Part II: The Dissemination of An Imperial Modernity

The Ottoman Province of Trabzon

3. Horizons

Markets and States

Topography and Environment

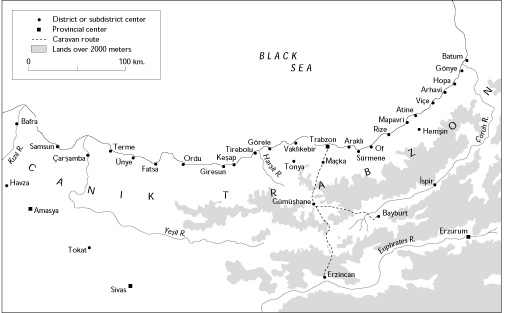

The Pontic Mountains run from west to east across the upper tier of the peninsula of Asia Minor.[1] The northern slopes of these mountains comprise a well-watered coastal region with a temperate climate. The southern slopes belong to the more arid, less vegetated, hot-in-summer, cold-in-winter interior highlands of Anatolia. This contrast between coast and plateau intensifies as the mountains rise from west to east (see map 2).

Map 2. Lands of Canıık and Trabzon (early nineteenth century)

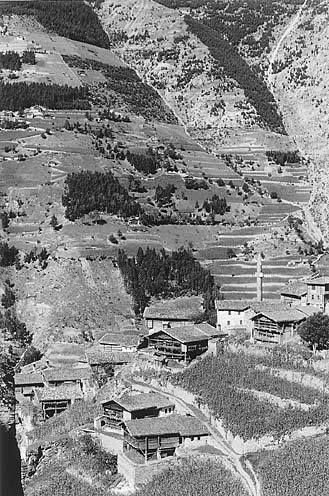

Along all the eastern segment of the coastline, from Ordu to Hopa, there are no large deltas, flat coastal strips are more infrequent and narrower, and the landscape is almost everywhere broken and precipitous. In the foothills near the shoreline, little hamlets with half-timbered houses pepper the foothills, sometimes barely visible among the trees and brush. Around each hamlet there are maize and bean gardens prepared by hand rather than by plough.[2] Away from the shoreline in the upland valleys, the rainfall gradually decreases, the valleys are more deeply cut, and the mountains become steeper. Here the houses, almost always timbered, are sometimes clustered together on a promontory or in a valley, sometimes dispersed across the face of a mountainside (see fig. 6). The villagers are therefore forced to construct narrow terraces on the sheer mountainsides for their maize and bean gardens, sometimes securing themselves with ropes to tend them.

Figure 6. Wooden houses in the high mountains.

Owing to the uneven landscape, level cropland and open pasture are at a premium.[3] To this day neither animal power nor machine power has ever been widely used in agriculture in the region. Along this section of the coast, nothing more than a meager living can be extracted from farming and herding. Farming is usually limited to horticulture. Herding is usually limited to a few cows. Large estates have always been the exception rather than the rule. Nonetheless, some of the area's inhabitants are able to become something other than subsistence farmers and herders, given the rela-tive absence of landlords and overseers. Leaving their garden farms to the care of women, the men of the eastern coastal region can look for work elsewhere in towns and cities of Anatolia.[4] As a consequence, the residents of this entirely rural area have always included impressive numbers of soldiers, teachers, merchants, craftsmen, sailors, fishermen, peddlers, and laborers.

As one moves from the west to the east, the high Pontic peaks gradually come to define an "island on the land," set apart from the remainder of Asia Minor.[5] East of the vicinity of the town of Trabzon, the littoral is not so much a greener version of Anatolia, but another kind of world altogether. Streams and rivers running north and south divide the entire eastern region into side-by-side valley-systems separated by densely vegetated foothills, falling and rising hundreds of meters to and from the water courses. Moving from one valley to another is often impractical owing to undergrowth and ravines. Instead, one must descend to the coastline, travel along the narrow shore, and then ascend into the next valley. Not so long ago, such a trek had to be made on foot or by horse. For lack of roadways, not even a cart could make its way through the foothills or across the rocky beaches. So it is that townsmen jokingly claim that the villagers did not learn of the invention of the wheel until the arrival of motor transport.

By contrast, the farming and herding world across the Pontic mountain chain is entirely different in character.[6] The landscape is open and treeless, sometimes rocky and barren. Winters are cold. Summers are hot. Dry-farming (wheat and barley), stream irrigation (rice and vegetables), and goats and sheep (yogurt and cheese) are the basis of subsistence agriculture. Ploughs and carts are pulled by draft animals. Houses are constructed of mud bricks. Timber, being scarce, is used only for the roof poles, doors, and sashes. Until recently, the only fuel was cattle dung, which was molded into patties (tezek) and dried in the sun. Highly efficient ground ovens (tandıır) are the means for both cooking and heating.

To the north and south of the Pontic chain, rural life is governed by contrasting requirements and possibilities. Crops, flocks, tools, building materials, house designs, kitchen fuel, diet and cuisine, dress and manners, bodies and faces, accents and dialects are different. And some time ago, for a span of centuries, language, religion, and state were also not the same.

Ethnic Fragments and Linguistic Archaisms

Following the Byzantine defeat at Manzikert in 1071, Turkic pastoral peoples began to enter and occupy many sections of Asia Minor, changing the character of its villages and towns. By the thirteenth century, the interior highlands of northeastern Anatolia had been under Turco-Islamic rule for more than a century, and a majority of the population had become Turkish by language and Muslim by religion.[7] This transformation had not always come about with the displacement of the older Byzantine peoples. In many places, groups of Greek-speakers and Armenian-speakers had gradually assimilated themselves to the newcomers, first losing their languages to acquire Turkish, then losing their religion to become Muslim.[8] In contrast, the older Byzantine peoples of the eastern littoral were neither Turkicized nor Islamized until a much later date, and then by a different path.

The eastern coastal region, first as the province of Chaldia in the Byzantine Empire (until 1204), then as the Greek Empire of Trebizond (until 1461), had for a long while remained outside the orbit of the Turco-Islamic states of the interior highlands. Finally capitulating to Sultan Mehmet II, this last mainland fragment of Byzantium subsequently reemerged as the province (paşalıık) of Trabzon. For more than a century, most of the older Byzantine peoples remained relatively unaffected by incorporation. Then, during the course of the second century of Ottoman rule, as a consequence of both conversion and immigration, the large majority of the inhabitants became Muslim. Even so, substantial numbers of the Muslims, most of them descendants of the older Byzantine peoples, continued to speak mother tongues other than Turkish. The eastern coastal region therefore stands as an "exception" twice over to what had happened in the interior highlands.[9] A Muslim majority did not emerge until the seventeenth century, almost four hundred years after the rest of northeastern Anatolia. And when this Muslim majority did emerge at last, its constituents spoke a variety of languages, such as Turkish, Lazi, Greek, and Armenian.

As both Anthony Bryer and Xavier de Planhol have pointed out, the high Pontic chain played a decisive role in determining the different course of history in the eastern coastal region.[10] The arrival of large numbers of Turkic pastoral peoples had guaranteed that the population in northeastern Anatolia would be relatively quickly Turkicized and Islamized. In contrast, the eastern littoral was far less accessible to the semi-nomadic, stock-keeping peoples of the interior highlands. The passes that cut through the mountains consisted of little more than narrow and twisting tracks, buried in deep snows during the winter. Descending into the valleys, these tracks traversed a landscape ideally suited for defensive purposes: virgin forests shrouded in mists at the upper elevations and a dense undergrowth of bushes and vines at the lower elevations.[11] By these circumstances, the rural societies of the coastal valleys were in a position to limit the numbers of pastoral newcomers who settled in their midst, just as the Greek Empire of Trebizond was in a position to resist military invasion and occupation by the Turco-Islamic states of the interior.

