Appendix

A Letter to My Son

To: Taylor Spight Hines

From: Thomas Spight Hines

Re: William Faulkner and the relationship of the Spight, Hines, and Fa(u)lkner families

18 April 1994

Dear Taylor:

As you have begun to read and admire the work of William Faulkner, you have asked me on several occasions to share with you my personal memories of Faulkner when I was growing up in Oxford, Mississippi, and of the long relationship that our family has had with his. So I am turning to this before my memory gets any dimmer. Consider this a belated eighteenth birthday present.

My earliest sense of Faulkner came from my father's recollections of his and his family's world as it intersected with that of the Falkners in Ripley and Tippah County, Mississippi, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. (For reasons that have never been totally clear, Faulkner added the "u" to the family name in the 1920s.) Throughout my early life, I went back to Ripley with my parents at least two or three times a year to visit relatives, particularly at family funerals, which in rural Mississippi were usually warm and frequently festive occasions. These reunions included primarily branches of the Hines and Spight families, my father's mother, Mattie Spight Hines, having been the daughter of Thomas Spight, a cousin of Holland Pearce Falkner, William's great-grandmother.

These family gatherings included not only people still dwelling in Ripley but far-flung relatives returning there to bury the dead, which means that the now rather dilapidated Ripley cemetery has a vivid place in my consciousness. On the hundreds of occasions I have visited it through the years, from the earliest to the most recent, I have never failed to walk from the Hines and Spight sections southeast to the tall statue over the grave of Colonel William Clark Falkner, William Faulkner's great-grand-father. I recall once when, as young children, we were obviously making too much noise, our Aunt Virginia suggested firmly that we "go over and count the books on Colonel Falkner's statue." The books were granite simulacra, stacked at his side, of the actual books he had written in life.

The best evocation of this scene is from Faulkner's novel Sartoris , in which the character of Colonel Sartoris is largely based on that of Colonel Falkner: He stood on a stone pedestal, in his frock coat . . . one leg slightly advanced and one hand resting lightly on the stone pylon beside him. His head was lifted a little in

that gesture of haughty pride which repeated itself generation after generation with a fateful fidelity, his back to the world and his carven eyes gazing out across the valley where his railroad ran and the blue, changeless hills beyond, and beyond that the ramparts of infinity itself .

In addition to my father, the people who most enriched my sense of Ripley and the Spight-Hines-Falter connection were two women, who in their different ways were both interesting and intelligent people: my great-aunt Nancy Spight, wife of Lindsey Donelson Spight (son of Thomas, broker of my grandmother, Mattie) and, as corrective counterpoint, Aunt Virginia Hines McKinney, my father's sister, who disapproved not only of William Clark Falter and William Cuthbert Faulkner but also of Aunt Nancy herself, who was something of a family rival. Aunt Virginia was, for her time and place, a remarkably liberal Democrat (an avid Rooseveltian New Dealer and an admirer of Eleanor as well), but morally a pious Baptist who was repelled by Sanctuary . Aunt Nancy was less pious, but much more politically conservative; she greatly admired Senator Eastland, and she was an eager, and competent, DAR/UDC genealogist. The enclosed "family tree" is actually from Aunt Nancy's DAR chart, but her findings confirm and emend those of careful and reputable historians. For example, she established the fact that the first American Spight was one Ira Spight, who sailed from London to Virginia in July 1635.

The major Spight-Falkner connections in Mississippi in the nineteenth century resulted from the kinship of my great-grandfather, Thomas Spight, his uncle, Simon Reynolds Spight, and their cousin, Holland Pearce Falter, the first wife of Colonel Falter. The common ancestors of Thomas, Simon, and Holland were Mary Reynolds Spight (1760-1822), a relative of the English painter Sir Joshua Reynolds, and Simon Spight (1741-1816), a quartermaster in the Revolutionary Army. Simon was a cousin of Richard Dobbs Spaight (1758-1802), a signer of the United States Constitution and the third governor of North Carolina. (In those days, different branches of various families spelled their surnames differently.) Simon and Mary Spight lived and died in Jones County, North Carolina, and never saw Mississippi. Their children included Holland Spight Harrison, Faulkner's ancestor, and the first Mississippi Thomas Spight (1779-1857), my great-great-great-grandfather. Spight migrated from North Carolina in 1830 to Gibson County, Tennessee, and along with another of Faulkner's great-great-grandfathers, Abel Vance Murry, was one of the original white settlers of Tippah County after the Chickasaws ceded these lands in the Treaty of Pontotoc (1832). Spight's obituary states that in 1836, the year of its founding, he "moved to this county, then in the occupation of the Indians." One of the witnesses to his will was Richard J. Thurmond, Colonel Falkner's future business partner and assassin.

The Spight and Faulkner lines in question run like this:

1. Simon Spight md. Mary Reynolds. | |

2. Holland Spight md. Simmon Harrison. | 2. Thomas Spight md. Rebecca Mumford. |

3. Elizabeth Harrison md. Joseph Pearce. | 3. James Mumford Spight md. Mary Elizabeth Rucker. |

4. Holland Pearce md. William Falkner. | 4. Thomas Spight md. Mary Virginia Barnett. |

5. J.W.T. Falkner md. Sallie Murry. | 5. Mattie Spight md. William Hines. |

6. Murry Falkner md. Maud Butler. | 6. Thomas Spight Hines md. Polly Moore. |

7. William Faulkner md. Estelle Oldham. | 7. Thomas Spight Hines, Jr. md. Dorothy Taylor. |

(Between the first Simon Spight and the present, there has obviously been one more generation in our family than in the Falkner family, since my father's generation (6) and William Faulkner's generation (7) are obviously of the same age and time.)

