2—

The Trials of Discipleship:

Le Roman de la poire and Le Dit de la panthère d'amours

It is because things are remote from you, filtered through books and hearsay, that you feel you have to dress them up, make metaphors . . . you have renounced the flesh, but you do not renounce the thought of the flesh and, since you are a man of words, you enjoy it more avidly at second hand.

Julia O'Faolain, Women in the Wall

In an intellectual and literary world so strongly shaped by the dynamics of mastery, the disciple emerges as the focus of particular attention. However visible the master is in French medieval culture, he remains an exceptional figure. He is part of an elite. Within the clerical caste, the university community, or the lay milieu of the thirteenth-century and fourteenth-century didactic narrative we have studied, he represents a minority.[1] The disciple, by contrast, is a popular persona. His story of immature, well-intentioned efforts is accessible and generalizable in a way his mentor's is not. His trajectory is meant to be Everyman's, one that illustrates the travails of becoming a masterful man. Moreover, it is through him that mastery in its two senses is transacted. Behind every magister in vernacular narrative stands an untested disciple. In fact, given the custom of calling a poet maistres , there is a way in which many narratives modeled on the Roman de la rose dramatize the career of the master and the process by which the disciple grows into the magister role occupied by the author. The fascination with the operations of mastery is thus cultivated by narrating again and again the story of the novice.

As numerous allegories recount that story, it involves student-narrators who apply the lessons of the master, this time the magister amoris (the

master of love.) Youthful and hardworking, these disciple figures are engaged in a characteristic twofold struggle: the need to debate with the master so as to prove their own competence and the challenge of reproducing his authoritative knowledge about women. From didactic to allegorical narrative, the shift is from representations of a doctrine to those of a discipline, from the laying out of precepts concerning "a woman's nature" to the practice of that learning. The disciple's goal of mastering such knowledge remains structured by the scholastic disputation. In the standard configuration, the bachelor took the role of the respondens or responsalis (respondent) and debated with the master as well as with the opponens , the opposing figure.[2] From the position of respondent, the disciple could articulate his version of the master's knowledge and establish his intellectual prowess. Ideally, such prowess would also signal his autonomy. His performance in a disputation was meant to sanction his eventual rise to mastery. The paradox was that his own mastery was by no means assured. The act of disputing disclosed the disciple's difficulties in making the master's role his own—difficulties often represented in terms of the disciple's inherent weakness. As the Roman de la rose describes the disciple's predicament, "The master wastes all his effort when the disciple who listens to him does not put his heart into retaining all that he should remember" (Li mestres pert sa poine toute quant li deciples qui escoute ne met son cuer el retenir si qu'il l'en pulse sovenir; lines 2051–54).

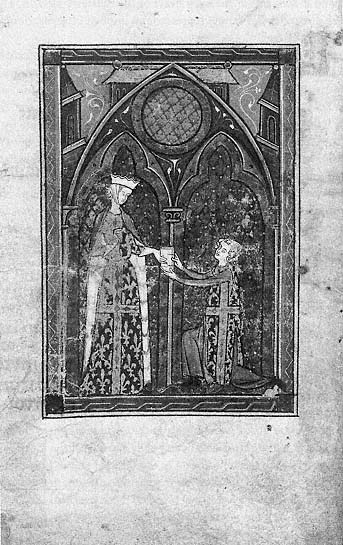

This image of the faltering disciple comes into clearer focus when we recall the specifically submissive quality of his relations with the master. In the scholastic domain, submissiveness was the necessary rite of passage leading to the practice of mastery, but it carried with it the danger of indefinite subordination. It suggested the possibility that the disciple might never graduate to the powerful role of magister , lingering instead in a limbo of lost opportunity and underachievement. In a vernacular context where the disciple's search for mastery was directed toward women, this possibility was all the more apparent. No matter how vigorous his efforts to translate his submissiveness to a lady into ultimate command over her, this masterly goal might never be realized. Projecting a lady as magistra did not systematically insure the disciple's ultimate authority as Andreas Capellanus had intended. Like the figure in this miniature from the Roman de la poire , he might be caught in a posture of obeisance, unable to exercise his control, incapable of approaching a woman any other way (Figure 5).[3]

The role of discipleship points up deficiencies in the structure of masterful relations. As we saw in chapter 1, masters can be depicted as precarious figures; the faltering disciple adds one more blow to an already

5. The writer in training offers his book to the lady. Le Roman de

la poire .

