Yellow Earth :

Western Analysis and a Non-Western Text

Esther C. M. Yau

Vol. 41, no. 2 (Winter 1987–88): 22–33.

1984. China. The wounds of the Cultural Revolution have been healing for nearly a decade. After the hysterical tides of red flags, the fanatical chanting of political slogans, and militant Mao supporters in khaki green or white shirts and blue slacks paving every inch of Tienanmen Square, come the flashy Toshiba billboards for refrigerators and washing machines, the catchy phrases of "Four Modernizations," and tranquilized consumers in colorful outfits and leather heels crowding the shops of Wangfujing Street. A context of Change. Yet contradiction prevails. Who are these people flocking to local theaters that posted First Blood on their billboards? Are they not the same group that gathered for lessons on anti-spiritual pollution? The Red Book and the pocket calculator are drawn from shirt pockets without haste, just like the old long pipe from the baggy pants of the peasant waiting for the old Master of Heavens to take care of the order of things. In 1984, after the crash of the Gang of Four, when China becomes a phenomenon of the "post"—a nation fragmented by and suffering from the collapse of faith in the modern socialist politics and culture—the search for meaning by the perturbed Chinese character begins to occupy the electric shadows of new Chinese cinema.[1]

At the end of 1984, a few Chinese men who were obsessed with their history and culture—all of them had labored in factories and farms during the Cultural Revolution and just graduated from the Beijing Film Academy—quietly completed Huang Tudi in a very small production unit, the Guangxi Studio, in Southern China. A serious feature that had basically eluded political censorship, Huang Tudi (which meant Yellow Earth ) was soon regarded as the most significant stylistic breakthrough in new Chinese cinema. It won several festival prizes, started major debates at home about filmmaking, and interested international film scholars.[2]

Safely set in the 1930s, Yellow Earth tells the story of an encounter between a soldier and some peasants. Despite its ambitious attempt to capture both the richly nourishing and the quietly destructive elements of an ancient civilization

already torn apart in the late nineteenth century, the film's story and its use of folksongs/folktale as device and structure is deceptively simple and unpretentious. In fact, the film's conception and its musical mode were originally derived from one of the trite literary screenplays which glorified the peasants and the earlier years of socialist revolution: an Eighth Route Army soldier influenced a peasant girl to struggle away from her feudal family.[3] Such a commonplace narrative of misunderstanding-enlightenment-liberation-trial-triumph or its variations would be just another boring cliché to the audience familiar with socialist myths, while the singing and romance could be a welcome diversion. Dissatisfied with the original story but captivated by the folk-tale elements, director Chen Kaige and his young classmates—all in their early thirties—scouted the Shaanxi Province in northwestern China for months on foot. Their anthropological observations of the local people and their subcultures both enriched and shaped the narrative, cultural, and aesthetic elements in the film.[4] Consequently, they brought onto the international screen a very different version of Chinese people—hardworking, hungry, and benevolent peasants who look inactive but whose storage of vitality would be released in their struggles for survival and in their celebration of living. The structure of the original story was kept, but Yellow Earth has woven a very troubling picture of Chinese feudal culture in human terms that had never been conjured up so vividly before by urban intellectuals.

The film's narrative: 1937. The socialist revolution has started in western China, but most other areas are still controlled by the Guomindang. Some Eighth Route Army soldiers are sent to the still "unliberated" western highlands of Shaanbei to collect folk tunes for army songs. Film begins. Spring, 1939. An Eighth Route Army soldier, Gu Qing, reaches a village in which a feudal marriage between a young bride and a middle-aged peasant is taking place. Later, the soldier is hosted in the cave home of a middle-aged widower peasant living with his young daughter and son. Gu Qing works in the fields with them and tells them of the social changes brought about by the revolution, which include the army women's chances to become literate and to have freedom of marriage. The peasant's daughter, Cuiqiao, is interested in Gu Qing's stories about life outside the village, and she sings a number of "sour tunes" about herself. The peasant's son, Hanhan, sings a bed-wetting song for Gu Qing, and is taught a revolutionary song in return.[5] The young girl learns that her father has accepted the village matchmaker's arrangement for her betrothal. Soon, the soldier announces his departure. Before he leaves, the peasant sings him a "sour tune," and Cuiqiao privately begs him to take her away to join the army. Gu Qing refuses on grounds of public officers' rules but promises to apply for her and to return to the village once permission is granted. Soon after his departure, Cuiqiao's feudal marriage with a middle-

