8—

About-Face

The Narmer Palette (Fig. 38) refuses and replaces as much as it repeats and revises the chain of replications of late prehistoric image making. On the one hand it replicates the narrative images on the Oxford, Hunter's, and Battlefield Palettes (Figs. 26, 28, 33); it has thoroughly assimilated late prehistoric image making. But on the other hand it revises some of the general conditions of intelligibility of late prehistoric images, conditions that had established them as disjunctive replications of a common pictorial metaphorics and narrativity.

A Link in the Chains

The ambiguity in the Narmer Palette—in itself appearing to be an effort to control the ambiguity of late prehistoric image making—makes the image on the palette difficult to understand. In principle it could be interpreted as a replication within two different chains—namely, that of late prehistoric image making and that of the subsequent tradition—the palette being an early, if not the earliest, replication in what would emerge in the next two hundred or more years as the canonical tradition (for First and Second Dynasty work, see Davis 1989: 159–71, 179–89). Neither placement of the image in its "serial position" in an art history (Kubler 1962) would be incorrect, but neither is complete or sufficient. While it does revise the late prehistoric chain of replications, it would have to be replicated in and for itself—a chain of replications occurring only after the Narmer Palette had been made and necessarily assuming it—for this revision to achieve the status of an alternative tradition. The replication of the revision transforms it into the conditions of intelligibility on which a coherent, if always necessarily disjunctive, iconography can be founded; thus we

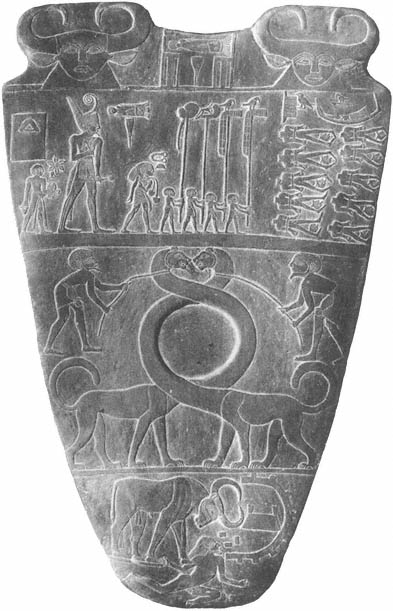

Fig. 38.

Narmer palette: carved schist cosmetic palette from Main

Deposit at Hierakonpolis, early First Dynasty.

Courtesy Cairo Museum.

can say not that the Narmer Palette performs this transformation for itself but that later images do so retroactively by replicating it. Our difficulty in understanding the image, however, is attributable not only to its peculiar place in the chains of late prehistoric and canonical image making; it is also possible that the narrative on the palette did not fully amount to an image, for its composition as an image in both the late prehistoric and the canonical chains of replication is seriously disturbed.

On typological grounds the Narmer Palette is usually assigned by Egyptologists to the Horizon A /B or early First Dynasty—that is, to the shadowy era of the synthesis of late prehistoric polities in a dynastic state ultimately ruled by national monarchs (see Trigger 1983; Kemp 1989). Narmer himself seems to have been one of these kings; his name appears in various other contexts (see Edwards 1972: 1–15; the stela from Tomb BIO at Abydos, attributed by Petrie [1900–1901: 1, pl. 13, no. 158] to Narmer, is now thought to belong to King Hor-Aha at the beginning of the historical First Dynasty [Kaiser and Dreyer 1982: 213–191]). It is unlikely, however, that the historical Narmer was solely responsible for the so-called unification of all Egypt, and if the palette must be regarded as a representation of real historical events—at best this would be a partial interpretation of its metaphorical and narrative structure—it could recount a local conflict, for example, between "Narmer" and neighbors to the immediate north or south. The simplest historical interpretation puts the Narmer Palette later in an absolute chronology than the other palettes examined here and defines it as the type of representation appropriate to the interests of the emerging state.

Like the canonical tradition of image making, the national dynastic state cannot have emerged all at once. Pre- or nonstate image making would have continued to exist, at the same time state-affiliated images were being produced, in different centers of social life—for example, in small villages, in regional polities not yet absorbed into and possibly even resisting nationalization, or among competing elites. Thus the Battlefield Palette (Fig. 33) and the Narmer Palette could be regarded as contemporary—on typological and stylistic grounds, this is perfectly possible—although they were conceived in different ways. For expository convenience we can regard the Narmer Palette as later

than the other images and as belonging to a different social and cultural formation, but we do not yet know how one merged into another. The Narmer Palette is itself part of the evidence for this process.

From Before to After:

Replicating Late Prehistoric Representation

The top edges of both sides of the Narmer Palette are decorated with frontal heads of bovids, two on each side, possibly depicting one of the cow goddesses, Hathor or Bat, of later mythology (Vandier 1952: 596; see also Baumgartel 1960:91). There is nothing to justify the anachronistic parallel, or indeed the supposition that the bovids are female (although according to the anachronistic interpretation Hathor, as female, should be represented without a beard). It is more consistent with the general narrative metaphorics of the entire palette to take the heads as human-faced bulls. Like the ruler's force "as a lion" on the Battlefield Palette, the ruler's power "as a bull" is figured within the pictorial text: on the obverse bottom, a great bull attacks an enemy's citadel, and on the reverse middle the ruler, smiting his enemy, is depicted wearing a bull's tail in a handle ranging from his belt, decorated also with four bulls' heads—possibly to match the four at the top of the palette—affixed to what appear to be strips of beaded cloth. Although subtle differences among the four heads on the top of the palette have often been remarked, it is unclear how these might be reconstructed in the image as a whole; perhaps they are merely variations in textual morphology that do not bear on the metaphorics. The heads flank a palace facade (serekh ) containing the nar -fish (a species of catfish) and mer -chisel, signs placed also before the largest figure in the obverse top zone, apparently naming the ruler himself. The entire decorated top edge of the palette is sometimes interpreted as depicting a roof or canopy for a facade with bucrania; although not necessary for our purposes, this reading accords with other features of the image.

Below the decorated top edge, set off by a thin register line, the two sides of the palette are divided into three horizontal zones. Except for the "rebus"

(on the reverse top right), each zone on the Narmer Palette containing a representation of the ruler has a register ground line—namely, the obverse top, with the ruler and his retainers inspecting the corpses of ten defeated enemies; the obverse middle, with the ruler's two retainers mastering two serpopards; the obverse bottom, with the ruler-as-bull vanquishing an enemy; and the reverse middle, with the ruler smiting his enemy. By contrast, ground lines do not underscore enemy figures at the obverse top right, the obverse bottom, and the reverse bottom. In each of these zones the enemies are depicted as defeated, twisted on and from their baselines and upright axes, an image presented in another way on the Battlefield Palette. The special place of the enemy on the ruler's ground line in the reverse middle zone will concern us later. The registers therefore mark the different status of figures within the image as being either associated or not associated with the ruler. Thus the Narmer Palette proffers the latest version of the animals' and the hunters' differing grounds on the Hunter's Palette; moreover, as on the Battlefield Palette, the animal enemies of the hunters have become the human enemies of the ruler. In addition to marking and maintaining distinctions indicated in earlier images in the chain of replications, however, the registers on the Narmer Palette divide each zone from the others on that side of the Palette. As elements of composition, passages of visual text, they separate the zones—and thus presumably the elements of the story—in a way that is not presented on the late prehistoric images we have examined so far.