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, f.fr. 2186, fol. 10 verso.

Photograph, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

shaky structure of authority. His characteristic insecurity—"his not taking heart"—is further evidence of the instability of the system of mastery as a whole. Moreover, through the faltering disciple figure we can detect the uneven pattern of symbolic domination laid down by the discourses of mastery. His story calls into question the logic of mastering the subject of

women and it does this at the very heart of the masterly system. The figure of the disciple under duress represents an implicit interrogation of that system from within.

In order to see what that interrogation entails, I shall concentrate here à titre d'exemple on two allegories exemplifying the disciple's predicament. The late-thirteenth-century Roman de la poire and the early-fourteenth-century Dit de la panthère d'amours depict the initiation of the disciple through letter writing.[4] Both texts build on the Roman de la rose by combining the disputational model with the common pedagogical genre of the ars dictaminis (the art of correspondence).[5] Their account of the disciple's efforts to compose a letter for a woman is thus designed as a school exercise. This exercise turns out to be an ordeal for the disciple. It is so fraught with problems that it provokes a condition in him far worse than the ill-preparedness of the Rose narrator. Fear, paranoia, a full-fledged panic attack: all these allegorical "states of mind" reveal a disciple on trial. By tracing out these various trials one by one, we shall discern more clearly the limits of discipleship.

A Trying Discipline

Like all neophytes in the clerical milieu, these two disciple-narrators begin from a position of real insecurity. Without the instructions of the master, they are tentative about their assignment of addressing a woman. Such uncertainty is the first symptom of the disciples' trouble in putting the master's knowledge about women into action. And it takes two forms. On the one hand, it highlights the difficulty they have with the art of writing that forms part of the master's craft. On the other, it shows how that difficulty increases significantly when their writing is directed toward women. That disciples cannot write easily is proof of their youthful inexperience; that they cannot write to women illustrates the charged relation the clerical domain has posited between women and textualized learning.

In the Poire , the disciple tackles his difficulty in writing alphabetically. Reciting his ABCs provides one reassuring starting point: "Amors qui par A se commence" (line 1). The Poire uses the favorite medieval ploy of an acrostic as a way to regulate the disciple's unease. It represents the disciple beginning to make sense of his writing exercise by working with its mechanics—by practicing the individual letters B, C , and so on. This letter game becomes, in effect, a field in which the disciple tests his developing skills.[6] It is a medium of his potential mastery. Yet if this acrostic promises a type of intellectual mastery in relation to the woman correspondent, at

the same time it shows just how far the disciple-narrator must go to achieve it. It continues to reveal his trouble. His ongoing difficulty comes through in the extended letter game that follows—a narrative ABC of exemplary lovers telling their stories. This sequence spells out how the disciple-narrator should proceed. Cligés, Tristan, and Paris, in the role of master, all instruct him in their individual lessons. Through their examples the disciple is brought to articulate his own story:

Ge, qui m'en entremet, en sui bien assenez.

Cuer et pensee i met, et tant me sui penez

que s'amor me pramet ma dame, buer fui nez!

(lines 82–84)

I, who undertake this, am well supported. I put both heart and mind into this, and took such pains that I am promised the love of my lady. I am born lucky!

Wedged in between the testimonials of famous lovers is the account of the disciple's birth. He is represented narrating how he becomes an amorous subject. This narration evokes the process by which the disciple strives to establish his separateness vis-à-vis the master. Saying "I" is a crucial step in this process, because it moves beyond mere recitation of the master's words. It marks a major attempt at controlling his chronic insecurity and adapting the master's lessons himself. What has still to come, though, is the disciple's birth as a writing subject: will he be able to write masterfully about love to his woman reader?

