvelous reflection on the conceptual power of language, "the fact that in language there could be transferences of meaning (metaboles), and that these metaboles could be coded and to that extent classified and named."[28] Rather than enumerating exhaustively Arcimboldo's use of rhetorical figures, it suffices to note that his works present a theory of painting that is deliberately allegorical, to the extent that it designates itself as a system both of encoding and of decoding. Painting emerges in this context as a rhetorical gesture of deploying elements of pictorial still life in order to bring them to life again in the manner of lifelike portraits. Arcimboldo invokes the conventions of the still-life genre through the depiction of fruits and vegetables, only to divert these conventions into the service of portraiture. Rather than representing

Fig. 35.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, The Vegetable Gardener, circa 1590. Oil on wood, 13 3/5 x 9 2/5 in. Museo Civico

Ala Ponzone, Cremona. Courtesy of Scala/Art Resource, New York.

nature mimetically, he represents pictorial language as a "ready-made," that is, as a set of preestablished conventions. These pictorial conventions function like linguistic meaning: they are open to figurative interpretations, and consequently, to diverse rhetorical manipulations.

Instead of focusing on unifying forms, Arcimboldo's portraits draw our attention to the process of composition, to the fact that each element, whether flower, vegetable, or animal, retains its distinct (if muffled) existence. The composition of the image wavers and threatens to lapse at any moment into decomposition, thereby undermining its signatory role as the trademark of artistic creativity. This mutability, scripted into the image, is present at every level: it is a hinge structuring the relationship between individual details, as well as the reversibility or rotation of the image as an assemblage of diverse elements. The creative gesture implied in the composition of the visual image reveals its affinity to both poetry and humor, for composition signifies assembling elements already established by previous traditions, organizing them in a manner that both recalls and expands their original intent. Originality in this context becomes rhetorical, since it no longer signifies starting anew. Instead,the recovery of elements of pictorial still life in the service of portraiture leads to their reassemblage according to the logic of their literal and figurative potential.

Having briefly outlined Arcimboldo's contribution to painting, as a craftsman and poet of language, it is time to investigate his potential influence on Duchamp's putative abandonment of painting. Arcimboldo's recodification of the visual image in technical and mechanical terms may have influenced Duchamp's own manipulations of both images and objects. As this study will show, rotation, reversibility, and hinges are key devices to Duchamp's elaboration of the ready-mades, as linguistic and visual puns. The presence of these devices in Arcimboldo's works, which contributed to their status as "curiosities," makes visible a technical and mechanical dimension within pictorial traditions that predate the rise of industrialization. Even before Duchamp makes his own "discovery" of the idea of "ready-mades," Arcimboldo's paintings attest to the possible redefinition of painting as a rhetorical operation, which enacts the confluence and interplay of literal and figurative meaning. Duchamp's technical interest in rotation, reversibility, and hinges, all of which structure the production of visual and verbal meaning, leads him to explore puns as

conceptual machines. By actively staging the interplay of language and image, puns emerge not merely as humorous devices but as theoretical constructs expanding the notion of pictorial representation through linguistic analogues.

The discovery of the strategic role of puns enables Duchamp to abandon painting proper by providing a conceptual basis for art, understood as a medium that reassembles already given elements, and thus as a medium for reproduction rather than creativity, as it is understood in the conventional sense. Duchamp expands Arcimboldo's compositional strategies by recognizing the rhetorical character not only of pictorial representation but also of other forms of artistic representation. Arcimboldo's innovation thus does not rely on the creation of a new pictorial language but rather on the rhetorical deployment of its conventions as linguistic and visual givens. By understanding the conventions of painting as "intellectual ready-mades," Duchamp uncovers within artistic production a technical, "mechanical" dimension. In question is how the ready-made as a conceptual intervention and as a critical gesture literalizes the conventions of pictorial representation, only to expend their meaning through the redundancyof puns. Duchamp's ready-mades make possible a new interpretation of the notion of artistic production as a continued dialogue with the tradition, one which invites the spectator to complete the picture, as it were.