aged peasant takes place. At the army base, Gu Qing watches some peasants drum-dancing to soldiers going off to join the anti-Japanese war. Back in the village, Cuiqiao decides to run away to join the army herself. She disappears crossing the Yellow River while singing the revolutionary song. Another spring comes. There is a drought on the land. As the soldier returns to the village, he sees that a prayer for rain involving all the male peasants is taking place. Fanatic with their prayers, nobody notices Gu Qing's return, except the peasant's young son. In the final shots he rushes to meet the soldier, struggling against the rush of worshippers. End of story.

Yellow Earth poses a number of issues that intrigued both censors and the local audience. The film seems to be ironic: the soldier's failure to bring about any change (whether material or ideological) in the face of invincible feudalism and superstition among the masses transgresses socialist literary standards and rejects the official signifieds. However, such an irony is destabilized or even reversed within the film, in the sequences depicting the vivacious drum-dancing by the liberated peasants and the positive reactions of the young generation (i.e., Cuiqiao and Hanhan) towards revolution. The censors were highly dissatisfied with the film's "indulgence with poverty and backwardness, projecting a negative image of the country." Still, there were no politically offensive sequences to lead to full-scale denunciation and banning.[6] To the audience used to tear-jerking melodramas (in the Chinese case, those of Xie Jin, who is by far the most successful and popular director[7] ), Yellow Earth has missed most of the opportune moments for dialogue and tension, and is thus unnecessarily opaque and flat. For example, according to typical Chinese melodrama, the scenes where Cuiqiao is forced to marry an older stranger, and the one when her tiny boat disappears from the turbulent Yellow River, would both be exploited as moments for pathos. But here they are treated metonymically: in the first, the rough dark hand extending from off-screen to unveil the red headcloth of the bride is all one sees of her feudalist "victimizer"; in the second instance, the empty shots of the river simply obscure the question of her death. In both situations, some emotional impact is conveyed vocally, in the first by the frightened breathing of the bride, and in the second by the interruption of her singing. But the cinematic construction is incomplete, creating an uncertainty in meaning and a distancing effect in an audience trained on melodrama and classical editing. Nevertheless, when the film was premiered at the 1985 Hong Kong International Film Festival, it was lauded immediately as "an outstanding breakthrough," "expressing deep sentiments poured onto one's national roots" and "a bold exploration of film language." Such an enthusiastic reception modified the derogatory official reaction towards the film (similar to some initial Western reception, but for different political reasons), and in turn prompted the local urbanites to give it some box-office support.[8]

Aesthetically speaking, Yellow Earth is a significant instance of a non-Western alternative in recent narrative film-making. The static views of distant ravines and slopes of the Loess Plateau resemble a Chinese scroll-painting of the Chang'an School. Consistent with Chinese art, Zhang Yimou's cinematography works with a limited range of colors, natural lighting, and a non-perspectival use of filmic space that aspires to a Taoist thought: "Silent is the Roaring Sound, Formless is the Image Grand."[9] Centrifugal spatial configurations open up to a consciousness that is not moved by desire but rather by the lack of it—the "telling" moments are often represented in extreme long shots with little depth when sky and horizon are proportioned to an extreme, leaving a lot of "empty spaces" within the frame. The tyranny of (socialist) signifiers and their signifieds is contested in this approach in which classical Chinese painting's representation of nature is deployed to create an appearance of a "zero" political coding. Indeed, the film's political discourse has little to do with official socialism; rather, it begins with a radical departure from the (imported) mainstream style and (opportunist) priorities of narrative film-making in China. One may even suggest that Yellow Earth is an "avant-gardist" attempt by young Chinese film-makers taking cover under the abstractionist ambiguities of classical Chinese painting.[10]

To film-makers and scholars, then, Yellow Earth raises some intriguing questions: What is the relationship between the aesthetic practice and the political discourse of this film? In what way is the text different from and incommensurable with the master narratives (socialist dogma, mainstream film-making, classical editing style, etc.), in what way is it "already written" (by patriarchy, especially) as an ideological production of that culture and society, and finally, how does this non-Western text elude the logocentric character of Western textual analysis as well as the sweeping historicism of cultural criticism?[11]