That is why his difficulty over beginning persists. Through a second acrostic starting with the letter A , the Poire disciple speculates about the purpose of his writing exercise. And his speculation gets to the core of his relation to a master. As we have seen in those didactic narratives called enseignements , a chief goal of the disciple's disputation with the master is knowledge about women. Yet the Poire disciple admits his ignorance: "I am in no way learned" (ge ne sui mie gramment sages; line 368). Untrained, inexperienced, he appears unfit to write authoritatively. Out of this ignorance, however, the disciple forges another "obscure way" toward knowledge and autonomy (lines 342, 366).[7] As in Lorris's Rose , subjective experience comes to play a role in the disciple's formation. However unreliable that experiential way, it ranks with any textual knowledge the master can transmit to him. This comparison is, of course, misleading insofar as the notion of subjective experience is never pure or free of outside influences. No disciple can ever begin as a solo agent. Nor will he ever be rid of his masters. His subjective experience is always a cumulative affair—the sum of his interaction with others. The second acrostic makes this

clear: it heralds another beginning of the Poire with a well-known lyric quotation.[8] In other words, the disciple conceives of his own knowledge through the voice of others. His coming into learning involves a variety of masterful material, all filtered through his experience. In doing battle with his uncertainties, the disciple is thus shown to articulate what are echoes of the master's authoritative voice.

While the disciple's insecurity complex about women makes a zigzag of the Poire 's beginning, in the Panthère it disrupts the narrative as a whole. The trope of not daring prevails. From the outset, when "he does not dare to write the name of his lady," the narrator is struck dumb (cilz qui son dous nom n'ose ecrire; line 3). The courtly topos of discretion is exaggerated to the extreme. This fearfulness correlates with the disciple's fundamental instability. His first thought is one of incapacity; instead of aspiring to action he broods over the little he can do at all. The structure of the Panthère foregrounds this problem of the resourceless disciple. By duplicating the stock device of the dream, it shows him to be doubly desperate for the understanding an allegorical vision should offer. Because he cannot fathom the fantastical bestiary landscape of the first dream, another is required. And the second dream imaging the lady is built into the first. This Chinese-box effect accentuates the helplessness of the Panthère disciplenarrator. The closer he draws to seeing the woman, the more disjointed his dreams appear. There is little sign of the disciple having learned anything. On the level of textual construction, this resourcelessness creates an aimless quality to the Panthère . We have the impression of reading a work that turns in on itself with no objective clearly in view. Such narrative disarray betrays the disciple's profound malaise over writing masterfully.

In keeping with the Panthère's mise en abyme style, the only element that can dispel the disciple's malaise is the dit itself. Enclosed within the Dit de la panthère are what we can call drafts of dits —rough versions:

Que je par amors lor deïsse

Ma volent?é, et descouvrisse

Se de riens estoit ma pensee

En loiaus amors assenee.

Je leur dis c'un dit fait avoie,

Ou ma volenté demonstroie,

Si commençai le dit a dire

Si com vous poez oïr lire.

(lines 817–24)

Out of love, I owe it to them [various allegorical figures] to share my will and reveal that my thought has been all taken over by loyal love. I say to them that had I made a dit , I would show my desire. So I'll begin to speak the dit as you can hear it read.

However haltingly, the Panthère disciple gives voice to his doubts. Such an admission allows him to open up. It triggers a kind of self-reflection. As Jacqueline Cerquiglini-Toulet has argued persuasively, the dit involves an internalized debate based on subjective experience.[9] And such a debate provides not only a means of self-disclosure but also of a progressive steadying of the self. His dit is replete with phrases such as ouvrir, descouvrir, dire apertement , expressions that accentuate the effort to become articulate. At this early stage, the disciple is working to come into his own.

In this internalized debate we should recognize a version of the disputation. What is habitually conducted in a public forum is, in these two narratives, moved within the figure of the disciple himself. Yet this move does not entail leaving the master behind. He remains implicitly present. As we have already seen, his knowledge is refracted through the multiple voices the disciple assumes. The master's disputation is thus integrated into the flow of the disciple's inner musings. The familiar pattern of the master talking through the disciple intensifies.

The prospect of actually approaching the woman brings this disputatiousness out. Faced with a woman reader, the disciple experiences a type of clerical psychomachia whereby he disputes with various authoritative voices. In the Poire , this debate begins just as he broaches the subject of women. An unidentified interlocutor intervenes, and the ensuing dialogue takes the well-known pedagogical form of question and answer (quaestio et responsio; line 372). For every point the Poire disciple narrator advances, he is challenged by an opposing one. Nothing is left uncontested, especially his claim that love is an oxymoron:

Max et biens, ce sunt .II. contraire,

et vos lé metez en commun

autresin con s'il fussent un!

Ce n'est pas reison ne droiture;

qui les juge selonc nature,

ge n'i voi point d'acordement.

Vos nos devez dire comment

s'acorde l'une et l'autre part.

