The Mass-Mediated Epidemic:

The Politics of AIDS on the Nightly Network News

Timothy E. Cook

David C. Colby

In June 1981 a rare assortment of opportunistic diseases was first noticed among otherwise healthy gay men. Now, ten years later, the epidemic known as acquired immune deficiency syndrome is one of the leading political and social dilemmas facing the United States and the world. Privately experienced illness became not only a public phenomenon but also, as political actors slowly agreed that it demanded public response, a public problem.[1]

On public problems see Joseph R. Gusfield, The Culture of Public Problems: Drinking-Driving and the Symbolic Order (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), and John W. Kingdon, Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies (Boston: Little, Brown, 1985). Our perspective has been heavily influenced by the literature on construction of social problems; for an overview see Joseph W. Schneider, "Social Problems Theory: The Constructionist View," Annual Review of Sociology 11 (1985): 209-29.

How did this happen? We nominate one key actor: the news media. If Vietnam was the first "living-room war," with images broadcast directly into American homes, then AIDS may well be the first "living-room epidemic." As early as June 1983, when the first public opinion polls on AIDS were taken, virtually all of those surveyed were aware of it, even though scarcely 3 percent of them actually reported knowing a person with AIDS.[2]These and other data through 1986 are reported in Eleanor Singer, Theresa F. Rogers, and Mary Corcoran, "The Polls—A Report: AIDS," Public Opinion Quarterly 51 (1987): 580-95. See also James W. Dearing, "Setting the Polling Agenda for the Issue of AIDS," Public Opinion Quarterly 53 (1989): 309-29.

After all, the media help to determine which private matters, such as disease, become defined as public events, such as epidemics. Since the reach, scope, and gravity of problems cannot be fully judged in one's immediate environment, the media construct the public reality, a reality distinct from the private world that we inhabit, and provide "resources for discourse in public matters."[3]Harvey Molotch and Marilyn Lester, "News on Purposive Behavior: On the Strategic Use of Routine Events, Accidents and Scandals," American Sociological Review 39 (1974): 101-12, at p. 103.

But the process by which AIDS became an epidemic of public proportions is far from value free. Though journalists may claim to reflect outside reality, news cannot report everything that has occurred in a given day. News is invariably selective. Not all issues and individuals seeking to make news are equally favored in the process of determining

Earlier versions of this essay were presented at the annual meetings of the American Political Science Association, Chicago, September 1987, and the International Communication Association, San Francisco, May 1989. Portions of this essay appeared in the Journal of Health Policy, Politics and Law (16 [1991]) and are reprinted with permission of Duke University. We are indebted to many individuals, whom we will thank personally for advice and suggestions; but particular thanks go to Timothy Murray for his exemplary research assistance and coauthorship of the earliest version; Martha Roark for additional research assistance; Michael Kolakowski for advice and suggestions on poll data; Brenda Laribee for helping to process the charts; Williams College for several Division II grants and the University of Maryland Baltimore County for financial support; the Vanderbilt University Television News Archives for its excellent services; and Edward Brandt, Ellen Hume, Jim Lederman, and Keith Mueller for detailed critiques of earlier drafts.

newsworthiness.[4]

The most important studies of the processes of newsmaking in national media include Edward J. Epstein, News from Nowhere: Television and the News (New York: Random House, 1973); Leon V. Sigal, Reporters and Officials (Lexington, Mass.: Heath, 1973); Gaye Tuchman, Making News (New York: Free Press, 1978); and Herbert J. Gans, Deciding What's News (New York: Vintage, 1979).

Nobody really knows what news is, but journalists still have to produce a certain amount of this highly perishable commodity every day. They must develop ways to "routinize the unexpected," which push them toward recurring news sources, stories, and concerns. But, unlike most news, AIDS was unforeseen and unintentional. It thus provides unusual insight into the processes of negotiation by which events become structured as news.[5]"We take accidents to constitute a crucial resource for the empirical study of event-structuring processes" (Molotch and Lester, "News as Purposive Behavior," p. 103).

The media's identification and definition of public problems work not only on mass audiences but also on policymakers, who are highly attentive to news coverage. They are most likely to respond to highly salient issues, even those that provoke considerable conflict, but largely in the context of the initial frame that the media have provided.[6]

For a fuller discussion of the media's role in elite agenda setting, see Timothy E. Cook, Making Laws and Making News: Media Strategies in the U.S. House of Representatives (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1989), chap. 6.

The construction of AIDS as a social and political problem thus has influenced not merely our reaction as individuals but also our response as a society and a polity.Finally, though most attention has separated the scientific study of AIDS from "its metaphors,"[7]

For example, Susan Sontag's influential and thought-provoking books Illness as Metaphor (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1978) and AIDS and Its Metaphors (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1989) tend to adopt a positivist approach that separates scientific discourse from its literary versions.

the very process of science is affected by the media. Because publicity can influence the allocation of the grants, profits, and prizes that enhance physicians' and scientists' careers, they have incentives to present findings that the media will cover, a situation leading to what has been called "science by press conference."[8]Jay A. Winsten, "Science and the Media: The Boundaries of Truth," Health Affairs 4 (1985): 15. For a fuller account see Sharon M. Friedman, Sharon Dunwoody, and Carol L. Rogers, eds., Scientists and Journalists: Reporting Science as News (New York: Free Press, 1986), and Dorothy Nelkin, Selling Science: How the Press Covers Science and Technology (New York: W. H. Freeman, 1986).

Moreover, since scientific results are fundamentally products of the questions asked, the media's priorities can push medical inquiries in certain directions. Even the answers may be affected by patients' quickness to report those symptoms and behaviors that have been the subject of media coverage.In short, the media may have played (and may continue to play) a critical role in the public perception of the epidemic and the range of possible social and political responses to it. By their ability to transform occurences into news, the media exert power. After all, "one dimension of power can be construed as the ability to have one's account become the perceived reality of others. Put slightly differently, a crucial dimension of power is the ability to create public events."[9]

Harvey Molotch and Marilyn Lester, "Accidental News: The Great Oil Spill as Local Occurrence and National Event," American Journal of Sociology 81 (1975): 235-60 (quoted passage, p. 237).

We suggest that the addition of AIDS to the political agenda was slow because of the way the problem was defined and the epidemic framed. Many observers have suggested that because the group initially most affected included gay men, the media delayed reporting AIDS, consequently postponing and distorting the governmental response.[10]

See for example, Dennis Altman, AIDS in the Mind of America (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1986), pp. 16-21.

Although AIDS had entered public awareness by mid-1983, public opinion polls at that time showed relatively little concern that AIDS

would reach epidemic proportions. The issue had been seemingly contained, defined as a distant, not an immediate, threat. Only after the summer of 1985 did a large percentage of the public begin to conceive of the disease as likely to affect their world—and only then was there much pressure on the government to do something about the epidemic.[11]

In addition to the results presented by Singer et al., "The Polls—A Report: AIDS," this conclusion is based on Gallup poll data from the releases of July 7, 1983, and August 18, 1985; Newsweek, August 8, 1983, p. 33; Newsweek, August 12, 1985, p. 23; New York Times, September 12, 1985, p. B11; and the Harris poll released September 19, 1985.

Even then, political response was muted and often confused. AIDS did not become an agreed-upon issue until President Reagan and Vice-President Bush gave their first speeches on the epidemic in 1987, six years after the initial reports.Systematic studies of media coverage of AIDS have been largely limited to print media, such as newspapers and newsmagazines.[12]

The central systematic studies of news content in print media published thus far include Edward Albert, "Illness and Deviance: The Response of the Press to AIDS," and Andrea Baker, "The Portrayal of AIDS in the Media: An Analysis of Articles in the New York Times," both in The Social Dimension of AIDS: Method and Theory, ed. Douglas A. Feldman and Thomas M. Johnson (New York: Praeger, 1986), pp. 163-94; Edward Albert, "Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome: The Victim and the Press," Studies in Communications 3 (1986): 135-58; William A. Check, "Beyond the Political Model of Reporting: Nonspecific Symptoms in Media Communication about AIDS," Reviews of Infectious Diseases 9 (1987): 987-1000; and Sandra Panem, The AIDS Bureaucracy (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1988), chap. 8. On journalists covering the AIDS beat, see James Kinsella, Covering the Plague: AIDS and the American Media (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1989). The only examination to our knowledge of television news coverage of AIDS is Everett M. Rogers, James W. Dearing, and Soonbum Chang, "Media Coverage of the Issue of AIDS," a paper submitted to the Media Studies Project of the Wilson Center, Washington, D.C., 1989, but its primary concern is with the timing of stories rather than the interpretive frameworks provided therein.

