Reorganizing the Gold Rush: Mining Companies in the Gold Fields

In the absence of established cities and towns, mining districts became the basic political unit in California's gold fields. Although they initially had no legal standing,

Handbill of the California Emigration Society, Boston, advertising passage to

California "in a first-rate Clipper Ship." Published in 1856, it promoted the

economic opportunities to be found in the new El Dorado. On the verso, notice

was made of mining companies offering wages of "$4.00 per day and board to

steady workmen," testifying to the transformation of gold mining from individual

adventure to corporate enterprise. Courtesy Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif .

codes were framed by the miners of each locale, which regulated both social behavior and mineral rights within the district. So fundamental did these miners' codes become to the regulation of mining that both state and federal governments refused to intervene for nearly two decades. While miners' codes varied across California's mining districts, two elements were central to nearly all of them: discovery and work. The man who "discovered" or "claimed" an area, then marked it and recorded the location, acquired its mineral rights. To retain these rights, the codes required miners to work their claims steadily, as many as twenty days per month in some districts. Most of the early codes limited claim size to what a single person could mine alone, initially 100 to 150 square feet. Size limits and work requirements effectively prevented absentee ownership and the monopoly of mining claims, both of which were strongly opposed by most miners.[17] It is no surprise, then, that in his study of western mining camps, historian Charles Shinn judged that buying, selling, and speculating in mining claims were activities that were probably foreign concepts to the early gold-rush miners.[18] Individual rights were paramount. As miner Samuel Upham observed, "no chartered institutions have monopolized the great avenues to wealth. . . . everyone has an equal chance to rise. . . . Neither business nor capital can oppress labor in California."[19] Equality of ownership was the principle underlying the mining codes.

Within this context, working miners, a majority of the early population in the mining districts, viewed one another in a particular light. "All men who had or expected to have any standing in the community were required to work with their hands, labor was dignified and honorable," wrote early California historian Theodore Hittell, "the man who did not live by actual physical toil was regarded as a sort of social excrescence or parasite."[20]

Yet things changed quickly in the gold fields. By April 1850, John Banks, a former member of the Buckeye Rovers, an Ohio company, described what typically happened in each new mining camp. Newcomers arrived steadily, forming "almost one continuous stream of men. Every place is snatched up in a moment. This canyon is claimed to its very head, nearly 20 miles, each man being allowed but 20 feet."[21] As the number of gold seekers outpaced the number of claims discovered, and as the technology and capital needed to work the diggings exceeded the resources of individual miners, they formed partnerships and joint-stock associations and worked together. California historian and philosopher Josiah Royce referred to this organizing tendency as a unique attribute of the American character, "a natural political instinct," yet it was based on practical experience.[22] As gold-rush traveler and miner J. D. Borthwick observed, despite the "spirit of individual independence" many Americans proclaimed, "they are certainly of all people in the world the most prompt to organize and combine to carry out a common object. They are trained to it from their youth in their innumerable, and to a foreigner, unintelligible caucus-meetings, committees, conventions, and so forth."[23] To men already accustomed to working to-

gether for mutual advantage, forming companies to pursue mining operations seemed an obvious alternative. Indeed, the miners had little choice, as earnings fell steadily through the early 1850s. Estimated at about $20 per day in 1848, miners' daily wages dropped from about $16 in 1849 to $10 in 1850 and to $8 or less in 1851, and down to about $3 a day between 1856 and 1860.[24] At the same time, another change took place. Between 1848 and about 1850, miners' "wages" referred to earnings from a day of mining, whether the individual worked on his own account or was employed by a company.[25] By 1851 fewer men mined "on their own hook," and the term took on its modern connotation: the earnings of wage laborers.

Mining underwent a transformation. From individual adventure and competition, mining operations began to resemble factories in the eastern states and Europe, with distinct divisions of labor and differential pay scales. While competition over claims increased and miners' wages fell, easily acquired gold was fast depleted. On July 15, 1851, San Francisco's leading newspaper, the Alta California , appeared pessimistic about prospects for the industry: "Now we hear of the complete exhaustion and abandonment of many of the diggings." Miner John Banks felt the stress acutely: "We have left our claim like hundreds of others. . . . Misery loves company; we have plenty. . . . Men are frightened, some starving, confused, not knowing what to do, where to go. . . . Prospecting is a necessity and a dangerous business."[26]

