2—

Ready-Mades: (Non) sense and (Non) art

Thought is produced in the mouth

—Tristan Tzara

Nonsense . . . is the sense of all senses.

—Raul Hausmann

Commenting in 1973 on Marcel Duchamp's ready-mades, John Cage underlines the originality of his contribution to the history of art, as well as his unique position among other modern artists:

At a Dada exhibition in Düsseldorf, I was impressed that though Schwitters and Picabia and the others had all become artists with the passing of time, Duchamp's works remained unacceptable as art. And, in fact, as you look from Duchamp to the light fixture (pointing in the room) the first thought you have is, "Well, that's a Duchamp." (emphasis added)[1]

Cage suggests that the ready-mades are unartistic, to the extent that even today they remain unacceptable as art. Compared to other Dada artists, such as Kurt Schwitters and Francis Picabia, Duchamp's interventions retain their uniqueness, since their humdrum appearance and resonant titles resist assimilation to traditional artistic idioms. Despite Duchamp's contacts with the Dada and Surrealist movements, his gestures retrospectively challenge these affiliations. The ready-mades redefine the relation of art and reality through the elaboration of the social and critical conventions that inform the "objective" reality of these terms. As Cage suggests, the ready-mades transform our experience of art and reality so

fundamentally that it makes us wonder whether our own commonplace reality is but an extension of Duchamp's challenge of the autonomy of art.

Following his experiments with chance in Three Standard Stoppages, and while sketching out the project of what was to become The Large Glass, Duchamp became interested in exploring the artistic potential of ordinary objects that he later entitled "ready-mades." Duchamp describes his chance discovery as follows: "As you know, in 1914, even 1913, I had in my studio a bicycle wheel turning for no reason at all. Without even knowing whether I should put it with the rest of my works or call it a work."[2] Duchamp's interest in the double status of the bicycle wheel as an ordinary object and/or artwork, suggests that it is this paradox, rather than the object itself, whose potential as a work began to intrigue him.[3] Commenting on his choice to label these works as "ready-made," he explains: "It seemed perfect for these things that weren't works of an, that weren't sketches, and to which no art terms apply" (DMD , 48). The label "ready-made" designates a work, which is "already" made by mass production, but whose readiness to be "made" into art is delayed by its technological history and whose terms are unassimilable to an artistic terminology.

Marking his supposed abandonment of painting, Duchamp's ready-mades embody his most radical critique and departure from artistic traditions. Because of their commonplace character as items freely available in any hardware store, the ready-mades do away with the very gesture that signifies artistic creativity: the intervention of the artist's hand. However, the elision of the hand as the constitutive artistic gesture is replaced by an intellectual intervention, akin to wit—understood as a form of sagacity that combines intelligence and humor. As Joseph Masheck observes: "The wit was in making a common object as remarkable as an art object and making a work of art as real as an ordinary thing at the same time."[4] Duchamp's recourse to wit, to an intelligence of the tongue, rather than simply an intelligence of the mind, reflects his efforts to rethink the notion of artistic creativity both as a material and conceptual mode of production. The ready-mades redefine the notion of artistic creativity, since they do not involve the manual production of objects but their intellectual reproduction. Duchamp's intervention consists in redefining their status, both as objects and as representations, for the objective character of the

ready-mades affirms their special status as reproductions that comment upon and question the representational function of art.

Duchamp's originality lies precisely in his elaboration of the ready-mades as critical gestures framed as ordinary objects. Despite their resemblance to sculpture, the ready-mades embody Duchamp's efforts to move beyond traditional means of artistic production by taking to task and objectifying the conventions of art as a medium for reproduction. The redundancy of the ready-made, both as ordinary object and as critical intervention, makes visible the preeminence of mechanical reproduction in redefining both the subject matter and the means of artistic representation. Rather than viewing Duchamp's gesture as a denial or even an abandonment of painting or sculpture, this study will demonstrate how the ready-mades speculatively draw on and reinvest the conventions of previous artistic traditions. The radicality of ready-mades, as both objects and critical gestures, lies in the fact that they embody the effort to rethink visual representation through the mediation of a poetic interpretation of language. They embody Duchamp's exploration of the contextual production of pictorial and linguistic meaning through puns.[5] More precisely, the ready-mades stage the interplay of sense and nonsense, since they are punning visual and verbal allusions to the meaning of art as a medium of reproduction.[6] In this context, non-sense is no longer opposed to commonsense.[7] Rather, nonsense implies the destruction of the referential status of both pictorial and linguistic meaning through its punning associations to different senses. The ready-made thus emerges as a rhetorical intervention, signifying Duchamp's strategic operation on the terms that have come to define the parameters of artistic experience.

While Duchamp has explicitly acknowledged his indebtedness to poets and writers, his dismissal of pictorial antecedents has often been taken at face value. Before proceeding to examine Duchamp's fascination for puns as linguistic and poetic machines, it is important to consider whether the pictorial traditions of the past may have provided him with models for rethinking the notion of pictorial representation as a rhetorical operation. From Leonardo da Vinci's (1452–1519) insistence on an as an intellectual process, to Giuseppe Arcimboldo's (circa 1530–1593) experiments with the linguistic and poetic foundations of painting, we see traditions that anticipate Duchamp's own efforts to "put painting once again at the service

of the mind."[8] By considering Duchamp's pictorial and poetic sources, this study will explore how he draws upon the traditions of the past and those of his Dada contemporaries in order to challenge the conventional definition of art through an elaboration of its conceptual potential. Even before arriving at the idea of the "ready-made" as an object, Duchamp had begun to explore the "ready-made" character of pictorial and poetic conventions that define our "ideas" about art. Thus, without knowing it, he had "opened a window onto something else" (DMD , 31).

Retinal Art and Conceptual Euphoria

Art is a mental thing.

—Leonardo da Vinci

Quel Siècle à mains!

—Arthur Rimbaud

Duchamp's explicit rejection of painting as a purely visual medium whose purpose is to incite "visual euphoria" must be taken, like his other pronouncements, with a grain of salt. Duchamp's objections to painting are strategic, rather than purely oppositional. They are less a statement of denial of the significance of pictorial traditions, than an effort to rethink the legacy of painting in conceptual terms. In an interview with Francis Roberts, Duchamp clarifies his position by affirming his interest in innovation, that is, an "ideatic" interpretation of visual painting:

In France there is an old saying, "Stupid like a painter." The painter was considered stupid, but the poet and writer very intelligent. I wanted to be intelligent. I had to have the idea of inventing. It is nothing to do with what your father did. It is nothing to be another Cézanne. In my visual period there is a little of that stupidity of the painter. All my work in the period before the Nude was visual painting. Then I came to the idea. I thought the ideatic formulation a way to get away from influences.[9]

Duchamp's commitment to "intelligence" that he associates with poets and writers reflects his effort to redefine pictorial language in new terms. Rather than remaining subject to the constraints of pictorial language, even when its figurative limits are strained and questioned through the emergence of abstraction by painters such as Cézanne, Duchamp challenges visual representation by exploring its conceptual, "ideatic" character. Duchamp's effort to innovate, that of "inventing a new way to go

about painting," cannot be seen purely as a dismissal of pictorial traditions. At issue is the question of rethinking the concept of innovation in terms that amount to new ways of drawing on pictorial traditions, thus enabling the rediscovery of art's conceptual potential.

The affinities between Duchamp and Leonardo da Vinci have been noted by Theodore Reff, particularly regarding their shared conviction that "art is primarily the record of an intellectual process rather than a visual experience."[10] This emphasis on intellectual rather than visual experience explains why both artists were "more concerned with formulating their ideas than with producing finished paintings, more excited by research than execution."[11] This interest in research, in the effort to rethink the relationship between science and art, is visible in Duchamp's extensive notes, which were published in exact replica, starting with The Box of 1914 (1913–14), which anticipates the project of The Large Glass, The Green Box (1934).[12] His initiative to publish them may have been inspired by the publication of Leonardo's notebooks in facsimile (circa 1900), as well as by Paul Valéry's seminal work, Introduction to the Method of Leonardoda Vinci (1894).[13] Like Leonardo's notebooks, Duchamp's boxes include sketches, notes, and word associations. Duchamp eventually includes in his boxes reproductions of his own works, however, thereby transforming the provisional status of boxes into actual works. These boxes document not only his research and technical efforts but also his thought processes, combining artistic and poetic methods. Rather than functioning merely as research prototypes, Duchamp's notes, sketches, and reproductions represent an effort to challenge the notion of the work of art as an objective product by redefining it as a process, the embodiment of intellectual, artistic, and technical methods. Anne d'Harnoncourt and Walter Hopps consider these compilations as "masterworks in themselves, as important as any of Duchamp's realized visual projects, perhaps more so."[14] Thus, both Leonardo and Duchamp expand the meaning of pictorial representation by exploring how it interfaces with science, with notational devices in the form of mechanical instructions and poetic constructions (lists of word associations, anagrams, and puns).

