War and the Production of Normal Neurosis

Thus sensitized to how their own most important professional obligations were being shaped by the wartime context, clinicians were quick to see social factors at work in the production of the mental troubles they treated. Their conclusion? Individuals who became psychologically unbalanced were responding quite normally to an abnormal environment. "The situations of war, for the civilized man," reasoned psychiatrists Roy Grinker and John Spiegel, "are completely abnormal and foreign to his background. It would seem to be a more rational question to ask why the soldier does not succumb to anxiety, rather than why he does."[52] William Menninger went so far as to call war a "pathological outpouring of aggression and destructiveness [that] might well be regarded as a psychosis."[53]

That mental breakdown was to be expected under extreme conditions may have appeared obvious in retrospect, but it was not at first. It took time and effort to determine that men in combat units snapped in far greater numbers than did those serving in noncombat capacities and

that symptoms in the air forces differed systematically from those in the ground forces. These were patterns that predisposition simply could not explain. The sheer numbers of cases seen by military clinicians—NP admissions alone totaled one million, representing 850,000 individuals—finally led them to view the typical psychiatric casualty not as an intrinsically predisposed or mentally disordered individual but as a perfectly ordinary person under incredible strain—an "Everyman."[54] "It became obvious that the question was not who would break down, but when ."[55]

Psychiatrists did not discard entirely their conviction that the mental troubles of given individuals were configured in highly personal ways, conditioned especially by family background and childhood experience. They could not have done so and remained clinicians, after all. Dispensing with the study of individual mental health would have eviscerated the very basis of psychological treatment and left them no option but to become social engineers.

While few clinicians embraced this label explicitly, the movement toward an environmental understanding of wartime breakdown pushed the concerns of clinical professionals in decidedly social directions. According to William Menninger, the essence of the clinical task was to treat the whole personality in the context of the whole environment. This assignment was enormous, to say the least. Human personality consisted of "everything we are, have been, and hope to be," and environment was nothing less than "everything outside ourselves, the thing to which we have to adjust—our mates and our in-laws, the boss and the work, friends and enemies, bacteria and bullets, ease and hardship."[56]

Mental health was present when the struggles within and between personality and environment could be routinely managed through adjustment; mental disturbance occurred when this effort overwhelmed the individual. It stood to reason that unusually forceful conflicts in either the personality or the environment—such as war—could throw mental health out of balance. Psychiatric methods would therefore have to be closely coordinated with theory and research in the social and behavioral sciences. Only a socially sensitive clinical vision could encourage the type of wise policy-making that would produce a postwar environment hospitable to mental health.

Such views clearly anticipated the activist ethos of postwar clinical work and the innovative community psychology and psychiatry movements, whose leaders were World War II clinicians like William Men-

ninger (see chapter 9). In the meantime, revealing the precise causes of mental trouble in any given case became a delicate balancing act between individual psychological patterns (determined by personal history) and changing levels of environmental hardship (in the immediate context of war). Since war was constantly acting upon the soldier and the soldier's circumstances, mental health and illness could no longer be considered fixed states.

Clinical vocabulary reflected the discovery that mental troubles could appear in the most normal of men and displayed the concomitant etiological emphasis on social factors. "War neuroses" clearly tied neuroses to war and "stress" implied that mental pressures were largely external. "Operational fatigue" (used in the air forces), "combat fatigue" (used in the navy), and "combat exhaustion" (used in the army) suggested that the weariness experienced by soldiers was somehow occupationally induced. On the other hand, clinicians who prided themselves on their terminological precision often derided such terms as useless and misleading. "Operational fatigue," they complained, was not even an accurate description. Because it had nothing to do with fatigue, individuals suffering from it would not recover with rest. It was nothing but a "wastebasket diagnostic term."[57]

The statistical picture that emerged from clinicians' diagnostic choices also fostered the impression that most mental trouble was due to the war. Ninety percent of all hospitalized cases were classified as psychoneuroses and personality disorders, relatively minor troubles in the world of mental disorder. Only 6 to 7 percent conformed to the psychotic profile of the traditional mental patient.[58] The label "psycho-neurotic" was used extensively because it functioned as a summarizing term for a number of more specific classifications, denoting a diversity of emotional reactions: anxiety, fear, hostility, guilt, depression, and physical manifestations like nausea and vomiting when they appeared as recurring psychosomatic symptoms.

Clinicians attempted to distinguish one particular "reaction" syndrome from the next with great care and the result pushed patterns of psychiatric classification away from the neurological emphases of the past, toward encompassing a wide variety of normal mental troubles.[59] Several diagnoses, for example, were grouped under the category "transient personality reactions to acute or special stress," which emphasized the immediate pressures operating on the suffering individual, the absence of past psychological problems, and the likelihood of complete recovery in the future. Transient personality reactions were defined as

follows in the army's official Nomenclature and Method of Recording Diagnoses: "A normal personality may utilize, under conditions of great or unusual stress, established patterns of reaction to express overwhelming fear or flight reaction. The clinical picture of such reactions differs from that of neuroses or psychoses chiefly in points of a direct relationship to external precipitation and reversibility. In a great majority of such reactions, there is an essentially negative historical background."[60] A majority of more specific diagnostic labels in this and other general categories of mental disorder—from "acute situational maladjustment" to "anxiety reactions"—appeared to share a definite relationship to the individual's actual experience. War transformed clinical nomenclature.