In his novel Sartoris , Faulkner has John Sartoris proclaim: In the nineteenth century genealogy is poppycock. Particularly in America, where only what a man takes and keeps has any significance, and where all of us have a common ancestry and the only house from which we can claim descent with any assurance is the Old Bailey. Yet the man who professes to care nothing about his forefathers is only a little less vain than he who bases all his actions on blood precedent (p. 87).

Be that as it may, after the first Simon Spight, the common ancestor, the most important person in the Spight-Falkner connection—the person most responsible for bringing Holland Pearce to Ripley, where she met her future husband, W.C. Falkner, and bore his first son, J.W.T. Falkner—was Holland's cousin, Simon Reynolds Spight, son of the first Mississippi Thomas Spight and grandson of the North Carolina Simon Spight. According to Nancy Spight (in a letter to me, undated, ca. 1955), "Simon R. Spight, on the death of the father, became the guardian of the Pearce children." About the time that Holland Pearce married William Falkner, her brother, Joseph Pearce, married Frances (Fanny) Spight, the daughter of Simon. During these years, Aunt Nancy states, Thomas Spight and his sons James Mumford and Simon Reynolds "owned about 100 slaves." (I recall here, Taylor, that as you began to study American history in the Los Angeles schools, you were rightly shocked and dismayed to learn that you were, alas, a descendant of slaveholders!) Of Simon Reynolds Spight, Aunt Nancy also noted that: "Before the Civil War, there was a flood in Missouri. Levees broke and, without remuneration, he took his slaves and went to Mo. and helped to repair the damage. Many years later, the state of Mo. gave him some land . . . as their appreciation."

The historian Joel Williamson, in his fascinating book William Faulkner and Southern History , observed that "from local records, one can easily pick out the dozen or so clans that formed the elite, the 'aristocracy' of Tippah County and the town of Ripley. . . . Some clans, such as the Spights, maintained both plantations in the country and impressive households in town, and their sons might become lawyers and doctors" (p. 37). Unfortunately, Williamson did not know the actual family relationship of Holland Pearce and Simon R. Spight (as cousins and descendants of Simon Spight), but he wrote an otherwise cogent analysis of the implications of their relationship:

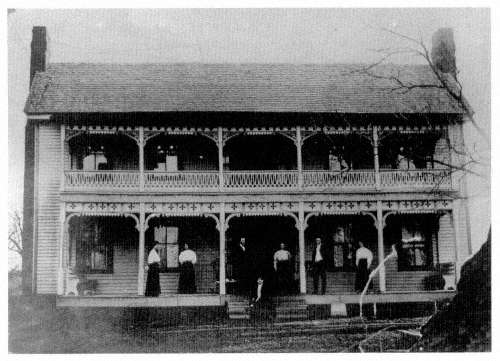

Figure 98

Simon Spight House, Ripley, Mississippi

(1850s and later, demolished; photograph, late nineteenth century).

"Holland Pearce did not come at all empty handed to her marriage. Along with several siblings, she was an orphan who was in the process of collecting a substantial inheritance when she met William. Also, she was in some way connected to Simon R. Spight and his family. Both the Pearces and the Spights were originally from Jones County, North Carolina, a region of wealthy planters and slaveholders in the eastern part of the state. Simon Spight was primarily a merchant and hotel owner in Ripley; but he also owned land and slaves and would become one of the several richest men in the county during the 1850s. Very early in 1847, he became the guardian for Holland and her four brothers and sisters. Holland's father had died without a will in Weakley County, in northwestern Tennessee, leaving a large estate that included twenty-eight slaves" (pp. 18-19).

Williamson then goes on to explain how "Simon Spight undertook the complicated business of settling affairs in Tennessee and moving the Pearce children to Ripley. He bought and sold slaves during the division of property in Tennessee, in one case making a purchase to keep Jim and Rachel and their one-year-old daughter together as a family. Also, he hired people and transportation to move the Pearces, their effects, and their slaves to Ripley, a twenty-seven-day journey by wagon and carriage. In January, 1847, he leased out for the year the employable slaves for $1,088, keeping the unemployables in his own household. During that year, at a cost that exceeded their income, he maintained the Pearce children and saw to their education."

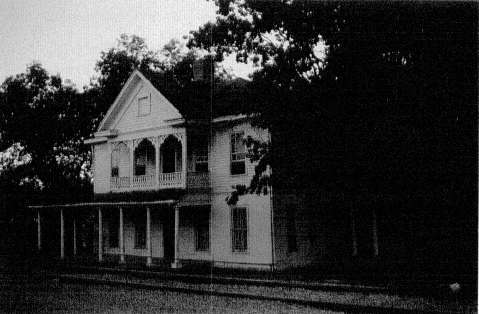

Figure 99

Chesley Hines House, Ripley, Mississippi

(1850s and later, demolished) railroad tracks in foreground.

On July 9, 1847, Holland Pearce and William Falkner were married in Knoxville, Tennessee—the area in which she had lived before moving to Ripley and in which, presumably, she still had relatives. On September 2, 1848, a son, John Wesley Thompson Falkner, was born. Holland died of consumption in the spring of 1849. In 1851, Falkner married Elizabeth Vance, and they subsequently had six children: William Henry, Thomas Vance, Lizzie Manassah, Effie Deane, Willie Medora, and Alabama Leroy, the latter two of whom were later connected to our family and to this story.