(lines 507–14)

Bad and good, these are two contraries and you put them together as if they were one! This doesn't make sense; it isn't right. If you judge them according to their nature, I don't see any compatibility at all. You ought to tell us how one is compatible with the other.

This mock disputation invokes the criteria of contraries that shape so much of medieval logical thinking.[10] Can the disciple work through the contrary, defined in logic by its very difference and irreconcilability?[11] Can

he account for the irreconcilable? On the face of things, he and the masterly figure dispute love as it is emblematized by the bittersweet pear of the narrative's title. But in the context of the narrative, that pear is doubtless a cipher for women: master and disciple are in fact arguing over the contrariness of women.[12] Poised on the threshold of addressing one woman reader, the disciple is pressed to explain what it is the general class of women represents for him. And his explanation is structured in the characteristic terms of masterful knowledge. Such a debate over "contraries" is part of a scholastic epistemological model that abstracts women. It plots them on a grid that defines them—this time—according to their oppositional difference.[13] In arguing along these lines, the Poire disciple-narrator begins to prove his competence in conventional scholastic reasoning. Yet by the same token, the disciple's disputing of women as contraries suggests his difficulty in making sense of them. Insofar as contraries represent what is different or irreconcilable, "contrary" women exemplify the disciple's trial in approaching the one woman reader. There is a critical discrepancy between his understanding and her existence. No matter how thoroughly the disputation with the master analyzes this discrepancy, it is never completely resolved. The idea of contrary women remains a persistent conundrum—a sign of the disciple's limited understanding.

Those limits are more sharply delineated in the Panthère , where the timorous narrator cannot even rise to the challenge of a disputation. Representing an earlier, green phase in development, this disciple "does not dare" to argue with so many masterly voices, but seeks instead their instruction:

Si fu en grant merancolie,

Comment aucun trouver porroie

Qui de ce que veü avoie

Me deïst la significance. . . .

Car j'avoie grant apetit

Et grant desirrier de savoir

Se par l'un d'eulz porroie avoir

La droite interpretation.

(lines 148–51, 200–203)

So I was in a deep melancholy. How was I to find someone who would give me the significance of what I had seen? . . . For I have an enormous appetite and great desire to know, if I could have the right interpretation by one of them [a company that he sees].

Melancholia is the mark of the absent master. And the only way to cure it involves having "the right interpretation" of women. Notice the distinc-

tion here: this is not the usual masterly drive to know, or even the disciple's penchant for debating as a way to test his new-found knowledge. Instead, the Panthère narrator searches for a set rule by which all phenomena can be interpreted correctly. The disputational process is reduced to an elementary and largely passive ritual whereby the disciple need only assimilate the various precepts concerning women that a master hands down to him. There are many. Following the example of Jean de Meun, the narrative sets out an encyclopedic variety recapitulating much contemporaneous literature. Allusions to the Roman de la rose and to Drouart La Vache's translation of the De amore , invocations of the poet Adam de la Halle's songs, long passages from lapidaries: all this represents the essential curriculum that a master passes on to a needy disciple.

Given such a program of instruction, the Panthère takes on the character of a clerical lecture (lectio ), with its many participants.[14] The figures of the God of Love and Venus are certainly familiar from the Rose , yet in the Panthère they are not rival authorities. Venus is a complementary instructor who picks up the instruction of the disciple where the magister amoris leaves off:

Bien sai que as esté tardis

Et coars: or soles hardis

D'ore en avant et corageus,

Sans estre vilain n'outrageus.

(lines 1049–52)

I well know that you have been timid and cowardly. So be brave from now on and courageous without being a fool or outrageous.

Halfway through the narrative, the disciple's uncertainty continues to be represented through the sheer number of authorities he requires.

What is the effect of this masterful lecture, or in the Poire , of the mock disputation? Far from securing the disciple in his knowledge about women, they create further setbacks. The workout with the master sends the disciple into a tailspin—the very antithesis of masterly control. Both narrators seem as far from the exercise of their discipline as they did at the outset. We find here another zigzag in the pattern of the disciple's story. For each promising step the disciple takes toward practicing his knowledge about women there is another that turns him away from her. His progress is erratic, his attention divided. It is customary to explain this irregular pattern in terms of erotic desire. Its cycle is seen to generate obstacles that cause the man to lose track, thus intensifying his desire. Yet in the disciple's case, his zigzagging suggests the pattern of casting the woman herself as an obstacle. Insofar as the clerical world of mastery creates a

strong disjunction between the class of women and learning, one individual woman represents a perennial threat to that learning. She inspires misgivings about its command. Each time the aspiring disciple approaches his woman reader in order to test his learning, his confidence is necessarily undercut.