This essay will address the above questions by opening up the text of Yellow Earth (as many modernist texts have been pried open) with sets of contemporary Western methods of close reading—cine-structuralist, Barthesian post-structuralist, neo-Marxian culturalist, and feminist discursive. This will place Yellow Earth among the many parsimoniously plural texts and satisfy the relentless decipherers of signifieds and their curiosity for an oriental text. The following discussion of this text will show that the movement of the narrative and text of Yellow Earth involves the interweaving and work of four structurally balanced strands (micro-narratives) on three levels: a diegetic level (for the construction of and inquiry about cultural and historical meaning), a critical level (for the disowning and fragmentation of the socialist discourses), and a discursive level (for the polyvocal articulations of and about Chinese aesthetics and feudalist patriarchy).[12] In this way, I hope to identify certain premises of Chinese cosmological thinking and philosophy as related in and

through this text. In this analytic process, the contextual reading of Chinese culture and political history will show, however, the limitations of textual analysis and hence its critique.[13]

I shall begin with a brief description of the organization of the four narrative strands and their function on both diegetic and critical levels. The Lévi-Straussian structural analysis of myths is initially useful: the peasant father imposes feudal rules on Cuiqiao, the daughter (he marries her off to stabilize the kinship system), and the soldier imposes public officers' rules on her as well (he prevents her from joining the army before securing official approval). Thus, even though the host-guest relationship of the peasant and the soldier mobilizes other pairs of antinomies such as agriculture/warfare, subsistence/revolution, backwardness/modernization, the pattern of binaries breaks down when it comes to religion/politics, since both signify, in Chinese thinking, patriarchal power as a guardian figure. In addition, Hanhan, the young male heir in the film, counteracts the establishment (runs in the reverse direction of the praying patriarchs) in the same way Cuiqiao does (rows the boat against the Yellow River currents for her own liberation). Again, the antinomy peasant/soldier is destabilized, as myth is often disassembled in history—that is, the mythic glory of hierarchic dynasties and the revolutionary success of urban militia breaks down when confronted by the historical sensibility of the post–Cultural Revolution period.

There are four terms of description: brother, sister, father, soldier. While there is a relationship of consanguinity and descent, both are complicated by the problematic relation of affinity: Cuiqiao's intimacy with Hanhan and their distance from the peasant father is more excessive while romance is taboo and marriage is ritual in the film. The prohibition of incest among family members (Cuiqiao with her brother or father) is transferred to prohibition of romantic involvement between Cuiqiao and the soldier, enforced at the cost of the girl's life.[14] Hence, the textual alignment of patriarchy with sexual repression. However, the film text is not to be confused with an anthropological account. As both Fredric Jameson and Brian Henderson point out, historicism is at work in the complex mode of sign production and in reading.[15] Hence this text would preferably be read with a historical knowledge of the Communist Party's courtship with the peasants and its reconstruction of man [sic ] through the construction of socialist manhood—which reserves desire for the perfection of the ideological and economic revolution, while the liberation of women (its success a much-debated topic) becomes an apparatus for the Party's repression of male sexuality, besides being a means for winning a good reputation. Hence the position of contemporary Chinese women, generally speaking, involves a negotiation between patriarchy and socialist feminism in ways more complicated than what one deduces from the Lévi-Straussian analysis of kinship systems.

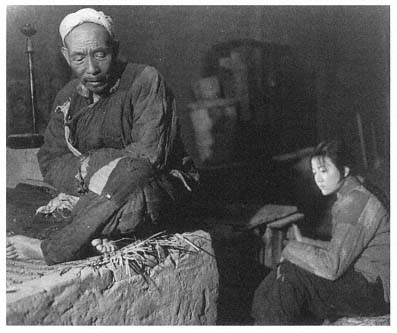

Yellow Earth: Father and daughter

Now I shall proceed to a more detailed (though non-exhaustive) discussion of what is at work in each of the micro-narratives as narrative strands, as well as the contextual readings relevant to the textual strategies.