The major postwar Hines-Falkner connection involved the splendidly named Ship Island, Ripley and Kentucky railroad, of which Falkner and Richard Thurmond each owned one-third of the stock. Chesley Hines, my great-grandfather, and his brother-in-law, C.L. Harris, my great-great-uncle, owned the other third, Hines owning slightly more than one-sixth. This was significant since Hines usually tended to side and to vote with Falkner while Harris, a kinsman of Thurmond's, tended to side with Thurmond—a situation that usually gave Falkner a slight edge. Chesley Hines (1834-1879) was an enigmatic figure, in some ways not unlike William Falkner, in that (unlike the more established and well-documented Spights), he seemed to "appear" in Ripley as something of a loner. He was born in 1834 in Hardeman County, Tennessee, into a family who had come originally from the Carolinas. At the age of eleven, for reasons that are not clear, he left home, possibly as an orphan, and like Falkner lived for a while with relatives in Missouri, before migrating south to Tippah County in 1852 at the age of eighteen. He did not, amazingly, attend school until he was twenty years old, but was described as "an expert mathematician . . . a natural born mechanic," and a "practical accoun-

tant." In 1858, he married Elizabeth Harris, daughter of the prominent Onie Allen and John C. Harris, originally from neighboring Marshall County. Hines served in the Confederate army and was wounded at Perryville, Kentucky.

Chesley Hines's reputation as mechanic, accountant, and mathematician and, by the 1870s, his increasingly comfortable income made it logical for him to join Falkner's and Thurmond's railroad enterprise, which seems to have gotten under way in 1872. Historian Stewart H. Holbrook, in The Story of American Railroads , observed that Falkner apparently "got to thinking that Ripley, a mere backwoods hamlet to which freight had to be hauled by team, ought to have better contact with the world. Falkner did not have much capital, but he did possess eloquence, which in the South of that day was rated higher than capital, and he had an idea—a railroad from Ripley to tap the Memphis and Charleston at Middleton, Tennessee, twenty miles north. . . . He must have had a winning personality . . . for he got his fellow Mississippians, nearly all of them made poor by the war, to supply cash and other aid in plenty. Some cleared the right-of-way. Others furnished lumber and ties and timbers. Many turned out to lay the rails. Much of this was donated labor. Among those paying cash for stock were the Harris, the Hines, and other well-to-do families, but the heaviest stockholder of all came to be R.J. Thurmond" (pp. 144-45).

Chesley Hines seems to have been the partner most involved in the technical aspects of actually running the railroad. In 1879, he lost his life in an accident while piloting the train when a stray animal suddenly appeared on the track as it crossed a trestle between Ripley and the hamlet of Falkner, causing the engine to overturn. In the crash that followed, Chesley Hines was scalded to death. His widow, Elizabeth Harris Hines, mother of nine children, retained the stock as a silent partner, supplementing her income by transforming portions of the huge Hines house, just west of the train tracks and across from the depot, into the Ripley Hotel. Richard Thurmond was a bondsman for the estate. Later, Chesley's son William, my grandfather, worked as an engineer on the railroad and had the eerie experience of spotting an animal sauntering on to the tracks very near the spot where his father had been killed. Fortunately, he was able to stop the train in time to avoid his father's fate, but my father remembers him saying that, in his fright, his hair "stood up" beneath his cap.

This is not the place to go into the evolution of the Falkner-Thurmond feud, since it is ably analyzed, from different perspectives, by such scholars as Andrew Brown, Joseph Blotner, and Joel Williamson, except to say that my father remembers hearing the oft-noted contention, both in his family and out in Ripley, that one of the sources of friction involved questions about Elizabeth Hines's stock and her share of the dividends. My father's sense was that Falkner had sided with the widow Hines and had possibly insinuated that Thurmond, as one of the bondsmen for Chesley Hines's estate, had not treated her fairly. This is somewhat confirmed by Andrew Brown in his judicious History of Tippah County Mississippi (p. 292). In documenting one of the public confrontations between Falkner and Thurmond prior to their final encounter, Brown quoted an eyewitness to the effect that "while Thurmond was talking to a group in the courthouse yard, Falkner walked up to him, thrust his hands into the armholes of his vest, and said, 'Well, here I am Dick. What do you want of me?' Thereupon Thurmond lashed out with his fist, knocking Falkner down. The infuriated Colonel rose to his feet and launched into a long tirade in which he accused Thurmond, among other things, of being a robber of widows and orphans. . . ." Whatever the prelude, the causes or motivations, the fact is that on November 5, 1889, Falkner was shot by Thurmond on the Ripley square, while talking with his friend Thomas Rucker, a cousin of Thomas Spight. He died the next day.

Indeed, in the latter part of William Falkner's life, Thomas Spight played as significant a role as his uncle, Simon Spight, had done in the earlier period when Falkner married Simon's cousin and legal

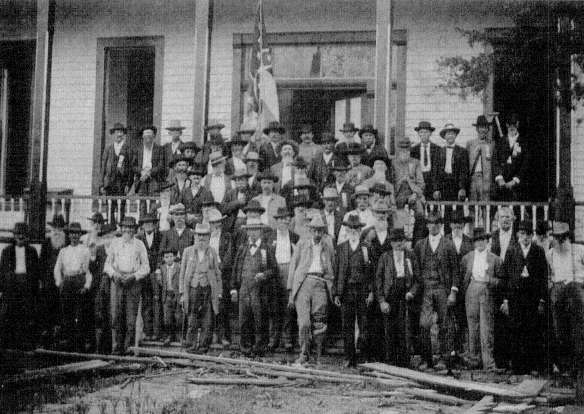

Figure 100

Tippah County Confederate Veterans Reunion, Company B, 34th Infantry Regiment, Walthall's Brigade, C.S.A., Ripley,

Mississippi (1904). Thomas Spight, Company Commander, front row, 5th from left, under flag; Ripley School in background.

ward, Holland Pearce. Like his grandfather and namesake, the first Mississippi Thomas Spight, and like Simon Spight as well, the second Thomas Spight (1841-1924) was, if not a prototype, a least a person who predicted and suggested certain clearly discernible aspects of later "Faulknerian" literary characters.

