Dances of Vice, Horror, and Ecstasy

In 1922, Berber and Droste published (in Vienna) a strange book of poems, photographs, drawings, and semitheoretical statements (by Leopold Wolfgang Rochowanski [1885–1961], a Viennese cultural historian, expressionist poet, and promoter of radical expressionist art and dance) related to the

[3] Henri tried to establish himself as a dancer in New York in 1929–1930 but was not successful because, apparently, he was "so persistent in strangling his own potentialities for the sake of an ideal only visible to himself and a little group of similarly attuned spirits" (The Dance, 14/1, August 1930, 60). By far the most complete account of Berber's life and art is Jencik, Anita Berberova (1930). Fischer's Anita Berber (1984) does not examine her dancing with any specificity, nor does Leo Lania, Der Tanz ins Dunkel: Anita Berber (1929), both of which concentrate on the sensational aspects of her messy life. That is also the case with Rosa von Praunheim's sleazy 1987 film Anita Berber—Tänze des Lasters und des Grauens, a campy story about an old woman who imagines that she is Anita Berber. In Amsterdam in March 1990, Ute Dörner choreographed and danced in a piece called Tanz ins Dunkel about Berber's life with Droste. An even more outrageous desecration of Berber occurred in San Francisco in March 1994, when Mel Gordon, in collaboration with the Goethe Institute and punk rock singer Nina Hagen, staged The Seven Dances of Lust, a garish, absurdly "decadent" bio-drama at Bimbo's 365 nightclub.

Die Tänze des Lasters, des Grauens und der Ekstase, which they had performed in Berlin (Figure 26). Fischer claims the couple made a film of the same title in Vienna in 1923, but if so it has disappeared. The relation between the poems and particular dances is not clear from either the book or descriptions of the performances. Berber and Droste staged dances bearing the titles of the poems; it is not known if anyone spoke the poems before or during the performances, but the structure of the dances apparently corresponded to the "voice" of the poems. Berber's writing style differed from Droste's in that she linked words together to represent, rather conventionally, the rhythms of sensory perception that form a complex image in the mind, as these lines from "Orchids" indicate:

For me they [orchids] are like women and boys—

I kissed and tasted each until the end

All all died on my red lips

Droste, by contrast, isolated words and phrases so that they called attention to themselves as discrete energies that did not depend on an action (a verb) to establish intense emotional relations to each other, as appears evident in "Kokain" (Berber was a cocaine addict):

Walls

Table

Shadows and cats

Green eyes

Many eyes

Millionfold eyes

The woman

Nervous scattered cravings

Inflamed life

Swollen lamps

Dancing shadow

Little shadow

Great shadow

THE SHADOW

Oh—the leap over the shadow

It tortures [me] this shadow

It martyrs [me] this shadow

It devours me this shadow

What desires this shadow

Cocain

Outcry

Animals

Blood

Alcohol

Pains

Many pains

And the eyes

The animals

The mice

The light

These shadows

These terrible great black shadows

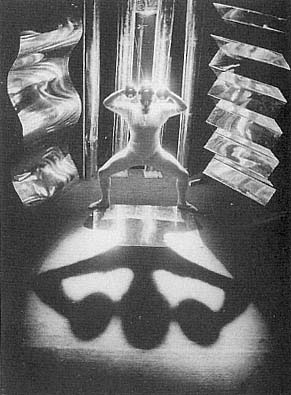

According to Jencik ("Kokain"), Berber interpreted this poem as a dance with the aid of some unidentified piano music by Saint-Säens and ominous scenery by Harry Täuber featuring a tall lamp on a low, cloth-covered table. This lamp was an expressionist sculpture with an ambiguous form that one could read as a sign of the phallus, an abstraction of the female dancer's body, or a monumental image of a syringe, for a long, shiny needle protruded from the top of it. Light emanated from a beacon in the middle of the sculpture and allowed the dancer to cast a powerful shadow, requiring her to perform movements that made the motion of the shadow as interesting as the motion of her body. It is not clear how nude Berber was when she performed the dance. Jencik, writing in 1929, flatly stated that she was nude, but the famous Viennese photographer Madame D'Ora (Dora Kalmus) took a picture entitled "Kokain" (included in the book) in which Berber appears in a long black dress that exposes her breasts and whose lacing, up the front, reveals her flesh to below her navel. Because Berber performed other dances in the nude, and because nudity in dance is a persistent theme of the book, it is possible that Berber sometimes performed Kokain completely nude and sometimes performed it wearing her costume, depending perhaps on the moral climate wherein the performance occurred.