Viewed as a great mountain barrier, the Pontic chain explains why the rural societies of the eastern littoral were slow to change, as well as why the Greek Empire of Trebizond was to endure so long. Otherwise, topography and environment did not consistently function to isolate the coastal region from the outside world.[12] Even as the high mountains and dense vegetation defined an "island on the land," a kind of refuge area set apart from the interior highlands, its temperate climate and fertile soils were powerful magnets that lured peoples into it. The two opposed qualities of the landscape, defensibility balanced against desirability, led to a pattern of ethnic fragmentation. For whenever outsiders did succeed in penetrating the coastal region, they tended to retain elements of their distinctiveness.[13]

By the early medieval period, before the arrival of Turkic pastoral peoples in Anatolia, the northern slopes of the eastern Pontic Mountains were occupied by peoples who had colonized the region from different directions. Kartvelian-speakers from the Caucasus, eventually to be called the Lazi, had settled its eastern precincts. Greek-speakers from Sinop, eventually to be called Pontics, had settled the western precincts. Armenian-speakers from the interior highlands, eventually to be called Hemşin, had entered the eastern upper valleys above the Kartvelian-speakers and Greek-speakers.[14] Thus, the coastal region had inexorably drawn peoples from neighboring territories into its valleys, complicating the ethnic composition of the coastal region.

Almost surely, Turkic peoples appeared in most of the coastal valleys soon after their arrival in the interior highlands, perhaps as early as the eleventh century.[15] It is even likely that some of these early arrivals assimilated themselves to the existing inhabitants, losing their language and their religion, only to get them back centuries later.[16] Whatever the case, Turkic pastoral peoples did not initially enter and occupy the coastal region in large numbers, save where the mountains were lower and the landscape less vegetated. Çepni Turcomans, tribally organized pastoral peoples of heterodox Shi' background, first began to settle along the western littoral in the vicinity of Sinop, then reversed direction to move back toward the eastern littoral. By the thirteenth century, the emirates of these peoples governed the coastal region between Ordu and Sinop. And by the fourteenth century, Çepni Turcomans were moving still further eastward, settling the more accessible lower valleys just to the west of the town of Trabzon.[17]

At the moment of Ottoman incorporation, the overall distribution of ethnic groups in the early province of Trabzon can be roughly described as follows.[18] Greek-speakers inhabited most of the lower and upper coastal valleys near Trabzon, both to the east and to the west. This inner core of Greek-speakers was flanked by Kartvelian-speakers living in the valleys east of Rize and by Turkic-speakers living in the valleys west of Giresun. Groups of Armenian-speakers inhabited some of the upper valleys above the Kartvelian-speakers in the east.[19] Groups of Greek-speakers inhabited some of the western upper valleys above the Turkic-speakers in the west.[20] This pattern of settlement then became further complicated during the period of Ottoman rule. From the later sixteenth century through the seventeenth century, large numbers of Muslim settlers, most of who were Turkish-speaking, but not necessarily Çepni Turcomans, moved into various parts of the eastern coastal region. Their arrival appears to have led to relocations and conversions among some portion of the Christian population, thereby enhancing the mixed and merged character of local communal groupings. Just as some number of Turkic pastoral peoples had probably become Orthodox during the earlier period, many of the older Byzantine peoples most certainly became Muslim during the later.[21]

Given the traces of many peoples and languages in the coastal region, travelers were consistently perplexed about the nature of its peoples, during the Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman periods, down to the present. By what name is the population to be called? What language do they speak? With what religion are they affiliated? These questions had no simple answers given the situation of ethnic fragmentation. Groups of different peoples were unevenly distributed across the landscape, sometimes interspersed among one another, and always mixing with one another. In one valley one language would be spoken, but in the neighboring valley another language might be spoken. Furthermore, in the same valley, one language might be spoken at the lower elevations and another at the higher elevations. At the same time, several languages would be spoken in the lowland and highland markets.

But even more puzzling to outsiders than the ethnic and linguistic complexity of the population was the fact that ethnicity and language were not correlated with political identity and religious affiliation during the later Ottoman period.[22] In the coastal region, as we shall see in later chapters, the older Byzantine peoples became Muslim by participating in an imperial project rather than by assimilating to a Turco-Islamic majority.

Society and State in the Pontic Enclave

The rural societies of the eastern coastal region have been adjudicated, taxed, and conscripted by a state system from the medieval period, during which time the town of Trabzon consistently served as the region's administrative, military, religious, and commercial center. As Bryer has noted, the structure of the state system has been remarkably constant over the centuries.[23] The valley-systems that constituted districts (bandon) in the ninth-century Byzantine province (thema) of Chaldia reappeared as districts in the Greek Empire of Trebizond. Later, they became districts in the sixteenth-century province (paşalıık) of Trabzon, and then reappeared once again as districts in the twentieth-century provinces (vilayet) of the Turkish Republic. This structure points to the strategic position of the regional capital and its links to other major markets and ports.

Walled and fortified from the medieval period, the town of Trabzon was situated on a rocky coastal promontory rising between two ravines. Some of the best anchorages along the eastern coast are in the vicinity, and a route from the town through the mountains is passable during both the summer and the winter. An entrepôt for maritime and overland commerce, the regional capital was inhabited by officials, mercenaries, merchants, craftsmen, travelers, and adventurers of diverse backgrounds from different homelands.[24] The rural societies flanking the regional capital were in contact with the more cosmopolitan society that appeared there, and some number of their residents lived and worked in its administrative, military, religious, and commercial centers. As we shall see, however, their links with the outside world beyond their valleys was not restricted to this single channel.

An early hint of the special relationship between rural societies and the state system appears in the works of Procopius. The sixth-century Byzantine historian refers to the inhabitants of the coastal region as the "Romans who are called Pontics." In so choosing his words, Procopius designated rural societies of the coastal valleys as a provincial population of the Byzantine Empire. He therefore conceived of a collection of different peoples speaking different languages as representatives of an imperial civilization. Much later, during the time of the Greek Empire of Trebizond, outsiders had considered the inhabitants of the coastal region to be primarily "Laz." Once again, the term in question characterized a diverse collection of peoples as the provincial population of what was then a "regional" imperial civilization.[25]

In the eighteenth century the same pattern appears again, even though the population in question was no longer either Byzantine or Christian. Outsiders commonly used the term "Laz" to describe what was now a large Muslim majority in the coastal region as a provincial population of another imperial civilization, that of the Ottoman Empire. As before, this provincial population included a diverse collection of peoples. Descendants of Turkic-speakers, Kartvelian-speakers, Greek-speakers, and Armenian-speakers had aligned themselves, however imperfectly, with official Ottoman Islam, and all of them spoke greater or lesser snatches of Ottoman Turkish. Since none of the four groups had previously featured these attributes (Turkic pastoral peoples included), they each separately indicate a strong tendency for the residents of the coastal valleys to position themselves in the larger social, economic, and political world beyond their scattered hamlets.[26]

While geography worked to preserve ethnic fragments and linguistic archaisms, it also worked to homogenize identities and relationships. The terrain of the eastern coastal region isolated the residents of the coastal valleys from local processes of social assimilation, but it also encouraged, if not necessitated, that they connect themselves with the outside world. Each valley linked oversea routes with overland trade routes. Some had good anchorages along their shorelines. Some provided easy access to the interior highlands through mountain passes. Some were located near major markets of Anatolia. Some combined all these features, so that they rivaled the regional capital at Trabzon. At the same time, each valley was also a total ecological system. Every year individuals, families, and communities moved up and down the valley. Petty traders, craftsmen, and wage laborers moved from the markets of the coastal lowlands to the markets of the interior highlands. Family members moved cattle and flocks in stages through the upper valleys, gradually ascending to the highland pastures in the spring and descending to their lowland hamlets in the fall. Entire villages moved between a winter settlement near the shoreline and a summer settlement in the mountains.