Thomas was born into what Blotner calls a "prominent" family and Williamson an "elite" family, the son of Mary Elizabeth Donelson Rucker and James Mumford Spight. He grew up in Ripley and on the Spight plantation east of town. He was a beginning student at La Grange Synodical College, La Grange, Tennessee, when the war began in 1861. Leaving college with his valet-factotum and lifelong companion Tucker Spight, a black slave of roughly his own age, "given" to him early in his life, Thomas Spight entered the Confederate army as a third lieutenant. Before he was twenty-one, he had advanced to the rank of captain, Company B, 34th Mississippi Infantry, Walthall's Brigade, a military experience that reached a fateful apex in the Battle of Atlanta, 1864, in which he was wounded. "Tuck" Spight apparently was crucial in saving his life by pulling him from the thick of battle into a nearby wood and getting medical aid for him. With Tuck at his side, he surrendered with his command at Greensboro, North Carolina, April 1865. For the rest of his life, Captain Spight, as he was thereafter known, walked with a limp and carried a cane. Tuck Spight accompanied him to the annual Confederate veterans reunions. Both men claimed, more than half seriously, that Tuck should be officially considered a "Confederate veteran."

After the war, Spight, "land poor" like most of his family, returned to Mississippi, first to farm and then to study law and begin his practice. In 1865, he married his first cousin, Mary Virginia Barnett. His and his wife's mothers were sisters, the daughters of Nancy Ann Kavanaugh and Henry Tate Rucker. Spight was one of the first former Confederates to get elected to the Mississippi House of Representatives (1874-80), where he was instrumental in the impeachment of the "carpetbag" governor Adelbert Ames. (Later in Washington, as a member of Congress, Spight's desk was next to that of Adelbert Ames's son.)

Following his legislative years, Spight resolved to continue his political career on a larger scale and, to this end, in 1879 he founded and became editor of the Ripley Southern Sentinel . He continued as editor until 1884 when he was elected district attorney, a post he would hold until 1892. The paper, which he continued to own and over which he maintained a paternalistic interest, would become one of the best weeklies in north Mississippi and would be especially valuable as the major documentary source for recording the life and development of Tippah County. Spight also used it to publish, serially, the last book of William Falkner. In 1883, a year after the publication of his novel The Little Brick Church and two years after the appearance of his most famous work, The White Rose of Memphis , Falkner decided to travel to Europe with his daughter Effie, and beginning with his arrival in New York, he began keeping a notebook of his experiences. He sent these notes back in the form of letters to his friend, Thomas Spight, and Spight published them in the paper in weekly installments—much as the rival Ripley paper, The Advertiser , had serially published The White Rose of Memphis . Upon his return, Falkner revised and expanded the sketches into a book he called Rapid Ramblings in Europe , which Lippincott published in 1884. In its drolly humorous picture of Americans in Europe, it resembles Mark Twain's Innocents Abroad . I have the copy of the book that Falkner presented to Spight.

By this time, the Spight and Falkner homes were diagonally across from each other. Thomas Spight's house, called "The Magnolias" after the large trees in front, faced Union Street between Cooper and Pine and was a Victorian remodeling of an older house that had been in the Spight family for some time. Falkner's more wildly eclectic "Italian villa" indeed reflected, with its overscaled Mansardie

Figure 101

Falkner House, Ripley, Mississippi (1884, demolished;

photograph ca. 1900), view from front yard of Captain

Thomas Spight, his daughter, Lillian Spight, in foreground.

tower, his own "rapid ramblings in Europe." Occupying the whole block between Union, Cooper, Mulberry, and Main streets, it too was a remodeling of a smaller, older house. Between these two houses on the block facing Cooper, between Union and Main Streets, was the house Falkner built for his daughter Willie Medora and her husband, the physician N. G. Carter. While "The Magnolias" would continue to be occupied into the mid-twentieth century by Spight's unmarried daughters, Allie and Mamie, the Falkner and Carter houses would be sold to two of Thomas Spight's other children, Falkner's cousins-by-marriage: his own to Lindsey Donelson Spight, my father's uncle, and the Carter house to William and Mattie Spight Hines, my grandparents. More on the Carter-Hines house later.

Despite the kinship and friendship, however, there were sometimes tense moments between Spight and Falkner. In one of her letters to me in the mid-1950s, Aunt Nancy recalled, of Captain Spight, that: "One time he and Col. Falkner were arguing a case, and Col. Falkner called him a liar, it was said; there was a table between them and Capt. Spight jumped over but friends caught them before there was a fight. He went home to dinner and before he went back there was a note brought to him from Col. Falkner apologizing, which it seems was a compliment to both men. Col. Falkner was a hot head, I have always understood, and he must have had respect for Capt. Spight to apologize." Aunt Virginia also passed on a story about this incident to the effect that Spight's wife, my great-grand-mother, Mary Virginia, was so outraged by Falkner's accusation that in the hours between the confrontation and the apology she burned the first editions that Falkner had given them of The White Rose of Memphis and The Little Brick Church .

In the late 1880s, however, the Spight-Falkner relationship took on a new dimension as the Falkner-Thurmond relationship deteriorated. "Thurmond wanted only to be left alone," Andrew Brown contends, "though he was determined to defend himself if he thought his life was in danger. Falkner's attitude seems to have been one of fatalism. Late in 1889, he told Captain Spight, in the manner of one merely stating a fact, that Dick Thurmond was going to kill him, and asked some questions about preparing his will. Spight suggested that Falkner carry a gun for self-defense, but the Colonel refused to do so, saying that he had killed two men already, and had rather die himself than slay another" (pp. 292-93). Spight advised Falkner and probably made notes or a draft of the will that was written and witnessed in Memphis on October 25, 1889.