In the Poire , this loss of control is figured by the trope ravir . The disciple complains of being dispossessed progressively of his faculties:

Mes or les sant, car un essoine

si grant com de perde la vie

m'a del tot ma pense ravie.

—Ta pense?—Voire.—En quel maniere?

N'a tu ta penssee premiere

e ton savoir et ta vertu?

(lines 631–36)

But I feel them [the pains of love], for a worry as serious as the loss of life has seized my entire thought.—Your thought ?—Right.—In what way? Isn't your first thought with your knowledge and your power?

At stake are the very qualities that distinguish a rational man according to scholastic thought. Not only is the disciple distracted, but the defining traits of the master—his savoir and vertu —are severely compromised. He too suffers the predicament endured by Aristotle in the Lai : he is overwhelmed by a woman. His is a state of enthrallment. Let us not forget that this same term ravir evokes the ravishment or overwhelming of women. This is how Helen's abduction is described in the portraits of exemplary lovers at the beginning of the Poire (line 221). The echo is telling, for it reveals how the disciple's state is associated with women's conventional helplessness.[15] Granted, in the narrator's case the act of being carried off physically is transposed figuratively and refers to a loss of rational functions. Yet to link the two ravissements implicitly signals just how far the disciple is from the stance of intellectual mastery.

In the Panthère the disciple's vulnerability is underscored further. Whereas the Poire narrator's ravissement suggests an initial composure and expertise that is subsequently diminished, the Panthère narrator is already on the brink of collapse. Even the lecture on vernacular learning cannot steady him. In the face of actually addressing a woman, he is reduced to a subhuman state, emblematized in the following image:

Car paor lors site court seure

Et si t'atorne en petit d'eure

Que ne pues nis la bouche ouvrir

Por ta pensee descouvrir,

Si come .i. ymage entaillie,

Qui n'a vois, ne sens, ne oÿe.

(lines 1120–25)[16]

For fear has surely dogged you and turned you around in no time at all so that you can't even open your mouth to reveal your thought, just like a sculpted figure that has no voice, or sense, or hearing.

No Pygmalion, this Panthère disciple is, in fact, likened to his female creation—"a deaf and dumb image" as the Roman de la rose describes her (une ymage sourde et mue; line 20821). Instead of the artist who tries to create a woman, he is the created object—inert and struck dumb by his incapacities. This inanimate state represents the narrator's nadir point. And it is bound up tightly with the single instance of the woman's reported speech. Her voice rings condescendingly:

N'aiez en moi nule atendance,

Car sachiez que nule baance

N'ai d'amer, ne point de corage,

Si n'y avrez point d'avantage. . . .

De moi si tost s'esloigna donques,

Que respondre ne li poi onques.

(lines 1456–59, 1464–65)

"Don't have any hope in me. For you should know that I have no desire to love, nor indeed any will. Thus there is absolutely no gain for you." . . . She took her distance from me right away so that I could not respond to her in any way.

Such a curt rejection sends him to the lowest point yet, the dead center of the narrative.

If this state of paralysis poses questions as to the disciple's ultimate mastery, it also recalls the paradoxical strategy of taking a submissive stance toward another as a way of acquiring power. Like the middle-class lover in Andreas Capellanus's De amore , the disciple adopts a position of weakness before a magistra in order to gain the upper hand. Describing himself in extremis is meant to project her into the same place. Will she too be ravie ? This state of enthrallment thus bespeaks both the ambitions and the limits of that intellectual mastery sought by the disciple. It discloses ambitions because the figure of ravishment communicates subliminally his aim of taking charge of the woman reader. Faced with the prospect of losing control, the disciple attempts to convert that loss to his advantage by transferring it onto the woman. However, in light of his trials of uncertainty up to this point, there are few assurances that such a design can work. And here is where the limits of mastery are discernible. No matter how well tutored

the Poire and Panthère narrators are, their learning brings them no closer to exercising an intellectual authority over women. Working earnestly to command his woman reader, the disciple is never sure that he will succeed in doing so. The impetus to achieve mastery over the woman reader is broken by the suspicion that it is no sure thing.