First Narrative Strand:

The Peasant's Story

The scenes assembled for the first narrative strand have a strong ethnographic nature: the material relation between the Shaanbei peasants and their land is documented through the repetitive activities of ploughing land on bare slopes, getting water every day from the Yellow River ten miles away, tending sheep, cooking, and quiet residence inside the cave home, while marriages and rain prayers are treated with a moderate amount of exotic interest—of the urban Han people looking at their rural counterparts. The peasants are depicted as people of spare words (Cuiqiao's father even sings little: "What to sing about when [one is] neither happy nor sad?"). They have a practical philosophy (their aphorism: "friends of wine and meat, spouse of rice and flour") and they show a paternal benevolence (Cuiqiao's father only sings for the soldier for fear that the latter may lose a job if not enough folk tunes are collected). Obviously, anthropological details have been pretty well attended to.

Meaning is assigned according to a historical or even ontological dependence of peasants on their motherly Land and River. This signifying structure is first of all spatially articulated: the Loess landscape with its fascinating ancient face is a silent but major figure both in Chinese painting and in this film. Consistent with the "high and distant" perspective in scroll painting is the decentered framing with the spatial contemplation of miniaturized peasants as black dots laboring to cross the vast spans of warm yellow land to get to the river or their cave homes.[16] No collective farming appears in this film, and neither planting nor harvesting modify this relationship. The symbolic representation of an ancient agrarian sensibility is condensed in shots that include the bare details of one man, one cow, and one tree within the frame in which the horizon is always set at the upper level and the land, impressive with deep ravines, appears almost flattened. In an inconspicuous way, the Yellow River's meaning is also contemplated: the peasants are nourished by it and are sometimes destroyed by it. A narrative function is attached: this is a place in dire need of reform, and it is also stubbornly resistant. The state of this land and people accounts for the delay of enlightenment or modernity—there is an unquestioning reliance on metaphysical meaning, be it the Old Master of Heavens or the Dragon King of the Sea, but which is tied so closely to the survival of the village. The narrative refusal of and enthusiasm for revolution are motivated: the ideology of survival is a much stronger instinct than the passion for ideals. But to the peasants, the Party could have been one of the rain gods.

There is a vocal part to this cosmological expression as well, articulated dialectically for a critical purpose. We shall attend to three voices: the first, that of the peasant's respect for the land: "This old yellow earth, it lets you step on it with one foot and then another, turn it over with one plough after another. Can you take that like it does? Shouldn't you respect it?" A classical form of deification borne from a genuine, everyday relationship. Then it is countered by the second, the soldier's voice: "We collect folk songs—to spread out—to let the public know what we suffering people are sacrificing for, why we farmers [my emphasis] need a revolution." Gu Qing offers a rational reading of the agrarian beliefs; his statement contains a simple dialectic—the good earth brings only poverty, and the way out is revolution. Yet his statement and his belief are but a modernized form of deification: the revolution and its ultimate signified (the Revolutionary Leader) are offered to replace the mythic beliefs through a (false) identification by the soldier with the peasants ("Our Chairman likes folk songs," says the soldier). Blind loyalty (of peasants to land) finds homology in, and is renarrativized by, a rational discourse (of soldier to his Leader). The ancient structure of power changes hand here; thereafter, the feudalist circulation of women and socialist liberation of women will also remain homological.

As explicit contradiction between the first two voices remains unresolved, a major clash breaks out in the form of a third voice, which appears in the rain prayer sequence. Assembled in their desiccated land, the hungry peasants chant in one voice: "Dragon King of the Sea, Saves Tens of Thousands of People, Breezes and Drizzles, Saves Tens of Thousands of People." Desperation capsuled: the hungry bow fervently to the Heavens, then to their land, and then to their totemic Dragon King of the Sea, in a primitive form of survival instinct. At this moment the soldier appears (his return to the village) from a distance, silent. A 180° shot/reverse shot organizes their (non)encounter: a frontal view of the approaching soldier, followed by a rear view of the peasants whose collective blindness repudiates what the soldier signifies (remember his song "The Communist Party Saves Tens of Thousands of People"). In this summary moment of the people's agony and the film's most searing questioning of the Revolution's potential, the multiple signifieds are produced in and through a mirroring structure: the soldier's failure reflected by the peasants' behavior and the peasants' failure in the soldier's presence.

