19—

Modern Prince and Feudal Lord

Economies like cutting pensions and reducing Court expenditure, extravagance like the making of Richmond Park, create enemies, but on the whole the raising of money makes more. Weston was more aware of the difficulties than Charles himself. He was already stepping up the receipts from the customs houses in what was likely to be the biggest contribution to the King's finances, but his natural caution enabled him to foresee danger in some of the other money-making devices that Charles was contemplating. A Treasurer whose influence was on the side of caution was bound to have some effect upon the King, yet Charles was never deflected from any purpose he had in mind: he simply used other instruments if one failed him. The influence of Laud was less direct. His natural austerity acted as a break upon expenditure, his urge to improve the King's finances caused him to press economy and pursue money-raising devices with a ruthless integrity. Unlike Weston, he seemed utterly impervious to the dangers of arousing vested interests.

In the raising of money by the sale of monopoly rights in various forms Weston was particularly cautious, while Charles was at his most expansive, carrying his Council with him into an amazing series of projects. The granting of monopoly rights of production, sale, or management in return for a fee or rent had become a scandal even in Elizabeth's time and James had agreed to the abolition of the practice. The Monopolies Act of 1624, however, allowed two exceptions which were in accord with public sentiment. The first was in respect of new inventions or infant industries where it was considered reasonable to allow a period of monopoly protection. The second was in respect of corporations. Seventeenth-century opinion was still widely influenced by the medieval concept of the corporate society in which trades and trading bodies, towns, religious organizations and

fraternities were organized on a corporate basis and acted as monopoly bodies. To have pronounced these illegal would have been to remove the underpin from society itself. So, in spite of abuses, corporations remained, with new inventions, outside the scope of the Monopolies Act. That Act, however, had not intended, and could not have envisaged, the mushroom growth of patents and monopolies which came into being under cover of these exceptions.

A Crown monopoly of playing cards and dice gave the King a fifty per cent profit on sales. Monopoly rights to individuals included the transport of lamperns, the making of spectacles, combs, hatbands, tobacco-pipes, bricks; there were monopolies for the gathering of rags, for sealing linen cloth and bone lace, for gauging butter casks, for transporting sheepskins and lambskins. Sir William Alexander was given a patent for printing the Psalms of King David translated into English metre by King James. The rights were all paid for in one way or another. John Pearson and Benjamin Monger of London 'set forth the inconveniences and mischiefs which arise from dishonest servants, and the impositions practised by charewomen and dry nurses'. They proposed a Register of Masters and Servants, the fee being 2d from the master and 1d from the servant, and they offered the King a payment of £10 a year for the privilege of the sole running of the registry.[1] Charles liked the idea and the project was approved. Somewhat different was a scheme proposed by Sir John Coke, which never saw the light of day, for the formation of a Loyal Association, whose members, besides paying an entrance fee, would pledge themselves to serve the King in person, goods, and might. They would be distinguished by a badge or ribbon in the King's colour and would be entitled to precedence at public gatherings.[2]

Frivolous or lightweight as most of these projects appeared, others were in line with an economic self-sufficiency that for hundreds of years had been the goal of the King's ancestors. Elizabethan statesmen, as well as his father, had pursued this end and many of his own most influential subjects were urging its necessity. Mansell's glass patent, which Charles renewed, might be considered in this category; the alum works whose monopoly Charles continued, certainly could be; when Sir Thomas Russell was licensed to use a process of his own invention in the production of saltpetre, Charles was following the lead of Elizabeth and of James; a crown monopoly of the sale of gunpowder followed naturally and, besides being profitable, could be justified on grounds of national security. The saltpetre monopoly ran quickly

into difficulties when the Admiralty learned that some saltpetre men were being over-zealous, abusing their rights of search for the raw material by digging in barns and churches, houses and sick-rooms regardless of the old, the sick, and women in childbed, undermining walls and making great holes which they failed to fill up. But the Government needed saltpetre and Charles caused a Proclamation to be made in 1634 empowering any three or more JPs to 'enter, break open, and work for it in the lands and possessions' of himself or of any of his subjects in England and Wales.

