Distinctions and Enumerations and Their Implications

We can make a first approach to the year's collection of annual events by summarizing and enumerating, where possible, some of their distinguishing features.

1. In the course of a year there are seventy-nine named annual events, occasionally grouped so that there are more than one in a day, and with

one event lasting two days. The seventy-nine events thus occupy to some greater or lesser extent seventy-four days.[1]

2. These seventy-nine annual events are of greatly differing importance. On the basis of the comparative amounts of city personnel, space, resources, and time devoted to them, as well as our opinion of their significance to Bhaktapur as a city, we have sorted the annual events into those of major, moderate, and minor importance. It is fairly easy to discern at the two extremes major events and the often very trivial minor ones, but the inclusion of an event in the middle category, "moderate importance," is often somewhat arbitrary. At any rate, our sorting gives us twenty-five major events (many of which we grouped into "focal" festival sequences), twenty-eight events of moderate importance, and twenty-six events of minor importance among the year's seventy-nine annual events. Thus we have some fifty-three events that we take to be of some more than minor annual importance to the city.

3. If we sort the annual events by the social-spatial unit, which is emphasized, we find that only two such events are primarily occasions for individual activities, that is, vratas ([42] and [43]). Twenty of the seventy-nine annual events are of primary concern to the household —although many other events entail household activities that are secondary to some activity in the public city. In contrast to household-centered events (and in contrast to a predominant emphasis in rites of passage), only two events may be said to be directed primarily to the phuki , but one of these is the fundamental phuki -defining Dewali [30].[2] The majority of annual events are those fifty festivals of various kinds located primarily in public city space . Four annual events have their loci out of the city , and there are an additional two such events attended by those whose loss of a parent makes them unable to worship a father or mother in the two annual household ceremonies devoted to their worship. Finally there are two events ([18] and [34]) whose spatial location is ambiguous for this classification, the latter case—not exactly an "event" in the same sense as other days—concerning both the household and the phuki .

The "primary" annual household events, in contrast to the household phases of rites of passage and to those household pujas motivated by some specific familial problem, are generally observed by all city households on the same day, and are in this sense "city-wide" events. Thus, almost all the annual events are either such parallel household

events or take place in the public city space, and may be amalgamated together into a class of civic events emphasizing the public city and households as units of that city. On closer inspection, as we shall see, these household events and events in public city space are differently related to civic life.

The primary household events insofar as they take place in parallel throughout the city are civic events, but in another distinction they take place below the level of the public city. In such a view, certain annual events—and segments of particular events—are occasionally above the city level, many more are below it, but most are at the level of the city, the fifty events located in public space being, by definition, at that level. Above the city level are the melas where individuals from Bhaktapur join with individuals from other cities and from other ethnic groups in pilgrimages to one or another Valley shrine, all, significantly, located out of the major Valley cities. In melas Bhaktapur's participants escape their city and its particular order. Individuals join in a larger human community, refracting themselves against another context than the city's public order, the city being reflected only in its absence. The characteristic annual events below the level of the public city are the calendrically determined household events, centered, for the most part, on the moral life of the household and its benign deities.

One important difference between household and public events requires a repeated comment. Competent members of a household must (as an index of that competence) participate in its ceremonies, as phuki members must participate in rites of passage and other phuki ceremonies. But participation in public ceremonies is, for the most part, voluntary for the mass of observers (although not for the central actors). Thus public ceremonies must have their own special ways of motivating attendance.[3] We have discussed some of the sources of the attraction of the important performances in previous chapters. These include their aesthetic qualities, their mystery, their intriguing complexity, their sacred and supernatural auras and, in some cases, the thrill of their dangers. The vivid presence of a deity in human form, its living manifestation in the Kumari maiden or the Nine Durgas, is an almost irresistible attraction. Many of the stories, dramas, and symbolic forms of the festivals engage and fascinate because they have compelling psychodynamic interest and resonate with the personal psychological forms out of which the public citizen is constructed. The tales of the phallic snakes issuing from the princess's nose and the banging together of the chariots of Bhairava and Bhadrakali[*] in Biska:, the blood sac-

rifices of Mohani, and the echoes of human sacrifice in the Nine Durgas' pyakha(n) are vivid examples.[4]

4. The deities who are foci of the various annual events include all of the major members of the city pantheon, a few quasi-deities or supernatural figures who exist only for the purpose of a particular festival, and some social categories—e.g., father, mother—treated as deities. For the benign deities there are eight events devoted to Visnu/Narayana[*] (including here Dattatreya), four devoted to Krsna[*] , and one each to Jagana and Rama. There are four devoted to Siva—one as Pasupatinatha, two as Mahadeva, and one (his only primary appearance in a household event) as Mahesvara in conjunction with his consort Uma. Ganesa[*] is the focus of four festivals, Laksmi and Sarasvati of two each. Yama or his representatives have three; nagas , one; the Rsis[*] , one; the deified river, one; and the cow deity, Vaitarani, one. Family members are worshiped as quasi-deities in four events. The family priest is worshiped on one occasion as purohita , on another as guru .

The dangerous goddess Devi in one form or another is the focus of about twenty-two occasions of which ten are in the Devi cycle. (Three of the events in the Devi cycle do not refer directly to Devi but are essential components of that cycle.) Bhairava—in himself and not as the consort of Devi—is the focus of two festivals and in tandem with his consort, Bhadrakali[*] , at the center of the Biska: sequence, which lasts ten days. The dangerous deity Bhisi(n), who is conceptually isolated from the Devi-Bhairava group, is the central deity of one event.