In any case, according to Jencik, she displayed "a simple technique of natural steps and unforced poses." But though the technique was simple, the dance itself, one of Berber's most successful creations, was apparently quite complex. Rising from an initial condition of paralysis on the floor (or possibly from the table, as indicated by Täuber's scenographic notes), she adopted a primal movement involving a slow, sculptured turning of her body, a kind of slow-motion effect. The turning represented the unraveling of a "knot of flesh." But as the body uncoiled, it convulsed into "separate parts," producing a variety of rhythms within itself. Berber used all parts of her body to construct a "tragic" conflict between the healthy body and the poisoned body: she made distinct rhythms out of the movement of her muscles; she used "unexpected counter-movements" of her head to create an anguished sense of balance; her "porcelain-colored arms" made hypnotic, pendulumlike movements, like a marionette's; within the primal turning of her body, there appeared contradictory turns of her wrists, torso, ankles; the rhythm of her breathing fluctuated with dramatic effect; her intense dark

eyes followed yet another, slower rhythm; and she introduced the "most refined nuances of agility" in making spasms of sensation ripple through her fingers, nostrils, and lips. Yet, despite all this complexity, she was not afraid of seeming "ridiculous" or "painfully swollen." The dance concluded when the convulsed dancer attempted to cry out (with the "blood-red opening of the mouth") and could not. The dancer then hurled herself to the floor and assumed a pose of motionless, drugged sleep. Berber's dance dramatized the intense ambiguity involved in linking the ecstatic liberation of the body to nudity and rhythmic consciousness. The dance tied ecstatic experience to an encounter with vice (addiction) and horror (acute awareness of death).

Movement toward ecstasy (and utopia) entails the convulsion or fragmentation of the body and (as the form of the poem implies) language. The ecstatic body vibrates with multiple rhythms. But an acute sense of rhythm is simultaneously an acute sense of time arising out of an acute intimation of death, of finality, of stillness and silence. The dancer's ecstatic rhythm is in fact a struggle to transcend rhythm itself: ecstasy is an anesthetic state, a condition of being drugged, free of bonding emotions. Rhythm signifies not liberation but repetition, addiction, craving for balance in a world of shadows; it is the mechanization of time and feeling, that which makes of the body a marionette. Thus, mechanization does not exist in tension with ecstatic experience; it is the drive toward ecstasy. It is the aesthetic correlate of addiction, of dependency on surrogate sources of pleasure (drugs, music). And, just as ecstasy is within vice and horror, so the healthy body is within the poisoned body. The nude body is the site of contradictory rhythms, of conflict between drugged and erotic drives toward ecstasy. But the healthy body can triumph over the poisoned one only through the voice, speech, language, the cry—which, however, the dancer cannot produce.

Droste's words, the language of the other, the male partner, inspire complex movements but remain unspoken. Missing are the actions (verbs) that define the relation between the identities listed. Dance does not translate the words into movements; rather, it supplies the movements the language motivates. Nudity here signifies a state of heightened aloneness before the shadow-other, before an anonymous audience, before "millionfold eyes," before the "devouring" image of death. The death-suffused words of the (male) other motivate nude dance, which in turn exposes the relation between the body, modernity, and ecstasy. Cocaine is not a source of ecstasy but a sign of modernity; ecstasy entails a performance of the nude body before an anonymous audience, without fear of appearing ridiculous, of disclosing masochistic dependencies on drugs, mechanized rhythms, or men, of the "horror" of narcissism provoked by being the only one naked. Such performance of nudity is in effect a mode of ecstatic confession, an intense

pleasure in showing people how utterly alone and different one is in a modern world of addictions and mechanized rhythms.

Giese, Hagemann, and Menzler implied that the most powerful sign of a unique personality is nude dance. Berber's dance did not contradict this implication, but it was "more naked" than nude dance elsewhere in constructing a perception of uniqueness as a condition of stark aloneness, estrangement, and perversity. Nude dance was no cure for cocaine; it was not modern because it had any therapeutic effect. For Berber, nude dance aestheticized her sickness, and by doing so, by aestheticizing the addictions, compulsions, and mechanized rhythms defining the modern body, her dance anticipated postmodern sensibility; it was an almost satiric critique of the pretentions to a healthy, modern identity that both eurhythmic consciousness and Nacktkultur sought to achieve. Pleasure for the modern audience (not just the dancer) depended on aestheticizing, through nude dance, the symptoms of an incurable aloneness that makes the body modern.

However, the meaning of Kokain should not be detached from the context of its presentation (as a "dance" of vice, horror, and ecstasy) in the strange book Berber and Droste published. It is difficult to imagine, let alone find, a more bizarre and complex relation between dance, writing, speech, nudity, and image than that found in this little book. Berber wrote only four of the twenty-six poems in Tänze des Lasters, des Grauens und der Ekstase, and none of these inspired a dance. Droste wrote all sixteen of the poems the couple danced. He was the solo dancer for four of the poems, and Berber was the solo dancer for another four. The couple danced as a pair for seven of the poems, and one poem, which apparently never reached live performance, required three distinct "persons"—a "murdered woman," a "murdered boy," and a "hanged man"—as well as an "accusatory mob" and a "hundred thousand corpses."