In sum, clinicians diverged sharply from their traditional preoccupation with illness and abnormality, fixating instead on the normal. Immersed in managing the psychological symptoms of individuals, they nevertheless came to appreciate their own great potential to prevent the slide toward illness and irrationality in mass populations, exactly as nonclinical experts did. War taught them that their historical commitment to treating mental illness at the point of insanity and gross disability was terribly reactive and extremely inefficient. Why wait around for people to deteriorate into pathetic mental cases? Far more forward-looking would be a professional ideology of early intervention in cases of mental trouble, even systematic environmental design with an eye toward producing mental health—presumably so that mental illness would dissipate to a point where it required only minimal professional attention.

While it was not in clinicians' power to redesign the wartime environment so that mental trouble could be prevented entirely (i.e., end the war), they did begin to make suggestions that sounded remarkably like those of their policy-oriented counterparts. John Appel, head of the Mental Hygiene Branch in the Psychiatry Division of the army's Office of the Surgeon General, led much of the effort to reform the military's overall environment through policy changes that would have an impact on personal well-being. In the name of clinicians' twin duties to individual soldiers' mental health and military efficiency, he called for fixed tours of combat duty. Knowing exactly how much time they could expect to spend in combat would both increase soldiers' efficiency and decrease their rates of mental breakdown. The indefinite tours that were routine in the war's early years had, John Appel observed, depleted human resources to the point of utter uselessness. A

policy of limiting combat to 120 days was finally adopted in the spring of 1945.[61]

Other measures geared to preventing mental trouble through environmental adjustment included improving leadership training, boosting group cohesion, establishing rest camps, and feeding soldiers good food. These reforms should sound familiar. Very little of consequence distinguished their clinical advocates, who were devoted to environmental tinkering, from the psychological experts who operated on a policy level and were examined in chapters 2 and 3. Even though the details of their daily work remained rather different, the war advanced the integration of their overall perspectives.

There were, of course, genuine differences in orientation. Clinical theories and skills were especially suited to engineering the internal, psychological environment, and it was here that clinicians excelled. For example, while clinicians were just as dismayed as nonclinical experts to learn that the average soldier did not understand the political aims of the war, their greater familiarity with the interior landscape of irrational drives and unconscious motivations allowed them to respond more hopefully to this piece of distressing news. According to William Menninger, psychiatric interviews brought military clinicians to the same unfortunate conclusion that pollsters in the Army Morale Division's Research Branch had reached. "Only a small proportion of the entire armed force was capable of feeling an emotional urge toward the real purpose of American participation in World War II."[62]

William Menninger and others involved directly in mental breakdown and recovery, however, drew on their clinical experiences and determined that there were worse things than not knowing what the war was all about. They pointed out that gut-level loyalties to buddies, automatic obedience to unit leaders, and hatred of the enemy were more important to military cohesion and the will to fight than was comprehension of the evils of fascism or the virtues of liberal democracy. "The Atlantic Charter, The Four Freedoms and postwar aims do not stir the soldier to his best efforts; only good morale within his own small group and the hope of getting home soon can do that," wrote Roy Grinker and John Spiegel, two psychiatrists who served in the Tunisian campaign in 1943.[63] "Fortunately," they added, "strong intellectual motivation has not proved to be of the first importance to good morale in combat."[64] If rational moral was weak morale, then it followed that emotion—not reason—was the source of military strength. "The will to fight must be forged out of the fiery furnaces of fear and

aggressiveness; if we are to win. We have to win this war with our hearts as well as our heads and hands. Ideas alone are too pallid."[65]

The following sections briefly describe two particular areas of wartime clinical work: self-help literature designed by experts for mass consumption and the wartime practice of psychotherapy with mentally troubled soldiers. Although they employed clinical experts in different capacities, both advocated emotional management on the individual level as an indispensable element in effective military functioning and eventual victory. The process of normalizing clinical ideas and experiences, apparent in each case, provides the basis for the postwar developments that will be explored in chapters 9 and 10.

Self-Help: Emotional Preparedness as Military Strategy

The clinical drift toward prevention surfaced in preventive efforts to promote psychological self-help among normal soldiers. Advice was geared to the personal management of emotions under stress—fears and resentments, in particular—and much attention was paid to the distinction between normal and abnormal reactions in an effort to reassure soldiers that a certain amount of trepidation was to be expected as they adjusted to military life. Advice was typically packaged in the form of lectures to new recruits, short pamphlets or easy-to-read books, and popular films. In these efforts, science always gave way to simplicity. The point was to "show the men that the army was interested in their feelings" and help them adjust, not to exhibit the fine points of psychological knowledge (figs. 4-10).[66]

Edwin Boring, a prominent psychologist involved in the war effort, thought such wartime self-help literature so successful that he predicted the postwar years would expand the market for such products into radio, television, and movies and change the emphasis from controlling negative emotional states to attaining contentment and peace of mind: Fear in Battle (an actual example of wartime self-help literature, discussed below) would be transformed into "How to be Happy —at every drug store" (his prophetic fantasy of where the future might lead).[67] The dissemination of psychological knowledge through popular channels, Boring speculated, would "increase personal maturity, help social tolerance and progress, and enlarge the democratic communal base of thinking."[68]

Boring's glowing review of the genre, however typical of the period's extravagant optimism and abiding faith in the democratic consequences

Figure 4. Graphic illustrations of normal and abnormal reactions to military

life, routinely shown to soldiers as part of the war's preventive psychiatry

program. Photo: Copyright American Medical Association, from War Medicine 5

(February 1944):85. Panel A illustrates the normal brain, consisting of emotion

and body control, which are both subordinate to reason (the "think box").