As homelands, the valleys were not what they first appeared to be, motley groups of people living in isolated hamlets dispersed across the landscape. The valleys were instead transit systems whose inhabitants had a large stake in the security of the people, animals, and goods moving through them. All the residents of each valley-system, whether lowlanders or highlanders, therefore had an interest in knowing one another and cooperating with one another. Accordingly, each valley-system comprised an integrated social network. That is to say, all its residents were more or less organized for the purpose of communicating information, organizing cooperative ventures, and providing mutual assistance. In this respect, the peoples of the coastal region, densely settled and agriculturally impoverished, were also oriented toward outside markets of all kinds, for labor, skills, services, and goods. And given the existence of networks of relationships and lines of communication inside their homelands, they were in a position to make their way in the world abroad beyond their coastal valleys.

As a consequence, the rural areas of the coastal valleys have been inhabited for many, many centuries by cash-croppers, soldiers, miners, carpenters, sailors, metal-workers, weavers, rope-makers, dyers, masons, cooks, laborers, and traders, as well as a small minority of extortionists, counterfeiters, smugglers, gunrunners, kidnappers, bandits, pirates, and assassins. The residents of the rural areas have plied all these legitimate and illegitimate activities in their homelands since ancient times, but they have also left their homelands to go abroad as migrants when there was an opportunity to do so. Similarly, just as these rural societies have been oriented to external market conditions, so, too, outsiders were always in a position to become insiders among them. Certain kinds of "specialists" have always infiltrated the coastal region when they had something to offer its resident peoples.[27] Among them we find animal transporters, religious teachers, military officers, stone-layers, wood-carvers, metalworkers, shipwrights, and so on. In this respect, the coastal region, which is otherwise completely rural in character, bears a resemblance to an urban center.

There were, then, two contradictory sides to the rural societies of this segment of the coastal region. Their homelands served as isolated refuges where archaic traits and dialects were preserved. And yet, their homelands, while isolated refuges, were also connected with the outside world. Topography and environment did not have a single, undivided consequence for social life in the coastal region. It worked to fragment human groups at the level of mother tongue and family life even as it also worked to unify human groups at a level of entrepreneurial, governmental, and educational engagements.

The two opposed tendencies explain why the residents of the coastal region have more or less consistently had the reputation of hicks since the medieval period. They issued from their remote valleys with outlandish accents, manners, and dress, but, unlike other rural peoples, they were nonetheless consistently present and active in provincial centers. What is significant is not that they were dismissed as rustics, but rather that they were always on the scene in the towns and cities of Asia Minor, ready and available to be designated as countrified interlopers. The peoples of the coastal region were always striving to integrate themselves into a larger state society, even as they could rarely achieve urbanity and sophistication, since most of them retained contact with their rural homelands as refuges and hideouts.[28]

Once any group of people left the interior highlands, crossed the Pontic Mountains, and settled in the coastal region, their work habits and mental outlooks were inexorably transformed. Gradually, the newcomers found it more and more difficult to conceive of the local community as an entity in itself and they came to see themselves in relation to the commercial and governmental systems beyond their valley homelands. They tended, then, both as individuals and communities, to see themselves as participants in universal projects of power and truth. Once in the coastal region, the heterodox became orthodox and the illiterate became literate. They became partisans first of Romanism and Byzantinism, then of Ottomanism and Nationalism. A further comparison of the coastal region with the interior highlands brings to light the way in which local and global factors combined to reinforce a preoccupation with, as I have chosen to phrase it, "the horizon of elsewheres."

Economic Flexibility and Elasticity

Across the Pontic chain in the interior highlands, subsistence farming and herding are demanding occupations, narrowly constrained by circumstances and resources. Winters are long, requiring the maintenance of sturdy houses, stables, and barns. In the absence of trees, fuel for cooking and heating is limited but necessary for any measure of comfort. Plough farming is not possible without large draft animals, which have to be maintained year-round. The growing season is short, so farm work intensifies at specific times, when family groups must work long and hard. During the warmer months, from March through November, there is a time to sow, a time to harvest, a time to gather and store fuel, a time to pasture and corral flocks, and a time to repair roofs and walls. Moreover, each household's activities cannot be organized independently from others. The fields of the villagers are mingled together at the periphery of their nucleated settlements. Fallowing, ploughing, harvesting, pasturing, manuring, and penning are virtually impossible without collective agreements and mutual assistance.

In contrast, the subsistence activities of family groups in the coastal region are not so closely defined by climate, labor power, resources, equipment, and community. In most places the growing season is long, almost year-round near the shoreline. Water is almost never in short supply, and wood for fuel is readily available. Each hamlet is more or less isolated in the midst of its own lands, and, in many places, it stands as a kind of little kingdom on a promontory or hilltop. As a result, the villagers, especially the majority in the lower valleys, are able to organize their subsistence activities more flexibly, coordinating them with other kinds of engagements and activities. The maize and bean gardens can always be made a little larger or a little smaller.[29] The planting of potatoes and squash can be expanded or contracted during the warmer months, just as the planting of cabbage and leeks can be expanded or contracted during the colder months. Since there is no need for oxen, ploughs, horses, and carts, subsistence activities can also be incrementally adjusted downto a bare minimum. There can always be a few more or a few less animals in the stable beneath the house, or even no animals at all.[30]

By virtue of the flexibility and elasticity of subsistence activities, those members of the household who preoccupy themselves with subsistence activities are variable in number. Some members of the household can be absent from the hamlet for long periods of time, even during the warmer months, without seriously interrupting the cycle of farming and herding activities. When other sources of income present themselves, some members of the households can leave. It is almost always men who do so. Those remaining, some of the men and all of the women, can scale back their subsistence activities accordingly. This allows for the coordination of subsistence farming and herding with itinerant trades and crafts. Such coordination was an ancient practice in the coastal region, and especially characteristic of the later centuries of the Ottoman Empire.

If a handicraft was seasonally in demand in a town of the interior highlands, some of the men of the coastal region learned it, temporarily migrated, and practiced it. If commercial possibilities arose in some section of Asia Minor, the Caucasus, eastern Europe, or the Middle East, some went there as petty traders and wage laborers.[31] If state officials were looking for soldiers and sailors, some took this chance to gain some experience abroad. As a consequence, the men of the coastal region were never entirely bound to the peasant way of life.[32] Their thinking and practice took into account opportunities that might appear over the horizon.[33] If they had a keen sense of their local origins, they nonetheless conceived themselves in relationship to all kinds of elsewheres, even to the point that subsistence became a secondary rather than primary concern.[34] Cash-cropping, handicrafts, manufactures, and labor migration therefore tended to degrade the production of basic food stuffs.[35]

The assortment of local products continually changed and shifted with market conditions.[36] During the later Ottoman period, dried and fresh fruits, such as grapes, cherries, and citrus, were cultivated and exported in significant quantities to Istanbul. To the east, locally grown hemp and flax were used to make thread, nets, and cloths.[37] A fine linen (Trabzon bezi, Rize bezi) that became prized in the Middle East and Europe was also produced.[38] To the west, grapes from vineyards were distilled into a powerful liqueur (nardenk) and exported to the Crimea for reduction into eau-de-vie.[39] Wooden boats (kayıık) for transporting cargo to Black Sea ports were constructed in Hopa, Rize, and Araklıı, as well as elsewhere along the coast in secluded coves invisible from the sea.[40] Copper, lead, and silver were mined, smelted, and cast in different vicinities near Trabzon.[41] Knives, swords, pistols, and rifles were manufactured no later than the nineteenth century and perhaps considerably earlier.[42] Paper money was counterfeited no later than the beginning of the nineteenth century, and one can guess that metal counterfeits had been produced from ancient times.[43] Most of the local products that flourished during later Ottoman period have declined or vanished since the beginning of the last century, only to be replaced with others. But a very few were produced for centuries, and some for much longer. Tea is a crop grown today that was first introduced between Rize and Trabzon during the mid-twentieth century, but hazelnuts have been cultivated and exported from the eastern littoral for two thousand years.[44]

By virtue of a market orientation, subsistence farming and herding placed no Malthusian limit on how many people could inhabit the eastern coastal region.[45] So the population of the coastal region, like that of a metropolitan area, could expand indefinitely, limited only by the ingenuity of its inhabitants to produce for a market, turn a profit in commerce, or go abroad to ply a trade or seek out work.[46] And in fact the population did expand once the coastal region became more firmly integrated into the imperial system. British consul James Brant, traveling eastward from Trabzon in 1835, made the following observation:

As the population doubled, redoubled, and doubled again, grain deficits became endemic to the eastern coastal region.[48] And when such deficits were exacerbated by poor harvests and market crises, the rural societies of the coastal region suffered extreme hardship and impoverishment.[49] British consul William Palgrave, who resided in Trabzon from 1868 to 1873, described the miserable condition of the villagers near Trabzon in the following terms:I passed in succession the districts of Yemourah, Surmenah, Oph, Rizah and Lazistan. . . . The country is so wooded and mountainous, that it does not produce grain sufficient for the consumption of the population, yet not a spot capable of cultivation appears to be left untilled. Corn fields are to be seen hanging on the precipitous sides of mountains, which no plough could arrive at. The ground is prepared by manual labour, a two pronged fork of a construction peculiar to the country being used for this purpose. Indian corn is the grain usually grown and it is seldom that any other is used for bread by the people. What the country does not supply is procured from Gouriel and Mingrelia.[47]

The inhabitants are, with hardly an exception, wretchedly poor. The plot of ground on which each man cultivates his maize, hemp, and garden stuff, yields little more than enough for his own personal uses and those of his family; the maize–field and garden supply their staple food, and the hemp their clothing: this last coarse and ragged beyond belief. And no wonder, where a single suit has to do duty alike for summer and winter, day and night.[50]

Cash-cropping and labor migration were alternatives to the meager fare gained from gardens and stables, but they also exacerbated the precariousness of rural life. The market orientation of the villagers decreased the local production of basic foodstuffs and so increased dependency on external economic and political conditions. The villagers were ever more inclined to contemplate the possibilities and opportunities beyond their homelands as the population density climbed. The eastern coastal region therefore represented an impressive reservoir of men who were able and eager to take up any opportunity that might be present itself. At a certain point of crisis in the imperial project, Ottoman officials took note of this fact.

Ottomanization of Trabzonlus, Trabzonization of the Ottomans

In addition to cash-cropping, handicrafts, manufactures, and labor migration, some inhabitants of the coastal valleys had always entered governmental service. Most commonly, it seems, they served as mercenaries for all kinds of power-holders in the coastal region as well as other parts of Asia Minor. As it happened, however, the inhabitants of the eastern coastal region began to expand the extent of their participation in centralized governmental institutions during the third century of Ottoman rule. Afterward, the rural societies might have appeared to the casual observer as dispersed and fragmented peasantries, but they had become, more than ever before, provincial extensions of the imperial system.

During the second half of the seventeenth century, official policies led to an unprecedented increase in the numbers of individuals associated with military and religious institutions in all the core provinces of the Ottoman Empire. In a context of internal instability and external competition, a significant fraction of the population joined the ranks of soldiers and preachers. Sometimes employed and sometimes unemployed, tens of thousands of individuals came to identify themselves with the imperial system. The rise in the numbers of soldiers and preachers, which would have had affected towns and villages everywhere, had a special impact on the rural societies of the coastal region, once again by reason of topography and environment.

Elsewhere among the peasant societies of Anatolia, soldiering and preaching had the potential to wreck the rural economy coming and going. By the coincidence of these activities with the growing season, they drew able-bodied men out of the subsistence economy when they were most needed, then returned them when prospects for productive activities were at a low point. In contrast, the men of the eastern coastal region could depart from and return to their homelands without seriously disrupting the subsistence economy. And given their background of participation in market and state systems, they could immediately understand how state service was an opportunity rather than a catastrophe. Soldiering and preaching were ways of insinuating themselves in the social networks of the state system. And as well, soldiering and preaching could be combined with trade and crafts.[51] As a consequence, the rural societies of the province of Trabzon did not remain Christian but became largely Muslim, as they were once again, but more than even, re–integrated within a state and market system, now global rather than regional.

Women's labor in the gardens and stables was the precondition for men's participation in the horizon of elsewheres. It was the men who soldiered and preached and, in doing so, traveled to other towns, resided in dormitories, socialized in coffeehouses, set up shops and ateliers in markets, ran caravans into eastern Anatolia, and sailed transport ships along the coast. If women remained involved in the market economy, that is to say, with cash-cropping, handicrafts, and manufactures, they did so only within their mountain fastnesses. And by the logic of such circumstances, women's work in the fields and stables became the confirmation that the men of the household were something more than peasants. Women were therefore obliged to work in the fields and stables whether or not the men were absent from the homestead.

In this way, local engagement in the imperial project came to shape gender relations in the coastal valleys of the eastern littoral. Women were closely identified with subsistence tasks, which were necessary but unrewarding and undignified. Men were identified with governmental and commercial engagements beyond the hamlet, which were potentially more rewarding and certainly more prestigious and dignified. By the pressure to claim social standing, each household was organized in such a way that the men were freed from subsistence activities, regardless of their actual position or achievement. While men were absent from the homestead during the day (in principle if not in fact), women took care of the children, the house, the stable, and the fields.[52] It was just as important for a man to be seen as free from farming chores as it was for him to be involved in some other rewarding enterprise.

The issue was as much a question of propriety as economic necessity or possibility. When they were able to do so, regardless of their actual occupation, men wore the "official" attire of businessmen, professionals, and bureaucrats. Women, regardless of their circumstances, wore the peasant costumes of striped aprons (önlük) and shawls (çarşaf) or blouses and baggy pants (şalvar), dress suitable for heaving, carrying, digging, and clearing. Wicker baskets, a distinctive feature of the subsistence economy in the coastal region, were another indication of the differing relationship of men and women to subsistence activities.

Women with baskets—some as small as a rucksack and some as large as a person—took the place of animal power and wheeled vehicles.[53] Until recently, women were seldom seen away from their homesteads without one, gathering fodder for the stables, harvesting crops from the fields, or transporting produce and supplies. Women were the means by which men could become something other than subsistence farmers and herders, that is to say, the means by which men could claim imperial identities and affiliations. This explains why there was competition among men for the control of women as well as why this competition was expressed during marriage festivities in terms of the assembly of large numbers of men engaging in impressive displays of firearms. One could not be a participant in the sovereign power of the state system without women's labor, hence the manifestations of numbers and firearms were necessarily linked with claims over women. Villagers who saw themselves as potential participants in the sovereign power of the state system were also villagers for whom numbers and firearms symbolized their claim to women.

In the same way, imperial engagement explains why the eastern Black Sea people are known by story and proverb as possessive and jealous. Competition for women's labor arose because men were required to be absent from the homestead, not just during the day, but also during major parts of the year. Locally, these circumstances were associated with the notion that women should be able to defend themselves with weapons in the absence of men.[54] But more tellingly, they reinforced the moralization of men's claims over women, such that a principle of manhood required respect for another man's claims over women. This moralization appears in the orientation of religious thinking and practice in the eastern coastal region. All those elements of official Islam that touch on the morality of gender relations are emphasized, if not exaggerated, in the eastern coastal region.

So it is that the eastern coastal region, by participation in imperial military and religious institutions, became famous for a "traditional" assertion of male rights over women. Andsince its soldiers and preachers became instrumental in the ottomanization of provincial society, so too they transmitted the moralization of gender relations to other parts of Anatolia. The male residents of the eastern Black Sea coast became soldiers and preachers only by the advantage of local circumstances. And as they did so, they carried into the state society their own special concerns that had arisen from the circumstances of their participation. As they were transformed by taking their place in the lower echelons of the imperial system, so too they transformed the lower echelons of the imperial system. Ottomanization of Trabzonlus led inexorably to Trabzonization of the Ottomans.