A rapid glance at Leonardo's Codex Trivulzianus reveals the deliberate mixture of verbal and visual information, so that a "whole diagram may be a play on words."[15] This is also reflected in Leonardo's writing style in

which his characters, written in reverse with the left hand, "cannot be deciphered by anyone who does not know the trick of reading them in a mirror."[16] By mediating the legibility of writing through mirrors, Leonardo inscribes the eye into written script. In doing so he awakens the viewer to the figurative aspects of writing, to its technical and conceptual dimensions. The presence of extensive word lists, compiled according to a logic of free association that veers from poetic usage to ordinary puns, documents Leonardo's obsession with language as a mechanism for the production of signification. These lists attest to Leonardo's ambition to technologize metaphor, since language, like vision, becomes an object of fascination, a game of mirror images.[17]

Despite his exhaustive investigations of language, Leonardo nonetheless maintains that painting, because of its visual character, may have an advantage over poetry. In his "Comparison of the Arts" Leonardo parodies the Renaissance distinction between the arts, which stipulates that painting is "mute poetry," while poetry is a "speaking picture":

If you call painting "dumb poetry," then the painter may say of the poet that his art is "blind painting." Consider then which is the more grievous affliction, to be blind or to be dumb! . . . And if the poet serves the understanding by way of the ear, the painter does so by the eye which is the nobler sense.[18]

Leonardo's comparison leads him to affirm the power of painting (dumb poetry) over poetry (blind painting), since he considers visual forms to be more universal than language, whose conventions vary with different cultures.[19] This defense of the visual power of painting, based on its ability to reproduce forms through exact images, is pursued by Leonardo, who tries to save painting from its association with manual work: "You have set painting among the mechanical arts!"[20] Leonardo suggests that both painting and writing, as modes of reproduction, share the same mechanical device—the hand: the instrument of the imagination (painting) and the handiwork of the mind (writing). Leonardo's faith in the visual image, as a universal language whose posterity is guaranteed, is challenged by Duchamp, who finds both the silence of the painter and the intervention of the hand unbearable, if not outdated. Duchamp reverses Leonardo's

dictum by abandoning painting because it is "dumb." Moreover, he redefines art in poetic terms, as "ideatic" rather than "retinal"—a possible pun on Leonardo's definition of poetry as "blind painting."

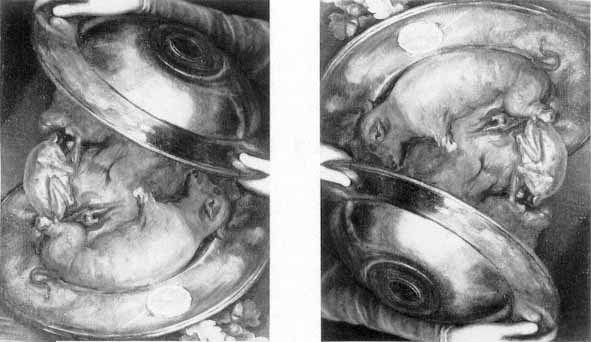

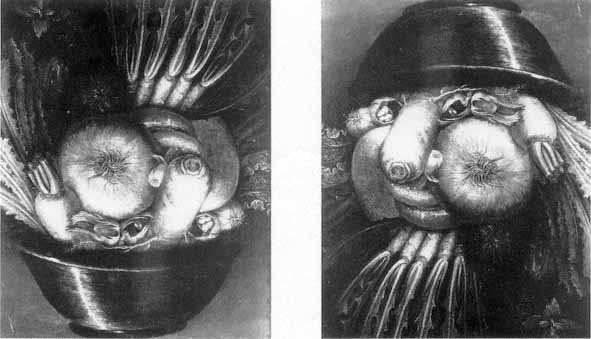

Duchamp's extensive quotations and allusions to Leonardo's paintings and his notebooks have obscured other possible sources of inspiration for his work. Duchamp's interest in verbal and visual puns, and specifically, his treatment of ready-mades as "three-dimensional puns," leads us to inquire whether there are other influences that are informing his work. Duchamp's sculpture-morte, which is an assemblage of marzipan vegetables and insects in the shape of a head, suggests Duchamp's indebtedness to the works of Giuseppe Arcimboldo.[21] Duchamp's appeal to an intellectual interpretation of art evokes the Mannerist understanding of concept as conceit (concetto );—that is, both as wit and as abstract schema.[22] The incongruous, witty, and monstrous character of Arcimboldo's paintings of Composed Heads captured the attention of the Surrealists as well. In these paintings elements of pictorial still life, such as flowers, vegetables, kitchen utensils, and cooked foods, are assembled in order to generate monstrous portraits. These allegorical portraits represent seasons, elements

Fig. 31.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, spring, 1573. Oil on canvas,

29 2/3 x 25 in. Musee du Louvre, Paris.

Courtesy of Giraudon/Art Resource, New York.

Fig. 32.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, spring, 1572. Oil on canvas,

29 8/10 x 22 1/5 in. Private collection, Bergamo.

Courtesy of Art Resource, New York.

Fig. 33.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, water, 1566. Oil on limewood, 26 1/10 x 20 1/5 in. Kunsthistorisches

Museum, Vienna. Courtesy of Art Resource, New York.

(such as air, fire, or water), or types of individuals (such as the cook or the gardener), by compiling both literal and metaphorical objects associated with each particular subject.

Spring (1573) (fig. 31) is a portrait composed of a variety of flowers with individual features that delineate the visible outlines of a woman's face, while another flower portrait, also entitled Spring (1572.) (fig. 32), suggests the features of a young man. These reversibly gendered images of Spring may be taken as a playful pun on its regenerative nature, and as a reflection of the hermaphroditic nature of flowers.[23] Such images underline the fact that the same material components—the flowers—may engender different figurative effects. The portrait of Water (1566) (fig. 33), which is both a physical and alchemical element, is presented through the grotesque assemblage of a dizzying variety of coiling fish, crustaceans, corals, and shells piled madly on each other—an assemblage suggesting the elemental, pagan, even primitive portrait of an alien being (a primeval sea goddess, or perhaps, an inhabitant of the New World). Initially The Cook (circa 1570) (fig. 34) and The Vegetable Gardener (circa 1590) (fig. 35) are represented respectively as a platter of cooked meats or a still life of vegetables in a bowl. On rotation, however, these images reveal the humorous semblance of the cook and the gardener, coded into the punlike reversibility of the meat platter or vegetable bowl.

These images encode into the visible a double register of perception: they are legible not only as the contents of a cooked plate or a bowl of vegetables but also as human heads. As Roland Barthes observes:

The identity of the two objects does not depend on the simultaneity of perception, but on the rotation of the image, presented as reversible. The reading turns around with no cogs to arrest it; only the title acts to contain it and makes the picture the portrait of a cook, since one infers metonymically from the plate to the man for whom it is a professional utensil.[24]

The rotation of the image reveals the fact that meaning is kinetic, since it is mechanically generated through the reversibility of the image. The perceptual unity of the image is fractured by a process of double legibility, suggesting its affinity to linguistic puns. This intellectual dimension of

Fig. 34.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, The Cook, circa 1570. Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 16 in. Private collection, Stockholm.

Courtesy of Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York.

Arcimboldo's paintings, the fact that they function on two levels at once, leads Barthes to conclude that these works function as a "terrifying denial of pictorial language."[25] While appearing to rely on pictorial traditions, Arcimboldo is violating the perceptual identity of the image by encoding within it several meanings at once. These images are visual puns highlighting the constructed and thus conceptual dimension of the visible. They reveal the fact that visual meaning is no more immediate or direct than linguistic puns, which unhinge meaning through the interplay of literal and figurative associations.

If Arcimboldo's work represents a denial of painting as a purely visual idiom, its intellectual impact can best be summarized in linguistic, poetic, and rhetorical terms. As Barthes concludes:

His painting has a linguistic foundation, his imagination is poetic in the proper sense of the word: it does not create signs, it combines them, permutes them, deflects them—exactly what a craftsman of language does.[26]

According to Barthes, Arcimboldo's talent lies in his poetic and rhetorical abilities—his exploration of similes, metaphors, and other figures of speech transmuted magically into objects. His painting represents a fascination with language and its rhetorical figures, so that the canvas becomes a veritable "laboratory of tropes."[27] Thus, Arcimboldo's paintings embody a marvelous reflection on the conceptual power of language, "the fact that in language there could be transferences of meaning (metaboles), and that these metaboles could be coded and to that extent classified and named."[28] Rather than enumerating exhaustively Arcimboldo's use of rhetorical figures, it suffices to note that his works present a theory of painting that is deliberately allegorical, to the extent that it designates itself as a system both of encoding and of decoding. Painting emerges in this context as a rhetorical gesture of deploying elements of pictorial still life in order to bring them to life again in the manner of lifelike portraits. Arcimboldo invokes the conventions of the still-life genre through the depiction of fruits and vegetables, only to divert these conventions into the service of portraiture. Rather than representing

Fig. 35.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, The Vegetable Gardener, circa 1590. Oil on wood, 13 3/5 x 9 2/5 in. Museo Civico

Ala Ponzone, Cremona. Courtesy of Scala/Art Resource, New York.

nature mimetically, he represents pictorial language as a "ready-made," that is, as a set of preestablished conventions. These pictorial conventions function like linguistic meaning: they are open to figurative interpretations, and consequently, to diverse rhetorical manipulations.