Some poems are quite tiny; others run on for three or four pages. The mood of all the poems is consistently morbid and decadent, with pervasive references to death, phantasmal figures, tortured flesh, narcissistic sensuality, and narcotic visions. Droste juxtaposes allusions to artworks and artists with images of archaic cultures: Byzantium, ancient Egypt, imperial Rome, the sinister world of the Borgias. He also decorates his poems with mention of exotic sensations and materials: gold, diamonds, pearls, amethyst, silver light, perfumes, wax, powdered skin, distant organ tones, glass objects, silken pajamas, lurid lampglow, blue mist: "Woman/Red-haired/Gold net/pearls on the forehead." But the most disturbing references are to bodies (living and dead), parts of bodies, and body metaphors: "fingers like blood," "powdered thighs," "gold on the naked body," "green eyes," "screaming green," "boyish arms," "white head," "flaming hair," "ecstatic hands," "painted like a whore," "glassbright cry," "sibling corpses,"

"yellow-green desires," "the trembling steps of woman," "Oh she is an orchid/And seven heads." All these rhetorical devices construct an image of the dancer, male or female, in which the glamor of the body arises out of its morbidity. It is a variant of Wigman's perception of dance as ecstatic movement toward death.

But in Wigman's case, a different relation between writing and movement prevailed. With Wigman, writing preceded dance in the form of dense notebook collages of words and drawings whose meaning was often indecipherable. For her, dance was a phenomenon that freed the body from inscription, from containment within a text (or supertext). Berber and Droste apparently treated this belief in moving from writing to dance as incomplete, even naive. Though each individual poem may have motivated the dance that bears its title, the calculated aesthetic effect of the book (which extends to the typography and luxurious paper) suggests a more complete movement, from writing to dance back to writing. For these authors, dance performance continued beyond the moment the body made movement synonymous with life. The lurid, seductive book included some documentation of dance performance (as if to convey that documentation allows performance to live on after it is over); more important, it presented itself as a collection of dances, constructing the perception that dance is complete only when dancers become authors and transform their dances into poetic inscriptions. Whereas Wigman saw dance as life that emerges out of writing, Berber and Droste understood dance as an art that emerges out of writing and completes itself through publication in the form of a book. The writing was only one element of a performance that included an assortment of images and codes. For Berber and Droste, the body had to free itself, not from words or images, but from the all-too-brief moment in which it lived through performance. However, the dominant sign of this freedom was not words nor writing as such but rather the perverse book, which attempted to blur distinctions between writing and movement by obscuring relations between poems and dances. One might say, then, that insofar as the book represented a further state of nakedness for the dancer, the desire for nakedness entailed a desire to construct a highly ambiguous rather than ultimate perception of identity.

Consequently, it is almost impossible to determine the extent to which the dances translated into movements the words, syntax, or rhetorical devices of the poems. Theoretical statements by Droste and Rochowanski provide some clarification. These also appear as poems. In "The Dance as Form and Experience," Droste, asserting that "form is the expression of an inner experience" that ballet is incapable of embodying, concluded that the dances he and Berber performed constituted an "unconscious, sacred movement to the sounds/of an alien world" (16). Perhaps, then, the poems

were supposed to project the emotional effect of this alien sound world rather than to encode specific correlations between bodily movements and particular words, syntactic structures, or rhetorical devices. Even so, it is probably impossible to detach the morbid and ecstatic effect of the poems from their referents or semantic values. Indeed, the whole book constituted a fantastic network of referentiality. Poems referred to dances, and dances referred to poems. Both poems and dances referred to both art and the lives of the dancers/authors. In the theoretical (that is, undanced or undanceable) poems, Berber and Droste referred to each other with narcissistic intensity. But all these layers of referentiality became so convoluted that referentiality itself became a sign of morbid doubt over the authenticity of what was written or written about. The incessant, gaudy references to nudity, the body, and the decoration or masking of the body disclosed an inclination to believe that neither nudity nor the body were signs of authentic being; they were signs of fantasy, hallucination, upon which the intersection of horror, vice, and ecstasy were predicated.

Droste developed this perception most overtly in one of his theoretical poems, "Der Lasterhafte und der Nackte" (The Vicious and the Naked), which is actually a violent kind of allegory. In his apartment, a man powders, perfumes, and ornaments his nude body. Having completed this ritual, he dons a cape and visits a bar in a Roman piazza frequented by homosexual boys and prostitutes. He has a drink, leaves without paying, and goes to another lonely piazza, where he removes the cape and stands naked, "smiling at his slender powdered thighs" and apparently masturbating. "A cry went through the streets/Out of the alleys streamed" singing fascists, "slender boy bodies," and frenzied women, all of whom sink to their knees before him, as if he is an idol. "Only the vicious one stood smiling in the crowd." This figure wears a dark coat and dark glasses, but he also powders his face and paints his lips. He approaches the naked one and kisses his navel, frightening away the crowd. The vicious one proceeds to strangle the naked one "with scientific precision," then decapitates him.