All the city's major deities are thus the subject of one or more festivals during the year; they are all duly honored. But the extent and nature of the festival use of the various deities and types of deities are quite different. The dangerous deities are never the focus of primary household annual events,[5] but they are the center of more than half of the events in the public city, and of all the urban structural focal sequences. The remaining minority of the public festivals, those of the benign deities, are divided among those deities, with Visnu[*] having the largest number, eight—or sixteen if his avatars are amalgamated to him. Siva, the putatively predominant deity of the Shaivite Hindu Newars, is, typically, hardly represented at all for the purposes of the on-the-ground concrete work of the festivals. His major festival Sila Ca:re (Sivaratri [15]) taking place, for the most part, at a pilgrimage site elsewhere in the valley.

While the festivals in the public city of the benign deities, whose

exemplary figure is Visnu[*] , are often said to be "in honor of" those morally representative figures, the public festivals of the dangerous deities not only honor and display those figures, but in contrast to the festivals of the benign deities, do something more. These are the public urban festivals, which are sometimes said to be not just for the gods but "for the people." These festivals make use of the special metamoral force of the dangerous deities as guarantors of order.

Not every event has a focal deity—some half dozen events are simply annual occasions for doing something or have some reference to a demonic or legendary figure (e.g., [45] and [65]) with references to major deities only in the far background.

5. Some annual calendrical events are of particular concern to certain categories of people in Bhaktapur—students, women, farmers, upper-level thars , merchants, Brahmans, people who have been bereaved during the previous year. The vast majority of the events concern all of Bhakatapur's people, however, with the traditional exception of the most polluting thars . A different question, however, is the representation of the city's various hierarchical macrosocial roles in the cast of characters of the festival enactments. In most cases the human actors on the public stage are simply the pujari attendants of the focal deities and the musicians (usually from one of the Jyapu thars ) who may accompany the deity in its procession. Thus the vast majority of public festivals do not represent the divisions of the city's elaborate differentiated macrostatus system. It is only in the year's two major festival sequences, Biska: and Mohani, that there is some complex and differentiated representation of Bhaktapur's macrosocial status system. Yet, even here the representation is sketchy. The king and his chief Brahman are given some centrality, and the court, other priests, farmers, and polluting thars are represented, but for the most part these actors are simply used as a clumped and static resume[*] of the city's ranks. The focal festivals do not, with one or two trivial exceptions, show any dramatic relations among actors characterized by their social statuses. Whatever the dilemmas, paradoxes, conflicts, and problems that are explored in the annual festivals, the components of Bhaktapur's social system are privileged and taken for granted. The levels and the other components of the macrostatus system are not used to provide agonists in the drama, not used to illustrate conflict and its possible resolutions. In the midst of all the drama of annual events the hierarchical system of social statuses is protected, represented only as a unified actor, an actor who

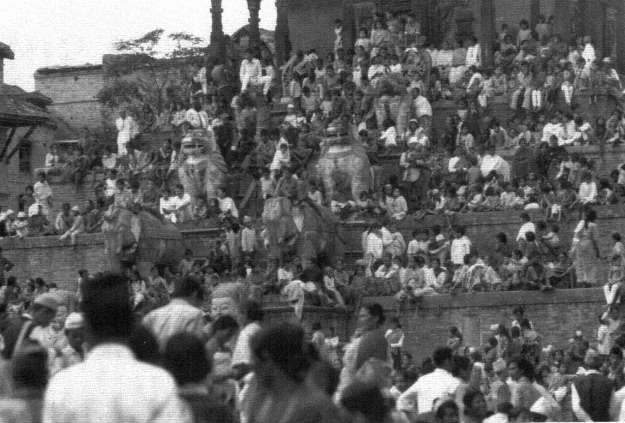

Figure 34.

Spectators seated on the steps of the Natapwa(n)la temple in Ta:marhi Square to watch the struggle to pull the

Bhairava chariot.

is, sometimes, as is the case pervasively throughout city symbolism, put in contrast with an "external" and oppositional social actor, the untouchable. The potential drama of the interplay and conflicts of macro-statuses is deflected and played out elsewhere—not in the symbolic enactments of the annual events, whose surfaces and middle depths, at least, speak of other dramas.[6]

It has been said of some of the festivals of the Hellenic pagan cities of the second and third centuries A.D. that they "showed off the city in its social hierarchy: people processed in a specified order of social rank, the magistrates, priests and councillors and even the city's athletic victors, if any" (Fox 1986, 80). Those festivals seem to have not only represented the city's statuses but also celebrated the particular citizens who temporarily captured roles in the hierarchy. The particular individuals who occupy the roles in Bhaktapur's largely ascribed—not achieved—status system do not need to be supported by such public advertisement. If Bhaktapur's social system is represented only in its unity, the individuals who happen to hold these statuses are completely dissolved in the immemorial roles they play in the annual festivals.

In summary, most (some 63%) of Bhaktapur's annual events are in the city's public space, with the calendrically coordinated household festivals following in quantity (25%). Almost, but not quite, all of the annual events have direct reference to deities, the annual calendar being largely a "religious calendar." The dangerous deities only appear when the primary or only locus of the event is in public space, but they are then dominant. And, in contrast to the minutely detailed dramatic interactions of various city spaces, of spatially located social units, of deities and times, the macrosocial system is portrayed only as a unified presence in the dramas of the yearly calendar.