At the outset, two dialectical relationships are set up explicitly in the text, one against the other: between peasant and nonpeasant, and between peasant and land. The roots of feudalism, through this first narrative strand, are traced to their economic and cultural bases, and are compared in a striking way to Chinese socialism. In this manner, the whole micro-narrative is historicized to suggest reflections on contemporary China's economic and political fiascos. But there is another relationship between the filmic space and the audience's (focal) gaze. The nonperspectival presentation of landscapes in some shots and sequences often leads one's gaze to linear movements within the frame, following the contours of the yellow earth and the occasional appearance and disappearance of human figures in depth on an empty and seemingly flat surface. The land stretches within the frame, both horizontally and vertically, with an overpowering sense of scale and yet without being menacing. In these shots and sequences, the desire of one's gaze is not answered by the classical Western style of suturing; indeed it may even be frustrated.[17] Rather, this desire is dispersed in the decentered movement of the gaze (and shifts in eye level as well) at a centrifugal representation of symbolically limitless space. Such an unfocused spatial consciousness (maintained also by non-classical editing style) has a dialectical relationship with one's pleasure-seeking consciousness. It frustrates if one looks for phallocentric (or feminist, for that matter) obsessions within an appropriatable space, and it satisfies if one lets the sense of endlessness/emptiness take care of one's desire (i.e., a passage without narrative hold). In these instances, one sees an image without becoming its captive; in other words, one is not just the product of cinematic discourse (of shot/reverse shot, in particular), but still circulates within that discourse almost as "non-subject" (i.e., not chained tightly to signification).

Within the text of Yellow Earth , one may say, two kinds of pleasures are set up: a hermeneutic movement prompts the organization of cinematic discourse to hold interest, while the Taoist aesthetic contemplation releases that narrative hold from time to time. Most of the moments are assigned meaning and absences of narrative image are filled, though some have evaded meaning in the rationalist sense. When the latter occurs, the rigorous theoretical discourses one uses for deciphering are sometimes gently eluded.

Second Narrative Strand:

The Daughter's Story

Inasmuch as the sense of social identity defines the person within Chinese society, individuals in Chinese films are often cast as nonautonomous entities within determining familial, social, and national frameworks. Ever since the 1920s, the portrayals of individuals in films have been inextricably linked to institutions and do not reach resolution outside the latter. Hence, unlike the classical Hollywood style, homogeneity is not restored through the reconciliation of female desires with the male ones, and the ways of looking are not structured according to manipulations of visual pleasure (coding the erotic, specifically) in the language of the Western patriarchal order. With an integration of socialism with Confucian values, film texts after 1949 have often coded the political into both narrative development and visual structures, hence appropriating scopophilia for an asexual idealization. In the post–Cultural Revolution context, then, the critique of such a repressive practice naturally falls on the desexualizing (hence dehumanizing) discourses in the earlier years and their impact on the cultural and human psyche.[18]

The plotting of Yellow Earth , following the doomed fate of Cuiqiao the daughter, seems to have integrated the above view of social identity with the recent critique of dehumanizing political discourses. Within the second narrative strand, the exchange of women in paternally arranged marriages is chosen as the signifier of feudalist victimization of women, while the usual clichés of cruel fathers or class villains are replaced by kind paternal figures. The iconic use of feudal marriage ceremonies has become common literary and filmic practice since the 1930s, but compared with other texts, this one is more subtle and complex in its enunciation of sympathy for women.[19] In this regard, we may undertake to identify two sets of homological structures in the text that function for the above purpose. It is through the narrative and cinematic construction of these structures that Yellow Earth made its statement on patriarchal power as manifested in cultural, social, and political practices.

The first set of homological structures involves the spatial construction of two marriage processions, each characterized by a montage in close-up of the

advancing components (trumpet players, donkey, dowry, the red palanquin and its carriers) in more or less frontal views. In each case, the repetitive and excessive appearance of red, which culturally denotes happiness, fortune, and spontaneity, is reversed in its connotative meaning within the dramatic context of the oppressive marriages. More significantly, the absence/presence of Cuiqiao as an intradiegetic spectator and her look become a linchpin to that system of signification. In the first marriage sequence, the bride is led from the palanquin to kneel with the groom before the ancestor's plate and then taken to their bedroom. Meanwhile, Cuiqiao as a spectator is referred to three or four times in separate shots, establishing her looking as a significant reading of the movement of the narrative. Yet she is not detached from that narrative at all. Seeing her framed as standing at the doorway where Confucius's code of behavior for women is written, one is constantly reminded that Cuiqiao's inscription will be similarly completed (through marriage) within the Confucian code.[20] Her look identifies her with the scene of marriage, and also relays to the audience her narrative image as a young rural female. The victimizing structure (feudalist patriarchy) and the potential victim (Cuiqiao) are joined through a shot/reverse-shot method, mobilized by her looking which coded the social and the cultural into the signifying system here.