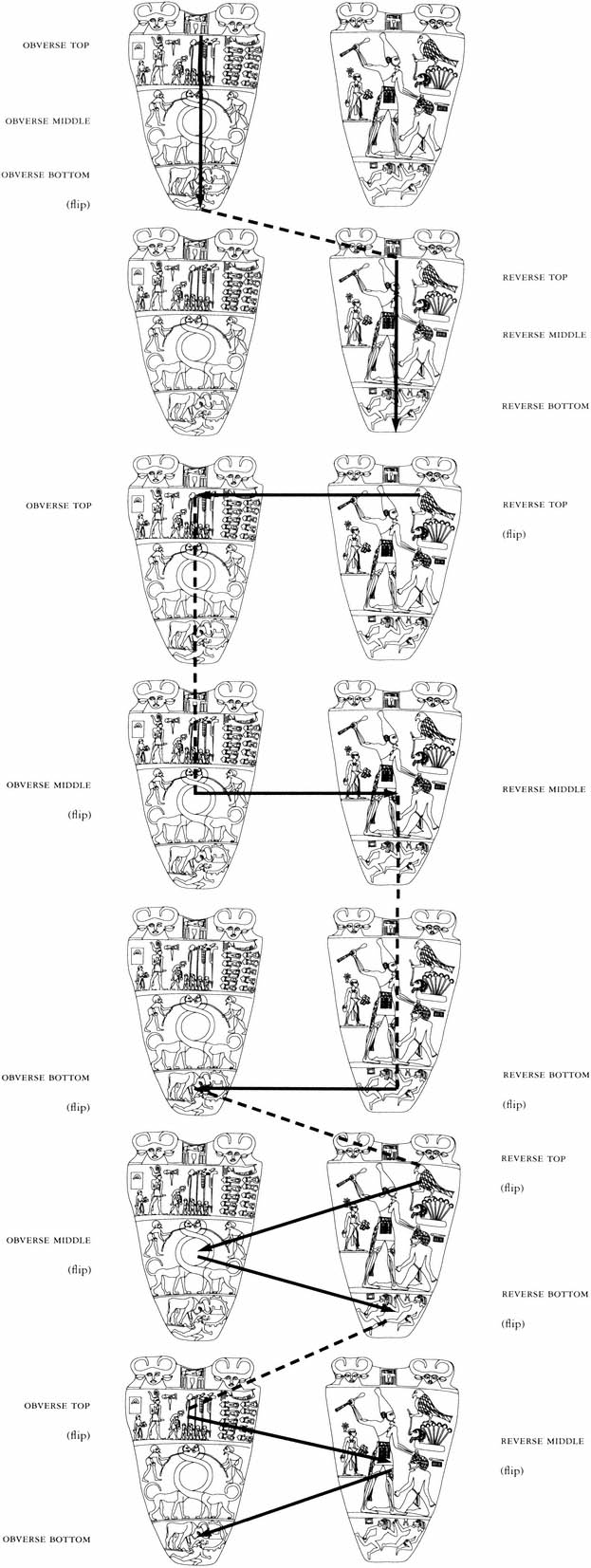

A viewer whose visual culture included the chain of replications of late prehistoric representation would presumably seek to interpret the Narmer Palette in the same way the Oxford, Hunter's, and Battlefield Palettes (Figs. 26, 28, 33) would have been viewed—that is, as a narrative image. Accordingly, on the Narmer Palette (Fig. 39) each side presents a zone depicting what comes after (at the top) and what precedes (at the bottom) the ruler's decisive blow of victory, with the obverse depicting its aftermath and the reverse its preconditions. The story is therefore arranged in the four top and bottom zones of the palette, top-to-bottom/obverse-to-reverse! as consistently after-to-before.[1] The pictorial text, however, also includes elements relating material in the other temporal direction, from before to after (strictly speaking, a counternarrative),

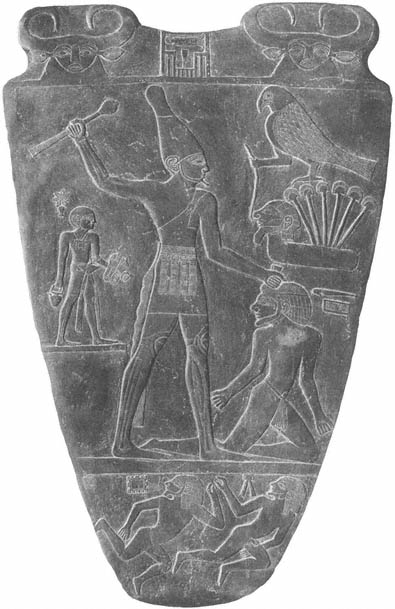

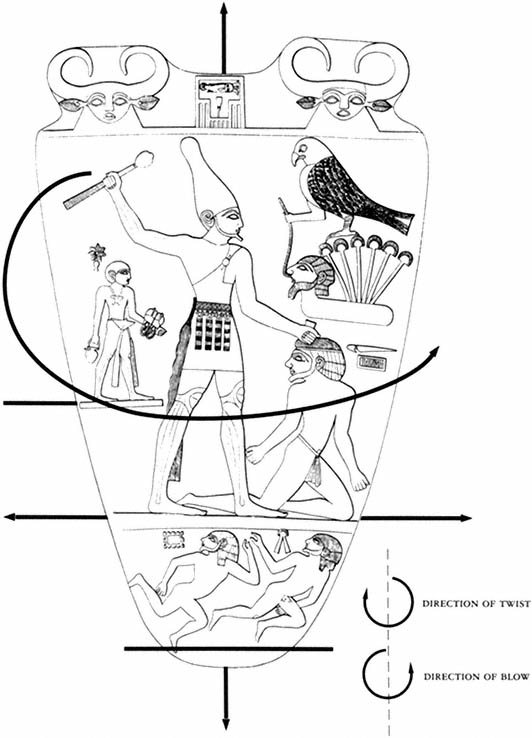

Fig. 39.

The structure of the narrative image on the Narmer Palette.

as well as elements resisting or breaking out of the narrative sequencing altogether. In view of this complexity it is useful to go through the zones one by one before considering their metaphorical and narrative interrelations.

Beginning with the obverse top, the victorious ruler, wearing the Red Crown (it would later signify Lower Egypt, but we cannot necessarily assume this denotation here) and labeled with the two hieroglyphs of his name, is preceded by four standard bearers. He is flanked on the left by his sandal (and seal?) bearer and on the right by a figure most commentators have identified as a "priest" carrying scribal equipment. Carrying the seal's case(?) around his neck and the sandals of the ruler, presumably strapped to his wrist, the sandal bearer is labeled with a rosette and pendant plantlike form. The image on the ruler's seal is apparently depicted above the sandal bearer to the left in the upper left

corner of the zone. Although its status as a seal imprint has not been recognized, the central form in this sign has been tentatively identified as the "reed float" used by Old Kingdom sportsmen to hunt hippopotami (see Baumgartel 1960: 92–93) or the "bilobate Khons sign" (Williams and Logan 1987: 248, note 13); more likely it is a schematic depiction of the ruler's sandals with the strap the sandal bearer uses to carry them around his wrist (see Vandier 1952: 596). The "priest" is labeled with a rope noose or tether and a loaf. There are reasons to suppose that these two personages have special narrative significance; it is even possible to interpret them as members of the ruler's family. The entire group of the ruler and his followers inspect two rows of five decapitated enemies spread on the ground (without ground lines) at right angles to the progress of the victors. The several signs or hieroglyphs placed above this group may or may not be read like later hieroglyphs. One depicts a door on its pivot; it could be taken as the hieroglyph "great door" (= wr -swallow + door; the bird is to the right of the door)—for example, the door of the temple where the palette may have been dedicated or the door of the palace before which the enemies are displayed. Another depicts a falcon, possibly denoting the ruler, carrying or surmounting a harpoon, probably denoting the enemy shown on the reverse of the palette, where he is labeled (with this sign and a sign depicting a pool of water) as "harpoon" or "coming from harpoon territory," presumably a swampy or marshy region. (In both contexts in the pictorial text, the harpoonlike sign is difficult to decipher; the object may be one of the smaller implements—such as bone and ivory pins or hooks—commonly found in predynastic funerary assemblages. For convenience, the label "harpoon" is used here.) A third depicts the "sacred bark" of the ruler. (For possible readings of these signs, see Kaplony 1966; Williams and Logan 1987.) Considering that the obverse top of such images has so far always been constituted as the beginning of the narrative text, the first pictorial text encountered on the Narmer Palette, then, concerns the achievement of the king, the celebration of his victory.