Most imply that AIDS was initially ignored because it was regarded as a "gay disease"; but once the possibility of a large-scale epidemic became clear, AIDS evolved into a subject inviting metaphorical and sensationalized treatment. Dennis Altman has conjectured that "from mid-1983 on, AIDS had entered the popular consciousness and was widely discussed. Nor did press attention go away. … Medical stories are particularly attractive to the media, and where they can be linked to both high fatalities and stigmatized sexuality, we have all the ingredients for banner headlines."[13]Altman, AIDS in the Mind of America, p. 19. See also Warren Burkett, News Reporting: Science, Medicine, and High Technology (Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1986), p. 145: "The story of AIDS contained all elements necessary for sensational reporting: sex, threat to health, mystery, and high probability of death."

But print coverage was far from consistent. The volatility of the AIDS story is curious, give Edward Albert's claim that "acquired immune deficiency syndrome seemed tailor-made to the who, what, where and when ideology that often accounts for the content of stories which appear as the 'news.'"[14]Albert, "Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome," p. 136.

The opportunities for sensation, drama, and moralizing notwithstanding, AIDS presented numerous dilemmas for journalism as an institution.[15]

Kinsella, in Covering the Plague, presents numerous portraits of individual journalists and shows how their individual perspectives and experiences shaped their approach to the epidemic, but he neglects the impact of standard practices of journalism as a whole. As we shall argue here, the high points and valleys of AIDS coverage was due to more than individual journalists' attributes or failings.

First, the earliest identified group at highest risk comprised gay men. The media would have to deal with individuals who had not attained journalistic standards for newsworthiness prior to 1981. Particularly in television, reporters emphasize issues that are thought to affect the majority of their audiences. With the exception of a few event-driven stories—such as the 1975 discharge of Leonard Matlovich from the Air Force for homosexuality, the 1977 referendum organized by Anita Bryant to repeal the Dade County (Florida) gay rights ordinance, and the 1978 assassination of gay San Francisco County supervisor Harvey Milk—homosexuality and homosexuals had not become a news topic of continuing concern.[16]Ransdall Pierson, "Uptight about Gay News," Columbia Journalism Review, March-April 1982, pp. 25-33; Timothy E. Cook, "Setting the Record Straight: The Construction of Homosexuality on Television News," paper presented to the Inside/Outside conference of the Lesbian and Gay Studies Center at Yale University, New Haven, October 1989.

Reporters on the AIDS newsbeat, whether gay or straight, dealt with a group that mainstream news had neglected.Second, the subject matter of AIDs, mixing as it does references to blood, semen, sexuality, and death, defied traditional notions of "taste."

As Herbert Gans has noted, journalists take the audience into account by considering norms of taste, especially during the dinner hour of the nightly network news.[17]

Gans, Deciding What's News, pp. 242-46. He notes three other considerations for journalists seeking to protect their audience: shock, panic, and copycat behavior.

This audience is viewed as a collection of middle-class families. Av Westin, who has been an executive news producer at ABC and CBS, revealed the networks' logic: "I developed a series of questions to determine what should go into a broadcast and what should be left out. Is my world safe? Are my city and home safe? If my wife, children and loved ones are safe, then what has happened in the past twenty-four hours to shock them, amuse them or make them better off than they were? The audience wants these questions answered quickly and with just enough detail to satisfy an attention span that is being interrupted by clattering dishes, dinner conversation or the fatigue of the end of the working day."[18]Av Westin, Newswatch: How TV Decides the News (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1982), p. 62.

By making such choices, newspersons may inadvertently censor themselves; issues are thereby avoided or euphemized.Finally, and perhaps most important, the media were in the unenviable position of seeking to raise public awareness without creating public panic. While the media take seriously their perceived role of educating and alerting, reporters sense that they must also avoid being inflammatory.[19]

See, for example, David Paletz and Robert Dunn, "Press Coverage of Civil Disorders: A Case Study of Winston-Salem, 1967," Public Opinion Quarterly 33 (1969): 328-45.

The reason is simple. Because they believe that they should reflect politics rather than shape it, they are reluctant to appear to be interfering with the natural unfolding of the political process. Reporters attempt to ignore the consequences of their work lest they be in the paralyzing role of having constantly to predict the future impact of their reporting. They prefer either to avoid topics that could touch off panic or to report such topics in a reassuring way. Indeed, the media periodically examine their coverage of AIDS; and, as we shall see, the network news reports often disclose considerable discomfort as they perform the balancing act between education and instilling "AIDS hysteria."[20]For example, Don Colburn, "Pursuing the Disease of the Moment," Washington Post, February 10, 1987, Health Section, p. 7; Eleanor Randolph, "AIDS Reporters' Challenge: To Educate, Not Panic, the Public," Washington Post, June 5, 1987, p. D1.

We focus here on television news. Television is perhaps, in Tom Brokaw's curious but pungent phrase, "the most mass of the mass media." Although it is commonly reported that citizens receive the bulk of their information from television news, most Americans do not attend systematically to any single medium but, instead, assemble information in haphazard and casual ways. Television news is only one part of the news environment to which individuals react.[21]

Doris A. Graber, Processing the News (New York: Longmans, 1984); John Robinson and Mark Levy, The Main Source: Learning from Television News (Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage, 1986).

Nonetheless, it is a central part of that environment and has become important in its own right as an agenda setter. Daily newspapers have become more analytic as television takes over the role of headline services for breaking news.And public officials, although they may not often watch the network news for new information, attend to television "to find out what the rest of the nation is finding out."[22]

Michael J. Robinson and Maura Clancey, "King of the Hill," Washington Journalism Review 5, no. 6 (July-August 1983): 49.

Studying television as well as print is also crucial because the two versions often diverge and because audiences learn differently from television accounts than from newspaper stories, as recent studies of information about AIDS have confirmed.[23]

A survey in Washington, D.C., comparing television-reliant and newspaper-reliant citizens, and an experimental study in New England, estimating learning from television, magazine, and newspaper accounts, both point to significantly lower amounts of information about AIDS among television viewers. See Carolyn A. Stroman and Richard Seltzer, "Mass Media Use and Knowledge of AIDS," Journalism Quarterly 66 (1989): 881-87; and W. Russell Neuman, Marion Just, and Ann Crigler, "Knowledge, Opinion, and the News: The Calculus of Political Learning," paper prepared for delivery at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Washington, D.C., September 1988.

In each medium the process of newsmaking is essentially the same: go where news is expected to happen, consult individuals who are agreed-upon authoritative sources, and rework these recorded observations into a coherent account that takes advantage of widely shared cultural scripts and storylines. But the product differs. Television presents different kinds of information. Visual images provide more personalized, vivid, and memorable messages, which may differ from those set forth in print.All newsmaking assembles stories around a particular angle, but newspapers typically conceal this process by the inverted pyramid form, where each succeeding paragraph becomes progressively less essential, so that editors can cut at will. In television, the imperative is to keep the audience tuned in, or at least to ensure that they don't switch channels. Consequently, television news programs are thematic, attempting to flow both between and within stories. Similar subject matters are clustered together, and the half-hour moves gradually from important and serious "hard news" to more contemplative or upbeat feature stories. The reports themselves are miniature narratives, with the anchor's introduction, the correspondent's lead, and a closer that functions as the moral of the story. These stories introduce conflict that is either resolved or left hanging to bring viewers back for more the next day.

As Daniel Hallin has insightfully noted, "Because of their different audiences, then, and because of television's special need for drama, TV and the prestige press perform very different political functions. The prestige press provides information to a politically interested audience; it therefore deals with issues . Television provides not just 'headlines' … nor just entertainment, but ideological guidance and reassurance for the mass public. It therefore deals not so much with issues as with symbols that represent the basic values of the established political culture."[24]

Daniel C. Hallin, The "Uncensored War": The Media and Vietnam (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), p. 125. Emphasis in original.

