San Miguel

pre-1628; 1693–1710

As a member of the family of New Mexican churches, the chapel of San Miguel is an anomaly in several respects. Its primary congregation was neither the Europeans of Santa Fe nor the Pueblo Indians, but the Indian servants who accompanied the Spanish as they pushed colonization and Christianization north into New Mexico. As a physical form the church today is unique, being capped by a single tower in contrast to the more typical flat-faced and twin-tower arrangements. Only in its interior arrangement does the chapel follow the common mold characterized by a single nave, tapered sanctuary, transverse clerestory, and choir loft.

The first mention of the ermita of San Miguel appeared in a document dated July 28, 1628, in which Governor Felipe de Sotelo Ossorio was charged with "impious conduct during the mass."[1] Hence by that date a chapel already existed, constructed sometime after the provincial capital was transferred to Santa Fe south from San Gabriel in 1610. The site for the chapel lay on the opposite bank of the Santa Fe River apart from the formally planned and plotted part of Santa Fe. The Barrio Analco, as the district was known, was a piece of land settled by the Indians who had accompanied the Spanish as allies and intermediaries. The site shows signs of Indian occupation from the fourteenth century, as evidenced by remains found during excavations under the chapel in 1955 by Stanley Stubbs and Bruce Ellis.[2]

Tradition has it (although without documentary evidence) that a portion of the barrio's residents were Tlascalan Indians from Mexico who had been granted special dispensation by the king because they had allied with the forces of Hernán Cortés in the Spanish battles against the powerful Mezo-American tribes. As a result, they were exempted from paying certain taxes and were allowed to bear European arms. The Spanish also used them as colonial liaisons: to undertake negotiations on behalf of the Europeans and to set an example in farming and mining techniques. They worked, Marc Simmons noted, as colonists, miners, soldiers, and assistants to Spanish explorers and missionaries going north.[3] Although the Pueblos conformed more closely to the Spanish concept of civilization and thus had less need of models, some Tlascalan Indians might have accompanied Oñate's expeditionary forces in 1598. It is believed that at least one Franciscan in the party brought with him a Tlascalan assistant.[4]

Although relatively highly regarded by the Spanish, these Indians were not considered as equals and worked as menial help for the Spanish settlers of

2–1

San Miguel

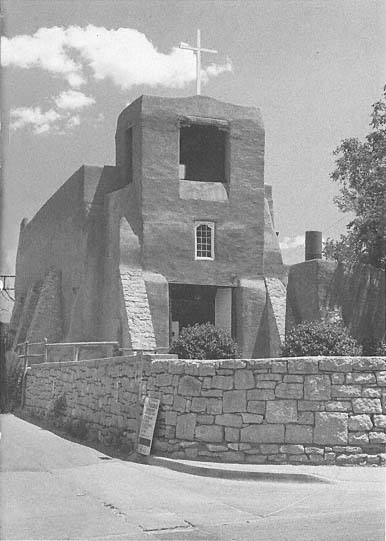

The church in its current form, a curious mixture of stone buttresses,

a single tower, and an oversized void.

[1984]

2–2

San Miguel

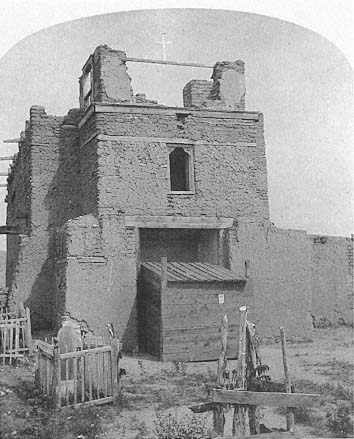

1872–1873

Late in the nineteenth century the five-level tower grew from a solid

earthen base.

[Timothy O'Sullivan, Museum of New Mexico]

Santa Fe. Consequently they settled the land analco , a Nahuatl (language of the Tlascalans) word meaning "across the water" or "on the other side of the river." Whether the barrio's original inhabitants were specifically Tlascalan or were simply other peoples from Mexico has been the subject of some debate. In either case, by 1640 the Barrio Analco was considered a viable community by the Spanish, as evidenced by a document in the General Archives of the Indies. Benavides wrote that "it [the villa] lacked the principal thing, which was the church; that which they had being a poor 'jacal'; because the Friars first gave their attention to building churches for the Indians whom they converted, and among whom they lived and labored; and therefore as soon as I became Custodian, I began to construct the church and convento to the honor and glory of God."[5] One may infer from this statement that the ermita de San Miguel was the first religious structure constructed by the Spanish in Santa Fe, a rather curious occurrence considering the attention given to the formal planning of the town. The construction of the first parroquia followed the completion of the Indian chapel across the river. The 1628 document that cited the governor's misconduct indicated that the Spanish were still using the chapel as their parish church through the late 1620s and early 1630s.

