Chapter 2

Living with Regulation

Only someone deaf and blind could walk along St. Petersburg streets without knowing of the existence of [prostitution].

Russian Society for the Protection of Women (1910)

The system of nadzor created an institutional structure designed to encompass Russian prostitution. Yet the lives of women who engaged in prostitution were much more complex and variegated than the MVD rules allowed. Girls younger than the minimum age of 16 worked the streets, unlicensed brothels were run by unsupervised brothelkeepers, and most women who earned money as prostitutes had no desire to give up their passport in exchange for a yellow ticket. Nadzor, however, with its police inspectors and physicians, divided women into those who traded sex for money and those who did not. Whether or not women registered with the police as prostitutes, they were still living with regulation.

In this chapter, we shall examine the way prostitutes responded to that salient fact of their lives. The regulatory lists did not include most prostitutes, but regulation affected them nonetheless. Inside the system, a woman was subject to medical examinations and restrictions of her movements, and she had to earn money exclusively from prostitution. Outside the system, as a "clandestine" (tainaia ) prostitute a woman had much more flexibility, but she was also in constant danger of discovery. The goal of the medical police was to bring all prostitutes in—the desire of most women who made money from prostitution was to stay out.

Children and Prostitution

Work all day? What for, when someone like me can wear a hat and beautiful dress, and have white hands just like a lady?

Child prostitute in Kiev

Too young to register, child prostitutes could easily be found amid the ranks of Russia's clandestines. Urban neighborhoods such as Dumskaia Square in Kiev and Znamenskaia Square in St. Petersburg had reputations as centers of child prostitution.[1] Entire hotels reportedly catered to pedophiles, with prepubescent girls openly soliciting customers and sometimes supplying their parents with the money they earned from prostitution. Whereas child prostitution had once attracted only a limited clientele, Boris Bentovin, a physician who worked at Kalinkin Hospital, claimed that after the turn of the century the trade in children had soared and was no longer considered perverse or unusual.[2]

The onset of World War I apparently drove many more children to the streets. Social dislocation caused by war meant an increase in homelessness and a concomitant rise in children who were growing up in doorways and sleeping in boxes and on cemetery grounds. To support themselves, they engaged in prostitution. An official from the Kiev juvenile court attributed the child prostitution he encountered during the war years to "poverty and defenselessness," rather than simple hunger. Only two of the hundreds of young prostitutes he encountered between 1914 and 1917 traded in sex because they were on the verge of starvation.[3]

There are too many accounts of child prostitution in the sources to attribute its descriptions to adult paranoia and fantasy alone. The charitable organization known as the Russian Society for the Protection of Women (Rossiiskoe obshchestvo zashchity zhenshchin, hereafter ROZZh), for example, wrote in its annual report of a nine-year-old prostitute who reportedly lost her virginity to an "urchin" at the age of

[1] M. K. Mukalov, Deti ulitsy (St. Petersburg, 1906), pp. 8, 18 (quotation from child prostitute); Lincoln, In War's Dark Shadow, pp. 3–4, 124–26.

[2] Boris Bentovin, Deti-prostitutki (St. Petersburg, 1910), p. 4. See also Russkii vrach, no.18 (1909): 631. Laura Engelstein argues, "By 1910, . . . so-called child prostitutes came to symbolize the entire social problem in its most acute and menacing form." Engelstein, The Keys to Happiness: Sex and the Search for Modernity in Fin-de-Siècle Russia (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992), p. 284.

[3] Valerii Levitskii, "Deti-prostitutki v dni voiny," Vestnik vospitaniia, no. 2 (February 1917): 168–71. See also A. I. Zak, "Tipy detskoi besprizornosti, prestupnosti, i prostitutsii," Vestnik vospitaniia, no. 7 (October 1914): 70–101; no.8 (November 1914): 81–110.

seven and was then repeatedly molested by her father. When a policeman brought her to the local halfway house for prostitutes, she was smoking and apparently drunk. In response to a question about why she smoked and drank, she said, "It pleases men."[4] In 1913, a Petersburg feminist journal described how a male ROZZh member followed a soldier and two 11-year-old girls. When he caught up with this trio, he found one girl standing guard and another alone with the soldier. The soldier went free, but the girls were whisked off for examinations at a medical-police committee clinic.[5]

A colonel stationed near the Persian border at the turn of the century reported how his riflemen sought "diversions," which sometimes meant buying sex from the native women. He saw "one of these beauties" sleeping curled up on a fox coat. When the girl's mother kicked her awake, the colonel realized that she was a "real girl-child" (devochkasushchii rebenok ). In answer to his queries about her age, "with pride" the mother replied, "Twelve, but she has been acquainted with men since she was nine." Thus inspired, the colonel proposed that civilian authorities in the nearby city of Samarkand might ease the troops' burdens by bringing half a dozen such young women to live near the soldiers in remote outposts. To strengthen his case, he pointed out that the British had been doing something similar for their troops in India for years.[6]

On one hand, observers were outraged and disgusted by the idea of young girls catering to the sexual fancies of adult men. At the same time though, privileged society found something exciting and prurient about child prostitution. Surely Boris Bentovin gave his 1910 book on juvenile prostitution a distinctly erotic flavor when he described a 12-year-old girl—a "little female onanist" (devochka-onanistka )—who masturbated by leaning against sewing machines. He wrote about how, in order to satisfy the huge demand for virgins, some St. Petersburg midwives specialized in sewing on "hymens" fashioned from scraps of cow bladder or very thin pieces of rubber. A capsule of blood or a red-colored liquid would be attached, ready to provide a client with "the illusion of a 'first night.'" Bentovin's vision of St. Petersburg included girls as young as 10

[4] Rossiiskoe obshchestvo zashchity zhenshchin v 1909 g . (St. Petersburg, 1910), p. 70.

[5] "K voprosu o detskoi prostitutsii," Zhenskii vestnik, no. 9 (1913): 195.

[6] Polkovnik Lossovskii, "Kavkazskie strelki za Kaspiem," Razvedchik, no. 521 (October 10, 1900): 914. Indignant comments on his proposal can be found in Vrach, no. 42 (1900): 1295. For a report on a 14-year-old prostitute in Moscow, see "Maloletnaia prostitutka," Stolichnoe utro, no. 47 (July 24, 1907): 4.

or 11 who would "look you in the eye, promise you astonishing pleasures, and spew nasty language."[7]

Child prostitution existed for two reasons: first, there was a market for young bodies and, second, children of the urban poor faced the choice of earning negligible "honest" wages or making good money on the streets. The latter must have been a great temptation.[8] In 1909, a Petersburg newspaper wrote of two girls aged 9 and 11 who had been taken in by the House of Mercy, the private charitable institution dedicated to "reforming" prostitutes. On the street, these children earned 60 and 90 rubles a month respectively, that is, more than four and six times what an adult female worker might average.[9] When Bentovin asked a girl around 11 or 12 years old whether she was bothered by the "vileness and immorality" of her life, she reportedly answered, "Not in the least. . . . There's nothing so bad here. . . . It's much better than a brothel. . . . I get sweet and delicious things. . . . The little uncles [diad'ki ] are all really funny and kind. . . . If they come up with something bad, I don't do it."[10] Christine Stansell has shown that girls in the urban lower classes of nineteenth-century New York City faced sexual aggression from men at many turns; the "innocence" of childhood was in essence a bourgeois myth. Realistically, then, child prostitution could be viewed as a "way of turning a unilateral relationship into a reciprocal one."[11]

Medical-police committees struggled against juvenile prostitution by various means, but at least in St. Petersburg, police raids remained the weapon of choice. In 1889, the Petersburg committee picked up twenty-two girls between the ages of 11 and 15 for soliciting. According to Aleksandr Fedorov, they were from poor, morally corrupt families who would dispatch their daughters straight to the streets. The committee sent ten of the girls to the House of Mercy for correction and rehabilitation, but the remaining twelve, much to Fedorov's regret, were returned to their parents' care. In 1890, when seventeen minors were arrested, all wound up back with their families because the House of Mercy was

[7] Bentovin, Deti-prostitutki, pp. 4, 10–12, 33–34.

[8] On children living on Russia's urban streets, see Joan Neuberger, Hoolganism: Crime, Culture, and Power in St. Petersburg, 1900–1914 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1993), pp. 158–215.

[9] "Bor'ba s prostitutsiei," Rech ', no. 111 (April 25, 1909): 4.

[10] Bentovin, Deti-prostitutki, p. 15.

