At the Königsberg Academy

As might be expected in a provincial capital as remote as Königsberg, the artistic milieu was undistinguished. The municipal painting gallery featured copies after Italian and Netherlandish masters from the fourteenth through the seventeenth century, on loan from the royal painting gallery in Berlin, and a small group of German, Flemish, and Dutch works—including paintings attributed to Holbein, Brouwer, and Frans Hals—that had been left to the city by a former mayor, Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel.[12] The gallery's contemporary art reflected the taste and discretion of members of the Königsberg Artists' Association. Since 1833 this organization had sponsored the biennial exhibitions at the Königsberg Castle and was responsible for acquiring modern paintings for the gallery's permanent collection. The works purchased over the years were mostly history and genre paintings, including pictures by Paul Delaroche, Ary Scheffer, Karl von Piloty, and Franz von Defregger. Since the 1870s the municipal gallery had been housed in the art academy, and the collection served as a convenient supplement to studio instruction.

The academy itself was founded in 1842 by order of King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, replacing a drawing school that had been in operation since 1790, superintended by the academy in Berlin.[13] The teaching program of this drawing school was based on that of the private Parisian ateliers: students began by copying engravings and reproductions of drawings and then proceeded to drawing, first from plaster casts and, finally, from the live model. Anatomy, geometry, and perspective were also taught. This was still the curriculum (augmented only by instruction in painting) when Corinth attended.

Unfortunately, the full extent of Corinth's activity during his years at the Königsberg Academy cannot be known because he destroyed so many of his early works. "Nobody thinks of buying these crazy products of a young man, or . . . of accepting them as gifts," he wrote in 1917 in a letter to Alexander Koch, the editor of Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration .[14] Thus no drawings or paintings of the nude model from this time have come to light. And there is little

additional evidence of what may be called student work in the strict sense of the term, since all of Corinth's paintings and most of the drawings that have survived from this time originated outside the classroom. They indicate at best that Corinth was a serious student who applied himself diligently and soon developed a keen power of observation.

Corinth's memoirs, similarly dominated by accounts of extracurricular activities, reveal nothing of his attitude toward the teaching program at the academy. He later remembered his years there as the happiest of his youth, largely because he discovered then the joys of a harmonious home life and found friends who knew how to surmount his habitual reserve. "No student was considered competent," he wrote, "unless he was also a notorious drinker. We soon developed great mastery in the consumption of alcohol. . . . All my new friends drank . . . until we could no longer tell which one of us could hold the most."[15] While at the academy Corinth set a pattern of social behavior he would follow in his early adult life.

Relations among the teachers at the academy were less congenial than those among the students. Because the school lacked effective leadership, petty rivalries among the faculty developed into bitter intrigues. The academy's first director, the history painter Ludwig Rosenfelder, had retired in 1874 after more than thirty years of service, and Max Schmidt, a landscape painter who had previously taught at the Weimar Academy, was temporarily entrusted with administering the school. For six long years, however, the Prussian Ministry of Education was unable to decide on a permanent successor to Rosenfelder. Meanwhile, the various faculty members hoping to be appointed to the vacant post regarded one another with suspicion.

Corinth's first teacher at the academy was Robert Trossin (1820–1896), a pedantic copper engraver well known for meticulously reproducing paintings by Van Dyck, Guido Reni, and Murillo as well as several contemporary masters. He taught the antiquated method of drawing after model books by Bernard Romain-Julien, the French painter and lithographer, and lithographs by Josef Kriehuber, the Viennese portraitist. Corinth remembered Trossin as patient and tenacious:

"Not too pitchy!" That was his favorite expression whenever a student had used too much black chalk. Trossin was a member of the old guard, . . . it was said that he could even boast of having been awarded a Russian medal. He had engraved Guido Reni's Mater dolorosa , and legend had it that copying the figure's neck alone had taken many months of hard work.[16]

Figure 2

Lovis Corinth, Carousing Lansquenets , 1876.

Pen, 18.4 × 24.1 cm. Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg (1957/224).