Of course, the symbolic presentation favored by television news may serve either to reassure or to mobilize.[25]The best statement on symbolic presentations continues to be Murray Edelman, Politics as Symbolic Action: Mass Arousal and Quiescence (New York: Academic Press, 1971).

Which symbols and which visuals are chosen can have a considerable influence on the public construction of the epidemic.We begin our investigation of AIDS coverage with the nightly news broadcasts by the three major commercial networks. Despite the proliferation of news into the morning and nighttime hours, the nightly news remains the flagships of the three major networks, ABC, CBS, and NBC. Moreover, since 1968 these broadcasts have been videotaped, archived, and indexed by Vanderbilt University's Television News Archive. For our analysis we made a search of all AIDS news stories listed in the archive's abstracts and indexes through December 1989. We then viewed and analyzed all stories from January 1981 through April 1, 1987, when President Reagan made his first major speech about the epidemic.

The Aids "Attention Cycle"

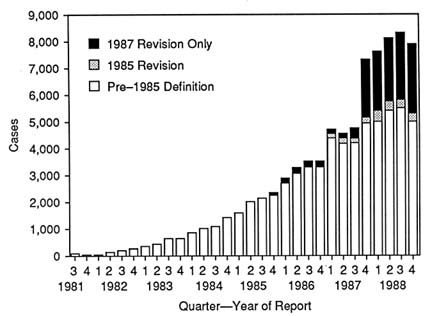

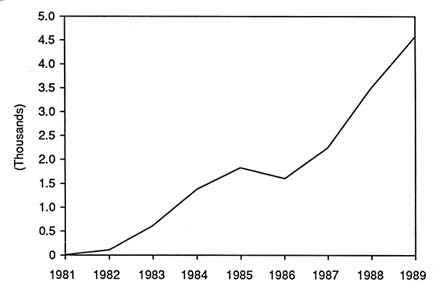

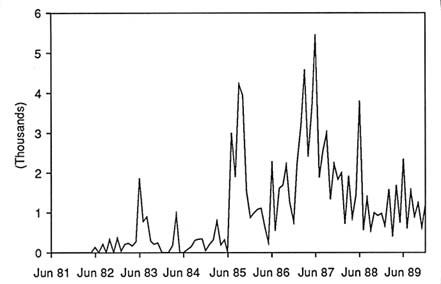

First of all, we should establish a benchmark against which to measure television coverage. In this case there is an easy comparison with empirical measures of the increasing severity of the epidemic. The medical community recognized the first cases in 1981. The number of new cases of AIDS per year, as estimated by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), rose—at first exponentially and then more gradually (see fig. 1). As for medical attention, a count of articles on AIDS and related subjects in Index Medicus shows similar growth, with a slight drop in 1986, from twenty articles on AIDS in 1981; the medical community sustained regularly increasing interest in the problem (see fig. 2). If the media were merely reflecting either a growing problem or a professional concern, the trajectory of television coverage would follow similar lines as the exponential increase in morbidity rates.

Such was not the case (see fig. 3). There were few stories on AIDS as long as it was identified as a disease that affected only gay men. The CDC had first reported evidence of the disease in June 1981, and the New England Journal of Medicine carried three original articles and an editorial on AIDS in its December 10, 1981, issue. Although major newspapers did report this news,[26]

For example, the New York Times carried stories on July 3, July 5, and August 29; the Chicago Tribune, on July 4; the Washington Post. on August 30 and December 11; the Los Angeles Times, on June 5, July 3, and December 10; and the San Francisco Chronicle, on June 6 and August 29.

there was no nightly news coverage in 1981 and only six stories in 1982. With the exception of the three initial stories about the disease that attacked gay men, the nightly news did not cover AIDS until it spread beyond groups that could be held complicitous in their own illness—gay men and ntravenous drug users.[27]The initial indications of AIDS among heterosexual intravenous drug users appeared in early 1982; the CDC first reported AIDS infections among Haitians in July 1982.

As the risk groups proliferated, the amount of news time devoted to AIDS rose in 1983 but declined in 1984 and early 1985, even as the morbidity rate dramatically rose, until Rock Hudson's trip to Paris to receive an experimental treatment against AIDS. Hudson's illness revitalized

1. AIDS Cases (by quarter of report and case definition)—United States, 1981–1988

SOURCE : Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 38, no. 14 (April 14, 1989): 230.

and legitimized the media's interest in ways we shall shortly describe, but again the attention slackened off after Hudson's death in October, only to rise to a new height in 1987 with increasing attention to the possible heterosexual transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)[28]

Although the virus was named differently at different times, we choose to call it by the terminology agreed upon in 1987.

and with Reagan's and Bush's first pronouncements on AIDS. Since that peak AIDS has become routinely reported news, with especially heavy concentration on the International AIDS Conferences that have been held generally in June.What accounts for this remarkably variable interest of network news programs in AIDS? In particular, how can we understand that their coverage actually declined at the same time that the severity of the epidemic continued to rise and as medical interest increased? One possibility is provided by Anthony Downs's famous "issue-attention cycle."[29]

Anthony Downs, "Up and Down with Ecology: The Issue-Attention Cycle," Public Interest 28 (1972): 38-50.

In the first stage of the cycle, the condition exists but is not constructed as a social problem; in the second stage an event triggers awareness of the problem and the public's demand that it be solved; in the third stage the public discovers the political and/or economic costs of solving the problem; and, finally, the revelation of these costs forces

2. Number of Medical Articles on AIDS, 1981–1989

a decline in public interest. But Downs recognized that not all problems are likely to go through a cycle, and there is no evidence that the public beginning in late 1983 saw any costs to doing something about AIDS.

Another possible explanation has to do less with the public than with institutional dynamics of journalism. In particular, while some argue that AIDS was a perfect subject for newspersons, we contend that the epidemic caused newspersons less to sensationalize than to reassure, particularly following their apparent realization that their initial reporting had touched off "an epidemic of fear." News organizations therefore decreased their attention to the disease, which was, in any event, rapidly becoming so familiar that it was "old news." Thus, beginning in late 1983, coverage was sporadic, dictated more by events than by topics. Yet the cycle could begin again if it were refreshed by dramatic new developments that synopsized the reach and extent of the epidemic—and such were the effects of the disclosure of Rock Hudson's illness in July of 1985 and later of the evidence from abroad, particularly Africa, of a heterosexual epidemic.

Phases Of The Cycle

The dynamics of the media's attention to AIDS are further revealed in the themes that characterized the coverage. From 1981 to 1985 the

3. Seconds of Nightly News Time on AIDS, June 1981–December 1989

nightly news developed, in sequence, five major clusters of themes on AIDS. The first saw AIDS as largely a gay disease, implicitly blaming gay men and their "life-styles" for the disease. This "mysterious" disease became "deadly" only when it went beyond the initial risk populations, but the media then bypassed openly gay persons with AIDS while pursuing other angles and only eventually legitimized gay spokes-persons as accepted authorities. The spread of AIDS beyond the originally demarcated risk groups was the second theme. The "epidemic of fear" about AIDS provided a third theme. The fourth sought scientific breakthroughs and potential cures that provided hope along with hype—reassurance to calm the fears resulting from the reports of the spread of the disease. The fifth theme, news about the most famous AIDS patient, Rock Hudson, provided a new legitimacy for the issue.

Although these themes do not fall into distinctly separable phases, there is a recognizable time sequence to their initial development. The gay stories appeared at the outset in 1982. They were quickly followed by the stories emphasizing the spread beyond gay men, focusing in particular on hemophiliacs, children, and recipients of blood transfusion.[30]

It is worth noting that until very recently intravenous drug users have been mentioned only in passing as a high-risk group.

In May 1983, following Dr. Anthony Fauci's speculation that HIV might be transmitted by recurring personal contact, the news began to battle the "epidemic of fear," a phase that overlapped with the search on thepart of the media to locate scientific breakthroughs. At this point attention was paid to the isolation of HIV and the development of blood-screening tests, and only occasionally to angles that diverged from the media's stereotype of an illness affecting gay men in New York and San Francisco. Interest declined until the illness of Rock Hudson, which, in effect, certified the newsworthiness of the disease and provided an opportunity for the networks to investigate other aspects of AIDS. And the cycle began anew.