In the second marriage sequence, the similar analysis in close-up of the advancing procession (by a similar editing style) performs an act of recall, which as a transformed version of the first marriage sequence reminds the audience of Cuiqiao's role as the intradiegetic spectator previously. In this instance, however, Cuiqiao is the bride, locked behind the dull black door of the palanquin covered by a dazzlingly red cloth. The big close-up of the palanquin, however, suggests her presence within the shot (hidden), in depth, and going through the process of "fulfilling" the inscription predicted earlier on for her against her wish for freedom. The palanquin replaces her look but points to her absence/presence. At the same time, Hanhan, her quiet brother, replaces Cuiqiao as an intradiegetic spectator looking (almost at us) from the back of the palanquin, figuring her absence and her silence. Hanhan as the brother represents an ideal form of male sympathy in that context, yet as the son and heir of a feudal system, he is also potentially responsible for the perpetuation of this victimization. In this manner, the text shifts from a possible statement on class (backwardness of peasants before the Liberation) to a statement of culture (the closed system of patriarchy) to locate the woman's tragedy. With an intertextual understanding of most post-1949 Chinese films presenting feudal marriages, this cultural statement becomes a subtle comment on the (pro-revolutionary) textual appropriations of folk rituals for political rhetorics.

The second set of homological structures appears in two pairs of narrative relationships between three characters (between Cuiqiao's father and Cuiqiao, and

between Gu Qing the soldier and Cuiqiao) concerning the subject of women's (and Cuiqiao's) fate. Initially, one finds the first relationship a negative one while the second is positive, i.e., the father being feudal but the soldier liberating. This is encapsulated in a dialogue in which the soldier attempts to convince the peasants that women in socialist-administered regions receive education and choose their own husbands, and Cuiqiao's father answers: "How can that be? We farmers have rules." However, when one compares the peasants' exchange of women for the survival of the village and the revolutionaries' liberation of women for the promotion of the cause, then one finds both relationships being similarly fixated on woman as the Other in their production of meaning. Such a homology, nevertheless, is asymmetrical in presentation. On the one hand, the film is direct about the negative implications of the patrilinear family though without falling into a simple feminist logic (Cuiqiao's father sympathizes with women's tragedy in the sour tune he sings for the soldier). On the other, there is no questioning about the socialist recruitment of women (and Cuiqiao's failure to join the army is regarded as regrettable). The critique falls on another issue: Gu Qing's refusal to take Cuiqiao along with him because "We public officers have rules, we have to get the leader's approval." Thus it is nongendered bureaucracy that is at stake here, and not exactly the patriarchal aspects of the feudalist and socialist structures, which can only be identified from an extratextual position.

The suspected drowning of Cuiqiao, then, can be read as the textual negotiation with the symbolic loss of meaning: she is to be punished (by patriarchy, of course) for overturning the peasants' rule (by leaving her marriage), for brushing aside the public officers' rule (by leaving to join the army without permission), and for challenging nature's rule (by crossing the Yellow River when the currents are at their strongest).

When Cuiqiao is alive, the sour tunes she sings fill the film's sound track—musical signifiers narrating the sadness and the beauty of "yin." Her death, though tragic, brings into play the all-male spectacles in the text: drum-dancing and rain-prayer sequences each celebrating the strength and attraction of "yang," so much suppressed when women's issues were part of the mainstream political mores.[21] Here one detects the "split interest" of the text in these instances—the nonpolitical assignment of bearers of meaning (rather than the nonsexist) prescribes a masculine rather than feminine perspective of the narrative images of man and woman. That is to say, since the position of men and women in this patriarchal culture has been rearranged for the last three decades, first according to everyone's class background, then with a paternal favoring (as bias and strategy) of women, the text's critique of socialist discourses become its own articulation of a male perspective. In this way, this text does not escape being "overdetermined" by culture and society, although in some ways by default.