[11] Christine Stansell, City of Women: Sex and Class in New York, 1789–1860 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1986), p. 185.

full.[12] Minors, naturally, presented a dilemma to authorities. A physician from the Stavropol' provincial administration pinpointed part of the problem in a letter to the MVD branch that handled regulation after 1904, the Office of the Chief Medical Inspector (Upravlenie glavnago vrachebnago inspektora, hereafter UGVI): ministry rules directed the medical police to send underage girls and women to their parents or to the proper philanthropic institutions, but Stavropol' (like most Russian cities) had no such agencies and many children were orphaned.[13]

But the central issue was registration. State policies for this category of young women reflected some of the lingering ambivalence toward nadzor. As the author of a 1914 study of European prostitution put it, it was "the very acme of unwisdom and inhumanity" to brand 11-, 12-, and 13-year-old girls with the label of "prostitute."[14] Though the MVD considered itself in the business of controlling venereal disease by controlling prostitutes, it retreated from the aggressive surveillance of juveniles. In 1903, the ministry raised the minimum age of registration from 16 to 18, essentially lumping 16- and 17-year-old young women into the same category as children and giving them the automatic status of clandestine prostitutes.[15] Medical-police committees were expected to act accordingly, but local regulators, as usual, often did as they pleased. In Petersburg, for example, the existence of an "army" of juvenile prostitutes spurred authorities to lower the age of registration in 1909.[16] Among 379 prostitutes who were registered in the northern capital in 1914, 40 were under the age of 18, and 9 were 14 or 15 years old.[17]

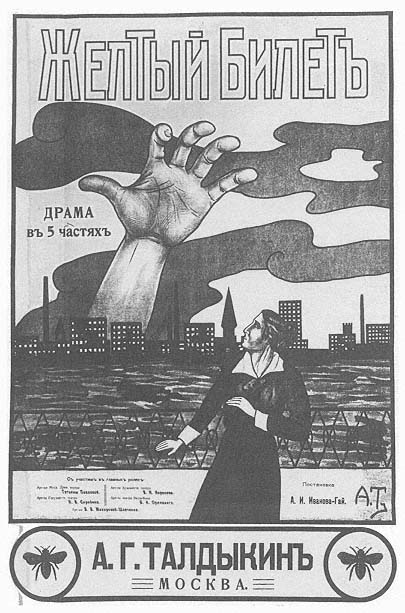

Authorities were understandably loath to condone and, in effect, institutionalize the sexual trade in children by issuing them yellow tickets, Yet the failure to subject young prostitutes to identification, inspection, and incarceration defeated regulation's very purpose, since children and young women with contagious diseases stood by definition outside medical-police surveillance. Petr Gratsianov recognized this dilemma when a European colleague at a Brussels conference proposed establish-

[12] Fedorov, Ocherk vrachebno-politseiskago nadzora, pp. 52, 54–55.

[13] TsGIA, UGVI, f. 1298, op. 1, d. 1730, letter of May 8, 1911.

[14] Flexner, Prostitution in Europe, pp. 152–53.

[15] A Tomsk physician blamed the revised age limit for the "almost boundless" spread of clandestine prostitution. V. M. Timofeev, "Otchet po nadzoru za prostitutsiei v gorode Tomske za 1911 god," Vrachebno-sanitarnaia khronika goroda Tomska, nos. 7–8 (July–August 1912): 369.

[16] Bentovin, Deti-prostitutki, p. 37.

[17] Otchet o deiatel'nosti Petrograndskago doma miloserdiia za 1914 g . (Petrograd, 1915), p. 18.

ing 21 as the minimum age for registration. To Gratsianov, age was irrelevant. "Regulation," he pointed out, "does not strive to punish the prostitute [who is suffering from a venereal disease], but only to render her harmless [obezvredit '] and completely isolate her."[18]

The reluctance of the state to move young women into a life ruled by the yellow ticket—despite the ostensible reasons for taking this step—shows how state authorities as well as women could be trapped in a tangled web of gender, morals, and ideology. From the vantage point of the regulationists, Gratsianov was right; logic demanded that all prostitutes fall under the state's purview. Nadzor, however, did not simply render the prostitute harmless and isolate her; it labeled her a "public woman," putting her movements and her body into public hands. The MVD bowed to this verity by raising the age limit and thereby undermining its own policies. Having refrained from putting girls into the social category of women who sold sex, the regulators tacitly acknowledged their system's injustice. They also bolstered the ranks of so-called "clandestine" prostitutes, the outlaw group that regulation paradoxically created.

"Clandestines"

It is impossible for those who do not wish to close their eyes before a gaping abyss not to ponder the question and extent of clandestine and open [iavnaia] prostitution in the big cities.

Dr. Vladimir Bekhterev (1910)

In 1900, when the number of registered prostitutes had reached approximately 34,000, The Women's Cause (Zhenskoe delo ) reported that anyone familiar with the problem of prostitution in Russia had to be aware that the actual number was close to ten times higher. Ten years later, the Social Democrat Aleksandra Kollontai asserted that the true numbers of prostitutes in St. Petersburg alone fell somewhere between 30,000 and 50,000. The psychiatrist Vladimir Bekhterev, who was president of the Psycho-Neurological Institute and the director of a clinic for mental and nervous diseases, quoted a figure of 50,000 prostitutes for Petersburg. According to his extravagant calculations, one in

[18] Gratsianov, "Briussel'skii mezhdunarodnyi s"ezd po priniatiiu mer bor'by s sifilisom i venericheskimi bolezniami," offprint from Russkii meditsinskii vestnik (St. Petersburg, 1899), pp. 3–33.

every nine women between the ages of 16 and 60 was earning money as a prostitute.[19]

In a description that made all of the capital sound like a veritable sex market, Robert Shikhman of the ROZZh claimed that St. Petersburg's restaurants, hotels, boutiques, and employment agencies served as centers of prostitution. Clandestine prostitutes lurked in taverns and tea shops, picking up customers and bringing them to nearby hotels. In some cases, bar and restaurant owners functioned as middlemen and supplied their clients with prostitutes. Some of these restaurants and shops paid no salaries to their female employees; women were expected to earn their money through prostitution.[20]

Although estimates of the numbers of clandestine prostitutes are impossible to verify, there is much evidence that prostitution flourished outside the official world of the medical police in Imperial Russia. During the year 1908, more than 11,000 women in Russia were arrested on suspicion of prostitution.[21] In 1909 members of a State Duma commission bowed to the existence of clandestine prostitution when they chose to define nonprostitutes as women "not earning a living through vice," rather than according to the more limited description, those "not inscribed in the ranks of public women." The number of registered women, they explained, was far from an accurate reflection of all those engaging in prostitution.[22]

Indeed, committee statistics could not begin to reflect the actual numbers of women who worked as prostitutes, either casually or professionally. Registration records showed that a significant number of women had worked as prostitutes before they actually registered. From 1908 to 1910, only between 34 and 39 percent of the women who newly registered with the St. Petersburg medical-police committee answered that they had been prostitutes for less than a year. At least 50 percent admitted they had been working as prostitutes for one to five years, and another 11 or 12 percent had been prostitutes for even longer.[23] In 1913, only two newly registered women (less than 0.5 percent) said they had

[19] Zhenskoe delo (June–July 1900): 201; Aleksandra M. Kollontai, "Zadachi s"ezda po bor'be s prostitutsiei," Vozrozhdenie, no. 5 (March 30, 1910): 8; Vladimir Bekhterev, "O polovom ozdorovlenii," Trudy s"ezda po bor'be s torgom zhenshchinami, vol. 1, p. 57.

[20] Robert Shikhman, "Tainaia prostitutsiia v S.-Peterburge," Trudy s"ezda po bor'be s torgom zhenshchinami, vol. 1, pp. 93–99.

[21] Di-Sen'i and Fon-Vitte, Vrachebno-politseiskii nadzor, p. 30.

[22] TsGIA, Gosudarstvennaia Duma, f 1278, op. 2, d. 3476, "Zhurnaly komissii po sudebnym reformam."

[23] Rossiiskoe obshchestvo zashchity zhenshchin v 1909 g., p. 52; Otchet popechitel'nago komiteta S.-Peteburgskago doma miloserdiia za 1910 g . (St. Petersburg, 1911), pp. 10–11.

not yet engaged in prostitution. None of the 379 women who registered in 1914 answered that they were not already earning money through prostitution.[24] There were also extremely high rates of venereal disease among women newly registering as prostitutes, often an indication of having engaged in commercial sex. Among first-time registrants in St. Petersburg in 1908, 213 (28 percent) of 756 women suffered from venereal disease. In 1909, the percentage rose to 37, or 199 of the 545 women who registered.[25]

Other statistics also substantiate the existence of widespread clandestine prostitution. In 1889, of 972 women stricken from the registration lists of the St. Petersburg medical-police committee, a full 550 (57 percent) "concealed themselves from surveillance" (ukryvshchikhsia ot nadzora ). The percentages of women in 1890 and 1895 were smaller—33 and 23 percent respectively—but they nonetheless bolstered allegations of extensive clandestine prostitution and reinforced fears about women engaging in commercial sex without any medical or police supervision.[26]

From one perspective, the yellow ticket offered several advantages over the unregulated street trade—safety, medical care, and a modicum of negotiating power. Possession of the license spared women from roundups following police raids of working-class neighborhoods. The yellow ticket also guaranteed free medical treatment for those women who contracted a contagious disease. (One reason why the rates of syphilis and gonorrhea were so high among first-time registrants was because the uncomfortable stages of syphilis and gonorrhea were often the precipitant to registration and subsequent free medical attention.) Without a license, prostitutes were more likely to need the aid of pimps and other protectors in order to stay free of the police. Moreover, if they were not registered, prostitutes were more vulnerable to extortion and other forms of exploitation from hotel managers and greedy landlords. The yellow ticket, purchased at the price of freedom, brought some maneuverability to an otherwise circumscribed life.