Little is known of the first edifice that occupied the site. Excavations in 1955 by Bruce Ellis and Stanley Stubbs revealed several layers of construction beneath the floor of the current church. The older chapel, believed to have been built sometime before the Reconquest and possibly before the pre-1640 church, was smaller than the present-day building, with a narrow, rectangular apse in place of the current angled walls and a sanctuary raised two steps above the nave. The facade was probably planar, with neither towers nor buttresses.

Relations among the civil authorities, the military, and the clergy were frequently stormy, and in the late 1630s, with the governorship of Luis de Rosas, the trouble was brought to a head. Attempts to resolve the problems had been in vain. When Fray Bartolomé Romero and Fray Francisco Núñez were sent to Santa Fe in 1640 to meet with the governor and attempt a reconciliation, he verbally abused them, beat them with a stick, and had them imprisoned. The friars were later released, but the church was closed and its bells removed.

The culmination of the disputes between church and state was the razing of San Miguel in 1640, the adobes presumably taken down with the vigas and reused in other construction. The drama did not end with demolition, however. Late one night Ni-

2–3

San Miguel

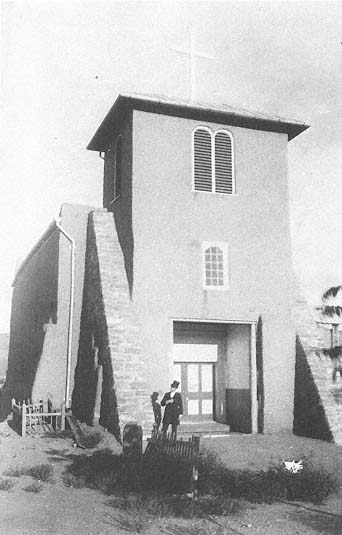

circa 1880

The chapel in derelict condition, the upper stages of its stepped

tower had vanished. Note the embedded timber used to reinforce

the adobe construction.

[F. A. Nims, Museum of New Mexico]

2–4

San Miguel

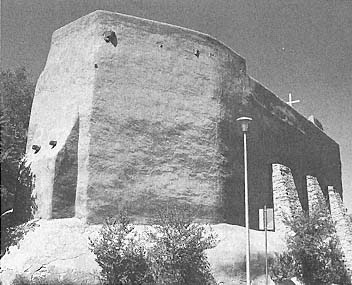

circa 1884

A single, more massive tower has replaced its staged predecessor;

stone buttresses strengthen the facade.

[Dana B. Chase, Museum of New Mexico]

colás Ortiz discovered his wife in Governor Rosas' house, which precipitated a turmoil that resulted in the murder of the excommunicated former governor some weeks later. Rosas was absolved of his activities against the religious by a priest named Juan de Vidania, who was arrested later by the Inquisition but escaped while en route to Mexico. This complex, fascinating, and bizarre chapter in New Mexican history brought into high contrast the chronic antagonisms within the civil administration and the church as well as those between church and state.[6]

Although the church was subsequently reconstructed, the new structure did not last long. Burned during the Pueblo Revolt in 1680, its shell remained unused for the next twelve years. The report issued by Diego de Vargas on his return to Santa Fe made no mention of a need for new wall materials, so it is assumed that only the wooden superstructure required replacement. Vargas, on inspecting the burned church, instructed the people "to roof said walls and to whitewash and repair its skylight in a manner that shall be the quickest, easiest, briefest and least laborious to said natives."[7] In December 1693 men went to the mountains to cut vigas but turned back after several days because of the extreme cold.

The poor condition of the chapel must have upset some members of the congregation, not the least or least noble of whom was Alférez (which corresponds to second lieutenant) Agustín Flores Vergara. In a request to the custos, Flores wrote, "I beseech and entreat his reverence to grant me permission to go about in this city and in other territories of this kingdom, with the holy image, to make a collection of alms which will be of assistance in the execution of the chapel, in order to locate the image therein."[8] He presented this to the custodian, who, Kubler told us, "instantly grant[ed] his request." The history of San Miguel from that time on, at least in terms of politics and ownership, was much calmer.

The repair or major renovation of San Miguel is discussed in great detail in George Kubler's Rebuilding of the Chapel of San Miguel . Ensign Flores had raised the funds for the repairs and had hired fifteen workers to execute the work, although none seems to have been Indian.[9] By calculating the number of adobes needed to repair the walls, Kubler figured their height at about seven feet, although archaeological investigations in 1955 were unable to ascertain whether this estimate was correct. It is believed that the change from the rectangular to angled apse dates from this period, as do the two niches in the

2–5

San Miguel

circa 1881

The apse end of the structure eroded, its mud plaster covering all but

gone, the church's adobes are clearly visible.