Learning to Write

This uncertainty increases the pressure to practice the masterly craft of writing. As the Poire and the Panthère represent it, one chief way to regain the hope of intellectual mastery vis-à-vis women is to concentrate on perfecting textual skills. At the point of the disciples' greatest weakness, both texts begin to narrate the formation of a writer. The inference is that the exercise of composition could bring them some greater success than their other clerical training: writing may yet make them masters.

In the case of the Poire , once again, an acrostic reveals the real challenge of the disciple's writing. The disciple's loss of control is enunciated in the very place where the woman's name takes shape. With each letter of A.N.N.E.S., the disciple's "ravishment" is accentuated:

A. et se te vels vers lui deffendre,

il te vendra a force prendre.

(11. 864–65)

N. ge le vos di, bien vos gardez:

vos n'i avroiz ne pes ne trive,

ainz vos prendra a force vive.

(lines 993–95)

E. lors vint Amors qui me menace,

si ge ne me rent tot a lui.

(lines 1160–61)

A. And if you want to defend yourself against him [Love], he'll take you by force.

N. I'll tell you, be on your guard: You'll have neither rest nor respite, for he'll take you by great force.

E. So Love came who threatens me if I don't offer myself up completely to him.

Yet, by the same token, describing his own loss of control in the process of constructing a woman's name is a mode of self-discipline. Moreover, it is a

gesture of power, for it evokes the originary and divine act of creating a person by composing her name. It mimics Adam's naming of the animals that established his sovereignty. Here the Poire disciple's naming of A.N.N.E.S. is tantamount to an imperative. Not only does it bring her into being textually speaking, commanding her to be for the purposes of his text, it also uses her nominal being to communicate a single message: follow my example—offer yourself up. She exists insofar as she is meant to duplicate the disciple's own condition of "être pris à force vive." Because the woman is understood primarily as his textual creation, her being is inextricably caught up with the transferable message of ravishment.

That writing enables the disciple to reestablish a modicum of control is made even clearer by the woman's appearance. In contrast to the Rose and many other narratives with inscribed women readers, the Poire represents "A.N.N.E.S." entering into the discourse: she speaks. And this speaking entrance signals her ravishment. As soon as the woman promises herself to the disciple, he observes: "Love carried my lady away for me, and took her there where it pleased him." (Amors m'ot ma dame ravie et l'en mena la ou li plot; lines 2300–2301). The sheer repetition of the ravir trope over the course of her name culminates in the woman's seduction: she is represented "ravie" (line 2300).

The disciple's transfer of loss of control seems to work—so well, in fact, that the woman is also figured naming the disciple acrostically. T.I.B.A.U.T. marks the textual space where the woman articulates her desire for him. These letters, however, detail aspects of the disciple's position rather than her own. They relay further canonical advice about how to win the woman over: the importance of gifts, of dialogue, of taking swift action (lines 2466–78, 2537–61, 2623–28). Her naming of him is thus conjoined to his experience. Far from a sovereign act of nomination, it is a ventriloquistic stunt: she is calling to him through his writing. Let us not forget that when the disciple's acrostic has her saying "Friend, you will have sovereignty over me," we have another textual figure for the woman's yielding. (V os avroiz la seignorie amis, sur moi; lines 2568–69).

At this point we can see how crucial the letter games are for the disciple's potential mastery. The clerkly exercise in writing enables him to simulate control over his woman reader. In fact, the acrostic proves to be the site of the disciple's vicarious experience of mastering her.[17] There—in the most elementary, alphabetic way—he can spell out her reactions and legislate her desire. And this he does without ever representing an actual encounter or extended dialogue between them. Like so many "men of words," the disciple exploits the clerkly practices of writing as a way of figuring his control. Granted, this acrostic control is predicated on the idea of a fully literate woman reader. It presupposes a persona able to decipher the

most sophisticated textual forms. Her literacy is the foil necessary for the disciple to project a semblance of dominance. Yet within the terms of the ars dictaminis , it matters less whether the receiver of the disciple's letter conforms to his representations of her or not. What counts is the power the clerks' written medium affords him in creating the guise of his own mastery.

When we turn to the Panthère , this recourse to the powers of writing is no less in evidence. The key trope is that of oeuvrer :

. . . Tu te doutes

Por noient, gette jus les doutes;

Amans doit toujours esperer

Que son desir puist averer,

Encores n'en soit il pas dignes;

Car c'est de bien amer .i. signes.