For most women, however, the price was too high. Registration meant that prostitution, which might previously have been a part-time venture, a means of supplementing meager earnings or bridging a spell

[24] Rossiiskoe obshchestvo zashchity zhenshchin v 1913 g. (Petrograd, 1914), pp. 101–2; Otchet o deiatel'nosti Petrogradskago doma miloserdiia za 1914 g., pp. 16, 20.

[25] Rossiiskoe obshchestvo zashchity zhenshchin v 1909 g., p. 54.

[26] Fedorov, Ocherk vrachebno-politseiskago nadzora, p. 46; Fedorov, "Deiatel'nost' S.-Peterburgskago vrachebno-politseiskago komiteta za period 1888–95 gg.," Vestnik obshchest-vennoi gigieny, no. 11 (November 1896): 185.

of unemployment, now became a full-time career. Lack of a passport made it difficult to earn money from anything but commercial sex. Any hopes to maintain a semblance of respectability had to be abandoned when a woman entered her name on police lists. Once registered, she became a public woman, the property of the state. Not only did clients have access to her body, so did policemen, committee agents, and physicians.

The yellow ticket virtually announced to a woman's community that she was working as a prostitute because it replaced her passport and kept her wedded to the local committee's examination schedule. Women not only feared the external stigma; many women did not wish to define themselves as prostitutes. Beyond medical-police control, a woman could tell herself that the prostitution in which she engaged, no matter how frequently, was temporary, that it was not her true profession. A law professor from Kazan University, Arkadii Elistratov, repeatedly heard women who had been threatened with legal action declare, "Do with me what you will, but I will not show up for medical examinations because I do not consider myself a prostitute."[27] The yellow ticket obliterated this self-definition. Its holders were unequivocally labeled "prostitute" and were required to live according to rules that differentiated them from the rest of the female population.

Vulnerable to venereal infections from clients, prostitutes were painfully aware of regulation's one-sided approach to disease prevention. This too soured them on nadzor. In 1909, a prostitute wrote a letter to the feminist Anna Miliukova about the necessity of subjecting clients to medical tests.[28] One year later, a member of St. Petersburg's Society for the Care of Young Girls (Obshchestvo popecheniia o molodykh devitsakh, hereafter OPMD) reported that the prostitutes she worked with at Kalinkin Hospital felt similarly. She recounted having heard several prostitutes declare that it was unfair to examine women only; it was their guests, not they, who were spreading disease. One said she could name a hundred men with syphilis whom no one had compelled to seek treatments.[29] At the 1910 All-Russian Congress for the Struggle against

[27] Elistratov, O prikreplenii zhenshchiny, p.39. In a recent BBC documentary, a woman who had just answered a Riga policeman's questions about her clients and her preferences still said no when he asked, "Do you consider yourself a prostitute?" Olivia Lichtenstein, "Prostitutki," BBC and WGBH production aired on the Arts and Entertainment network, May 26, 1991.

[28] "Pis'mo prostitutki, Soiuz zhenshchin, no. 4. (April 1909): 9–11

[29] Dement'eva, "Otritsatel'nyia storony," p.508.

the Trade in Women and Its Causes, a petition submitted by sixty-three prostitutes also addressed the inequity of a system that left syphilitic men, "whom it occurs to no one to examine," free to spread disease as they pleased. They complained that male syphilitic guests were permitted "to infect us without hindrance and without punishment, and eventually make us into unhappy cripples from whom anyone will turn away in horror. Indeed, our guests are not little children and they must understand that there is nothing to be proud of in spreading disease. They do not have the right to spread syphilis, not even to girls who walk the streets. We, too, are human beings who value our health; our old age will not be sweet without it."[30]

Nonetheless, observers often reversed the scenario: in most accounts it was the prostitute who willfully and maliciously infected her clients out of indifference or revenge. In Veniamin Tarnovskii's view, prostitutes had no scruples about damaging men's health; one rarely met a woman who would volunteer, "Stop me, I'm sick."[31] Aleksandr Kuprin's Iama, a popular fictional representation of brothel life, portrayed a syphilitic prostitute who repaid men for her fate by infecting them in return. "But I purposely infect these two-legged scoundrels. I infect ten, fifteen men every night. Let them rot, let them give syphilis to their wives, their lovers, their mothers. Yes, yes, also to their mothers and their fathers and their governesses, and even to their great-grandmothers. Let them all die, all those honest scoundrels!"[32] In White Slave: From the Diary of a Fallen Woman (Belaia rabynia: Iz dnevnika padshei zhenschiny ), the purported author proclaimed, "I'll infect anybody and everybody, I'll be a breeding ground of infection, but I'll take revenge." On the day after the new year of 1902, she tallied up her victims—one old man, two artisans, one merchant, and one young student.[33] The medical-police committee in the Amur region in 1910 was so woried about the danger presented by unregistered prostitutes that it petitioned the MVD for the right to subject those women found guilty of clandestine prostitution to martial law.[34]

Although many prostitutes with venereal disease may indeed have felt justified or smug about paying back a hypocritical society for their

[30] "Ot zhenshchin zanimaiushchikhsia prostitutsiei," Trudy s"ezda po bor'be s torgom zhenshchinami, vol. 2, pp. 511–12.

[31] Tarnovskii, Prostitutsiia i abolitsionizm, pp. 126, 157–60.

[32] Kuprin, Iama, p. 145

[33] Belaia rabynia: Iz dnevnika padshei zhenshchiny (Moscow, 1909), pp. 14–15.

[34] Vrachebnaia gazeta, no. 37 (1910): 1084.

fate, there were actually more practical reasons for a woman to continue to work the streets after she contracted an illness. Even Tarnovskii admitted that the early manifestations of disease could seem mild and that a woman facing hospitalization had to worry about the loss of her earnings and very likely her place to live.[35] Fear of contamination from ignorant and vindictive prostitutes nevertheless dominated contemporary images. The prostitute's hidden organs were perceived to function as the proverbial vagina dentata, with dangerous, mysterious infections serving as the deadly "teeth."

A certain element of fantasy made its way into educated society's impression of the ubiquity of prostitution. We can almost detect a note of longing in some descriptions of contemporary prostitution, as though observers secretly relished the idea of so much sex for sale. Robert Shikhman's characterization of clandestine prostitution in St. Petersburg fits into this category, as do his readings of some advertisements in local newspapers. To Shikhman, there was no doubt about what an "elderly and well-to-do gentleman" who had "lost the ability to take pleasure from life" had in mind when he advertised for "all sorts of services." His account of restaurant prostitution also had a salacious tone. "For a generous 'tip."' he wrote, prostitutes "are brought to the customer. The restaurant not only gives its guests a goblet from Bacchus, but one from Venus."[36]

Like bourgeois Parisians in the nineteenth century who could not really distinguish between the working classes and "less classes dangereuses, " Russian privileged society seemed to confuse all women who worked for a living with women who engaged in commercial sex. Mary Gibson's observations about Italian privileged society's response to female migration could apply equally to Russian women of the urban lower classes: the "nineteenth-century mind found it hard to conceive of any way to categorize these young, single, working-class migrants other than as prostitutes." Essentially, there was no way to understand women who were not under the "tutelage of men."[37]

In what was more than a metaphor equating wage labor with prostitution, claims surfaced throughout Europe that linked all working women with prostitutes.[38] An essay written by Aleksandr Fedorov in

[35] Tarnovskii, Prostitutsiia i abolitsionizm, p. 126.

[36] Shikhman, "Tainaia prostitutsiia," pp. 95, 99.

[37] Gibson, Prostitution and the State in Italy, p. 3.