What precedes this episode is related in the top zone on the reverse side of the palette. Here a rebus depicts the enemy or enemies brought to the ruler by a falcon—an aspect, double, or representation of the ruler or perhaps his divine protector. The falcon inserts a hooked cord into an enemy's nose, possibly to

prepare him for the beheading whose aftermath is related in the obverse top zone, where the king inspects decapitated corpses. It is sometimes said that the six stalks of papyrus growing from the enemy's body—treated abstractly and looking like the later hieroglyph for swampy or watered land—signify "six thousand [enemies]," on the basis of a presumed parallel between the papyrus and the lotus hieroglyph (= numeral 1,000), but there seems to be little justification for the equation. Instead, the papyrus may denote the enemy's home territory, Papyrus Land (Vandier 1952: 596). However it should be interpreted, the rebus indicates in a general sense that the ruler—in his aspect as (or with the protection of) Falcon—has defeated his enemies and prepares them for their judgment or destruction.

Continuing the progression backward through the narrative chronology, the scene preceding this one appears on the obverse bottom, where a bull uses its horns to break down the walls of a fortress evidently inhabited by the enemies, one of whom is thrown to the ground, facing away from the bull, and trampled. Like the falcon on the reverse and like the lion on the Battlefield Palette (compare also the bulls on the Louvre Bull Palette, Fig. 37), the bull can be taken as an aspect, double, or representation of the ruler, although he should not be identified with the ruler's human person as such. Within the encircling outer walls of the fortress is a smaller structure with two towerlike sides; it might be equivalent to the sign used to label the right enemy in the reverse bottom zone, which probably depicts a cattle pen or storehouse, but because of its size might indicate the enemy leader's residence. Three small squares in front of the fallen enemy's face and below Bull's horns are difficult to interpret. They may represent fragments of the walls of the fortress broken down by Bull; on the Libyan or Booty Palette (Fig. 53), probably produced as a replication of the Narmer Palette or similar images, they resemble small rectangular houses within the walled towns. This zone seems to depict the moment in the battle when the enemies' defeat was secured. In his aspect as (or with the protection of) Bull, the ruler enters their citadel.

Finally, what comes before this episode is related on the reverse bottom; in the Narmer Palette's sequencing of the episodes of its narrative, the chronological and causal beginning "concludes" the text. Here two enemies are depicted

as fleeing toward the right, that is (returning through the text to the preceding stage, on the obverse bottom), toward the citadel in which they will take refuge to no avail. They look back over their shoulders as if being pursued by the ruler. Although the ruler does not appear in the pictorial text of this zone of the image, the larger text is clear about his presence; the viewer already knows (having seen the obverse bottom) that Bull will break down the enemies' citadel, a building the text had depicted as a broken version of the sign here used beside the left enemy figure to label him. Furthermore, the enemies' glances over their shoulders are directed upward to the figure of the ruler smiting his enemy presented immediately above this zone. Although coming last in the image as it would be viewed in the context of existing late prehistoric representation, at the very bottom of the reverse side of the palette, the narrative "begins," then, with the ruler pursuing his enemy.

Almost all commentators agree that the sign for the left enemy on the reverse bottom depicts or denotes a fortress with bastions. Werner Kaiser (1964: 90) took it specifically to name the northern town of Memphis, presumably, at this period in protodynastic history, an enemy of the Upper Egyptian polity in or for which the Narmer Palette is usually thought to have been made. (This latter assumption is based on the fact that the principal figure of the ruler in the image, in the reverse middle zone, wears the White Crown, in later iconography the symbol of Upper Egypt; that the palette was found at Hierakonpolis in Upper Egypt might be taken as supporting evidence, although the context speaks only to the final deposit of the palette and not to its manufacture and use.) The sign for the right enemy was interpreted by Yigael Yadin (1955) as depicting a "desert kite," a fortified enclosure used by much later desert herders in Transjordan to protect their flocks. (While kites might have existed in prehistoric times, there is no archaeological evidence for them [see Ward 1969: 209]; more likely the structure had a more all-purpose status as a farm building or storage house.) Yadin's reading led him to see the enemies on the Narmer Palette as Western Asiatics and the entire palette as documenting an Egyptian invasion of southern Canaan-an interpretation that could be sustained even if we reject his reading of the sign. (Alternatively, Kaiser read the sign for the right enemy tentatively as denoting the delta town of Saïs, presumably a twin

of "Fortress," or Memphis, in its struggle with Upper Egypt; other readings have also been proposed [see Kaplony 1966: 159, note 190]. It could be a depiction of the knotting of the loincloth worn by the enemy in the reverse middle zone.) If all three signs labeling the enemies on the Narmer Palette, in the obverse and reverse bottom zones, refer to their actual hometowns, then, in Kaiser's (1964) view, the palette could document a contest between Narmer of Upper Egypt and an eastern delta coalition in which the principal enemy, Buto, or the "harpoon" enemy on the reverse middle (Newberry 1908; Vandier 1952: 596; Kaiser 1964: 90), was assisted by Memphis and Saïs.

But I question the wisdom of forcing the Narmer Palette into serving as a document for actual historical events, and of "reading" its images and signs chiefly on the basis of anachronistic parallels with the meanings of particular hieroglyphs in Middle Egyptian script, in order to reconstruct it as an annalistic or commemorative "statement," somewhat like later kings' chronicles, of Narmer's victory. (Some of the signs on the palette have parallels in Archaic Egyptian script, but the denotations of many of these signs are not definitively known and they largely postdate the Narmer Palette. "Reading" the Narmer Palette's signs as hieroglyphs could be greatly elaborated; only a small selection of the possibilities have been noted here.) In some cases the signs certainly have replications in hieroglyphic script, which could be seen precisely as evolving from late prehistoric pictorial narrativity as it is replicated and revised on the Narmer Palette; the palette is complex precisely because it can sustain interpretation in terms of both late prehistoric image making and later canonical representation. But historical method dictates that we interpret it according to the former, the conditions of legibility apparently assumed or accepted by its original maker and viewers, rather than the latter, a mode of intelligibility not completely constructed until the Third Dynasty at the earliest, a full two hundred years later. Moreover, neither a "decipherment" of some of the images and signs on the Narmer Palette as (later) hieroglyphs nor an interpretation of the image as documenting historical events can, in itself, allow us to grasp the scene of representation in which this ostensibly annalistic and documentary statement was produced.[2] For example, even if specific references for the image were found in actual events, they alone could not explain their representation

metaphorically or narratively in the image as such; the scene contains much more than the literal denotation—whether depictive or hieroglyphic—of individual figures, motifs, and signs. For example, to represent or recount the contest and defeat of the enemies, the maker of the Narmer Palette replicated a motif, the ruler "smiting," that had been produced in other historical contexts of replication presumably different from the context of the "wars of unification" and well before even the most preliminary formation of script—namely, the conflict scene depicted in the Decorated Tomb painting at Hierakonpolis (Fig. 5) some 250 years earlier than the palette. Again, in deciding to use Bull to stand for the ruler, the maker was influenced in the chain of replications by earlier or other representations of the ruler in the aspect of a great animal. His choices in replicating the existing metaphorics of "looking backward" date to the Oxford Palette at least. In all these cases the meaning of figures, motifs, and signs on the Narmer Palette must have derived, in context, from this earlier history of signification; an appeal to the later meaning of the images—in hieroglyphic script or canonical art—besides being unnecessary, is likely to ignore the inherent structure of disjunction in the replication of symbol systems.

For the moment, then, it is best to leave open the question of the specific denotation of the signs labeling the enemies; we can take them as generic labels for a "harpoon" enemy and two others, "fortress" enemy and "desert-kite" (or "knot") enemy, all of which could have had a symbolic or metaphorical as well as a literal significance for contemporary viewers. Whether the ruler, in his battle with "Harpoon," "Fortress," and "Desert Kite," is conquering new territory, suppressing a revolt, or carrying out some other action is difficult to determine (although many commentators would take the image to denote the territorial expansion of the Upper Egyptian polity, whether to the north or to the south, in the so-called unification of Egypt). The pictorial mechanics of the image—independent of any "meaning," probably irretrievable, it might have had for certain viewers—probably require only that the ruler's activity be construed as a victory with certain particular symbolic features. In fact, it was precisely because a metaphorical and narrative system of representation had evolved in the chain of replications of late prehistoric image making that any

particular activity of any individual ruler could be rendered intelligible to viewers. Whether or not episodes of actual conflict that had taken place or were taking place at the time the image was made sustained interest in the replication, the visual text could be replicated in later image making with or without reference to the "real" denotanda of any particular, individual replicatory version. (For the continued replication of the "smiting" motif in canonical image making, see Davis 1989: 64–68; Hall 1989.)