Psychiatrists stressed that it was entirely normal to experience resentment

and fear. Panel B illustrates that it is also normal for resentment to increase

when soldiers are first inducted and forced to leave their old lives behind.

Panel C illustrates that soldiers who employ normal mental techniques, such

as humor and mental toughness, can overcome these feelings. Notice that

resentment expands to fill a large part of the brain when anger and other

emotions increase in panels B and C. When resentments persist through

brooding and homesickness, soldiers were warned, the large area of the

brain devoted to resentment takes over precious room that reason needs to

function, making military training difficult or even impossible. Displacing

body control also creates problems for soldiers by giving rise to physical

complaints with origins in an abnormal mental attitude—too many feelings

and not enough room for the "think box." Panel D illustrates the normal

body systems (heart and digestion) that accompany a normal mental attitude.

Panel E illustrates how these same body systems respond to an

abnormal mental attitude.

Figure 5. Graphic illustrations of normal and abnormal reactions

to military life, routinely shown to soldiers. Photo: Copyright American

Medical Association, from War Medicine 5 (February 1944):87.

Panel A shows that when the military deprives men of their customary

privacy, privileges, and opinions, soldiers respond at first

with increased resentments—this is normal. Panel B shows soldiers

that by letting off steam, they can shrink resentment down to size

and get the brain back into a normal arrangement.

of true science, was also self-interested. He was coeditor of Psychology for the Fighting Man, one of the most important efforts in the self-help category. The brainchild of the Emergency Committee in Psychology, the book was part of psychologists' consciously organized effort to "sell" the notion of their professional contribution to the U.S. military.[69] Marjorie Van de Water, a professional journalist who specialized in popular science writing, was hired to turn the sometimes obscure language of experts into prose the average GI could easily read and understand.

Numerous checklists were included, for example, offering simple instructions about what to do or think in a variety of situations. Staying awake, speeding the training process, and recognizing "mental danger signals" were each considered in turn, along with other situations common in military life. The experts had numerous tips for soldiers worried about "how to fight fear" or confused about "how to win friends in foreign lands." Among them were seeking physical contact with friends, trying hard to understand strange customs, and suppressing disapproval of behavior they thought too bizarre to respect.[70] Although Boring

Figure 6. Graphic illustrations of normal and abnormal reactions to military life,

routinely shown to soldiers. Photo: Copyright American Medical Association,

from War Medicine 5 (February 1944):90. Panel A illustrates the normal brain again.

Here, reason is in the driver's seat, body control is well regulated from the main

switchboard, and the emotions are chained and under rational control. Psychiatrists

stressed, once again, that fear (located in the center position) was present in every

normal person. Panel B shows the normal reaction to unknown dangers: reason and

body control temporarily leave their posts and fear begins to get out of control. At

this point, psychiatrists stressed that soldiers' training would help them identify this

situation and quickly restore reason to its normal place of control in the brain. If

soldiers neglected the lessons of preventive military psychiatry, however, panel C

would result. Fear would be greatly magnified and emotion would threaten to

overwhelm reason. In panel D, despair is added, and fear takes over completely.

Now, it is fear that is in the driver's seat: both body control and reason have

been knocked out. Soldiers were instructed that with reason out of the picture,

they would "freeze," becoming pushovers for the enemy. The only hope was

to use normal techniques—courage or rage—to restore the abnormal brain to

its normal state. Panel E illustrates this ultimate struggle for normalcy. Reason

pulls fear out of the driver's seat and resumes its dominant mental

position, while body control restores physiological equilibrium.

Figure 7. From the cartoon booklet "Story of Mack and Mike."

Figure 8. From the cartoon booklet "Story of Mack and Mike."

Figure 9. From the cartoon booklet "Story of Mack and Mike."

Figure 10. From the cartoon booklet "Story of Mack and Mike."

privately derided this how-to style as "soft and popular," and one reviewer dismissed the condescending "birds, bees, and flowers" tone of the book, there was no arguing with the project's success.[71] The book was published in 1943 after sections were serialized; it eventually sold around 400,000 copies at 25 cents apiece.

Authored collaboratively by fifty-nine experts and more than 450 pages long, the book covered a range of topics, including a number that were not strictly clinical. Its general purpose was to bring up-to-date psychological knowledge to the masses and explain to ordinary soldiers the challenge of ensuring satisfactory psychological resources for military purposes. "The Army has a perpetual problem of psychological logistics," the authors noted, "a problem of the supply of motives and emotions, of aptitudes and abilities, of habits and wisdom, of trained eyes and educated ears. How does it get the mental materiel to the right places at the right time?"[72] The rationale for psychological personnel testing was painstakingly explained in the book, as were the basics of vision and hearing, propaganda, and psychological warfare.

Most of the book, however, concentrated on loaded topics of great concern to individual soldiers: morale, food, sex, neurosis, panic, and personal adjustment. How to cope with sexual deprivation was a major subject and on this, as on other topics, the book's tone veered unsteadily between authoritative prescription and empathetic reassurance. If masturbation became a regular habit, or a preferred form of sexual activity, the authors counseled, "it is definitely abnormal." "If it is only resorted to as a temporary outlet," they added, it could do little mental or physical harm.[73] Prostitution could also seriously hamper military efficiency, the experts warned, and no true sexual satisfaction could be found in promiscuous contacts. But adjusting to the sexual strains of military life was no simple matter either. Everything from unusual fantasies to homosexuality could be understood as a normal response to abnormal circumstances, at least sometimes. They were inappropriate, but they were also likely to be temporary. On masturbation, prostitution, and other sexual topics, Psychology for the Fighting Man tried to balance clear instructions and friendly reassurance. "It is not easy for a man to get his sexual life into wise and proper adjustment."[74]

Homosexuality was a major, ongoing preoccupation for clinical experts throughout the war years, and their work on the topic was not by any means limited to the self-help literature.[75] Because homosexuality was considered a special threat to military discipline and good morale, anyone with such proclivities was automatically rejected from the armed

forces. But since few homosexuals announced themselves upon induction, subsequent revelation of homosexuality was an official pretext for the psychiatric hospitalization and dishonorable discharge of thousands of soldiers and sailors.