[38] Alain Corbin has also suggested that there was much confusion between prostitutes and all women of the lower classes who catered to the needs of the bourgeoisie in nineteenth-century Paris. See Corbin, "Commercial Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century France," p. 215. In her study of domestic servants in eighteenth-century France, Sarah Maza argues that servants were suspected of prostitution because "if a defenseless woman sold her work in someone's household, might she not sell her body as well?" Sarah C. Maza, Servants and Masters in Eighteenth-Century France: The Uses of Loyalty (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983), p. 131.

preparation for an 1897 state conference on syphilis recommended medical inspections for "all women of the working class." As he put it the following year, "Whoever is familiar with factory life knows the utility and necessity of sanitary exams of factory women." Fedorov used another criterion to give credence to his suspicions. Revealing a stark vision of supply and demand, he argued that clandestines existed because the number of registered prostitutes was not "proportionate" to the male population.[39]

Several hundred physicians and tsarist officials attended the 1897 Congress for the Discussion of Measures against Syphilis in Russia (S"ezd po obsuzhdeniiu mer protiv sifilisa v Rossii), with the majority ruling that "Domestic servants make up a large component of clandestine prostitutes. In several cities, almost all domestic servants prostitute themselves."[40] This sentiment was echoed in congress proposals to institute physical examinations for all female domestic servants and women workers. In the eyes of participants at the congress, "clandestines" represented the greatest danger in terms of spreading venereal disease, and attendees made various proposals to compel prostitutes to register. Penalties for offenders included the shaving of their pubic hair by police-men, enclosure in a punishment room (as suggested by Warsaw's chief of police), and attaching a red stamp labeled puella publica to a prostitute's residence permit.[41] In 1899, when a commission was discussing ways to reform regulation in St. Petersburg, its members also proposed that examinations be extended to include all female workers.[42] Shikhman once remarked that the term "female factory worker" often served as a synonym in the lower classes for a debauched woman. His fellow ROZZh member admitted that they tried to keep women they had "rescued' away from factory labor because "women there generally fall."

[39] To protect the "modesty" of women who might be hesitant, Fedorov conceded that female nurses might be employed. Fedorov, "Deiatel'nost' S.-Peterburgskago vrachebno-politseiskago komiteta," p. 194; Fedorov, Ocherk vrachebno-politseiskago nadzora, pp. 56, 58, 64.

[40] "Protokoly obshchikh zasedanii," p. xviii.

[41] Elistratov, O prikrepelenii zhenshchiny, p. 365.

[42] "Protokol zasedaniia sanitarnoi komiissii s priglashennymi spetsialistami 12 noiabria 1899 g.," in Otchet S.-Peterburgskoi gorodskoi ispolnitel'noi sanitarnoi komissii za 1899 g. (St. Petersburg, 1900), p. 434.

Even an administrator from the House of Mercy claimed that the "majority of women in the trades engage in clandestine prostitution."[43]

Aside from the wealthier, professional prostitutes who paid the requisite bribes to maintain their freedom from the police, it is unlikely that so many full-time prostitutes could have remained beyond the police's reach indefinitely. Dr. Petr Oboznenko, a student of Tarnovskii and the author of a major study of St. Petersburg prostitutes, questioned the assumption of widespread clandestinity among women workers. Oboznenko doubted that so many "simple peasants" could have eluded the police quite so successfully. Rather, many had fallen through holes in the bureaucratic sieve and had done nothing more than return to their village, find work elsewhere, or get married. Oboznenko also doubted that most working women doubled as prostitutes. Servants, for example, maintained such demanding duties and schedules that it would have been extremely difficult to find the time or privacy to engage in prostitution. A high percentage of prostitutes indeed listed domestic service as their former occupation, but this did not necessarily indicate that they had held their jobs simultaneously with their work as prostitutes. As for factory workers, how could a woman succeed as a prostitute after working a typical twelve- to fourteen-hour day in the factory? On the other hand, Oboznenko acknowledged that tradeswomen, chorus girls, ballerinas, sales clerks, and others who supplemented their income with prostitution could remain outside medical-police surveillance because they avoided the areas where police agents tended to focus their raids. Neither vagrant nor destitute, they had permanent addresses and often held regular jobs. They could stay free of the regulatory system by visiting private physicians when they required medical treatment and bribing bothersome police agents to leave them alone.[44]

The truth about clandestinity lies somewhere between the polarized visions of women as prostitutes or innocents. Seasonal layoffs, unemployment, and low wages could impel many women workers to supplement their income with occasional prostitution. Oboznenko overlooked the fact that "prostitution' was a broad and flexible trade. Though servants and factory women indeed labored long hours and had few opportunities to walk the streets during the workday, the workplace itself of-

[43] Shikhman, "Tainaia prostitutsiia," p. 108; N. Fon-Guk, "Sluchai pokhishchenii zhenshchin v Peterburge," Peterburgskaia gazeta, no. 199 (July 22, 1908): 2; Serafima I. Konopleva, "Otdelenie dlia nesovershennoletnikh S.-Peterburgskago doma miloserdiia," Trudy s" ezda po bor'be s torgom zhenshchinami, vol. 1, p. 307.

[44] Oboznenko, Podnadzornaia prostitutsiia v Peterburge po dannym vrachebno-politseiskago komiteta i Kalinkinskoi bol'nitsy (St. Petersburg, 1896), pp. 15–16, 40–41.

ten provided ample opportunities to pick up extra cash or favors. Casual prostitution may have assumed many forms, from repaying men with sex for dinners and presents, to occasional stints on the street in order to earn extra money. Certainly, all women understood that the promise of sex, implicit or otherwise, gave them leverage and helped them exact favors or gifts from men. Christine Stansell's contention that for poor women in nineteenth-century New York City, prostitution was not a "radical departure into alien territory" in light of its "resemblance . . . to other ways of dealing with men" might also hold for Imperial Russia.[45]

Sincere but moralistic reformers could easily confuse sexually selfconfident, independent, young women with prostitutes, forgetting that a line divided professional prostitution from casual sex. Like the Petersburg agent who mistook the cigarette-smoking, loud-mouthed daughter of a state official for a "nocturnal butterfly," observers might identify any sort of assertive behavior or provocative dress as a sign of prostitution. Kathy Peiss suggests that we "reach beyond the dichotomized analysis of many middle-class observers." Her study of young working-class women in New York at the turn of the century reveals that many exchanged sexual favors for opportunities to indulge in the pleasures that city life offered them. These "charity girls" were not clandestine prostitutes, but neither were they the respectable paragons of virtue that middle-class observers sought to find. "Working women's public behavior often seemed to fall between the traditional middle-class poles: they were not truly promiscuous in their actions, but neither were they models of decorum."[46]

Critics of the regulatory process charged that the practice of arresting female vagrants as possible clandestines occasionally backfired, creating prostitutes rather than exposing them. Oboznenko sensitively described the psychological vulnerability of a young woman without a home or job who might be swept into the net of one of Petersburg's police raids. Compelled to spend the night in the company of seasoned professionals, she could easily be influenced among such well-fed and elegantly dressed women, particularly because some might attempt to recruit her. In this environment, it would become painfully obvious that she too

[45] Stansell, City of Women, p. 180.

[46] Kathy Peiss, "Charity Girls' and City Pleasures: Historical Notes on Working-Class Sexuality, 1880–1920," in Powers of Desire: The Politics of Sexuality, ed. Ann Snitow, Christine Stansell, and Sharon Thompson (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1983), p. 75. See also Rosen, The Lost Sisterhood, pp. 42–45.

might enjoy such material comforts. Police officials might aggravate the situation by advising her that she could avoid future arrests simply by accepting a yellow ticket.

Oboznenko wrote that most women resisted this path, refusing to register and resuming their struggle to survive by virtue of "honest labor." But if they remained without work, invariably they would once again be brought into police custody to relive the scenario of envy and temptation. The more desperate a woman felt, the more probable it was that several arrests would convince her to accept what seemed to be her inevitable fate, full-time prostitution. By the same token, if St. Petersburg's medical-police committee found a woman to suffer from any sort of vaginal ailment—even simple lice or some kind of vaginal inflammation—she would be brought to Kalinkin Hospital and housed with experienced prostitutes, some of whom were rewarded by brothelkeepers for finding fresh recruits. Upon their discharge from the venereal ward, many women would sign right up on committee lists. Bentovin agreed that Kalinkin itself created professional prostitutes, dubbing its section for women with venereal disease a "prep ward" (prigotovitel'nyi passion ).[47]

As Fedorov put it, the role of medical-police committee agents consisted of "keeping an eye on all women of very loose morality who furnish grounds for suspicion of trading their sexual pleasures." Agents supposedly adhered to elaborate rules for confirming their impression, first monitoring a woman's behavior to find out whether their suspicions were founded. This involved following her home and "cautiously" interviewing the doorman or concierge of the building about her comings and goings. Depending on the interview's outcome, the medical-police committee would decide whether to "invite" her for a medical examination or simply place her under further surveillance. If an examination was prescribed and the woman refused to appear, she was liable for prosecution. She was likewise prosecuted if the committee asked her to register and she refused. In Fedorov's view, however, the courts tended to be lenient, penalizing reluctant women with "only" a one- or two-ruble fine.[48] Though a certain number of checks and balances were

[47] Oboznenko, Podnadzornaia prostitutsiia, pp. 33–37; Bentovin, "Torguiushchiia telom," Russkoe bogatstvo, no. 11 (November 1904): 92; A volunteer at Kalinkin Hospital told of a woman in the prostitutes' ward who continually talked about the good life at her brothel. As it turned out, this woman was a recruiter paid by a brothelkeeper to secure new residents. Dement'eva, "Otritsatel'nyia storony," p. 507.