Then he took the painted head of the naked one back home

Placed it in a glass baroque vitrine

And sank trembling to his knees

None of these extreme actions involves any speaking (except for the anonymous cry provoked at the moment of the man's disrobing). This poetic language produces a scenario for bodily movements that possess the voiceless authority of a perverse, violent dance. The poem presents nudity as a silent yet public performance that awakens unspeakably turbulent emotions in crowds, classes of persons, and one "vicious" individual. Nudity appears as the obverse condition of viciousness, a monstrous desire to torture and

mutilate that body that puts its nudity on public display. The murderer reduces the naked body to a part, which he fetishizes, a part (the head) that one normally exposes anyway.

Most significant, public nudity here signifies a feminization of the male body, in the sense that powdering, painting, and bejewelling the body are signs of a feminine attitude. The poem suggests that it is not the nude female body but rather the feminization of the nude male body that gives rise to intensely turbulent emotions in public performance. Male nudity is feminized when it becomes an element of an aesthetic performance, of a dance. The act of exposing the genitals, in public and for aesthetic effect, is feminine, regardless of whether the genitals are male or female. For this reason, perhaps, it is very difficult to find examples of total male nudity in German modern dance. Droste sometimes performed in a loincloth (as in his St. Sebastian dance) but never completely nude, as Berber sometimes did.

Despite the shocking effect of this poem, it is the image of Berber's body that dominates the book. Even the body of the male nude in "Der Lasterhafte und der Nackte" impersonates the powdered, orchidaceous body projected by Berber in the other poems/dances. The brief, theoretical poem immediately following "Der Lasterhafte und der Nackte," titled "Versuchung," is "dedicated to Anita" and purports to describe Berber's body. The poet identifies her "slender naked boy thighs," her "slender purple petals," her whiteness, her fullness, her "clouds of powder," with particular actions or movements: the spreading of "countless raptures," the breathing of the wind, the pressing of desires, the quivering of flesh and the clinging of things to it, the veiling of lights, the gleaming of glass, the undulating of tassels, the waving of the arms, the pulling of "immeasurably wide spaces," the entwining and winding of circles. These movements, ascribed to the nude female dancer as a set of events devoid of narrative context, awaken male desire over and over again, in "circle and circle," and create "temptation," which threatens to destroy or corrupt the male body. It is movement performed by the female body, not anything spoken, that tempts the male poet.

But what does it mean for feminine movement to tempt the male poet? Because Droste wrote the great majority of the words in the book, including all the poems made into dances, it would seem that temptation implies a kind of fatal submission to language, an urge to write, to speak, to disclose morbid desires, the exposure of which addictively enslaves him to the one person who understands him, his partner, the female dancer. In spite of the lurid implications for nudity in male aesthetic performance theorized by "Der Lasterhafte und der Nackte," the riskiest, "most naked" manifestation of male vulnerability is apparently not nudity in performance but writing and speech that motivate performance. The relation between language and bodily movement is as symbiotic as the relation between Berber and Droste.

Narrative-free movements of the female body motivate the male body to write, to speak, to inscribe, to narrate the female body as a dance. But in seeking union with the female body through dance, the male body becomes female insofar as it impersonates the feminine signs of the powdered, painted body. At the same time, the female body displays signs of masculinity: "slender naked boy things," "boy arms," a knifelike form. The relation between language and movement is ambiguous, interpenetrating, with the result that neither language nor dance nor nudity can lead to greater authenticity of being . For Wigman, movement constructed authenticity of being, and language (writing) was an initial manifestation of movement. For Berber and Droste, however, modern dance and the language that motivates it undermine secure categories of sexual difference, and in doing so they also expose narrative itself, in language and in dance, as morbid, decadent, a pathological mode of signification. Modernity itself then refers not to any condition of inauthenticity but to consciousness of the idea that the authenticity (and therefore the inauthenticity) of signs is a myth. The pleasure of the modern body derives from the supposition that narrative can no longer contain the body to which it refers, that performance does not contain enough signs to signify the unspeakable aspects of desire and identity.

