What the Thunder Said

for Jérôme Rimbert

Fulgur Conditum , the inscription reads: [Here] lightning [has been] buried. Altars, stone tablets, commemorative markers bearing that same terse inscription are still occasionally discovered on the barren, wind-blown plateaus of rural Provence. For wherever lightning strikes (drawn, no doubt, by a high level of electromagnetism) there's a likelihood that the Gallo-Roman rites of thunderbolt burial were once practiced. Considered sacred (sacer ), as the very signature of Jupiter himself, lightning was "interred" at the exact point at which it fell. Along with the lightning bolt were buried whatever bits of wood, roof tile, etc. (dispersos fulminus ignes ), that might have burnt in its passage. A small cylindrical retaining wall (a puteal ) was erected around the point itself, the above-mentioned epigraph affixed, an animal (usually a sheep, a bidens ) sacrificed in expiation, and the enclosed ground consecrated by an officiating priest. This priest, a fulguratore , was fully initiated in the art of lightning worship. The ritual itself was immediately followed by an interdiction:

Gallo-Roman altar bearing the inscription Fulgur

conditum: Here lightning has been buried.

Photo by the author.

no one, henceforth, could approach the consecrated area nor gaze upon it from a distance. For it had now become the inviolable territory of Iupiter Fulgerator himself.

The Roman poet, Lucan, has left eloquent testimony to such a ritual. Arrus, we may assume, was the officiating priest in this particular instance:

Arrus gathered together the lightning's scattered fires,

Buried them in murmuring dark formula,

Placing the site, thereby, under divine protection.[1]

These ceremonies, or exhortio , were aimed at eliminating any destructive forces still inherent within the thunderbolt itself, while preserving its sacred character in the shafts of the consecrated earthen wells. Lightning, as divine manifestation, was thus secured within a context of strict sacerdotal observation: its holy fires were ritually "housed."

From classical sources, we have abundant evidence of the awe that these forked fires once inspired. Plutarch, for instance, tells us that whoever happened to be touched by lightning was considered invested with divine powers, whereas anyone slain by one of its jagged bolts was deemed equal to the gods themselves.[2] Furthermore, it was believed that the bodies of those struck dead by lightning weren't subject to decomposition, for their innards had been embalmed by nothing less than celestial fire.

Ultimate nexus between heaven and earth, the lightning bolt has a mythopoeic history that can be traced as far back as the Assyrians. They considered its sacred fire not so much an attribute of their divinity, Bin, as his very manifestation. The same would hold true for the Phoenicians, the Egyptians, and the Cypriots. It is not until the cult of lightning reaches Greece, transmitted no doubt by those pre-Hellenic people, the Palasgi, that the lightning bolt as divine manifestation becomes sema , sign, the personal attribute of an otherwise invisible deity whose reign would now extend over all atmospheric phenomena: Zeus Keraunos.

Undergoing continual changes within Greece itself, lightning worship would reach Rome through the mediation—call it the divinatory agency—of

Etruscan priests. Indeed, these priests, the fulguratores , armed with their notorious libri fulgurales (oracular books in which questions were posed in archaic Latin and answered by these mediators in Etruscan) dominated the Roman cult of lightning worship until the end of the Roman Empire. Even the original Italic figure of Jupiter, thunderbolt in hand, underwent a certain "Etruscification." Originally considered a sky spirit (a numen ) in archaic Roman mythology, he takes on the epithets optimus and maximus under the spiritual tutelage of these mediating Etruscan haruspices. A magnificent temple in his honor was erected on the pinnacle of the Capitoline, commissioned, no doubt, by Tarquinius Priscus and Tarquinius Superbus, the semilegendary twin kings of Rome, reputedly Etruscan themselves. There, the effigy of Jupiter was flanked on either side by the goddesses Juno and Minerva, forming a triadic divinity thoroughly Greco-Etruscan in inspiration.

