Palace Hotels

After the Civil War, new hotels—some of them with only middle-income dining and service—jumped to a size of 500 and 700 rooms. By the 1880s, dozens of hotels in any large city could boast "first-class" amenities; the term had come to mean merely a good hotel rather than a socially exclusive hostelry. To distinguish the one to five most elite hotels in the region, citizens began to speak of palace hotels—hostelries that maintained the pinnacles of price, luxury, fine food, social prominence, and architectural landmark status.[34] The heyday of residential life in palace hotels occurred between 1880 and 1945. In name as well as in experience, the Palace Hotel of San Francisco exemplified the type for the Victorian era. The $5 million hotel opened in 1875 and covered an entire city block. Its two prominent owners—the state's most audacious capitalist and a wealthy U.S. senator—set its social status. It had 755 rooms in seven stories arranged around a large central courtyard with a skylight and two additional very large air wells. For the next thirty years, the Palace reigned as a landmark. Its massive seven-story volume loomed over the city, and its hundreds of bay windows dominated downtown vistas (fig. 2.8).[35]

The sumptuousness of a palace hotel suite was recorded in 1879, when Sala enthusiastically listed the furnishings of his $4-a-day "alcove bedroom" at the 400-room Grand Pacific in Chicago:

Height at least 15 feet; two immense plate-glass windows; beautifully frescoed ceiling; couch, easy chairs, rocking chairs, foot stools in profusion, covered with crimson velvet; large writing table for gentlemen, pretty escritoire for lady; two towering cheval glasses; handsomely carved wardrobe and dressing table; commanding pier-glass over mantelpiece; adjoining bath-room beautifully fitted; rich carpet; and finally the bed, in a deep alcove, impenetrably screened from the visitor's gaze by elegant lace curtains.[36]

Sala concluded that there was no more splendid hotel in the world than the Grand, although he said something similar about almost every pal-

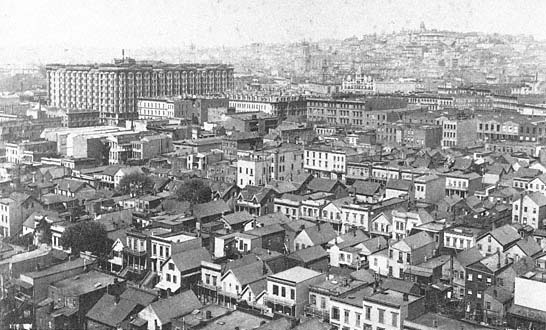

Figure 2.8

San Francisco's Palace Hotel, as seen from the South of Market district, ca. 1890. The hotel, at rear left,

was a Victorian era landmark in every sense of the term.

ace hotel he visited. From 1820 through the 1940s, suites of two or more rooms remained part of the standard plan of all large hotels. Many were typically occupied by permanent guests.[37]

The elegance, comfort, and convenience of palace hotel life relied not only on food and architecture but also on the level of human and mechanical service. Like ocean liners, some palace hotels employed as many as four or five staff for each guest; ratios of one employee to one guest, or three to two, were the minimum for a palace hotel. In 1990, the twenty to thirty most expensive hotels in the United States were still distinguished by lavish hospitality and an extremely high level of personalized service.[38] Only a small fraction of the hotel personnel were publicly visible as clerks, bellboys, elevator operators, or waitresses. The rest worked in what Sinclair Lewis called (in 1935) "the world behind the green baize doors at the ends of the corridors." There one found industrial-scale machinery that could heat and air-condition thousands of rooms, provide instant hot water, and launder thousands of napkins and sheets. There were large shops for upholsterers, carpenters, and plumbers, along with tailors, printers, florists, and a dozen other trades and specialties.[39] Indeed, in any period after 1880, the gen-

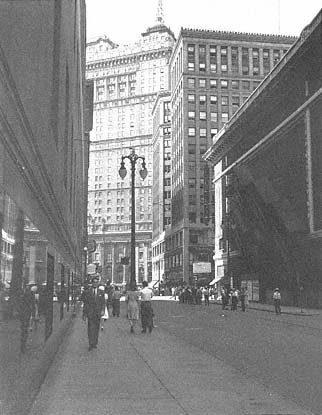

Figure 2.9

Palace hotel as landmark: the Book Cadillac Hotel in

downtown Detroit. Photographed in 1942.

eral manager of a palace hotel hired, trained, and supervised a staff of thousands. At peak seasons and for special events, the manager routinely employed by the day hundreds of additional helpers.

