Photodocumentation of Vegetation and Landform Change on a Riparian Site, 1880–1980

Dog Island, Red Bluff, California[1]

Stephen A. Laymon[2]

Abstract.—This study used ground and aerial photos taken over the past 100 years to trace the development of the present riparian vegetation. The photos show the changes in the Sacramento River channel which have led to the present configuration of the area. Principles illustrated by these photos are: 1) the dynamic nature of the riparian system showing rapid and dramatic changes at this site; 2) the rapidity with which riparian vegetation develops; and 3) the use of historic and present day photography to document changes in a riparian environment.

Introduction

During the course of my 5-year study at Dog Island, Tehama County, I became interested in the development of the present day landforms and riparian vegetation at this site. I was able to follow up on this interest in connection with a job as archivist at the Tehama County Library and in a physical geography seminar at California State University, Chico.

Little or no work has been done to document changes at riparian sites. This study was undertaken to show the changes at this particular site, but more importantly to show the potential resources available to document land use, landforms, and vegetation pattern changes, and to show the dynamic nature of the riparian system. The use of ground photos to compare past with present conditions is a common practice in forest and rangeland situations. Problems were encountered in this study when an attempt was made to apply this technique to a flat Sacramento Valley site with tall riparian vegetation.

Methods

Research Techniques

Early ground photos were obtained from the collection of the Tehama County Library and several longtime local residents. Attempts to rephotograph these views of the study area met with limited success since the vegetation had grown so much in the ensuing 100 years, blocking the view from most angles.

The aerial photos were obtained from the United States Soil Conservation Service, US Army Corps of Engineers, and the California Department of Water Resources. Overlay projection using a photographic enlarger was used to document boundary changes.

Study Area

Dog Island, or Walton's Pasture, as it was known in the early days, has long been a favorite picnic spot for the people of Red Bluff. Now a small island in the Sacramento River, the site's amenities included an area of still water, where the land sloped gently to the river, in contrast to the high, steep bluff for which the city is named. Here the city had its waterworks, which originally consisted of a horse and wagon delivering water door to door. Later, the city pumped water directly from the river, and still later from deep wells.[3] Here also, local youths spent their days cutting school classes, and in the early days this is where most of the local people learned to swim.

In the mid-1960's the area was donated to the city of Red Bluff by the Samuel Ayers family for use as a city park and natural area. The city has kept development at a fairly low level, with a footbridge to the island, a parking lot

[1] Paper presented at the California Riparian Systems Conference. [University of California, Davis, September 17–19, 1981].

[2] Stephen A. Laymon is a Graduate Student in the Department of Forestry and Resource Management, University of California, Berkeley.

[3] Walton, T. 1956. Tehama County centennial oral history interview. Tehama County Library oral history tape.

with landscaping, two restrooms, and trails. One loop road which was put in on the mainland portion has since been closed to vehicles due to a high level of vandalism.

The origin of the name Dog Island remains a mystery since long time residents say that the area was always called Walton's Pasture, and that the dairy cattle from Walton's Dairy on the bluff to the south grazed there. One story has it that an old man ran a kennel on the island in the 1880's, but since no island existed at that time, this is impossible. A more plausible explanation is that park officials asked some local truants what they called the area and "Dog Island" was the answer.

Landforms and Topography

The Dog Island study area consists of the river, the island, the channel around the island, the mainland plain, the red bluff, Brewery Creek, and the gently sloping area from the parking lot to the footbridge (see fig. 1). The entire study area has a remarkably narrow elevation range, with 95% lying between 77.1 m. and 79.2 m. above sea level. On the northwest side, the red bluff known as Duncan Hill rises almost vertically to a height of 97.5 m., or 20.4 m. above the river level. The parking lot at the west edge of the area is between 82.3 and 85.3 m. elevation. From there the land slopes in two terraces to the side channel 76 m. away. The highest point on the island is not more than 3 m. above the gross pool level of the Red Bluff diversion dam.

Figure l.

Map of Dog Island study area and environs.

Despite having such a narrow elevation range, the area is not level, having many channels which have waterflow during flood stage. The three most prominent are old river channels that have been silted in over the years. One of these lies east of the bluff near the north boundary of the park, and was the 1850 river channel. Another lies near the east end of the footbridge. The third is found on the southeast side of the island, and was the main river channel prior to the 1937 flood.

