San Antonio and Phoenix:

Existing Elements Are Enhanced or Transformed in Positive Ways

The Grand Avenue enhanced retailing and employment opportunities in downtown Milwaukee and provided a new architectural setting for the Plankinton Arcade, the Woolworth Building, and several other existing structures. The Kalamazoo pedestrian retail district is reinforced by new developments and renovations nearby. By contrast, numerous shopping mall streets in other cities seem to have speeded up the decline of retail businesses and of employment. Clearly, effective reclamation of existing structures and uses needs strategic, subtle, and well-orchestrated intervention. In a case like Milwaukee's Grand Avenue, where a focus for pedestrian activity was removed from the street, there was a danger that the traditional sense of the existing Main Street along Wisconsin Avenue might be lost, that former fronts of stores might become "backs," that the inward-looking character of shopping centers might turn downtown streets into mere traffic arteries. Although routine development can have such unwanted side effects, thoughtfully conceived catalytic action does not.

The key to saving the pedestrian character of Wisconsin Avenue while introducing an internal pedestrian precinct at midblock was to provide retail space that fronts both on the mall and on the street. This was the pattern in the existing Plankinton Arcade; it was retained and employed elsewhere in the project as well. The existing department stores already

stretched through the block; adding midblock circulation increased access. Admittedly, had the census of pedestrians remained constant, the new internal circulation would have reduced pedestrian traffic on city streets. In actuality, the Grand Avenue attracts more people to it, thereby justifying the addition of new pedestrian precincts.

A mixed-use project proposed for downtown Indianapolis similarly demonstrates how a catalyst can enhance existing elements of an area. The program was for retail, office, and hotel uses interwoven with two blocks of existing buildings. Like the Grand Avenue in Milwaukee, the development would be barely noticed from city streets. Circulation and accompanying new construction would occur through the interiors of blocks.

Where new facades are needed, they would be designed in sympathy with existing ones. Although new elements, like a pedestrian bridge and two office towers, are introduced, the overall effect is one of carefully controlled design to protect and strengthen the character of existing buildings.

The case for preserving and recycling existing elements of the urban scene is well established. Ghirardelli Square in San Francisco (1962) provided proof on both aesthetic and economic grounds. Adaptive use is in fact so well established that it is difficult to find a city in which a warehouse or factory has not been reclaimed for another use. Thus it is the

55.

Indianapolis: the urban context.

56.

Proposed development to be fitted into the Indianapolis context, ELS / Elbasani and Logan, architects.

catalytic role of adaptations, not adaptive reuse itself, that must be argued, for rehabilitation alone does not ensure new and continuing vitality.

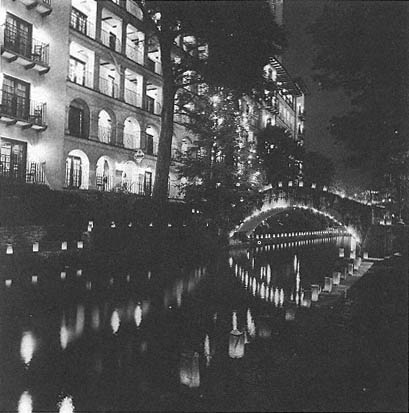

The river in downtown San Antonio, Texas, was not merely reclaimed; it was used as a catalyst to reinvigorate downtown. It is important that the process of rejuvenating riverfront developments did not destroy the very context it was meant to enhance. In some cases, existing buildings addressing the river were merely refurbished. In other instances new developments like the Hyatt and Hilton hotels were pieced into the riverside fabric. At the Hyatt, development created a strong link to the Alamo, thus integrating previously isolated elements of downtown. Larger developments like the convention center and River Center add new elements to the Riverwalk and link the river level to city streets and activities above. River Center, a new shopping complex, ties an existing department store and adjacent city streets to riverside activities. Hence, parts of the city are reclaimed by the intervention of the catalyst. The most common approach, however, was to turn the backs of buildings carefully into river-fronting facades. In most cases this was accomplished while keeping their informal warehouse character.

Finding the value in existing elements of a development like Paseo del Rio is crucial. To recast them would have involved costly artifice. The unique character of the place, so different from that of a commercial downtown, was its central virtue.

In 1985 the city of Phoenix sponsored a competition for the design and planning of a new municipal government complex. Among the objectives were two kinds of effect: to stimulate downtown development and to suggest patterns and attitudes for subsequent design in Phoenix. Many of

the competitors approached the problem as though the complex were self-contained. Their dramatic proposals would produce a focal point, an architectural monument, even, that could capture worldwide attention. The new municipal center would upstage the rest of Phoenix.

Other competitors sought to weave the new complex into the city fabric, to make it integral. This meant retaining several of the existing, still usable, structures on the twelve-block site. It meant respecting the reality of downtown Phoenix, which is not a traditional center city commercial district but largely an area of office structures with only limited retail support. It is unrealistic, these competitors argued, to think that shopping patterns can be changed simply through the introduction of shops as part of the new government center. More reasonable is an approach that attaches the new complex to existing services and retail facilities and provides for incremental growth. This approach, instead of surgically implanting an extensive new complex, would graft new facilities incrementally onto existing ones.

Grafting does not mean the uncritical preservation of what exists. Even a modest intervention necessitates some changes in the existing urban

57.

San Antonio. Buildings fronting the river.

58.

"Grafting" of new elements. Competition entry to the Phoenix Municipal Government

Center by ELS / Elbasani and Logan and Robert Frankeberger, architects. Instead of

upstaging the urban context with an extensive, entirely new complex, this approach

recommends gradually attaching new elements to existing ones in a process that

evolves a new government center rather than implants it. In the plan

(lower part of figure), existing buildings are darkened.

fabric. New and old can mix to produce transformed urban elements. So, for example, competitors proposed that in addition to the historic Dorris Opera House, other buildings in the twelve-block site be refurbished for new use until such time as the city could afford to construct additional government buildings. Instead of planning to clear and build slowly over ten, twenty, or more years, they worked out an incremental strategy to evolve a municipal government center through gradual replacement.

That a catalyst acts moderately, not catastrophically, indicates two values: there is economic value in salvaging existing elements for new uses; and elements with intrinsic urban value continue to enhance the city. It is not necessary to rebuild as though nothing of worth had already been accomplished.

Unfortunately, in an effort to retain the past, historic buildings are too often disfigured and their essential qualities lost. An urban setting can effectively be destroyed even when it is "saved." The practices of patching historical facades as ornaments on much larger buildings and of constructing new buildings to loom over a smaller historical remnant do not

59.

Historical facades lose value and significance when treated as an appliqué on

much larger new buildings.

transform and enhance the earlier elements but emasculate and caricature them. The issue in preservation is not buildings but the spirit of places. A better policy than preservation at any cost, is to seek a new hybrid of old and new.