Being throughout

If we invert the order of their arrangement in the image, the four episodes presented in the four top and bottom zones of the Narmer Palette can be reconstituted as a narrative chronology with an implied causal armature (Fig. 40). I label them as Episodes One through Four, going from the implied causal beginning to the implied ending:

|

Although the direct blow of the ruler is not literally presented in any of the relevant passages of depiction, it links each of the episodes in the story chronologically and causally to the next. Reading from the "beginning" of the narrative (presented at the "end" of the pictorial text), the ruler must—between the first two episodes of the story—successfully track the fleeing enemies, locate their citadel, and scale or undermine its walls; we are shown the enemies fleeing (Episode One) and the citadel, already taken, with the enemies being trampled (Episode Two). Between the second and third episodes of the story, the ruler or his army must round up the conquered inhabitants and prepare them for judgment and imprisonment; we are shown the town being overrun just after the walls have been demolished (Episode Two) and Falcon mastering the captives taken (Episode Three). Between the third and fourth episodes of the story, the

Fig. 40.

Four episodes in the fabula of the narrative on the Narmer Palette.

ruler or his executioners must lop off the heads of the enemies condemned to die or to be sacrificed in the victory ceremonials; we are shown Falcon lifting an enemy's head (Episode Three) and the ruler inspecting the decapitated corpses (Episode Four).

The ruler's decisive blow must occur, then, several times in the narrative. Indeed, it animates the narrative chronology and causality (in narratological jargon, the fabula), for it is the transition, the event or process, that takes the story inexorably from one state of affairs to another. (Readers unfamiliar with the narratological concepts fabula, story, and text may wish to consult the Appendix before reading further.) When the viewer flips the palette from obverse top, where the text "begins," to reverse top (that is, goes from Episode Four to Episode Three), despite the logical progression to the rebus in the reverse top zone, the most prominent feature occupies the reverse middle zone. Here, accompanied by his sandal bearer and wielding a mace, the human person of the ruler—wearing the White Crown and other regalia—is about to strike his enemy, labeled "Harpoon." The figure of Narmer is presented at larger scale than any other figure in the image, larger, in fact, than any figure in the entire known chain of replications of the image of the ruler's victory. The rebus in the reverse top zone appears almost squeezed in. In the next flip from reverse top to obverse bottom (from Episode Three to Episode Two), the picture of the ruler smiting is replaced by what seems to be its metaphorical equivalent—namely, the picture, in the obverse middle, of the ruler's two retainers mastering two serpopards. (The retainers are distinguished by hairstyle and dress both from the ruler's other followers, such as the standard bearers in the obverse top zone, and from the ruler's enemies, such as the fleeing or crushed figures in the obverse and reverse bottom zones, but it is not clear what these differences are supposed to indicate. The men look somewhat like the curly-haired, bearded enemies of the lion-ruler on the Battlefield Palette [Fig. 33], although they clearly do not have the same status in the narrative.) If the ruler is Falcon and Bull, the serpopards are possibly "Fortress" and "Desert Kite," or, in another popular (but overliteral and anachronistic) interpretation, the two territories of the Nile valley, Lower Egypt (Red Crown) and Upper Egypt (White Crown), united by Narmer (see Gilbert 1949). Finally, in the flip from obverse bottom

to reverse bottom (from Episode Two to Episode One), the picture of Narmer smiting his enemy, removed from view after the first flip, reappears. Thus, no matter how the viewer flips the palette to determine the relation between the zones of depiction spread across it, Narmer smiting his enemy continually appears in the text.

Assuming the general condition of intelligibility of such images to be that the viewer must begin with the top of the obverse, the most logical sequence—Episode Four (obverse top) to Episode One (reverse bottom)—is an inversion of the "natural," forward chronological and causal direction of the fabula. For this reason the viewer is encouraged to retrieve other sequences as well. In investigating these alternatives, the one completely non inverted sequence, which would present the fabula in the order of its forward logic as Episodes One-Two-Three-Four, would be the most difficult for a contemporary viewer to attain. It would require the strongest violation of the established conditions of the intelligibility of images, for it would mean beginning with the reverse bottom of the palette (Episode One) rather than the obverse top (Episode Four) and scanning bottom to top rather than top to bottom.

Other possible sequences and segmentations—other possible "stories" working with the underlying narrative material—would arrange differently the chronological and causal armature of the fabula as presented in the "natural" sequence of Episodes One-Two-Three-Four. All of these fall somewhere in between the two possibilities respectively closest to and furthest from the established conditions of intelligibility for viewing images in the chain of replications (the order Episodes Four-Three-Two-One and Episodes One-Two-Three-Four, respectively). And all of them seem to be more or less equally available options for a viewer handling and scanning the six separate zones of depiction on the two sides of the Narmer Palette. For example, because on the Narmer Palette the fabula is consistently storied after-to-before in two dimensions of the viewing of the text, top to bottom and obverse to reverse (Fig. 39), it can be coherently interpreted—depending on which dimension a viewer selects to pursue first—as breaking into parallel sets of episodes in turn possibly to be regarded as simultaneous, successive, or metaphorical in relation to each other. Thus the obverse can be viewed from top to bottom as a first two-

episode segment of story (Episodes Two-Four: ruler as Bull captures enemy town and decapitation of enemies). This segment would be succeeded, after flipping the palette, by a second two-episode segment of story from top to bottom (Episodes One-Three: enemies fleeing and Falcon's presentation of the enemies of the ruler). The transition between the two episodes in each set and between the two sets is appropriately depicted as the ruler's blow, in the pictures of the retainers mastering serpopards (obverse middle) and the ruler smiting his enemy (reverse middle). This particular sequence takes the form of Episodes Four-(blow)-Two-(blow)-Three-(blow)-One.

As an alternative arrangement, these two sets—obverse top to bottom and reverse top to bottom—need not be regarded as causally or chronologically successive episodes, or "chapters," of the story. The obverse and reverse may simply be parallel recitations of the same story: Episodes Four-Two (obverse top/obverse bottom) = Episodes Three-One (reverse top/reverse bottom). Here the same story has a different, distinctive visual text in the case of each set of two zones, which thus stand in a metaphorical relation. For example, in the obverse story (Four-Two) the ruler appears as Red Crown, Flail, and Bull, while in the reverse story (Three-One) the ruler appears as White Crown, Mace, and Falcon. Again the two parallel stories each depict the ruler's blow.

At first glance this general finding—that several possible story sequences can be constructed by a viewer chasing the narrative image—seems to be consistent with what we have already seen of the open texture of preceding late prehistoric narrative images in the chain of replications. In one sense the presence of the ruler's decisive blow is masked by the ambiguity of the text; in another sense the ambiguity of the text is progressively resolved as centered in the ruler's blow.

Compared with earlier replications, however, the Narmer Palette exhibits many more possibilities for constructing the narrative image. For one thing the composition of the image presents more clearly separate zones of depiction than had been produced earlier, multiplying the possible choices for segmentation, grouping, or sequencing. Moreover, in its placement, scale, and register framing, the image repeatedly brings the viewer back to the picture of the ruler wielding his blow. Whereas in earlier images the text elided or masked the

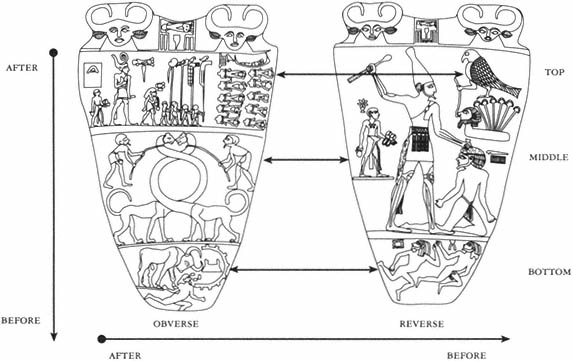

Fig. 41.

Detail of Narmer Palette, obverse: ruler's retainers mastering

two serpopards.