But clinical opinion about homosexuality changed decisively during the war years and the shift bolstered the view that mental health experts were the very incarnation of modern enlightenment. The prewar consensus held that homosexuality was nothing but depraved sexual behavior in otherwise ordinary people. By 1945 clinical research made it appear that homosexuals had unique psychological profiles; in other words, they were not ordinary people. The military's practical response to homosexuals simply had to change, according to some clinicians. "The crude methods of the past have given way to more humane and satisfactory handling of the problems of the homosexual. No longer is it necessary to subject cases that are so definitely in the medical field to the routine of military court martial."[76] Because it involved psychological identity, homosexuality ought to be treated with compassionate psychotherapy rather than criminal penalties. Sexual deviance was no simple matter of wicked behavior; hence, punishment could not fix it. Only experts with a grasp of the personality as an integrated whole could hope to illuminate—let alone alter—the psychological processes implicated in the production of homosexuality.

Psychology for the Fighting Man managed to present both old and new views on this topic, capturing this fascinating change of attitude in progress. Soldiers were counseled that meeting heterosexual needs through homosexual behavior was understandable, even if it was also degenerate. Normal soldiers with such impulses should fight hard to control them if they could (two practical rips from the experts were praying and concentrating on killing the enemy), but, whatever happened, they would probably be just fine once they returned home. On the other hand, the experts indicated that homosexuals were a recognizable type whose perversion—if forced upon unsuspecting soldiers—deserved court martial and prompt discharge. In the first case, homosexuality was a normal response to an abnormal situation. In the second, it constituted a distinct clinical syndrome: "Attempts to reform such men are almost always futile."[77]

Belief in the possibility and desirability of reforming the self, although not necessarily applicable to sexual preferences and behaviors deemed deviant, was nevertheless at the core of most of the self-help effort. "Adjustment" was a term as likely to designate efforts to post-

pone or prevent mental breakdown through self-education and preparedness as it was the treatment of mental shock with professional techniques such as psychotherapy.

For obvious reasons, fear was an emotion especially in need of adjustment, and its management was a major theme in Psychology for the Fighting Man. The first step in the process of emotional management was reassuring explanation. Fear, according to the experts, was entirely natural and healthy when it was a response to actual external danger. Moreover, it was "nature's way of meeting in an all-out way an all-out emergency" and it was "useful in mobilizing all the body's resources."[78] Whether in combat or in anticipation of combat, all soldiers who were honest with themselves experienced fear.

The process through which fear was normalized, it is important to note, depended on the sex-segregated nature of the combat experience, as well as the overwhelmingly male ranks of clinical experts themselves. Roy Grinker was one of a number of professionals who identified wartime contact with healthy young men experiencing stress as the key to clinicians' postwar gravitation toward normal psychology.[79] Generalized fears had, after all, long been attached to the phenomenon of hysteria in women, an unappealing, if still fascinating, syndrome marked by extreme dependence, emotional superficiality, and a heavy dose of melodrama. Fear of combat, however, was uniquely masculine, and could therefore circumvent the taint of irrationality and abnormality that marked all the terrors clinicians treated in the female gender. Women felt "anxiety," rather than "fear," and the difference was crucial. Because the source of soldiers' combat fears was obvious and environmental, their feelings were normal and clinicians readily empathized with their nervousness. In contrast, women's feelings could be vague, difficult to explain, and farther from clinicians' own experience. They tended therefore to be interpreted as abnormal anxieties with purely intrapsychic roots. The purpose of the self-help literature, in any event, was to help soldiers strike a balance between permitting themselves to feel normal emotions (like fear) when it was safe to do so and strictly regulating them when it was not. Left unmonitored, fears could grow into anxieties, ceasing to be comprehensible emotional reactions to real peril and becoming states of chronic inner disturbance requiring treatment.

John Dollard, a member of the Yale Institute of Human Relations and a consultant to the Research Branch of the army's Morale Division, authored several self-help pieces on this particular topic, including a

short pamphlet, Fear in Battle, and the even shorter "Twelve Rules on Meeting Battle Fear."[80] Both were intended to reassure men that fear was no cause for shame or embarrassment. Even extremely unsettling psychological experiences, Dollard advised, were perfectly ordinary amid the extraordinary circumstances soldiers faced. Emotional advice "will help any soldier with the guts to face the ordinary fact that everyone gets scared in battle."[81]