In incorporating William Shipman and others as the Society of Planters of Madder of the City of Westminster, he was again following the lead of his father, who had already attempted to restrict the import of this important dye in order to render the cloth industry more self-sufficient. In turning his attention to salt, seeking to substitute a native product for the imported article, Charles was pursuing the same well-trodden path towards self-sufficiency. In 1636 he prohibited the import of salt from Biscay and issued licenses for its manufacture and sale in England, hoping to receive ten shillings a wey for his support and protection. Unfortunately the contradictions inherent in the policy of self-sufficiency were glaringly obvious in this case: the price of salt rose and affected the fishing industry, particularly the important herring fishery, which depended upon salting its catches; Trinity House complained that ships which had formerly brought back salt from Biscay now returned unladen from the south of France and might be compelled to abandon their voyages altogether; while the benefit Charles received from the granting of licenses was partly offset by his loss of duty on the imported product.

The patent for soap demonstrated the same mixture of motives as well as providing one of the most colourful episodes of the time. Again the project had been aired in James's reign and was an attempt to raise Crown revenue while promoting self-sufficiency. Foreign soap was excluded and the home-produced article was to contain nothing but native materials. To this end a group of soapboilers was incorporated in 1631 as the Society of Soapmakers of Westminster, and was instructed to use vegetable oil in place of imported whale oil. This obligation extended to all soapboilers and its enforcement was put in the hands of the new company. To make control easier the production of soap was confined to London, Westminster, and Bristol. The new Society thus held a virtual monopoly of soap manufacture, and in order to protect the consumer the price was fixed. The King was to

receive a payment first of £4, later of £6 a ton of soap marketed. But the public did not like the new soap, and the old was soon selling at higher prices as independent soap boilers continued to produce clandestinely. They were called before the Star Chamber but neither their punishment nor testimony from selected witnesses, including the Queen's laundress, could convince consumers that the new product was as good as the old; rumour, indeed, had it that the Queen's laundress continued to use Castille soap. Public laundry trials organized in the City of London gave conflicting views on the efficiency and 'sweetness' of the new soap; as a final throw the independent soap-makers offered the King an annual payment of more than the new society was paying and the monopoly was bought out. But these operations enhanced the price of the product and, although Charles continued to reap as much as £18,000 in 1636, the best year, his subjects were the losers.[3]

Charles made no attempt to control any basic industry. A government monopoly of coal was considered but the Committee for Trade advised against this on the grounds that it would raise the price and arouse the 'clamour of the people'. It would also have meant confronting the powerful monopolists who already controlled the industry and who doubtless had influenced the verdict of the Committee. If it could have been managed, control of a basic industry would not only have been financially advantageous to Charles but would also have bolstered the aim of economic self-sufficiency which, as it was, appeared to be pursued in somewhat piecemeal and haphazard fashion.

Trading monopolies had, on the whole, even less to say for them. The Company of Vintners, for example, paid to the King a duty of 40/- a tun of wine sold in return for monopoly rights of sale and an increase in price of one penny a quart on French wines and twopence a quart on Spanish wines. Charles farmed the tax to a group of vintners for £30,000 a year, but it is doubtful whether he ever received as much as this.

The group of projects which covered inventions was mixed. In agriculture there were many schemes for drainage, several inventions for mechanical sowing and for improved ploughs. A patent for the much-needed cleansing of the Thames did more harm than good in scooping up gravel from the river bed 'and making great holes'. In view of the feared shortage of timber it was, however, timely to give a fourteen-year patent to Dud Dudley and his partners for smelting iron

with coal, or with peat or turf, in return for an annual rent; it was reasonable to license Edward Ball to prepare peat by reducing it to a coal that would 'serve for melting iron, boiling salt, and burning brick'. The many new patents for the drainage of mines, like that granted to Daniel Ramsay and his associates 'for raising water out of pits by fire' showed, possibly, a too-credulous belief in experiment. Sir Henry Clare, searching for the philosopher's stone, strained that credulity too far and Charles turned down his request for financial aid. There was, however, a lively interest in hidden treasure. In April 1630 Francis Tucker and his associates were given licence to conduct such a search on the understanding that Charles received one-quarter of anything they found. Two years later Charles listened to Richard Norwood who had 'found out a special means to dive into the sea or other deep Water, there to discover, and thence by an Engine to raise or bring up such Goods as are lost or cast away by Shipwracke or otherwise' and he licensed search in the water as on the land.[4]

