16.2—

Isolation and Culture of Protoplasts

16.2.1—

Preparation of Protoplasts

Protoplasts may be produced, under aseptic conditions, from a wide range of plant species either directly from the whole plant, or indirectly from in vitro cultured tissues. There are two basic approaches for the enzymatic isolation of protoplasts: (a) the treatment of a plant tissue with a mixture of pectinase and cellulase so as simultaneously to macerate, or separate, cells and degrade their walls (Power & Cocking, 1970); and (b) the sequential (two-step) method involving the production of isolated cells which in turn are converted into protoplasts by a cellulase treatment (Nagata & Takebe, 1970).

Since removal of the cell wall results in loss of wall pressure upon the cell, protoplasts are isolated and maintained in hypertonic plasmolytica provided by a balanced inorganic salt medium or monosaccharide sugar solution. Mannitol,

Figure 16.1

Generally applicable scheme for the isolation, washing and counting of leaf mesophyll

protoplasts. Protoplasts isolated from callus or cell suspensions are handled in the same way.

for example, is not readily transported across the plasmalemma and therefore provides a stable osmotic environment for the protoplast.

The enzymes used for the isolation of protoplasts are crude extracts of fungal origin. The pectinases are rich in polygalacturonidase activity whilst the cellulases contain hemicellulase, b -1,4-glucanase, chitinase, lipase, nucleases and pectinase.

A generally applicable scheme for protoplast production, using the mixed enzyme procedure, is shown in Fig. 16.1. In order for the enzymes to gain access to the plant tissues, as in the case of leaf palisade and mesophyll cells, the lower epidermis must be removed by peeling or partial digestion with cutinase. Certain types of leaves, particularly of the cereals, must be sliced prior to enzyme incubation, since the epidermis cannot readily be removed. Most plant tissues and organs (roots, root nodules, coleoptile, leaf epidermis, petals, germinating pollen grains, fruit placenta, tetrads and microsporocytes) will yield protoplasts after suitable adjustment of the enzyme mixture and plasmolyticum. For example, the pollen tetrad wall consists of callose and so only an enzyme rich in b -1, 3-glucanase (snail digestive juice enzyme) will liberate protoplasts.

Protoplasts are produced from calluses and cell suspensions (Fig. 16.2b) (Wallin & Eriksson, 1973) often only during the log phase in their growth cycles, since the composition of the primary cell wall varies as secondary products, such as lignin, are deposited as the culture matures, rendering it unsusceptible to complete degradation by cellulase. In general, the production of protoplasts from an untried source will always involve a consideration of enzyme purity, pectinase to cellulase ratios, protoplast yield and viability.

Following enzyme incubation, the spherical protoplasts (Fig. 16.2a, 16.2d) must be separated from cellular debris, subprotoplasts and vacuoles. Subprotoplasts are formed during early plasmolysis when the protoplast splits into two or more subunits, some of which will be enucleate and hence non-viable. Separation can readily be achieved in a variety of ways: repeated resuspension and centrifugation of protoplasts in a washing medium; flotation of protoplasts on a hypertonic sucrose solution (Fig. 16.1); passage of the incubation mixture through a nylon sieve of suitable pore size which allows only protoplasts to pass through; or by the use of a two-phase system, such as dextran-PEG (polyethylene

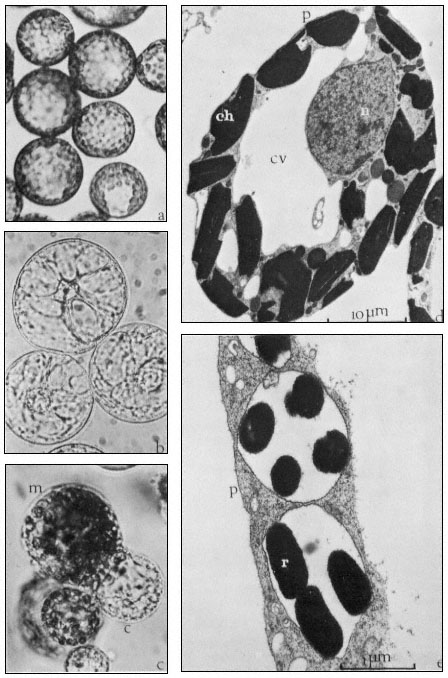

Figure 16.2

(a) Freshly isolated mesophyll protoplasts (40 µm diam.) in liquid medium

(Petunia hybrida). (b) Protoplasts (60 µm diam.) released from cultured cells. The

centrally positioned nucleus is surrounded by cytoplasmic strands ( Parthenocissus

tricuspidata). (c) Sodium nitrate induced fusion between a mesophyll (m) protoplast,

containing chloroplasts, and a colourless (c) protoplast isolated from a cell suspension.

