TOWARD A BIOGRAPHY

Finding His Voice:

William Grant Still in Los Angeles

On May 22, 1934, a few days after his thirty-ninth birthday, William Grant Still arrived in Los Angeles, completing a cross-country trip that signaled a new departure in his career.[1] Until then, he had pursued two parallel careers in music. He had established himself as a brilliant and facile commercial arranger and orchestrator who had quietly helped W. C. Handy shape the "classic" blues, contributed to a series of Broadway musicals such as Runnin' Wild, Rain or Shine, and Earl Carroll's Vanities of 1928, then worked on radio shows like Paul Whiteman's "Old Gold Hour" and "Willard Robison and His Deep River Hour." There may have been as many as a thousand such arrangements.[2] In the world of concert music, Still was among the most prominent and promising American composers of his generation. Three major works premiered over fifteen months in 1930 and 1931 convincingly demonstrated three ingenious new ways to express his African American heritage. "Africa was [a] sensation," he wrote of its first performance for full orchestra in Rochester in late 1930,[3] and the critics agreed. The ballet Sahdji and then the Afro-American Symphony, now his best-known and most widely performed composition, followed in 1931. This achievement, which drew on what he had absorbed from each of his two professional paths, was significant both for the history of American music and for his own career. It marked a major step in his emergence from the world of Broadway and early radio into the rarefied but less lucrative world of concert music, a difficult transition that he was among the

first of any race to negotiate. Indeed, the informal title, Dean of Afro-American Composers, was both a recognition of the wide appeal his art had attained and an intimation of the racial barriers he challenged but never fully overcame.[4]

When he left Wilberforce University in 1915, Still's prospects for any sort of career in music seemed gloomy. A connection, possibly through his late father, with the well-known Memphis-based bandmaster W. C. Handy helped him along. Handy hired him for the summer of 1916 and published at least ten early Still songs and arrangements.[5] Through his work with Handy, Still absorbed the blues tradition that the black elites of his boyhood had largely rejected; his playing and his arrangements for Handy in turn contributed something to the blues' widespread commercial appeal.

After his year of navy service Handy rehired him, this time in New York, for about two years (1919–1921). There, after World War I, Still became part of the blossoming world of black music and theater. He was soon working with such musicians as Eubie Blake, Luckeyth Roberts, Will Vodery, and other members of the Clef Club, a combination union/ booking agency for African Americans organized in 1914 by the late James Reese Europe.[6] In 1921–1922 Still was an orchestral musician in Sissle and Blake's landmark all-African American revue, Shuffle Along, featuring the African American blackface entertainers Miller and Lyles.[7]

Will Vodery, an early African American orchestrator of Broadway shows, musical director at the Plantation Club, and later the first African American to work as an arranger and orchestrator in Hollywood, gave Still's commercial career a major boost by introducing him to the bandleader Donald Voorhees.[8] Through Voorhees, Still found himself orchestrating Earl Carroll's Vanities and, presently, the radio shows that confirmed his reputation as an innovator in the commercial field. The "Personal Notes" show him to have been as active and arguably as influential an arranger as Don Redman or Ferde Grofé, both now much better known in that capacity. By early 1925 he was described in the New York Times as "orchestrator of much of the music for negro revues and other theatrical attractions."[9] Still may well have contributed the arrangements that drew this comment from the Times drama critic Brooks Atkinson in his review of the Vanities of 1928: "Stung by the jazzy lash of Dan [sic ] Voorhees and his squealing band, the music sweeps like a breaking wave."[10] The distinctive and widely admired style of arrang-

ing Still developed in the course of this apprenticeship is audible in a few surviving aluminum recordings of the "Deep River Hour."[11] There is much more to be learned about Still's influence on popular music in the 1920s, hinted at in Sigmund Spaeth's 1948 comment that "he continues to command respect as a creative musician, and it is impossible to estimate the extent of his anonymous contributions to the lighter music of America."[12]

At the same time that Still was leaving his imprint on commercial music, he was finding entrées into the exclusive world of concert music. Even in 1923, as he was muSical director, arranging and conducting for the short-lived Black Swan record label, orchestrating shows, and composing commercial songs like "Brown Baby" to suggestive lyrics over the pen name "Willy M. Grant," Still was going against the grain by studying composition in the European-based tradition. While he played in Shuffle Along during its Boston run, he studied with George Whitefield Chadwick, a prominent composer at the time and director of the New England Conservatory. Chadwick imparted the ideal of a "characteristic" American concert music to complement the ideas Still was already forming.[13] Later, in between Clef Club gigs and summer stands in Atlantic City, Still studied with Edgard Varèse. Varèse gave him the tools to express his musical ideas with greater freedom and introduced him to the avant-garde composers of the day and to conductors who would champion his concert works, then and in later years.[14]

After his two-year apprenticeship with Varèse, and after several of his concert works had been performed, Still came to understand that (1) he wanted to write concert music whose African American character was clearly recognizable to white audiences and (2) a "serious" African American style could not, by its nature, use much of the ultramodern dissonance to which Varèse had introduced him and at the same time reach the audience with which he sought to communicate. Still therefore decided to limit his use of "modernist" techniques to those that contributed to his own goals as a composer, an important step in developing his distinctive musical speech. The most important of the techniques imparted by Varèse to hiS further development was more subtle—the creative use of musical form.[15] The three works completed or revised after his 1930 visit to Los Angeles (the ballet Sahdji, the Afro-American Symphony, and the suite for orchestra Africa ) exemplify his racial style, as do the operas Blue Steel and Troubled Island . The shift away from Varèse's more obvious influences implied an eventual break with the insurgent white modernists of the day, a break based on culturally derived

aesthetic considerations and one with heavy long-term consequences. Still was clearly influenced in this move by the New Negro movement, even though his association with it was often more a matter of geographic and social proximity than direct, self-conscious intellectual participation.

In 1929, the bandleader Paul Whiteman sought out several African American arrangers for his enormously popular band.[16] Still, whom Whiteman judged the most successful of these, was signed as the band departed for Hollywood to make King of Jazz (released 1930). Still was hired, not to work on the movie, but to provide orchestrations for Whiteman's regular weekly radio broadcasts.[17] While the band was in Los Angeles, the broadcasts originated from the studios of Earl C. Anthony's KFI, the local NBC affiliate. Under the terms of his employment, he was expected to produce three arrangements—about thirty pages of orchestrated score—for each broadcast. He considered that rather substantial amount a light load. "Since I am a pretty fast worker, that gave me a great deal of time to myself," he said later.[18]

On his 1930 trip to Los Angeles, Still revived his friendship with Harold Bruce Forsythe, whom he had met in New York several years earlier, and met Verna Arvey for the first time, probably when Forsythe recruited her to read Still's music at the piano. Forsythe was already an enthusiastic advocate of Still's work; he played an important role in stimulating Still to complete the majoR works of his racial period. Soon after Still returned to New York City, the twenty-two-year-old Forsythe wrote about Still's early tone poem Darker America in some detail in "A Study in Contradictions"; his slightly later monograph on the ballet Sahdji is the product of considerable thought about contemporary literary treatments of African myth as well as familiarity with Still's score. It seems likely that Forsythe's ideas about the representation of Africa and of African Americans were especially valuable to Still, not so much because Still had not thought about them before (he clearly had) or because he agreed with FoRsythe (he didn't, especially about the "dark-heart"), but because with Forsythe he could talk about how these cultural issues might be represented in the technical language of music. Considering Forsythe's loquacity and Still's usual reserve, one imagines Forsythe doing a lot of the talking and Still sifting Forsythe's ideas in keeping with his own experience, his artistic sensibility, and his goals as a composer—including both the projects at hand and future projects, such as opera. Verna Arvey's role expanded as Forsythe withdrew after

the completion of Blue Steel; their separate contributions and Still's relationship with each is considered more fully in their separate chapters.

The short-term sojourn in Los Angeles while he worked for Whiteman was a productive one, as it turned out. Still planned out his ballet Sahdji, on an African subject by Richard Bruce (Nugent) that Alain Locke had proposed to him two or three years earlier.[19] He decided to add a prologue to be written by Forsythe, even creating a title page acknowledging his friend's contribution.[20] Still may also have thought about the Afro-American Symphony . The conception of a trilogy of symphonic works, portraying first the African roots, then the voices of African Americans, and finally the integrated, equal society for which he hoped, seems to have emerged here. Africa (1930), the Afro-American Symphony (1931), and finally, the second symphony, Song of a New Race (1937), eventually became the trilogy. At first Still had thought of Darker America (composed in 1924) as its first element. By the time Forsythe completed "A Study in Contradictions," though, Still had developed doubts about the work.[21] Though he disagreed with Forsythe on Darker America 's aesthetic value, Still remained interested in his friend's potential as an opera librettist.