Johannes Heydeck (1835–1910), one of Rosenfelder's former students, taught drawing after plaster casts and the live model as well as painting. Like his teacher, Heydeck specialized in history paintings in the manner of Louis Gallait and Edouard de Bièfve, Antwerp painters whose works were first shown in Germany in 1842 to unprecedented acclaim. Corinth was enthralled by the extravagant staging and rhetoric of such compositions and by the care lavished on the smallest detail. He particularly admired Rosenfelder's chef d'oeuvre in the Königsberg municipal painting gallery, The Surrender of Marienburg Castle to the Mercenary Captains of the Teutonic Order in 1457 (1857; present whereabouts unknown): "Suits of armor, flowing robes, velvet draperies, and the way the Grand Master holds the key to the fortress in his veined hand. . . . these were my motifs around 1876."[17]

Carousing Lansquenets (Fig. 2), a pen-and-ink drawing, testifies to Corinth's early enthusiasm for historical subjects. Although the date and signature were added much later, the drawing was apparently done soon after Corinth began his studies at the academy. The faulty anatomy of the figures indicates

Figure 3

Otto Edmund Günther, The Gambler , 1872.

Oil on canvas, 40.8 × 48.0 cm.

Kunstsammlungen zu Weimar.

a lack of experience in life drawing; the hatchings and crosshatchings, painstakingly applied, are a legacy, no doubt, of Trossin's copying method.

Corinth's plans to become a history painter in the tradition of Rosenfelder were short-lived, however, for his interest was soon given a new direction by Otto Edmund Günther (1838–1884), a graduate of the academies of Düsseldorf and Weimar who joined the Königsberg faculty in 1876. Günther's early works include a number of historical compositions, but he had long since turned to genre painting, deriving his subject matter almost exclusively from the everyday life of Thuringian peasants. He was especially fond of themes that allowed him to explore anecdotal byplay and frequently applied the melodramatic rhetoric of history painting to such situations as the one he depicted in The Gambler (Fig. 3). In this painting a young peasant woman has come with her infant to the inn to fetch her husband, who has just lost at cards. The conception and general composition of the painting recall works by Ludwig Knaus and Benjamin Vautier, Düsseldorf artists who practiced a similar ethnographic genre. Although Günther's tonal palette differs from the lively colorism of Knaus and Vautier, the meticulous still-life elements in the picture are yet another legacy of the Düsseldorf school.

In Königsberg, Günther was originally appointed to teach painting, but he soon assumed responsibility for some of the advanced drawing classes as well. He was the youngest member of the faculty, and his approach differed markedly from that of his colleagues. Seeking to expand the experience of his students beyond the confines of the academy's curriculum, he founded a junior artists' association, where they could work independently, exchange ideas, and engage in mutual criticism. He also encouraged them to work as much as possible out-of-doors and to heighten their visual perception in a familiar milieu by choosing subjects in the Königsberg market and the harbor. Corinth's memoirs include a vivid account of the mornings he spent in the slaughterhouse by the river Pregel. There he sketched and painted, oblivious to the pushing and shoving of the butchers and the sounds of the animals collapsing beneath cracking axes, his eyes fixed firmly on the movements of the men and on the colors: the reds and fatty whites of raw meat and the purple, shot through with glistening mother-of-pearl, of the entrails hanging in clusters from iron posts.[18] Günther's informal teaching method and easy-going manner appealed to Corinth: "For me Günther was an excellent teacher. Even more important, he was like a fatherly friend. Clever and sparkling with wit, he drew me, the awkward and suspicious youth, close to him."[19]

Not surprisingly, Günther had a profound effect on Corinth's early development, both directly and indirectly. In the summer of 1876 he persuaded Corinth and several other students to travel to Thuringia, where he introduced them to some of the leading painters of the Weimar school, including the aged Friedrich Preller, who in his youth had enjoyed the support of Goethe. A visit to the studio of the landscape painter Karl Buchholz, a quiet, introspective man, impressed Corinth, who called him "the genius of that Weimar period." Corinth remembered seeing in Buchholz's studio many of the small pictures contemporary critics had praised as depictions of nature "in her morning gown."[20] Buchholz's landscapes of the 1870s are indeed poetic, though faithful, descriptions of the Thuringian countryside, their basic structure unvarying. The artist rarely, and then only sparingly, introduced human figures into his landscapes, although he usually implied human presence with a pictorial space that seems to adjoin the viewer's own. One of the landscape drawings Corinth made during his journey through Thuringia (Fig. 4) is similar in conception and evidently bears more than an accidental resemblance to Buchholz's quiet pictures. Technically the drawing is superior to the contemporary figure composition in Hamburg (see Fig. 2). Corinth's attention to the details of the half-timbered houses is matched by his care in observing the boulders in the foreground and the masonry of the bridge. The bridge leads

Figure 4

Lovis Corinth, In Thuringia , 1876. Pencil,

26 × 36 cm. Private Collection.