Third Narrative Strand:

The Eighth Route Army Soldier's Story

Since the Yan'an Forum for writers in 1942, literary writing in China followed a master narrative that privileged class consciousness over individual creativity.[22] In revolutionary realism, character types (and stereotypes) were considered the most effective methods of interpellating the masses during economic or political movements. Literary and filmic discourses on the social being dictate a structure of dichotomies: proletariat/bourgeois, Party members/non–Party members, allies/enemies, peasants/landlords, etc. It was not until 1978 that "wound literature" gave an ironic bent to the hagiographic mode for Party members and cadres. Still, such writing found shelter in specificity—for example, Xie Jin's The Legend of Tianyun Mountain and other adaptations from wound literature were bold in questioning the political persecution of intellectuals during the terrifying decade, unmistakably attributing the causes of people's suffering to the influences of the Gang of Four. Dichotomy, however, was basically maintained even though the introduction of good cadre/bad cadre did cause some reshuffling in the antinomies. Meanwhile, the master narrative remained intact, with authority diminished but the direct questioning of it taboo.[23]

The figure of an Eighth Route Army soldier and Party member in Yellow Earth , therefore, was not written without technical caution and political subtleties. A number of alterations to humanize the soldier were made during adaptation which to some extent decentralized his position in the narrative. Nevertheless, the rectitude of a revolutionary perspective and its influence on the peasants were not the least mitigated—that is to say, the third narrative strand sets the three others in motion. Thus, even when the representation of the Party member may be more in line with the popular notion, there is a level of operation that makes socialist interpretation plausible. One may say that with an audience used to being prompted by dialogue and behavior, the figure of Gu Qing does not contest the proper image of a revolutionary military man.

As a signifying structure, the soldier's story functions as (in)difference and as metonymy, which is where the ironic mode works. The figures of that ancient agrarian subculture are no longer the same when Gu Qing, the outsider, enters—they are transformed under the soldier's gaze of bewilderment, which subsequently exerts its critical import. It is the third strand that begins the braiding process among the four and is responsible for the climaxes: the daughter no longer submits to her father's wishes, the son abandons the rain-prayer ceremony. Yet, these changes take place virtually outside Gu Qing's knowledge: he is ignorant of Cuiqiao's dilemma (except about women's fate in

a general way) and of the peasants' problem of survival (except in broad terms of their poverty). The Party's political courtship with the peasants is metonymically dealt with here, in the prohibition of romance (as lack of knowledge) between Gu Qing and Cuiqiao, and also powerfully in the last scene of rain prayer which brought into circulation "hunger" as the peasants' signified (versus the power elite's lack of experience of it) for their rural human–land and marriage relationships. Tension between history and ideology was again condensed, the three to four decades' national history of socialism contesting to little avail the five thousand years' national ideology of subsistence. The peasants' hospitable reception of Gu Qing and Cuiqiao's idealistic trust in the Party further reinforce the ironic mode—difference is not a simple dichotomy and often works in the areas least expected. Then, none could go very far: Cuiqiao disappears in the Yellow River, the peasants are dying of drought, while the totemic figure of the Sea Dragon King dominates the scene, lifted by worshippers who want their lives saved. The discourse here is historicist: the cultural and epistemological barriers (of both Party and people) to the capitalist market economy in the 1980s motivates this myth of survival. Yet, it is also historical: the gods, emperors, leaders, all have been sought after by people in disaster, and made disasters by people.

The Fourth Strand:

Hanhan's Story

A quiet young boy with a blank facial expression, Hanhan moves almost inconspicuously as a curious figure in the scenes. One may even ponder a Brechtian address made possible by this marginal but conscious presence. Almost uninscribed by culture, and, to some extent, by the text itself, Hanhan has the greatest degree of differentiation (i.e., Hanhan = X) and exists to be taken up by the three other narrative strands for signification.[24]