Away from the tumult of New York and the turmoil of a failing marriage, Still found the time and the serenity in those months to think about his future as a composer. As one considers later developments in his career, it is clear that Still's early visit to Los Angeles affected him profoundly and that he hoped to return after his contract with Whiteman ended. Even as he worked on Sahdji and thought about the Afro-American Symphony and searched for operatic subjects, he was moving toward what became the next step in his stylistic development. He came to the conclusion that he would retain the range of characteristically African American expressions but that these would henceforth be among the wider variety of styles he might use, depending on the specific circumstances of a given composition. This developing "universal" aesthetic represented a further step, an understanding that he could compose with integrity without being self-consciously "racial." This was neither a retreat from his modernist experiments of the 1920s nor a rapprochement with the white modernists. It was, rather, a statement of his mastery of the musical language. He wanted his musical utterance to become one of many possible authentic American voices, and to write music that would communicate with all Americans. In his universal style, he asserted his freedom to speak in his music as the individual he was.

He settled into this style, or rather cluster of styles, after he returned to Los Angeles permanently.

One later example of his universal style is the music he composed for the New York World's Fair of 1939. His private response to winning the World's Fair commission reflected his pleasure in not feeling obligated to deal in stereotypically racial expression: "It seems to me that this must be the first time, musically speaking, that a colored man has ever been asked to write something extremely important that does not necessarily have to be Negroid, and I must admit that I can't help but be proud of the distinction."[22] In that same year, of course, his major compositional energies were directed toward a much larger African American-oriented project, his collaboration with Langston Hughes on the opera Troubled Island, based on a story from the revolution that ended slavery in Haiti.

Still understood that his first California stay coincided with his artistic maturity: "I think 1930 marked my real entry into serious composing. . . . [M]ost of the major works began in 1930 with that ballet, Sahdji, and the Afro-American Symphony ."[23] He wrote in his successful Guggenheim application of 1934, "I should like to go to California . . . for there I find an atmosphere conducive to creative effort."[24] In the later interview he remarked, "After I went back to New York from here, I was never satisfied. . . . California did something to me. . . . When I came here, it was like coming home."[25] No wonder, then, that Still sought an opportunity to return to Los Angeles to pursue his chosen goals.

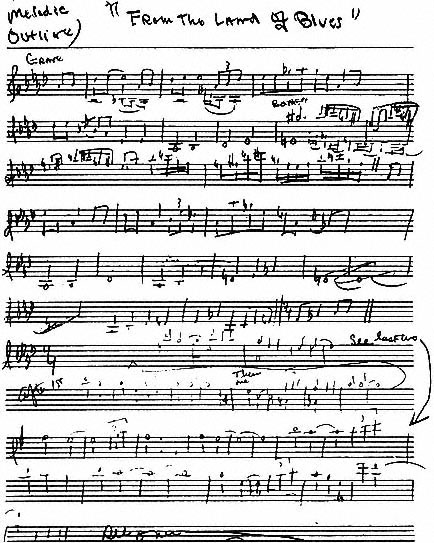

Still apparently made two attempts to provide music for Verna Arvey to perform after his 1930 visit to L.A. and before his return in 1934. A two-piano version of Africa (the first movement only) exists in the Still-Arvey collection, with "Verna," "Arvey," "Bruce," and "Forsythe" used to label certain repeated measures. Still attempted to adapt another work for Arvey to perform. Four Negro Dances, for solo piano and large dance orchestra, was commissioned by Paul Whiteman, most likely while Still was under contract with him or soon afterward.[26] The same work, under the title "The Black Man Dances: Four Negro Dances for Piano and Orchestra," exists in a pencil draft score in the Still-Arvey Archive. At the start of the pencil score is pasted in: "Acknowledging with gratitude the helpful suggestions of Miss Verna Arvey concerning

the preparation of the piano part." At the head of each dance is pasted a four-line stanza, each one signed "Bruce Forsythe."[27] The pasted-in texts appear to be an afterthought. Still's longhand note at the end of the score, "He can't dance any more," probably reflects his frustration that Whiteman would not release the work for Arvey to perform.[28]

From the time he turned away from the self-consciously "modern" in the interests of his creative integrity as an African American, Still characterized himself as "conservative," although his urge to work the various aspects of his life and his music into a coherent strand made him an innovator in spite of himself. The decision to leave New York was agonizingly personal as well, for he was under considerable pressure to emigrate to France. A letter from his wife, Grace Bundy Still, to Countee Cullen, dated December 9, 1929 (while Still was in Los Angeles with Whiteman), remarks, "I am eagerly awaiting the summer to make my first visit to France. I feel quite as you do about letting the children grow up there and as soon as possible after this proposed visit plan to begin looking about for permanent quarters for the family."[29] June 1930 found Still back in New York, unemployed and determined to use his time to carry out the projects he had developed in the course of his Whiteman contract. There is no evidence that he made a move toward a visit abroad. The declaration in his letter to Irving Schwerké of January 9, 1931, after six months without steady work and (ironically) just a few days after the Afro-American Symphony was completed, that he must soon either abandon music or "go where such conditions [of racial discrimination] do not exist" reflects his ambivalence about which geographic direction to take. The truncated journal of 1930 demonstrates that his marriage to Grace Bundy was very severely stressed after his return. We cannot follow this thread, for Still's journals over the next few years have not been found. We do know that before Bundy emigrated to Canada in September 1932 with their four children, Still had made his first application for a Guggenheim fellowship—to work in Los Angeles, not Paris.

Still's choice of Los Angeles over Paris carried implications that, whatever their personal dimension might have been, relate to the aesthetic choice embodied in his achievement of a racial style and his determination to develop it further, into a more universal speech. In large measure, the modernists had sought the "new" and learned their trade abroad; he had learned his trade with Handy in Memphis and on Broadway. The "new" he sought was developed from the African American

folk traditions he had set out to absorb and fuse into an "American" concert voice. From this point of view, his exodus to Los Angeles, grounded in an aesthetic choice, was a form of expatriation, not across the Atlantic, but westward, within his own country. In Los Angeles he intensified his efforts to bridge the gap that had developed between high modernism, based in New York City, and the traditional concert audience, which he wanted to expand across lines of race and class. Thus Still bucked a trend of stratification by genre through much of his career.[30] His decision may also have predisposed his critics to dismiss his work thereafter as no longer modern but merely commercial. To be sure, the commercial opportunities there made his personal decision easier.

"Serious" New York-based white composers often came to work in Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s (Copland is but one example). They tended, however, to separate this financially necessary movie work from their concert vocations geographically as well as aesthetically, marking the "seriousness" of their purpose by retaining their eastern residences. (That many of them had spent time in Paris and elsewhere in Europe in the 1920s was a further geographic credential.) European composers came to America, and to Los Angeles, to escape the horrors of Hitler's Europe and to carry on as best they could. Although the racial situation in Los Angeles had deteriorated after 1920, as it had elsewhere, members of the race nevertheless came to take advantage of the relatively less oppressive racial climate and the availability of commercial work, both factors in Still's decision to relocate there.[31]

In addition, Still had personal connections with some of the area musicians, some of whom were probably members of the segregated Los Angeles Musicians' Association, Local 767.[32] Before she joined the Fisk Jubilee Singers and eventually settled in Los Angeles, Sadie Cole had sung in a pageant written by Still's mother, back in Little Rock. Still may have heard Cole's daughter, Florence Cole Talbert, when she concertized in New York City (sometimes with Roland Hayes) in his Harlem years.[33] The success of Will Vodery, who had given Still arranging opportunities in New York and who had already broken the color barrier for arrangers in the movie studios, must have encouraged Still. There were family associations as well. Still's first residence in Los Angeles when he returned was on Thirty-fifth Street, where his near neighbors included both his cousin Charles Lawrence, a part-time musician whose music Still had

orchestrated some years earlier, and Harold Bruce Forsythe, who was Lawrence's tenant for many years.[34]

Once in Los Angeles permanently, Still reached out to the African American music community and beyond.[35] A gift of fifty scores and books on music to the Gray Conservatory and a talk, "Writing Music for Films," followed a concert at the Twelfth Street YWCA in which John A. Gray accompanied Leola Longress, soprano, in a group of Still songs, and Verna Arvey, the future second Mrs. William Grant Still, played piano reductions of Africa, Kaintuck', and La Guiablesse .[36] Kaintuck' was soon repeated for a predominantly white audience at a Pro Musica concert. Arvey, a diligent publicist, succeeded well in calling the attention of local white composers and regional music journals to Still's ability; Mary Carr Moore, for example, wrote of Kaintuck' as a work of "real power and splendid proportions" and became a regular at his performances.[37] Still's work was clearly perceived by much of the preémigré European American musical community in Los Angeles as not strongly associated with musical modernism, a plus from their point of view. The (mainly) white composers of the first Los Angeles school partook of the community's embedded racism but were nevertheless far more receptive to Still's aesthetic orientation than were the better-known modernists, many of the film composers, or the famous émigrés who began to arrive shortly after him.[38]