Plastids are seen entering the cytoplasm of the colourless protoplast. (d) Electron micrograph

of a freshly isolated mesophyll protoplast (n = nucleus; ch = chloroplast; cv = central vacuole;

p = plasmalemma). (e) Uptake of Rhizobium (r) into vesicle within the cytoplasm of a protoplast

(p = plasmalemma). (Electron micrographs provided by Dr. M.R. Davey.)

Figure 16.3

Plating of protoplasts (whole plant or cultured cell origin) in agar solidified

nutrient medium. Whole plant regeneration from protoplasts takes approximately five months.

glycol), which is based upon a density difference between protoplasts and cells (Kanai & Edwards, 1973).

Freeze etched protoplasts, collected after washing and examined in the electron microscope or treated with fluorescent brighteners which specifically bind to cellulose, reveal the complete absence of cellulose fibres on the plasmalemma surface.

16.2.2—

Cell Wall and Whole Plant Regeneration

Protoplasts are cultured in either liquid or agar solidified nutrient media (Fig. 16.3). The culture media are very similar in composition to those required for the in vitro culture of cells, but with the addition of an osmotic stabilizer to prevent bursting. During culture, up to 90% of protoplasts isolated from highly differentiated cells undergo a rapid and immediate process of dedifferentiation whilst at the same time initiating the synthesis of a new cell wall.

Early stages of wall synthesis are preceded by extensive infoldings of the plasmalemma together with an accumulation of pectin-like substances in vesicles found in the peripheral layer of cytoplasm. These early stages of wall synthesis, detected after 18 hours, are unaffected by the presence, in the culture medium, of protein synthesis inhibitors, suggesting that synthesis of new RNA or protein is not required for wall initiation and that residual protein and endogenous hormone levels are sufficient. Structurally, the first formed envelope is amorphous and consists of pectins, but after a few days a second inner layer of cellulose fibrils is progressively laid down on the protoplast surface, eventually producing a near normal cellulose matrix after four or five days (Burgess & Fleming, 1974).

Nuclear division and cytokinesis is concomitant with cell wall formation. Occasionally cytokinesis does not occur, perhaps due to the presence of an incomplete cell wall, and gives rise to binucleate cells which may not be capable of further division.

Most protoplasts, like suspension cultured cells, have an optimum plating density as regards their division potential. At this density (usually 5 × 104 – 1 × 105 protoplasts/ml –1 ), the plating efficiency, defined as a percentage of the original plated protoplasts that produce cell colonies after 28 days culture, can reach 70%. As division proceeds, the plasmolyticum level in the culture medium is reduced stepwise by the transfer of agar blocks, containing the dividing protoplasts, to the surface of a similar medium of lower osmotic pressure. Individual cell colonies are pricked out, 4–6 weeks after plating, and subcultured onto a regeneration medium. Callus masses thus produced may undergo differentiation, via organogenesis, eventually producing plantlets. Regenerating protoplasts of certain species, such as carrot, will form embryoids in liquid culture.

Whole plant regeneration from protoplasts can be achieved for an expanding list of species of distinct taxonomic groups including the Solanaceae (tobacco, Petunia ) (Frearson et al., 1973), Brassicaeeae (rape) (Kartha et al., 1974),

Papilionaceae (pea, cowpea) and Scrophulariaceae (Antirrhinum ). Whole plant regeneration is not restricted to monocotyledons or dicotyledons, haploid or diploid plants, or to protoplasts obtained directly from whole plant tissues. The majority of plants regenerated from protoplasts are normal and exhibit a high degree of fertility, but a small and variable (less than 0.1%) number of plants show morphological abnormalities owing to aneuploidy and polyploidy.

An example of this can be seen following the regeneration of plants from mesophyll protoplasts of diploid Petunia, homozygous for blue flower colour. Some regenerated plants have a tetraploid chromosome number, which is also accompanied by a flower colour change from blue to red. Since well established protoplast cultures have high plating efficiencies, and hence efficient cloning potentials, abnormal plants can arise from the expression of cell aberrations present in the tissue prior to protoplast isolation.

The nutritional and hormonal requirements of cultured protoplasts are constantly varying depending upon the stage in the regeneration process. The photosynthetic capacity and respiration rate of the protoplast is suppressed by the plasmolysing conditions. Changes in metabolic requirements during the early stages of growth could be attributed to enzyme uptake during isolation and the rigours of cell wall synthesis. These subtle changes are highlighted in the crown gall (tumour) (Scowcroft et al., 1973), where protoplasts require an exogenous growth regulator supply for the initiation of division, unlike the tumour cells which are autotrophic for auxin. Following cell wall regeneration and division, the requirement for exogenous growth regulator supply is lost, suggesting that growth regulator autonomy is, at least in part, dependent upon the presence of a functional cell wall.