A State Society Before Contemporary Modernity

Travelers and visitors have repeatedly perceived the landscape of the eastern littoral as a stabilizing foundation for social life. Xenophon in the fifth century B.C.E., Procopius in the fifth century C.E., and then French consul Fontanier in 1827 all describe the same scene of isolated hamlets scattered across the hillsides. Topography and environment, it would seem, have always regenerated the same way of life, despite the arrival and departure of various peoples. A closer look reveals, however, that this continuity of observation is misleading.

Domestic architecture is less uniform here than anywhere else in Asia Minor. Sümerkan notes that the techniques of house construction in the coastal region change every fifteen to twenty kilometers, an indication of the diverse origins and skills of its inhabitants.[55] And if some domestic implements and structures are common to all the peoples of the littoral, reappearing in every coastal valley, such devices are everywhere named by different terms from different languages. Sümerkan notes, for example, that the maize granary was designated by as many as fifteen different terms.[56] And yet all this variability at the level of everyday practical activities is strangely accompanied by uniformity at the higher level of social relations. Sümerkan notes that the terms for domestic architecture are Arabic for activity rooms, Ottoman for the sitting room, and Persian for the balcony.[57] In other words, local fragmentation and difference is accompanied as well by the disruptions and intrusions of world commerce and imperial government.

The truth of the matter is that topography and environment worked to destabilize, not stabilize, the character of social life. On the one hand, outsiders were always attracted to this fertile and temperate region, thereby disrupting the consolidation of parochial habits and custom. On the other hand, once these outsiders had become insiders, they were pressed to orient themselves to the commercial and governmental systems beyond their homelands. And as the villagers oriented themselves to the market and state systems of which they were a part, so local identities and relationships never came into balance but always remained off-center, like the world system of which they were a part. The surface appearance of an unchang-ing way of life, dispersed homesteads in a garden landscape, therefore concealed a history of ethnic fragmentation and imperial reorientation.

The most perceptive observers of the old province of Trabzon noticed this peculiarity of the eastern coastal region, even though they did not understand exactly why or how it had come about.[58] J. Decourdemanche, who visited the coastal region during the 1850s, described the Muslim population as a collection of diverse peoples who had coalesced to form a regional society in the imperial system. "The inhabitants of Trabzon consist of many races . . . who came closer to each other in religion and speech [in the past so that] today they are one caste which has social and political influence.[59] Alfred Biliotti, serving as the British consul in 1873, also described the Muslim population as diverse in background but nonetheless united in their imperial sentiments and participation. "However much the Muslims who live here may be from the point of view of root or structure from different races, it can be thought that they are in the same fashion close to one another in regard to the Ottoman Empire, religious belief, and political ties.[60] When these observations were made, the steamship and telegraph had only recently arrived in this part of Asia Minor. It would be almost a century more before motor transport and electronic communications would become important factors in the social life of the coastal region. Nonetheless, in the absence of technological modernity, a collection of peoples living in a rural landscape more or less without towns had become a state-oriented society.

Today, in the eastern Black Sea provinces of Turkey, from Artvin to Ordu, the traces of ethnicity, Lazi, Armenian, Greek, and Turkic, are easy to discover in language, stories, customs, and dress. And yet, in contrast to all these differences, the inhabitants of the rural societies still lack a strong interest in their parochial backgrounds and traditions.[61] With the exception of a few recent authors and books, there is no developed culture of ethnicity in the eastern coastal region.[62] Instead, social manners and relations are more or less homogeneous at a certain level, a direct reflection of a local engagement in wider market and state systems, now national as once before imperial.

These conditions of social life among eastern Black Sea peoples are indirectly recognized in Anatolian folklore. The diet of cornbread and yogurt is the simple and modest fare of village life in the coastal valleys. According to villagers and townsmen in the rest of Anatolia, these food items are said to be the cause of the restless energy and quick temper for which the "Laz" are famous. Cornbread and yogurt are indeed responsible for their liveliness, but only indirectly by their correlation with cash-cropping and labor migration. To be obliged to survive on cornbread and yogurt was also to have an intense interest in the horizon of elsewheres.

Notes

1. See Bryer and Winfield (1985, 1–16) for a more detailed description of the topography and ecology of the Pontic region.

2. Issawi (1980, 199–200) lists the distribution of crops in the province of Trabzon in1863 by percent of total quantity of agricultural production: wheat 6; barley 3; maize 52; oats 3; tobacco 10; vines 1; other 25 (beans 10, nuts 5, vegetables 4, potatoes 2, olives 2, mulberry 1, hemp 1).

3. This paragraph is written in the present tense. It describes patterns that were still widespread when I first visited the coastal region in the 1960s. These patterns have since become less prevalent because of the growth in the cash economy and increasing migration to the larger cities.

4. An anonymous reader for the University of California Press has reminded me that women commonly tend the fields in many parts of Anatolia. My analysis is a comparative one. Because of the character of agriculture in the coastal region, the practice of labor migration by the male population is arguably older and more general than elsewhere in Anatolia.

5. I have taken the phrase from the title of the book by Carey McWilliams (1973), who applied it to southern California, another coastal enclave of a most different kind.

6. This paragraph, like the preceding, is also written in the present tense, even though some of the patterns, such as the use of dung for fuel, are less prevalent than when I first visited the region in the 1960s.

7. Cahen 1968, 145–55, and Vryonis 1971, chap. 3.

8. By such a sequence, a process of social assimilation with the Turkic majority would appear to have been the precondition of conversion to Islam (Bryer 1975).

9. Bryer 1975, 116-17.

10. Planhol (1963a, 1963b, 1966a, 1966b) was the first to point out the role of topography and environment in retarding Turkish settlement. Bryer (1975, 118 n. 11) restates and revises Planhol's conclusions.

11. Cf. Bryer 1970, 33-34.

12. Cf. Bryer 1975, 116–17, who writes of "a historic Pontic separatism." I do not mean to refute this observation entirely, but rather to expose a contrary dimension of topography and environment in the coastal region.

13. Planhol (1966b, 1972) implicitly recognizes this feature of the coastal region in his later articles on comparative geography. See his account of the Pontic, the Elburz, and the Lebanon mountains as "shelter mountains." Planhol attributes the high population of each of these coastal regions to flight from the nomadic invasions occurring in the interior. I would argue that outsiders were consistently attracted to these temperate and fertile regions over the long term.

14. See the sections on Laz and Hemşin in Andrews and Benninghaus (1989).

15. The presence of small numbers of Turkic peoples in all the coastal region during the twelfth century seems likely but is not well documented. Hasan Umur records a court case (1951, Case No. 1, dated 1575/983) involving Turcomans (Türkmen taifesi) who were transporting goods from the shoreline up the river valleys of the district of Of.

16. In the 1960s, it was common for Greek-speaking, Armenian-speaking, and Lazi-speaking Muslims in the eastern coastal region to claim their forefathers had been Turks. Although such claims were no doubt inspired by nationalist ideology, they cannot be discounted entirely on these grounds alone. For example, Bilgin (1990, 220–22) finds individuals with Turkish names who were paying the ispenç, a tax imposed on Christians, not Muslims. He argues that these were early Turcoman immigrants who had become Orthodox.

17. Bryer (1975, 127–29) places thirteenth-century Turkish emirates in the vicinity of the present-day towns of Çarşamba and Ünye. According to Bryer (1975, 132), the Çepnis had occupied the coastal region up to the Harşit River not far from the regional capital. According to Sümer (1992, 48–49), they had entered the areas of Eynesil-Kürtün, Dereli, and Giresun-Tirebolu.

18. According to Birken (1976, 151–53), who cites Evliya Çelebi, the sub-provinces (sancak) of the Ottoman province (paşalıık) of Trabzon would have been Batum, Gönye, Rize, Trabzon, Maçka, and Ordu. Gümüşhane, which lies across the Pontic Mountains, was not part of the old province of Trabzon until later and not a separate sub-province thereof until 1847. Canıık, the western coastal region from Ordu to Sinop, was not part of the old province of Trabzon until the later nineteenth century.

19. These Armenians are loosely termed "the Hemşin" by themselves and by outside observers. This name associates them with a specific upper valley complex where today there is a district and town of that same name in the contemporary province of Rize. See the entries for Hemşin in Andrews and Benninghaus (1989) and, especially, Benninghaus (1989a).