The Mysterious Disease

Scientists at the National Center for Disease Control in Atlanta today released the results of a study that shows that the life-style of some male homosexuals has triggered an epidemic of a rare form of cancer.

NBC, June 17, 1982

Anchor Tom Brokaw's lead-in to Robert Bazell's report in June 1982 introduced a new topic to nightly network news audiences. Both stressed the possibility that gay men's behaviors were directly responsible for the disease. Bazell noted, "Investigators have examined the habits of homosexuals, looking for clues," and then switched to a clip of a gay man, Bobbi Campbell, saying, "I was in the fast lane at one time in terms of the way that I lived my life. And now I'm not." After soliciting a comment from another gay man, Billy Wilder, that the disease itself was worse than dying, Bazell ended on a pessimistic note: "Researchers are now studying blood and other samples from the victims, trying to learn what causes the disease. So far they have had no luck."

A similar angle characterized ABC's first report, on October 18, 1982. George Strait began with a profile of a gay man, Phil Lanzaratta, who had been hospitalized several times in the previous months and who said, "I was walking around like a time bomb." In introducing the report, anchor Max Robinson had referred simply to "a mysterious disease," and the signals that Strait gave on the gravity of the disease were also mixed. After showing graphic photographs of lesions from Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) and emphasizing that it was spreading at "an alarming rate," the worst epidemic since polio in the 1950s, he also noted that Lanzaratta's doctors thought he would likely survive. Most prominent was the link of the epidemic to gay men and then to their sexual practices. Indeed, Lanzaratta's body became a signifier for the

disease; a shot on the left half of the screen of him walking down the street—with close-cropped hair, mustache, tight-fitting jeans, and cowboy boots—was juxtaposed with the words "acquired immune deficiency syndrome" on the right. And after listing the established high-risk groups, Strait returned to the connection between sexuality and disease: "Hotlines in New York and other cities are handling up to fifty calls a day from homosexuals who fear their sexual intimacy may make them especially vulnerable to immune deficiency syndrome." Yet, although his report was more vivid than Bazell's initial report, complete with graphics of the states affected and lists of the diseases that affected individuals contracted, Strait ended with a reassuring touch, noting that medicine and government were both hard at work trying to figure out the syndrome.

The first AIDS story on CBS, by Barry Petersen on August 2, 1982, diverged in many ways from Bazell's and Strait's reports. Unlike its counterparts, CBS did not initially entrust AIDS coverage to its medical or science correspondents and consequently presented a more overtly political report. Petersen paid less attention to the life-style hypotheses circulated by epidemiologists; instead, he was the most critical of the government's slow response and treated the men who had been diagnosed with the disease as tragic figures, fighting nobly against the odds, rather than as pathetic, helpless victims. Starting with a filmed quote from, again, Bobbi Campbell about his "devastation," the report featured gay activist Larry Kramer complaining that Kaposi's sarcoma was unknown because it was a "gay cancer"; it also included sound bites from physicians such as James Curran and Marcus Conant, who noted that spending on KS could also lead to an increased understanding of cancer. The report closed, "For Bobbi Campbell, it is a race against time. How long before he and others who have this disease finally have answers, finally have the hope for a cure?" But even here, Petersen seemed to be less concerned about its initial outbreak than about its spread: "It appeared a year ago in New York's gay community, then in the gay communities of San Francisco and Los Angeles. Now it's been detected in Haitian refugees. No one knows why." He continued to list its presence among hemophiliacs and intravenous drug users, again asking why; but, tellingly, he never asked why KS appeared among gay men. Even the angriest and least judgmental of these three reports did not find the first identification of the epidemic among gay men to be a puzzle.

All three reports—by starting with the experiences of Campbell, Wilder, and Lanzaratta and then broadening out—followed the networks'

tradition of placing disaster in its human-interest context,[31]

Av Westin, in a memo to ABC News correspondents, suggested, "If we are covering a hurricane, begin by concentrating on some wind-swept birds ('the gulls knew Clara was due. They felt the wind early. ...'), then move on to the general panorama of impending disaster." Westin explained his logic as follows: "[A] viewer has to grasp the main points of a story quickly before they are embellished with supporting elements. Starting 'small' and then broadening out helps maintain clarity in the short time usually available" (Newswatch, p. 44).

but they referred to the outbreak simply as "mysterious" and "fascinating." Only later would it turn "deadly." Implicitly, these reports characterized gay men—because of their "habits" or their "sexual intimacy"—as responsible for their illness.These themes were not surprising. Much of the early speculation by scientists came from epidemiology, which studied stereotyped social behaviors thought prevalent among the initially affected group—behaviors such as the use of poppers (the drug amyl nitrite), multiple sexual partners, and the like.[32]

Gerald M. Oppenheimer, "In the Eye of the Storm: The Epidemiological Construction of AIDS," in AIDS: The Burdens of History, ed. Elizabeth Fee and Daniel Fox (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), pp. 267-300; Meyrick Horton and Peter Aggleton, "Perverts, Inverts and Experts: The Cultural Production of an AIDS Research Paradigm," in AIDS: Social Representations, Social Practices, ed. Peter Aggleton, Graham Hart, and Peter Davies (New York: Falmer Press, 1989), pp. 74-100.

Defined primarily as a venereal disease, AIDS drew on an old and familiar stigma in American culture.[33]Allan Brandt, No Magic Bullet: A Social History of Venereal Disease in the United States since 1880 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987). Horton and Aggleton, in "Perverts, Inverts and Experts," note that a blood-borne disease, such as hepatitis B, is actually a more accurate comparison for AIDS than venereal diseases such as syphilis, let alone leprosy and plague.

Even when a gay man with AIDS was interviewed in respectful terms, shot in the close-up "touching distance" favored by human-interest stories that personalize and individualize the subjects, some images stressed the "otherness" of the group. Strait's report showed two men walking to the camera's right shot from above, so that the viewer can see only their legs. As the men pass the camera, it pans up when their faces cannot be seen, while the voiceover tells us, "The only clue to this disease are the types of people caught in this epidemic." The New York location, the shots from above and the back, and the shoulder bag of one man provide a visual shorthand that would be repeated in later reports as a symbol of the anonymous, potentially dangerous urban gay man.But the most striking aspect of this first phase is how short-lived it was. In contrast to the thorough popular-magazine coverage at this time, the initial network reports on AIDS were the only stories to emphasize the "gay plague." In their next stories all three networks concentrated on the spread beyond gay men, "needle-using drug addicts," and Haitians to hemophiliacs, children, and recipients of blood transfusions. Yet the early framing did not disappear. Instead, by stating in each story that the syndrome was first seen among homosexuals—and by often accompanying such a statement with stock footage of gay-pride marches shot from above[34]

For example, ABC, December 10, 1982.

or a gay couple from the back[35]For example, ABC, March 3, 1983.

—the media reinforced the portrayal of AIDS as something emanating from the anonymous gay "other" and striking "innocent victims." And no other persons with AIDS were depicted in such an advanced state of the disease as were gay men. In its grisliest version, an NBC report on April 29, 1983, showed a skeletal man in a hospital bed lamely saying, "Dying at thirty-five isn't so bad. Maybe I'm being given a break," with the voiceover informing us that shortly after this was filmed, the man did indeed die.Many stories blamed the sick in subtle ways. The first story on the AIDS "Haitian connection" (shown on NBC, June 21, 1983) concluded that AIDS cannot be blamed on Haitians but "is transmitted among Haitians just as it is in the United States." The narration tells us that poverty, poor health practices, and prostitution are related to the transmission. But then the reporter takes the viewer via a hidden camera into a Haitian bar that caters to foreign gay men—with the implication that AIDS came to the United States from Haiti via an infected gay man who had sex with a Haitian "boy prostitute." The Haitian connection thus became subsumed under the already existing storyline of gay responsibility for the disease. The tendency to blame gay men was apparent even years later. On May 6, 1985, for example, when NBC reported on a hemophiliac who gave AIDS to his wife and child, the anchor referred to this family's plight as a "tragedy that goes beyond numbers," and noted that these people "live in a mobile home in central Pennsylvania, far from the gay bars in New York and San Francisco." The tragedy of those who live near the gay bars in those cities—for, as this report also noted, three-quarters of all persons diagnosed with AIDS were gay men—was ignored, since their disease was no longer news.