The Sacramento River at Dog Island ranges from 170 m. to 250 m. in width. As a result of the diversion dam below Red Bluff, it is kept at a constant 77.1 m. above sea level. This is 2.4 m. higher than the river level would be without the influence of the dam. The water level is lowered slightly to 76.5 m. in the winter when no water is being diverted for irrigation. During flood stage the waters at times rise to 81 m. covering the entire area except the bluff and the parking lot. The river channel that separates the island from the mainland ranges in width from 20 m. to 41 m.

Brewery Creek is an intermittent stream which flows into the study area from the west. It was named for the brewery which was located along it near here in the 1880's. The creek has two main branches, the longer of which is 4.8 km. in length. It drains 8–10 km2 of highly eroded impermeable soils. During heavy local rains the runoff is great and the creek runs high, carrying with it heavy bedloads of rock, gravel, and soil. This is building up a delta in the side channel which may in the future connect the island to the mainland. The creek has cut a deep channel on the north side of the parking lot, and is responsible for the gently sloping gap between the red bluffs of Duncan Hill to the north and the city to the south.

Soils

Soil is the base for the vegetation of any area. Ninety percent of the soils in the study area are fertile loams, so the dense vegetation found here is not surprising.

Five types of soils are found on or near Dog Island. The island itself is an alluvial soil known as Red Bluff loam. It consists of up to 15% gravel, and has both high available water and high moisture-holding capacity (USDA Soil Conservation Service 1967).

The low area to the north of the island is made up of the Columbia loam complex, ranging from mixed soils of silt and gravels to fine sandy loams. These soils generally lie above all but the highest floods, are well drained, and have moderate permeability. They are brown to pale brown in color and are neutral to slightly acid. These are very fertile soils, favored for farming (ibid .).

The soil in the sloping area to the south of Brewery Creek is an Arbuckle gravelly loam. It

is an easily channeled soil with poor waterholding characteristics, very slow permeability, and a clay substrate (ibid .).

Duncan Hill, the bluff on the northwest side, is made up primarily of Newville gravelly loam. This soil is yellowish-brown on the surface and is slightly acidic. The subsoil is a reddish-brown gravelly clay. It is made up of sediment from conglomerate and silt stone of the Tehama formation. In addition, a portion of the hill consists of a mixture of Corning-Redding gravelly loams, a medium acidic, reddish-brown soil with a red clay subsoil. This soil has low permeability and high runoff (ibid .).

Vegetation

The vegetation-types that are found in the study area are floodplain riparian woodland, blue oak woodland, cattail marsh, and landscape plantings. Of the aforementioned vegetation-types, the latter three are the least important since they form such a small portion of the total area. The blue oak woodland found on the hill north of Brewery Creek covers only 1% of the land area. Scattered blue oaks (Quercusdouglasii ) form the canopy here, reaching up to 10 m. There is no understory, and the shrub layer consists of scattered buckbrush (Ceanothuscuneatus ). The groundcover primarily consists of introduced grasses.

The landscape plantings are found around the main parking lot, restrooms and waterworks facilities. They consist mainly of several introduced cedars and pines, a border of live oaks (Quercus sp.) along the highway, several pyracantha (Pyracantha coccinea ) hedges, scattered introduced flowering shrubs, and approximately 0.25 ha. of lawn. These are planted around several native blue oaks.

The two marsh areas are the most important of the minor vegetation-types. They cover about 1% of the area. The marsh on the southern part of the island has a thick growth of cattail (Typha sp.) with a border of willows (Salix spp.). The water is up to 0.3 m. in depth at this spot. The open areas of water are thick with small aquatic plants such as duckweed (Azollafiliculoides ). The land area around the pond that is not covered with cattail and willows is grown up with dense stands of grasses. The marsh on the mainland is just north of the mouth of Brewery Creek. It is higher than river level and only contains water after a flood or heavy rain. The cattail here is much more scattered and intergrown with grasses, herbs, shrubs, and willows, a pattern that has accelerated over the past seven years.