Characteristic of advice on this and other topics, and of the normalization process in general, was the insistent refrain that insight—meaning psychological self-consciousness—was the most effective method and barometer of psychological self-mastery; practiced introspection was both technique and goal. Calm, rational understanding of self was a kind of emotional armament, as necessary to the effective prosecution of war as to the goal of individual self-defense and preservation. "Keep remembering that being scared makes you a smarter soldier—and a safer one," was Dollard's rule number 3. But such comforting words were hardly an adequate guide to soldiers facing tangible horrors on the battlefield. So Dollard also prescribed specifics on suppressing fear when necessary: "Make a wisecrack when you can" and "Never show fear in battle" were two of his recommendations.[82] Nor did he neglect to remind soldiers to adopt regular habits of emotional communication. "Talk about being scared—any time you want to talk about it. Everybody gets afraid in combat. You're no exception, and neither are the rest of the men in your outfit. It's a common, every day battle experience for all normal men. It always has been—in every war in history. So there is no reason in God's world for not talking about it—during a lull in the fight, or afterward. And if you do, it helps next time—it helps every time."[83]

Wartime self-help literature attempted to communicate several different things at once. Because it provided refreshing clarity and ready sympathy to countless individuals living without much of either, its appeal was not exactly mysterious. Moreover, it highlighted the potential helpfulness of clinical expertise to ordinary people. Soldiers who absorbed the lesson that they could take steps to prevent mental breakdown themselves were living proof that the meanings of war and of mental health were both rapidly changing. Owning up to feelings like fear was defined as key to managing the military's "mental material" precisely because victory in war required the active mastery of individual subjectivity. If they agreed to strive for a state of psychological insight, experts promised soldiers that, in return, they would help them fulfill

their patriotic duty, demonstrate their emotional enlightenment, and survive the war in body as well as in spirit.

Professional Help: The Psychotherapeutic Frontier Expands

Not all cases of wartime mental trouble, of course, could be efficiently managed by providing self-help literature or exhorting soldiers to circumvent breakdown by taking responsibility for their own emotional control. As the years wore on and psychological casualties mounted, the challenges clinicians had initially faced in screening predisposed individuals out of the military began to pale in comparison with treating masses of mentally troubled soldiers and returning them to health. Clinicians turned increasingly to psychotherapeutic means of accomplishing this task.

Before the war, psychotherapy had been associated largely with the elite office practice of psychoanalysis (the original talking cure) or with a range of techniques employed by psychiatrists functioning in the institutional context of state hospitals. In both cases, psychotherapy was an unusual experience for which the prerequisites were extreme wealth, avant-garde curiosity, or something close to insanity. Psychotherapy was not relevant to ordinary people. If anything, it was stigmatizing.

Wartime necessity permanently altered this pattern by normalizing psychotherapy. Clinicians' efforts to cope with anxieties and neurotic symptoms among soldiers introduced psychotherapeutic techniques to millions for the first time. Many of the somatic techniques used during the war had been used before with civilian mental patients—insulin injections, electroshock, and heavy sedation among them—and cases of severe (i.e., psychotic) disorder and total collapse were usually segregated and hospitalized, much as they had been before the war.

But the time and personnel pressures endemic to wartime clinical work, along with experts' obligations to serve the military's institutional need for a steady supply of dependable human resources, underscored "the necessity for therapy to adapt itself to a more or less inflexible military framework."[84] This forced clinicians to devise a menu of creative psychotherapeutic alternatives and shortcuts "which give promise of returning a maximum number of men to duty within a minimum of time and with techniques which are feasible in the active theatres of combat."[85]

For the most part, these techniques fell into the category of talking

cures, even if the talking was brief and, at times, chemically facilitated by various drugs (figs. 11 and 12). Individually and in groups, soldiers discussed their feelings, combat experiences, and personal histories. The primary goal of such treatment was to help mentally troubled individuals recoup their previous level of function and return to military service, but these practices also unquestionably encouraged new levels of psychological self-exposure and self-consciousness and insinuated that these characteristics were necessarily present in healthy individuals struggling to recover from momentary mental setbacks. The result was that basic definitions of clinical practice changed. From all appearances, larger and larger numbers of normal individuals benefited from psychotherapy and many more and varied activities proved therapeutic.

Psychotherapeutic treatment for the masses placed a premium on clinicians' time and energies. Treatment was as rapid as possible. The logistics of its provision, however, changed as the war altered clinicians' views of mental distress and its causes. For example, cases of combat breakdown were initially evacuated to hospitals in the rear because they were assumed to be limited to predisposed individuals who had escaped detection at the point of screening. Early in the war, when the emphasis was still on prediction rather than treatment, clinicians believed that predisposed men were unlikely to be militarily productive, once pushed beyond their low mental thresholds. As time passed, evidence mounted that mental breakdown was normal under the pressures of war and doubt was cast on the predictive value of predisposition. "Every person, no matter how strongly integrated," noted one psychiatrist, "has his breaking point when sufficient stress is applied." [86] Brief military service was all that was required to convince most other psychiatrists. Treatment of most combat mental cases subsequently evolved from trauma-oriented procedures to something more like psychological first aid.

It was 1943 when psychiatrists were sent to combat areas for the first time.[87] Altering the geographical location of clinical work directly reflected the recognition that clinical efforts should be aimed at the normal neurosis produced in ordinary people under the abnormal conditions of combat. According to Grinker and Spiegel, psychiatrists with combat experience in North Africa, "The realities of war, including the nature of army 'society,' and traumatic stimuli, cooperate to produce a potential war neurosis in every soldier. When predisposition is combined with adequate stimuli of a certain type or degree, a neurotic breakdown is precipitated, which constitutes an illness and requires treatment."[88]

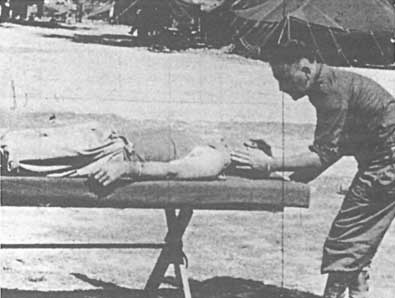

Figure 11. A military psychiatrist in the Philippines interviews

a patient in his outdoor office during World War II.