Charles was present to hear the case made by Thomas Russell for the use of human urine in the manufacture of saltpetre. Russell estimated that if 10,000 villages, each with forty houses occupied by four persons who all cast their urine upon a load of earth for three months, and then let it rest for three months longer, ripe saltpetre would result. Feeling, perhaps, that this was a viable alternative to the ravages of the saltpetre men, Charles ordered all cities, towns, villages and other habitations to use their urine in this way, guaranteeing that the earth would be taken from them without trouble or charge,[5]

Charles and his Council were certainly attracted by anything out of the ordinary, and the exuberance and inventiveness of the time was encouraged by their support. Charles himself was genuinely interested in projects, and his eclectic mind enjoyed ranging over the schemes brought before him. He was eager, assiduous, hardworking, even if, together with his Council, a trifle over-sanguine and too ready to attempt to fill the royal purse at the expense of credulity. An Order in Council later lamented the various licenses which had been procured 'upon untrue suggestions' or which in execution had been found to be 'far from those grounds and reasons wherefore they were founded' and which proved 'very burdensome and grievous to the King's subjects'. Using the expression that James had used when things went wrong, they complained that they had been 'notoriously abused'.

Charles received a valuable income from his monopolies and patents: though less than £30,000 from wine rather more from the soap

monopoly: a useful £13,000 or so annually from tobacco licenses: a small but helpful £750 annually from his monopoly of playing cards and dice: rents from the alum and glass works: small sums from the various patents he sanctioned.[6] Several contemporaries asserted that he was being defrauded and received but a fraction of what was intended. More serious was the criticism that since there was nothing to prevent the fees which were paid to the King from being passed on, it was the consumer who paid the King's commission in the form of higher prices. A discriminatory excise on luxury goods could have brought in as much and caused less hardship to the poor though possibly more protest from the rich. Charles excused himself by remembering that England was still the least taxed country in Europe, with no official excise and no regular direct taxation. Certainly projects and monopolies were not the most efficient nor the most equitable way of raising money, but in the absence of any other form of taxation it was possibly more appropriate to criticise the nature of the project itself than the fact that it imposed a tax upon the community. A tax arising from the monopoly of an essential article like glass or soap was different from a tax imposed in order to foster a new technique in industry or agriculture. Taxes on playing cards and dice were annoying rather than burdensome to the public. The real abuses were taxes that affected industry and reacted on workers as well as their employers, the monopolies that rebounded against themselves by causing shortages and dislocation elsewhere. On the credit side were benefits like the infusions of capital which followed the new leases issued to the Mines Royal and the Mineral and Battery Works, the encouragement of the home production of the important wool cards by a prohibition of import; and there were other grants, restrictions, and prohibitions whose value depended upon the point of view, such as the prohibition of the use of brass buckles as being not so serviceable as iron. Obviously, in considering methods of raising money a line had to be drawn somewhere. Charles drew it by not debasing the coinage, by not taxing food, and, while allowing the price of wine to be enhanced, by not taxing the people's beer.

In a somewhat different category were schemes bequeathed to Charles by his father which concerned water supply and land drainage, both matters of concern to a growing population which required both water and food, and both possible means of channelling money into the Exchequer.