Still's first appearance at the Hollywood Bowl was at the head of the all-white, all-male Los Angeles Philharmonic on July 23, 1936. The Bowl had been a Los Angeles landmark since its founding in 1919 by an idealistic group of Theosophists, community activists, and real estate developers.[39] So it was appropriate that when Still became the first of the race to conduct a major symphony orchestra, it should have been there. As it turned out, his share of the program was relatively small. The unusually long first half of the concert consisted of standard European fare, an overture by Weber and a Brahms symphony, conducted by Fabien Sevitzky. After a late intermission, the advertised "American Music Night" began. Still conducted two excerpts from his own works: "Land of Romance" from Africa and the Scherzo from the Afro-American Symphony . His old friend and sometime rival Hall Johnson then led his own choir, the Hall Johnson Singers, in fourteen numbers, divided into three groups: songs from The Green Pastures, secular songs, and spirituals.[40] The fullest review, which appeared in the weekly Los Angeles Saturday Night, recognized that Still's share of the evening represented something less than half of the proverbial loaf:

Mr. Still very clearly demonstrated his ability as a composer in the two numbers which he conducted. The works are sincere, dignified utterances, written in a straightforward style. They present "an American Negro's concept of the land of his ancestors, based largely on African folklore, and influenced by his contact with American civilization." His orchestration is colorful, yet trickery has not been employed to achieve it. One cannot escape the feeling that the merit of these compositions warranted a performance in their entirety. As it turned out, we heard only "Land of Romance" from the Africa Suite, and "Scherzo" from the Afro-American Symphony .[41]

Forsythe subsequently wrote an essay on Hall Johnson and Still in which he celebrated the importance of this concert as a breakthrough for race relations in the concert music field.[42]

Still's music soon reached an even wider audience than that provided by the Bowl's popular concerts. Appropriately for a composer who had earlier contributed to the developing art of arranging for radio orchestra, schoolchildren and home audiences began to hear Still's serious music over the radio, thanks to the Standard School Broadcasts (sponsored by Standard Oil of California) that originated in Los Angeles. Between 1939 and 1955, more than thirty performances of Still's music, including perhaps twenty different works, were given on the Standard broadcasts. This led to broadcasts of music by other African American composers and, presently, to programs devoted to discussions and performances of jazz. These school broadcasts of jazz were said to be "the first radio-sponsored attempt to grant jazz a serious place in the musical world."[43]

More quietly, Henry Cowell's New Music Edition published the orchestra score of Still's tone poem Dismal Swamp, one of the early works composed in Los Angeles, thus giving him the imprimatur of at least one branch of the "ultramodern" movement.[44] The publication was supervised by the young Gerald Strang, then one of Schoenberg's composition students. There is no formal record of Still meeting Arnold Schoenberg, but if he did, it would have been at the symposium of new music organized by Arvey at the Norma Gould Studio in 1935.[45]

A vignette of Still and his family a few years after his arrival is given by Pauline Alderman, a member of the University of Southern California's music faculty. In 1942, her musicology seminar met every other week in her home.

Since three of the class members were working on American music projects, I had invited William Grant Still to come and lead an informal discussion on what he thought were the present needs of the American composer. . . . The

Stills came promptly, bringing their two small children whom they put to bed in my bedroom and we had just settled down for his introductory lecture when there were sounds of a siren and shouts along the street—"Lights out. An air raid." After the shock of the first moment we hurriedly blacked out the room, as all householders had been instructed to do, and Mr. Still went on with his well-prepared lecture.[46]

Although Still had lectured at Eastman at Howard Hanson's invitation in 1932, this would appear to be one of the few times he spoke at a southern California university. Later on, in the 1960s, there were numerous presentations at middle schools and high schools, both public and private.

Still had hoped to put his radio and theater arranging skills to work in Los Angeles, and he presently got his opportunity in Hollywood. In 1936, after the first Guggenheim stipend had run out, Still was signed to a six-month contract as a composer-orchestrator for Columbia Pictures by Howard Jackson, the studio's music director. With this chance for a good income came some in-house manipulations that unsettled Still. Jackson was fired on the day the contract was signed; Morris Stoloff was hired in his place. Still said of the incident, "That was some of the unclean practices in the studio, . . . politics and so on that got him out. . . . Stoloff, who was not a composer at all, . . . had never conducted."[47] Nevertheless, things went well for a time. He worked on several films, including Theodora Goes Wild and Pennies from Heaven, then produced a series of "sketches for the catalog." These consisted of short bits of music composed to support stock situations and kept on file to be used as needed. As was the case for film composers in general, Still himself did not have any way to know what was done with his sketches after he left the studio, but to judge from his ASCAP list, quite a few of them found their way into films.[48]

Columbia was best known for the numerous "B" movies that were its stock-in-trade. A prominent exception to its usual policy, the main feature Lost Horizon (released 1937) was filmed during Still's tenure there. Frank Capra, the director, hired Dimitri Tiomkin to compose the music; then, bypassing the inexperienced Stoloff, he hired a second experienced film composer, Max Steiner, to conduct and back up Tiomkin. Eight outside orchestrators were brought in to work alongside Still to speed up the project.[49] Still had seen nothing remotely like this musical overkill in his radio days. Given the lack of confidence in his skills that

Figure 1

Still at the piano, probably at Columbia Pictures.

Courtesy of William Grant Still Music.

this extravagance implied, he was sure that his contract would not be renewed once his six months were over. As a sort of desperate joke, he penciled into a section of quiet background music an inappropriate trumpet solo, "The Music Goes Round and Round," intending that it be erased after the rehearsal. The studio moguls, who wanted their swollen musical forces to work at white heat to keep their costs down and were doubtless worried about the change in policy represented by Lost Horizon, did not see anything funny about it. Later, Still said, "I was let go . . . [because] it doesn't look well to have a composer in the organization [and then] to go out and bring in people."[50] Columbia may have fired Still, but both Steiner and Tiomkin recognized his talent. Soon after leaving Columbia, Still completed a short job for Steiner at Warner's. Tiomkin sent orchestrations his way several times later on.

A few years after his stint at Columbia, Still took part in a published symposium about music in films, along with such composers as Marc Blitzstein, Paul Bowles, Benjamin Britten, Aaron Copland, Henry Cowell, Hanns Eisler, Karol Rathaus, Lev Schwartz, Dmitri Shostakovich, and Virgil Thomson. The symposium was conducted by mail;

Still's increasing conservatism would likely have led him to avoid a gathering of these liberal-to-leftist men, several of whom he had come to distrust. The remarks he wrote for this symposium constitute his most extensive statements about composing for film. What he had to say also reflects his short and tenuous relationship with the studios, his awareness of his position as the only African American in the group, and, indirectly, his grasp of the possibilities of film music. The unpretentious directness of his remarks contrasts sharply with the posturing of some of the other respondents. Unlike his fellow composers, who claimed compositional autonomy for their film music, Still wrote that he had worked only on the music director's orders, from the completed film sequences, thus frankly admitting that he never had any control over the overall product:

I never took into account the level of musical understanding of the film audience, but from the instructions given me by the musical director it was my opinion that he did. . . .