[48] Fedorov, Ocherk vrachebno-politseiskago nadzora, pp. 6, 34–35.

built into the committee's procedures, it is easy to see opportunities for abuse, harassment, and impropriety.

As we saw earlier, numerous instances involving false arrests continually came to light, prompting discussions among officials on how to reform the process of registration. But in fact the problem was inherent to the agents' assignment. Expected to bring unregistered prostitutes under medical-police control, agents needed to exercise a certain freedom of movement and judgment. It was up to them to draw the very ambiguous line between apparently immoral behavior and actual prostitution. Even an MVD commission admitted, "it is difficult to establish in individual cases where the border lies between an immoral way of life and the trade of prostitution."[49] Untrained and underpaid, agents used the power they wielded in working-class neighborhoods to solicit bribes and sexual favors. Confusion over who was and who was not a prostitute did not originate with medical-police agents. They naturally took their cues from their superiors, who, as we have seen, suspected all working women of engaging in clandestine prostitution.

Examinations

The examination itself cannot trouble them in the least, as is possible to see by the ease with which they undergo it.

Dr. Aleksandr Fedorov (1897)

In 1904, the MVD received a complaint from the military governor of Irkutsk asserting that troop movements in the Russo-Japanese War had caused an increase in prostitution and venereal disease rates in the areas along the Trans-Siberian railway. With no special facilities in which to examine these women, the Krasnoiarsk medical-police committee held examinations in the local hospital, giving rise to all sorts of problems. According to the report, the prostitutes were often drunk, creating "an extremely unpleasant impression on passers-by." They also violated "the peace of other patients with their loud conversations, abusive language, and occasional fighting." When they left, there remained behind "a great deal of rubbish, including the heap of rags with which

[49] TsGIA UGVI, f. 1298 op. 1, .d. 2332, "Doklad kommisii."

they wipe themselves prior to their medical examinations."[50] In Narva, the scenario was reversed, but no less disturbing to local authorities. There, when prostitutes visited the municipal physician for their exams, they faced "derision and even insults from the curious crowd." The prostitutes also aroused "undesirable curiosity" among high school students on their way to and from classes.[51]

Despite Fedorov's sanguine remark about "the ease with which [prostitutes] undergo" their examinations, most accounts suggest that obligatory medical inspections were extremely odious for the women who endured them. At best they were terribly inconvenient. At worst they not only left women feeling ashamed and deeply degraded, but functioned to spread rather than curb venereal diseases. Lined up and looked over like cattle in the stockyards, prostitutes might well have felt more dehumanized by medical-police physicians than they did by their customers. Prostitutes in Kalinkin Hospital told a member of the OPMD that they found examinations terribly burdensome, especially the first few times. Examinations, they complained, were conducted crudely, with no attention to "female modesty." Several found them so mortifying that they needed to get drink before they could face committee physicians.[52]

A look at the circumstances under which most women underwent their medical inspections not only confirms the prostitutes' characterization, but impugns the regulators' claims of preventing the spread of venereal disease. Whereas Moscow's Women's Municipal Free Clinic examined only 45 women in three-hour shifts, Petersburg doctors often saw between 200 and 400 women in a mere four hours' time.[53] That meant each prostitute received perhaps a minute of medical attention. It is difficult to believe that a physician could conduct the required examination of a woman's internal and external genitalia, her anus, as well

[50] The women probably wiped themselves to remove vaginal discharges that could be diagnosed as gonorrhea. TsGIA, Glavnoe upravleniia po delam mestnago khoziaistva (hereafter GUDMKh), f. 1288, op. 12, d. 1622, letter of September 28, 1904.

[51] Tsentral'nyi Gosudarstvennyi Arkhiv Leningradskoi Oblasti (hereafter TsGALO), Vrachebnoe otdelenie S.-Petersburgskago gubernskago upravleniia, f. 255, op. 1, d. 852, letter from police chief of July 8, 1905.

[52] Dement'eva, "Otritsatel'nyia storony," p. 508.

[53] Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia v gorodakh," pp. 41–42. During World War I, a United States colonel who was investigating regulation in France reported having seen a Bordeaux physician examine fifty-nine prostitutes in one hour and a Cherbourg physician examine fifteen in just thirteen minutes. George Walker, Venereal Disease in the American Expeditionary Forces (Baltimore, 1922), pp. 84–89, in Brandt, No Magic Bullet, p. 100.

as her nose, mouth, and throat in so short a time.[54] Most likely, the doctors just took a quick glance at each patient's vulva to see whether there were any sores or other readily apparent signs of sexually transmitted diseases.

The main clinic in St. Petersburg sat upstairs from medical-police committee headquarters in the Rozhdestvo district, while the remaining two clinics were located in other parts of the capital. The Rozhdestvo clinic had access to hot water, but the other two obtained it by boiling water in a "common kitchen cauldron."[55] With such an overload of patients, the medical staff routinely failed to follow standard hygienic procedures. It was also easy for them to overlook more subtle forms of contagious diseases. Committee doctors themselves admitted it was impossible to diagnose a disease accurately, let alone observe the most rudimentary sanitary precautions, such as washing their hands and rinsing vaginal speculums (even in cold water) between patients. Clinics were so crowded and inspections so brief that Petersburg prostitutes sometimes merely lifted up their dresses for their "examinations."[56]

The Petersburg clinics also provided very little in the way of comfort for the stream of patients.[57] The Women's Municipal Free Clinic in Moscow had a rug covering the floor and a cloak room for outer garments, but Petersburg's clinics lacked both; when the weather was rainy or cold, women there would be examined in their coats and galoshes. Dr. Konstantin Shtiurmer, a medical-police official who reported on the workings of nadzor to the syphilis congress in 1897, characterized Petersburg prostitutes as "completely undisciplined." In the cramped quarters of St. Petersburg's clinics, prostitutes, many of whom arrived drunk or

[54] Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia," pp. 470–71; Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia v gorodakh," p. 40.

[55] Fedorov, Ocherk vrachebno-politseiskago nadzora, p. 43.

[56] Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia v gorodakh," p. 40; Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia," p. 471; Bentovin, "Torguiushchiia telom," p. 157; Fedorov, Ocherk vrachebno-politseikago nadzora, pp. 39–43. Russian doctors were not the only ones lax in this regard. Prior to World War I, Abraham Flexner witnessed a Paris physician "examine 25 or 30 girls without changing, washing, or wiping the rubber fingers he wore." Flexner, Prostitution in Europe, p. 217.

[57] Several St. Petersburg outpatient venereal clinics also earned "unsatisfactory" ratings, according to municipal council reports, with three suffering from poor ventilation, excessive noise, and lack of light. Kalinkin's outpatient facility was so small that patients had to stand outside the hospital on Libavskii Lane. (As many as 81,613 patients visited Kalinkin for outpatient care in 1897.) "Ob organizatsii ambulatornago priema sifiliticheskikh, venericheskikh, i kozhnykh bol'nykh," Izvestiia S.-Peterburgskoi dumy, no. 24 (August 1899): 648-51; "O prizrenii sifiliticheskikh, venericheskikh, i kozhnykh bol'nykh v S.-Peterburge," Izvestiia S.-Peterburgskago gorodskoi dumy, no. 15 (August 1898): 321.

hung over, had no choice but to mill around the corridors. Given the terrible crowding, it was no surprise that patients were known to faint and that misconduct of all kinds—from pushing, cursing, and fighting, to urinating on the floor—was common.[58]

The chaos was rivaled only by the filth. In 1912, Dr. Poliksena Shishkina-Iavein, a leading member of the All-Russian League of Equal Rights for Women, having investigated the city's facilities, complained to The Evening Times (Vechernee vremia ) that all three of the capital's clinics were in appalling sanitary conditions. Each was damp, dirty, and too dark to permit careful examinations during Petersburg's long winters.[59]

It is no great wonder that registered prostitutes avoided examinations as often as they could, in spite of surveillance by medical-police agents. Fedorov tallied attendance rates for Petersburg's clinics in his 1897 Study of Medical-Police Surveillance of Prostitution in St. Petersburg (Ocherk vrachebno-politseiskago nadzora za prostitutsie v S.-Peterburge ). According to his calculations, odinochki had to appear at least forty times a year and brothel prostitutes would have seen physicians in their brothels at least eighty times.[60] But the actual number of exams given fell far short of the required numbers. For example, the committee reportedly carried out 134,319 instead of the targeted 237,480 exams in 1883, the year the ranks of registered prostitutes had reached 4,700. Even in the best year for exams, 1872, Only 133,761 out of a required 160,760 had been administered.[61] Petr Oboznenko, who also worked for the committee, counted a mere 150 women in St. Petersburg who showed up regularly for their examinations, most of them prostitutes who had been on the police lists for more than five years. Approximately two-thirds of the registered prostitutes would appear twice a month, that is, for only half the required number of examinations. Of the remaining third, 100 to 200 women would appear only once or twice a year, and another 450

[58] Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia v gorodakh," p. 40.