Technological advances, such as the rocker, the sluice box, and the long tom, permitted miners to work more efficiently. By instituting a division of labor, miners were able to exploit their claims more systematically than was possible working alone. While the work was rigorous, costs were relatively low given the labor-intensive methods of placer mining. Gold-field mining companies, mostly partnerships and joint-stock companies, shared many similarities to the pioneer mining companies in which so many had emigrated. Both were voluntary associations in which members participated equally or proportionally in the labor, costs, and profits, if any. Members exercised voting rights on company decisions, worked under an elected foreman, and operated on the principle of joint shares.[27] Claims turned over quickly, as miners made a discovery, swarmed in to exploit it, and moved on. Mining partnerships and companies formed quickly and could be dissolved just as quickly when things went wrong, as they often did. Rampant rumors sent miners scrambling from one reputed bonanza to the next. A few lucky souls struck pay dirt, but most struggled, subsisting on whatever came to hand.

Though many gold-rush adventurers returned home with empty pockets, others applied themselves to solving the technical and organizational problems of mining for gold. To solve the major obstacles to finding, extracting, and processing gold, miners developed three new large-scale approaches to mining during the early 1850s: river, quartz, and hydraulic mining. Each approach had its own particular set of costs. In river mining operations, supplies and building materials for flumes, dams, and ditches

Miner Prospecting , a hand-colored lithograph designed and drawn by Charles Nahl and

August Wenderoth, illustrates the archetypal California gold seeker of romance and legend.

The two artists, who spent the summer of 1851 mining at Rough and Ready in Nevada

County, portrayed the heavily armed and well-outfitted Argonaut as solitary, self-reliant, and

resourceful. Published in San Francisco in 1852, the print contributed to the popular image of

the gold hunter that has endured for a century and a half. Courtesy Bancroft Library .

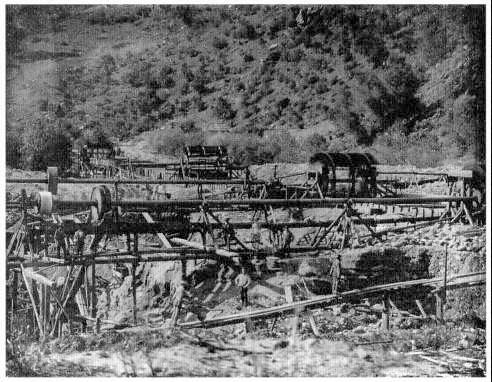

River mining, about 1852. A dam has been constructed upstream, diverting the watercourse

into a flume, visible on a diagonal cutting across the daguerreotype image. The large water

wheels powered by the flume turn huge driveshafts, connected by leather belts to pumps,

which keep the exposed riverbed dry. Though highly speculative, river mining was widely

practiced, the first of the large-scale entrepreneurial enterprises pursued in the diggings. In

1853 several companies working independently spent three million dollars turning twenty-five

miles of the Yuba out of its bed. Courtesy Bancroft Library .

consumed money. Similarly, hydraulic operations required huge quantities of water delivered to the mine site, while quartz mining involved extracting gold through deep shafts, then crushing and processing the ore, all expensive undertakings, particularly when the technology available then allowed for the recovery of so small a percentage of the gold. While technology presented formidable challenges to the miners, lawsuits over disputed claims and water rights became increasingly common. For years to come, law and water developed as subsidiary industries to mining.

Fighting lawsuits, building flumes and ditches, and developing large-scale quartz mining operations all required capital. Despite rising gold production during 1850 and 1851, the large number of men and the growing difficulty of extracting the gold led to changes in social relations in the gold fields and transformed the organization of mining operations. Until 1851, most money invested in California mines was pro-

duced by the miners themselves. With the changes and experiments with new technology and high interest rates on borrowing, the need for outside investment was apparent if the industry was to grow. At the same time, some observers viewed the organization of joint-stock companies and corporations as a positive sign that more stable industrial organization was emerging to displace the turbulent era of gold-rush adventurers. Felix P. Wierzbicki, who described his tour of the gold fields in a widely quoted pamphlet, California as It Is & as It May Be, Or a Guide to the Gold Region , predicted that "When this gold mania ceases to rage, individuals will abandon the mines; and then there will be a good opportunity for companies with heavy capital to step in; there will be enough profitable work for them; and it is then that the country will enter on a career of real progress, and not until then."[28]