The difference in the music for a film and for any other dramatic medium is great; in the former, quality does not count so much as cleverness and perfection of the time-element. . . . Yes, the future cutting of a film makes it more difficult to write good music for films, as one is never sure whether or not a carefully worked out form or balance will be destroyed in the final cutting. . . . There are no more special facilities of sound-recording for films than there are in radio; personally, the resources in modern radio appeal to me more. . . . I have long felt the need for drastic changes in the conditions under which most film music is composed, and most other serious composers who have been momentarily attracted to this work agree with me, but such changes would involve changing the film industry itself, and this is impossible. . . . [T]he serious composers therefore have no recourse but to adapt themselves to Hollywood—they early learn that they cannot expect an industry to adapt itself to them.[51]

Still's best opportunity in films came late in 1942, when he was asked to be music director on a film with an all-African American cast, Stormy Weather, at Twentieth Century Fox. It was his biggest contract ever, for $3,000, but he walked out on it a few weeks after he was hired, apparently over the issue of how African Americans and their music should be represented in film. Although Still was never able to persuade the studios to use his concert music, it appears that, probably in the early 1950s, he produced a "Laredo Suite" from which excerpts were used as fillers in television series such as "Gunsmoke" and "Perry Mason."[52]

One of Still's projects after completing Blue Steel was a musical portrayal of Central Avenue, the center of African American life in Los

Angeles, probably intended for a film production.[53] Something of a mystery surrounds this score. Forsythe agreed to provide a scenario in 1935; the original idea was very likely his.[54] Still offered it to Howard Hanson for a ballet production at Eastman and then withdrew it. Not long after this, Still became one of six composers commissioned by the CBS radio network to compose a work specifically designed for radio orchestra.[55]Central Avenue was quickly revised into a suite specifically for broadcast, becoming New York's Lenox Avenue and scoring one of a series of national successes that came to Still in the first fifteen years of his Los Angeles residence. Later, Lenox Avenue became a ballet, with a new scenario by Arvey.[56]

Still applied for the Guggenheim and moved to Los Angeles to compose an opera, or possibly two of them. By the time he stopped composing in the late 1960s, he had completed eight operas. Only the second, Troubled Island, had a major production in his lifetime. That disappointment did not prevent him from continuing to compose them. Still's commitment to opera went back to his days as a teenager in Arkansas when he was enthralled by the early Victor Red Seal opera recordings his stepfather brought home. Donald Dorr details several of his unsuccessful early attempts to find or develop a libretto, the most serious (discussed above) involving an unpublished novel by Grace Bundy Still, his first wife, and Countee Cullen.[57] One result of the 1930 visit to Los Angeles was that Still was able to complete several symphonic works; a second result was that he began to seek out the long-term financial support necessary to compose an opera. In 1931–1932 he applied to the Guggenheim Foundation: "I am planning two operas. The scene of the first is to be laid in Africa, and its music will, in as far as artistically possible, reflect the primitive and barbaric nature of the African savage. The scene of the second opera is to be laid in the United States, and its musical idiom will be that of the American Negro."[58] This first proposal was not funded, but a second application two years later was successful. Thus his drive to become an opera composer was what enabled him to make the move away from New York City. A single scene by Forsythe, "The Sorcerer: A Symbolic Play for Music," which Still set as a ballet in 1933 and discarded later, may have been intended as part of the "primitive," "barbaric" African opera. By the time of his second application, he had chosen the second of his two ideas as the primary project and proposed a third as his backup.[59] ? He chose to set Blue Steel, a short story

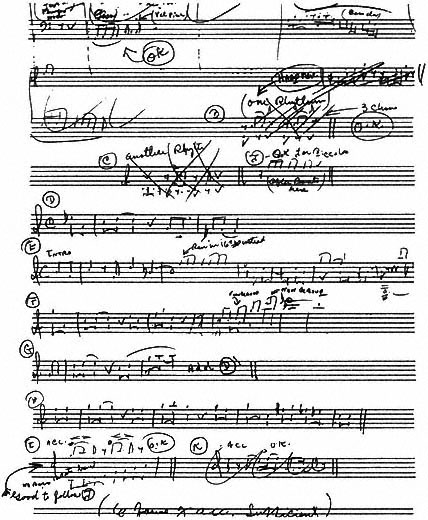

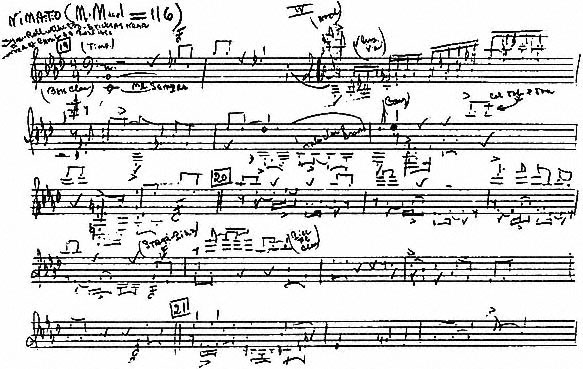

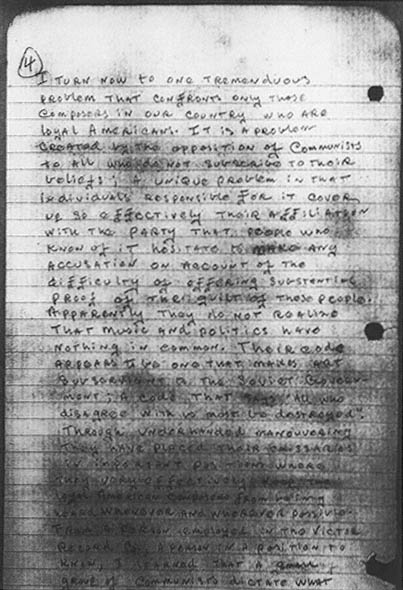

on an American Negro subject by his friend Carlton Moss, a writer just getting started in radio.[60] From the story, he developed his own very detailed dramatic outline for his setting, almost a libretto in itself, for Forsythe, his inexperienced librettist, to work from. Still intended his outline to present "roughly and concisely the gist of the lines which are to be given each character, and the stage directions.[61] Forsythe apparently accepted Still's working conditions, making his own notes on the outline and supplying language to suit the composer's specifications. Still annotated the libretto liberally, writing down motives and their variants. After Blue Steel was finished in 1935, Forsythe signed a contract to write a libretto for a full-length "Sorcerer," but he probably never completed it, and the second opera was not composed.[62]

Although both Arvey and Judith Anne Still came to regard the occasionally dissonant musical language of Blue Steel as the reason the composer rejected this first opera, it was not withdrawn until several years after it was completed, when Still, who was unable to convince the country's major opera companies to look seriously at it, had a newer one to promote.[63] Sadly, Blue Steel remains unperformed. The next opera, Troubled Island, set in Haiti to a libretto by Langston Hughes (with additions by Verna Arvey), eventually achieved a pinnacle of success for an American opera, a professional production by the New York City Opera. This production and its aftermath formed a major turning point in Still's life; so troubled was it, and so troubling for students of Still's life and works, that it will be treated at some length in another chapter.

Still did not allow his unhappiness over the treatment of Troubled Island to interfere with his commitment to opera; in fact, he continued to complete them at a remarkable rate. A Bayou Legend and A Southern Interlude were completed before the New York production of Troubled Island ever came about. Another opera, perhaps his best work, was composed entirely in 1949, the traumatic year of the Troubled Island production. Still worked out the outline for Costaso in the two weeks before he went East for the rehearsals and premiere of Troubled Island . Within a year he completed the entire score, down to extracting the orchestral and choral parts, then proceeded without a pause to the next project, Mota, on which he worked just as expeditiously. Once he was well settled in Los Angeles in his quiet domestic life with Arvey, it appears that Still purposefully embarked on a long-term project to use the various cultures of the Americas that were a part of his racially mixed background and his life in the Southwest as settings for operas. Arvey became his librettist for this project mainly by default, after Forsythe

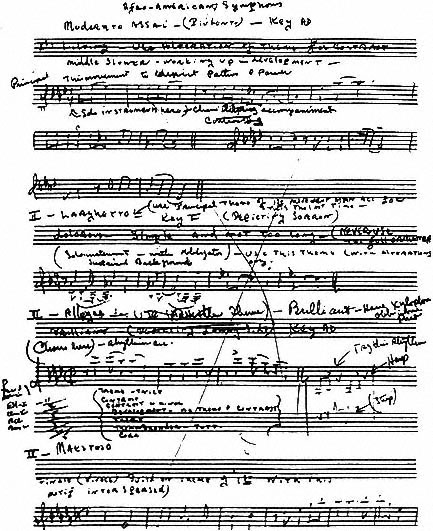

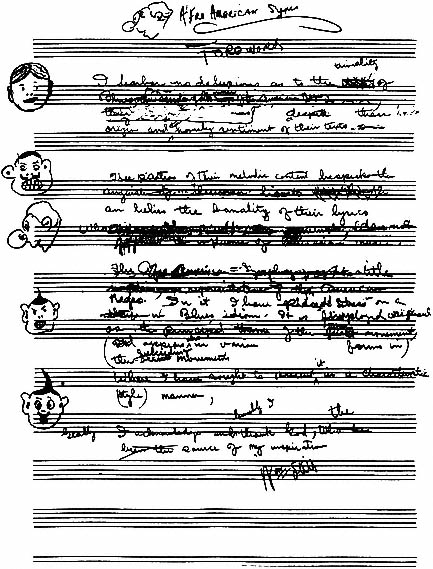

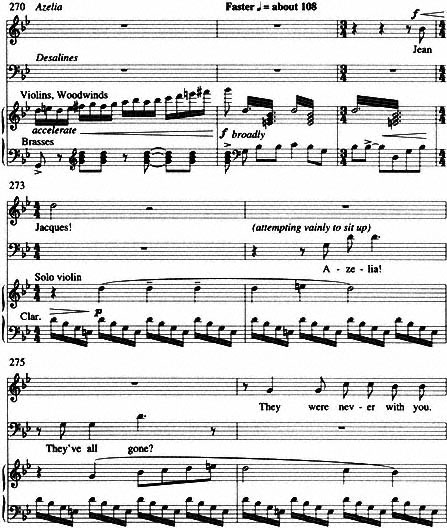

Figure 2.