Instead of focusing on unifying forms, Arcimboldo's portraits draw our attention to the process of composition, to the fact that each element, whether flower, vegetable, or animal, retains its distinct (if muffled) existence. The composition of the image wavers and threatens to lapse at any moment into decomposition, thereby undermining its signatory role as the trademark of artistic creativity. This mutability, scripted into the image, is present at every level: it is a hinge structuring the relationship between individual details, as well as the reversibility or rotation of the image as an assemblage of diverse elements. The creative gesture implied in the composition of the visual image reveals its affinity to both poetry and humor, for composition signifies assembling elements already established by previous traditions, organizing them in a manner that both recalls and expands their original intent. Originality in this context becomes rhetorical, since it no longer signifies starting anew. Instead,the recovery of elements of pictorial still life in the service of portraiture leads to their reassemblage according to the logic of their literal and figurative potential.

Having briefly outlined Arcimboldo's contribution to painting, as a craftsman and poet of language, it is time to investigate his potential influence on Duchamp's putative abandonment of painting. Arcimboldo's recodification of the visual image in technical and mechanical terms may have influenced Duchamp's own manipulations of both images and objects. As this study will show, rotation, reversibility, and hinges are key devices to Duchamp's elaboration of the ready-mades, as linguistic and visual puns. The presence of these devices in Arcimboldo's works, which contributed to their status as "curiosities," makes visible a technical and mechanical dimension within pictorial traditions that predate the rise of industrialization. Even before Duchamp makes his own "discovery" of the idea of "ready-mades," Arcimboldo's paintings attest to the possible redefinition of painting as a rhetorical operation, which enacts the confluence and interplay of literal and figurative meaning. Duchamp's technical interest in rotation, reversibility, and hinges, all of which structure the production of visual and verbal meaning, leads him to explore puns as

conceptual machines. By actively staging the interplay of language and image, puns emerge not merely as humorous devices but as theoretical constructs expanding the notion of pictorial representation through linguistic analogues.

The discovery of the strategic role of puns enables Duchamp to abandon painting proper by providing a conceptual basis for art, understood as a medium that reassembles already given elements, and thus as a medium for reproduction rather than creativity, as it is understood in the conventional sense. Duchamp expands Arcimboldo's compositional strategies by recognizing the rhetorical character not only of pictorial representation but also of other forms of artistic representation. Arcimboldo's innovation thus does not rely on the creation of a new pictorial language but rather on the rhetorical deployment of its conventions as linguistic and visual givens. By understanding the conventions of painting as "intellectual ready-mades," Duchamp uncovers within artistic production a technical, "mechanical" dimension. In question is how the ready-made as a conceptual intervention and as a critical gesture literalizes the conventions of pictorial representation, only to expend their meaning through the redundancyof puns. Duchamp's ready-mades make possible a new interpretation of the notion of artistic production as a continued dialogue with the tradition, one which invites the spectator to complete the picture, as it were.

Puns: Verbal and Figurative Machines

It's true literally and in all the senses.

— Arthur Rimbaud

At certain moments even spelling-books and dictionaries seemed to us poetic.

— Novalis

When citing influences on his artistic work, Marcel Duchamp singles out the event of attending a performance with Francis Picabia and Guillaume Apollinaire of Raymond Roussel's Impressions of Africa in 1911. (Roussel [1877–1933] mechanized art-making and language in this book.) He describes this event as follows: "It was tremendous. On the stage there was a model and a snake that moved slightly—it was absolutely the madness of the unexpected. I don't remember much of the text. One didn't really listen. It was striking" (DMD, 33).[29] When questioned by Cabanne whether the spectacle struck him more than the language, Duchamp responded: "In effect, yes. Afterward, I read the text and could associate the two" (DMD, 34). The impact of Roussel's spectacle cannot be summarized purely in terms of its outlandish visual, mechanical, and

nonsensical character; equally significant is Duchamp's observation that the dissociation of the visual and linguistic aspects of the spectacle can be reassembled upon the reading of the text. Hence the text retrospectively illuminates the image, and in doing so, displaces the priority of both the visual performance and the text.

This anecdote becomes significant once it is understood that Roussel's interest in the mechanisms of language and his "secession" from literature corresponds to Duchamp's challenge to, and final abandonment of, painting.[30] Later, commenting on The Large Glass, Duchamp underlines the fact that the notes contained in The Box of1914 are essential to the visual experience of the work: "I wanted that album to go with the Glass, and to be consulted when seeing the Glass, because, as I see it, it must not be 'looked at' in the aesthetic sense of the word. One must consult the book and see the two together. The conjunction of the two things removes the retinal aspect that I don't like " (DMD, 42–43; emphasis added). This statement elucidates Duchamp's earlier assessment of Roussel's Impressions of Africa by defining his antiaesthetic position as a strategic interplay: the active dissociation and reassemblage of the visual and textual elements. Duchamp's expressed bias—that as a painter it was much better to be influenced by a writer than by another painter—indicates his effort to reinterpret art as "intellectual expression." His concomitant rejection of painting as "animal expression" reflects his project to overcome the purely visual (retinal) constraints of a medium that reduces the artist to silence, rendering him: "dumb as a painter."[31] This is not because the verbal is more "intellectual" than the visual; rather, it is the possibility of their interplay that arouses his curiosity. Duchamp's appeal to Roussel, as an answer to the crisis he perceives in painting, reflects his interest in the conceptual experiments with language through which Roussel challenged the very limits of literature.

Without being familiar with Roussel's writing methods—his experiments generating wordplays from sentences—Duchamp specifies his influence as follows:"But he gave me the idea that I too could try something in the sense of which we were speaking; or rather antisense . . . . His word play had a hidden meaning, but not in the Mallarméan or Rimbaudian sense. It was an obscurity of another order" (DMD, 41; emphasis added). The "antisense" that Duchamp speaks of here has neither

a negative sense nor suggests a hidden meaning, such as we find in the poetic experiments of Stéphane Mallarmé or Rimbaud. For Duchamp, "antisense" refers to Roussel's investigations of language as a mechanism that can generate "poetic" associations and to Jean-Pierre Brisset's analysis of language through puns.[32] Hence Duchamp's efforts to "strip" language "bare" of meaning, and thus explore its creative potential through "non-sense" (DMD, 40). This "linguistic striptease" liberates language from sense in order to open its field to the play of nonsense, that is, to the contextual generation of a variety of senses.

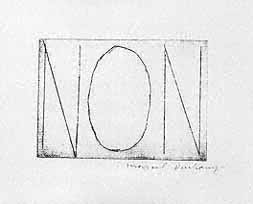

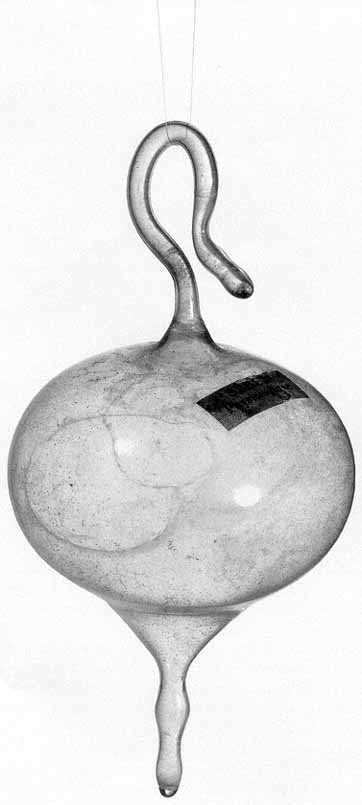

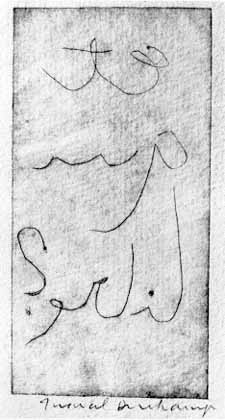

In order to elucidate what Duchamp means by nonsense, we turn to First Light (Première Lumière, 1959) (fig. 36), a work that explores the contextual production of pictorial and literal meaning through puns. First Light is a blue and black etching depicting the word NON, made to illustrate Pierre André Benoît's poem entitled "Première Lumière." What is striking about this etching is the fact that its status as an image or as a text is unclear. Are we dealing with the illustration of a poem, or merely the image of a title acting as a commentary on the official title? The relation of the image of the word NON and the title First Light is opaque as long as we do not shed light on this image with a pun. NON (both a negation and a particle of the French negative ne . . . pas ) is a pun on nom (meaning name or noun, in French). The "first light" that is cast on the word NON (orNOM ) reveals its fragile and conditional existence as a noun. NON hovers precariously between negation (a particle that brackets and derealizes

Fig. 36.