Whether we're considering this original Italic spirit reigning over all things atmospheric, his elevation to Jupiter Optimus Maximus upon the pantheon of the Capitoline or, much later, one of his Gallo-Roman variants here in the distant hills of Provence, we discover that Jupiter may be identified by two opposing characteristics. The first is evident enough: Jupiter, unfailingly, bears the thunderbolt. Be he Iupiter Fulminator casting the bolt itself, Iupiter Fulgerator revealing himself in its very flash, or Iupiter Tonans declaring his presence in a roll of thunder, he wields, in every instance, that celestial fire. There's a second characteristic, however, that lies as if secreted within the first. As with virtually all archaic representations, characteristics invariably come paired in antithetical sets. The evident conceals the covert, the manifest, the obscure. Modern studies in ethnology, linguistics, and other related disciplines have made us increasingly aware of this particular phenomenon. In 1910 Freud was already writing in regard to words: " . . . it is in the 'oldest roots' that the

antithetical double meaning is to be observed. Then in the further course of its development, these double meanings [tend to] disappear." Same, too, Freud continues, with the "archaic character of thought-expression [found] in dreams."[3] In tracing the etymological origin of a particular word ourselves, how often we'll fall upon one of these antitheses, as if the word itself was embodying, at its very inception, a paired set of opposing signifiers.

In a relatively rare epigrammatic discovery, a Gallo-Roman altar unearthed near Aix-en-Provence bears the inscription Iovo Frugifero : that is, Iupiter Frugifer. Signifying fertility, fecundity, the instigator of harvest, it would appear at first as an epithet signifying an entirely different divinity. How do we get from Fulgerator to Frugifer , from Jupiter wielding lightning, to Jupiter bearing fruit? Obviously, lightning brings rain, and rain, fertility, but how do these two separate, sequential events find shelter within a single all-encompassing vocable? The entire question lies there.

Turning to Roman folk mythology for support, we learn that Jupiter, as the supreme divinity, was celebrated throughout the year not only as master of lightning but also as protector of crops.[4] The Feriae Jovis , festivities dedicated to Jupiter, honored the guardian of the vineyard, the grape harvest, and the winepress. From the Vinalia priora in spring to the Meditrinalia in autumn, Jupiter was invoked at every crucial moment in the vintner's calendar. It was unto Jupiter that wine was offered, rendered, consumed. Other Feriae Jovis that might be mentioned in regard to Jupiter's "parallel identity" include the Robigalia and Floralia of spring. Both of these festivities served as propitiatory rites in favor of the young grain: the first as a protection against blight, the second as a stimulation or encouragement to the kernel itself. Here, once again, Jupiter, master of the heavens, was the ultimate mediator in matters strictly terrestrial, agrarian.

A sculpture discovered in one of Rome's distant colonies in North Africa (near present-day Zaghouan, Tunisia) depicts Jupiter bearing in one hand the inevitable thunderbolt, while in the other, instead of the traditional scepter, a cornucopia filled with fruit. With this sculpture, we have a perfect iconographic representation of the god in all his archaic ambivalence. Both fulguration and fructification find themselves depicted within a single homogenous statement. Together, one and the other are brought to coalesce.

How does Jupiter accumulate, or should we say incorporate, such powers? A line from Pliny's Naturalis historia might help elucidate the deliberately maintained ambivalence of these twin attributes. Pliny, describing the libri fulgurales , writes that the Etruscan fulguratores , charged with all matters pertaining to lightning—be it its observation (observatio ), interpretation (interpretatio ) or propitiation (exhortio )—believed that the lightning bolt itself penetrated the earth to a depth of five feet.[5] This remark is not as insignificant as it may appear. For it tells us that lightning, in the eyes of those mediating Etruscan priests, didn't simply strike and consequently ground itself against the surface of the earth: it actually entered, penetrated the earth as its recipient body. In the language of Eliade, we're in the presence, here, of an "antique hierogamy." Between Jupiter, the "Celestial Thunder God," and Jupiter, the "Bearer of Fruit," we might well be witnesses to that archaic ambivalence mentioned above—that deep-seated androgyny—wherein the god incorporates the qualities of both fructifier and fructified, inseminator and inseminated. Soon, these very qualities will undergo separation. Jupiter will retain his thunderbolt, but an ubiquitous earth-mother will come to reassert her place as the bearer of all earthly goods. Soon, each will be assigned separate, complementary roles in this evolving mythology, this coital enactment "indispensable to the very energies which assure bio-cosmic fertility."[6]

