From Before to After:

Replicating Late Prehistoric Representation

The top edges of both sides of the Narmer Palette are decorated with frontal heads of bovids, two on each side, possibly depicting one of the cow goddesses, Hathor or Bat, of later mythology (Vandier 1952: 596; see also Baumgartel 1960:91). There is nothing to justify the anachronistic parallel, or indeed the supposition that the bovids are female (although according to the anachronistic interpretation Hathor, as female, should be represented without a beard). It is more consistent with the general narrative metaphorics of the entire palette to take the heads as human-faced bulls. Like the ruler's force "as a lion" on the Battlefield Palette, the ruler's power "as a bull" is figured within the pictorial text: on the obverse bottom, a great bull attacks an enemy's citadel, and on the reverse middle the ruler, smiting his enemy, is depicted wearing a bull's tail in a handle ranging from his belt, decorated also with four bulls' heads—possibly to match the four at the top of the palette—affixed to what appear to be strips of beaded cloth. Although subtle differences among the four heads on the top of the palette have often been remarked, it is unclear how these might be reconstructed in the image as a whole; perhaps they are merely variations in textual morphology that do not bear on the metaphorics. The heads flank a palace facade (serekh ) containing the nar -fish (a species of catfish) and mer -chisel, signs placed also before the largest figure in the obverse top zone, apparently naming the ruler himself. The entire decorated top edge of the palette is sometimes interpreted as depicting a roof or canopy for a facade with bucrania; although not necessary for our purposes, this reading accords with other features of the image.

Below the decorated top edge, set off by a thin register line, the two sides of the palette are divided into three horizontal zones. Except for the "rebus"

(on the reverse top right), each zone on the Narmer Palette containing a representation of the ruler has a register ground line—namely, the obverse top, with the ruler and his retainers inspecting the corpses of ten defeated enemies; the obverse middle, with the ruler's two retainers mastering two serpopards; the obverse bottom, with the ruler-as-bull vanquishing an enemy; and the reverse middle, with the ruler smiting his enemy. By contrast, ground lines do not underscore enemy figures at the obverse top right, the obverse bottom, and the reverse bottom. In each of these zones the enemies are depicted as defeated, twisted on and from their baselines and upright axes, an image presented in another way on the Battlefield Palette. The special place of the enemy on the ruler's ground line in the reverse middle zone will concern us later. The registers therefore mark the different status of figures within the image as being either associated or not associated with the ruler. Thus the Narmer Palette proffers the latest version of the animals' and the hunters' differing grounds on the Hunter's Palette; moreover, as on the Battlefield Palette, the animal enemies of the hunters have become the human enemies of the ruler. In addition to marking and maintaining distinctions indicated in earlier images in the chain of replications, however, the registers on the Narmer Palette divide each zone from the others on that side of the Palette. As elements of composition, passages of visual text, they separate the zones—and thus presumably the elements of the story—in a way that is not presented on the late prehistoric images we have examined so far.

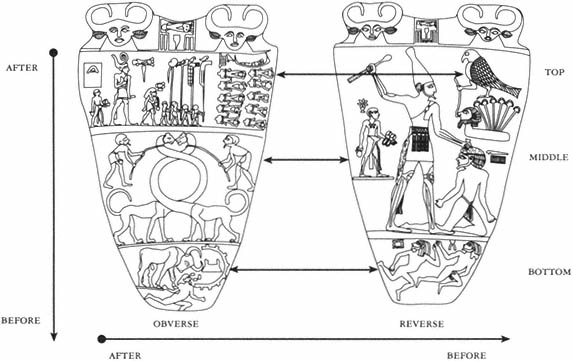

A viewer whose visual culture included the chain of replications of late prehistoric representation would presumably seek to interpret the Narmer Palette in the same way the Oxford, Hunter's, and Battlefield Palettes (Figs. 26, 28, 33) would have been viewed—that is, as a narrative image. Accordingly, on the Narmer Palette (Fig. 39) each side presents a zone depicting what comes after (at the top) and what precedes (at the bottom) the ruler's decisive blow of victory, with the obverse depicting its aftermath and the reverse its preconditions. The story is therefore arranged in the four top and bottom zones of the palette, top-to-bottom/obverse-to-reverse! as consistently after-to-before.[1] The pictorial text, however, also includes elements relating material in the other temporal direction, from before to after (strictly speaking, a counternarrative),

Fig. 39.