20. By indirect comparative evidence, it is probable that Greek-speakers had retreated to the upper valleys of the western coastal region with the arrival of the Çepni Turcomans along the shoreline. For example, Poutouridou (1997–98), citing Vakalopoulos, notes that the retreat of Greek populations to remote and mountainous regions was a common occurrence in the Balkans during the Ottoman period. Along these lines, Greek Orthodox villagers formed new settlements in the upper valleys of the district of Of (eastern Trabzon) during the century following Ottoman incorporation. See in this regard the analysis of the Ottoman registers in the district of Of in chap. 5. The matter is disputed. Planhol (1963a, 1963b, 1966b) believes that traces of Greek Orthodox villages in the upper valleys to the west of the Trabzon were of ancient provenance. Bryer (1970, 45–47; 1975, 118 n. 11) argues that they were of more recent origin, probably no older than the seventeenth century. I suggest they may be correlated with the arrival of the Çepnis along the western coast.

21. Lowry 1977.

22. As Bryer (1969, 193) has put it, "the ethnic origins of the eastern Pontic peoples (18 are listed in an unofficial census of 1911) are probably past disentangling."

23. The coastal valleys from Rize to Giresun were the core districts of this regional state system, the farther coastal valleys, from Hopa eastward and from Ordu westward, its fringe districts (Bryer 1969, 194–95; Bryer and Winfield 1985, 10, 178).

24. There were good anchorages not far to the east and west along a coastline that otherwise featured very few natural harbors (Bryer and Winfield 1985, 7). A mountain path, suitable for animal transport, cut through the Pontic Mountains at the Zigana Pass (2025 meters) to reach the interior highlands.

25. Bryer 1966, 1967, and Benninghaus 1989b.

26. The Turkic-speakers, for whom this might seem to be a natural tendency, are in fact especially revealing as an example. Many of them arrive as tribally organized Çepni Turcomans of heterodox Shi'i background, but they soon become Sunni Muslims who identify with and participate in the imperial system (Sümer 1992, 53).

27. Many of the individuals whom I encountered in Rize, Of, and Sürmene told stories of their forebears migrating into the coastal region from Anatolia, Syria, or Iraq. This was true even in the district of Of, which has the reputation of being among the more insular of the coastal districts.

28. This may explain why indigenous populations of the coastal region have vanished without a trace. The "native" populations who are associated with the coastal region in ancient times have disappeared entirely by the early medieval period. See, for example, Bryer (1966; 1967, 161, 167), especially his comments on the Tzan. So it would seem that the "native" populations were unable to preserve elements of their parochial backgrounds, despite the defensive advantages of their homelands. Since the "natives" were not part of a regional society represented by a state system, one might guess that they were therefore absorbed by more experienced, colonizing peoples (Lazis, Greeks, Armenians, and Turks).

29. Maize had replaced millet as the staple crop in the province of Trabzon from the early seventeenth century. See Humlum (1942, 90) for the beginning of maize agriculture along the Black Sea coast. The adoption of maize would have presumably led to an increase in agricultural productivity. This increase may have consolidated the elasticity and flexibility of the subsistence economy, thereby leading to a stimulation of population growth through increasing labor migration.

30. During the 1960s, when labor migration to Germany was possible, some villages were virtually deserted of men during most of the year, save for those who were very young or old. Still, these villages continued to function as subsistence farms, perhaps no less productive than before.

31. In the last century, the Oflus were accustomed to migrating to Sevastapol, Sokhum, Anapa, and Batum for work. Some men told me they had heard their grandfathers speak of trips as traders to Rumania and the Crimea.

32. Some observers describe them as miserable farmers. Describing the Oflus, whom he visited briefly in 1872, Palgrave wrote, "Their best success is in pedlary and shop-keeping; their worst in agriculture; in handicraft, iron-work especially, they are tolerable; in masonry excellent" (PRO FO 526/8 p. 39, Jan. 29, 1873).

33. Hrand Andreasyan (Bijişkyan 1969, 61, n. 12) attributes to İ0nciciyan the remark that the people of Of were scattered in many different areas and that an important segment of them were blanket-makers in Istanbul. Dupré reported that two thousand "Lazes" embarked for Constantinople "to escape the vexations of their chiefs" (MAE CCCT L. 1, No. 73, June 1808). In Of, I heard the following saying: "The cripple of the Oflu went to America, / Where did his healthy son go to?" (Oflunun topalıı Amerikaya gitti. / Bunun sağlam oğlanıı nereye gitmiş?).

34. In 1966, I asked how it was that the villagers of the agriculturally impoverished upper valleys of Çaykara often seemed to be so prosperous. My interlocutor replied that they did not hesitate to leave their villages to seek work in Izmir, Istanbul, and Adana. They were not like the villagers of the interior highlands (Bayburt), who hated to leave their villages.

35. The idea of labor migration was explicitly associated with the doctrines of capitalism. In 1967, a shopkeeper in the district of Of explained, "If a man got any capital, he left Of. There was no way that capital could be used in Of itself. Those who stayed were those with little capital."

36. For an account of the economy of Trabzon at the beginning of the nineteenth century, see the report by consul Dupré (MAE CCCT L. 1, Nivôse An XII [Dec. 1803]). Also see Peysonnel (1787), who presents a report on the economy of the southern Black Sea during the mid-eighteenth century.

37. Peysonnel (1787, 69, 91) cites hemp as an important export at Rize and the principal export at Ünye. Palgrave (1887, 18) describes the hemp and maize grown on homestead gardens in Trabzon, adding that the hemp is used to make family clothes. He also lists 90 to 100 dyers in the town of Trabzon who used indigo to dye chenille imported from Izmir (Palgrave 1887, 75–76). Fontanier (1829, 8–9) describes an encounter with an indigo cloth-dyer at Sürmene.

38. Peysonnel (1787, 67–68) refers to four manufacturers of the cloths in the town of Rize and twelve more in the surrounding villages. The cloths were made in three different qualities and called "toile de trébizonde." They were the most important export of Rize and were shipped to Constantinople, Egypt, and North Africa. Dupré writes in 1803 that "All the industry in this town [Trabzon] consists of the manufacture of linen, the most of which is for making into shirts, of which use it is in great demand at Constantinople, and of a great deal of copper articles, essentially for domestic usage, of which the most part is exported" (MAE CCCT L. 1, Nivôse An XII [Dec. 1803]). The French consul reports in 1868 that the most important export from the village of Rize is a cloth called "toile de Rize," which is manufactured in three qualities. The highest quality is made of pure linen, the other two being mixed with cotton. The two inferior grades are also manufactured at Trabzon (MAE CCCT L. 8, No. 4, Aug. 1868). The French consul reports in 1901 that thread and cloth were exported from Trabzon to Bulgaria, Rumania, Turkey, and Egypt, and that textile manufactures and cotton filé were exported to England, Austria, and France (MAE CCCT L. 13, June 1901).

39. Dupré (MAE CCCT L. 1, Nivôse An XII [Dec. 1803]) and Peysonnel (1787, 69, 83) refer to this liqueur.

40. Large seafaring boats were still being constructed by hand at Kemer village between Sürmene and Of when I first visited the area in the 1960s. Later, in the 1970s, with help from a World Bank loan, the villagers were able to construct a sheltered anchorage and to build large motor-driven boats from steel plate. Peysonnel (1787, 71–72) appears to have had a report of shipbuilding at this site in the mid-eighteenth century, but first-hand European observers were apparently unaware of it some decades later.

41. Dupré (MAE CCCT L. 1, Nivôse An XII [Dec. 1803]). Cuinet (1890–95) counted twenty-one silver-bearing lead mines, thirty-four copper mines, three of copper and lead, two of manganese, ten of iron, and two of coal for the sub-province of Trabzon (Bryer and Winfield 1985, 3).