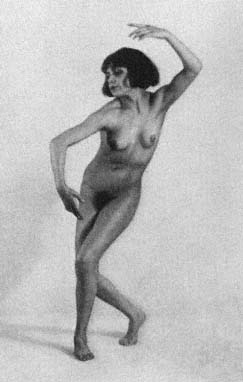

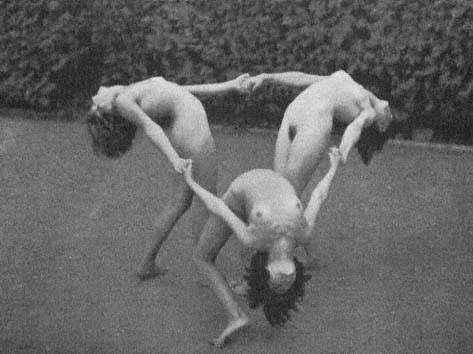

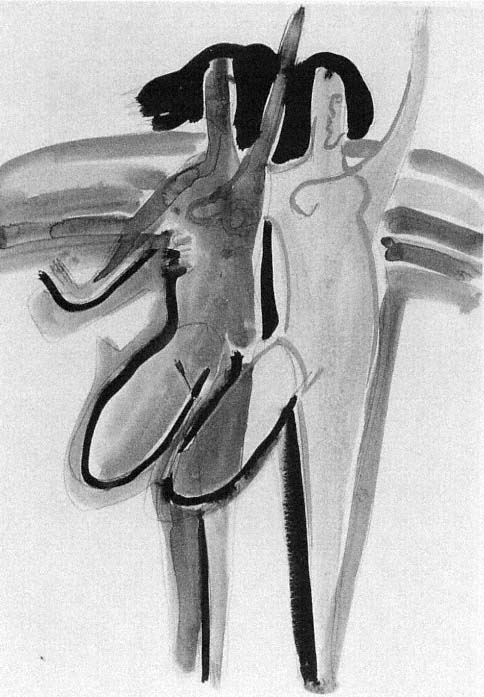

The book amplifies the ambiguity of the relation between language and dance by its use of illustrations. These call attention to the problem of establishing the authenticity of the language that defines the modern body. Droste and Berber present sixteen photos of themselves taken in the Viennese studio of Madame D'Ora. Of these, only five include Droste, and only two feature him alone—the rest are of Berber alone. The photos bear no captions. Though the poses and costumes Berber and Droste adopt are from their dances, the photos are in no sense documentations of their dance performances; rather, the poses give the photos their own lurid, glamorous value. The sequence of pictures constitutes an artwork that shows the female body's capacity to exist independently of either its partner or its "original" performance. Berber undermines the authority of this glamor by including three of her own drawings, grotesque caricatures, of her head alone in profile. In two of them she appears bald-headed and wears outrageously huge earrings on her tiny ears, and in all three her heavily mascared eyelids vanquish any view of her eyes themselves. Yet each profile gives her a different identity: the first (bald-headed with small turban), fantastically Asian; the second (bald-headed with halo), a sort of monk wreathed in cigarette smoke; and the third, a sleek cosmopolitan with short-cropped black hair (she was actually a redhead).

These crude self-portraits give way to performance documentation: seven paintings, in color, by Harry Täuber of scenery and costumes employed in specific dances. These, preceded by Täuber's short prose preface, contain captions briefly describing the actions meant to occur within the contexts

depicted. Here Berber and Droste are neither glamorized nor caricatured but rather are given a tortured, "demonic," expressionistic look. Whereas the photos glamorize the dancers after having performed their dances, the paintings present the images the dancers strove to achieve through performance. These are stark, violent images, saturated with gloomy shadows, glaring light, and distorted perspectives. The small, anguished bodies of the dancers appear imprisoned in monumental spaces of terror and pain. Yet are these images any more authentic than the others?

Berber and Droste preface their book with two more images of themselves, drawings by the Viennese artist Felix Harta (1884–1967), who did many sketches of theatrical personalities. These are done somewhat realistically, with Berber and Droste, facing each other in profile, presented as debonair, even cute, embodiments of brash youth. But the very sketchiness of the drawings suggests a quite incomplete perception of the subjects. Altogether, the illustrations fail to stabilize perception of the author-dancers, reinforcing the governing idea that neither language nor movement nor music nor image nor nudity nor any complete unveiling that allows us to "see everything" has any special power to establish the authenticity of the modern body, to affirm that modernity is a progression toward authenticity of being, or to persuade us that liberation depends on achieving authenticity. Nevertheless, the complicated aesthetic of Anita Berber is as modernist as eurhythmics, Nacktkultur, and Nacktballett in linking modern identity to a more naked condition of being than premodern consciousness ever contemplated. Obviously, being naked in itself is not modern; yet it is difficult to imagine modernity reaching more extreme or controversial expression than through nude dance, than through the desire of a naked body to be seen making purely aesthetic movements that render both desire and the body more naked.

Figure 1.

Dancer at the Ida Herion School in Stuttgart. Photo by Alfred Ohlen,

from Adolphi and Kettmann, Tanzkunst und Kunsttanz (1927).

Figure 2.

Dancer at the Ida Herion School in Stuttgart.

Photo by Paul Isenfels, from Isenfels, Getanzte Harmonien (1926).

Figure 3.

Ursula Falke in a pose from Der Prinz (1925).

Photograph by Richard Luksch (Hamburg),

from Hamburg Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe.

Figure 4.

Karla Grosch performing Metalltanz (1929)

at the Bauhaus experimental theatre

studio in Dessau, from OS, 93.

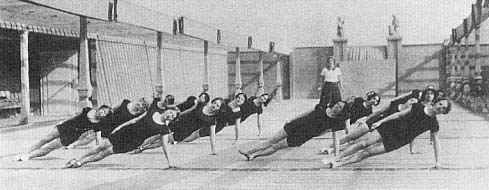

Figure 5.

Open-air rhythmic gymnastic exercises at the Dalcroze school

in Hellerau around 1913. From a contemporary postcard.