As a peasant's son, Hanhan is heir to land, feudalism, and patriarchy. As a brother to Cuiqiao, he is the displaced site of her repressed feminine love and its failure. As a little pal of Gu Qing's he is the first person to learn the song and spirit of revolution. Yet his story is also underdeveloped. In other words, Hanhan is neither unconnected nor fixated in the textual generation of meaning. Contrary to the marked positions of other song singers (of either sour tunes or revolutionary songs), Hanhan is more ambiguous with his short "bed-wetting song" (which made unrefined jokes with both the Sea Dragon King and the son-in-law) before the soldier recruits his voice for the revolutionary song, which he sings only once. In the scene where he is already made part of the fanatic horde of worshippers, Hanhan turns towards

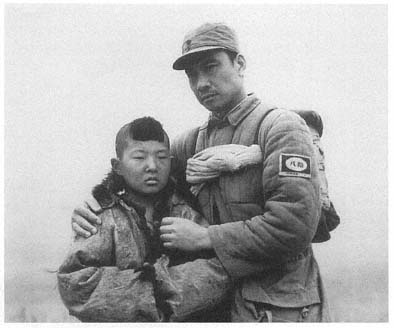

"The silent, blank face": Hanhan and the soldier in Yellow Earth

the sight of the soldier as the source of possible change in an act of individual decision.

However, it is not Hanhan the literary figure that escapes inscription. Indeed, pressured by political demands, the textual movement of Hanhan is along the trajectory of "liberation," though there is no intention of completing it. The circulation of Hanhan (as X) along the various narrative strands is, significantly, a production of textual interweaving. When conventional meaning in that society has been fragmented and questioned within the text, Hanhan (as a textual figure) functions as the desire for meaning. One may venture to say Hanhan is the signifier of that meaning—an insight for history and culture with an urge for change, portrayed as a childish moment before inscription, before meaning is fixed at the level of the political and agrarian institutions. Therefore the silent, blank face, because to speak, to have a facial expression, is to signify, to politicize.

A braid? Perhaps, as one woven by culture in society, and not flaunted as a fetish. Since the nineteenth century, major historical events in China (wars, national calamities, revolutions, etc.) have made four topics crucial to national consciousness: feudalism, subsistence, socialism, and modernization, and discourses are prompted in relation to them in numerous literary and cultural texts. In 1984, when contemporary China struggles with the evil spells of the

Cultural Revolution and begins flirting once again with the capitalist market economy, discourses related to the four topics reappear in terms of current issues: will the agrarian mentality of its people prevent China from becoming a modern nation? Will feudal relations persist in spite of the lure of individualist entrepreneurship? Will the country's recent radical economic move (as in the Great Leap Forward) bring another large-scale fiasco? Is the Communist Party leadership still competent for the changing 1980s? Will a second Cultural Revolution occur soon? As technology and business turn corporate and global, the answers to these questions can no longer be found in an isolated situation. The China that partakes in the world's market economy no longer operates in an "ideological context" that is uniquely Chinese (as it had during the Cultural Revolution). Inevitably (and maybe unfortunately), this changing, modernizing "ideological context" in China also informs the "avant-gardist" project of Yellow Earth which has focused its criticism only on the patriarchal and feudal ideologies of that culture. Arguably, then, Yellow Earth 's modernist power of critique of Chinese culture and history comes from its subtextual, noncritical proposition of capitalist-democracy as an alternative; it is (also arguably) this grain in the text that attracts the global-intellectual as well.

An historicist reading of texts and contexts is a powerful analytic practice. In the case of Yellow Earth , such a reading enables one to relate the film's textual strategies to the specific political and cultural context, while at the same time exposing some of the text's symptoms. However, there still remains a need to locate Yellow Earth 's difference from other interesting Chinese films made during the same period. Wu Tianming's Life (1984), for example, deals with the disparity between intellectual and agrarian life as an important subcultural dichotomy in Chinese identity and boldly pits individual motivation against class issues. Again, such a film is possible in China only in the 1980s. Yet, one may argue that discursive constraints are not fully watertight in their operations. With respect to Yellow Earth , there is a presence of a certain "negative dialectics" that seems to run counter to its grain of modernist activities and does not yield to an historicist reading. It is, again, the simple Taoist philosophy which (dis)empowers the text by (non)affirming speaking and looking: "Silent is the Roaring Sound, Formless is the Image Grand." There are many such instances in the film: when the human voice is absent and nobody looks, history and culture are present in these moments of power(lessness) of the text. With this philosophy, perhaps, we may be able to contemplate the power(lessness) of our reading of the text.