The River Continuum Concept

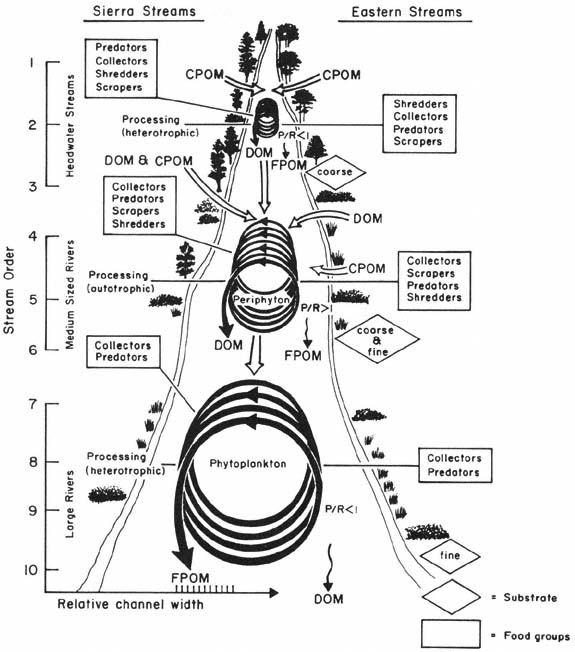

The structure and function of aquatic communities along a river system have recently been organized into the River Continuum Concept (Cummins 1975; Vannote etal . 1980). This concept involves several stream factors—temperature, substrate, water velocity, stream morphology, and energy inputs from allochthonous and autochthonous sources—which interact to influence the availability of food for stream animals. These factors should vary in a predictable fashion from headwaters to downstream locations, and should produce predictable distributions of the four feeding groups along the continuum (fig. 2).

Since headwater streams (orders 1-3) are often heavily shaded and receive large amounts of organic matter from riparian vegetation, these streams are heterotrophic. Their ratio of gross photosynthesis (P) to respiration (R) will be less than one. Coarse substrates predominate, since stream gradients and erosive power are high. Shredders reach maximum abundance in these upper stream sections because of the abundant CPOM. FPOM and DOM are used and exported downstream. Because many Sierra headwater streams originate within coniferous forests, they may differ from typical headwater streams originating within deciduous forests of the eastern United States in detrital input and lighting conditions.

Organic matter input and shading are less important in medium-sized rivers (orders 4-6) because of the greater widths and more open canopy. Increased primary production shifts these streams from heterotrophy into autotrophy, and a P:R ratio greater than one. Increased algal production allows scrapers to be abundant. Collectors are also common, and a few shredders are still present. FPOM and DOM are again used and exported downstream.

Figure 2.

The relationship between stream size and the progressive shift in structural and functional

components of streams. Box graphs of feeding groups are provided to compare Sierra streams

with eastern streams. The relative number of organisms in each feeding group is indicated

by rank-ordered lists, from large to small (from Cummins 1975; Vannote et al . 1980).

Riparian vegetation has little direct influence on large rivers (orders > 6) since the wide channels are open to sunlight, and the input of terrestrial detritus relative to water volume is small. However, FPOM from upstream sources is very important, and for this reason collectors are the predominant aquatic organisms of large rivers. Although these rivers are open to sunlight, increased turbidity restricts both light penetration and primary production by algae on the fine river substrates. Instead, phytoplankton may be important primary producers in the upper water layers, although turbidity may restrict the depth of their production. Therefore, large rivers are thought to be heterotrophic and have a P:R ratio less than one.

Shredders and scrapers are essentially absent because their food resource and coarse substrate are lacking.

Streams on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada typically pass through several plant communities—subalpine forests (conifers), red fir forests, mixed conifer forests, oak woodlands, chaparral, and grasslands—each of which contributes different organic matter inputs and shading effects. In addition, alpine tundra, montane meadows, and montane chaparral may be locally important. It is not known if all aspects of the river continuum concept apply to Sierra streams.

It is possible to summarize predictions of the river continuum concept (Vannote etal . 1980), especially as they are thought to be true for many streams in forested regions. Exceptions are known to occur for desert streams (Minshall 1978), and possibly for western montane streams (Wiggins and Mackay 1978). Some of these predictions have recently been tested in four Oregon streams, and shown to support the river continuum concept (Naiman and Sedell 1980; Hawkins and Sedell 1981).

Width, depth, and discharge increase as stream order increases. Substrate size changes from coarse to fine going from headwaters to large rivers. Diel changes in water temperature increase to a maximum in medium stream orders (3–5), then decrease downstream.

CPOM and riparian vegetation shading decrease in importance downstream, and FPOM increases in importance. This causes the CPOM:FPOM ratio to decrease as stream order increases. The particle size of detritus decreases downstream.

DOM diversity decreases downstream as labile components are used by microorganisms, causing refractory components to accumulate.

P:R ratio < 1 for stream orders 1–3—heterotropic condition.

P:R ratio > 1 for stream orders 4–6—autotrophic condition.

P:R ratio < 1 for stream orders > 6—heterotrophic condition.

Shredders decrease downstream as CPOM becomes less abundant.

Collectors increase downstream as FPOM becomes more important.

Scrapers increase to a maximum abundance in medium-sized rivers (orders 4–6) as the canopy opens and admits light to the substrate, but then decrease in larger rivers (orders > 6) because turbid water shades algae on the stream substrate.

Predators maintain approximately constant abundance along the continuum.

Biotic diversity is low in the headwaters, increases to a maximum in medium stream orders (3–5), and decreases in larger rivers.