Figure 12. Hypnosis was one of the psycho- therapeutic

techniques used on soldiers during World War II.

After 1943 the first stop for mentally wounded soldiers was a clearing station close to the front, where they were immediately sedated so that they could sleep. After adding some good food and a bath to a decent interval of rest, 40 percent of these cases had recovered sufficiently to be returned to combat by the third day. Those who did not bounce back so quickly proceeded to the second stop for combat casualties, an "exhaustion center." Here, patients were sedated again, then offered some form of very brief psychotherapy, often in combination with drugs like sodium pentothal, which was administered for the sole purpose of speeding up the therapeutic process through "narcosynthesis."[89] Five to eight days later, another 20 percent of the men were sent back to their units.[90] Not only were these new procedures efficient from the military point of view (many of these cases would previously have been removed from active service altogether only to languish in costly and labor-intensive hospital settings), but they seemed to indicate that timely application of clinical attention to relatively mild instances of mental trouble significantly affected the outcome. Many recovered sufficient mental balance to continue military service: many in combat duty, others in noncombat capacities. The rest were evacuated (fig. 13).

Of course, important theoretical differences remained in how clinicians understood and treated war neuroses. Freudian psychology would emerge from the war as the dominant paradigm among clinicians. Partisans, like psychiatrists Roy Grinker and John Spiegel, considered predisposition (by which they meant past history, especially childhood socialization patterns and familial relationships) to be highly relevant in the precipitation of mental trouble and the determination of a given individual's neurotic symptoms. Yet they also embraced the position that the traumas present in the wartime environment had a direct bearing on mental breakdown. "Sick or well," they argued, "every combat soldier reacts to the stresses of the harsh realities of war according to how his previous psychological patterns have prepared him, and he reacts only to the proper quantifies of specific stimuli to which he is sensitized. In other words, in our opinion, the neuroses of war are psychoneuroses. "[91] Insisting that all war neuroses were psychoneuroses was simply another way of saying that war was mentally unbalancing not in and of itself but because it mobilized old, often unconscious, emotional conflicts residing in the individual psyche, conflicts that were the most fundamental and authentic sources of mental symptoms. The ultimate point of psychotherapy was to untangle the knots tying previous psychological patterns to current psychological reactions. Clearly, the the-

Figure 13. World War II neuropsychiatric casualties in New

Guinea, ready for their evacuation to the United States.

oretical balance between psychological history and current circumstance meant that the job of delivering long-lasting psychological relief combined a detective's investigatory zeal with a counselor's patient wisdom. Psychotherapy entailed highly disciplined effort, painstaking insight, and a lot of time.

These were luxuries unavailable during the war. Grinker and Spiegel, along with other clinicians, sometimes regretted that the therapies they recommended—from food and sleep to brief talking cures—were inadequate to do the job of real emotional healing. Keenly aware that wartime pressures forced them to place superficial Band-Aids over deep mental wounds, they bemoaned their own habit of providing short-term "covering" techniques rather than long-term "uncovering" ones.[92] Like their policy-oriented counterparts, however, World War II clinicians accepted without question that shortcuts were essential. The point was not to achieve perfect mental health and insight, or scientifically validate clinical services, but fortify the military's flagging psychological resources. Clinicians agreed that temporarily interrupting the most immediate source of neurosis—namely combat danger or fear of

it—was a first step in the process of emotional healing. Other, more ambitious steps would simply have to wait.

In the meantime, clinicians made creative use of the resources available to them. Like food and rest, everything from vocational training to good weather was eventually drafted into clinical service and relabeled "therapeutic." Clinicians could and did explain exactly why satisfying work and hot meals were psychologically beneficial and, as we have seen, they used their authority to back efforts to humanize military life in the name of preventing mental trouble. In the end, however, they knew it was not self-evident that such undertakings required their unique clinical talents. Common sense might be as much a resource as clinical expertise, and far less expensive, if the overall goal were to make the military a more hospitable place to spend time. Grossly overreaching therapeutic frontiers threatened to undermine their authority. Extending therapeutic frontiers within reason, however, could legitimate a larger sphere of operation.

In contrast to food and sleep, the practice of individual psychotherapy remained clinicians' singular contribution. Exclusively associated with clinical experts, psychotherapy claimed to alleviate mental anguish directly by establishing a helpful relationship between a troubled individual and a trained psychotherapist. The clinical theory underlying much wartime psychotherapeutic practice was Freudian in at least a rough sense, and psychodynamic approaches reached their zenith in the postwar years. Even though time and staff shortages precluded the practice of anything resembling classical psychoanalysis, clinicians held fast to an analytical version of the therapeutic relationship, however abbreviated by war. Only a deliberate professional effort, infused with insight, could successfully release whatever repressed emotions were at the root of soldiers' dysfunctional symptoms and strengthen their capacity to adjust more adeptly to the stresses of war.