Page from Forsythe's libretto to Blue Steel, with Still's annotations.

Library of Congress.

From the collections of the Music Division, Library of

Congress. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

and Langston Hughes (for different reasons) dropped out of the picture. (Still had always wanted his librettists close at hand, where they could write words to fit his music rather than the other way around.[64] ) A Bayou Legend (1941) and Minette Fontaine (1958) are set in Louisiana and draw on voodoo practices. Costaso (1950), reportedly Still's own favorite, is set in a Hispanic town in an isolated, austere southwestern desert. Mota (1951) is set in Central Africa; The Pillar (1955), in a Native American pueblo; and Highway 1, U.S.A . (begun in 1941 as A Southern Interlude and revised into a one-act opera in 1963), in the eastern United States, where it portrays a family whose culture is generally "American" but not racially specific.

Since the 1949 production of Troubled Island, none of Still's operas has been produced by a major company, although most have had regional productions of varying quality. By the late 1960s, when regional opera companies and university opera departments began to produce new American works more frequently, Still was no longer in a position to take much advantage of this new and fruitful trend. At this writing, Mota and The Pillar, like his first opera, Blue Steel, remain entirely unknown to operatic audiences.

Los Angeles gave Still a relatively relaxed racial climate, a friendly aesthetic atmosphere, and just enough support so he could pursue his career as a composer. His choice to remain there, away from the center of things musical, represents a going against the grain for composers of symphony and opera. His decision to turn down the opportunity (in 1941) to become a "university composer" at Howard University (at Alain Locke's urging) affirmed his decision to turn away from the worlds of both the modernists and the Harlem Renaissance, a kind of expatriation in his own country. Over the years the defeats added up alongside the successes, partly because Still aimed so high and attempted so much: his firing from Columbia Pictures, the summary dismissals of Blue Steel and Troubled Island by the Metropolitan Opera, the years of struggle before Troubled Island was produced at the New York City Opera and then its equivocal reception, the debacle at Fox Studios over Stormy Weather, the lapse of fifteen years before another opera got a hearing (Highway 1, U.S.A., 1964, on public television), the obscurity and poverty of the 1950s and 1960s. The quiet domesticity of his second marriage gave him extraordinary freedom to compose, a freedom he used for almost unceasing work, but the relative isolation it brought may have stimulated the feelings of suspicion and distrust that he displayed in his

later years. One remembers Carlton Moss's description of him as a dinner partner at the Harlem YMCA in his youthful New York days:

This was as I saw it, Still's personality. The only time I saw him was at the dinner table at the YMCA in Harlem, which was the only really decent place to eat. He would sit there, and he had this habit of tapping his foot. He never talked about anything else but that music. Later on I always felt that, I was just an interlude. That I never talked to him about this lynching, or this problem, or what the NAACP was doing. I just listened to his loyalty to his music, and I got the impression that when he left me, wherever he went, he'd sit down and mess with that music. . . . [He was] very attractive. But he was always off, in another world.[65]

On his first visit to Los Angeles, Forsythe described him as "the most original and gifted negro composer ever to be in circulation," and wrote "there are few artistic paradoxes to compare with the artless simplicity of his personality and the uncanny complexity of his art creations."[66]

In the late 1920s and especially in the 1930s, Still had attracted substantial attention as a composer of art music, with numerous readings of his works by major symphony orchestras. This continued for some fifteen years and more after he moved to southern California. For example, Still's concert music had no fewer than ninety-eight performances nationwide in 1942.[67] A succession of commissions and first performances by major symphony orchestras around the country, the Hollywood Bowl appearance conducting the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the CBS broadcast of Lenox Avenue, the Perisphere commission, were more than most composers could hope for in a lifetime. Many of these works seem to be the product of the repeated challenges, personal and cultural, that he had faced in his early years, that confronted him anew as he made his way in New York, and that led him to leave New York for Los Angeles. To some extent, these challenges changed as he moved from his early struggles to his successes in commercial music, to his career as a "classical" composer, and to the conflicts of his later years. But the underlying themes remained and can be followed in his best-known work, the Afro-American Symphony, in his relationships with Forsythe and Arvey, and even in the development of his late political activism.

An Unknown "New Negro"

Harold Bruce Forsythe's training as a musician made him both an enthusiast and a wonderfully insightful commentator on Still's concert works, which were generally ignored by better-known writers of the Harlem Renaissance/New Negro movement. None of what eventually emerged from them comes close to matching the now-unknown Forsythe's vivid perceptions. I supplement his "Study in Contradictions" and "Plan for a Biography of Still" with this biographical study because of the quality of Forsythe's work, because of the significant artistic collaborations he undertook with Still, and because of his influence on Still's personal life.

Indeed, Forsythe's artistic and personal impacts on Still are not fully separable. To begin with, he was a powerful advocate and facilitator for the Africanist aesthetic position he read in Still's music. During Still's 1929–1930 sojourn in Los Angeles, Forsythe arguably served as a catalyst for several works Still produced at the end of his "African" period, immediately after his return to New York City. Forsythe played a role in stimulating Still to clarify his conceptions of the ballet Sahdji and the Afro-American Symphony, and probably also Africa, the suite for orchestra that Still completed in Hollywood in February 1930. An early title page for Sahdji in Still's hand acknowledges Forsythe as the author of a prologue, now missing.[1] Forsythe's availability as a librettist was a major reason for Still's return to Los Angeles in 1934. Indeed, Forsythe wrote the libretto (to Still's detailed specifications) for Blue Steel, Still's first completed opera, and he provided the start for a second, which turned

into a ballet, The Sorcerer, later withdrawn. Moreover, it was Forsythe who introduced Still to his future wife and later artistic collaborator, Verna Arvey. The romantic triangle that developed in 1934—discussed below—was the immediate cause of his estrangement from Still and Arvey, although there were underlying aesthetic issues as well. The complications of these personal relationships probably influenced the way in which Still's "universal" aesthetic developed, and possibly its timing. More concretely, they may have affected Still's decisions to withdraw or alter certain of his works composed around 1935.[2] Forsythe's importance may thus be even greater than "A Study in Contradictions" suggests. Before the gifted, vulnerable librettist/ scenarist/ poet disappeared from view he had played a major role in the lives of both Still and Arvey.

Forsythe was born in Georgia (July 14, 1908) and taken to the Los Angeles area when he was about five years old, possibly earlier.[3] He attended Manual Arts High School, where he was an older contemporary of Verna Arvey. The two established a friendship that lasted almost fifteen years, longer than his association with Still. Several years before he went to New York City to study, Arvey wrote about him in the Manual Arts weekly paper:

Harold Forsythe . . . not only composed one piece of music, but many. Music was his natural mode of expression; and as Miss Rankin says, "His music is beautiful thoughts, lovely ideas. While he is able to speak and write in exquisite language, he has also the happy faculty of explaining himself in music." His compositions, on first sight, have an almost disarming simplicity. One imagines that they are easy to perform, but in reality they are most difficult. He is indeed a sensitive soul, responsive to all musical impressions.

Although he has composed many songs, short piano pieces, a string quartet and a fantasia for violin and piano, he is remembered in particular here for several of his works which were performed in assembly.[4]

About a decade after Arvey's article, Forsythe wrote this self-description for the Hamitic Review, a short-lived Los Angeles literary magazine:

Whether I'm a writer-musician or a musician-writer is a matter that doesn't trouble me. I've always kept the two functions in separate psychic compartments. My musical education was received from Prof. C[harles] E. Pemberton of U.S.C., and Dr. Rubin Goldmark of the Juilliard in New York. Since one disastrous venture into public taste, my music has been held in reserve. Have composed an opera, a symphonic poem, a monody and various works for small orchestra, string quartet and voice. Adolf Tandler, Nicolas Slonimsky, Leonard Walker, Fannie Dillon and others have spoken of this music. Be-

Figure 3.

Harold Bruce Forsythe.