42. Bryer and Winfield 1985, 3. When I first visited Trabzon local foundry workers and machinists were able to turn out copies of Colt 45s and Smith & Wessons (locally pronounced as "jolt kurk besh" and "seemeeteevesson," respectively).

43. Bijişkyan (1969, 61) writes that the Oflus "are talented to the extent of being able to print counterfeit money." Smelting and casting are ancient activities. It would be surprising if they were not also applied to counterfeiting.

44. Bryer (1975, 122), correcting Planhol (1963a, 1963b, 1966b), documents the export of hazelnuts during the medieval period.

45. The population of the eastern coastal region rose sharply during most of the Ottoman period, no doubt for a variety of reasons. The reintegration of the coastal region with the interior highlands after Ottoman incorporation, and the arrival of New World crops were perhaps among the several causes.

46. Thus cash-cropping, handicrafts, and manufactures are not a local response to grain deficits so much as the cause of them. Bryer (1975, 122) notes that hazelnuts are a virtual monoculture in some districts. Palgrave observed that flax was the primary crop at Rize and that grain and maize were secondary (PRO FO 195/812 p. 487, Feb. 16, 1868).

47. Brant 1836, 192.

48. Bilgin (1990, 269) cites a document mentioning grain deficits during the early sixteenth century (before maize). Umur (1951, 67–68) cites an official document, dated 1615/1024, mentioning grain deficits in the villages of Of (also before maize). Peysonnel (1787 [1762], 66) documents grain deficits at Rize during the middle of the eighteenth century. Fontanier (1829, chap. 1) traveled by boat from Redut-Kaleh to Trabzon in 1827. The boat, captained by a Sürmeneli, had carried a cargo of citrus and dried fruit from Trabzon and was returning with a cargo of maize. For other references to grain deficits, see MAE CCCT L. 2, BPMT No. 12, Jan. 1813, in which the province is reported to be threatened with a grain deficit; and MAE CCCT L. 5, No. 25, July 1846, in which Trabzon and its surrounding villages are said to have a grain deficit.

49. In 1829, food production was disrupted by Osman Pasha Hazinedaroğlu's campaigns against the local elites in the coastal districts. In 1830 and 1831, the harvest was especially poor and food was very limited (Bryer 1969, 202–3; Bilgin 1990, 298). In 1880, Biliotti describes a bad harvest and severe winter that, aggravated by the aftereffects of the recent war with Russia, was responsible for usurious loans, severe inflation, banditry, and mutiny in Trabzon (PRO FO 195/1329, No. 25, July 9, 1880).

50. Palgrave 1887, 18.

51. When individuals from the coastal region joined military expeditions, they also continued their entrepreneurial activities. Buying and selling was always a part of a military campaign, and for some perhaps the most important part. Ferrières-Sauveboeuf (1790, 233) describes an Ottoman military campaign in eastern Europe. He writes, "The army never moves in order, and the Turks refuse to form columns, either to protect their marches against surprise or to enable their troops to move about more easily in enemy territory. Those [of the troops] who practice some kind of profession always move on ahead in order to prepare their shops, where they busy themselves as in the towns, so that the camps resemble more a fair for artisans than an army of soldiers."

52. These tasks could be performed without the assistance of men, but the result was often endless, grueling labor. During the 1960s, young women in the villages in their thirties frequently appeared to be in their fifties, and fathers attempted to marry their daughters to men whose prospects were promising so that the latter would not make their wives into drudges.

53. Meeker 1971.

54. In the 1960s, I was told that women were given rifles to defend themselves when left alone in their homesteads and were just as skilled as men in their use.

55. Sümerkan 1987, 21.

56. Ibid., 28.

57. Sümerkan (1987, 30), who is specifically referring to the region of Rize, Of, and Sürmene, also notes that the terminology of the stable is primarily Greek. By his observations, those areas of the house that were social in character came under the influence of imperial civilization more than those areas that were utilitarian in character.

58. W. G. Palgrave, who perceived the population in terms of racial classifications, was scandalized by the "mixtures" he encountered in the population of Trabzon (PRO FO 526/8, "On the Lazistan Coast . . . ," Jan. 1873).

59. Decourdemanche 1874, 361.

60. Consular report, Sept. 1873, cited by Şimşir (1982, vol. 2, 4). Also see PRO FO 195/1141, Jan. 1877, Biliotti.

61. The Lazi would be the most likely grouping to develop some form of ethnic identity since they are a large population that is territorially concentrated. However, see Benninghaus (1989b) for a discussion of the lack of a clearly defined ethnic identity among the Lazi. Also see his citation of Marr, who observed in 1920 that the Lazi did not have a strong ethnic identity or favor their language. Also see Hann and Beller-Hann (2001) for a recent evaluation of ethnic identity among the Lazi.

62. See, for example, Asan (1996) and Aksamaz (1997).

4. Empire

Gaze, Discipline, Rule

The Problem

In the last chapter, I noted that the inhabitants of the eastern coastal region eventually came to identify with and participate in the institutions of the Ottoman Empire. But if these rural peoples were inclined to align themselves with the imperial system, this does not mean that the ruling institution itself would have permitted, let alone encouraged, such an accommodation. Indeed, the very idea of a rural people becoming ottomanist in orientation contradicts the prevailing historiography of the Ottoman Empire. Most commentaries have emphasized an unbridgeable divide between its ruling (askeri) class of state officials and its ordinary subjects (reaya), both Muslim and Christian. How then could a population of gardeners residing in remote mountain hamlets find themselves a place in the imperial system?

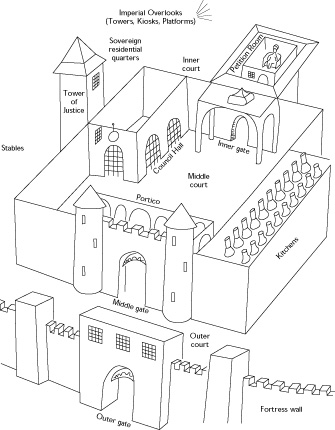

To answer this question, I first review how the Ottomans incorporated the eastern coastal region soon after the conquest of Constantinople, at a time when they were perfecting the classical ruling institution. This done, I analyze the architecture and ceremony of the governmental complexes that they built in the new imperial capital. This analysis features a double objective: to lay bare the distinctive configuration of sovereign power in the imperial system, and to expose channels of popular identification and participation that would lead into it.

Ottoman Centralism and Exclusivity

From the early sixteenth century, western European observers began to perceive the Ottoman Empire as a remarkable example of the centralism and exclusivity of sovereign power. What they noticed were the features of a new imperial system that Mehmet II had developed following his conquest of Constantinople in 1453.[1] Niccolò Machiavelli's comparison of the French and Ottoman governments in The Prince (1515) exemplifies the contemporary assessment:

The passage points to a stereotype of Ottoman government that had come to prevail in Christian Europe. The sultan ruled through a body of officials having the legal status of household slaves. Recruited from the children of Christian families and trained from adolescence within the confines of the sultan's palace, they had no independent social identities or loyalties.[3] At the same time, these slave officials (kul) were unchallenged by any system of estates. There was no aristocracy composed of lords who ruled their own peoples and territories, and no bourgeoisie composed of merchants or bankers who had been granted the privilege of governing their own towns and cities. The "Grand Turk," as the sultan was sometimes styled in Christian Europe, seemed to enjoy a measure of sovereign power unmatched by any other monarch in early modern Europe.The entire monarchy of the Turk is governed by one lord, the others are his servants; and, dividing his kingdom into sanjaks [sub-provinces], he sends there different administrators, and shifts and changes them as he chooses. But the King of France is placed in the midst of an ancient body of lords, acknowledged by their own subjects, and beloved by them; they have their own prerogatives, nor can the king take these away except at his peril. Therefore, he who considers both of these states will recognize great difficulties in seizing the state of the Turk, but, once it is conquered, great ease in holding it. The causes of the difficulties in seizing the kingdom of the Turk are that the usurper cannot be called in by the princes of the kingdom, nor can he hope to be assisted in his designs by the revolt of those whom the lord has around him. This arises from the reasons given above; for his ministers, being all slaves and bondmen, can only be corrupted with great difficulty, and one can expect little advantage from them when they have been corrupted, as they cannot carry the people with them, for the reasons assigned.[2]

Machiavelli's analysis reduced the ruling institution to a simple and static formula, thereby concealing both its complexity and instability. Still, his formula directs our attention to a distinctive feature of a new governmental system that gained ground during the early classical period. As the Ottomans launched a world imperial project during the later fifteenth century, they reinforced the centralism and exclusivity of the ruling institution. The recruitment and training of "slave" children to serve as high state officials was just one of the measures they adopted. By means of a range of policies, the Ottomans came to rely on a special class of military, administrative, and judicial officials who lacked affiliation with the governed. This raises the question of how the Ottomans incorporated a region whose peoples had such a large stake in market and state participation.