In short, gay men were shown more often as carriers than as victims. Yet at the same time, gay spokespersons were occasionally identified as authoritative sources, if only where they reacted to events initiated by others.[36]

The analysis in this section is based on the following broadcasts: (1) ABC: October 18, 1982; March 2 and June 26, 1983; October 23 and November 23, 1984; March 2, July 28, September 16, October 2, and October 21, 1985. (2) CBS: August 2, 1982; March 23, June 26, and August 6, 1983; April 23 and October 9, 1984; March 2, August 27, September 18, September 19, September 24, October 2, October 15, November 7, and December 12, 1985. (3) NBC: June 17, 1982; June 21, June 26, and October 13, 1983; March 15, August 17, and October 9, 1984; March 2, May 6, July 25, September 18, and October 2, 1985. The first network story that was clearly pegged to a media event by a gay group was CBS's coverage of an ACT UP demonstration on Wall Street on March 24, 1987.

Thus, a March 2, 1983, ABC report on proposals to exclude all gay men from giving blood quoted Virginia Apuzzo of the National Gay Task Force protesting such a move and urging that more attention be paid to research. Gay spokespersons could also be included if they participated in an official event that intersected with already established newsbeats and legitimated the networks' use of their comments. Thus, on August 1, 1983, two networks, ABC and CBS, reported on congressional hearings with numerous gay witnesses; both included Roger Lyon's quote, "I came here today to hope that my epitaph would not read that I died of red tape." In the first several years of coverage, gay men were asked to talk about discrimination; gay health issues; and, to a lesser extent, other gay problems, such as being closeted. By 1985 gay spokespersons were quoted on screen fifteen times in the network news—far less frequently than the ninety-five times that non-gay authoritative sources, such as politicians and doctors, were quoted but more often than the initially negative portrayal would have predicted.[37]Baker, "Portrayal of AIDS in the Media," finds a similar pattern in 1983 in the New York Times. We should be cautious about interpreting these figures too literally, however, since the gay movement may have sought out non-gay individuals (such as Mathilde Krim, researcher from Sloan Kettering Cancer Center) to serve as authoritative sources. The most important conclusion we can derive is that until mid-1985 the gay movement was not a salient aspect of television coverage.

How do we explain this turning to gay sources for comments in the midst of often negative reporting? One clue is provided by earlier television news coverage of homosexuality, which tended to be respectful

as long as the subject matter concerned individual gay men or (much more rarely) individual lesbians. But in the initial stages of the epidemic, when gay men were categorized as a high-risk group , the ambivalence of the media toward homosexuality as a social phenomenon became clear.[38]

See Cook, "Setting the Record Straight," for a further discussion.

Only when the individualistic emphasis could return would the media's assessment be less condemning. Second, because the gay movement was well organized and, once AIDS first hit, its members became convinced that the news media had to be pursued, reporters were provided with willing and easily accessible sources.[39]Altman, in AIDS in the Mind of America, points out that the governmental response to AIDS probably would have been even slower if AIDS had been first identified in less organized groups, such as Haitians or intravenous drug users. Social movements face difficulty in making news, not only because of reporters' doubts about their authority (and hence their newsworthiness) but also because they are often either insufficiently organized to constitute a newsbeat or are ambivalent about the priority of making news. See especially Edie N. Goldenberg, Making the Papers: The Access of Resource-Poor Groups to the Metropolitan Press (Lexington, Mass.: Heath, 1975). Presumably, the professionalization within AIDS activism—what Cindy Patton has termed the move from grass roots to business suits—has contributed to a greater willingness on the media's part to rely on sources within the gay movement. For a good study of this shift, see Donald B. Rosenthal, "Dilemmas in the Institutionalization of AIDS Service Organizations in Upstate New York," paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, San Francisco, August 1990.

These sources, of course, may have unwittingly enabled the media to frame AIDS as a largely gay disease.[40]The media attention may have been a double-edged sword for the gay movement in the early stages; even if negative, it alerted audiences both to the importance of the disease and to the presence of gay organizations. John D'Emilio, in Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983), notes that, paradoxically, even negative reporting in the 1950s and 1960s spurred the development of a gay minority by alerting audiences to the presence of a community they had not known existed before.

But at a later point, once the threat to the innocent was downplayed, gay men moved from being persons responsible for the spread of the illness to "owners" of the problem, legitimate authorities to be interviewed. As Altman has noted, the gay movement may have thereby attained legitimacy, but at a terrible price.[41]Dennis Altman, "Legitimation through Disaster: AIDS and the Gay Movement," in AIDS: The Burdens of History, ed. Fee and Fox, pp. 301-15. On owning a problem, see Gusfield, Culture of Public Problems.

The Threat To The Innocent

An unknown and mysterious disease is spreading. It has killed more people than toxic shock syndrome and legionnaires' disease combined. It first struck homosexual men; but, as Robert Bazell reports, others are getting it.

NBC, October 6, 1982

After the intermittent coverage when gay men and other minorities were deemed the sole persons with AIDS, the media dramatically reported the spread to the "general public."[42]

The analysis in this section is based on the following reports: (1) ABC: December 10, 1982; March 2, July 14, and September 7, 1983; August 16, August 29, September 5, September 11, September 19, October 21, November 13, and November 14, 1985. (2) CBS: December 10, 1982; February 26, March 23, July 26, August 30, and November 9, 1983; April 26, August 2, September 1, November 23, and November 29, 1984; July 29, July 30, July 31, August 27, September 5, September 11, September 18, November 14, December 12, and December 13, 1985. (3) NBC: October 6 and December 10, 1982; March 1, July 14, August 22, August 30, and November 2, 1983; October 9, October 10, November 9, and November 29, 1984; February 27, March 15, April 26, May 6, May 7, July 30, August 15, August 16, August 29, August 30, September 5, September 11, September 19, October 17, November 7, November 8, November 13, November 14, November 21, December 5, and December 8, 1985.

In July 1982 the CDC had noted thirty-four Haitians with opportunistic infections similar to those discovered in gay men, but the networks did not emphasize the spread until the CDC reported AIDS in hemophiliacs and infants. The December 10, 1982, reports of all three networks emphasized the spread of AIDS by blood transfusions, with two noting the CDC's recommendations that those in the high-risk groups not give blood. Two reports fed the fears about the spread. ABC ominously concluded, in an invasion-of-the-body-snatchers tone, that "blood banks cannot know who to look out for if they cannot know what to look out for." CBS suggested that the virus also might be transmitted by saliva, sperm, and mucus in addition to blood. Stories about transmission by blood continued throughout the period under study and were pushed farther forward in the broadcast, even well after the development of the blood test. Otherpotential transmission modes—such as saliva, tears, mucus, urine, dirty needles, and even close contact—were alluded to, though with lesser frequency than blood. These stories, unlike their predecessors, could have proved alarming to viewers. For one, they could easily slip from the conditional "could" to the more inevitable "would." And, among those infected, gays were shown in ways that emphasized their roles as patients or as others, whereas hemophiliacs and children were portrayed as ordinary individuals who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. The gay men interviewed in the first three reports, for instance, were shown alone, either in public places such as parks and cafes or in doctors' offices. In contrast, the hemophiliacs appeared at home surrounded by family members. The reports stressed the fact that hemophiliacs could not adjust their behavior to avoid exposure to AIDS—thereby implying that gay men could adjust their behavior.

Typical in this regard was a CBS story from February 26, 1983. Anchor Bob Schieffer began by noting, "Some doctors suspect that blood banks and plasma centers may be spreading a new and mysterious disease called AIDS." The report dealt with hemophiliacs, which the correspondent, David Dow, labeled a "small but vulnerable part of the population." The networks never reported on gay men in similar terms, though those terms would have been accurate. In the CBS report Dow interviewed one hemophiliac:

DOW :

The unaffected are beginning to worry. … For college professor Charles Bell and many other hemophilia patients, the plasma concentrate they can store at home and inject themselves is not just a lifeline; it is their key to an active, somewhat normal life.