Courtesy of Harold Sumner Forsythe.

ing a peculiar cuss, Verna Arvey and Gladys Mathonican alone play and sing it. My literary studies have been entirely independent and secretive. I have written about a dozen books covering the field of novel, biography, poetry, drama, scenario, libretto, metaphysics and criticism. Much interested in Negro history, art, religion, magic. Associated with the composer, William Grant Still in an effort to articulate the subtler currents of ethnic sentience. First published stuff in W. Thurman's old Outlet, and his Looking Glass . Did some bad articles for the California Eagle . Wrote during its lifetime for the stormy Flash, a sharp little publication. Am more than happy to be associated with the Hamitic Review, and have in mind a series of articles that might be of interest.[5]

His sensitivity in response to a rather well-received recital and the "secretive " character of his writing suggest, at least in hindsight, his extreme shyness and vulnerability.[6] The references in this biographical sketch and other of his writings also suggest a chronicle of the African American intellectual connections he made in his midteens. Wallace Thurman, later a prominent Harlem Renaissance literary figure, attended the University of Southern California in about 1922, then published his Outlet, to which Forsythe contributed, while working in the post office alongside Forsythe's uncle around 1922–1923.[7] Thurman boarded with Forsythe's family for a time and was at least indirectly a mentor. Forsythe later wrote, "You see although never a 'friend' he's closely bound up in my life. He was a friend of my brother and boarded in our house when i [sic] was a stripling. Nietzsche, Hearn, Flaubert, all came into my life from the books Thurman left about the house."[8] Arna Bontemps, later a poet and novelist of the Harlem Renaissance, was in Los Angeles at roughly the same time; it is very likely that Forsythe knew Bontemps as well.

Bontemps's 1941 letter to Arvey, giving biographical information for one of her articles, describes his own Los Angeles background and gives a rationale for his family's westward migration that very likely parallels Forsythe's:

When I was three, my parents moved to Los Angeles [ca. 1905, from Louisiana; 1912. or 1913 for Forsythe]. The following year they entered me in the kindergarten of the Ascot Avenue school. I believe I was the only colored child in the room (and perhaps in the whole school at that time), and I still remember how amused and pleased my mother seemed when she visited the school and found me completely integrated into the group. . . . Kindergarten turned out to be an epitome of all my schooling. I am a product of neighborhoods in which relatively few Negroes lived and of schools in which we were always greatly in the minority. The same is true, I believe, of a good

many Negroes who grew up in Los Angeles in those days. . . . My parents were always anxious to put the South (and the past) as far behind as possible. . . . One by one, however, our relatives migrated to Southern California during my childhood, and a link with the past was established for me in spite of all efforts to the contrary.[9]

Coming to Los Angeles was in fact an old tradition for African American musicians, who were visiting regularly by the 1890s and often performing to mixed audiences in white-run theaters. Flora Batson, the Original Nashville Students, and Sissieretta Jones were among those who had concertized there before the turn of the century.[10] Forsythe might have heard Will Marion Cook's American Syncopated Orchestra in Los Angeles shortly after World War I. In Forsythe's teen years, the city was the launching point for bands of both races that formed in the West and traveled East as well, contributing to the development of jazz. Freddie Keppard played in Los Angeles just before his successful move East, as Paul Whiteman also had. Keppard's Olympia Orchestra, including New Orleans bassist Bill Johnson, later became "the first black dance band, and the first from New Orleans, to make transcontinental tours, as the Original Creole Band. . . . It was this band . . . that carried the jazz of New Orleans to the rest of the nation."[11]

Many African American musicians had come to Los Angeles to live before Forsythe arrived. The vigorous classical music activities of the African American community are chronicled most fully in the weekly California Eagle to which Forsythe briefly contributed. Music making in African American churches was very well established.[12] Forsythe may well have heard groups like the choir of one hundred white-clad African American women, choral singers from local churches, who joined several hundred more of their white sisters in a formal greeting to President Theodore Roosevelt in 1912, as he campaigned in Los Angeles for election on his third-party Bull Moose ticket and women prepared to vote for the first time.[13] The African American community was relatively small but well educated. John A. Gray operated a conservatory and wrote a weekly column in the Eagle . Arkansas-born and Los Angeles-trained William T. Wilkins, in whose conservatory Forsythe first studied piano, began presenting his students in recitals in 1914. Forsythe, according to his son, hung out at Wilkins's conservatory. His piano teacher there was Nada McCullough, a graduate of the University of Southern California.[14] After several decades of teaching, Wilkins's and Gray's students

would number well into the thousands.[15] Thanks to the work of Gray, Wilkins, and others, many of L.A.'s jazz musicians were, like Forsythe, classically trained, which means that they did more reading from arrangements and less improvising than was done in New Orleans or Chicago.[16] Later, Charles Mingus was among the products of this tradition.[17]

Forsythe must have known about Still from an early age, for a Still cousin, Charles Lawrence, also a musician, lived in the same close-knit African American neighborhood around West Jefferson and Thirty-fifth Street in Los Angeles where Forsythe spent part of his childhood. Still had orchestrated a piece by Lawrence in the early 1920s.[18] (Later on, Forsythe and Lawrence shared living quarters in New York City.) It is quite likely that Forsythe had begun to learn about the possibilities of the Harlem Renaissance and the "New Negro" by then and that he introduced Arvey to its new intellectual currents while they were high school students. (Perhaps they read Alain Locke's 1925 The New Negro together, discovering among its treasures the first sketch of Richard Bruce Nugent's "Sahdji.")[19] Their friendship suggests the likelihood that Arvey became aware of Still and his work much earlier than she might have otherwise and that her meeting with Still in 1930 carried more weight than one might think from her later statement that she had barely met him in 1930. It is at least likely that Arvey is the "'not much praised but altogether satisfactory lady'" of Forsythe's essay who already in late 1930 "has become sweet on him [i.e., Still]." The chronology as well as the dynamic of Still and Arvey's relationship began earlier than previously thought because of this friendship, a matter of considerable import. This hypothesis is strengthened by H. S. Forsythe's report that his father's friendship and working relationship with Still ultimately foundered over Arvey.

Forsythe was a gifted pianist, as Arvey recognized and as is confirmed elsewhere.[20] He may have been among the student pianists that Arvey, whose own skill is well documented, recognized as a superior performer. His training in piano and composition was in the European concert music tradition, a background he shared with Still as well as with many other African American musicians of his time. The training in composition he received (after leaving Manual Arts High School and the Wilkins Conservatory) from Charles E. Pemberton, who had been a working musician in Los Angeles since the late 1890s, would have been very much in a conservative nineteenth-century German tradition. Forsythe's

relatively early short piano compositions at William Grant Still Music, his graduation gifts to Arvey, are in the European tradition (characterized by him as French-influenced) and testify to his pianistic ability. Many songs now among the Forsythe papers reflect his conservative training in Pemberton's hands.[21] However, Forsythe later made arrangements of one or more spirituals "with a jazz flavor," according to the report of his and Arvey's friend Harry Hay, who sang the arrangements on several occasions in Los Angeles. Forsythe lists other now-lost compositions, including an opera and a lengthy symphonic poem. He wrote to Arvey about them,

I have been looking over my long Symphonic Poem, the Opera and a small pile of songs. All done three or four years ago. I THINK MY BEST WORK IS BEHIND ME. So I've another balm. Deaf like Beethoven and Franz, stoop shouldered like Mencken, I do my best stuff early, like Mendelssohn, Poe. (Don't tell me that's the only resemblance with such guys. Ah knows!!!)