Sir Hugh Myddelton, a Welshman with a lively interest in affairs and with financial and other connections in the City where he practised his craft as jeweller, goldsmith, banker and clothier, was among those who had been considering the idea of a continuous supply of sweet water to London. He was a great friend of Sir Walter Raleigh with whom he would sit outside his goldsmith's shop, smoking tobacco and talking endlessly of projects and exploration while the London populace looked on. It was possibly then that the idea was born of channelling springs of fresh water from Chadwell and Amswell, near Ware in Hertfordshire, by means of an artificial waterway or New River to Islington on the outskirts of London, where it would flow into a reservoir to be called the New River Head. James already had dealings with Myddelton as a jeweller, and his curious mind was attracted when he saw engineers making investigations near Theobalds on Myddelton's behalf. In 1612 James agreed to pay half the cost of the works, past and future, in return for half the profit. The first stretch of New River was completed by 1617 when it was opened with considerable festivity and enthusiasm. James had by that time contributed over £9000 to the enterprise but profits were not high and in 1631 Charles commuted his inherited half-share to £500 a year.

But there were still many families in and near London without sweet and wholesome water or, indeed, without access to water for cleansing or for fire-fighting, and when in 1631 projectors claimed to have discovered new springs, hitherto unused, that could be channelled to London and Westminster along a stone or brick aqueduct there seemed no reason not to licence the undertaking. That Charles did so with care was an answer to those critics who blamed him for sanctioning 'rival' projects. The scheme commissioned in 1631 was supplementary to Myddelton's and its provisions were carefully laid down. In spite of Sir Hugh Myddelton's work, ran the caption to the grant, 'Wee are credibly informed that there are very many families, both within the Citty of London, and the suburbs thereof and Streets adjoining in the County of Middlesex, which want sweet and wholesome water to Bake and Brew, Dress their Meat and for other necessary uses, and cannot fitly be served or supplied with any the Water works which are now in use.' The licence was to bring water to London by an aqueduct of brick or stone from any spring or springs, pool or pools, current or currents, place or places within one-and-a-half miles of Hoddesden and to disperse it through several pipes, provided that hitherto untapped sources only were employed and that

their use did not 'diminish any of the Springs, or take away any of the Water' already brought to London or Westminster by Sir Hugh Myddelton. Charles's share of the profit was to be £4000 a year and he authorized the holding of a lottery or lotteries in any town or city of England to help raise money for the project. Lotteries were popular among his subjects — the more so since none had been organized for some time — and the tickets were soon taken up.[7]

Under the influence of the Dutch the reclamation of swamp and fenland by drainage had also been considered. Henry VIII had drained marshland at Wapping, Plumstead and Greenwich and there had been similar small-scale enterprises for an immediate purpose. But little as yet had been done to reclaim large areas of land where long-term planning and a great deal of capital would be required. An obvious target was the Great Level of the Fens which stretched inland from the Wash to cover an area of nearly 700,000 acres. It was watered by six rivers which overflowed their banks constantly in winter and frequently in summer so that throughout the year the area was a flat, watery plain where the inhabitants walked on stilts or travelled by boat. Fishing and fowling dominated their lives, yet when the waters retreated the soft earth was covered with lush grass for cattle and sheep, and there was always turf and sedge in abundance for firing, reed and alder for thatching and furniture-making.

The fiercely independent people who lived there were content with the life they knew and, with fish and fowl in abundance as well as cattle and sheep, a modicum of crops and the normal fare of the farmyard, they were probably better-off than many small farmers living more conventional lives. Even the less well-off among them were better placed than they would have been in a more organized society where they would be classed as sturdy beggars under the Poor Law. The basic wealth of the area was shown, indeed, by the churches, cathedrals and monasteries which had been raised over the centuries in stone brought from outside the fenland by barge down the many rivers. Naturally enough the possibility of drainage had been considered. But although the area was potentially rich and the prospects of profit were high, drainage was expensive, most of the inhabitants were content as they were and, apart from the bigger landowners, there was little interest in land reclamation. Particularly bad periods of flooding were dealt with by ad hoc Commissions of Sewers until the area reverted to its old life.