Marcel Duchamp, First Light (première lumière),

1959. Etching, 4 13/16 x 5 7/8 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise

and Walter Arensberg Collection.

the existence of another term) and nomination (a word that entitles an object or person).[33] The punning ambiguity between negation and nomination is further complicated by what appears to be the lack of reference to the title of the work First Light. However, once we recall Duchamp's subtitle to Given, "the illuminating gas" (a pun on gaze), it becomes clear that the discrepancy between the title and the image (which is like a title) reflects the difficulty of illuminating the image.

Duchamp's effort to reproduce Benoît's "creation" in this "literal" image results in the discovery that there are only "non-words" and "non-images," since neither the name (as image) nor the image (as a negative) has any intrinsic essence. Despite their nominative and essentialist character, the meaning of names, like those of images, depends on their context. Thus, both title and image are nonsensical to the extent that their ability to refer relies on the circuit of their interplay. Like Gertrude Stein, Duchamp discovers that "We must get rid of nouns, for objects are never stable."[34] The effort to provide a literal representation generates an excess of sense that spills out from the verbal into the visual domain, echoing Rimbaud's pronouncement: "It's true literally and in all the senses." Nonsense in this context no longer signifies "non-sense," but instead a gesture whose contextual character strategically stages and engages all the different senses.

Duchamp's active use and understanding of nonsense as a hinge between the linguistic and the visual defies the simplistic reduction of nonsense to a purely "literary" procedure. When Duchamp speaks of the poetic value of words, the "poetry" in question encompasses sound, wit, rhyme, and figurative considerations:

I like words in a poetic sense. Puns for me are like rhymes. The fact that "Thaï's" rhymes with "nice" is not exactly a pun but it's a play on words that can start a whole series of considerations, connotations and investigations. Just the sound of these words alone begins a chain reaction. For me, words are not merely a means of communication. You know, puns have always been considered a low form of wit, but I find them a source of stimulation both because of their actual sound and because of unexpected meanings attached to the inter-relationships of disparate words. For me, this is an infinite

field of joy—and it's always right at hand. Sometimes four or five different levels of meaning come through.[35]

Duchamp's interest in language is neither communicative nor expressive. His preference for puns, which he compares to rhymes, demonstrates his acceptance and use of chance. A pun plays on words that are similar in sound but different in meaning, just as a rhyme arbitrarily couples together two different verses. The sound of words produces a "chain reaction," in which "different levels of meaning come through," thereby producing an "infinite field of joy." As Duchamp warns us, the pleasure generated by these wordplays cannot be construed merely in terms of wit. Rather, for Duchamp, this pleasure is endemic to his description of intelligence: "There is something like an explosion in the meaning of certain words: they have a greater value than their meaning in the dictionary" (DMD, 16). In describing the meaning of intelligence, Duchamp is, in fact, distinguishing sense from nonsense. The intelligence that he has in mind is an intelligence of the tongue, an explosion of meaning whose verbal and figurative character defies the referential character of language. By situating intelligence, "right at hand," that is as a figurative principle generated through the play of puns, Duchamp stretches the logical limits of rational intelligence. His exploration of the plasticity of language, hinged upon its verbal and figurative associations, inscribes in his work a pleasurable dimension, that of an eros generated through their interplay.

Although Duchamp speaks of liking words in a poetic sense, his examples demonstrate that the poetry in question is conceptual, rather than "literary." Tristan Tzara's remark that "the poetic work has no static value, since the poem is not the end of poetry: the latter can perfectly well exist elsewhere," echoes Duchamp's own efforts to recover the plasticity of language and images.[36] As Duchamp explains in reference to The Large Glass : "I refer to purely mental ideas expressed as part of the work but not related to any literary allusions."[37] This denial of the literary captures Duchamp's understanding of his work as a new kind of language, one which rejects both literary and pictorial conventions, as well as the conventional meanings of words and images.[38] Michel Sanouillet considers Duchamp's strategy an effort to sunder the relation of expression to expressive content:

Once words are thus emptied and freed through the sudden visible strangeness of their internal structure or through a new association with other words, they will yield unexpected treasures of images and ideas. The adventure of language thus unfolds differently from the striving for style, which pursues freshness and visual and auditory sensations. The principle is that a word too much in view, like a landscape, loses its savor, wears itself out, and becomes a commonplace. The interest which its semantic content gives rise to is reduced to the vanishing point. It is only and precisely at the point where the stylist in search of the picturesque gives up that Duchamp intervenes. Once the container is stripped of its content, the word as assemblage-of-letters assumes a new identity, physical and tangible, as a surprising interpreter of a new reality. (WMD , 6)

Sanouillet's eloquent description of Duchamp's "adventure of language" suggests that this adventure applies equally to words and images, insofar as their meaning has been petrified and rendered commonplace through repetitive usage. Hence, Duchamp's experiments with puns emerge not merely as examples of self-expression, a gratuitous appeal to the private joke, but also as significant efforts to rethink the nature of both poetic and visual language.

Duchamp's interest in visual and verbal puns is expressed explicitly in his ready-mades. The selection and visual display of the ready-mades also involves the naming of the object, since the ready-made becomes a work of art by Duchamp's performance, by his declaration that it is such. Thus the title of the ready-made inscribes the object into a temporal and linguistic dimension. In his statement "Apropos of 'Readymades'" Duchamp explains: "That sentence, instead of describing the object like a title, was meant to carry the mind of the spectator towards other regions, more verbal" (WMD, 141). These titles are the expression of Duchamp's poetic concerns with language, his dynamic conception of words not merely as bearers but also as producers of meanings. Commenting on the title of the Nude, Duchamp remarked that it "already predicted the use of words as a means of adding color, or shall we say, as a means of adding to the number of colors in a work."[39] He also considered words in visual terms as "photographic details of largesized objects." Arturo Schwarz observes

that Duchamp was motivated by the desire "to transfer the significance of language from words into signs, into a visual expression of the word, similar to the ideograms of the Chinese language."[40]

Thus Duchamp's act of nomination of the ready-made is not a gesture of closure, that is, of framing the visual referent by a verbal one. The punning title of the ready-made stages the active interplay of phonetic and figurative elements, thereby engendering the destruction and dissemination of its objective character. Duchamp's understanding of words as mechanisms that may trigger a variety of associations enables him to manipulate the literal object-ness of the ready-mades. Like its title, the ready-made is more or less an object. Its meaning and existence as an object are validated by the act of nomination, but the title fractures the object to the extent that its literal and figurative dimensions interfere and condition our perception of the object. The title thus functions not purely as name but as a signifying material whose phonetic redundancies with respect to the object set up a relay of significations that displace and scramble the identity of the object. The redundancies and alliterations that come to define the object expend its objective character through nonsense.

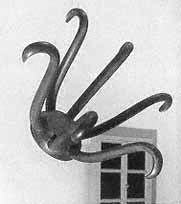

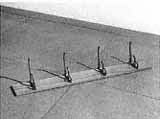

A quick review of Duchamp's ready-mades, a bottle rack, Bottle Rack (Egouttoir; 1964 version [original version of 1914, lost]) (fig. 37), a hat rack, Hat Rack (Porte-chapeaux; 1964 version [original version of 1917, lost]) (fig. 38), and a coat rack nailed to the floor, Trap (Trébuchet; 1964 version [original version of 1917, lost]) (fig. 39), reveal his interest in

Fig. 37.

Marcel Duchamp, Bottle Rack (Egouttoir),

1964 (original version of 1914, lost). Ready-

made: galvanized iron, height 25 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Fig. 3 8.

Marcel Duchamp, Hat Rack (portechapeaux),

1964 (original version of 1917, lost). Assisted

ready-made: hat rack suspended from the

ceiling, height 9 1/4 in., diameter at base 5 1/2

in. Galleria Schwarz, Milan.

Courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

Fig. 3 9.

Marcel Duchamp, Trap (trebuchet), 1964

(original version of 1917, lost). Assisted

readymade: coat rack nailed to the floor.

Galleria Schwarz, Milan.

Courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

exploring how physical displacement may be translated into logical and artistic paradoxes. The visual suspension of the bottle rack and the hat rack highlights their ambiguous status as ordinary objects. Hung from a support, they become inaccessible as functional objects. The coat rack, on the other hand, is rendered functionally redundant by being nailed to the floor. Floating in the air as if unattached, the bottle rack and hat rack draw the viewer's attention to the temporal, as well as visual, meaning of suspension—suspension as a brief interruption, or delay. Playing on both meanings of suspension, Duchamp inscribes a temporal interval into the visual dimension. In doing so, however, he reveals the nature of his intervention to be that of an intellectual fact, one which may "strain a little bit the laws of physics," to use his own terms. As he observes to Francis Roberts: "Even gravity is a form of coincidence or politeness, since it is only by condescension that a weight is heavier when itdescends than when it rises."[41]

Three of the ready-mades—the bottle rack, hat rack, and coat rack—are frameworks on which articles are hung, sharing the designation of rack (porte, as in the French porte-bouteilles porte-chapeau, and porte-manteau. ) Not only has Duchamp selected three objects that act as bearers for other objects porte (from porter, which is also door in French) but, lest his audience misses the joke, he has provided us with a further verbal clue with the coat rack (porte-manteau. ) A portmanteau is an artificial word construction that packs two meanings into one word. The coat rack (porte-manteau ) reveals Duchamp's understanding of ready-mades, not as actual objects but as porte-parole (spokesman or mouthpiece in English), that is, as bearers of speech or as mechanisms for the production of linguistic and visual puns. The visual suspension of these ready-mades reveals their affinity to puns, since puns suspend conventionalmeaning by creating an interval that delays their capacity to refer, by being objectified or "made" either into words or into images. As bearers of other objects and other meanings these ready-mades embody through their visual characteristics the mechanical displacements operated through puns.

In order to elucidate how puns function—not as ordinary words but as utterances—we return to Duchamp's coat rack Trap, which instead of being physically suspended is nailed to the floor. Keeping in mind Arturo Schwarz's observation that a "Ready-made is sometimes a pun in three-

dimensional projection," this work helps us clarify the relation of linguistic and visual puns in Duchamp's oeuvre. The visual meaning of this work, that of the physical displacement of the coat rack, remains quite opaque as long as we do not consider the conceptual displacement enacted by the title. The title of this ready-made, Trap (Trébuchet), is phonetically identical to the French chess term trébucher, meaning to "stumble over," thus suggesting both the kind of impediment (trap) and the kind of movement (stumbling) that puns engender. Susan Stewart has noted that puns "trip us up," and that they are an "impediment to seriousness" since they split the flow of meaning and events in time.[42] Yet, by making us stumble, puns invite us to think about language in a new way—not as a static object but as a mechanism generating movement. Considered in these terms, the so-called "poetic" or "creative" aspects of language emerge as "ready-made," to the extent that a pun is like a switch that mechanically enables us to discover the creative potential of language.

If Duchamp's work is a "pressure responsive mechanism" (to use Antin's expression), the linguistic and the visual elements can be considered as "trap doors" that open up kinetic possibilities. As Duchamp observes, "the trap door, and by its falling open/ the trap door effects the instantaneous pulling / of the carriage (through the system of pull cords.)" (Notes, 97).[43] The coat rack in Trap, on which clothes used to hang neatly in a row like words in a sentence, is a mechanical trap that unhinges our concepts both of language and of vision. The "linguistic trap" is the idea or rather conceit that "art could free itself from language" and "come to occupy a kind of neutral space between thoughts."[44] This illusion, that art can transcend language, is based on the mistaken assimilation of linguistics to literature—an assimilation that, in Antin's view, denies its conceptual and kinetic nature. The other trap in question is the "retinal" or "visual shudder," the illusion that an image or an object needs no further illumination since it is autonomous from language.

Duchamp's interest in puns as machines whose nonsensical character challenges the conventions of meaning is echoed by his Dada contemporaries' efforts to revolutionize both language and artistic modes of expression. For instance, Tristan Tzara's Manifeste de Monsieur Anti-pyrine and Manifeste Dada (1918) are neither purely discursive nor poetic artifacts but instead efforts to critique language itself as the purveyor of a logical

and metaphysical worldview. By setting into play the visual, graphic, and acoustic properties of language, through experimental typography that disrupts the conventional organization of words on the page, these manifestos challenge our presuppositions about the communicative or informational function of language. Like Hugo Ball's and Richard Huelsenbeck's optophonetic experiments, these texts are visual and acoustic performances that operate at the very limits of language. These experiments with language, however, must be distinguished from Duchamp's own discovery of puns as verbal and poetic machines. The specificity of the Duchampian project lies in the systematic elaboration of puns as embodied objects whose concrete identity is disseminated through verbal and visual reproduction. Instead of testing the limits of language, as do his Dada contemporaries, Duchamp uncovers within ordinary language a creative potential that reflects his understanding of it as a generative mechanism. As linguistic ready-mades, puns act like switches between common sense and nonsense, thereby technically reactivating and enriching their common usage. Their meaning is transitive, reflecting less their specific content than their strategic and contextual nature as utterances. By positing puns as mechanical prototypes, Duchamp invites the spectator to envision language itself in the mode of mechanical reproduction. Instead of just restricting himself to the nominal properties of ordinary objects, however, Duchamp proceeds to explore through the ready-mades their peculiar redundancy as both artistic and unartistic gestures.

What is a Ready-Made?

A work is a machine for producing meanings.

— Octavio Paz

When asked whether he considers the ready-mades in the same order of achievement as his other works, Duchamp replied: "They look trivial, but they're not. On the contrary, they represent a much higher degree of intellectuality."[45] In order to elucidate Duchamp's comment, consider in some detail the varieties of gestures embodied in the otherwise trivial appearance of the ready-made. What kind of object is the ready-made? Its three-dimensional character suggests its affinity to sculpture, while its commonplace character suggests that it may be a pun on the objective reality of the work of art. Is the ready-made an artwork or a critical gesture? And if the ready-made is not an artwork, how does it maintain its critical dis-

tance from reverting into a work of art? In this context, what becomes of the artist and the creative act?

The ready-made is the culmination of Duchamp's critique of artistic vision, a critique seeking to transform that vision, to undermine its optical verisimilitude by reinscribing it through verbal and cognitive activity. As the ready-made is often a commonplace object (a bicycle wheel, comb, snow shovel, urinal, and so forth), it engages the spectator in a new dynamic, one where the object is no longer defined by its visual appeal as an aesthetic object. The visual pleasure induced by the formal and material qualities of the object is not rejected; instead, it is deliberately avoided as an intervening criterion in the choice of the ready-mades. As Duchamp explains:

In general, I had to be beware of its "look." It's very difficult to choose an object, because, at the end of fifteen days, you begin to like it or hate it. You have to approach something with an indifference, as if you had no aesthetic emotion. The choice of the readymades is always based on visual indifference and, at the same time, on the total absence of good or bad taste. (DMD , 48)

The experience of the ready-made is one of indifference and anesthesia, since these commonplace objects have been selected because of their lack of "aesthetic emotion," as a defense against "taste" or the spectator's "look." This invocation of "visual indifference" marks Duchamp's turn away from the "visual" arts and toward an art that seeks to define itself in terms of its intellectual, rather than "retinal," potential. It is this lack of aesthetic emotion and taste that distinguishes Duchamp's ready-mades from subsequent experiments, such as the Surrealist found object (objet trouvé). The choice of the found object often relies on its visual appearance, its evocative powers, or its melancholic character.

But as Duchamp admits, no object can resist visual appropriation. Sooner or later, you begin to either like it or hate it, since the object is recovered under the aegis of one's artistic habits as either good or bad taste. How then does one escape taste? Duchamp's solution, in the context of his pictorial work, is to take recourse to "mechanical drawing," which according to him "upholds no taste, since it is outside all pictorial

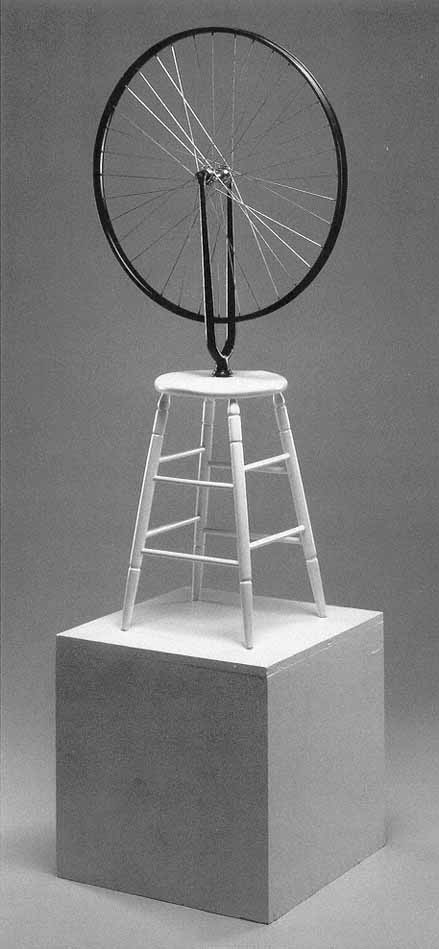

Fig. 40.

Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel (Roue de bicyclette), 1964 (original version of 1913, lost).

Assisted ready-made: a bicycle fork with its wheel screwed upside down onto a kitchen

stool painted white, height 50 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

conventions" (dmd, 48). This appeal to mechanical drawing is intended as an alternative to pictorial conventions, since the technical and schematic aspects of the industrial prototype appear to escape artistic considerations. In choosing actual objects as ready-mades, however, Duchamp extends the notion of "mechanical drawing" to include the objects themselves rather than their models (design prototypes). In making this dramatic leap over the figurative into the literal, Duchamp disrupts the logic of representation that defines both technology and art. Instead of representation, that is, a presentation that conforms to and confirms something previously given, Duchamp resorts to a mode of literal presentation that undermines the "idea" of the object as a representation. As Masheck observes, the ready-made enables Duchamp to "reduce representation to the amusing redundancy of each object fully representing itself both as a unique entity and as a representative of some class of objects."[46] While Masheck understands Duchamp's move as an effort to outwit Cubism, without resorting to abstraction, one should note that Duchamp's true wit lies in his rediscovery of the object as a pun.

Duchamp's intervention consists not in the artisanal production of ready-mades but rather in the intellectual intervention of their selection, naming, and display. The Bicycle Wheel (Roue de bicyclette; 1964 version [original version of 1913, lost]) (fig. 40) is displayed with the fork upside down, screwed to a kitchen stool. The Bottle Rack, the snow shovel in In Advance of the Broken Arm, and the Hat Rack are hung from the ceiling, whereas the coat rack called Trap is nailed to the floor instead of the wall, its usual place. This rotation or reversibility on the object's functional place draws attention to the creation of its artistic meaning by the choice of the setting and position ascribed to the object. The meaning of the ready-made seems to lie less in its objective status than in the shifts in position that qualify its potential as work of art or non-art. The ready-made is not merely an art object on display but one that displays the constitution of the objective character of art. The ready-mades thus emerge as the paradoxical symptoms of an age obsessed with materialism, but unable to account for the conventions defining materiality.

Commenting on Duchamp's Bicycle Wheel, Jack Burnham notes the punning displacements that this work operates on both the utilitarian and artistic domains:

While beautiful in itself, the utilitarian wheel has been rendered functionally immobile—like a turtle on its back. It is motion that goes nowhere and a machine that does not "work" in the accepted sense. Yet, by aesthetic inversion, Duchamp has transformed the wheel into an optical device. As in the glass paintings that he was shortly to create, the viewer was given the option of looking through the moving wheel or catching the reflective patterns of its glinting spokes.[47]

As Burnham suggests, Duchamp alludes to the utilitarian and mobile function of the bicycle only to suspend this usage by recovering it in the service of optics. An instance of kinetic art, the moving wheel is transformed into an optical device. Duchamp harnesses the mechanical aspects of the moving wheel, discovering a plastic potential, in the transparency of the spokes or mirrorlike reflective surface.[48] The rotational movement of the bicycle wheel also suggests links between optical properties and verbal puns. Consequently, Burnham's claim regarding Duchamp's "aesthetic inversion" should not be understood as a concession to optics, and hence, as the recovery of the ready-made into the artistic domain. Instead, as this discussion will demonstrate, Duchamp uncovers in the mechanical rotation of the bicycle wheel, a plastic dimension, including reversibility, as well as inversion. Considered in these terms, the bicycle wheel emerges as a switch or a faucet, a mechanical device whose artistic significance may be turned on or off at will, like a pun.

Duchamp recognizes that his interest in movement is an extension of his earlier pictorial explorations: "Again, the idea of movement, you see just transferred from the Nude into a bicycle wheel, at the same time I was working on The Glass."[49] Yet the movement in question here is not linear, since the diagrammatic arrows marking the progression of movement in the Nude describe a set of rotations. Rather than functioning as simple deictical markers that designate something by pointing at it, these arrows outline a circular movement, so that they point back upon themselves. Asked by Cabanne whether the arrow has a symbolic significance, Duchamp responds: "None at all. Unless that which consists in introducing slightly new methods into painting. It was a sort of loophole. You know, I've always felt this need to escape myself." (DMD , 31). The dia-

gramatic arrow is defined as a "loophole," that is, as a loop whose figurative "turn" outlines a double strategy: the movement away from the conventions of painting is simultaneously an evasive ploy that turns back on itself, since it also implies coming to terms with pictorial traditions.

While the functional utility of the bicycle wheel has been suspended, its ability as a ready-made to generate "work" of a cognitive nature is being elaborated. The bicycle wheel can be seen as a machine that generates verbal, as well as optical and kinetic effects. The rotation of the arrows in Duchamp's pictorial experiments is literally embodied in the rotation and reversibility of the spokes of the bicycle wheel. The Bicycle Wheel recalls Duchamp's other mechanical analogy for puns Door: 11, rue Larrey (Porte: 11, rue Larrey; 1927) (see fig. 78, p. 214), a door that Duchamp built in such a way that its rotation around a hinge opens one doorway as it closes another. This door thus represents a logical conundrum, since it is paradoxically open and closed at the same time. The door is an allusion to the Bicycle Wheel, to the extent that they both function as machines whose motion generates multiple effects. The bicycle wheel and the door emerge as mechanical analogues for the kinetic, optical, and reiterative structure of puns. Duchamp's subsequent experiments with rotation and puns, in Project for the Rotary Demisphere (1924), Discs Inscribed with Puns (1926), Anemic Cinema (Anémic Cinéma; 1925–26), and Rotoreliefs (optical discs) (1935), demonstrate his continued efforts to elaborate puns as devices, whose rotation and reversibility ("mirrorical return") suspend and unhinge meaning.[50]

If the bicycle wheel documents Duchamp's fascination with movement as a way of distancing himself through kinetics from pictorial optics (albeit in a roundabout way), his ready-made Comb (Peigne; 1916) (fig. 41), a gray steel comb bearing an autograph inscription on its edge, appears at

Fig. 41

Marcel Duchamp, Comb (Peigne), 1916. Ready-made: gray steel comb, 1 1/4 x 6 1/2 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

first glance to be a return to a more static and thus conventional position. However, the static quality of this steel, or rather "still," comb is disrupted once we consider its title. Comb (peigne, in French) refers not to the infinitive to paint but instead to the French subjunctive form of painting, que je peigne (translated from French as "if I could only paint" or as "I should or ought to paint"). These tentative formulations capture the necessity of painting as a conditional, rather than as a given or selfevident activity. What then explains Duchamp's hesitancy or reluctance to resort to or engage in painting, in the first place? Duchamp's reproduction of the Comb on the cover of the journal Transition (New York, 1937, no. 26) alerts the viewer to the "transitional" status of this ready-made, yet the question persists as to what kind of "transition" Duchamp may have had in mind. A joking comment by James Joyce to Sylvia Beach that "the comb with thick teeth shown on this cover was the one used to comb out Work in Progress," reveals the figurative and artistic potential of the comb as a brush: a figurative instrument for combing through a text, but also an instrument that makes representation possible, like a painter's brush.[51]

While these observations highlight the figurative and pictorial potential of the comb, they do not as yet illuminate decisively Duchamp's use of the comb as a commentary on painting. The enigmatic inscription on the edge of the comb provides further clues toward elucidating his position: "3 OU 4 GOUTTES DE HAUTEUR N'ONT RIEN A FAIRE AVEC LA SAUVAGERIE" (3 OR 4 DROPS OF HEIGHT HAVE NOTHING TO DO WITH SAVAGERY). Once we consider this inscription in terms of its punning character, we begin to have an insight into its potential meanings. "3 OU 4 GOUTTES DE HAUTEUR" read phonetically generates "3 OU 4 GOUTTES D'ODEUR" (3 OR 4 DROPS OF ODOR), an expression that appears equally meaningless unless we consider it in light of Duchamp's condemnation of painting in terms of both the "splashing of paint" and the "intoxication of turpentine." The expression A FAIRE (to do) may also be translated as making or creating; however, it can also be read as a pun on a business transaction (affaire), or as something made of iron (un fer ). This double pun on faire as fer may seem gratuitous, were it not the very formulation that Duchamp employs when he was asked to define genius "Impossibilité du fer" (the impossibility of iron), which can also mean the impossibility of making

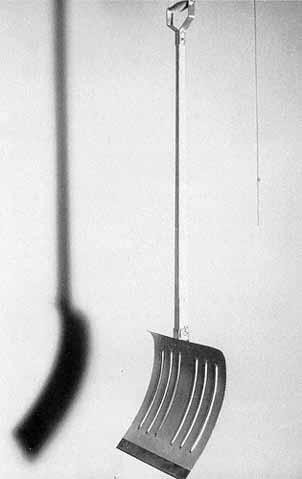

Fig. 42.