The structure of the narrative image on the Narmer Palette.

as well as elements resisting or breaking out of the narrative sequencing altogether. In view of this complexity it is useful to go through the zones one by one before considering their metaphorical and narrative interrelations.

Beginning with the obverse top, the victorious ruler, wearing the Red Crown (it would later signify Lower Egypt, but we cannot necessarily assume this denotation here) and labeled with the two hieroglyphs of his name, is preceded by four standard bearers. He is flanked on the left by his sandal (and seal?) bearer and on the right by a figure most commentators have identified as a "priest" carrying scribal equipment. Carrying the seal's case(?) around his neck and the sandals of the ruler, presumably strapped to his wrist, the sandal bearer is labeled with a rosette and pendant plantlike form. The image on the ruler's seal is apparently depicted above the sandal bearer to the left in the upper left

corner of the zone. Although its status as a seal imprint has not been recognized, the central form in this sign has been tentatively identified as the "reed float" used by Old Kingdom sportsmen to hunt hippopotami (see Baumgartel 1960: 92–93) or the "bilobate Khons sign" (Williams and Logan 1987: 248, note 13); more likely it is a schematic depiction of the ruler's sandals with the strap the sandal bearer uses to carry them around his wrist (see Vandier 1952: 596). The "priest" is labeled with a rope noose or tether and a loaf. There are reasons to suppose that these two personages have special narrative significance; it is even possible to interpret them as members of the ruler's family. The entire group of the ruler and his followers inspect two rows of five decapitated enemies spread on the ground (without ground lines) at right angles to the progress of the victors. The several signs or hieroglyphs placed above this group may or may not be read like later hieroglyphs. One depicts a door on its pivot; it could be taken as the hieroglyph "great door" (= wr -swallow + door; the bird is to the right of the door)—for example, the door of the temple where the palette may have been dedicated or the door of the palace before which the enemies are displayed. Another depicts a falcon, possibly denoting the ruler, carrying or surmounting a harpoon, probably denoting the enemy shown on the reverse of the palette, where he is labeled (with this sign and a sign depicting a pool of water) as "harpoon" or "coming from harpoon territory," presumably a swampy or marshy region. (In both contexts in the pictorial text, the harpoonlike sign is difficult to decipher; the object may be one of the smaller implements—such as bone and ivory pins or hooks—commonly found in predynastic funerary assemblages. For convenience, the label "harpoon" is used here.) A third depicts the "sacred bark" of the ruler. (For possible readings of these signs, see Kaplony 1966; Williams and Logan 1987.) Considering that the obverse top of such images has so far always been constituted as the beginning of the narrative text, the first pictorial text encountered on the Narmer Palette, then, concerns the achievement of the king, the celebration of his victory.

What precedes this episode is related in the top zone on the reverse side of the palette. Here a rebus depicts the enemy or enemies brought to the ruler by a falcon—an aspect, double, or representation of the ruler or perhaps his divine protector. The falcon inserts a hooked cord into an enemy's nose, possibly to

prepare him for the beheading whose aftermath is related in the obverse top zone, where the king inspects decapitated corpses. It is sometimes said that the six stalks of papyrus growing from the enemy's body—treated abstractly and looking like the later hieroglyph for swampy or watered land—signify "six thousand [enemies]," on the basis of a presumed parallel between the papyrus and the lotus hieroglyph (= numeral 1,000), but there seems to be little justification for the equation. Instead, the papyrus may denote the enemy's home territory, Papyrus Land (Vandier 1952: 596). However it should be interpreted, the rebus indicates in a general sense that the ruler—in his aspect as (or with the protection of) Falcon—has defeated his enemies and prepares them for their judgment or destruction.