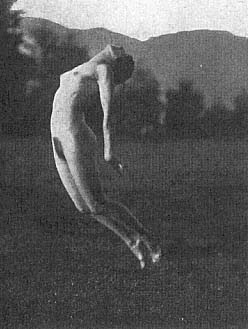

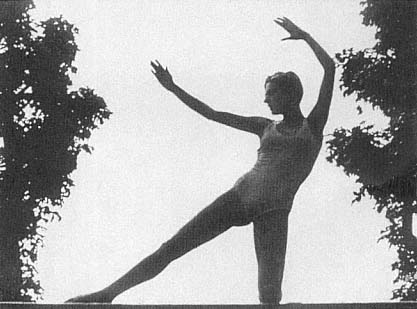

Figure 6.

Gertrud Leistikow performing in a meadow

near Ascona, 1914. From HB, plate 68.

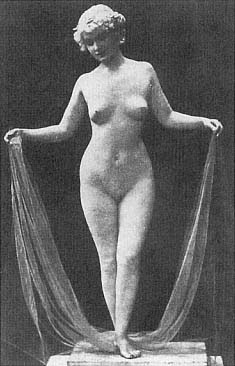

Figure 7.

Olga Desmond in "classical" (sculpted) nude

tableau, Berlin, 1910. From Andritzsky and Rauthenberg,

"Wir sind nackt und nennun uns Du, " 52.

Figure 8.

Male nudists surging toward the sun. From Hans Surén, Der Mensch und die Sonne (1924).

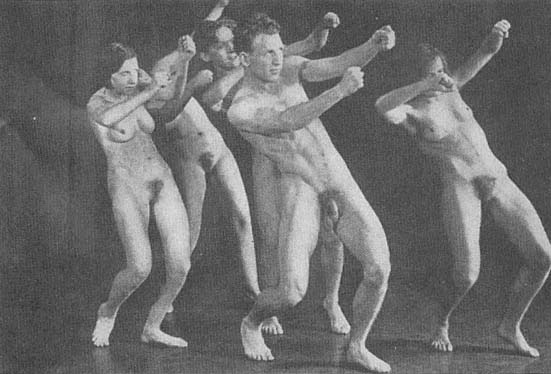

Figure 9.

Male and female nudists exercising together indoors at the Koch school in Berlin.

From Adolf Koch, Körperbildung/Nacktkultur (1932).

Figure 10.

Students of the Hagemann school in Hamburg. From Hagemann,

Über Körper und Seele der Frau (1927).

Figure 11.

Woman gymnast of the Hagemann school.

From the Joan Erikson Archive of the Harvard Theatre Collection.

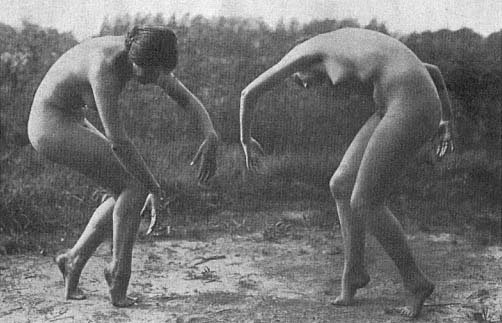

Figure 12.

Brother and sister nudists. Photo by Lotte Herrlich, from Herrlich, Seliges Nacktsein (1927).

Figure 13.

Claire Bauroff, Vienna, 1925. Photograph by Trude Fleischmann, from Pastori (1983), 44.

Figure 14.

Grete Wiesenthal performing Pantanz, Vienna, 1910.

Woodcut by Erwin Lang, from Lang, Grete Wiesenthal (1910).

Figure 15.

Dancer at the Elisabeth Estas school in Cologne, 1927.

From RLM, plate 91, photographer unknown.

Figure 16.

Drawing by Hata Deli. From Ernst Schertel,

Der erotische Komplex (1932).

Figure 17.

Dancer at the Ida Herion school in Stuttgart.

Photo by Alfred Ohlen, from Adolphi and Kettmann,

Tanzkunst und Kunsttanz (1927).

Figure 18.

Dancer at the Ida Herion School.

Photo by Ohlen, from Adolphi and Kettmann.

Figure 19.

Dancer at the Ida Herion School.

Photo by Ohlen, from Adolphi and Kettmann.

Figure 20.

Dancers at the Ida Herion school in Stuttgart.

Photo by Paul Isenfels, from Isenfels, Getanzte Harmonien (1926).

Top: Figure 21.

Dancers at the Ida Herion School. Photo by Isenfels, from Isenfels.

Bottom: Figure 22.

Dancers at the Ida Herion School. Photo by Isenfels, from Isenfels.

Figure 23.

Watercolor study by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner for the "Color Dance"

mural in the Folkwang Museum, Essen, ca. 1932, from Froning (1991), 97.

Figure 24.

Social dancing in a sleazy Berlin bar.

Watercolor by Jeanne Mammen, ca. 1929,

from Jeanne Mammen 1890–1976 (1978).

Figure 25.