Discussing one of the many engraved inscriptions bearing the words Fulgur Conditum , the late Marcel Leglay made the following pertinent remark:

If lightning is buried with so much care and precaution, its sacred stones deposited beneath an earthen mound that's ringed, in turn, by a boundary wall, and the locus altogether consecrated, is it only for the sake of self-protection? For neutralizing the effects of the lightning bolt? For observing, in short, a taboo? It wouldn't seem so. In my opinion, it's more for the sake of preserving, preciously safeguarding in situ , the source of both the inception and diffusion of that terrestrial fire. The source, indeed, of life itself.[7]

More than fortuitous points of momentary impact, these "wells" of celestial penetration needed to be circumscribed, the divine fire that they'd introduced retained within the entrails of the earth itself. Out of this encounter, all things living, ineluctably, would spring.

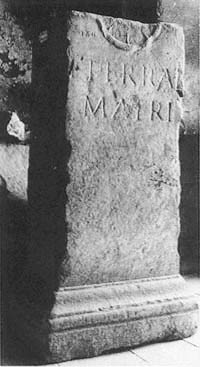

By way of illustration, we only need examine a relatively nondescript limestone altar discovered in the region of Nîmes. Here, the two-word inscription, rather than reading Fulgur Conditum , commemorates in stately Roman capitals Terra Matri . Just over this inscription lies engraved the truncated half of a wheel. The emblem of the Celtic god Taranis, this wheel designates thunder. As Jupiter's Celtic counterpart within that widespread family of Indo-European divinities, Taranis's attribute isn't the lightning bolt, but its sonorous aftermath, the hollow thunderclap. The wheel, in the roar of its iron hoop over cobbles, serves as a perfect mimetic signifier. Even Taranis's name, drawn directly from the Celtic root, tarans , designates nothing less than thunder itself. Together, we have, reunited in that simple, somewhat austere altar, the two fundamental protagonists in this cosmic drama: heaven and earth; fire and the ground it fecundates; celestial father and the now distinct terrestrial mother, represented in pure symbiosis.

The wheel, attribute of the Celtic thunder

god Taranis, represented in direct relation

to Mother Earth, Terra Matri.

Photo by the author.

Dedicated to those two indissociable forces, the altar helps clarify the meaning of the Gallo-Roman cult of lightning worship. Clearly enough, the burial of that celestial fire was a means of conserving its procreant energies within the sacred interiors of the earth itself. In a dialectic of opposites, the altar celebrates the indispensability of each within the cosmic contextuality of

both. Furthermore, it tells us, in no more than two words and a single iconographic device, exactly "what the thunder said."

In the high barren wastelands of the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, lightning continues to fall in the same areas where Gallo-Roman Fulgur Conditum inscriptions are still occasionally discovered. These discoveries aren't fortuitous. Despite the popular dictum, lightning not only strikes twice, it strikes the same location repeatedly if that location happens to be, as here, on raised ground and rich in ferromagnetic deposits. Lightning, in these parts, falls frequently. And if, in the past two thousand years, its "entry" no longer receives the kind of consecration it once enjoyed from the hands of officiating fulguratores , we might consider, at least, yet another form of reception. For lightning, the sheer, unmitigated experience of lightning, continues to provoke in the subsoils of our own psyche an inexpungible sense of awe. Devoid now of all ritual, the sublimating effects of all mythopoeic projection, it continues to arouse, nonetheless, the kind of dread and reverence that's always been its due. Ambivalent, provocative, it goes on striking at our deepest, most dormant levels of consciousness. Yes, lightning keeps falling. And its fires, perforating the frail armor of late postmodern rationality, continue to instill, enlighten. Continue to nourish the most fertile regions of our imagination with so many successive bolts of pure, unprogrammed luminosity.