Though accounts of motivations and circumstances vary widely, Thurmond shot Falkner on the Ripley square on the following November 5th. Since his wife and younger children were not at the "villa" but in Memphis, and likely because his son-in-law was the town physician, Falkner was taken to the home of his daughter, Willie Medora Carter, across the street. There he died the following day The funeral was at his wife's Presbyterian church, though Willie Carter latter commissioned a stained glass window for her own Baptist church, which the Baptists declined to install, ostensibly because Falkner was not a church member. Aunt Virginia claimed that Thurmond partisans threatened to destroy it if it were placed in the church. According to Brown, Mrs. Carter "finally placed it in the sitting room of her home, later known as the William Hines place, cutting through the back wall to make a place for it. It remained there for many years, long after the Carters had left Ripley" (p. 302). I can remember long ago seeing the window after the house was sold and no longer belonged to my family.

After the shooting, Thurmond was promptly jailed and indicted, but due to defense counsel's delaying tactics and to the general consensus that a cooling-off period was needed, Thurmond's trial for manslaughter did not begin until February 18, 1891. According to various witnesses, Thomas Spight, the district attorney, prosecuted the case vigorously. My grandfather, William Hines, was summoned to be a juror and then was dismissed because of a conflict of interests: he had just become engaged to be married to Spight's daughter Mattie. Thurmond hired the best criminal lawyers in the state to defend him, though the Falkner partisans also claimed that he used his vast wealth to "buy off" potential jurors as well. In any case, after a tense and complex trial, Thurmond was acquitted.

In 1892, Thomas Spight returned to the private practice of law while making plans for higher political office. In 1898, he was elected to Congress and remained there through the administrations of McKinley, Roosevelt, and Taft, being defeated for reelection in 1911 by supporters of the Populist James K. Vardaman. Though Spight's views on the race question seem conservative in retrospect, he was considered in his day to be left of center in such matters, having refused, for example, to join the Ku Klux Klan.

If not a great national leader, Spight was considered a distinguished Southern congressman. Yet nothing on the national agenda apparently seemed more important to him or took a higher priority than promoting Confederate veterans' affairs and unveiling and dedicating Confederate monuments. He dedicated the monuments in Ripley and Oxford, for which I still have manuscript copies of his rather impassioned speeches. While Spight was a member of Congress, he and his family had an apartment at the Willard Hotel. After leaving Washington, he returned to practice law in semiretirement in Ripley. One afternoon, after his lunch and nap, he returned to his office on the square and was baffled to find the street department taking down his Confederate monument. He did not understand that the roadway around the square was simply being improved and that the monument was going to be returned to its rightful place, but in his astonishment, he had a stroke and died. It was the end of a strikingly symmetrical life—for the Confederacy.

The house of Willie Medora Carter, in which Colonel Falkner died, would provide a small but poignant memory for her great-nephew, William Fa(u)lkner, born in 1897 in New Albany, Mississippi, where his father was working for the family-owned railroad. In 1898, the family moved back to Ripley, where they lived on Jackson Street until 1902, when they moved permanently to Oxford. The incident involved a childhood visit of William to his Aunt Willie's house two blocks away and was recalled in a letter he wrote from Paris, September 10, 1925, to his Aunt Bama McLean, Willie's sister, a letter that noted an anticipated visit with his cousin, Willie's daughter, Vance, called Vannye. I will be

Figure 102

Carter-Hines House, Ripley, Mississippi (1884, demolished).

awfully glad to see Vannye again , he wrote The last time I remember seeing her was when I was 3, I suppose. I had gone to spend the night with Aunt Willie . . . and I was suddenly taken with one of those spells of loneliness and nameless sorrow that children suffer, for what or because of what they do not know. And Vannye and Natalie brought me home, with a kerosene lamp. I remember how Vannye's hair looked in the light—like honey (Blotner, Selected Letters , p. 20).

My parents also passed on to me a story that Grandmother Hines had told them, which was confirmed and emended for me in the late 1950s by Faulkner's mother, "Miss Maud." Sometime during the years when Murry and Maud Falkner and their children lived in Ripley, my father's older brother, William Hines, and William Fa(u)lkner, a distant cousin and playmate roughly the same age, went off one afternoon to play together. At sunset, the two small boys had not returned and the families became rather worried. After cursory searches had revealed no boys, a formal searching party was organized and the two young Williams were found inside an old culvert, sound asleep, apparently exhausted from the day's play. Miss Maud said that she would never forget the anxiety she and my grandmother felt in the belief that something terrible had happened to their two oldest sons. I don't know how much the years added to the "awesomeness" of this incident but, on the other hand, the world might owe a lot to that searching party. Aunt Virginia, who was frequently a playmate of the two Williams,

also recalled that her brother, William Hines, had a toy goat that made a noise that William Fa[u]lkner was afraid of. Whenever William H. would frighten William F. with the goat, the latter would go to my grandmother and say, "Miss Mattie, make William put up the Billy Goat."

When the Carters left Ripley in 1901 or 1902, they sold their house to my grandparents, William and Mattie Spight Hines. My father always seemed very proud of the fact that, in 1906, he was born in the same room in which Colonel Falkner had died. My grandmother lived there until her death in 1936, after which the house was rented for several years and then sold. In the 1960s, the current owners resold the land for commercial development, and this large, two-storey house was moved out into the country, east of Ripley, where, I am told, it became a crossroads store and "honky-tonk" before it burned several years later—a sadly ironic and, I am tempted to say, "Faulknerian" sequence of events.