Continuing the progression backward through the narrative chronology, the scene preceding this one appears on the obverse bottom, where a bull uses its horns to break down the walls of a fortress evidently inhabited by the enemies, one of whom is thrown to the ground, facing away from the bull, and trampled. Like the falcon on the reverse and like the lion on the Battlefield Palette (compare also the bulls on the Louvre Bull Palette, Fig. 37), the bull can be taken as an aspect, double, or representation of the ruler, although he should not be identified with the ruler's human person as such. Within the encircling outer walls of the fortress is a smaller structure with two towerlike sides; it might be equivalent to the sign used to label the right enemy in the reverse bottom zone, which probably depicts a cattle pen or storehouse, but because of its size might indicate the enemy leader's residence. Three small squares in front of the fallen enemy's face and below Bull's horns are difficult to interpret. They may represent fragments of the walls of the fortress broken down by Bull; on the Libyan or Booty Palette (Fig. 53), probably produced as a replication of the Narmer Palette or similar images, they resemble small rectangular houses within the walled towns. This zone seems to depict the moment in the battle when the enemies' defeat was secured. In his aspect as (or with the protection of) Bull, the ruler enters their citadel.

Finally, what comes before this episode is related on the reverse bottom; in the Narmer Palette's sequencing of the episodes of its narrative, the chronological and causal beginning "concludes" the text. Here two enemies are depicted

as fleeing toward the right, that is (returning through the text to the preceding stage, on the obverse bottom), toward the citadel in which they will take refuge to no avail. They look back over their shoulders as if being pursued by the ruler. Although the ruler does not appear in the pictorial text of this zone of the image, the larger text is clear about his presence; the viewer already knows (having seen the obverse bottom) that Bull will break down the enemies' citadel, a building the text had depicted as a broken version of the sign here used beside the left enemy figure to label him. Furthermore, the enemies' glances over their shoulders are directed upward to the figure of the ruler smiting his enemy presented immediately above this zone. Although coming last in the image as it would be viewed in the context of existing late prehistoric representation, at the very bottom of the reverse side of the palette, the narrative "begins," then, with the ruler pursuing his enemy.

Almost all commentators agree that the sign for the left enemy on the reverse bottom depicts or denotes a fortress with bastions. Werner Kaiser (1964: 90) took it specifically to name the northern town of Memphis, presumably, at this period in protodynastic history, an enemy of the Upper Egyptian polity in or for which the Narmer Palette is usually thought to have been made. (This latter assumption is based on the fact that the principal figure of the ruler in the image, in the reverse middle zone, wears the White Crown, in later iconography the symbol of Upper Egypt; that the palette was found at Hierakonpolis in Upper Egypt might be taken as supporting evidence, although the context speaks only to the final deposit of the palette and not to its manufacture and use.) The sign for the right enemy was interpreted by Yigael Yadin (1955) as depicting a "desert kite," a fortified enclosure used by much later desert herders in Transjordan to protect their flocks. (While kites might have existed in prehistoric times, there is no archaeological evidence for them [see Ward 1969: 209]; more likely the structure had a more all-purpose status as a farm building or storage house.) Yadin's reading led him to see the enemies on the Narmer Palette as Western Asiatics and the entire palette as documenting an Egyptian invasion of southern Canaan-an interpretation that could be sustained even if we reject his reading of the sign. (Alternatively, Kaiser read the sign for the right enemy tentatively as denoting the delta town of Saïs, presumably a twin

of "Fortress," or Memphis, in its struggle with Upper Egypt; other readings have also been proposed [see Kaplony 1966: 159, note 190]. It could be a depiction of the knotting of the loincloth worn by the enemy in the reverse middle zone.) If all three signs labeling the enemies on the Narmer Palette, in the obverse and reverse bottom zones, refer to their actual hometowns, then, in Kaiser's (1964) view, the palette could document a contest between Narmer of Upper Egypt and an eastern delta coalition in which the principal enemy, Buto, or the "harpoon" enemy on the reverse middle (Newberry 1908; Vandier 1952: 596; Kaiser 1964: 90), was assisted by Memphis and Saïs.