Photo courtesy Bernd Schultz.

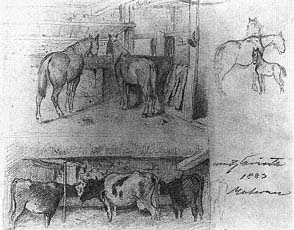

Figure 5

Lovis Corinth, The Barn , 1879. Pencil, 19.5 × 27.3 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.,

Rosenwald Collection (B-19562).

Figure 6

Lovis Corinth, Kitchen Interior , 1880. Pencil, 27.0 × 31.7 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.,

Rosenwald Collection (B-19567).

toward a compositional center that is reinforced by the shadow under the roof at the left and the repeated diagonal roof lines on the right. The careful execution suggests that the drawing may have been intended for one of the academy-sponsored competitions usually held at Christmas time, when outstanding portrait and figure studies and landscape drawings were selected for special awards.

Other works from Corinth's early student years are more specifically indebted to Günther's example. It did not take much persuasion to make the budding artist seek his inspiration in the East Prussian countryside, familiar as he was with the life and customs of the local peasants. He drew two barn interiors (Fig. 5), one occupied by horses, the other by cows, during a visit to his aunt and uncle's farm in Moterau in 1879. The signature and the incorrect date of 1883 are later additions; the lower half of the drawing was in fact a study for a small painting of a cow barn (B.-C. 2) dated 1879. Kitchen Interior (Fig. 6), drawn the following year when Corinth was back in Moterau painting portraits of his uncle and aunt (B.-C. 5, 6), like The Barn , lacks spontaneity. The awkwardly diffident style of both drawings typifies this stage in Corinth's development. The individual objects and forms are cautiously circumscribed by reinforced contours; hatching and crosshatching indicate modeling. Delicate modulations, partly exploring the grainy texture of the paper, unify the composition, whose pervasive tonality resembles that of Günther's

Figure 7

Lovis Corinth, Seated Peasant and

Other Sketches , 1877. Pencil, 26.1 × 20.0 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington,

D.C., Rosenwald Collection (B-19571).

dusky interiors. The drawing of a seated peasant (Fig. 7), dated June 26, 1877, more specifically suggests the figures that inhabit Günther's genre paintings. Here the fastidious drawing method is evident in the repeated sketches of the hands and in the portrait sketch in the upper center of the sheet, where the textures of hat, face, and shirt collar are all carefully distinguished.

The same attention to detail is found in the few paintings that survive from Corinth's years at the Königsberg Academy. They consist of a forest interior (B.-C. 1) conceived in the manner of Buchholz, the Cow Barn (B.-C. 2) already mentioned, and four portraits, including the ones he painted of his uncle and aunt in Moterau—all from the last two years at the academy. The small painting in Hamburg of an unidentified man (Fig. 8) exemplifies these early studies in oil. The averted gaze and inanimate expression indicate that Corinth grasped the sitter's image primarily in its characteristic form and appearance; the extreme close-up view allowed him to explore physiognomic details fully. The modeling is smooth and reveals a thorough understanding of the interaction of facial muscles and bone structure.

Figure 8

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of a Man , 1879. Oil on canvas on panel,

39.5 × 31.0 cm, B.-C. 3. HamburgerKunsthalle, Hamburg (2630).

Photo: Ralph Kleinhempel.

Corinth's studies in Königsberg ended abruptly in the spring of 1880 when Günther resigned from the academy. From the beginning Günther's popularity had irritated his colleagues, and as his following continued to grow, they accused him of catering to the school's best students to gain the coveted position of academy director. Rather than endure such strife, he decided to return to the Weimar Academy, but not without assuring his devoted students of the best possible further training. Some followed him to Weimar; others went to Berlin. Corinth, on Günther's recommendation, was admitted to the studio of the celebrated Franz von Defregger at the academy in Munich.