Note also the crenellated top courses.

[Museum of New Mexico]

rear wall of the apse currently covered by the reredos. Because no Indian names appeared on the register of workers, there might have been two periods of repair: the first a more cursory effort following Vargas's instructions to get the church back in shape for consecration and the second, carried out in 1710, to glorify its body and raise its aesthetic level. By the end of 1710 the work was finished and a new roof was in place.

The carved beam of the choir loft, which was completely remade at the time, read, "The Marquis de la Peñuela erected this building, The Royal Ensign [sic ] Don Agustín Flores Vergara, his servant. The year 1710."[10] The credit for construction is usually assigned to Vergara, however, Peñuela's name being required by courtesy because he was governor at the time.

Except for the modified form of the apse, the church was probably built on the same foundations and to the same layout as before. What it looked like, however, remains problematic. A work report noted a carpenter's being paid for four small doors "para las torres" (for the towers), although what the towers referred to remains a mystery. Perhaps the plural "towers" could refer to the tapering stepped tower seen in late-nineteenth-century photographs. But in 1776 Domínguez made no reference to such towers. He may have inadvertently omitted mentioning them, and there is some question as to the accuracy of his report, which placed the sacristy on the north side of the church when archaeological evidence shows that it should have been to the south with the remainder of the convento. A tower scheme might have evolved by the mid-eighteenth century, although this, too, is conjectural. Tamarón, in 1760, was more impressed by the spaciousness of the "principal church" and the promise of the "very fine church dedicated to the Most Holy Mother of Light being built." San Miguel received his visit, if not his enthusiasm; "It is fairly decent; at that time they were repairing the roof."[11]

Domínguez also noted that there were only three windows in the chapel, two in the south wall and one in the west lighting the choir loft.[12] Juan Agustín de Morfi observed that the "section of Analco" was in part regular and that most of it was "without order." He mentioned San Miguel only as "a little church . . . where mass is said to them [genízaros] living in the district on feast days."[13] Bishop Juan Bautista de Guevara's 1818 inventory noted a "little adobe tower without bells," hardly the massive construction that accompanies the crenellations visible in photographs from the 1870s. These may date from an 1830 rebuilding under the sponsorship

of Don Simón Delgado or from a slightly later period.[14]

By the time of the American occupation some century and a half after the refounding of the chapel, the nature of the barrio had changed significantly. Some of the Indian residents had followed the Spanish south during the revolt, others had just left, and perhaps others had stayed to merge with the pueblos. Through intermarriage and resettlement, the composition of the district changed, as did the demands placed on the structure. By the mid-nineteenth century only two formal masses each year were being conducted in the church: on St. Michael's Day, May 8, and on September 29.

With annexation to the United States came increased pressure for universal education to the new Anglo way of life, and with Bishop Lamy's prompting, the Brothers of Christian Schools founded Saint Michael's School on the land just south of the chapel. The brothers bought the church from the diocese on July 31, 1881, and used it as a school chapel, holding services on a daily basis. "In this church," wrote Bourke in 1881, "are paintings hundreds of years old, black with the dust and decay of time, which were brought from Spain by the early missionaries." He recorded the beam carving that credited the builder of the church, but he could not make out its date. "With a feeling of awe we left a chapel whose walls had re-echoed the prayers of men who perhaps had looked into the faces of Cortés and Montezuma or listened to the gentle teachings of Las Casas."[15]

The chapel suffered additional physical vicissitudes, this time as the result of natural forces. The roof had been a perennial problem and had been replaced or repaired in 1730 and 1760. The fourtiered tower was toppled by either a wind storm, as some say, or the undermining of the lower walls. In 1887 the lower part of the tower, which formed a narthex to the chapel, was stabilized and capped with a neat pitched metal roof. The round arches of the bell loft had a decidedly non–New Mexican flavor, and in general the result of the 1887–1888 reconstruction was to anglicize the entrance to the church. At this time a disparity already existed between the architectural characters of the front and rear portions of the building. To reinforce the lower walls of the tower for structural purposes, stone buttresses flanked the entrance. Three similar buttresses on the north wall presumably date from this same period. In 1955, the time of the last restoration, all the elements of the 1887–1888 rebuilding were maintained intact except the stone buttresses on the west facade, which were thickened

2–6

San Miguel

The church seen from its eastern, apse end.

