Homes Before Electrical Modernization

Riverside's utility department inventoried electrical devices in the city's 4,338 electrified homes in 1921–1923. Thesurvey gives a detailed picture of homes before electrical modernization. The average Riverside home had only fifteen lightbulbs in 1921–1923, close to California's and the nation's averages. These bulbs undoubtedly drew fifty watts of electricity or less, in line with national averages. National surveys by the electrical industry in the years 1923–1924 found that the average home had 21.7 lightbulbs. In California, the average residence in a "substantial town" had 15.9 bulbs. Before modernization, the number of light-bulbs in a home indicated the number of rooms. Research on Hamilton, Ontario, has shown conclusively that the number of rooms reflected the value of the home and the income of the household. Through this connection, the number of lights indexed the socioeconomic ranking of the home. The neighborhoods of Riverside's racial poor had the fewest lights, and the Country Club homes of the commercial-civic elite shone brightly from their hilltops. (See pl. 4.) In Casa Blanca, no dwelling had more than eighteen lightbulbs, and nearly half had no more than six. In Old East Side, 93 percent of dwellings had fewer than eighteen lightbulbs and over 29 percent of homes had no more than six. In Country Club, 62 percent of homes had more than thirty-two lightbulbs. (See table 3.4.)[14]

Besides the electric iron, owned by 82 percent of electrified households, only a minor kitchen appliance, such as the toaster or waffle iron, appeared in more than 22 percent of homes. In other words, only one in five households had an iron plus another appliance. Only one in five dwellings had the vacuum cleaner and just one in ten had the electric washing machine. Casa Blanca's seventy households did not own a single vacuum cleaner or washing machine. In Old East Side, only a little better off, a few African-American homes sampled the new labor-saving technology. In the 403 dwellings in Old East Side in 1922

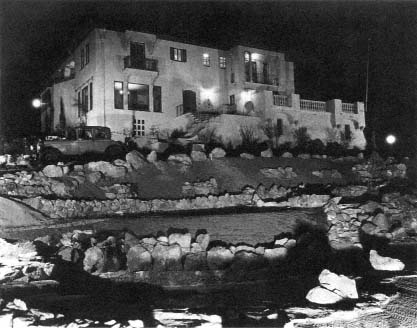

Plate 4.

The 1920s: The Homes of the Elite Shone Brightly from Their Hilltops.

([Photographer unknown.] "Hammond Residence at Night, Victoria Hill,

Riverside, California, c. 1928/1929." Riverside Municipal Museum.)

(many of which white families occupied, since only about a hundred African-American families lived in Riverside at this time), the city's appliance inventory reported twenty-three vacuum cleaners and thirty washing machines. African-American families must have owned some of these machines. In his Riverside personals column for the California Eagle , southern California's African-American newspaper, Reverend H. H. Williamson reported in December 1922 that Julian H. L. Williamson (presumably his son) had "accepted the Agnew Agency of the following electrical goods[:] Royal, Premier and Eureka Vacuum Cleaners. Electric Washing Machine and other electrical supplies." For African-American families who could not afford to buy the new appliances, Julian Williamson "has bought two standard Vacuum Cleaners which he has for rent. The Vacuum does more good than all carpeting [carpet beating] in the world."[15] We do not know how Julian Williamson's business fared. We can imagine sales in the Old East Side's minority communities were not great. Few African-American homes or Hispanic households consumed enough electricity in the 1920s to have used electric appliances.

Until their first leap in electricity consumption in 1928, when the average upper- and middle-class household adopted the plug-in radio, Riverside's homes

used little electricity. The meager increase in average consumption from 1921 to 1927 implies that few appliances were added after the 1921–1923 inventory. During the drought of 1923–1924, when civic leaders appealed for a reduction in electricity consumption, average usage actually dropped. Except for the mansions of Country Club, all homes in all neighborhoods used close to the same amount of electricity monthly, from 15.9 kwh/mo. in poor Casa Blanca to 19.3 kwh/mo. in upper-class Wood Streets. That white middle-class homes used little more electricity than the city's humblest households starkly reveals the absence of electrical appliances. The mansions of Country Club stood aside from this pattern, consuming an average of 30.8 kwh/mo. (See table 3.5.) Differences in dwelling size accounted for differences in electrical usage, even for Country Club homes. At decade's end, over half of the city's households possessed only lights and a flatiron.[16] (See table 3.6 for the fall appliance inventory.)

Introduction of the electric refrigerator did not significantly change usage. In the years 1926–1930, only 4 percent of Riverside's households had an electric refrigerator. (See chapter 6, table 6.5 for related data.) Fourteen percent of the households of professionals, citrus farmers, and business proprietors adopted the refrigerator, the only significant adoption for any class of homes in the 1920s. In Riverside, these occupational groups constituted the city's bourgeoisie and comprised 21.5 percent of all households. They are the only group in which a majority owned the houses they lived in. They constituted the restricted market for electric appliances—the "20 percent" identified by Electrical World —that the private power utilities targeted in the 1920s.[17]

The low level of electrical consumption before 1928 means that households had not electrically modernized, but it does not indicate what other domestic technologies they had or whether these technologies were modern or antiquated. Most Riverside homes installed gas cooking technology after the turn of the century and gas heating technology in the decade of the First World War. In 1910, there were 1,970 gas meters installed in the city (and 2,706 electric light meters), for both residential and business use of gas. Judging from the timing of ads for gas furnaces, Riversiders did not widely use gas for house heating until the decade of the First World War. Until then, they used oil stoves for cooking and oil and coal furnaces for central heating. Wood stoves remained common in 1900, and oil furnaces were common through the 1920s. Gas furnaces significantly improved the quality of life, because coal was dirty to handle and there were frequent complaints about smoke. In 1920, there were 3,747 gas meters in the city. Since there were 4,338 dwellings with lights in 1921, we may assume that about 85 percent of them had piped gas. Homes without piped gas were probably isolated in the citrus groves and minority neighborhoods.[18]

Although households used gas for cooking, this does not mean that they cooked with modernized technology. In the 1930s, most installed gas stoves were so antiquated that modern electrical ranges took a significant share of the home cooking market for the first time. In 1930, most gas ranges did not have oven heat controls; baking was a risky culinary adventure. Most first-generation gas

ranges also lacked insulation, which would have made Riverside's kitchens unbearable in the region's hot summers. Urging Riversiders to buy major electric appliances, a 1935 advertisement by the City Light Department recited a litany of miseries associated with first-generation gas ranges: "Electricity can be safely used by automatic appliances such as a range, water heater or refrigerator over a long period of time. There is no need to clean or adjust burners and there is no pilot light to blow out. The heat in an electric oven does not warm the kitchen in the summer and there are no fumes in winter when the house is closed up tight." In summary, by the First World War, most Riverside families had equipped their homes with illuminating, heating, and cooking technologies developed by the 1880s and widely adopted in the nation's cities by the end of the century. Except for poorer households and labor camps, Riversiders enjoyed the basic utilities Victorians believed necessary for domestic comfort. Yet the average home almost certainly did not have the latest models of these technologies.[19]