Chorus girls in a Berlin nightclub, 1919, before the advent of Girlkultur ,

with spectators and performers in a puzzling relation to each other.

Photographer and source unknown, reproduction from postcard.

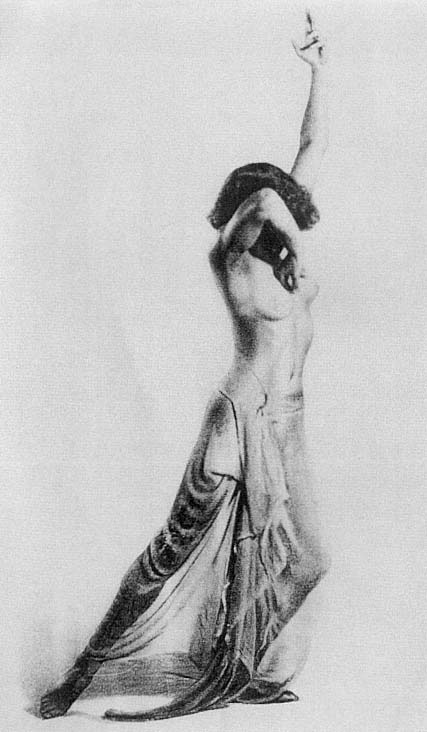

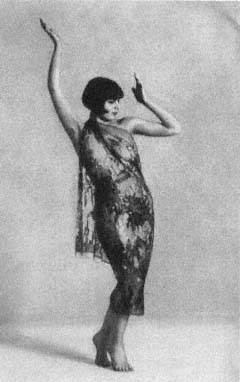

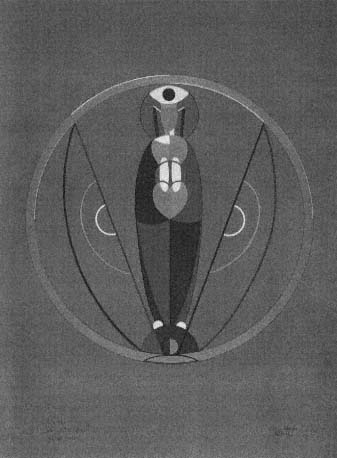

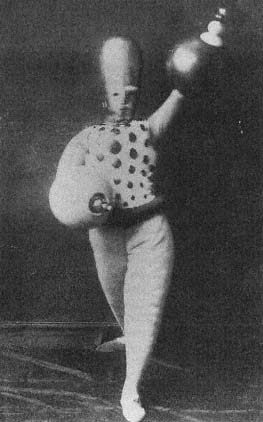

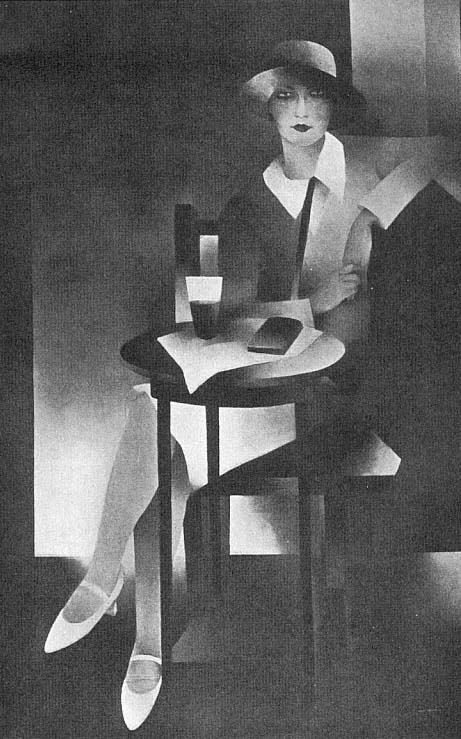

Figure 26.

Anita Berber and Sebastian Droste in a pose

from their St. Sebastian dance, Vienna, 1922.

Photo by Madame D'Ora, from Anita Berber and Sebastian Droste,

Die Tänze des Lasters, des Grauens und der Ekstase (1922).

Figure 27.

Outdoor movement choir performing Laban

improvisation exercises, ca. 1924 from Laban,

Gymnastik und Tanz (1926).

Figure 28.

A sketch, ca. 1924, by Rudolf Laban attempting to

describe human movement as a dynamic

geometric form. From Ullmann (1984), 34.

Figure 29.

Mary Wigman's Zweitanz (Studie) (1927);

Wigman is the figure on the left. Photo by

Charlotte Rudolph, from Rudolf Bach,

Das Mary Wigman-Werk (1933).

Figure 30.

Masked solo figure from Wigman's Totentanz (1926).

It was quite unusual for a Wigman dancer to perform on a carpeted

rather than polished wood surface. From Rudolf Bach,

Das Mary Wigman-Werk (1933).

Figure 31.

Image of the "prophetess" section of Wigman's Frauentänze (1934).

Photo by Charlotte Rudolph, from Wigman, Deutsche Tanzkunst (1935).