Et s'ainsi estoit que tu fusses

Refusez, et bien le sceüsses,

Si ne t'en dois tu pas retraire

De bien dire ne de bien faire.

Oeuvre par sens, et si t'avise;

Car se tu selonc ma devise

Veus ouvrer, moult grans avantages

T'en vendra, et as amans sages

Par ce faire te comparras.

(lines 1502–16, emphasis mine)

You are a doubter for nothing, cast away your doubts. A lover should always hope that his desire will be realized, otherwise he would not be worthy of it. For this is one sign of loving well. And if indeed you were refused, and well you know it, you don't try to speak and act well. Act [oeuvre ] sensibly, that is what I advise you; for if you wish to work according to my precept, you will gain a great advantage, and in the doing you will be compared to wise lovers.

For the disciple to realize both his erotic and intellectual desire, Venus tells him, he must commit himself to hard labor: work is required. This trope should remind us first of the travails the disciple endured early on in the narrative. There he was represented struggling to no avail—completely overextended (lines 685–736). At the same time, Venus's work order suggests a type of productivity that goes beyond the hackneyed labor of love. In the allegorical terms of the disciple's training, it also involves a hermeneutical labor. The task is for him to decode the various allegorical signs, including that of the lady-panther. His industry should yield interpretations of the many significances of his world. What had

first seemed undecipherable—including the woman—becomes gradually comprehensible.

This hermeneutical dimension of the Panthère 's trope brings to the fore an important implication as far as the disciple's mastery is concerned. While he labors away, his love letter is materializing. In fact, the end result of his endeavors, his "ouvre" (line 1514) is his "salut," his "oevre" (lines 8, 2599).[18] The culmination of his personal travail is nothing less than his text. That the trope registers in this double way is made clear by the many scenes of composing in the second part of the narrative. The first sign of this creativity is the disciple singing himself. In the place of his various instructors, he speaks through the songs of Adam de la Halle. Admittedly, his composition works by way of a vox prius facta —an oft-quoted external voice of authority.[19] Yet as we have seen, such a mixed voice can demonstrate the disciple's capacity to incorporate the materials of vernacular learning. Adam de la Halle's authoritative voice is now assimilated, used as an integral part of the disciple's own writing project.

This emphasis on the disciple's textual work increases with the final recommendations of the God of Love:

Et quant un poi la pues veoir,

Si pren en ton cuer hardement,

Et li di tout apertement

Comment por li visa martire.

Après ce li porras escrire.

(lines 1733–37)

And when you can see her [the lady-panther] for a little while, then take her in your heart confidently, and tell her openly how you live a martyr's life for her. After that you will be able to write her.

The disciple looks more and more like Pygmalion—creative, confident, able to create a woman for himself out of nothing. The clerical practice of letter writing is no longer a tortuous ordeal for the disciple but has become his very livelihood. All the effort in textual study played out in the course of the dreams can be put to good use. In fact, the principal lesson from the dream experience—always work away loyally—is so fully assimilated that the disciple begins to compose his own oeuvre : the dream labor is transformed into his own "collected works"—the all-encompassing Dit de la panthère . The entire cycle of his insecurity and disastrous first approach to the woman is now recounted confidently in a textual sequence of his own making. And through that sequence his intellectual mastery is posited.

In this case, the disciple's increasingly masterful writing does not project a woman reader's response. Because he represents a far more insecure persona than his Poire confrere, the commitment to textual work is

all-absorbing. There is little space for figuring the woman; no simulated dialogue between them ensues. In contrast to the Poire , the Panthère foregrounds a failed encounter. Yet that very failure proves the mainspring of the disciple's creativity. Having hit bottom, he rises to the clerical task of writing as a way to secure the self. In other words, writing is pursued in order to turn the disciple into a master. We might even say that writing is pursued for its own sake. As it turns out, the God of Love's recommendation to direct his text toward the woman is rhetorical.

Intransitive Lessons

Does all this textual labor work? Does the disciple become the woman reader's master through writing? If we recall the clerical pedagogical model outlined in chapter 1, the cardinal factor is dialogue. It is the giveand-take, the heated exchanges between magister and disciple in a disputation, that prime the disciple for assuming authority. By expending his adversarial energy dialogically, the disciple accedes to the master's role. Both of these narratives rehearse these sorts of exchanges: the disciple shadowboxes with a masterly persona represented by disparate voices. Yet the crux lies in the problem of recasting that hypothetical dialogue to include the woman reader. Only then could the disciple be shown to exercise mastery fully.