[59] When a commission appointed by the UGVI investigated Shishkina-Iavein's allegations, its members found that the rooms were indeed small and that proper ventilation was lacking. This commission pointed out, however, that electric lamps and windows did in fact provide adequate illumination. See G—llo, "Zloupotrebleniia," p. 3; TsGIA, UGVI, f. 1298, op. 1, d. 2332, "Doklad kommisii."

[60] Although a once weekly appearance was required for odinochki, Fedorov presumably subtracted twelve from fifty-two in order to account for twelve menstrual periods. For brothel prostitutes, the number was simply doubled because they were examined twice a week.

[61] Fedorov, Ocherk vrachebno-politseiskago nadzora, pp. 6–7. Fedorov miscalculated this last number, thereby reducing the gap of 26,999 to a less extreme 6,999 exams.

to 775 not at all. As early as 1896, Oboznenko noted that the group of "no-shows" was growing, partly because supervisory personnel was lacking, but also because many women were registering with the medical-police committee simply to avoid being arrested for clandestine prostitution. These women would keep their yellow ticket, but they would not fulfill the obligations that accompanied registration.[62] Even if women came for their exams, their presence did not necessarily guarantee further cooperation.

In 1909, a report from the St. Petersburg medical-police committee to the UGVI echoed Oboznenko's analysis. That year the committee noted that the number of examinations administered to odinochki was dropping; 401 of the capital's registered prostitutes failed to show up for a single examination. According to this report, only a third of St. Petersburg's registered odinochki would appear more or less regularly. The rest would appear "when they feel like it." In many cases, women would show up five or six times and then disappear from committee view, shielded, the committee believed, by their landladies and pimps.[63] (Of course, the clinics were already overcrowded. Had all the women on medical-police lists attended regularly, conditions would have been even more intolerable.)

Though the clinics in St. Petersburg sound dreadful, the facilities were still far superior to those used by most doctors and policemen for the regulation of prostitution. In fact, most cities had no medical-police clinics whatsoever. In 1897, basing his report on descriptions by local officials, Shtiurmer evoked a horrific image of the medical side of regulation for his colleagues at the 1897 congress. Because they lacked funding for medical facilities and equipment, most officials, policemen, and doctors made do with what was already at hand when they followed MVD instructions. According to Shtiurmer, prostitutes in the city of Baku were examined in the police station on a tattered lounge or on a table borrowed from another office. Prostitutes awaited their turn to-

[62] Oboznenko, Podnadzornaia prostitutsiia, p. 46. Upon examining medical-police reports from Russia's cities prior to the 1897 congress on syphilis, Konstantin Shtiurmer discovered that some officials recorded the number of annual examinations administered to prostitutes simply by multiplying the number of registered prostitutes by the number of examinations required. That is, if 100 prostitutes were expected to undergo one examination every week, a district physician might dutifully (albeit wrongfully) report that 5,200 exams had been conducted. Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia v gorodakh," pp. 48–50.

[63] These figures are from TsGIA, UGVI, f. 1298, op. 1, d. 1730, "Otchet inspektora meditsinskoi chasti S.-Peterburgskago vrachebno-politseiskago komiteta za 1910 g."

gether with the usual "motley public" (raznosherstnaia publika ) and, according to officials in Baku, were often too "ashamed" to arrive sober.[64] From Saratov officials, Shtiurmer learned that prostitutes in brothels were examined on simple tables. They would undress, mount the table and, because no speculum was available, spread their own vaginal lips (sometimes concealing venereal sores with their fingers). In Orel, prostitutes were examined in a small, damp, poorly lit room in the local police station. In Nikolaevsk and Tula, policemen brought prostitutes into prison cells for their examinations. In Astrakhan, women were examined on a wooden chair by doctors who lacked medical instruments.[65] Physicians in the Baltic city of Revel' (now Tallinn) also had no special medical equipment for internal examinations. They examined prostitutes in a small, unheated room. Warsaw's medical-police committee until just prior to the congress had conducted examinations of prostitutes in a dark basement in the humiliating presence of several policemen. Shtiurmer referred to the conditions in Zamost' as "revolting." From the district doctor's report, he discovered that examinations took place in a ground-floor room whose window faced the street. When prostitutes would come for their weekly examinations, a crowd of spectators would gather on the street to peek through the open window and jeer.[66]

Thirteen years later, an official MVD publication entitled Medical-Police Surveillance of Urban Prostitution (Vrachebno-politseiskii nadzor za gorodskoi prostitutsiei ) showed that many doctors were still conducting examinations in dark, makeshift, and underequipped locations like cellars, city jails, flophouses, and even in morgues. A medical inspector's report from Astrakhan set the tone with its description of a "decrepit" building with a leaky ceiling and tattered, vermin-infested wallpaper. During the winter, temperatures in the (unheated) examination room would fall so low that the doctor would leave on his coat while inspecting local prostitutes.[67] Such surroundings no doubt added to the discomfort and humiliation of local prostitutes, as well as to the tremendous resistance they displayed toward medical-police obligations.

[64] Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia v gorodakh," p. 46.

[65] Ibid., pp. 44–46. According to an 1891 Medical Department report, the Astrakhan city council withheld funding from local regulation. Otchet Meditsinskago departamenta, p. 178.

[66] Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia v gorodakh," pp. 42, 44–46.

[67] Di-Sen'i and Fon-Vitte, Vrachebno-politseiskii nadzor, p. 35.

In 1912, Dr. Shishkina-Iavein charged that a housekeeper at the Rozhdestvo clinic had been accepting bribes from prostitutes for help in covering signs of disease.[68] Stories abounded of prostitutes who tried to fool doctors by covering venereal lesions with their fingers or spreading a cauterizing substance like silver nitrate on them. Others might simply squeeze the pus from festering sores prior to examinations. Oboznenko claimed that all experienced prostitutes knew how to mask the symptoms of gonorrhea when the infection was not too far advanced. One medical journal admitted that prostitutes often inserted a tampon-like wad of cotton in their vaginas before examinations in order to absorb telltale discharge. Urination just prior to examination was also believed to hide signs of gonorrhea.[69] In her book on prostitutes in nineteenth-century Paris, Jill Harsin mentions that women would cover lesions with fake beauty marks and patch their genitals with various powders and pastes. To mask ulcers in their mouths, prostitutes would eat chocolate before they were seen by committee doctors.[70] Because the initial symptoms of venereal disease could be so mild, many prostitutes would simply avoid committee doctors until their illness reached a more uncomfortable stage—as indicated by festering sores and intense pain.

Such subterfuge on the part of a prostitute is understandable. From her point of view, what good would come of these examinations? If the doctors found no sign of venereal disease, she would be sent back to the streets to resume her trade. If not, she had to endure several weeks or months of incarceration in a locked hospital ward. This meant not only the deprivation of freedom, but loss of her wages, regular clients, and place to live. Viewed in this light, reports of how assiduously prostitutes tried to avoid registration and examinations become more comprehensible, as does their rebellious behavior in clinics and hospitals.

[68] When a commission organized by the UGVI investigated this allegation, its members found that an ex-prostitute at the Narva clinic had been prosecuted for such a practice. But the Rozhdestvo clinic was an unlikely place for such an abuse because only one physical space was available: a tiny, dark dressing room in constant use. A woman did sit in attendance, but she was not the housekeeper, only the wife of the watchman, and too uneducated to assist prostitutes in disguising their symptoms. G- —llo, "Zloupotrebleniia," p. 3; TsGIA, UGVI, f. 1298, op. 1, d. 2332, "Doklad kommisii."

[69] A. D. Suzdal'skii, "K voprosu ob uporiadochenii prostitutsii v Smolenske," Meditsinskaia beseda, no. 22 (November 1900): 649; Oboznenko, Podnadzornaia prostitutsiia, pp. 50–51; Russkii zhurnal kozhnykh i venericheskikh boleznei, no. 11 (November 1903): 655.

[70] Harsin, Policing Prostitution, p. 271.

Hospitalization

It's a Monday come about.

A discharge is to come my way.

Doctor Krasov won't let me out.

Well, the devil can make him pay.