From Wildung 1981.

picture of the ruler wielding his blow, the Narmer Palette, on first glance, is more explicit: the human person of Narmer is about to smite his enemy. It is as if the very elaboration of the viewing activity requires a stronger, more direct and mimetic presentation of exactly what is being or is to be viewed—a closure of the openness in the image. Because the viewer chases the view, the view must now chase the viewer. The Narmer Palette both exemplifies and figures this encirclement, this tightening of the narrative noose—and to that extent masks it. But before we investigate this matter, there are other elementary structural features of the narrative organization of the image to be considered.

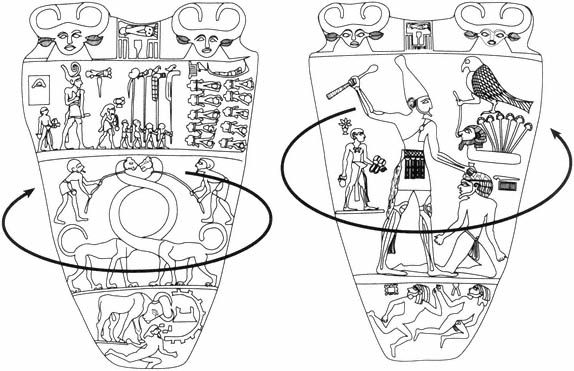

With Two Hands

The text provides the viewer with a key to the cipher of the narrative image at exactly the place where the palette would be both grasped and flipped—namely, the depiction of the ruler's two retainers mastering the two serpopards (Fig. 41). They represent the ruler's as well as the viewer's own blow in viewing the image: the two serpopards are the two sides of the palette to be twisted around one another in the viewer's hands. Whatever their role as metaphors for the ruler's victory, the figures of the retainers, textually associated with the

viewer's own hands, are depicted as moving in a clockwise circle (from obverse flipping right hand over left hand toward reverse), gradually twisting together the long necks of the beasts from their heads down to their bodies. The palette must be viewed by starting with the obverse top scene and always flipping the palette right hand over left in the same direction and always scanning top to bottom.

If the viewer adopts and, without interruption, continues to follow this means of chasing the view (Fig. 42), then a simple continuous twist will be generated. It can be summarized as follows:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The viewer's own interruptions of this twist, and the order of the story episodes that it unfolds, might include retrieving the sequence as close to the logic of the fabula as the text provides if the general conditions of intelligibility are still to be observed (that is, Episodes Four-Three-Two-One in the story for One-Two-Three-Four in the fabula). Alternatively, violating the general conditions, the viewer might retrieve sequences that follow the logic of the fabula even more closely still (for example, One-Two-Three-Four in the story for One-Two-Three-Four in the fabula).

In contrast to these possible, and partial, sequencings, the full twist (Fig. 42) both obeys all the general conditions of intelligibility of prehistoric image making and, given those conditions, takes the viewer through all the

Fig. 42.

Sequence of flips in reading the Narmer Palette, obverse and reverse.

available sequences of all zones of the depiction. On completing this twist at the obverse bottom, the viewer—presuming a continuing observance of the general conditions of intelligibility—would repeat the same full twist over again, beginning another series of flips. This simple, continuous twist allows the viewer to construct what I call the "canonical" form of the narrative image available in the Narmer Palette. Obeying all the general conditions of intelligibility of this mode of image making, it incorporates all possible forms of sequencing available within that context. Returning to the obverse, whence the construction of the narrative began, the viewer progresses through this canonical pictorial text making ten complete flips of the two-sided palette. An appropriate metaphor for this activity, or a key indication for adopting it, might be the two rows of five decapitated enemies, ten in all, depicted in the obverse top zone where the text "begins."

Emphasis and Ekphrasis

We have examined so far the arrangement of the fabula in the story presented by the image—especially the basic, "canonical" presentation (Fig. 42)—simply in terms of the connectedness of the four episodes. But the properties of the pictorial text invest the canonical sequence (and, in different ways, other possible sequences) with cumulative properties—what might be called a narrative "tone." The most important element of the pictorial text is the continual reappearance, the underlining, of the ruler standing firm on his ground line and stabilizing the "center" of the image on a horizontal axis—the pictures of the ruler's blow—as the palette continually rotates around its vertical axis. Moreover, although the top and bottom zones on the two sides are all episodes in the story, they are not all textually alike.

For example, consider the textual qualities of and relation between the first two logically closest episodes in the palette's inverted storying of the fabula (that is, the properties and relations of Episode Four, obverse top, and Episode Three, reverse top [Fig. 39]). In the canonical form of the image (Fig. 42) and in the inverted storying of the fabula the viewer retrieves in accepting the canonical form, Episode Four precedes Episode Three. In fact, in the canonical

from and any other sequencing that still obeys the general rule of beginning with the obverse of the palette, Episode Four, the obverse top zone, "begins" the text, while Episode Three, the reverse top, turns up later and necessarily after a flip of the palette. Already, then, the text of Episode Four, the depiction on the obverse top zone, must prepare the viewer for the text of Episode Three, the rebus on the reverse top. In the pictorial text of Episode Four the ten decapitated enemies, depicted frontally, and the ruler's retinue, depicted in profile, literally ground the viewer's point of view: the viewer is placed above and looking down on the enemies while being on the same level as and at the side of the ruler's group. The picture is a graphic depiction of the human person of the ruler with crown, costume, and regalia, his chief retainers, and his army as well as the specific fate of the enemies, with many attributes of costume and individual gesture carefully rendered. Some of this ekphrastic detail has a narrative status. For example, the decapitated heads of the enemies must be connected with the depiction in the rebus—"later" in the viewing of the narrative, if "earlier" in the fabula—of Falcon lifting an enemy's head for him to be executed. Some of this description, however, according to the logic of pictorial textuality, is superfluous for the purposes of the narrative (see the Appendix). Compare the textualization of similar narrative material in the rebus, pictorially the least explicit of all the zones of the image, where ekphrasis is at a minimum. To represent the ruler's many enemies the maker used a single enemy head, without details of body, and plants possibly symbolizing the enemy territory of Papyrus Land. In fact, as a rebus, this passage of the text on the Narmer Palette modulates pictorial textuality into another species of textualitY altogether, quite close to if not identical with ideographic script.

Other zones in the depiction stand between these two relatively extreme possibilities of greater or lesser descriptive richness in the pictorial notation. Three quasi-hieroglyphic zones of pictorial textuality (obverse middle, obverse bottom, and reverse top) can be distiguished from three descriptive zones (obverse top, reverse middle, and reverse bottom). In the descriptive zones pictorial text is supplemented with symbolic labels (the signs for Nar-Mer, Harpoon, Fortress, Desert Kite, and so forth)—that is, with nonpictorial text—but such symbols are not to be expected in the "hieroglyphic" zones (cipher key, Bull

and citadel, and rebus), which are nearly or completely modulated into nonpictorial text anyway.

These and other textual differences among passages of depiction necessarily play out in the way the narrative image is interpreted by the viewer. For example, in the canonical construction of the image the viewer encounters Episode Two (Bull attacks citadel), in the obverse bottom, after the descriptive Episode Four (ruler inspects corpses), the obverse top, and before the hieroglyphic Episode Three (Falcon presents enemy), the reverse top (Figs. 41, 42). In this midway position Episode Two seems pictorially more descriptive than a group of hieroglyphs or a rebus: its figures of Bull and enemy are visually separated one from the other, and the hieroglyph labeling the hometown of the enemies on the reverse bottom is treated here as an actual picture of their citadel. But the same Episode Two on the obverse bottom is less a pictorial description than is the picture on the obverse top, where the ruler inspects his enemies. Therefore, in the first segment of the canonical sequence (obverse top-obverse middle-obverse bottom-reverse top = Episode Four-[cipher key/picture of blow]-Episode Two-Episode Three), the narratiVe image begins with a graphic, vivid look at the "end" of the fabula with the defeated, decapitated enemies (obverse top); next, gives the viewer the key required for unfolding the story leading up to it, the retainers strangling the serpopards (obverse middle); next, goes back in sketchy detail to a much earlier episode, the taking of the town (obverse bottom); next, telegraphs the connection between the taking of the town and execution of prisoners, presented in the two episodes already viewed, should the viewer fail to infer it, and simultaneously anchors further material it introduces (the rebus in the reverse top); and so forth. As in experiencing modern novels and films, the viewer-reader progresses through paragraphs of dense description for and brief summaries of events nested in an armature of foreshadowings and recapitulations—the montage editing of long or short takes in close-up, deep-focus, and zoom perspective, with greater or less clarity, color, and so on.