Even this supposedly unique professional relationship, however, threatened at times to dissolve in the face of simple common sense. Indeed, therapists themselves were often the first to point out that em-pathetic attention was usually helpful to troubled people, whether offered by professionals, friends, or family members. Because so few non-psychiatric clinicians had any meaningful psychotherapeutic training before the war, military psychotherapists were generally advised to rely on intuition in their daily practice. "If [the therapist] is sincere, sensitive and open-minded in regard to himself as well as to the flier, he will instinctively take the right psychotherapeutic path," wrote Grinker and

Spiegel in an effort to reassure those with little or no previous experience in this area. But if sincerity and open-mindedness were the keys to effective psychotherapy, why limit its practice to a small number of highly paid professionals? "It is well," Grinker and Spiegel added as an afterthought, "if [the therapist] has a definite notion of precisely which path he is taking and how he means to accomplish his objective, which is to strengthen the ego in its struggle with anxiety."[93]

World War II was a moment of important professional transition for psychotherapeutic experts. It offered them the difficult challenge of proving they had something unique to offer at the same time that it offered them an unprecedented opportunity to try that something out on a new mass audience. Hampered by wartime shortages of time and staff and constrained by their own inexperience, clinicians tried to demonstrate that psychotherapy was delicate enough to require specialized skills yet not so delicate as to be confined to extreme cases of mental breakdown. Its benefits were palpable enough to merit the extension of psychotherapy to large numbers of people for many reasons in short periods of time, but only experts could achieve positive results. Amateurs, they warned, were prone to do terrible damage.

By normalizing the content and extending the subject of clinical expertise, the war redefined psychotherapy in remarkably expansive terms. According to psychiatrist Lawrence Kubie, a consultant to the Office of Scientific Research and Development and an ardent proponent of clinical emphasis on prevention, "psychotherapy embraces any effort to influence human thought or feeling or conduct, by precept or by example, by wit or humor, by exhortation or appeals to reason, by distraction or diversion, by rewards or punishments, by charity or social service, by education or by the contagion of another's spirit."[94] According to such definitions, virtually any human relationship could qualify as psycho-therapeutic. It is understandable that this drastic extension of psycho-therapeutic territory was confusing and failed to resolve outstanding questions about what alterations psychotherapy actually induced or who should be allowed to practice it. These controversial issues would consequently continue to be hotly debated throughout the postwar decades.

Their abilities as preventive emotional healers were matters of supreme belief among clinicians at the war's end. "As a result of our experience in the Army," William Menninger concluded with some satisfaction, "it is vividly apparent that psychiatry can and must play a much more

important role in the solution of health problems of the civilian." [95] It was an article of collective faith that psychotherapeutic treatment was reliable science, not hit-or-miss art. It brought "a systematic body of knowledge" to bear on wartime mental troubles with excellent practical results that were "more a matter of training than an accident of personality."[96] In part, clinicians were simply jumping on the same scientific and technological bandwagon that had proved so auspicious for other wartime experts. In part, their extreme therapeutic optimism resulted from the genuinely novel opportunities war had offered them: to minister to mass populations under conditions that forced them to renovate the conceptual and practical tools of their trade, meeting the immediate and urgent needs of ordinary people under extraordinary pressure.

For these and other reasons, the war produced a comprehensive reassessment of clinical terms. "Normal neurosis" became a conceivable clinical category only because the concepts of mental health and illness had themselves changed drastically, from qualifies inherent in or absent from individuals to a spectrum on which mental stability and instability were feats to be constantly achieved or avoided. Upbeat and hopeful, military clinicians had learned much about their own potential from their work with masses of ordinary soldiers. Not only could they treat cases of severe breakdown effectively, but they could prevent milder cases from deteriorating by intervening quickly and aggressively, nipping mental trouble in the bud. According to William Menninger, this reassessment was the war's most profound lesson, and it pointed very decidedly toward a larger jurisdiction for psychological experts.

If health is the concern of medicine, and if by mental health we mean satisfaction in life, efficiency, and social compatibility, then the principles of psychiatry must apply not only to each of us as individuals but to our social relationship with each other. The field of medicine must be recognized as inseparably linked to the social sciences and concerned with healthy adjustment of men, both individually and in groups.[97]

Under less strained conditions than war, he seemed to be suggesting, clinical experts could improve significantly on their very laudable military record. Psychiatrist Henry Brosin was even more explicit about what clinicians could do when the fighting ended and they applied the lessons of military experience to civilian life. "Good mental health or well-being is a commodity which can be created under favorable circumstances," he promised.[98]

In 1945 the mood of celebration among clinicians was the very same

that animated policy-oriented experts; so too were the doubts that lurked behind it. Surely the government and the public, grateful for clinicians' tireless, patriotic service, would see fit to ensure their future with generous infusions of training and research funds. Professional advance and the national interest were, in this case, fortuitously compatible and achievable through practical means. Postwar social order and stability rested on a foundation of mental health, a goal which was also, in Henry Brosin's terms, "a commodity." "National mental health," William Menninger concurred, "could be purchased if that were our aim."[99] This consensus that augmenting clinical funding was tantamount to improving national well-being would shortly be displayed on the floor of the U.S. Congress, where government officials debated the details of a federally sponsored mental health effort that became the National Mental Health Act of 1946.