A growing population made the prospect of a larger farming area

more attractive, and James, dramatizing the situation after his own fashion, had announced that 'for the honour of his kingdom' he 'would not longer suffer these countries to be abandoned to the will of the waters'. Accordingly, he engaged the Dutch engineer, Cornelius Vermuyden, and sponsored the work of reclamation in return for 120,000 acres of the reclaimed land. James died before the work was begun but Charles carried on, at first content for local landowners to act as undertakers, putting up the money, shouldering the risk, and claiming their proportion of reclaimed land. But nothing came of this and in a welter of conflicting opinion, which included opposition to drainage itself and opposition to Vermuyden as contractor, the rivers got completely out of hand and several smaller owners of permanently flooded land approached Francis, fourth Earl of Bedford, who owned 20,000 acres near Thorney and Whittlesay, to help. In 1630 the Earl contracted to improve all the southern Fenland within six years so that it would be free of summer flooding. Thirteen others joined him in putting up the capital, Vermuyden was put under contract, and in 1634 Charles granted a charter of incorporation for the drainage of the Great Fen. Charles's fee for the charter was to be 12,000 acres of the drained land out of the 95,000 which would fall to Bedford.

By the autumn of 1637 the undertaking appeared to have succeeded and Charles received his 12,000 acres of land. But the work had been done against a background of opposition and rioting by the local population, not only because they feared to change their ways, not only because, in the reapportionment of land, many commoners lost their rights of pasturage and of fishing, but, more fundamentally, because the Great Level was an area which could not be stereotyped or subjected to any basic rule of thumb. Levels of flooding were different; some flooding was gainful; the prevention of flooding in some places merely inundated others which had previously been dry.[8] Charles saw nothing of this and he was obviously not familiar with the detailed geography of the Fens. Even Vermuyden, who planned and carried out the bulk of the work, lacked adequate topographical knowledge: both men could have relied more heavily upon local advice. Even so, Charles and his Council acquired a considerable understanding of the problems involved. Charles, for example, instructed the Commissioners of Sewers on the north-east side of the river Witham that, although their lands had been drained, it was necessary, in order to keep them dry, to maintain the river banks in repair between specified points. He showed care for the poor in instructing the Commissioners

in charge of apportioning land after drainage to convoy 2000 acres to the use of poor cottagers and others, and he was sufficiently astute to order a proportion of reclaimed land to be tied to the perpetual maintenance of the work.[9]

But when a way of life is disturbed, when outsiders make foolish mistakes, such concessions are unimpressive. All over the Fenland men and women came out with pitchforks and scythes to fend off the innovators. Sometimes a landowner of greater sophistication would offer a more durable form of defence as in 1637 when Mr Oliver Cromwell of Ely, in return for a groat for every cow upon the common, offered to hold the drainage commissioners of Ely Fen in suit of law for five years. But Charles himself intervened shortly afterwards. He was not satisfied with the way the drainage had been carried out for, although the Fens were now free of flooding in summer, they were still subject to winter flooding. After many complaints had been received by the Privy Council he stepped in personally, declared himself 'undertaker' and promised to make the Fens 'winter as well as summer lands'. Meantime he gave the inhabitants full rights over their lands and commons until the work was completed and the final apportionments made. Before that was accomplished both he and Mr Oliver Cromwell had been swept along by events even more important than the drainage of the Great Fen; when they came face to face it was upon other issues.[10]

Charles liked to see himself as an 'advanced' monarch, patronizing inventors and giving scope to innovation and improvement. But he was also aware of his position as feudal overlord and was as willing to raise money from the one role as from the other.