But art is Not technique, knowledge, . . . it is inspiration. And as I look at the pages of the Symphonic Poem, a work NOBODY has read and studied but me mahsehf I get broody and sad as the devil. That Spring was gorgeous . . . the months of its composition. Each morning I awakened with music bubbling and trembling in the head . . . could hardly get dressed before dashing for pencil and paper . . . Never will forget the glorious day the climactic section was written . . . and that strange passage where the theme rises, like a phoenix from fire, in the trumpets from a rumbling chaos of polytonal trombones, cellos and contrabassi and fiddles, sul. G portamento.[22]

Forsythe's impulsiveness seemingly contrasts with his interest in neoclassicism, his general distrust of the modernism of which neoclassicism was a major aspect, and his respect for the training he received at the hands of the German-trained Pemberton. With some of his contemporaries, he formed a club whose sole remnant is a letterhead bearing the heading, "The Iconoclasts: 'Down With Tradition,'" dating from the 1920s.[23] In the early 1930s he produced a lengthy novel, "Frailest Leaves," which contains a short and highly imaginative lecture on the historical values of counterpoint. His profound ambivalence about modernism is clear from this extract. The lecturer, a gifted but floundering young artist trying his hand at teaching younger students indifferent to both his brilliance and the expressive power of music—transparently Forsythe himself, perceives the ambivalence of modernism's claims to objectivity. A few excerpts:

The perfectly worked contrapuntal exercise was the nearest thing to absolute communism we will ever witness. That is true, but it is at the same time the

more aristocratic of the arts. Everything is part of the whole, yet nothing is subordinated to it. Its parts have all the characteristics of the best among men. They have character, charm, purpose. They must vary their tendencies, yet remain true to their own destiny, they must be strong, yet not inflexible. And most important, and this is where most of us fail, in life as well as in art; the parts conduct themselves with courtesy, respect and regard, each for the other. This is the most stringent note in our art. We admit here no percussive discords, no appoggiaturas, but only prepared discords of suspensions.[ . . . ]

[ . . . ] It is not my purpose to denounce contemporary music, but to encourage you in a fuller understanding of it by drinking deep of these purer, more intellectual fountains. The intellectualism of modern music is more psychopathic than has been generally understood.[ . . . ] Above all, do not regard this as the study of a dead language.[24]

The unreconciled, conflicting currents in Forsythe's thought are complicated by his anger about the race barrier. He was acutely aware of his distance from his white friends, including Arvey, but did not hesitate to tackle prominent African Americans who did not agree with his opinions, including Clarence Muse, the prominent actor, singer, and composer, then a Hollywood fixture:

So darned mad at a Negro that for the moment I hate all of them. Clarence Muse. The most blankety-blankest idiot the Devil ever tossed upon the poor, long suffering Nig.[ . . . ]

Tomorrow I will be calm and contemptuous again. Today I'm rip snorting, and hating, and furious.[ . . . ] I could whoop for the Ku Klux Klan, if an equally asinine white man hadn't irritated me before C.M. got started.[25]

On recommendations from both Pemberton and Wallace Thurman, Forsythe was awarded a fellowship to the Juilliard Graduate School in New York City for 1927–1928.[26] There he studied composition briefly with Rubin Goldmark and theory with another, unidentified teacher. He withdrew from Juilliard on March 18, 1928, before completing a full year of study.[27] Harold S. Forsythe reports that Forsythe wrote to his mother from New York that he was having trouble with his hearing, something that he seems to have kept from his friends. Whether he was in New York City before the fellowship began and how long he was able to remain in New York City afterward are not known; his mother's letters to him reflect her taking on extra work and making other sacrifices to send him money. The fictional but autobiographical hero of his "Frailest Leaves" describes a brief, disastrous affair with the woman

designated by Goldmark to teach him; one of the few letters from his New York sojourn confirms a brief engagement.[28] His later letters from New York used as their return address the location of Thurman's Fire commune on 135th Street, suggesting both that he lived or worked there and that he had some association with Harlem Renaissance literary activity. Yet his self-descriptions listing a lengthy series of short-term jobs do not include a connection with the short-lived, flamboyant Fire . Likewise, his claim in the sketch quoted above to have studied with Varèse—Still's teacher—has not been verified and is not repeated in other places.

Forsythe and Still renewed their acquaintance during Still's sojourn in Los Angeles in late 1929 and early 1930, just before "A Study in Contradictions" was written. The implication is very clear that they discussed future projects; perhaps Arvey even participated in some of the discussions about whether Forsythe and/or Still were really more "African" than "Afro-American," and if so, how that quality should be reflected in Still's compositions. The later evidence is that they talked about subjects for operas and that Still acted on some of these discussions. One of Forsythe's proposals that Still did not accept or even acknowledge (so far as is known) was Forsythe's offer to complete the libretto of Roshana, the project Still had begun in collaboration with his wife, Grace Bundy.[29]

Forsythe had a hand in the sequence of events that brought Still back to Los Angeles permanently in 1934. In his first application to the Guggenheim Foundation for funding (rejected in 1932 but awarded for use in 1934), Still wrote that he planned two operas, one about black Africans set in Africa, the other about African Americans in the United States. He wrote, "The librettist has already completed a portion of the first act, and his work is well done."[30] From this it is plain that Still had decided on the subjects of his operas and on his collaborator before he applied in 1931 and probably earlier, before he returned to New York in 1930. The first of the two operas was to be The Sorcerer, for which Forsythe produced a one-scene libretto. In 1933, while Still was in New York, he composed a ballet to The Sorcerer, whose scenario resembles the libretto scene and is attributed to Forsythe. Four years later, Still sent the manuscript to Howard Hanson for a possible reading at an American music symposium in Rochester, scheduled for fall 1937. After expressing doubts about its value, Still withdrew it, not even allowing an orchestral reading in a closed rehearsal, then sent his orchestrated

version of his song "Summerland" from Three Visions (for piano) instead.[31] Still did not destroy this manuscript, which exists in the form of a seventeen-page piano score, but the orchestration is so far unlocated.[32]

The second opera, on an American subject, was to be Blue Steel . The libretto fleshed out a short story by Carlton Moss.[33] This is the project that Still chose to work on in Los Angeles. In keeping with the composer's manner of working on opera, Forsythe stayed obligingly close to hand, providing new or changed text as Still worked.[34] It is likely that at this time (1935) he wrote the essay on Still's ballet, "The Significance of Still's Sahdji, " which appeared in the Hamitic Review, probably in the same April 1935 issue for which he provided the self-description given in full above. Forsythe's essays on Sahdji show that he became deeply involved with the work; in the longer essay he claimed to have suggested that Still rewrite the final dance, something that Still later seems to have done.

There seemed every intention of continuing the collaboration following the completion of Blue Steel .[35] On May 21, 1935, Still and Forsythe contracted to collaborate on an opera called The Sorcerer and a ballet called Central Avenue .[36] In the first case, Forsythe was to provide a libretto for a story already "invented" by Still, no doubt an expansion of the earlier sketch/ballet or a movie short. In the second, Forsythe was to complete the scenario, already partly "invented" by Still, for a ballet. There is no evidence that the opera The Sorcerer ever went forward beyond the ballet Still had composed in New York. Central Avenue was composed and, according to some sources, discarded. Much of it resurfaced as the suite for radio orchestra and later ballet, Lenox Avenue, for which Arvey supplied the scenario. Letters from Howard Hanson and Thelma Biracree, who had directed and choreographed performances of Sahdji and La Guiablesse at Eastman, indicate that Still sent them Central Avenue and that Biracree and Hanson were very eager to perform it. Before it could be produced, Still withdrew it in favor of Lenox Avenue, whose scenario Biracree regarded as much less satisfactory for the resources available at Eastman. Lenox Avenue remained unperformed at Eastman, and the mystery of Central/Lenox Avenue remains unresolved.[37]

On the basis of their common interests in composition, the piano and its literature, and music criticism, Verna Arvey had maintained a longstanding, warm friendship with Forsythe that peaked in the eight or nine

months after Still's arrival. In August 1934 she wrote with unusual eloquence to Carl Van Vechten, a major patron and champion of the Harlem Renaissance, in behalf of Forsythe's literary production:

Aug 6, 1934

My dear Mr. Van Vechten:

. . . For the past ten years, I have known and written to Bruce Forsythe, a young Negro intellectual, writer and composer-friend of Langston Hughes, William Grant Still, Wallace Thurman, Richard Bruce, etc. His letters to me have been impersonal, yet filled with a most interesting view of the race situation in America today, various musical and literary thoughts which may or may not prove of value, comments on those famous colored people he has known and anecdotes, his own personal history, etc. Because they extend over a long period of time, the later letters are necessarily more mature. All of them are beautifully written.

I have compiled these letters into a book (with Forsythe's permission and approval)—and now I wonder whether you would be interested enough to read it, pass judgment and to suggest a possible outlet for it? For the last few years I have been writing articles and criticism of my own (mostly on music and dance subjects) for various and sundry publications.

If you are interested, may I call on you when I come to New York, or would you prefer that I mail it to you? . . . Sincerely yours, Verna Arvey[38]

Given this prodding, Forsythe put aside his earlier opinion of Van Vechten (expressed in "A Study in Contradictions") as "a mere surface polisher and wise-cracker" and wrote his own letter describing something of his life and his work as a composer and writer. He revealed his own shyness and vulnerability in the process:

[August 24, 1934]

Mr. Carl Van Vechten

Dear Sir:

Letters of this sort, which assume an enormous amount of importance to the writer, are very difficult to write. But after having postponed the writing of this one for several years I have at last reached a sort of serenity and perspective; and from this little perch I do not feel so much of my former fear of thus addressing you.[ . . . ]

It is simply that having never mailed a book or a piece of music to a publisher; having never really contacted a first-rate critic, and having, at 26, lived a sufficiently peculiar life devoted to such pastimes as dish washing on a diner, office boying, elevator operating, night watchmaning, janiting, soda jerking, shipping clerking, private secretarying, ditch-digging, editing a tiny magazine, studying harmony, counterpoint, orchestration, composition, with Goldmark among others, piano pounding in sweet houses, ditto on a steamer, ditto in jazz bands, ditto in vaudeville, book reading, and having

found time during this to compose with a minimum of exhibitionism a symphonic poem, an opera, innumerable smaller stuffs, and having loved and studied the [European art] Song. Hallelujah to Wolf, Franz, Debussy, van Dieren and composed three volumes of it . . . as well as about fourteen literary slices, many of which have been burned by this hand. . . . At last comes the urge to a more practical view of things, and a genuine view of what I have done. Since it is an axiom about starting at the highest perch I approach you in this manner. . . .