The primary vegetation-type in the study area is riparian woodland. Various forms of this plant community cover 95% of the land. It is an exceptional vegetation-type in the arid West. The riparian vegetation in the study area is quite diverse. Various species of trees are dominant on different portions of the area, often forming stands of clumps or bands of a single species. The western border of the island, facing the slough, is primarily old-growth cottonwood (Populusfremontii ) reaching 40 m. in height, with scattered willows (fig. 2). An understory of box elder (Acernegundo ), willows, black walnut (Juglanshindsii ), and elderberry (Sambucusmexicana ), and bands of shrubcover and groundcover layers of wild blackberry (Rubusursinus and R . vitifolius ), and the introduced Himalayan blackberry (R . discolor ) are found. The central part of the northern third of the island is the most open. It has a cottonwood canopy with a scattered understory of box elder, valley oak (Quercuslobata ), blue oak, and buckeye (Aesculuscalifornica ), and a groundcover of mugwort (Artemisiadouglasiana ) sometimes reaching 2.5 m. The northern tip of the island is a white alder (Alnus rhombifolia ) and willow thicket with no groundcover, surrounded by a blackberry thicket. The northeastern side of the island also has a cottonwood canopy with an understory of box elder, willow, and elderberry, and a shrub and groundcover of blackberry and herbaceous growth. The border of vegetation closest to the water is a dense mixture of white alder, Oregon ash (Fraxinuslatifolia ), and willows. Further south this band of alders and willows widens to about 30 m.

Cottonwoods are absent from the southeast quarter of the island. This area has a very dense canopy of alder, box elder, and willow reaching to 15 m. The trees are closely spaced, allowing very little light penetration. Groundcover is lacking in the thickly forested areas, but bands of blackberry and herbaceous growth are found in the more open spots. One alder thicket of almost 0.75 ha. is especially interesting; the trees have grown to 18 m. and many are now dying. There is no groundcover, but an understory of sycamores (Platanusracemosa ) and Oregon ash is developing. At the southern tip of the island there is a willow thicket reaching 8 m. in height and 30 m. across.

The vegetation on the mainland, south of Brewery Creek, is similar to the western part of

Figure 2.

Footbridge to Dog Island showing dense vegetation

along side channel, looking north (August, 1979).

the island, with a cottonwood canopy to 40 m., a well-developed understory of box elder, alder, and willow, and a groundcover of blackberry. This type of growth also extends along the northwest side of the slough, from 50 m. north of Brewery Creek to the freeway bridge. Also found in this area, in the slightly lower and more open spots near the slough, are several dense willow thickets reaching 7 m. in height and up to 30 m. across.

Along Brewery Creek the vegetation also has a canopy of scattered cottonwoods reaching 25 m., but the understory is much less typically riparian, with live oaks, blue oaks, toyon (Heteromelesarbutifolia ) mixed with the willows, Oregon ash, and box elders. The groundcover is a mix of grasses, blackberries, and herbaceous growth.

Black walnut is the dominant tree in the area just north of Brewery Creek and along the base of the bluff. The trees are not large, reaching only 20 m., and do not form a closed canopy. This allows light penetration and the formation of a dense ground layer of blackberries with patches of willows and elderberries. Also in this area are a number of introduced species such as mulberry (Morus sp.), black locust (Robinia pseudoaccacia ), osage orange (Maclura pomerifera ), plum (Prunus sp.), fig (Ficus carica ), and pyracantha.

At the north end of the bluff the dominant tree species is valley oak. The largest of these trees reaches 35 m. in height, and some are at least 100 years old. This site has a groundcover of grasses and a scattered understory of box elder and black walnut. The valley oak area borders the field to the north for about 300 m. and merges into an area with a canopy of black walnut and cottonwoods. In this location there is also a dense osage orange thicket of about 1 ha. which is devoid of groundcover.

The center of the mainland portion is the most open of the entire study area. Until 1975 it was a large, grassy meadow with a few scattered clumps of box elder, plum trees, and two dense box elder thickets. When the park loop road was constructed, the grass in the meadow was mowed to cut down on fire danger and provide a more "park-like" atmosphere. The meadow instantly became a defacto parking lot, the gathering place for the local teenagers, which totally denuded large areas of it. Due to reduction of competition from the grasses, the box elders began to grow rapidly and now are large trees reaching 15 m. and covering a much more extensive area. The tall rye and Johnson grasses that previously covered the meadow provided a vegetation-type that is now missing. More information on this area can be found in Laymon (1983).