It is not feasible to continue the description begun in the previous paragraph of the Narmer Palette's narrative image, enumerating all the textual properties of every possible segmentation and sequencing. We should, however,

at least notice how the four episodes of story at the top and bottom of the two sides of the palette are related to the two central passages of text, those with the narrative function of seeming to picture the ruler's blow that the fabula requires as taking place throughout the story—from pursuing the enemies to taking their town, to rounding up the prisoners, to executing them. One passage, with retainers and serpopards, is more hieroglyphic and the other, with the ruler smiting his enemy, has a more descriptive text. Both zones have singular emphasis—they appear at larger scale and in the center of the composition on either side—precisely because of their relatively greater narrative significance: that is, the fact that the incident related in them occurs repeatedly. Consistent with the overall organization of the image—obverse-to-reverse/ top-to-bottom—as after-to-before (Fig. 39), the obverse middle depicts the moment immediately after the decisive blow has fallen: here the serpopards have just been caught and their heads begun to be twisted together. The reverse middle depicts the moment immediately before the blow: here Narmer throws back his right arm, carrying his mace, just about to smite his enemy. The blow as it strikes its target, after the preliminaries to the blow and before the aftermath of the blow, must be in the center of the image—namely, in the wild place, the cosmetic saucer, where the owner of the palette or even the viewer reaches down to mix eye paint.

Escaping the Noose

Whereas in preceding late prehistoric images (Figs. 26, 28, 33) the absence of the ruler's decisive blow appeared as an ellipsis in the text while the viewer chased the narrative image, the pursuit of the ellipsis on the Narmer Palette is advanced into the text itself. As they twist together the necks of the serpopards (Fig. 41), the ruler's retainers are also depicted as tightening a noose around the wild space in the center of the image, the cosmetic saucer, where the ruler's blow at the instant it strikes its target must fall. In continually flipping the palette to retrieve the image caught and recaught in its twist (Fig. 42), the viewer thus seems to come closer and closer to seeing the falling of the blow, to pulling the noose tight around it with his or her own hands.

Fig. 43.

Canonical form of the narrative image on the Narmer Palette.

But in fact, although the picture of Narmer raising his mace appears again and again in the canonical form of the image, the blow escapes depiction and the image continues to mask it. While there is no need to describe all of its textual properties and relations (we have looked briefly at the first segment), the full viewing sequence through ten flips gives the narrative image on the Narmer Palette a complete, canonical text of eighteen zones—that is, the three sets of possible ways of scanning the six zones on the two sides according to the general conditions of intelligibility of late prehistoric image making, these sets sequenced in turn to accord with the same conditions. This complete text can be mapped as follows (Fig. 43):

1. OBV top (Episode Four)

2. OBV middle (cipher/after the blow)

3. OBV bottom (Episode Two)—flip

4. REV top (Episode Three)

5. REV middle (before the blow)

6. REV bottom (Episode One) [completes top-to-bottom set]

7. REV top (Episode Three)—flip

8. OBV top (Episode Four)

9. OBV middle (cipher/after the blow)—flip

10. REV middle (before the blow)

11. REV bottom (Episode One)—flip

12. OBV bottom (Episode Two) [completes side-to-side set]—flip

13. REV top (Episode Three)—flip

14. OBV middle (cipher/after the blow)—flip

15. REV bottom (Episode One)—flip

16. OBV top (Episode Four)—flip

17. REV middle (before the blow)—flip

18. OBV bottom (Episode Two) [completes double-twist set]

Several features stand out in this text. First, the rate of flipping speeds up as the text progresses—it literally becomes three times faster at the end than at the beginning. By the end of the text casual viewers may long since have abandoned it; but viewers accepting the general conditions of intelligibility and following the instructions of the cipher key will experience its accumulating excitement as a physical sensation—like a roller-coaster ride that begins slowly and then rockets through the final stretch.

Second, in the first set of flips (top to bottom, zones 1–6), the enemies' execution (Episode Four) and the enemies' flight (Episode One) begin and end the segment or "chapter" (as zones 1, 6). In the fabula these episodes are separated by the greatest temporal span. In the next and second set of flips (side to side, zones 7–12), the enemies' capture (Episode Three) and the taking of the town (Episode Two) begin and end the segment (as zones 7, 12). In the fabula these episodes are separated by a lesser temporal span. In the center of this segment, and of the text as a whole (zones 9, 10), the viewer seems as close temporally to the blow as it is possible to get insofar as the blow is not directly depicted (9, 10 = "after the blow" followed by "before the blow," the least temporal span of all). But in the third and final set of flips (double twist, zones 13–18), that temporal closeness is forced open again. The enemies' capture

(Episode Three) and the taking of the town (Episode Two), as they had earlier (zones 13, 18 = zones 7, 12), enclose the aftermath of the blow and what precedes the blow (zones 14, 17 = zones 9, 10); but they, in turn, enclose the greatest temporal span in the fabula (zones 15, 1 6)—namely, the enemies' flight (Episode One) and the enemies' execution (Episode Four). In sum, despite the increasing pace of the viewing, or precisely because of it, the image relates the greatest possible temporal span of the fabula as entirely caught up within the king's blow, the central, focal moment. The viewer is not led closer and closer to the blow, for the blow is outside and around whatever the viewer's viewing unfolds. In the way it relates details and passages of depiction, the storying works to establish a principal metaphor of the image—an expression of the continuousness of the ruler's blow.

Third, it is not just that the viewer fails to see the ruler's blow; it comes at the viewer from precisely where the viewer is not looking. While in the ten obverse-to-reverse flips of the palette the ruler's retainers twist the serpopards together clockwise (Figs. 41, 42), the ruler with his mace raised to strike (Fig. 44)—poised precisely on the other side of the place where the viewer begins—is always about to strike counterclockwise in the reverse-to-obverse direction. Therefore—like the lion on the Hunter's Palette (Fig. 28)—the viewer fails to see the ruler coming up around and "behind" him. The noose will twist off the head of the viewer before it is tight enough to capture the ruler's blow; in the viewer's cumulative and dizzying viewing of the image, the ruler pulls the noose tight as his blow, and the viewer becomes its victim. At the beginning of the text, then, like the ruler viewing his executed enemies, the viewer is invited by the image to enter the scene (obverse top, zone 1): the viewer marches beside the ruler and looks down on the decapitated corpses. But at the end of the text (by zone 18), the viewer understands the real import of the scene initially viewed—it was, after all, the "last" scene (Episode Four): the viewer leaves the text as yet another victim of the ruler's blow.

Considering what we have noted so far, it is not surprising that although in viewing the image the viewer may seem to unmask the ruler's appearances and come ever closer to seeing the blow taking place throughout, ten flips of the palette serve finally to remask the ruler. The ruler is always escaping the

Fig. 44.

Direction of retainers' twist and viewer's flips and direction of ruler's blow on the Narmer Palette, obverse and reverse.

depiction of the identity the viewer believes to be wielding the actual blow. According to the scheme whereby the six zones of the two sides of the palette (eighteen in all in the canonical form of the image [Fig. 43]) are presented in two visibly different modes of pictorial textuality—a descriptive or ekphrastic mode (D ) and a hieroglyphic (H ) mode—the sequence of these modes can be mapped as follows:

D H H H D D (top-to-bottom set, zones 1–6);

H D H D D H (side-to-side set, zones 7–12);

H H D D D H (double-twist set, zones 13–18).

In the first set of flips (top to bottom), after a graphic description of the final episode, Episode Four, the enemies' execution (zone 1), the preceding episodes are presented in less descriptive, hieroglyphic pictorial text (zones 2–4), then reviewed in more descriptive terms (zones 5, 6). For the viewer setting out to view the image, it would seem that the "masked" depictions of the ruler—as Bull and Falcon—are to be unmasked and his human person smiting his enemy revealed.