In the Poire , the makings of such dialogue are visible. As we have seen, not only does the woman speak the disciple's name but the two are represented speaking to each other. The third and final acrostic is a duet with the disciple and woman taking turns composing the word A.M.O.R.S. Their voices are intertwined in the act of producing a text together.[20] Yet does this common text substantiate dialogue? To be sure, it caps a sequence of acrostics that serve to juxtapose the disciple's and the woman's words. What was first a matter of literal juxtaposition develops into a type of interaction. The Poire climaxes with an exchange—disciple to woman and vice versa. But if we consider this represented exchange in terms of the disciple's letter writing, it is by no means clear whether it is transferable to the woman reader. The ideal scenario of their union is certainly intended to convince her to respond favorably to the letter. However in the end, the narrative cannot establish that. Whereas it posits an obvious synchrony between A.N.N.E.S. and the inscribed woman reader, one meant to determine an identical positive reaction to the disciple, that reader's interest in dialogue cannot in the end be represented. It remains the moot point in the narrative.

In this sense the disciple's prospects for gaining authority over women

through dialogue are deeply ambiguous. Because the woman reader is never depicted responding one way or the other, his authority is never validated. It is as if the dialogue he has projected remains intransitive.[21] Given the woman reader's silence, the disciple is in a hiatus. All his training and textual exertions have brought him to this: a position where his hopes for intellectual mastery of women are held in abeyance. The privilege of acquiring the master's doctrine about them does not translate automatically into practice.

This pattern of intransitivity is even more pronounced in the Panthère . As we have seen, the shock value of a woman is so enormous for this disciple that most of his energy is expended on gaining control of the self through writing. The disciple's work is complete when it describes his subjective condition (de tout mon estat descrire; line 2629), and not his understanding of women. Exchange with the woman reader thus looks hypothetical at best. "Were you willing to say this rondel. . . . If I would hear this from you": the Panthère represents the one scrap of dialogue conditionally (Que vous veilliez cest rondel dire. . . . Et se de vous oÿ l'avoie; lines 2512, 2527). The disciple imagines what it would be like were the woman to sing a rondeau in answer to his. Unlike the Poire , which goes so far as to project a woman's response, this narrative casts it as an as yet to be realized speech act. The woman's direct discourse is manifestly beyond the disciple's limits. Even within the freer dream space of the text, he cannot entertain interaction with the woman. In the Panthère , an intransitive relation exists with the allegorical lady-panther as well.

Such intransitivity provides a key to discipleship as it is represented by allegorical narrative. It extends far beyond the syntactical issue of dialogue and epitomizes the narrator's dilemma over failing to realize the master's lessons regarding women. This dilemma is anticipated from the beginning of the disciple's initiation. He undergoes increasing trials in order to prove his intellectual credentials. The process is protracted, pushed beyond the extreme model of the Rose . Yet with this extended initiation comes no greater certainty that he can apply his learning on specific women. The disciple's authority does not carry beyond his own solipsistic writing. While he enjoys avidly at second hand the representation of the woman's acquiescence, the clerical practicum of letter writing insures no follow-through.

In this gap between the master's doctrine of women and the disciple's discipline we can detect what Bourdieu calls the double-edged privilege of domination.[22] In both these narratives, the disciple is motivated by the desire to prove his mastery through his letter. Yet insofar as that writing can never guarantee domination of the one persona that eludes him—his woman reader—he as much as she risks being dominated. The paradox

lies in the disciple's stubborn determination to prevail. By trying over and over again to put the master's lessons about women into textual use, the disciple becomes spellbound, caught in the grip of a desire that is never fully satisfied. As a consequence, he too is subject to the immense pressure of a discursive system that can turn intellectual authority into a form of domination. He too can be imposed upon.

In recognizing this paradoxical position of discipleship, we should not discount the fact that the disciple remains a prominent and respected figure in French medieval narrative. The story of his trials contributes indispensably to the notion that women can be known and that some disciples can indeed graduate to the station of magister . But to the degree that the disciple is represented as so overwrought, his writing bears the signs of mastery's limits. To the degree that his authority over women is never confirmed, the symbolic dominance that his writing should put into place is, in the end, a doubtful affair.