Results

As static as the scene appears today at this bend in the river, as little as 40 years ago the island was very different in appearance, and as recently as 100 years ago the entire study area was litte more than a sandbar, devoid of vegetation. With the use of maps, aerial photographs, ground photos, and local legend, I was able to reconstruct the development of Dog Island over the past 100 to 130 years.

Two basic types of geologic formations are found in the study area. They are the recently formed alluvial deposits of the island and low regions to the east, and the red bluffs consisting of Pleistocene and Pliocene nonmarine sedimentary deposits to the west (USDA Soil Conservation Service 1967). This hard, red soil has been an effective barrier to westward river movement for many thousands of years. One can picture the river migrating without restraint eastward across the valley many times, always to return to the west and to stop at this 23-m. bluff.

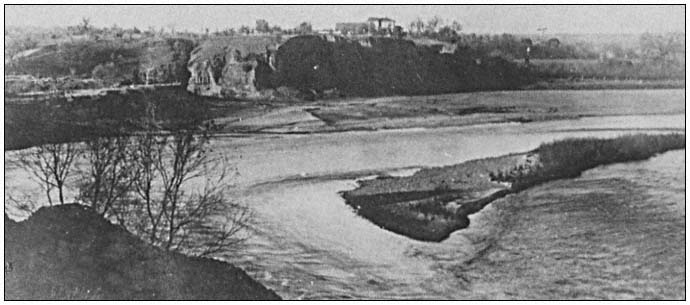

In the early 1850's when the first settlers came to Red Bluff, they found the river flowing against these bluffs from the center of the study area to 3.2 km. (2 mi.) south of town.[3] Maps from 1850 to 1900 show no evidence of even a sandbar in the river at this location. A photo taken in 1881 from the bluff adjacent to the study area looking south toward Red Bluff (fig. 3) shows a bare bluff with the river running at its base. On the right (west bank) a small delta from Brewery Creek was beginning to build up. The closest brick building on the right was the city waterworks. The building is still located at the site.

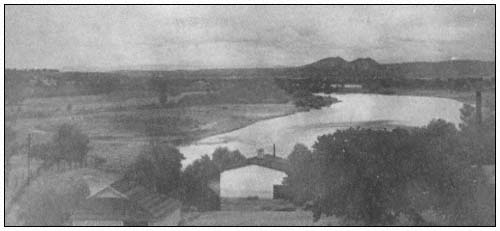

Another photo (fig. 4) taken from Red Bluff, looking north, circa 1900, shows the sides of the bluff and the rest of the study area, devoid of vegetation except for a few low willows on the sandbar in the river, a valley oak at the far right, and scattered blue oaks on top of the bluff. The amount of deposition at the foot of the bluff can be seen by comparing figures 3 and 4. Alluvial deposits had built out 30 to 50 m. in 20 years.

The next photo (fig. 5), taken in 1912, shows the area from the west, looking past the waterworks toward the Tuscan Buttes to the east. This photo illustrates the lack of vegetation and shows the river flowing towards the waterworks building (today the main flow is directed 350 m. south of that point due to deflection by Dog Island). No sandbars are seen in the river, but the west bank above the Brewery Creek outlet is in the same position as it is today. The area appears to be much lower than at present, indicating continued deposition on the mainland since the picture was taken. The first band of trees to the west of the river is very likely the 1850 river channel.

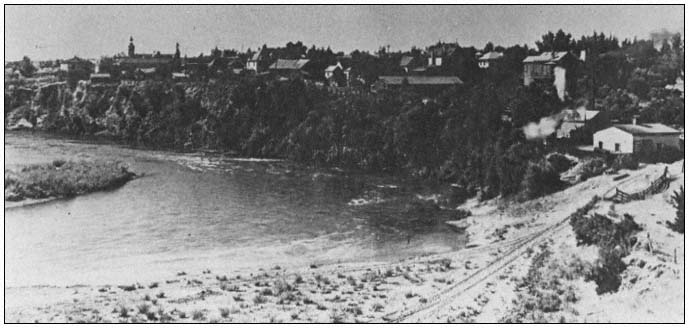

Figure 6 shows the river, looking towards Red Bluff, circa 1910, with the waterworks building on the right. One interesting feature is the amount of vegetation that has grown on the bank between 1881 and 1910.

Figure 3.

Dog Island area from bluff looking south toward Red Bluff, 1881 (courtesy of Tehama County Library collection).

Figure 4.