The lure of unmasking the ruler, and of finding the real climax of the narrative, sets the viewer off on a further series of flips, resulting in entrapment in the ruler's noose (zones 7–18). A parallel device can be found in other late prehistoric images—for example, on the Oxford Palette a victim moves toward the lure of the hunter's presence only to be attacked from behind (Fig. 27)—but the Narmer Palette handles this arrangement as a metaphor in its turn: the viewer is now a "victim." After a dizzying exchange of maskings and unmasings (zones 7–12), in which the viewer can never be certain where the ruler really is in the narrative (indeed he appears to be throughout it), the viewing ends with the thRee moSt descriptive depictions of the ruler (zones 15–17) enclosed by the three most hieroglyphic (zones 13, 14, 18). Since the arrangement of episodes in the story embeds the gReatest temporal span within the least temporal span, the pictorial text for this story can be said to embed descriptive specificity within hieroglyphic generality. It turns what would ordinarily be a simple inversion of spatiotemporal and causal logic, for the purposes of arranging a story, into a metaphor for the narrative as a whole—an expression of the universality of the blow paralleling its continuousness. Visible every time

the viewer flips to the reverse side of the palette (flips 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9), the picture of Narmer smiting his enemy is textually present in a full half of the narrative.

For these reasons the picture of Narmer smiting his enemy becomes not only an episode of or story element in the narrative in which it is embedded but also a symbol of that narrative. In fact it advances into a single passage of text (reverse middle zone) the pictorial dynamics of the entire narrative image as it is spread over a series of passages segmented and sequenced in various ways. In other words the reverse middle zone with the ruler smiting his enemy presents the metaphor that is not directly depicted in any one of the zones but rather is constructed by the complete concatenation of all the zones: it is the pictorial symbol of the metaphorical content of the narrative.

Extracting a Symbol from the Narrative

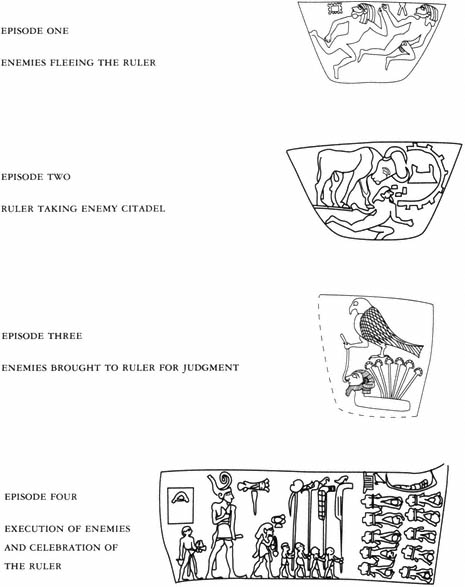

In what has been called the main "symbolic image" of the Narmer Palette (Schäfer 1957), the rebus in the reverse top right zone (Fig. 45) is not divided from the picture of the ruler smiting his enemy by a register line like those separating the pictorial zones elsewhere on the palette. It would seem, therefore, that whereas the late prehistoric narrative image calls for considering the reverse top and the reverse middle zones as distinct passages of pictorial narrative text, the pictorial symbol of the narrative also contained on the palette dictates that they should not be so distinguished.

In the symbolic image, in which reverse top and reverse middle zones are not separated, the depiction explicitly shows that Falcon lifts the enemy's face to gaze directly at the face of the ruler Narmer. Unlike the fleeing enemy on the Battlefield Palette (Fig. 33, obverse, third zone), who looks behind him to see and acknowledge the victorious lion-ruler facing away from him, here Narmer's enemy, subdued by Falcon, faces the master who takes possession of him. Just below, however, is a less compliant enemy (labeled as "harpoon" or coming from harpoon territory"), grasped by Narmer himself; although his body faces away from Narmer, the ruler twists his head completely around. The ruler must be grasping the enemy's topknot, for his clenched fist reaches into

Fig. 45.

Symbolic image on the Narmer Palette, reverse.

From Wildung 1981.

the enemy's hair. A small rectangular form protrudes slightly over or "behind" Narmer's fist, but as it is not placed immediately "behind" Narmer's thumb resting over his curled fingers it cannot actually represent the enemy's hair. It appears to be an object Narmer is wearing on the back of his hand or wrist, perhaps the cylindrical roll seal belonging to the case (?, possibly a square box with a lid) suspended by a strap around the neck of his sandal bearer, standing behind him to the left. (The sign or image on Narmer's seal is apparently depicted in the upper left corner in the obverse top zone of the palette, at the very beginning of the pictorial text. The scene of smiting an enemy is replicated, in later images like the Libyan or Booty Palette [Fig. 53] and many canonical representations of figures adopting the "smiting" pose [for example, Smith 1949: 169–71, 245–48; see Davis 1989: 80–82], as a metaphor for taking possession of, surveying, or enumerating properties—an act literally accomplished in ancient Egyptian and ancient Near Eastern societies by impressing a seal.)

Narmer stands fixed to a solid ground line drawn below the group from side to side of the palette. Since the mace points up, rather than down, and considering the way Narmer's arm, wrist, and hand are rendered, the blow will swing in the moment of smiting forcefully to the side of the enemy's head, caving it in or knocking it off; presumably the ten decapitated enemies in the obverse top zone are the aftermath of such a blow. Narmer's decisive blow, then, must arc through a wild, unrepresented space—an ellipsis in the image's specification of "place"—from the point of view of figures ranged along the depicted ground line. As with the preceding late prehistoric images, the ruler's deadly force enters the world from outside, where it cannot be seen. In this case his force comes directly from the place—like the cosmetic saucer on the obverse—where the real viewers of the palette must be standing, invited to view the narrative image as followers of the ruler, and where the ruler himself must be standing behind them, for his blow will, in the full unfolding of the narrative, take the viewers too. In the depiction the doomed enemy seems about to slump on the ground line. When the blow falls his broken body will collapse forward along the ground line or at right angles to it, in any case "falling off " the ground line and "out of" the picture into an unrepresented place. But, again,

in the full unfolding of the narrative image, all the places "in back of," "beside," and "in front of" the palette have been mastered by the ruler in the counterclockwise direction of his blow.

In addition to the rebus and the figure of Narmer smiting the enemy, the symbolic image on the reverse contains a third element. Behind the ruler and placed on his own small ground line, Narmer's personal servant waits on the sidelines to perform his services. The viewer has already met him in the introduction to the narrative image (obverse top zone), where he follows "behind" Narmer. In both passages he carries the ruler's sandals (apparently bound to his wrist), a water jug or oil container, a small wooden case for holding the ruler's seal(?) strapped around his neck, and slung around his waist a bowl with two long hanging flaps of cloth, possibly for washing.[3] Above his head two "hiero-glyphs"—a "royal" rosette, a flower from a lileacious plant, and an object that could contain sandals (Vandier 1952: 597) or might be the bulb of the plant—apparently give his title (see also Schott 1950: 22).

While the sandal bearer in the obverse top zone has a relatively straightforward place in the highly detailed description of the enemies' execution, matters are by no means as clear on the reverse of the palette. The sandal bearer appears to be part of the reverse middle passage of depiction; he seems to accompany the ruler just before the moment of his decisive blow. And yet, since he has his own ground line placed in the left portion of the composition, he could also belong to the reverse top zone, facing and complementing the rebus. According to this view the passage of pictorial text above the principal ground line on the reverse (middle and top zones) presents a "close-up" but also more "hieroglyphic" view of the scene depicted on the obverse top—that is, the ruler, accompanied by his personal servant and other companions (represented by Falcon), executing his enemies.

Why, then, should the sandal bearer be the only one of the ruler's retainers, of the several depicted in the introduction to the narrative image, to stand near the ruler just before the decisive blow? Although on the obverse top he has an obvious, if limited, place in the narrative image by filling out the ekphrasis at the beginning of the sTory, why should he be included in the text that symbolizes the narrative as a whole? Why, in the symbolic image, does he occupy the

place walking beside or behind the ruler—the place the viewer occupies in the beginning of the narrative and by its end discovers as being struck by the ruler's blow? Finally, if we treat the entire reverse side of the palette as part of the symbolic image, can it be significant that the fleeing enemies below the ground line look over their shoulders not only at the ruler but also at the sandal bearer (no other such glances across register lines appearing on the Narmer Palette, though common between zones in earlier replications)? Are we looking simply at the compositional and iconographic ambiguity necessarily inherent in a passage of text that functions simultaneously as part of a narrative image and as a symbol of the narrative whole?—or are we looking at the maker's, or the viewer's, difficulty in extracting a symbolic whole out of a narrative image?