Already in 1626 he had appointed a Commission to consider means of augmenting his revenue and reducing his charges. Among the matters under review were his forests and chases and now, with the help of Weston, Charles considered them anew. These large, dispersed areas were not necessarily wooded but were technically land reserved for royal hunting. Their native inhabitants were few and largely itinerant with a way of life that was simple and not necessarily meagre. Though they were subject to forest law instead of common law, which entailed severe penalties for interference with the forest or its wild life, royal connivance had left them for the most part in peace to a life freer and more fruitful than that of many peasants elsewhere. The royal forests contained also a few settlers whose existence was

connived at. Even enthusiastic huntsmen like James had not used all forest land for hunting, and as forest laws had fallen into disuse many peasants had, in fact, used the forest amenities as they would those of ordinary woodland or waste and had even brought some of the forest area under cultivation. Forest verges, in particular, had frequently come under the plough. In this way the extent of forest land had been reduced and dwellings, in some cases entire villages, had grown up within the bounds of what were technically 'forests'. Here and there richer men, some already big landlords, were deliberately farming large stretches.

The suggestion now was that royal forests should be restored to their ancient boundaries and that transgressors should be fined for encroachment or for infringing forest law within that enlarged area. In this way practices that had come to be considered normal would be penalized, whole villages — there were seventeen of them in the Forest of Dean alone — would be subject to penalty for breaking forest law, and even those who farmed the verges would be fined. Though much of this would be small-scale penalization, and not intended to be carried out, the amount of discontent which the very idea would generate was bound to be considerable. It was, however, the big encroaching landlords who were the real target.

The ancient office of Justice in Eyre, which administered forest law, was revived for the purpose and in 1630 the Earl of Holland was appointed Chief Justice with the assistance of Lord Keeper Finch, the Speaker who had been held in the chair in Charles's last Parliament. Neither man was popular. It fell to Finch in the Forest of Dean, where Holland took up his Justice Seat in July 1634, to make the important pronouncement as to what were legally considered the ancient bounds of the forests and to what extent, consequently, infringement had occurred: the King's claim was to the boundaries as enacted by Edward I before subsequent amendment and he was, therefore, laying claim to the maximum area of forest land, despite the changes of three centuries.

As expected, the fines imposed upon forest dwellers or little nibblers were small or were allowed to lapse, and the main penalties were reserved for the big and wealthy landowners. In Dean, where the Lord Treasurer himself was implicated, one of the largest fines, of £35,000, fell upon Gibbons, his agent, who was commonly thought to be the scapegoat. Sir Basil Brooke and his partner, who were said to have used trees set aside for the navy for their iron works in the Forest, were

fined £98,000 jointly, which two years later was commuted to £12,000. Enormous fines in the New Forest, in Rockingham and other forests were similarly reduced but in all brought about £37,000 into Charles's Exchequer between 1636 and 1640. Frustration, indignity, and a sense of injustice festered. It might have been legally defensible to reassert a boundary three hundred years old, it might have been equitable that untaxed landlords should make some contribution to the royal Exchequer in respect of lands and profits which they had acquired by no right but custom. But to impose a fine which was so large that it was certain to generate the maximum resentment and then to remit or substantially reduce it, was a policy of ill-advised, deliberate confrontation to no purpose. Not that this always happened. There were cases when the project worked more smoothly and Charles was paid all, or nearly all, he expected.[11]

Besides dealing with the ancient bounds of his forests and chases Charles had asked the Commission of 1626 to recommend how he could restore parts of them to a 'profitable cultivation'. In carrying out their recommendations he ran into agrarian troubles already rampant in three of his Western forests — Gillingham in Dorset, Braydon in Wiltshire, and the Forest of Dean in Gloucestershire.

In Gillingham lands had been granted to Sir James Fullerton and George Kirk, two of Charles's Scottish friends and Gentlemen of his Bedchamber. They were given licence to depark and proceeded to enclose and farm. But the forest dwellers, on the grounds that their ancient rights of common were being violated, pulled down the fences as fast as they went up. Messengers from the Privy Council were whipped and their orders burnt while soldiers in the neighbourhood rescued the few rioters who had been apprehended. In November 1638 the High Sheriff of Dorset brought in more troops but found 'a great and well armed number' of rioters holding their position under the slogan 'here we were born and here we stay'. Some eighty of them were fined by the Star Chamber, but a couple of years later the struggle was still continuing under a leader styled 'the Colonel'.