My father grew up in Ripley, graduated from Ripley High School in 1923, received his B.A. degree in history from Mississippi College in 1927 and his M.A. degree in Latin from the University of Mississippi in 1935. After college, he taught Latin and History and coached football at Oxford High School, during which time he was a colleague of Dorothy Oldham, Estelle Faulkner's sister, who would become a lifelong friend. In the early 1930s, he moved to teach at Webb, in the Mississippi Delta, where he met and married my mother, Polly Moore, in 1932. They then returned to Oxford, where he continued to teach and coach at the renamed University High School, teaching there both Malcolm Franklin and Victoria ("Cho-cho") Franklin, children of Estelle Faulkner from her first marriage to Cornell Franklin. The Faulkners hosted several school parties and graduation functions for their children at their home, Rowan Oak, which my parents attended. My father recalled talking with Faulkner there and on other such occasions about Ripley and their various family connections.

My mother in those years also belonged to the same bridge club as Estelle Faulkner and recalled with a kind of bemused, mock horror that one afternoon when the club was meeting at Rowan Oak, with the ladies "dressed-up" in proper 1930s Oxford bridge-playing attire, William rather "shocked" (or titillated?) the clubmembers by "walking through the house not wearing a shirt!" Despite the Nobel Prize and his other considerable achievements, this remained throughout the years my mother's dominant image of the greatest writer of our century. My mother was fond of Estelle Faulkner, appreciating her warmth and vibrancy and her intense, "expectant" quality, and she observed once that Estelle "always looked as though she had just been rather surprised by something."

In 1936 when I was born, my parents lived on Fillmore Avenue in a small brick house that faced north but that backed on to open land leading into Bailey's Woods, a tract that Faulkner owned and that led south to Rowan Oak. Separated by these woods, Faulkner's grand house and my parents' modest bungalow lay less than a mile apart. In that same year, in Oxford and Los Angeles, Faulkner completed Absalom, Absalom ! which was published on October 26. I was born two days later on October 28. So, Taylor (if you will indulge me here in a bit of hubris), it has always pleased me to recall that Absalom and I were gestating a short distance apart at exactly the same time. Absalom, Absalom ! is much, much more important than I am, and it is surely my favorite Faulkner novel for reasons that are larger than the simultaneity of our births. Yet I enjoy remembering that I was born in good company.

After completing his master's degree, my father was faced with a choice of whether to go elsewhere to pursue a Ph.D. in classics and history or to stay in Mississippi and to continue, as teacher and administrator, to make whatever contributions he could to Mississippi public education. He chose the latter path, of course, with, I believe, considerable success in very difficult times, but I wonder

sometimes if he should not have chosen the other option since he was undoubtedly a splendid teacher and had enormous, if underdeveloped, talent as a writer—talents that might have brought him more satisfaction, and certainly more approbation, than he received in the career he chose. In pursuit of that vocation, however, he left Oxford in 1937 to become superintendent of the schools of Como, Mississippi—an event of considerable importance to you, Taylor, since one of the first teachers he hired (and introduced to the town's most eligible bachelor, Ernest Taylor) was your future grandmother, Dorothy McGee. While in Como, my father remembered, he saw William Faulkner only once—at a barbecue given by Don and Maybelle Bartlett, your grandfather Taylor's first cousins. As before, my father recalled, he and Faulkner talked about Ripley as well as about Malcolm and Cho-Cho.

In 1940, TSH was offered a better and more demanding job as superintendent of the larger school system of Kosciusko in Attala County, Mississippi, where we lived for twelve years. There, among other old Kosciusko natives, we knew the Niles family, related to Estelle Oldham Faulkner. Through this connection, Faulkner must have become acquainted with aspects of the history and the character of Attala County, which while different in some ways from Tippah and Lafayette counties in north Mississippi, still has many resemblances to that "mythical" composite that Faulkner called "Yoknapatawpha."

The years we spent in Kosciusko during the forties and early fifties were the years when we returned most often to visit relatives and friends in Ripley and Oxford, and it was sometime in this period that I remember being in Memphis with my parents and going with my father to pay a visit to "Miss Bama" Falkner McLean, whom he had known all of his life. I must have been in my early teens because I had just finished reading Intruder in the Dust , and I was awed by the fact that this grand but friendly woman was the daughter of Colonel Falkner. I recall that she and my father talked about Ripley, of course, and that she spoke warmly not only of my grandparents but of my Spight and Hines great -grandparents. I remember thinking she was an ancient relic then, but she lived on, incredibly, until 1968, dying at the ripe age of ninety-four.

In 1952, my father was offered the position of Director of Admissions at Ole Miss, and we moved back to Oxford. Later, he became Director of Student Activities, a job he held until his retirement in 1972, the year before his death. I attended University High School for my junior and senior years and recall first seeing William Faulkner walking up North Lamar Street to the square, where he would frequently stand alone, smoking his pipe and looking into the distance. At other times, less often, I would observe him talking quietly to someone. The first time I remember actually meeting him and speaking with him was probably during my junior year in high school when his step-granddaughter, Vicki Fielden, Cho-Cho's daughter, visited the Faulkners with a roommate from school, and my friend and classmate William Lewis and I were asked to take them out. On this and the several other occasions when we did this, Faulkner would receive us and talk with us for the minutes we were waiting for the girls. I also remember that once the Faulkners hosted a dance for Vicki in the ballroom of The Mansion, a downtown restaurant. Both of them attended and were in good form. Sometime later when I ran into him once in the Kroger grocery store downtown, I asked him what he had heard from Vicki, who at that time had acting aspirations. "Vicki writes," he said drolly, "that she has a part in a play Off Broadway. But from what I can tell, it's pretty far off Broadway."