Marcel Duchamp, in Advance of the Broken Arm (En avance

du Bras Cassé), 1964 (original version of 1915, lost). Ready-made:

wood and galvanized iron snow shovel, height 52 in. Yale

University Art Gallery, gift of Katherine S. Dreier to the

Collection Société Anonyme. Courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

(faire )[52] Savagery (sauvagerie ) is a figurative expression for designating unsociable, uncultured, or unsavory behavior. Now we begin to understand that Duchamp's punning inscription on the comb may refer to the iron (y) of his position as an artist who abandons one form of creativity, that of making paintings (which he associates with savagery of the splash and odor of paint), in order to adopt another form of making, which is conceptual rather than artistic in the traditional sense. The ready-made embodies this new form of non- or an-artistic making, since it involves intellectual, rather than manual work.

If this inference seems a little farfetched, it is possible to confirm it by rapidly examining other ready-mades: the bottle rack, Bottle Dryer (1914), and the snow shovel, In Advance of the Broken Arm (En avance du bras cassé; 1964 version [original version of 1915, lost]) (fig. 42), both articles made of galvanized iron and suspended in the air. In the previous

discussion on puns the bottle rack was examined as a mechanical analogue of linguistic puns. The function of this object as a bottle dryer, however, makes one wonder whether this object is intended as an example of "dry art," that is, as yet another instance of Duchamp's rejection of painting (which he associates with the wetness of paint). The snow shovel is also an example of "dry art" to the extent that the liquidity of water must crystallize into snow (a solid, dry powder) in order to be shoveled. The snow shovel (pelle à neige) begins to make sense, once one literally spells out (épeler ) its punning associations. Shovel (pelle, in French), which means scoop or blade, can also be used to signify dustpan (pelle à poussière) or a fall off of a bicycle. One only has to recall Man Ray's and Duchamp's photograph Dust Breeding —a picture of the Large Glass lying flat and showing the accumulation of dust—to realize Duchamp's leap from the colorless snow to the insignificant grayness of dust. Like Leonardo before him, who recognized the plastic and temporal potential of dust since he saw in its reliefs a miniature terrain and also recommended using it as a device for measuring time, so, too, does Duchamp begin to breed dust.[53] Mimicking his affection for "gray matter," or "brain facts," the dust becomes both a symptom of the temporal erosion

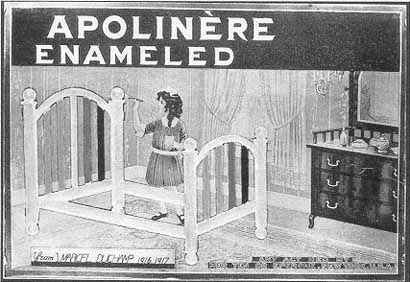

Fig. 43

Marcel Duchamp, Apolinère Enameled, 1916–17. Ready-made: cardboard and

painted tin advertisement for Sapolin brand of enamels, 9 5/8 x 13 3/8 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

of the traditions of painting (its "gathering dust") and, paradoxically, a statement about the conceptual future made visible by this very decline.[54] If painting implies being in the "color" business, Duchamp demonstrates that he will have no hand in it. Is it then surprising that the snow shovel is entitled In Advance of the Broken Arm?

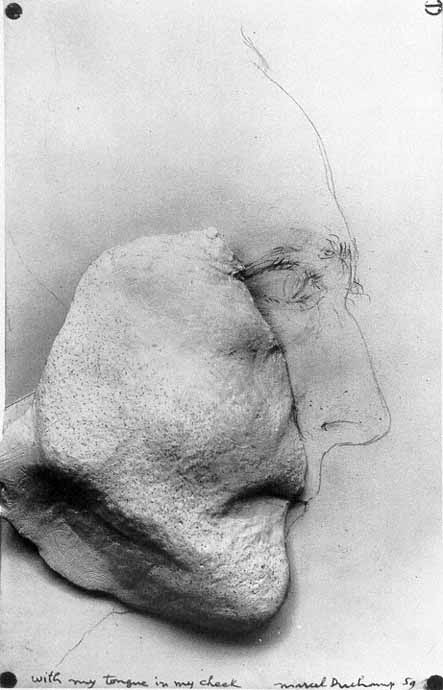

But if Duchamp will have no hand in painting, does that mean that he stops making art altogether? Or does it mean that someone else picks up the relay, another person, or perhaps, another persona? In order to examine these questions, we turn to another of Duchamp's ready-mades, Apolinèere Enameled (1916–17) (fig. 43), a cardboard and painted tin advertisement for the Sapolin brand of enamels. Duchamp alters this advertisement by covering some letters in black paint and adding in new letters, so that "Sapolin Enamel" became "Apolinèere Enameled." By drawing a reflection of the girl's hair (in pencil) in the mirror above the chest of drawers, he adds new visual details to the original image. Moreover, he transforms the commercial slogan, printed on the bottom right-hand side of the image, into what appears to be a nonsensical message: "Any act red by her ten or epergne." Carol P. James interprets this complicated visual and linguistic rebus as the scene of a narration, which Duchamp renarrates to his own ends:

The scene of the little girl who wields a paint brush as she would her comb (her hair, sketched in by Duchamp, is reflected in a mirror), as a practical gesture, is a sort of allegory of the ready-made where artists who paint ("peignent") give up their brushes to choose everyday objects like the comb ("peigne").[55]

James's remarks correctly identify this scene as an allegorical reflection on Duchamp's dilemma as an artist who gives up the traditional means of painting (the brush), in favor of conceptual and poetic tools embodied in the ready-made as a pun. Instead of representing (enameling or embellishing) by using paints, Duchamp chooses to depict not by using colors but by resorting to poetic forms of expression. Hence the title of this work, Apolinère Enameled, is a pun on the name of the poet Guillaume ApolliNaire (1880–1918).

But why would Duchamp choose to represent his own dilemmas as an

artist seeking to question the limits of art, in the form of a little girl wielding a brush? By drawing in the girl's "hair" as a reflection in the mirror, Duchamp literally designates her legacy as an "heir." "Heir" is, however, also a pun on the French pronunciation of the letter "r" (air, ) which in English is pronounced as "arh" (the same as art, in French). This pun on art is a reference to another ready-made, Paris Air (fig. 44), a glass ampule accompanied by a printed label "Serum Physiologique." Serum is a yellowish, clear, watery fluid drawn from blood that has been made immune through inoculation.[56] The punning analogies of air and art reveal the fact that the heir to painting may be engaged in a bloodless, or rather, a colorless task. The inscription on the right-hand bottom, "Any act red by her ten or epergne," now becomes less enigmatic, since it stages allusions to the color (red), to reading "any act red" and to painting (the comb, peigne, as a pun on epergne). Epergne can also be read as a pun on thrift or savings (épargne , in French), thereby suggesting that painting may be kept at bay, or safeguarded against itself, through its read (red) or ready-made embodiment as a pun.

Given Duchamp's critique of ocular (oculiste ) art, it is not surprising that this image, which depicts a little girl painting, also functions as a pun on Duchamp's own legacy, an immunity to painting guaranteed through in(ocul)ation. The signature "[from] Marcel Duchamp 1916–1917" designates the gesture of authorship both as an issue (coming from someone and issued to someone else) and as a temporal interval, a space that shatters the self-identity of authorship through circulation. This signature no longer designates Duchamp, but rather his displacement as an authorial persona. Rather than functioning simply as a postcard (an item circulated through the mail, also a pun on male), this work marks both the displacement of the authority of painting and its future reissue (its post, or future legacy) as the impossibility of art.[57] Thierry de Duve's comments regarding Duchamp's painting, The PASSAGE from the Virgin to the Bride, anticipate the paradoxes that are explicitly spelled out in Apolinère Enameled: "Marcel Duchamp, painter, signs the impossibility of painting while Rrose Sélavy, artist, depicts (dépeint ) art's possibility. Unless what happens is really that the anartist Marcel Duchamp designates the possibility of painting while the nonpainter Rrose Sélavy paints the impossibility of art."[58] The issue, however, is less one of deciding who exactly (Marcel or

Fig. 44.

Marcel Duchamp, Paris Air (Air De Paris), 1919. Readymade: glass ampule, height 514 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

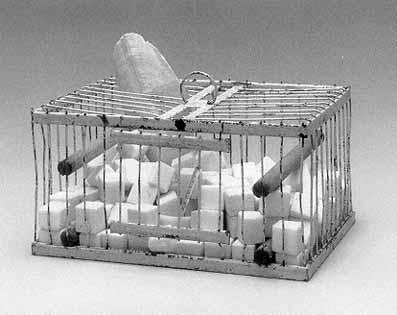

Fig. 45.