Sung by the prostitutes in Iama

In the spring of 1912, Petersburg's medical-police committee beseeched the municipal duma to fund carriages for transferring prostitutes from the city's clinics to Kalinkin Hospital. Apparently, medical-police agents marched their reluctant wards on foot from the city's clinics, giving rise to all kinds of unpleasant displays. Some prostitutes would break ranks, now having "the full opportunity to spread venereal disease." Others would make the best of a bad situation by insulting the agents and accosting passers-by. Prostitutes might also duck into taverns en route to Kalinkin, where they would "hastily drink beer and wine, become drunk, and then create disgraceful scenes." The sight of prostitutes and agents walking through the capital's streets, said one observer, presented an "ugly spectacle, insulting to public morality." Not surprisingly, the daily parade inspired mockery and harassment from onlookers. "[I]t is only with the greatest difficulty," lamented the committee, "that [the prostitutes] are delivered to the hospital."[71]

The regulatory system rested on the belief that the removal of contagious prostitutes from circulation would reduce the spread of venereal disease: logic demanded that these women be locked up. But mandatory hospitalization posed a whole new set of problems, for prostitutes deeply resented their internment in locked hospital wards. By and large, their cases of syphilis and gonorrhea could have been treated at outpatient facilities. Instead, prostitutes had no choice but to face extended stays in institutions that were uncomfortable and painful under the best of circumstances, fatal under the worst. Meanwhile, whatever sort of domestic stability they may have achieved in terms of their neighborhoods and communities, their friendships and romantic relationships, and their households and residences, underwent an abrupt break.

Understaffing and overcrowding were problems for Russian hospi-

[71] "Po otnosheniiu S.-Petersburgskago gradonachal'nika ob ezhednevnom otpuske v rasporiazhenie vrachebno-politseiskago komiteta," Izvestiia S.-Peterburgskago gorodskoi dumy, no. 8 (February 1913): 1744–47. Only the weakest prostitutes were transported to Kalinkin in a cab; the others walked. Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia v gorodakh," p. 35.

tals in general; it is not surprising that special venereal wards for prostitutes were similarly affected.[72] Although Kalinkin Hospital was indisputably the best facility of its kind in Russia, venereal patients were still known to sleep two to a bed, and it was not uncommon to place patients in corridors and dressing rooms.[73] At the end of the nineteenth century, Kalinkin's chief doctor reported to the Petersburg duma that second-floor patients had less than four cubic meters of air per person and that first- and third-floor patients had less than two. In this stifling environment, he pointed out, syphilitic patients undergoing treatments with the disease's primary cure, mercury, could become especially uncomfortable. Many syphilitic patients were receiving mercurial unctions; the noxious fumes given off by the ointment on their bodies were believed to compromise the health of other patients.[74] No doubt the malodorous smoke emitted by nearby factories added to the unsavory environment. In 1882, the municipal administration declared the century-old Kalinkin decrepit and not in conformance with standards of hygiene. That same decade, a Petersburg physician made reference to the likelihood that diseases were spreading within the hospital by unsanitary medical instruments and utensils, and the proximity of contagious patients.[75]

As of January 1, 1907, there were 8,143 available hospital beds in all of St. Petersburg, with 10,460 patients occupying them. On that date in Kalinkin Hospital, 507 beds held 589 patients. Patients throughout the northern capital slept in corridors, cafeterias, and operating rooms on couches, benches, and even floors.[76] When the prostitutes' ward in Kalinkin was full, prostitutes might be sent to other women's sections, in spite of their reputation for singing dirty songs, playing bawdy games, and corrupting "respectable" female patients. According to one outraged source, prostitutes could even be found interned among syphilitic children.[77]

At Kalinkin, a frugal 15 kopecks a day went toward feeding each in-

[72] Results of a survey organized by Dmitrii Zhbankov on the state of hospital care were published in 1903. His study showed that while the major cities had hospitals, these were insufficient to meet the population's needs. A. A. Chertov, Gorodskaia meditsina v evropeiskoi Rossii (Moscow, 1903).

[73] Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia v gorodakh," pp. 52, 55.

[74] "O prizrenii sifiliticheskikh, venericheskikh, i kozhnykh bol'nykh," pp. 324–25.

[75] Kapustin, Kalinkinskaia gorodskaia bol'nitsa, pp. 15, 22, 33, 93–94.

[76] TsGIA, GUDMKh, f. 1288, op. 13, d. 4., "Ob organizatsii bol'nichnago dela v S.-Peterburge 1907–1913 gg."

[77] Oboznenko, Podnadzornaia prostitutsiia, p. 54; Bentovin, "Torguiushchiia telom," p. 92; Novoe vremia (October 27, 1899), cited in Vrach, no. 44. (1899): 1315.

mate. In 1881, a typical breakfast at Kalinkin consisted of bread, tea, and sugar. For dinner, patients received some kind of soup with roast meat and cutlets or milk, and for their evening meal, porridge made from buckwheat, barley, or wheat. On meatless Fridays, patients could anticipate pea soup and buckwheat porridge for their midday meal, followed by wheat porridge for supper. Because many prostitutes had become accustomed to rich food and plenty of wine and vodka, the spartan, monotonous diet in the hospital contributed to their restlessness.[78] In 1899, a Professor Smirnov suggested to the St. Petersburg duma that prostitutes housed in Kalinkin Hospital ought to receive even poorer quality food than its other inmates.[79] Smirnov, like many others involved in the medical-police regime, evidently saw venereal disease and incarceration as a prostitute's just deserts.

The hospital in Revel' provided a mere ten beds for prostitutes in "one pitiful room, badly illuminated by daylight, extremely filthy, and steeped in soot from lamps and all sorts of fumes."[80] In 1901, a journal of venereal medicine described Moscow's Miasnitskaia Hospital as dirty, unventilated, and overcrowded. According to this account, Miasnitskaia housed more than 400 patients in its facilities for 300.[81] The same year, a report on Martynov Hospital in Nizhnii Novgorod characterized it as damp, dirty, and uncomfortable. During the busy summer season, prostitutes there were sometimes housed two to a bed, forcing the administration to turn away ailing prostitutes for lack of space. In these cases, the local committee would ask brothelkeepers to sign a paper (dubiously) guaranteeing a diseased prostitute's sexual abstinence.[82] A clinic doctor noted that a new record player and a supply of books had been appreciated, but the fact that many women had traveled to this city only to take advantage of the annual fair created major problems, for these women resented their confinement more than ever. "The desire to be discharged sooner manifested itself in several [patients] so vehemently and was accompanied by such disgraceful escapades," reported a local physician, "that sometimes it was even necessary to resort to the help of the police."[83] Shtiurmer mentioned one city that had diagnosed 151

[78] Kapustin, Kalinkinskaia gorodskaia bol'nitsa, pp. 5, 41.

[79] Novoe vremia (October 27, 1899), cited in Vrach, no. 44 (1899): 1315.

[80] Elistratov, O prikreplenii zhenshchiny, p. 221.

[81] "O Miasnitskoi bol'nitse dlia kozhnykh i venericheskikh bol'nykh," Russkii zhurnal kozhnykh i venericheskikh boleznei, no. 7 (July 1901): 215.

[82] Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia v gorodakh," p. 57.

[83] Ezhenedel'nik zhurnala "prakticheskoi meditsinoi," no. 12 (1901): 223; Chagin, "Otchet po Nizhegorodskoi iarmarochnoi zhenskoi bol'nitse," p. 173.

prostitutes as having venereal disease within a five-year period; only three of these women admitted themselves to the local hospital.[84]

As for the free care guaranteed by medical-police committee rules, this too did not necessarily hold. In Kharkov, prostitutes had to contribute a full 25 rubles insurance annually to guarantee themselves an available hospital bed. Prostitutes paid for care in many other cities as well. A 1903 MVD directive stipulated that hospitalization of venereally diseased prostitutes was an absolute requirement, but some cities permitted prostitutes to be treated at home. Although prostitutes no doubt bribed doctors for this privilege, shortage of space in hospitals remained the determining factor.[85] When participants at the 1897 congress on syphilis discussed a resolution forbidding hospitals from refusing to admit syphilitics in the disease's infectious stage, they wound up voting it down as unrealistic. What would happen, one physician asked, if a hospital had no available space?[86]

Shtiurmer blamed the chronic shortage of beds for the practice of discharging diseased prostitutes prematurely. Medical authorities believed that syphilis could require months if not years of treatment, yet prostitutes in Russia averaged only five and a half weeks in the hospital. Moreover, the hospital staff tended to release prostitutes long before they were considered fully cured. Shtiurmer complained that medical-police physicians daily found signs of venereal disease on prostitutes who had just been discharged from Kalinkin. These women would be dispatched right back to the hospital.[87]

If hospitalization, marked as it was by confinement and tedium, resembled imprisonment, medical treatment represented nothing less than punishment and torture. Women who suffered from gonorrhea had to endure painful cauterization treatments that, as we now know, tackled the symptoms, not the disease. As for syphilis, prior to 1910 the most common remedy consisted of a prolonged series of mercurial injections.[88] Mercury essentially poisoned the entire organism. It could kill off syphilis's spirochetes and thereby suppress clinical manifestations

[84] Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia v gorodakh," pp. 47–51, 59.