In the Forest of Braydon Charles was more closely concerned, for here he was attempting to enclose and farm himself. Commissioners whom he sent down to smooth the way were told that enclosure would spell the 'utter undoinge' of many thousands of poor people by depriving them of rights of common and other perquisites. Fences were no sooner up than they were torn down. The local people were very much at one, even the larger landlords sharing the claim to what

were looked upon as customary rights. Privy Council messengers were beaten up and were powerless to stem the destruction of fences and ditches or to silence the 'jeering and unbecoming speeches of the rioters'. Only by means of informers were some of the leaders apprehended. But Charles had no taste for this kind of struggle, and he granted large areas of the Forest of Braydon to freeholders and other tenants, while continuing merely a modicum of farming himself.[12]

The Forest of Dean presented an even more complicated picture, for here was a way of life that for three hundred years had suffered no external interference. The forest proper was in poor condition through lack of care, indiscriminate felling and failure to replace; in rough forest clearings, which often stretched for miles, small-scale agriculture and common land were interspersed with coal and iron-mining, with charcoal burning, with tanning and other small enterprises that depended upon bark or other forest products. Monarchs had long since abandoned the Dean as a hunting ground and its inhabitants responded to little law but their own. If Charles were to farm or to use the timber resources of the Forest systematically he would be stirring up dozens of vested interests. Under a leader called Captain Skimmington the inhabitants of Dean made it clear that they would tolerate no interference. They were in touch with the protesters in Gillingham and Braydon and, again, Charles was not prepared to force an issue. He got even less from his attempts to farm his forest lands than he did out of his forest fines.

More rewarding were the Crown lands proper. Sir Julius Caesar had judged them 'the surest and best livelihood of the Crown', in spite of the heavy sales of Elizabeth and of James which had much reduced their annual value, from around £111,000 in 1608 to less than £84,000 in 1619. Although he himself had been compelled to part with Crown lands to settle some of his debts, Charles succeeded, by careful management, in reversing the trend. Entry fines on new leases were raised; rents were increased, though they were still mostly lower than elsewhere; in cases where entry fines were fixed the tenants were sometimes persuaded to buy their freeholds at from twenty to fifty years purchase. His woods and coppices were surveyed, the timber trees numbered and valued and, where appropriate, were sold; new plantings were made and, where possible, enclosure protected the young growth. Charles noted the consumption of wood by iron works, and to reform 'the great waste of timber' appointed a Surveyor of Iron Works to exact fees in proportion to timber consumption. Judges of

Assize were instructed to implement existing laws governing the preservation of forests. But the Crown lands were scattered, frequently uneconomic in themselves, their administration was too often weak, costly and venal. Although Charles did succeed in raising his income from them, his careful work brought in not more than £10,000 a year from woodlands and £80,000 from the rest. A compact area of land, such as Salisbury's Great Contract had envisaged, would have served him better.

As a further result of the Report of the Commission on the raising of Money, John Borough, Keeper of the Records in the Tower of London, was instructed in January 1628 to search through his documents for precedents relating to another issue. His findings resulted in the appointment of a commission two years later 'to compound with persons who, being possessed of £40 per annum in lands or rents, had not taken upon them the order of knighthood'. And so knighthood fines came into being. It had been customary for every person of a certain standing to come forward at a king's coronation to receive the honour of knighthood but, as feudalism decayed, so had this practice, and for over a hundred years it had been in abeyance. Charles now declared that he would revive the practice and fine those who had not been knighted. The actual fine, assessed by local officials in accordance with a man's ability to pay, generally amounted to a sum between £10 and £100 and on average to about £17 ot £18 a person. Between 1630 and 1635 the 'business of no-knights' brought Charles about £180,000 in knighthood fines. There was little opposition, the levy was accepted as reasonable, and the individual sums were not large.