Mehmet II had annexed the Greek Empire of Trebizond (1461) just as he was beginning to devise and apply the new imperial system. Süleyman I had later reorganized the province (paşalıık) of Trabzon as a new administrative entity (1519) at the high point of classical institutions. So the substantial Christian population of the coastal region had become subjects just as the Ottomans were perfecting the centralism and exclusivity of the ruling institution. Higher state officials were more than ever composed of slave officials, and other entry points into the ranks of officialdom were regulated more than ever. Thus the shock of conquest was compounded by the shock of subjection. The old rural societies of the coastal region and the new imperial system were exactly mismatched. The inhabitants of the province of Trabzon had become part of a governmental system based on principles that stood in direct opposition to compelling local interests.

As we saw in the last chapter, the mismatch was transitory rather than permanent. As the domains of the ruling institution reached their maximum limits, the conduct of warfare was shifting away from the use of cavalry toward the use of infantry with firearms.[4] Under these circumstances, the Ottomans came to require larger numbers of men with a wider range of skills, even before the close of the classical period. They therefore took steps to widen the circle of participation in imperial military and religious institutions during the seventeenth century, in effect compromising the principles of centralism and exclusivity. As they did so, problems of imperial competition at the military frontier were joined by problems of internal instability in the core Ottoman provinces. Provincial governors had begun to defy the central government, asserting themselves by collecting illegal taxes and maintaining their own private armies. In response, the palace widened the privileges and prerogatives of provincial elites at the district level in hopes of curbing the powers of provincial governors.[5] As a result, principles of centralism and exclusivity were compromised still further. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, the distribution of sovereign power had moved outward and downward into the imperial system, weakening both central and provincial government. Higher state officials found themselves unable to rule save with the acquiescence and assistance of provincial elites.[6] The post-classical period was thereby characterized by a progressive decentralization of sovereign power.

All the core Ottoman provinces were affected by the changes I have just summarized, but the province of Trabzon is an especially revealing example of the phases of decentralization. By the close of the seventeenth century, many of the districts where the population had been almost entirely Christian at the moment of Ottoman incorporation had become almost entirely Muslim. Furthermore, large numbers of the men among these new Muslim populations had associated themselves with local branches of imperial military and religious institutions. By the close of the eighteenth century, local participation in imperial military and religious institutions had resulted in an entirely new relationship of state and society. Provincial elites at the head of armed followings asserted their prerogatives in the imperial system, sometimes defying, even threatening, higher state officials, both those in Trabzon as well as in Istanbul.

The instance of the eastern coastal region therefore poses questions of general significance for the understanding of the ottomanization of provincial society in other parts of Asia Minor and the Balkans. How did a population composed of different ethnic groups attached to different religions come to participate in imperial military and religious institutions? And in doing so, how did this diverse and mixed population become state-oriented, official Muslims, given that the imperial regime was based on radical principles of centralism and exclusivity?

Ottoman Incorporation of Trabzon

In his account of the ruling institution during the classical period, İİnalcıık explains how the palace, the seat of centralized government, organized and supervised the core Ottoman provinces in Asia Minor and the Balkans.[7] A hierarchy of military officers was appointed to govern a hierarchy of administrative units. There was a governor of each province (beylerbeyi), a few sub-governors of its several sub-provinces (sancakbeyi), and a large number of subordinate officers (sipahi) assigned to groups of villages (tıımar) in the sub-districts of each sub-province.[8] The palace appointed the governors to their positions for a limited term, rotating them from province to province. The palace also approved the governor's appointments of subordinate officers, also for a limited term, rotating their assignments from time to time.[9] The powers of this hierarchy of military officers was further subject to certain checks and balances. The chief treasury official (hazine kethüdasıı) was responsible for seeing that the fiscal affairs of the province were in order. The chief court official (kadıı) issued judgments in accordance with administrative and religious law. The provincial governor could dismiss both these officials, but only upon notification of the palace.

As we have seen, the military, treasury, and judicial officials were members of a special class without ties to the lands and peoples they governed. Only some members of this special class would actually have been trained in the institutions of the imperial capital, but of those who were not from Istanbul, only some would have been born and raised in the eastern coastal region. So the military, treasury, and judicial officials of the province of Trabzon had no multistranded ties with either the lands or the peoples for whom they were responsible. In this regard, they were unlike the lords and vassals of western Europe during the Middle Ages. They generally lacked castles or estates in the provinces to which they were posted, just as they lacked supporters among their inhabitants.

Furthermore, official procedures insured that the military governors would remain loyal and obedient servants of the central government rather than set down roots and build a following among the populations they governed. The sipahi, who were assigned to the countryside as a kind of country police force, best exemplify how this was accomplished. They came into direct contact with villagers on a routine basis in the course of collecting taxes, apprehending fugitives, imposing forced labor, and carrying out court decisions. They were therefore in a good position to build a base of local support, by favoring or disfavoring the villagers for whom they were responsible. But to counter this very possibility, the sipahi were subject to all kinds of controls.

The provincial governor could renew or revoke their appointment to a tıımar, as well as allow or disallow their relatives to succeed them as asipahi. So both their assignment in the countryside and their tenure as subordinate military officers were entirely dependent on higher state officials rather than local preference or election. Normally, they were rotated from district to district during the course of their service, so that they usually found themselves among peoples with whom they had no previous social contacts. They also had limited opportunity to develop social contacts since they were obliged to report for military campaigns, during which they were replaced by deputies for extended periods.[10] Treasury and judicial officials also subjected them to periodic inspections and were in a position to bring charges against them for malfeasance. Complaints could be lodged against them by townsmen and villagers and could result in dismissal if confirmed.[11]

In other words, all kinds of precautions had been adopted to prevent lower state officials from doing exactly what some would do during the period of decentralization. Policies of appointment, rotation, and inspection prevented the sipahi from setting down family lines and building local followings. It was as though the Ottomans had designed the institutions of the classical period in anticipation of the post-classical period that followed it. As we shall see, this would not have been a coincidence. Those who were responsible for inventing and implementing the imperial project would have taken care to neutralize a decentralizing potential that was inherent within its logic.

Four Ottoman registers attest to the thoroughness and efficiency with which the classical system of provincial government was put into practice in the province of Trabzon. Taken once every generation during the first century of incorporation, the registers tabulate the different classes of tıımar assignments, list the names of the sipahi appointed to them, and establish the tax obligations of each household head.[12] Although the same structure of government would have been operating in other parts of Asia Minor and the Balkans, the province of Trabzon was in certain respects unusual. Initially, as confirmed by the registers, the Ottomans appointed sipahi who had taken part in the conquest. Some of these individuals came from the western coastal region (the province of Canıık), which had been Islamized and Turkicized for many years.[13] More than a few came from still further away, from other parts of Asia Minor, or even the Balkans.[14] Thus, thesipahi in most of the coastal valleys of Trabzon would have been even more distant from their charges than was the case in some other provinces. The villagers among whom they resided were a newly subjected Byzantine population composed mostly of Orthodox Christians. The sipahi and the villagers therefore observed different customs, spoke different languages, and belonged to different religions.[15]