[85] Ibid., pp. 36–37, 57–58.

[86] "Protokoly obshchikh zasedanii," pp. 70–72.

[87] Shtiurmer, "Prostitutsiia v gorodakh," pp. 52–53, 55.

[88] As late as 1912, a Tomsk physician reported that he was using mercurial injections to treat syphilitic patients. V. M. Timofeev, "Otchet po svidetel'stvovaniiu prostitutok v g. Tomske za 1912 g.," Vrachebno-sanitarnaia khronika g. Tomska, nos. 8–10 (August–October 1913): 485.

of the disease, but it did not necessarily effect a cure.[89] A brothel musician recalled how after these injections "lumps bigger than walnuts" would appear on a woman's legs, so that "for a long time the poor thing could neither walk, lie down, nor sit."[90] In Nizhnii Novgorod, syphilitic prostitutes were injected in the buttocks with a compound of mercury and salicylic acid (hydrargyrum salicylicum ) every four days. Patients there, a resident physician admitted, "very frequently" complained of pain and suffering from inflammation at the injection site.[91]

We may also question the quality of Russia's various medications and their distribution throughout the huge empire. On the advice of Veniamin Tarnovskii, Petr Gratsianov of Minsk's sanitary commission relied on the Fridlander Pharmacy in distant St. Petersburg for his solution of salicylic acid and mercury.[92] If Minsk's pharmacies could not be trusted for the careful filling of such a delicate prescription, could the availability of reliable medical preparations have been better in the rest of Russia?

Severe salivation, often measured by the pint, was one of the mercury treatment's least unpleasant side effects. Others included severe gastro-enteritis, weakness, anemia, depression, liver and kidney disease, and loss of teeth. When the patient's gastrointestinal tract "could stand no more," injections could be replaced by ointments made from mercury in a base of suet and lard. These were gentler to the human organism, but they promoted skin diseases and caused great embarrassment because of their smelly, ghastly blue-gray sheen.[93] The "cure" could also prove worse than the disease, with some patients dying of mercury poisoning. It is no wonder that many syphilitics were reluctant to place themselves in the hands of Russia's doctors.

Although many registered prostitutes accepted their fate passively, some responded with outright rebellion and others could be stirred to resist under certain conditions, such as not being released on the day they expected.[94] In 1897, Anna Kaliagina, a 22-year-old prostitute, fractured her leg and injured her back when she attempted to escape

[89] John T. Crissey and Lawrence C. Parish, The Dermatology and Syphilology of the Nineteenth Century (New York: Praeger, 1981), p. 366.

[90] A. I. Shneider-Tagilets, Zhertvy razvrata: Moi vospominaniia iz zhizni zhenshchinprostitutok (Ufa, 1908), p. 8.

[91] Chagin, "Otchet po Nizhegorodskoi iarmarochnoi zhenskoi bol'nitse," p. 172.

[92] Gratsianov, "Desiat' let sanitarnago nadzora za prostitutsiei v g. Minske," Russkii meditsinskii vestnik, no. 15 (August 1, 1903): 19.

[93] Crissey and Parish, The Dermatology and Syphilology of the Nineteenth Century, pp. 360–62.

[94] Bentovin, "Torguiushchiia telom," p. 89.

through the second-story window of a hospital in Kazan. Kaliagina explained that she had no desire to remain locked in a hospital when she felt perfectly healthy. Two years later, at the same hospital, twenty prostitutes shut themselves in and smashed windows and dishes. Eight of these women were arrested.[95] A similar incident occurred in June 1898 when prostitutes at the Mariupol' city hospital attacked the medical staff, broke windows, and tossed out "everything they could get their hands on." According to the local newspaper, the ruckus began when a prostitute who was scheduled to undergo medical treatment began shouting. Hearing her cries, her "cronies" (tovarki ) came running to her aid, beating the physician and demanding to know whether he would be "torturing us for a long time." When an assistant came to help him, the women attacked him as well. Only when the local police arrived was order restored.[96]

In 1904, the police chief from the city of Narva informed the St. Petersburg provincial governor that a prostitute named Anna Miule had been thrown out of the district hospital for "her scandals and swearing" before she had been cured of her venereal disease. A concerned policeman returned her to the hospital, but the doctor refused to admit her in light of her bad behavior. He accused Miule of using foul language, provoking scenes, and threatening to break all the windows. His answer was for her to receive medical attention where prostitutes were formerly treated—in the local jail. The police chief declined and, instead, had her sent to the hospital in the nearby town of Iamburg. It, however, was full. Asked Narva's police chief, what was to be done?[97]

Prostitutes also fought among themselves. Troubled by frequent disturbances among resident prostitutes, the district hospital administration in Voronezh in 1896 affirmed the necessity of separating them from the rest of the venereal patients. "Brawls among the so-called 'spirited whores' [veselyia devitsy ]" were "commonplace events" in the hospital. The report characterized the prostitutes as having "lost their shame, conscience. proper pity, and love of humanity." They created "so much noise and hubbub with their quarrels, fights, and vile pranks, that they

[95] The 1897 incident was described in Vrach, no. 28 (1897): 794; Kamsko-volzhskii krai, no. 458 (July 1, 1897): 3. The second incident was described in Vrach, no. 43 (1899): 1282.

[96] Vrach, no. 28 (1898): 841; Priazovskii krai, no. 150 (June 1898): 3. In 1900, a Siberian daily reported that ten prostitutes in a Tomsk hospital had gotten drunk on vodka and created a row that necessitated police intervention. Sibirskii vestnik (November 9, 1900), cited in Vrach, no. 48 (1900): 1477.

[97] The provincial governor supported the Narva physician's refusal to readmit her. TsGALO, Vrachebnoe otdelenie S.-Peterburgskago gubernskago pravleniia, f. 255, op. I, d. 852, letter from Narva police chief of July 12, 1904; letter from governor of July 15, 1904.

upset the peace and quiet not only of the first and second women's wards, but even the wards on the lower floor."[98]

We can only guess at the source of such fights. On one hand, they may have originated in personal slights and insults, sexual jealousies, and other private conflicts. According to Bentovin, brothel prostitutes and odinochki were natural rivals in this setting. Furthermore, prostitutes were acutely conscious of their economic standing and this too could lead to problems. Differences of affluence and status, obvious even among the hospital's standard issue gray gowns, evidently took their toll. The wealthier prostitutes interned in Kalinkin managed to dress up their drab uniforms with fine lingerie, lace, bows, and boots with French heels; in their coarse hospital underwear and hand-sewn skirts, the poorer prostitutes provided a sharp contrast.[99]

On the other hand, observers acknowledged that boredom, exacerbated by crowding and physical discomfort, also played a significant role in provoking hospital brawls.[100] Participants at the 1897 congress on syphilis voted that a prostitute's incarceration should not be spent "in idleness or yearning about their interrupted profession." One of their proffered solutions involved seeing to inmates' "moral ascendancy through expedient labor according to each one's taste." This entailed "readings, visits to church, and various distractions."[101]

Though lack of funding and volunteers made it difficult to see such intentions through, several hospitals did implement programs designed to edify and divert their resident prostitutes. An inmate in Kalinkin asked the medical assistant (fel'dsheritsa ), Tat'iana Baar, a "big favor"—"whether you have some kind of work for Mania and me, or some kind of book to look at." With the support of the countess Elizaveta Musin-Pushkina and Tarnovskii's protegée, Dr. Zinaida El'tsina, Baar launched a program whereby inmates could earn money by sewing hospital gowns. In 1897, Kalinkin's resident charitable society provided more than 150 books and journals to the hospital and sent a priest to the prostitutes' ward to read aloud from moral and religious selections. According to the society's annual report, the women listened "with thrilled interest."[102] In Nizhnii Novgorod, occasional shadow plays with a

[98] Meditsinskaia beseda, no. 1 (January 1898): 29–30.

[99] Bentovin, "Torguiushchiia telom," pp. 81–82.

[100] British prostitutes interned under the Contagious Diseases Acts responded to boredom in the same way. Walkowitz, Prostitution and Victorian Society, p. 224.

[101] "Protokoly obshchikh zasedanii," p. xx.

[102] Boris Bentovin, "Spasenie 'padshikh' i khuliganstvo (iz ocherkov sovremennoi prostitutsii)," Obrazovanie, nos. 11–12 (1905): 341–42; Otchet o deiatel'nosti blagotvoritel'nago obshchestva pri S.-Peterburgskoi Kalinkinskoi bol'nitse (St. Petersburg: October 13, 1897–October 23, 1898), p. 4; (October 23, 1898–October 23, 1899), p. 5.