BELL :

I really don't have an option. I really have to continue using the plasma, or the concentrate as it's called. The thought of abandoning the kind of life I have as a result of the concentrate is almost unthinkable. …

DOW :

For now, no one is flatly declaring that the nation's blood supply is in danger. Too little is known about AIDS itself—what it is and how it spreads. But until those questions are answered, other questions will persist among those Americans who depend on the blood of others for their own life and health.

The demarcation between "innocent victims" on one hand and the gay men and IV drug users on the other, which implicitly characterized early AIDS reporting on television, became explicit later on, when virology took over from epidemiology and the stress on behaviors became downplayed. On September 18, 1985, in a revealing passage during the Rock Hudson saga, CBS anchor Dan Rather introduced one sequence:

"It's not at all what people first thought—a mysterious killer that seemed to strike beyond the bounds of respectable society. People thought AIDS was something you caught in alleyways from a dirty needle or picked up in gay haunts doing things most people don't do. But now science knows it is a deadly virus that makes no moral or sexual distinctions. And it's making its way very slowly toward Main Street."

The networks could find little assurance in the statistics about the spread, with the exception of the decreases in syphilis infection rates among gay men.[43]

For example, NBC, June 13, 1983.

At the outset all that reporters could do was to draw some reassurance from their setting—usually a hospital laboratory or, as in George Strait's first report, the Capitol building. Posing in front of the Capitol, Strait closed his report with these words: "In Phoenix and in labs around the country, researchers are trying to solve the mystery around AIDS and the disease it causes. To help, Congress has just appropriated a half a million dollars for more research, reflecting the growing national concern about the spread of this immune deficiency syndrome" (ABC, October 18, 1982). In contrast to Bazell's downbeat presentation in the first report on NBC, later reports sought to depict people hard at work unraveling the mysteries of the mysterious and now "deadly" disease.The "Epidemic Of Fear"

Fighting the fear of AIDS, it seems, is as important as fighting the disease itself. … As researchers attempt to conquer this disease called AIDS, public officials attempt to conquer the epidemic of fear. … It is a delicate balancing act, raising the level of concern for the disease on the one hand, while reducing the level of panic on the other.

ABC, June 20, 1983

Anchor Max Robinson's lead-in and Ken Kashiwahara's voiceover adroitly captured the dilemma for journalists covering AIDS. Already, in noting the spread beyond gay men, they had fallen into a typical approach to a potential disaster, best indicated by a study of how newspapers covered (and how the population responded to) predictions of earthquakes after the discovery of the Palmdale bulge north of Los Angeles. News fell into "an alarm-and-reassurance pattern. … [S]tories began with dramaticized accounts of worst-possible scenarios, as though to shake readers out of their lethargy, and concluded with reassurances

about the seismic resistivity of most local construction … as though to quiet the alarm so deliberately generated."[44]

Ralph H. Turner, Joanne M. Nigg, and Denise Heller Paz, Waiting for Disaster: Earthquake Watch in California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), pp. 58-59.

As these authors note, such a pattern, derived from journalists' attempts to show two sides to an issue, could easily leave audiences confused or able to read in their own (possibly incorrect) conclusion. In television, alarm could easily dominate, even when the final tagline attempted to reassure.For newspapers AIDS became front-page news in May 1983, after Dr. Anthony Fauci's editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association noting cases of children with AIDS and raising the hypothesis that recurring household contact could be a mode of transmission. The networks did not initially rush to cover this new story. Indeed, only ABC, in a twenty-second throwaway, made any mention of it at all. However, the potential of contamination by casual contact provoked fearful responses, which, in turn, were ambiguously covered by reporters, who partially condemned the "hysteria" but also instilled fears about the potential for a pandemic.[45]

The analysis in this section is based on the following reports: (1) ABC: June 20, 1983; August 2, August 26, September 9, September 13, and September 25, 1985. (2) CBS: May 18, June 19, August 6, and August 11, 1983; March 2, August 9, August 25, August 30, September 9, September 10, September 11, September 12, September 18, September 19, October 3, and November 7, 1985. (3) NBC: May 24, June 20, July 14, September 4, and October 13, 1983; August 26, September 9, and September 12, 1985.

CBS reported the first epidemic-of-fear story on May 18, 1983. Dan Rather introduced the segment, which was placed early in the broadcast to signal its importance,[46]

This story appeared six minutes after the broadcast began; it was the first story after the first commercial break. By contrast, the three original stories appeared after twenty-two (NBC), fifteen (CBS), and fourteen (ABC) minutes.

with an overview of the exponential climb in AIDS cases. He continued: "Those of course are frightening figures, and Barry Petersen tonight reports that in some places fear of the disease is itself becoming epidemic." In the report San Francisco police officers were shown demanding special masks and gloves; health care and sanitation workers were shown, concerned about contamination; and blood banks were shown turning away donors whose "life-style fits that of AIDS victims." Yet, in his closing words, Petersen left open the possibility that such fear was warranted: "Doctors say they do not yet know how far and how fast the disease could spread."Petersen's report on fear of AIDS was perhaps the most alarming. Later reports, starting with NBC's May 24 story, explicitly attempted to calm these fears. In mid-June all three networks aired lengthy stories about "AIDS hysteria" within a day of each other. The news had piqued interest in the spread of the disease, which had gone from being "mysterious" to being "deadly." Now the attention shifted from the threat to would-be innocent bystanders caught by circumstance to social institutions. Most prominent among these institutions were, of course, blood banks and hospitals; but prisons, the military, and schools were all shown as undergoing considerable anxiety, with the possibility of infected or exposed inmates, soldiers, or schoolchildren. Such locales often provided, whether advertently or not, an opportunity to spread

misinformation as frightened individuals made emotional statements.

Take CBS's prison story from June 19, 1983. Anchor Morton Dean introduced the lengthy story by quoting Edward Brandt, assistant secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, to calm concerns with factual information about the only known modes of transmission. But the report had other effects. Reporter Joan Snyder said that AIDS was probably not spreading rapidly in prison: "But what has spread rapidly is fear." She illustrated this statement by showing an emotional correctional officer shot in dramatic close range and yelling, "Get these people out of the jails! It's gonna cost people's lives one way or another. Either we're going to die of AIDS or these people are going to kill us or something. Get 'em out of the jails! That's the answer." Snyder could not counteract this vivid quote with a bland statement from what she termed "a correctional officer at a meeting called by state prison officials to try to relieve anxiety among prison workers with medical information." Her indication of no evidence for transmission by casual contact was again counterbalanced by inmate liaison Pedro Soto arguing, "Once you have AIDS, you're gonna die. … There is no way that they can tell you how to catch AIDS. They have ideas. They're checking 'em out. But they cannot say," followed by an inmate endorsing the idea of quarantine.

These stories often showed persons-in-the-street commenting in ways that defied scientific understanding, even at that time, of how the disease would spread, or expressing doubts that one could be absolutely sure. Reporters, hewing to the strategic ritual of objectivity, never specifically rebutted these misleading statements, apparently considering it sufficient to mix alarm with reassurance from public officials.[47]

Kashiwahara's June 20, 1983, story on ABC, for example, followed images of discrimination with the statement "Politicians and health officials have declared war on AIDS hysteria," with sound bites by New York mayor Edward Koch, CDC scientist James Curran, and Health and Human Services secretary Margaret Heckler.

The report could then inadvertently reinforce and authenticate the viewers' doubts.Ironically, although journalists sided with those who were trying to calm the fear, their reports about it may have served not to exorcise but to heighten it. The emotionally charged quotes from upset individuals would in all likelihood have overriden the cool statistics proffered by the authorities. Other vivid film excerpts portrayed reactions that may have (incorrectly) seemed legitimate: police officers donning surgical gloves and masks, prison guards putting on futuristic "special protective outfits should they have to subdue a prisoner with AIDS," and television technicians refusing to fit a microphone on a person with AIDS.[48]

See ABC, June 20, 1983; CBS, June 19, 1983; NBC, June 20, 1983.