Dog Island from bluff at Red Bluff looking north, circa 1900 (courtesy of Tehama County Library collection).

Figure 5.

Dog Island from Garrett home looking east toward Tuscan

Buttes, 1912 (courtesy of the Wetter collection).

Figure 6.

Dog Island area from bluff looking south toward Red Bluff, 1910 (courtesy Tehama County Library).

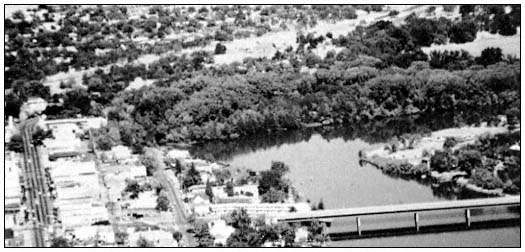

I found it impossible to rephotograph any of the four historic photos of the area. The vegetation had grown up so much that the scenes were not repeatable. An oblique aerial photo (fig. 7), taken in 1979, was an attempt to duplicate figure 4. This photo illustrates the dramatic growth of vegetation at the site. Any photo taken at the point from which the photo in figure 4 was taken would today show only the first row of cottonwoods on the south end of the island.

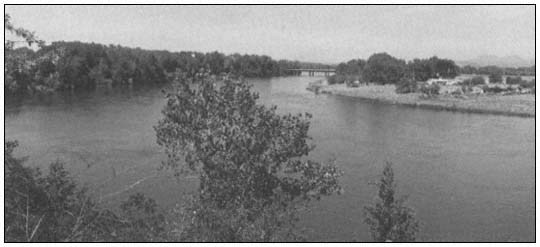

Figure 5 was taken from an upstairs balcony of the Garrett house, a 1900 Victorian, on the west side of Main Street. I was not able to attempt a photo from this spot, but did try one from the front porch. All that could be seen from this point was the live oaks along Main Street. From the balcony, possibly the first row of cottonwoods along the slough could have been seen. I was able to take figure 8 from a point on the bluff, along the river, two blocks to the south. This photo, with Tuscan Buttes in the background, again shows how strikingly the area has changed.

Figure 7.

Oblique aerial photo looking north, 1979.

Figure 8.

Dog Island area looking east from Red Bluff with Tuscan Buttes in the background, 1981.

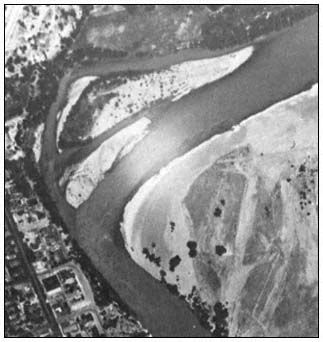

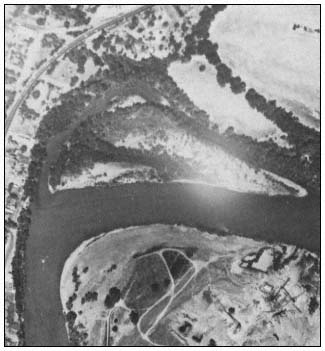

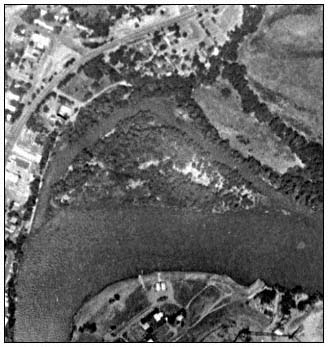

The aerial photos (fig. 9, 10, 11, and 12) were taken in 1942, 1956, 1970, and 1980. This sequence illustrates the increase in riparian vegetation at the site during the 38-year period. In 1942 only 15% of the island was covered with riparian vegetation. This had increased to 50% by 1956; to 90% by 1970; and to 100% by 1980. The mainland portion shows a similar pattern with the most dramatic increase between 1970 and 1980, when the box elders filled in the center of the mainland plain.

The first aerial photos of the Sacramento Valley were taken in 1938. I was able to study the photo of the Red Bluff area. In Figure 13 the 1938 land boundaries, the pre-1937 flood boundary, and the present boundaries are shown. From this composite map one can see the recent changes in the area. Prior to the 1937–38 flood, the land that later became the eastern portion of Dog Island was part of the mainland on the east side of the river. During the floodwaters, 65 m. of bank were carved off. The end of the peninsula was cut off, forming an island.[4] By 1952 this channel had widened to about three times the 1938 width, and the channel between it and the other island had filled in, leaving the area with its present shape.