In the fall of 1954, I entered Ole Miss and met a fellow freshman from Little Rock, Arkansas: Dean Faulkner, the daughter of William's deceased younger brother, Dean, who had been killed in 1935 in a plane crash near Oxford, several months before his daughter was born. From that time on, William

had assumed the role of avuncular, if unofficial, guardian. Dean called him "Pappy." Most of the rest of us called him Mr. Faulkner. It was, in fact, during my Ole Miss years, as a result of my being a classmate of Dean's, that I was privileged to be with Faulkner on a number of occasions, chiefly at Rowan Oak when Dean had parties there. Sometimes these gatherings were held while WF was away at the University of Virginia and while, I believe, his sister-in-law, Dorothy Oldham, was living at Rowan Oak as hostess and custodian. During our senior year, in the spring of 1958, when Dean became engaged to Jon Mallard, the Faulkners hosted a number of events to celebrate the occasion.

The timing, and the distinction between, these social events are now somewhat blurred in my memory, but I have no trouble recalling the specific conversations I had with Faulkner—mainly because by that time I had become such an admirer of his work and was so frankly awed by him and pleased that I was having a chance to talk with him. Because of this, I was also becoming more intrigued with the Ripley connections, though I was then much less knowledgeable of the details than I would later become. I regret, in retrospect, that we somehow never really talked about Ripley. Also, at that time, I had not yet read Light in August , and my greatest regret is that I did not know to ask him why he had chosen to give the noble name of Hines to one of his most despicable characters.

From those random occasions in the mid and late 1950s when I talked with William Faulkner, I recall the following exchanges: Once when I went to say good night and thank him for the evening, he replied with friendly mock-astonishment: "Well, Tom, I am sorry you are leaving; I didn't realize we were out of liquor." I also recall with particular vividness the engagement party he gave for Dean and Jon in the garden at Rowan Oak when he stood with them on the east porch and made the only truly "Faulknerian" speech I ever heard him make. It recalled phrases and sentiments of other statements of his that I had read or heard on taped soundtracks, including echoes even of the Nobel Prize address. I remember Faulkner's version of that ancient meditation on youth and age to the effect that ". . . those of us here with a lot of white hair and maybe even a little more wisdom as a result of the white hair, admire and envy your youth and energy and optimism even if you don't yet have the wisdom that you will get later. . . ."—or something like that.

Following a Saturday morning brunch at Rowan Oak just prior to Dean's wedding, as we prepared to leave for an Ole Miss football game, I reminded Mr. Faulkner that we had extra tickets and urged him to join us. "Well, thank you, Tom," he replied, in declining the invitation, "but I've never liked professional football or amateur show business."

I also recall that at one of the wedding functions, I had a good visit with Lucile and John Faulkner, William's brother. John was a long-time acquaintance and golfing partner of my father's. And on that particular occasion, he was especially cordial and voluble and talked at length about Ripley, his birth place, and about the several generations of my family he had known there. The night before the wedding, following the rehearsal dinner—since Jon Mallard had no headquarters in Oxford—I of fered my apartment, beneath my parents' garage, as the site for the obligatory "bachelors' party." About twelve of Dean's and Jon's male friends and relatives were present, including William Faulkner, who drove over with me as we preceded the other guests.

As I was preparing the bar, I rather matter-of-factly put a record on the phonograph, which must have struck him as inappropriate for this manly occasion, and I will never forget his firm request to "please turn that thing off." Faulkner had apparently decided not to drink at most of these social events, but here I recall he did have a glass of bourbon, and perhaps more than one. For this, or for other reasons in the spirit of the occasion, he became more talkative than I had ever heard him and I seem to recall that, in one round of rather rowdy joke-telling, he also told a funny joke, the gist of

which neither I nor anyone else who was present could remember later—since the rest of us had far, far more to drink than he did. I regret to say that while I recall having a very good time, I remember nothing else about the evening.

Following the wedding and graduation and Dean's departure from Oxford, and before I left the next year to go into the Army, I had several pleasant and interesting encounters with Mr. F. I had thought that after the Army I wanted to get a Ph.D., but I was not certain yet that I really wanted to spend my life teaching and writing history, and so I decided to take a year's deferment, do a master's degree at Ole Miss, teach a freshman survey course and see how I liked it before making a full commitment to graduate work elsewhere. I did a master's thesis on the movement in Mississippi to repeal the states's prohibition laws in the twenties and thirties, and I discovered in my research that, in the early 1930s, Faulkner had been a member and even an officer of a pro-repeal organization, called The Crusaders. One evening I saw him downtown at The Mansion restaurant, where he was having dinner, and I asked him to tell me what he could remember about The Crusaders. He replied that frankly he could not remember very much about that noble effort except that it was clearly something he had gotten excited over and "signed my name to one hot summer night over a bottle of gin." He also mused, in those still "dry" days in Mississippi, that The Crusaders had obviously not been immediately successful.

In that same year at Ole Miss, I had been elected president of a history student honor society, the Claiborne Society, and had announced to my faculty mentors, James Silver and John Moore, that I intended to ask Faulkner to speak to the group on some rather grand topic like "the relationship of history and fiction." They laughed politely at my naivete and warned me not to be disappointed when he said no. Silver had apparently invited him to speak to students a number of times without success. But I still went confidently down to Rowan Oak to invite him anyway. He came to the door, greeted me cordially, and we sat on his front porch and discussed the matter. He asked about the size of the group, and I assured him it would be small. We then talked about potential times and locations, and lo and behold, he said yes. He wanted minimal publicity and assurance that there would be, for the most part, only students there, and since the event was to take place several months hence, he asked me to come back the week before and remind him personally since, he warned me, he frequently did not answer the phone. I agreed to do that and to come for him the day of the talk and drive him to the campus.