In later stories the news would recount the various impacts of fear:

discrimination against AIDS patients; discrimination and violence against gay men; shortage of blood supplies after incorrect rumors that people could contract AIDS by donating blood; anxiety among health care workers, police, and prison guards; refusals to adopt AIDS children; and, most frequently of all, the attempts to keep children with AIDS out of public schools. Only a few stories presented segments showing cool, deliberate reactions from the public: the townspeople who allowed a child with AIDS to attend school without protests; the young playmates of an HIV-positive child.[49]

ABC, September 13, 1985; CBS, January 22, 1986.

Vividness alone does not explain this preference. Witness a moving NBC story of a teacher with AIDS who had been transferred out of his classroom for the hearing-impaired and who won a suit that returned him there; his press conference in the school library was interrupted by several beaming students who embraced him (November 23, 1987). But such a story evaded the usual priority of television media for setting forth an easily reported either-or conflict, preferably in continuing sagas, such as those of schoolchildren struggling to stay in school: Ryan White in Kokomo, Indiana, in 1985; or the Ray brothers in Arcadia, Florida, in 1987. In search of the balance between being informative and being interesting, network news tended to offset the bland reassurances of government health officials with the dramatic emotions of those who feared the worst. The epidemic of fear was far from stemmed.Faced with an impossible balancing act, the news media seem to have decided to turn their attention elsewhere. As long as a story had to involve two distinct sides that often talked past each other and were rarely directly rebutted by reporters, calling attention to the potential gravity of AIDS provoked fearful responses, whose coverage simply made matters worse. The epidemic had not played itself out, but the topic as a news story had, and journalists would now await authoritive scientific and political sources to let them know when news on AIDS would happen.

The Search For The Breakthrough

There may be a dramatic breakthrough in the treatment of AIDS tonight. Maybe. Everybody is anxious for some encouraging news.

NBC, October 29, 1985

Tom Brokaw, in his lead to a story about the promising effects of Cyclosporin A, typifies reports on scientific research and treatments for

AIDS. After emphasizing the spread of this disease to "innocent" victims and the consequent fearful reaction, the networks proceeded, beginning in 1983, to express cautious hope, reassuring the audience that scientists were inexorably progressing toward a treatment, cure, or vaccine.[50]

The following broadcasts are examined in this section: (1) ABC: July 12, August 1, and October 26, 1983; April 4 and April 23, 1984; January 10, January 11, March 2, and July 26, 1985. (2) NBC: January 14, April 29, July 8, and July 12, 1983; March 15, August 17, and December 14, 1984; January 17, February 8, March 2, July 24, July 26, October 29, and November 11, 1985. (3) CBS: July 12, 1983; March 1, April 4, April 19, April 20, and April 23, 1984; January 5, January 10, February 20, March 1, March 2, May 5, May 6, May 10, July 25, September 4, September 12, September 18, November 14, and December 13, 1985.

As with newsmagazines, the focus of coverage shifted from a preoccupation with life-style and contagion to reports on science and medicine.[51]Albert, in "Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome: The Victim and the Press," notes that life-style/contagion stories in newsmagazines peaked in May-July 1983 and fell behind science/medicine stories in May-July 1984.

Such attempts to reassure had been evident in news reporting since Strait's October 1982 ABC story, but the search for a breakthrough began in earnest in mid-1983. For example, on April 29, 1983, NBC reported that the isolation of a virus was the "best lead yet" and, three months later (on July 12, 1983), that research on Interleukin-2 provided "encouraging news tonight—not enough to call it a breakthrough, but encouraging news nonetheless."This phase differed from the preceding ones. Coverage was no longer topic-driven, whereby enterprising reporters dug up new aspects of a continuing story. Instead, it was event-driven; that is, reporters routinely awaited event summaries or pseudo-events, such as news conferences or demonstrations, to discuss the otherwise less than newsworthy subject.[52]

For discussion of these issues, see G. Ray Funkhouser, "The Issues of the Sixties: An Exploratory Study of the Dynamics of Public Opinion," Public Opinion Quarterly 37 (1973): 62-75. This split is similar to the contrast between enterprise and routine journalism provided by Sigal, in Reporters and Officials.

Reporters consequently became even more dependent on authoritative sources, such as political officials, prestigious doctors, or drug companies' spokespersons, to create such events and allow an opportunity to cover the issue. In the absence of new developments announced by these sources, the only news about AIDS that would develop were occasional odd angles, such as the death of a great-grandmother from AIDS (NBC, February 27, 1985).Such authoritative sources also had reason to look for a breakthrough and to provide reassurance. At the very least, governmental officials and scientists were more likely to call a press conference when progress and promising news would occur.[53]

A recent example occurred in 1989, when HHS secretary Louis Sullivan appeared before the news media to announce the government's finding that the drug AZT worked to slow the reproduction of HIV among infected asymptomatic individuals. According to Sullivan's spokesman, had the news not been so upbeat, his boss would likely not have appeared (Robert Schmermund, comments in panel "NIH Announces AZT," at the Harvard School of Public Health, April 1990).

Moreover, the Reagan administration was eager to limit the damage near an election year. Thus, in a July 12, 1983, story on Interleukin-2, NBC quoted Health and Human Services secretary Margaret Heckler: "It's the first glimmer of light. It's not the whole answer, but it is promising." The most notable example of the media's being misled was Heckler's prediction that, with the isolation of the virus, a vaccine was only a few years away. The reporters added some caution, but the optimism of the authoritative source dominated the reports. Meanwhile, scientists downplayed dead ends and stressed advances—findings that the news media would cover and that would boost the scientists' credibility and their careers. Given the interest on the part of both political officials and scientists to callattention only to progress, if not breakthroughs, much reporting on AIDS went from alarming to soothing.

To be sure, many reports on cures were often interwoven with stark data on the spread of the disease. In an August 17, 1984, report on the isolation of the virus by San Francisco scientists, NBC introduced the story with the following statement: "No one knows for sure what causes AIDS. But what both scientists and researchers know is that it attacks homosexuals mostly and that invariably it kills. Tonight Robert Bazell tells of one more step in the search for clues to the disease and a new and sinister element in the AIDS equation." As with many of the stories, NBC first alarmed and then assured the audience—by raising anxieties that can be resolved. Thus, the media created a "strong" science story that reaches the "boundaries of truth."[54]

Winsten, "Science and the Media", pp. 11, 9.

Sometimes they offered only faint hope, but virtually no reports were as downbeat as Bazell's original story in 1982. On March 1, 1984, in one of its several reports on simian AIDS, CBS interviewed a researcher who described his findings as follows: "There is no immediate significance, in terms of therapy. However, there is great significance in terms of hope." Most stories carried caveats, such as "Officials warn against premature expectations of a quick cure"; "Scientists caution that even when they are certain of the cause of AIDS, it will probably take years of more research before they develop a vaccine"; and "The next step: a vaccine. But that's a big step, and researchers say that it could take years."[55]

Respectively, NBC, July 12, 1983; NBC, March 15, 1984; CBS, April 20, 1984.

This tendency from mid-1983 until mid-1985 is important because dead ends in research were not considered newsworthy by any of the actors involved in making news—neither the sources (whether politicians or physicians) nor the journalists—even though gay spokespersons were then vocal in their denunciation of government inaction. And even more than most sources, the networks stretched to the boundary of truth, looking for a breakthrough that would reassure. Reports on tongue sores, a plant fungus, feline AIDS, and experimental drug treatments provide examples.

This attempt to be the first to report a breakthrough is, of course, common to many science stories, as the flap over "cold fusion" in 1989 clearly illustrates. But not only does this penchant exaggerate preliminary or mixed results; it also leads to omissions, so that certain stories (or parts of stories) are not covered.[56]

In the story of Baby Jane Doe, an infant with multiple birth defects, the major distortion, according to Klaidman and Beauchamp, was not inaccuracies but incomplete reporting. See Stephen Klaidman and Tom L. Beauchamp, "Baby Jane Doe in the Media," Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 11 (1986): 271-84.

Breakthroughs are key, because if events are not perceived to move the process along, then by definition news did not occur.[57]Mark Fishman, in Manufacturing the News (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1980), has suggested that reporters at a governmental newsbeat decide what to cover by referring to a "phase structure," or an idealized version of how that institution's process unfolds; newsworthy points occur when the process moves from one phase to the next. The same may be true of science correspondents, but here the idealized process may well be science marching on.