If the symbolic image on the reverse of the palette extracts from the entire narrative the same metaphor for the sandal bearer as for the group of ruler and enemy, then the sandal bearer's position as "coming up behind" spatially might be interpreted as his continuous, universal temporal place. Like the ruler smiting his enemy, he too must be before, after, and throughout the story of the blow—with the difference that throughout he is masked from the sight of the enemy, for Narmer stands between the sandal bearer and the falling enemy.

The pictorial text places the sandal bearer directly below the ruler's raised arm clenching its mace. After the blow falls, then, he could move "forward" to assume the ruler's place. Thus he can be regarded as the ruler's heir-apparent.[4] With the heir-apparent on the left ("future" or "after") side of the blow, the two enemies depicted below Narmer's ground line (reverse bottom zone) are correlatively placed to the ruler's right (the "past" side of the blow), looking back in the very direction the blow will be coming toward them (Fig. 44). Like the ruler's heir-apparent, they could be said to have a place in the symbol in both the "before" and the "after" stages of the blow. Before the blow—in the forward direction of the narrative image—they flee the ruler's deadly wrath, are pursued, and are destroyed (Figs. 40, 43). After the blow—and in the message of the narrative image extracted by its symbol—they acknowledge Narmer's successor. Their apparent change of heart is indicated in the pictorial text by a gesture somewhat like the raised hand of the fleeing enemy on the Battlefield Palette earlier in the chain of replications (Fig. 33): while the left enemy raises

his left hand and looks back over his right shoulder, the right enemy reverses direction, raising his right hand and looking back over his left shoulder. In either case, the pictorial text depicts them as able to see fully only what is behind them—the power and danger of the ruler, whom they can observe by twisting their heads back even further to their left (resulting in death by decapitation) or completely around to their right (that is, changing their point of view).

Chasing the Viewer

Considering its place in the composition of the narrative text and its status as an independent symbolic text, the major image on the reverse side of the palette (Fig. 45) presents the continuity of the blow, plaited through and tightening a noose around history and therefore an order both outside and a precondition of that history as a continuous cycle of after-to-before and before-to-after. In all of history the ruler—and his dynasty—is always coming around in the other direction from his enemy.

In short, considering both the narrative image and the symbolic image metaphorically related to it, the pictorial text on the Narmer Palette—the viewer's experience of the representation of the ruler's blow—has become the homolog of the message of the fabula. Viewing the Narmer Palette is, itself, an example of the ruler's victory.

Henceforth this mechanism and ones like it will become the canonical narrativity of the art of the dynastic Egyptian state, which literally subordinates the viewer of its representations to and by those representations (Davis 1989: 192–224). But it is also true that in the Narmer Palette the open texture of late prehistoric representation becomes closed and another mode of representation is instituted in its place. The open activity of the viewer chasing an image masking the blow of the ruler now becomes an image masking the blow of the ruler chasing the viewer—and closing in (Figs. 40–45). Notwithstanding the two sides and several zones of depiction, and the possibility of different ways of scanning, segmenting, and sequencing them, the insistence of the image on the Narmer Palette cannot be ignored: in the text it regulates the story sequence

by the use of register lines and repeatedly introduces or inserts and magnifies the scale of the ruler; in metaphor it expresses the continuousness and universality of his blow; and in symbol it represents and reduces the narrative. It is not possible to escape when the ruler is always there, everywhere.

Some viewers of the Narmer Palette may not, in fact, have pursued the narrative image all the way through its complex canonical form (Fig. 43), despite it's having derived from and replicated late prehistoric narrativity. For them the symbolic image on the reverse side of the palette—the choice of a single striking icon to stand for the whole narrative image—was the dominant aspect of the pictorial text (Fig. 45). Singular in its compositional scale and framed by register ground lines, the symbolic image of Narmer about to strike his enemy pushes the other zones of depiction to the side. As the representation of the narrative in which it functions and which it replaces in the very operation of so doing, the pictorial symbol on the reverse side of the Narmer Palette becomes interpretable independent of the narrative image. It can be treated as an entirely discrete text, a second image on the Narmer Palette existing alongside and representing the narrative image. As has been written of the frescoes in the synagogue at Dura Europos, "The two modes, the 'abbreviated' and not always fittingly called the 'symbolic' on the one hand, and the 'narrative' on the other, were not always sharply separated from each other but sometimes used side by side within the same work of art, and they may penetrate each other and become fused" (Weitzmann and Kessler 1990: 149; see also Winter 1985: 20–21, 27–28).

In the constitution of the canonical tradition in the early dynastic period, later artists selected the symbolic image for replication as such (Figs. 48–50). They took it as an independently meaningful visual text that could be applied in new scenes of representation the image maker of the Narmer Palette could never have anticipated. Moreover, as far as we can tell, these image makers also suppressed the replication of the late prehistoric narrative image from which this symbol derived and in which it was initially embedded (see Davis 1989: 64–82, 159–71, 189–91; Hall 1989). The complex disjunctive metaphorics by which the ruler edges into and turns about in the ground of nature—the metaphorics of the Ostrich, Oxford, and Hunter's Palettes (Figs. 25, 26,

28)—no longer needed to be reproduced when the metaphor had fully gained its ground and become standard usage, a literal reality that could be designated in symbol; in the emerging canonical tradition representation now did an about-face to face the ruler.

The chain of replications, then, is radically revised at the time of the Narmer Palette. A break occurs in the continuity of the metaphorics of the chain; it shifts from the continuous replication of a metaphor of the ruler's victory to a replication of an independent symbol of the metaphor. Rather than symbol appearing as a reductive selection from the complexity of a narrative, as it must have seemed to the immediately contemporary viewers of the Narmer Palette familiar with late prehistoric image making, narrative now appears for succeeding viewers as an elaboration of an established symbol. On the Narmer Palette late prehistoric narrativity thus comes to an end. Precisely because the late prehistoric narrative precipitates a non-narrative symbol that claims to state the full generality of the narrative, any and all possible versions of the narrative become metaphorical instances of the symbol. The previous metaphorics recede from view and the new symbol seems to refer, as the earlier metaphorics had done, directly to experience in the world.

This is not to say that the newly established symbol of the ruler's victory would not be narratively constructed in itself in canonical representation, and in all kinds of disjunctively related ways—just as, for example, the Carnarvon knife handle (Fig. 23) and succeeding late prehistoric images (Figs. 25, 26, 28, 33) had narrativized the symbols on the animal-rows and carnivores-and-prey designs (Figs. 8–10, 20–22). As we would expect, canonical narrative metaphorics are subjected equally, in turn, to the extraction of particular symbols—for instance, a remarkably stable image of the happy and successful courtier (Fig. 2)—and the suppression of sometimes alternative, but frequently unacceptable, metaphorical associations within a general horizon of unrevisability. (For instance, while sexuality is not absent from Egyptian image making and perhaps had a remote metaphorical root in the phallic prowess of great animals and successful hunters or rulers connoted in certain late prehistoric images, the official image of the courtier did not usually include explicit representation of his sexual pleasures, as it did in Greek Archaic and Classical vase

painting or in certain Japanese elite arts.) Canonical image makers took up several "core motifs" with diverse historical origins. In fact they balanced dynastic symbols, like the ruler smiting (Hall 1989), with equally or even more archaic symbols perhaps more familiar to the ordinary experience of the Egyptian population, like scenes of gaming, fishing, or farming (useful selections in Klebs 1915, 1922, 1932; Vandier 1964). They could establish further metaphorical relations among these symbols, such as an image of the hunter, fisher, or farmer as the ruler smiting or vice versa (see Davis 1989: 80–81). But all this complex activity in the scene of representation is a matter for the intricate history of the canonical tradition after the revision of the chain of replications of late prehistoric image making being examined here.