Back at Ole Miss, Silver and Moore were somewhat flabbergasted, but impressed that I had been able to get him to agree to speak. We made modest arrangements for the event and I went back the week before it to remind him and to make final arrangements. He answered the door, seemed somewhat distant and distracted, and when I mentioned the talk, he said: "Oh, yes. . . . Well, Tom, I'll have to ask you to give me a rain check this time. I'm working now, and I can't stop for this." I was, of course, dejected and was chagrined to think of having to tell my mentors what had happened. They, in their wisdom, were not surprised. I realized only slowly, of course, that when he told me he was "working," he meant that his writing was going well. Since this was 1959, he was probably working on The Reivers . For me, it was another interesting glimpse into his world even if it meant no talk to the Claiborne Society.

One of my greatest pleasures in Oxford in the 1950s was getting to know Faulkner's mother, "Miss Maud," who had been a friend of my grandmother's in Ripley in the early twentieth century. When I knew her, she was in her mid-eighties. After Dean left, during the last year I was in Oxford, I became Mrs. Falkner's library courier, stopping by every week or so to visit with her and to return or deliver

the books that she had asked me to check out for her from the Ole Miss library. Blotner's edition of the Selected Letters (p. 442) includes a brief mention by Faulkner of my and his mother's book-swapping relationship. During that year, Maud Falkner was reading through the Russian giants, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, and Turgenev. She spoke very knowledgeably and enthusiastically about her literary interests, including the work of William Faulkner and his critics, about which she was richly informed. She delighted in finding errors in the critics' pieces. One of these had identified Maud Falkner as William's grand mother. Though she usually spoke quietly, her voice rose as she laughed at that. "Of course, William Faulkner is over sixty years old," she said, "and when anyone speaks of Faulkner's mother, people say: 'Faulkner's mother ? Is she still alive?' But now this man is trying to make me even older than I am."

As an avid reader and as a loyal mother, she also admired the comic talent of her son John, particularly his novel Men Working , and she regretted that his fate of standing in the shadow of his brother made his work less appreciated than she felt it should have been. She also enjoyed popular best sellers. Once when we were discussing some high literary matter, she paused, smiled, and asked if I could guess what her favorite "bedtime novel" was. "Promise you won't tell anybody," she said. "It's Herman Wouk's The Caine Mutiny !"

Mrs. Falkner was also a good, amateur, small-town painter, and when I went by to say goodbye to her as I left Oxford in early 1960, she gave me a variant of a portrait she had done of an old black man in Oxford named "Preacher Green." An earlier variant hangs at Rowan Oak and was much loved by Faulkner. Maud Falkner was a warm and wise person, whose sophisticated intellect has never been sufficiently appreciated even by the most gifted Faulkner interpreters. Occasionally on my weekly visits with her, I would encounter Faulkner, coming or going. He and she were clearly devoted to each other and owed each other considerable debts. He was concerned about her living alone and he asked me one day when we met at her house if I would try to find an Ole Miss graduate student who might be willing to stay there for room rent and be available if she needed anything. I found the ideal candidate, a mature, unobtrusive graduate student in English whom Faulkner approved. Yet when he broached this to Miss Maud, she firmly declined the proposal. As fiercely private as Faulkner himself was, she remained independent to the end. She died in 1960, less than a year after I left Oxford.

Shortly before I left, I drove out to Sardis Lake one cold winter afternoon and passed Faulkner returning in his jeep. We waved to each other. In 1962, I was stationed in Germany but vacationing in Luxembourg when I read of his death in the International Herald-Tribune . Shortly before that, my parents had seen him and talked with him briefly at a party at Bill and Mary Moore Green's; he had fallen from his horse and was clearly not feeling well. When I read of Faulkner's death and then received clippings from my family about his funeral, I recalled that, sometime in the 1950s, I had overheard my parents talking about where they wanted to be buried. Should it be in the Ripley cemetery with all the Spights and Hineses or in Oxford where they planned to live the rest of their lives? They decided on Oxford, and my father went down to the courthouse to purchase a plot. When he returned, he said, "Well, guess who I ran into at the courthouse doing the same thing I was doing? William Faulkner!" They apparently spoke, with appropriate levity, about this fateful step they were both taking. Several generations of Faulkner's family had, of course, been buried in Oxford, but the original plot was filled and WF was assigned another one for his own family in the newer part of St. Peter's. Faulkner had arrived at the clerk's office first and was leaving as TSH arrived. Since my father was next in line, he was assigned, in good bureaucratic fashion, the next plot due east of the Faulkners. Both of my parents' graves are there now, along with that of my younger sister Polly Pope Hines, who

died in infancy and whose grave was removed to Oxford from Ripley, where she was first buried in 1941. Sally and I will someday be buried there with them. As with Absalom, Absalom ! I will again consider myself in good company—for eternity.

After I left Germany and the army in 1963, I spent five years working for my Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. There and at UCLA, where I started teaching in 1968, I felt, with the exception of family and close friends, rather disaffected from Mississippi culture, a distancing that probably also tempered my earlier enthusiasm for Faulkner. It was only in the 1980s, when Ann Abadie, at the Ole Miss Center for the Study of Southern Culture, asked me to lead a Lafayette County architecture tour at the annual August Faulkner conference and then later to develop a lecture on "The Architecture of Yoknapatawpha," that I got really interested again in Faulkner and his world—my world. This overly long letter should prove to you that I am clearly still interested, perhaps more than "interested," in this complicated place, the American South. Faulkner's art, of course, while getting at the South more trenchantly than anyone else has ever done, goes far beyond it (as he uses it metaphorically) to embrace and interpret what he himself once called "the comedy and tragedy of being alive." I will follow with interest, Taylor, your own journey through Yoknapatawpha, and hope that these words will interest you.

Love, Dad