[1981]

and plastered to bond them visually with the front of the church. The pitched roof was removed, and the Victorian wooden louvers, still in place for the 1934 HABS drawings, were eliminated to create a simpler void in the belfry. The improvements were considerable. In 1978 church authorities requested the Santa Fe architectural firm of Johnson-Nestor to prepare a "Historic Structure Report and Master Plan" to include a comprehensive history of the chapel as well as projected schemes for restoration and maintenance.[16]

What is the church like today? From the exterior the chapel of San Miguel still appears somewhat uneasy to any eye that has visited several of the mission churches. Its single tower is unlike any others, and the large void in the belfry displays rather awkward proportions for mud-bearing walls. The flanking buttresses appear too thin for adobe construction, and indeed they are made of stone, although stuccoed to conceal that fact. A comparison to those of San Francisco at Ranchos de Taos makes clear the difference in construction materials. And yet in its clumsiness the church does display considerable charm, particularly in its setting in the Barrio Analco, now a historical district that claims the "Oldest House in the United States" just across the street.[17]

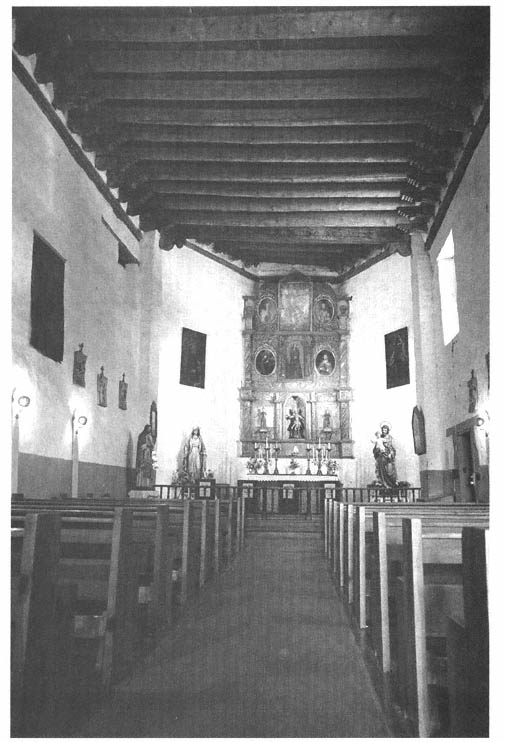

If the exterior is awkward, the church interior appears all the more elegant in comparison. The nave is well proportioned and virtually serene, and with the exception of disturbing recorded messages that play almost incessantly, this is an excellent space in which to consider the history of Spanish architecture in New Mexico. The chapel's shape is classic, with its single nave roughly twenty-four feet wide and seventy feet long and tapering decisively toward the east. The years upon years of replastering have added to the mass of the walls, whose textures indicate the accumulation of time like the steady movement of a clock. In the afternoon when the sun is right, the light sliding through the clerestory is quite striking, evoking a sense of the beauty and drama of light and its role in creating religious presence. With the north windows blocked and the south windows high in their wall, only artificial light detracts from the total effect.

The majority of the vigas, in fact all but two, date from rebuildings in the nineteenth century, and only the two square ceiling beams in the chancel survive from earlier times. The balcony support beams and all the corbels are beautifully carved and lend an air of elegance and polish to the simple interiors. In the course of subsequent renovations, including the work of 1798, the floor was raised two feet with adobe; thus the distinction between the sanctuary and the nave was lessened. In 1853 Bishop Lamy built a stone altar, followed in 1862 by a new communion railing. The wooden floor dates from 1927, and the pews, the most recent addition, were not installed until 1950.

The full-height reredos, which fills the front of the sanctuary, is said to be the oldest in New Mexico. In the center is the small figure of Saint Michael the Archangel. In one hand he holds a sword drawn to conquer Satan; his jeweled crown symbolizes victory. Dating from 1709 and brought from Mexico, the reredos has resided at San Miguel since at least 1776, as evidenced by its inclusion in Domínguez's inventory.

The chapel of San Miguel has had its judgments and suffered its destructions and rebirths. Now protected by law and operated by the Christian Brothers, it is more secure than it has ever been in three hundred–odd years of existence.

2–7

San Miguel

The church interior in the late nineteenth century. Compare the state of the reredos

with its contemporary condition.

[Museum of New Mexico]

2–8

San Miguel, Plan

[Source: Kubler, The Religious Architecture , 1940; and field

observations, 1986]

2–9

San Miguel

The reredos with the figure of San Miguel occupying the central niche.

[1981]

2–10

San Miguel

With its narrow section, heavy vigas, and battered chancel, the nave is a classic representative

of New Mexican colonial religious architecture.

[1981]