If money for mental health were not forthcoming, how would the massive social problems, just waiting to be caused by untreated veterans, be managed? Clinicians predicted that men destabilized by their wartime experiences might be mentally mutilated for life if left to their own devices, victimized by a pitiful and expensive epidemic of "pensionitis" (a syndrome of debilitating dependence upon the state allegedly caused by financially rewarding veterans' mental instability), or prone to criminal temptations.[100] According to Daniel Blain, head of psychiatry for the Veterans Administration, the "ripples that emanate from each generating unit, each veteran, must not be vicious, antisocial, discouraging, hostilely aggressive. They must be kindly, warm, invigorating ripples that unite all of us."[101] Even mild ripples of maladjustment increased the likelihood that unemployment, illiteracy, strikes, illegitimacy, and racial prejudice (to name only the most frequently mentioned scourges) would mushroom in the postwar era. With sufficient clinical infrastructure, clinicians and their advocates pledged, the country could rest assured that undesirable social conflict would be minimized and veterans would be mentally prepared to live as economically productive and law-abiding citizens. In 1944 Alan Gregg put it as follows:

There will be applications far beyond your offices and your hospitals of the further knowledge you will gain, applications not only to patients with functional and organic disease, but to the human relations of normal people—in politics, national and international, between races, between capital and labor, in government, in family life, in education, in every form of human relationship,

whether between individuals or between groups. You will be concerned with optimum performance of human beings as civilized creatures.[102]

Behind this most ambitious vision of clinical responsibility for the general state of human civilization lay the same political uneasiness felt by policy-oriented experts. Clinical work, after all, had corroborated the growing body of nonclinical research demonstrating that democracy was seriously endangered by strong and unpredictable emotional currents, including ugly tendencies toward prejudice and conformity. By 1945 little or no sophisticated understanding was required to make the point psychoanalyst Franz Alexander had made ten months prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor: "It is no wonder that in the face of current world events one turns for explanation toward the psychiatrist, the specialist in irrational behavior."[103]

The course of the war had borne out the truth of Alexander's view that "the real difficulties of democracy ... are emotional."[104] Clinicians' daily responsibilities for shoring up soldiers' morale and group cohesion had taught them that reason could never compete with emotion when human motivation and behavior were involved. Primitive fears and immediate loyalties had done far more to keep the fighting forces fighting than had campaigns (most of them miserable failures) to persuade soldiers that preserving democracy and eradicating fascism were worth the highest sacrifice.

Demoralizing as this wartime lesson was, it hardly lowered the aspirations of clinicians, the most forward-looking of whom had predicted that "the day will come when [the] Cinderella of Medicine, Psychiatry, will be honored as a wise and bountiful Social Princess dispensing a largess of culture."[105] The daunting lessons of war merely fueled their missionary vision. What were clinicians if not experts in emotional management? And was not a plan of conscious, emotional management democracy's best hope for survival? By the end of the war, most clinicians certainly thought of their professional obligations in the activist, liberal terms articulated so well by figures such as William Menninger, Harry Stack Sullivan, and Alan Gregg. They considered themselves custodians of a vital social resource—mental health—without which economic prosperity, democratic decision making, and intergroup harmony were implausible, perhaps impossible.

Although they could not have known it at the time, their future role as emotional managers was as fraught with political contradictions as

was that of their counterparts who imagined themselves as the enlightened social engineers of postwar society. To champion the individual in the process of striving toward psychological insight, as they did, and to insist that the essence and future of democracy lay in this momentous struggle, as they also did, was the historic task of those experts with a unique understanding of the human personality. Lawrence K. Frank, who had proposed before the war that society be treated as a "patient," was equally prophetic when he wrote in 1940,

We are, somewhat reluctantly, realizing that the democratic aspirations cannot be realized nor adequately expressed in and by voting and representative government; democracy, or the democratic faith, is being reformulated today in terms of the value and integrity of the individual, not as a tool or as a means, but as an end or goal for whose conservation and fulfillment social life must be reoriented.... Thus freedom for the personality may be viewed as the crucial issue of a democratic society, for which we must seek to develop individuals who can accept all the inhibitions and requirements necessary to group life, without these distortions and coercive, affective reactions.[106]

Ringing defenses of democracy, converted into psychological rhetoric such as "freedom for the personality," were not the inherently liberating manifestos that Frank and most other World War II-era clinicians believed them to be. They were politically ambiguous. Labeling the individual precious and dignified was certainly nothing new in U.S. history. Calling for direct control of the psychological terrain—because it was the only effective means of safeguarding democratic potential and averting a menacing epidemic of blind conformity and authoritarianism—was new, at least as an explicit public ideal and purpose of government. World War II had shown that experts would have to manufacture democratic personalities because U.S. social institutions had failed to produce people who could be trusted with democracy's future.

Thus were the clinical hopes and dreams of prevention that emerged from the war based on a collapse of faith in the rational appeal and workability of democratic ideology and behavior. Some clinicians dedicated to shoring up the emotional basis of democracy in the postwar era (humanistic theorists and practitioners, for example) did so by consecrating the individual psyche as the ultimate source of value and turning self-regulation into an act as publicly virtuous as it was personally meaningful. Others (behaviorist theorists and practitioners, for example) dismissed such psychological individualism as a foolish dream and insisted that only scientific expertise could be trusted as an incorruptible source of authority and control. Humanists wanted to actualize the per-

fect self. Behaviorists were more modest; they merely wanted to condition good behavior.

In spite of important tactical differences between clinical schools and tendencies, the postwar era they all envisioned was founded on the professionally unified project that emerged from World War II: to enlarge psychology's jurisdiction. As we shall see later, in chapter 9, important developments after 1945 grew out of the fundamental clinical lessons of world war. Clinical theory had to be grounded in normal psychology. Clinical services had to reach masses of ordinary people, coordinated and delivered by the state if necessary, so that normal neuroses could be treated before reaching a point that threatened social stability. And because human motivation brimmed with irrationality and resisted so stubbornly the call of reason, clinical experts would be indispensable guides in an era of social and emotional reconstruction. Democratic personalities would have to be remade from the inside out.