Discussion

It is unfortunate that aerial photo coverage of the study site and the Sacramento River only go back as far as 1938. Quantitative land use changes can only be derived using these photos as a baseline. At Dog Island I was fortunate to find historic photos dating back 100 years. At most sites one would not be so lucky. Also, without the use of geographic and man-made landmarks, as I had at this site, it would be very difficult to tell where the early photos were

[4] Wetter, Judge Curtis E., Red Bluff, California. Personal communication, September, 1978.

Figure 9.

Aerial photo, Dog Island, 1942 (courtesy

of the US Army Corps of Engineers).

Figure 10.

Aerial photo, Dog Island, 1956 (courtesy

of the US Army Corps of Engineers).

Figure 11.

Aerial photo, Dog Island, 1970 (courtesy

of the US Army Corps of Engineers).

Figure 12.

Aerial photo, Dog Island, 1980 (courtesy

of the US Army Corps of Engineers).

taken. Areas where photos would be most readily available would be near towns.

The technique of rephotographing a scene to document vegetation changes on a site appears to have limited usefulness in a riparian setting of low relief. Even at Dog Island where the 20 m. bluffs were available, it was not successful since the vegetation had grown so much and views were blocked from all previously photographed angles.

Figure 13.

Geographical changes at Dog Island, 1937–1980.

Significant changes have occurred at this site and the reasons are not obvious. I believe that the deposition at Dog Island is part of the normal east-west migration of the Sacramento River. When the early settlers arrived in the late 1840's, the river had reached the red bluffs on the west. Gradually, since then, it has been moving back to the east. This process was accelerated by the 1937–38 flood which cut off the tip of the peninsula on the east side of the river. This stabilized the west side at Dog Island by deflecting the main force of the water away from the island area, such that it hit a full 1.5 blocks farther south on the red bluff. This process has slowed again since the mid-1960's when the Red Bluff diversion dam was built and some attempt was made to stabilize the banks on portions of the pool by limited use of riprap.

The increase in vegetation is a natural process as new land is being formed, but it is likely that man has accelerated the process here. The first of these factors is the construction of Shasta Dam. This dam controls the level of flow on the Sacramento River throughout the year by storing the winter floodwater and releasing it for agricultural use during the summer and fall. This creates much higher flows in the summer than would normally occur and gives more free water to the riparian vegetation than would normally be available during this period of water stress.

Possibly the most significant reason for this increase in vegetation is the raised water table created by the Red Bluff diversion dam. This dam created Lake Red Bluff which is held at a constant water level throughout the growing season. This provides the vegetation with an unlimited supply of water. At no place on the area (except the bluff itself) is water a limiting factor to plant growth.

It will be interesting in the years to come to see what landform and vegetational changes take place on the island. It is doubtful, with the bank stabilization that has taken place near the area, that major changes in the shape of the site will occur. The most significant change that is now taking place is the silting in of the side channel. Riparian vegetation will be growing here within 20 years if this process continues. Young valley oaks and black walnuts are found on higher portions of the area and these species will likely become more dominant as the years pass.

When considering the study area and the riparian woodland system in general, two concepts must by held foremost in one's mind when making management decisions. The first concept is that change is the essence of the riparian zone. In 120 years, major changes have taken place here and the current vegetation structure is a product of this change. If man insists on a stagnant situation through the use of channelization, the riparian community will not survive.

The second concept is that of the rapid growth and resistance of this vegetation-type. In a period of 40 years this area has been transformed from a gravelbar to a mature cottonwood/willow riparian woodland. The successional changes are still taking place, and in another 40 years a valley oak/black walnut riparian woodland will have taken its place. The land is the important resource, and if man can refrain from plowing, grazing, or riprapping it, the forest will return in a very short time.

Literature Cited

Laymon, Stephen A. 1983. Riparian bird community structure and dynamics: Dog Island, Red Bluff, California. In : R.E. Warner and K.M. Hendrix (ed.). California Riparian Systems. [University of California, Davis, September 17–19, 1981.] University of California Press, Berkeley.

USDA Soil Conservation Service. 1967. Soil survey, Tehama County, California. U.S. Department of Agriculture.