In 1893, when the owners joined the 10-story Waldorf Hotel and its adjoining 16-story Astoria Hotel to create the original Waldorf-Astoria, they set a 1,000-room pace for the new post-Victorian generation of palace hotels. In 1907, the 18-story Plaza Hotel at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Central Park South easily surpassed the Waldorf-Astoria as New York's leading palace hotel.[40] In the next fifteen years, palace hotels elsewhere—for instance, the Book Cadillac in Detroit and the 500-room Drake Hotel on Chicago's Lake Shore Drive—set sparer architectural styles but changed little else (fig. 2.9). On the upper floors of such hotels a few wealthy families often built 10- to 30-room penthouse suites. A case in point is a 1913 hotel home built by a shipping and lumber baron at the top of San Francisco's St. Francis Hotel. He leased two entire floors, one for his family and one for the servants. The

entertaining rooms of the family's suite survive today as part of San Francisco's City Club.

Builders of the next generation of palace hotels, beginning in the mid-1920s, added parking garages and true skyscraper towers but offered smaller guest rooms. Hotels like San Francisco's Sir Francis Drake prominently advertised their built-in garage, with elevator service direct from the garage to guest room floors. The typical bedrooms in late Victorian palace hotels had been 20 feet by 20 feet, offering twice the floor area of rooms in fine hotels built in the 1920s. The palace hotel rooms of the 1920s were still elegantly furnished—but no longer with brocades, fringes, and ornamental brass.[41] Outside, a tower of 18 to 30 stories, in Art Deco architectural style, was almost essential. Managers experimented with penthouse dining rooms; with the end of Prohibition, they added flamboyant bars to the tops of their hotels. Radio stations or at least radio programs originating in palace hotels became another way for hotels to retain their prominence.[42] In 1930, the new Waldorf-Astoria leapfrogged the Plaza in size but never regained its social hegemony because the Waldorf was simply too large. Three hundred of the new 2,253 guest rooms had parlors, but true palace hotel status accrued only to the Waldorf Towers section, which had its own entrance and 500 deluxe suites with 18-foot ceilings, open fireplaces, 45-foot by 25-foot drawing rooms, and 14-foot by 18-foot bath-dressing rooms. In the 1980s, rents for such a suite could range from $5,000 to $8,000 a month. The Waldorf Towers attracted many world-famous people as residents, including Herbert Hoover (who lived there from 1934 to 1964), General Douglas MacArthur (1951 – 1964), Henry Kissinger, and former President Gerald Ford.[43]

Permanent residents retained a prominent part in palace hotels up to the early 1960s, and some palace hotels still had permanent residents in 1990.[44] A San Francisco journalist's survey in 1983 found fifteen residents, including Cyril Magnin at the Mark Hopkins, living in three of the city's palace hotels, still echoing the advantages listed by generations of palace hotel dwellers. Ruth Fennimore, at ninety-one years of age, had worked hard to return to hotel life. She and her husband had lived in a palace hotel for a year after their marriage in 1912. In 1973, some time after her husband died (he had been a prominent optician and president of the Retail Merchants Association), Mrs. Fennimore moved back into a hotel. For her one-bedroom apartment, the rent was

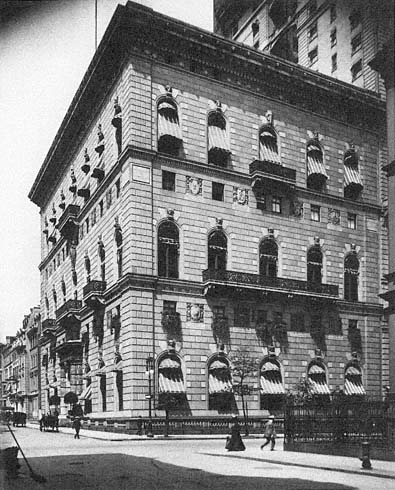

Figure 2.10

The University Club in New York. A classic example of an elite

residential club, it contrasts sharply with the houses to the left.

more than $3,000 a month, but that included what she called "perfected service." She and the other residents visited back and forth just as suburban neighbors did. Another resident confessed, "You know, when you're 86, most of your friends are in the cemetery. The Huntington is my family, from the lowest housekeeper to the manager."[45] San Francisco's permanent palace hotel residents were mostly elderly, although the families of three corporation presidents also kept suites at the Huntington. In other cities, hotel life at the palace level has depended more on the whim of hotel managers than on the demand; only a few managers are willing to take permanent residents. New York City remains the capital of palace hotel living.

If single men or single women were of upper-class social status but did not want to live the relatively public life of a palace hotel, they

might have chosen life in an elite private club (fig. 2.10). Each city had its own top clubs, but usually an expensive club's exclusivity, its quiet and dignified buildings, reasonably good food, and social contacts made residence there a substitute for palace hotel life. For many, clubs were an improvement on hotel life. Because club members carefully chose their companions, life in a club was guaranteed to be more exclusive than life in a hotel, which accepted almost anyone who could pay. Living at a private club was also a prime option for elderly men and women of high status but lowered spending capacity, since living in elite clubs could often cost less than living in posh commercial hostelries.