But I question the wisdom of forcing the Narmer Palette into serving as a document for actual historical events, and of "reading" its images and signs chiefly on the basis of anachronistic parallels with the meanings of particular hieroglyphs in Middle Egyptian script, in order to reconstruct it as an annalistic or commemorative "statement," somewhat like later kings' chronicles, of Narmer's victory. (Some of the signs on the palette have parallels in Archaic Egyptian script, but the denotations of many of these signs are not definitively known and they largely postdate the Narmer Palette. "Reading" the Narmer Palette's signs as hieroglyphs could be greatly elaborated; only a small selection of the possibilities have been noted here.) In some cases the signs certainly have replications in hieroglyphic script, which could be seen precisely as evolving from late prehistoric pictorial narrativity as it is replicated and revised on the Narmer Palette; the palette is complex precisely because it can sustain interpretation in terms of both late prehistoric image making and later canonical representation. But historical method dictates that we interpret it according to the former, the conditions of legibility apparently assumed or accepted by its original maker and viewers, rather than the latter, a mode of intelligibility not completely constructed until the Third Dynasty at the earliest, a full two hundred years later. Moreover, neither a "decipherment" of some of the images and signs on the Narmer Palette as (later) hieroglyphs nor an interpretation of the image as documenting historical events can, in itself, allow us to grasp the scene of representation in which this ostensibly annalistic and documentary statement was produced.[2] For example, even if specific references for the image were found in actual events, they alone could not explain their representation

metaphorically or narratively in the image as such; the scene contains much more than the literal denotation—whether depictive or hieroglyphic—of individual figures, motifs, and signs. For example, to represent or recount the contest and defeat of the enemies, the maker of the Narmer Palette replicated a motif, the ruler "smiting," that had been produced in other historical contexts of replication presumably different from the context of the "wars of unification" and well before even the most preliminary formation of script—namely, the conflict scene depicted in the Decorated Tomb painting at Hierakonpolis (Fig. 5) some 250 years earlier than the palette. Again, in deciding to use Bull to stand for the ruler, the maker was influenced in the chain of replications by earlier or other representations of the ruler in the aspect of a great animal. His choices in replicating the existing metaphorics of "looking backward" date to the Oxford Palette at least. In all these cases the meaning of figures, motifs, and signs on the Narmer Palette must have derived, in context, from this earlier history of signification; an appeal to the later meaning of the images—in hieroglyphic script or canonical art—besides being unnecessary, is likely to ignore the inherent structure of disjunction in the replication of symbol systems.

For the moment, then, it is best to leave open the question of the specific denotation of the signs labeling the enemies; we can take them as generic labels for a "harpoon" enemy and two others, "fortress" enemy and "desert-kite" (or "knot") enemy, all of which could have had a symbolic or metaphorical as well as a literal significance for contemporary viewers. Whether the ruler, in his battle with "Harpoon," "Fortress," and "Desert Kite," is conquering new territory, suppressing a revolt, or carrying out some other action is difficult to determine (although many commentators would take the image to denote the territorial expansion of the Upper Egyptian polity, whether to the north or to the south, in the so-called unification of Egypt). The pictorial mechanics of the image—independent of any "meaning," probably irretrievable, it might have had for certain viewers—probably require only that the ruler's activity be construed as a victory with certain particular symbolic features. In fact, it was precisely because a metaphorical and narrative system of representation had evolved in the chain of replications of late prehistoric image making that any

particular activity of any individual ruler could be rendered intelligible to viewers. Whether or not episodes of actual conflict that had taken place or were taking place at the time the image was made sustained interest in the replication, the visual text could be replicated in later image making with or without reference to the "real" denotanda of any particular, individual replicatory version. (For the continued replication of the "smiting" motif in canonical image making, see Davis 1989: 64–68; Hall 1989.)