We have already noted that television failed toreport the AIDS story until more than a year after the disease was first noted. And when it did cover the AIDS story, it overlooked a number of significant events: the development of a clinical case definition of AIDS in September 1982; the voluntary guidelines developed by the American Red Cross and others advising against accepting blood from high-risk groups in January 1983;[58]

NBC briefly mentioned this, but ABC and CBS did not.

the discovery in May 1983 by scientists from Harvard, the Pasteur Institute, and NIH that HIV infected at least some AIDS patients; Interleukin-2 clinical testing that began in March 1984; the First International Conference on AIDS in Atlanta in April 1985; and the May 1985 NIH study showing that health care workers have a low risk of contracting HIV.The event-driven storyline not only tended to discourage access of gay spokespersons to the media, who could not point out the lack of progress that they perceived; it also meant that the story of how the gay community was responding to the crisis went almost unreported. From mid-1983 to mid-1985, most events concerning AIDS were not included in the news, and larger assessments of the epidemic and the responses to it were all but nonexistent. In this event-driven phase of routine journalism, the news media may have continued intermittently to sound the alarm, but the alarm was now at least equally balanced by reassurance. Consequently, AIDS stories not only declined in number but also became less urgent and tended to imply that the situation, however grave, was largely under control.

Rock Hudson And The Legitimation Of Aids

Hudson's condition has brought AIDS back into the headlines, but after all it is an ongoing emergency.

NBC, July 24, 1985

The illness and death of a famous actor with a masculine image, "the most well-known victim yet" (CBS, July 25, 1985), legitimized the media's attention to this disease as a continuing story instead of sporadic breaking news. Indeed, it would not be too far-fetched to describe AIDS coverage in television as falling into two phases: before and after Rock Hudson. Some of this new attention can be attributed to Rock Hudson's status as a celebrity. But the replayed visuals of his scenes with Doris Day, Elizabeth Taylor, or Linda Evans tended to reinforce Hudson's powerful image as the epitome of heterosexuality—an image that

the networks, presumably concerned about privacy, did not contest, since they kept largely silent about Hudson's sexual preferences in real life. Little wonder that the new image of AIDS was that it was at last hitting home.

Yet what is most striking about this phase of reporting is the new legitimacy accorded to topic-driven stories about AIDS and to sources, notably in the gay movement, that had been absent in the preceding several months. This new concentration also provoked agencies, such as the National Institutes of Health, to be more proactive than reactive.[59]

According to Ann Thomas, director of public information at NIH, "After Rock Hudson, instead of responding to reporters, we were so nicked by the criticism why weren't we doing more that we decided to give more backgrounders and sent out more press releases." At this point Fauci was designated as the principal source for reporters (Thomas, comments on panel "NIH Announces AZT," Harvard School of Public Health, April 1990).

Not only did the new legitimacy allow the networks to develop longer stories and special segments on AIDS; it also pushed AIDS stories earlier in the broadcast, thus according them more importance, and allowed the "old news" story of gay men with the disease to reappear.The initial reports, on July 23, 1985, described Hudson's hospitalization in Paris and reported speculation of his having AIDS. On the second day of this story, two networks, in rare lead stories, not only confirmed reports that he had AIDS but also used the opportunity to report broader aspects of the AIDS story.[60]

CBS, July 24, 1985; NBC, July 24, 1985.

CBS developed the story of experimental drugs, using, as the rationale, Hudson's attempt to be treated in Paris with HPA-23. NBC further broadened the story by presenting an extensive report on the stress experienced by health care workers and AIDS patients in the clinic at San Francisco General Hospital. For the first time in months, instead of reporting primarily on hemophiliacs or other people with AIDS from atypical locales or groups, the networks showed gay people with AIDS—and treated them with respect. On July 25 all three networks led with the news confirming Hudson's diagnosis of AIDS and also examined other aspects of the AIDS story: ABC reported on the development of experimental treatments; this report was followed by a lengthy question-and-answer session between anchor Peter Jennings and medical editor Timothy Johnson on the transmission of AIDS. CBS reported on the development of experimental treatments. NBC reported on fund-raising efforts in Hollywood, and Tom Brokaw interviewed Dr. Paul Volberding, the AIDS clinic director at San Francisco General Hospital, on AIDS transmission. On July 26, after perfunctory reports on Hudson's condition, ABC described the AIDS clinic at San Francisco General Hospital, and NBC recounted the development of experimental drugs. Then, on July 28, ABC described fund-raising efforts such as a ten-kilometer walkathon in Hollywood. In late September ABC presented a week-long series of reports on theorigins, extent, transmission, cures, and treatments of AIDS and, even more unexpectedly, on AIDS-related complex (ARC), which had been previously unmentioned by the networks.[61]

September 23, 24, 25, 26, and 27, 1985.

Even on the day of Rock Hudson's death, October 2, NBC recapitulated general information about AIDS.To be sure, in many ways coverage merely revived a wealth of familiar storylines. CBS's Dan Rather resuscitated "an epidemic of fear that seems to be spreading faster than the disease."[62]

September 9, 1985.

The principal stories were related to schoolchildren with AIDS: an unidentified second-grader in Queens and, what was better for the news, the ongoing saga of Ryan White.[63]The first Ryan White story appeared on CBS on July 31, followed by ABC on August 2 and NBC on August 16. All three covered the first day of school in Kokomo on August 26.

But coverage of fear also included people with AIDS who were barred from nursing homes; unwanted and thus unadoptable foster children of AIDS-afflicted mothers; and even extraordinary precautions at the Rajneeshpuram community in Oregon.[64]Respectively, ABC, August 2, 1985; CBS, August 2, 1985; ABC, September 5, 1985.

But the epidemic-of-fear story now concentrated less on frightened heterosexuals, particularly parents pulling their children out of school, than on gay men who were subjected to discrimination and violence. Thus, in one report CBS not only showed conventional incidents of fear—Houston police wearing rubber gloves when frisking gay suspects, a school board meeting in New Jersey—but also interviewed a man with AIDS who was suing to regain his job as a budget analyst in Florida.[65]

October 7, 1985.

In an NBC story gay men in Colorado expressed their concern about losing insurance coverage after a law was passed requiring blood banks and doctors to report HIV-positive individuals by name; and a CBS story reported discrimination against gay actors in Hollywood in the wake of Hudson's illness.[66]NBC, September 18, 1985; CBS, September 19, 1985.

ABC broadcast a "special segment" on violence against gay men and lesbians, with Jennings noting, "There's always been prejudice and violence against homosexuals and lesbians [sic] . But the public concern about AIDS and its connection to homosexuals has made it a more serious problem."[67]October 21, 1985.

The illness of Rock Hudson recertified AIDS as a newsworthy topic suitable for stories beyond breaking news. The authoritative sources that had dominated the coverage of AIDS prior to the revelation of Hudson's illness no longer held the upper hand, and the reappearance of AIDS as a newsworthy issue allowed gay spokespersons to add their perspective. But instead of maintaining a continuing high attention, the networks' interest again would decline in late 1985 and early 1986. In effect, the cycle may have begun again. After Hudson's death AIDS became old news, and reporters relapsed to an event-driven mode. Although

Hudson's illness ushered in a new phase of AIDS reporting, notable for its thoroughness and for its new sympathy to both gay persons with AIDS and gay-movement spokespersons, it did not last.

The Cycle Again, But With A Difference

Hope and despair. Those are the conflicting emotions evoked by two stories tonight.

CBS, September 18, 1986

Anchor Dan Rather's lead-in to two stories, one about the drug AZT and the other about the epidemic in Africa, shows how the AIDS attention cycle replayed itself with a difference. Already, in the fall of 1985, there had been a spate of epidemic-of-fear stories, but by the beginning of 1986, the topic-driven coverage provoked by Rock Hudson's illness had once again been replaced by a largely event-driven routine approach. And once again, news organizations relied on political officials and authoritative medical and scientific sources to indicate when an AIDS story was newsworthy.

But five linked characteristics distinguished the post-Hudson coverage. First, although the number of stories declined from the 1985 level, they were presented earlier in the news flow, and items were placed among the top stories—a status that had rarely occurred prior to the revelations about Rock Hudson.[68]