In all seriousness now, I have now a book. . . . In some respects a biography of my dear friend William Grant Still, that most brilliant (Musically) of all Negro musicians. This is not a conventional biography, but one told through a figure of personal and ethnic experience. The book not only places an entirely fresh evaluation of the "Spiritual" but takes a somewhat strange view of Jazz. At the same time it serves to throw into relief the work of a man known by few (if any). He has composed beautiful music . . . music of a far deeper spiritual and mental significance than any other Negro composer ever heard of. I am a musician. I compose. I am a Negro composer. Yet I approached this book with a beating heart for at last a composer of my blood spoke with something other than bilgewater spiritual derivations or sloppy sentimentality.[ . . . ]But Still's music is rooted in the Dark-heart. How deeply I show in the book.[ . . . ]

Very sincerely yours, Bruce Forsythe[39]

Within a few days, he wrote to Jean Toomer, expressing his great admiration ("you are not so much the finest but the only writer partaking of the Blood, in this country") for Toomer's novel Cane (1923) and its hero, Kabnis, and asking permission to quote from it in his own work.[40]

Forsythe busied himself with revision of the material he had agreed to send to Van Vechten, while Arvey prepared for her lecture-recital at the New School in early December and the warm-up performance in Los Angeles a month earlier. Perhaps it was the growing tension as her travel date drew nearer that led to the warmth of his letter to her, following her Los Angeles recital:

And since you are going away I do want to step outside everything, Verna. And say a final word. You may imagine perhaps, that to have known one person for many years, and to value them highly, and to almost live looking forward to their brief visits, and then when a stranger comes to town, to have that old friend suddenly cease . . . bingo! Do you realize you haven't set foot in my house since Bill came to L.A. Do you wonder that this hurt me, and caused me to say and do rude things. For I say for the final time; I have no utilitarian bone in my body. I love a few people very strongly and

for themselves alone. And am acutely sensitive where they are concerned. But tho it now is a matter of no importance, I still think as highly of Verna as ever since M.A.H.S. and suppose I always will in years to come when the silly causes of my foolish losing of your friendship have vanished, and you move in an entirely different group.[41]

Upon receiving a postcard reporting on her call on Van Vechten, Forsythe sent off not one manuscript but three, and enclosed a small snapshot of himself for good measure:

Dec 13, 1934

Dear Mr. Van Vechten:

[ . . . ]This novel, biography and romance are dear for several reasons, (none literary). They were largely composed in a fine old house in San Gabriel where I was attended to by my sister-in-law Irene, so lovely a person and so rare. I had no job then; and had only to write all day and drink and talk all night. At that time I had no thought of publication or of large minds. I wrote for the sheer love of it and because Irene wanted me to. There is no page in "Rising Sun" or "Maron-Mutra" that has not been discussed and rewritten, re-written and discussed by us for days on end. It was Verna A., however, who encouraged and insisted upon the revision of the novel when I disgustedly almost gave it up. . . . As in my first note to you I tried hard to explain my position and the peculiar way such colleagues as Wallace [Thurman] have always looked at me. I think that Still and I are a little more Negro than they are, a little more African . I do not remember ever showing anything to Langston Hughes who has had highballs with me several times. . . .

. . . Five feet eight, very thin, with an "agnostic stoop" (Moore?) Pale yellow face, . . . gray eyes, large mouth and heavy mustache (now). Much stronger than look. Played quarterback as kid and was handy with boxing gloves. Very shy at times and very pugnacious at others. Given to silence among strangers and wild monologues among friends. Like beer, port and scotch, and since 1928 have repudiated gaudy wearing and use only black from head to foot [ . . . ]

I praise heaven that my work on Still's opera is largely if not completely finished. . . .

Gratefully, Bruce Forsythe[42]

Van Vechten's answer, unlocated, stunned him to the point of incoherence:

Jan 15, 1935

I come just this once again with much humility, for I thank you deeply for your courtesy. And yet although I have boasted that I could take it, the air

is very bleak from the hint of doom in your letter. A year or two ago it would have thrilled . . . or even a year ago, for then I felt bursting with books and music, and the suggestion that these things are yet thin, and Future yawned brighter would have been terribly encouraging. But now . . . Many more lonely years ahead, and those years no doubt filled with the errors and foolishness of the past ones. This letter shouldn't be written of course, for it is just after reading yours, but I think a man who fears his emotions, or better, fears his fear is in some ways a coward, and of all virtues that is the least.[ . . . ]

Sincerely yours, Bruce Forsythe

P.S. If it were possible to explain the real reason for this sudden passion, after years of indifference to opinion and publication, I'm sure you would agree that it is not all mere ego and self-seeking.[43]

Van Vechten must have queried Arvey after receiving this letter, for she reported back to him:

2/5/35

When I returned, Harold seemed to be as he was, and showed me your letter. Strangely enough, and unlike the warlike old Harold, he seemed very meek and was constantly studying your suggestions to see where he could use them and thus help himself. More, he was very grateful to you for your frankness. He is going to revise "Frailest Leaves" now, according to your suggestions. In other words, (though this is small consolation for all the time and trouble you took in reading the mss., seeing me and writing to us) I think you have done Harold a far greater service by doing exactly what you did than if you had followed out your first idea, and, as a matter of fact, I think perhaps that is what I hoped for all along. Because a little personal triumph is relatively unimportant when it comes to making finer human beings of people! In the long run, I am sure Harold will profit more.[44]

Although Arvey tried to put a good face on it, Forsythe must have been devastated by what he saw as his failure, especially in combination with the loss of Arvey's friendship after Still's arrival in Los Angeles. Even without the sexual aspects of this triangle, Arvey had supplied him with a one-person audience and with knowledgeable encouragement for his creative work; now she focused these attentions on Still and away from him. We cannot know more ramifications than this unless Still's diaries, missing for 1931–1937, the period of his collaboration with Forsythe, are recovered, and perhaps more of Forsythe's materials. Arvey's annual datebooks are likewise lost, subsumed into five-year summaries that do not give sufficient information to make things clearer. The loss of Forsythe's letters to her, except for the half dozen from late 1933 and

early 1934 (just before Still's arrival) that are quoted here, becomes even more poignant in this circumstance.

Still family tradition has it that Forsythe was unable to live up to his side of the contracts for The Sorcerer and Central Avenue because of his alcoholism and that Still's piano piece, "Quit Dat Fool'nish," was initially intended as a bit of unsolicited advice for Forsythe.[45] We know now that the unusual contracts to supply librettos were somehow tied to the literary disaster that Arvey precipitated through her overture to Van Vechten as well as, perhaps, to the alcoholism. Arvey never lost her anger at what she perceived as Forsythe's self-destruction, and perhaps her guilt at having had a role in precipitating it. Later, in one of her "Scribblings," she acknowledged his early deafness (while he was studying with Pemberton, before he went to New York in 1927) and her belief that he had tuberculosis. In private, she summed him up this way:

HBF was a marvelous, strange character. He wrote wonderful letters. I admired them and compiled them into a book, only to discover afterward that he was a drunkard, that he lied about me, that he didn't like the book merely because I had arranged it Journalistically. He had whitewashed himself in his letters to make me know him as he wanted me to! One of the finest things in his life was his love for Irene, but even she grew disgusted after a time.[46]

Irene Forsythe, the sister-in-law who had encouraged him to write and allowed him to live in her comfortable house in San Gabriel, died in 1938, another severe blow. One imagines Forsythe destroying his manuscripts as he retreated noisily from his literary and creative friendships into the grinding poverty that was his family's lot.[47] Would he have continued as a musician? Although his name does not show up in the directories of Local 47, or in the surviving directories of Local 767, the segregated African American local that was abolished only in 1953,[48] Forsythe had once found employment as pianist on Prohibition era gambling ships anchored outside the three-mile limit, where they were free to sell alcoholic beverages.