Figure 32.

Female Loheland (Fulda) student projecting

ambiguous sexual identity, ca. 1920. From Fritz

Giese, Körperseele (1924), plate 31.

Figure 33.

Page 323 of the Základy rytmického telocviku sokolského (1929),

one of hundreds of exercises in this huge manual on the Sokol system

of movement education, probably the most comprehensive

account of Dalcrozian movement pedagogy ever published.

Figure 34.

Interaction between male bodies performing Swedish

gymnastics. Leipzig, ca. 1926, from a contemporary postcard.

Figure 35.

Design by Lothar Schreyer for Maria im Mond , Weimar, 1923,

with robot female idol perched on "dance shield." From DS 70.

Figure 36.

Image from Schlemmer's The Triadic Ballet ,

ca. 1925. Photo source unknown.

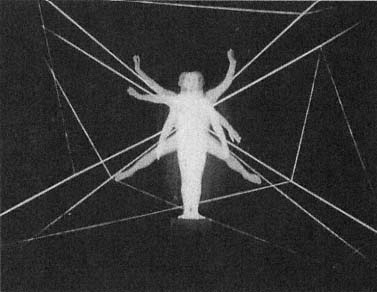

Figure 37.

Experimental dance at the Bauhaus, Dessau, ca. 1927. Photo by Lux Feininger,

Copyright The Oskar Schlemmer Theatre Estate, 79410 Badenweiler,

Germany, Photo Archive C Raman Schlemmer, Oggebbio, Italy.

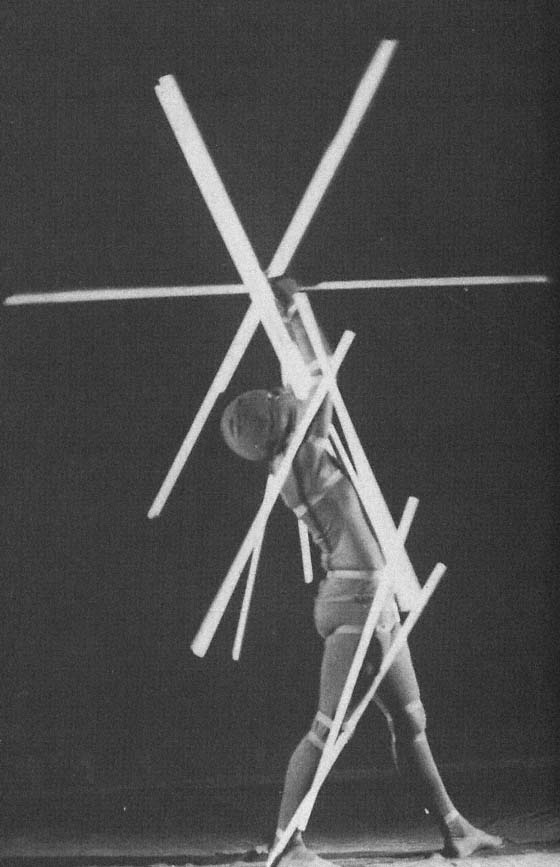

Figure 38.

Image of the Staff Dance (1928–1929), performed by Manda van Kreibig

at the Bauhaus, Dessau. Copyright The Oskar Schlemmer Theatre Estate,

79410 Badenweiler, Germany, Photo Archive C Raman Schlemmer, Oggebbio, Italy.

Figure 39.

Edith von Schrenck. Photograph by

Hanns Holdt. Compare with Figures 40 and 41.

Figures 40 and 41.

Edith von Schrenck's Kriegertanz and Polichinelle (1919). Lithographs by

Ottheinrich Strohmeyer, from (left) Buning, Dansen en danseressen (1926),

and (center and right) Schrenck (1919).

Figure 42.

Grit Hegesa performing Groteske , Rotterdam, 1917.

Etching by Herman Bieling, from Netherlands Theatre Institute.

Figure 43.

Grit Hegesa dancing, Rotterdam, 1918.

Painting by Herman Bieling, from Netherlands Theatre Institute.

Figure 44.

Grit Hegesa, Berlin, ca. 1925. Painting by Emil van Hauth,

from The Studio , 92/401, 14 August 1926, 134.

Figure 45.

The Dancer Charlotte Bara , Worpswede, 1918.

Painting by Heinrich Vogeler from Küster,

Das Barkenhof Buch (1989), 113.

Figure 46.

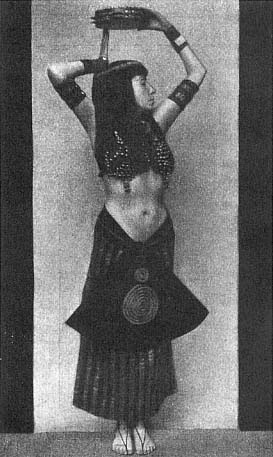

Sent M'ahesa in a pose from an Egyptian dance, Munich, ca. 1915.

Photographed by Wanda von Debschitz-Kunowski, from HB, plate 24.