Forest fines and distraint of knighhood both arose from Charles's position as feudal overlord. A third form of revenue deriving from the same source was the most anachronistic of all. The rights of wardship depended upon the fact that many landowners still held their land, theoretically, on feudal tenure from the King by Knight service, and that he could exercise the feudal right of taking charge of their heirs who succeeded while under age. The Crown could administer the lands of these minors, supervise their upbringing and education and plan their marriages, through the Court of Wards. Idiots and lunatics of any age who inherited such lands came within the scope of the court; the re-marriage of widows who had been wards of court remained its concern. Though wardship originally comprised an element of protection to the minor, by the seventeenth century the Court of Wards had become a court of profit so brazen that wardships were

6

James I by an unknown artist, probably

shortly after his accession to the English throne.

7

Queen Anne, by William Larkin, 1612. The

Queen is in mourning still after the death of Henry.

8

Charles's sister, Elizabeth, as he knew her, from a

miniature painted about 1610 by Isaac Oliver.

9

Charles, as painted by Daniel Mytens, after

his return from Spain, probably in 1623. There

is diffidence still in his stance though his legs

are undoubtedly straight and do not look

noticeably short.

10

The Duke of Buckingham, also painted

by Mytens at about the same time. In

contrast to Charles his whole bearing

portrays confidence and command.

11

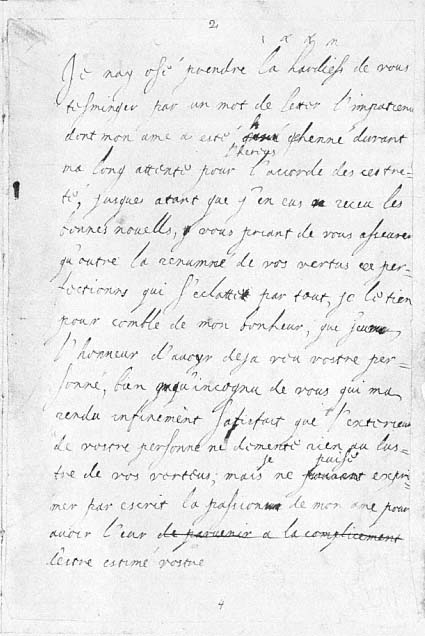

A page from a draft of Charles's earliest love letter to Henrietta-Maria, whom he

has not yet seen. His indecision and diffidence is still apparent in the many erasions

and, indeed, in the fact that he made a draft at all.

12

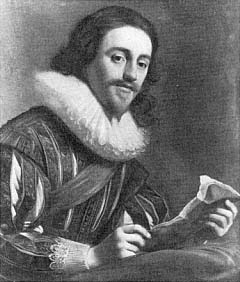

At the end of the 1620s, Charles passed into

the happiest period of his life. This portrait by

Gerrit van Honthorst, painted informally from life

towards the end of 1628 as a study for the great

canvas of Apollo and Diana , shows Charles as

a relaxed and happy man.

13

This unusual and informal representation of Charles at cards, at about the

same time, by an unknown artist of the studio of Rubens, is undoubtedly

based on descriptions by the master of the life he experienced at the English

Court. Charles's enthusiasm for card games is well attested.

openly sold, leases of wards' properties put up to the highest bidder, wards' marriages not only arranged but bargained for. Charles used his opportunities to the full. Whereas between 1617 and 1622 the net revenue from wardship had been just under £30,000 a year, between 1638 and 1641 it averaged close on £69,000 annually. As with other sources of revenue the mastership of the Court of Wards was not normally in royal hands but was leased for a fee: Salisbury had done very well as Master, Cranfield had held the post, Sir Robert Naunton held it from 1623 to 1635 when he was succeeded by Cottington.

Allied with wardship was livery, which derived from the King's feudal right to approve the succession of those who held lands direct from him and was now exercised in the form of a tax or fine of succession. Altogether sufficient vestigial feudal practices survived to make an appreciable contribution to the King's income. The reverse of the coin was that they also operated as a tax upon the King's landed subjects. Forest fines and Knighthood fees were once-for-all payments. Wardship and livery were the more pernicious in being continuous. Whatever Charles gained from any of them, it was not difficult to surmise that he would have to pay the price in some form of concerted opposition to his policy.