Marcel Duchamp, "Why Not Sneeze Rrose Sélavy'," 1921 Semi-ready-made: 152

marble cubes with thermometer and cuttlebone in small birdcage, 4 1/2 x 8 5/8 x 6 1/4 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

Rrose) depicts the possibility or impossibility of painting or art, but rather the fact that these positions act as mechanical relays that may be switched on or off, like puns. As our subsequent discussion will show, the reversibility of these positions can only be understood by conceiving them according to the poetic and thus reversible logic of puns, as instances of "mirrorical return."

Duchamp's gestures embody a logical impossibility, since affirmation and denial, past and future, male and female coexist within Apolinère Enameled. But this very coexistence shatters the identity of the artist, who now embodies not only different positions, but also differently gendered personas—Marcel Duchamp and the little girl. Heralding the appearance of Duchamp's artistic alter ego Rrose Sélavy, this little girl is not someone to be taken lightly or even sneezed at. After all, she will go on to sign and thus authorize Duchamp's semi-ready-made, "Why Not Sneeze Rrose Sélavy?" (1921) (fig. 45), a birdcage filled with marble cubes in the shape of sugar lumps with a thermometer and cuttlebone. The cuttlebone is a fig-

urative expression for commerce (the cuttlebone of commerce) and thus an indicator of Duchamp's particular dealings (affairs) with both painting and the notion of authorship. This work, like Apolinère Enameled, suggests that authorship is not fixed referentially, since it cannot be contained by the identity of the artist. Considered in these terms, authorship emerges as a process of engenderment, a commercial and erotic affair, which sets the author into motion as a relay of personas, thereby delaying, and thus postponing, the author or artist from attaining a proper or fixed identity.

Ready-Made Ironies

Humor and laughter. . . . are may pet tools.

— Marcel Duchamp

I act like an artist although I'am not one.

— Marcel Duchamp

The previous discussion of ready-mades begins to outline something in the order of a paradox. While the ready-made is chosen according to visual indifference and its lack of aesthetic qualities, the punning associations engendered by its title appear to play an extremely significant, if not a determining role. When asked by Francis Roberts to explain how he chooses a ready-made, Duchamp disarmingly replies:

It chooses you, so to speak. If your choice enters into it, then, taste is involved, bad taste, good taste, uninteresting taste. Taste is the enemy of art, A-R-T. The idea was to find an object that had no attraction whatsoever from the aesthetic angle. This was not the act of an artist, but of a non-artist, an artisan if you will. I wanted to change the status of the artist or at least to change the norms used for defining an artist. Again to de-deify him. The Greeks and the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries thought of him as a worker, an artisan.[59]

Duchamp's disclaimer regarding his choice of the ready-made is qualified by the proposition that the ready-made chooses him. If the choice of the ready-made poses a problem, this is because it involves the notion of taste—be it good, bad, or indifferent. By refusing the attraction of the aesthetic qualities of the object, Duchamp attempts to resist the appropriative powers of taste, whose normative strictures are enforced through a process of repetition that precludes invention. By questioning the definition of art and the artist, Duchamp demystifies ("de-deifies") the endeavor

and the position of those involved in the production of artworks. By comparing himself to an artisan, Duchamp redefines the notion of artistic creativity as a skill, craft, or trade: a process of production based on literal reproduction and execution.

As the ready-mades have demonstrated, however, Duchamp's artisanal intervention is not manual but intellectual. While rejecting a visual engagement with the object, since this premise has been one of the unquestioned givens (or "ready-mades") of art, Duchamp resorts to another kind of "making," one that draws on the craft of wit, understood as wisdom or sagacity. This appeal to intellectual activity is not idealistic but humorous, insofar as it erases the distinctions between objects and their names by treating them both as signifying mechanisms or puns. Resorting to ordinary objects, Duchamp discovers that their materiality is no more solid than the materiality of the linguistic and philosophical conventions that constitute them. While abstaining from "making" objects in the visual, aesthetic sense, Duchamp engages in a process of making, which both unmakes and reshapes the boundaries of the objective world and the position of the artist.

When asked by Francis Roberts whether he thought of himself as being "antiart," Duchamp corrected him:

No, no the word "anti" annoys me a little, because whether you are anti or for, it's two sides of the same thing. And I would like to be completely—I don't know what you say—nonexistent, instead of being for or against . . . . The idea of the artist as a sort of superman is comparatively recent. This I was going against. In fact, since I've stopped my artistic activity, I feel that I'm against this attitude of reverence the world has. Art, etymologically speaking, means to "make." Everybody is making, not only artists, and maybe in coming centuries there will be a making without the noticing.[60]

This resistance to being labeled "antiart" reflects Duchamp's understanding that an aesthetics of negation may not be different from an aesthetics of affirmation. To be for or against something means simply to maintain a position within the framework of art as a preestablished paradigm. His attack on the idea of the artist as "superman" reflects his rejection of

nineteenth-century ideology, which equates the creative act with an act of will. Duchamp defines the creative act as a "difference between the intention and its realization" (WMD, 139); that is, as a critique of the identity of the creative subject, as well as the objectification of the creative act. In the wake of Nietzsche's critique of representation, Duchamp redefines art as "the making without the noticing." But what kind of making and maker does this statement involve?

Duchamp's enigmatic pronouncement in The Box of 1914, a set of puns whose rationale revolves around the devaluation of art and its feminine reengenderment, enables us to understand the philosophical implications of his treatment of ready-mades as puns:

arrhe is to art as

shitte is to shit

arrhe/art = shitte/shit

grammatically :

the arrhe of painting is feminine in gender. (WMD, 24)

These proportional fractions summarize in a graphic fashion Duchamp's transformation of art and its relation to value for modernity. In one of the notes to The Green Box entitled "Algebraic Comparison," Duchamp resorts to similar ratios, while clarifying this formulation by indicating that the term above the bar is a ("being the exposition") and the term below is b ("the possibilities") (WMD, 28). This indication alerts the viewer to the fact that the rationale of these ratios is not to be found in mathematics but in poetry: "the sign of ratio which separated them remains (sign of the accordance or rather of . . . look for it )" (WMD, 28).

At first sight, Duchamp's punning analogy amounts to a scatological joke: art is like, or is, shit, insofar as it does not possess any inherent value. This rapid analogy between art and excrement, however, breaks down the

moment that one takes a closer look at Duchamp's formulation. His analogy of arrhe/art and shitte/shit is not based on the equation or comparison of these puns but rather reflects the internal dissemblance of these terms insofar as they are puns. The problem is that the identity of both of these terms is destabilized through their punning representations: they sound phonetically alike, but are graphically different. Duchamp's humorous formulation thus captures the tendentious reach of logic, whose pet tools—analogy and identity—are upstaged by the poetic implosion of puns.

In the case of Alfred Jarry's (1873–1907) Ubu roi (1896), it is exactly the difference between shitte/shit (merdre/merde ) that allowed him to pass off his play as an aesthetic exercise, despite the vocal protestations of an audience threatening to riot. This poetic infraction that fails to be punished as aesthetic contraband establishes a pattern by which nonsense emerges as a gesture beyond contestation or negation. The analogical relation of arrhe/art and shitte/shit is undermined through nonsense. Hence the incapacity of these signs to generate value; for value presupposes the equivalence of two terms through reference to a common standard, so that a sign can stand in for something else.[61] In the examples above, however, the phonetic reiteration of arrhe/art annuls these terms through its mirrorical reversibility or implosion. Rather than generating meaning, this phonetic reproduction annuls its very possibility.[62]

The punning equivalence of arrhelart = shitte/shit is reduced to a statement about duration, an inscription of temporality into the logic of similitude:

= in each fraction of duration (?) all/future and antecedent fractions are reproduced—

All these past and future fractions/ thus coexist in a present which is/ really no longer what one usually calls/ the instant present, but sort of/ present of multiple extensions—/ See Nietzsche's eternal Return, neurasthenic/ form of a/ repetition in succession to infinity. (Notes, 135)

Duchamp's note on The Large Glass makes it possible to understand how repetition generates temporality, rather than identity. Duration, in this case, is not defined linearly, since past and future fractions coexist in a "present

of multiple extensions." This fractioning of appearance expands the present to an interval that no longer corresponds to its traditional reduction to an instant. Duchamp's reference to Nietzsche's "eternal Return" as a "neurasthenic form of a repetition" highlights the paradox of the logic of appearance. For Nietzsche, as for Duchamp, the notion of return is crucial, insofar as all appearance is re-presentation, that is, a return as appearance."[63] That which appears, or manifests itself, returns as representation. The ready-made may be considered as an instance of the "eternal Return" to the extent that it signifies, not the return of the sameness or identity of things (the thing itself) but instead of their appearance—the manner and mode through which things show themselves. The triumph of appearance in this context becomes the stage for the "show" of representation, Thus the attempt to represent leads not to identification but rather to the expenditure of the notion of signification through puns.[64]