River History

River course and pattern changes were documented by comparing maps of the Carmel River from 1858 to 1945 and aerial photos of the river from 1939 to 1980.

Changes in Course

Historical changes in the Carmel River from Garland Ranch to the mouth are plotted in figures 4 and 5. The 1858 and 1882 channels were determined from boundary surveys. The 1911 course appears on the Monterey 15' USDI Geological Survey topographic map (quad) of 1913 (based on surveys in 1911–12), and the 1945 course is taken

Figure 3.

Location map, Middle and Lower Carmel River (base from Monterey, Seaside, and Carmel Valley 7.5' quads).

from the Monterey and Seaside 7.5' quads of 1947 (based on aerial photography in 1945). The 1947 maps were photorevised in 1968, but the only mapped revision in the river's course was downstream of Garland Ranch, where a northward bend of the river was eliminated by highway construction.

Comparison of these maps reveals nine localities where lateral channel migrations of 250–500 m. (820–1,640 ft.) occurred during the 87 years between 1858 and 1945. Except for the change near Garland Ranch Park, since the survey of 1911–1912, changes in course have been modest, generally less than 0.2 km. These migrations were gradual changes from 1911 to 1945, unlike the dramatic shifts that were wrought by floods in the preceding years. This is consistent with the observation that most major shifts take place during large floods. No floods comparable to the 1911 event occurred between that year and 1945, nor have they since.

Figures 4 and 5 show changes in the channel reach from San Clemente Dam downstream to Las Garzas Creek. The 1917 channel is plotted from the Jamesburg 15' quad of 1918 (from surveys in 1917). The 1954 course is from the Carmel Valley 7.5' quad of 1956 (compiled from 1954 aerial photography). The lack of dramatic changes comparable to those seen downvalley may be attributed to: 1) the lack of record prior to the 1860 and 1911 floods; and 2) bedrock confinement along much of this reach.

Flood History

The earliest flood on record along the Carmel River was the great statewide deluge of 1862. While no records exist to document the exact magnitude of this flood, it was severe enough to induce the few valley residents to move to higher ground.[3] Most of the great changes in channel course visible between the 1858 and 1882 channels in Rancho Canada de la Segunda probably occurred during this flood.

The next great flood occurred in 1911. An account in the "Monterey Cypress" of 11 March 1911 reported that Fannie Meadows and Roy Martin lost 10 acres and a pear orchard due to lateral migration of the river. Their adjacent properties extended downstream from the present Schulte Road to Meadows Road. The channel shift that consumed their land can be seen by comparing the river course of 1858 with that of 1911 (fig. 4).

[3] Roy Meadows. Personal communication of family history.

Figure 4.

Course changes of the Carmel River, Garland Ranch to mouth.

Figure 5.

Course changes of the Carmel River channel,

San Clemente Dam to Las Garzas Creek. Key:

dashed—1917 channel from 1918 edition

Jamesburg 15' quad; solid—1954 channel,

from 1956 edition Carmel Valley 7.5' quad.

The flood of 1911 was a big flood indeed. Before it was swept away, a staff gauge at the site of the San Clemente Dam indicated a discharge of 480 cms (17,000 cfs). The peak flow has been estimated at 708 cms (25,000 cfs). In 1914 another major flood occurred, but this one was far less destructive. It is not known whether this flood was significantly smaller than the 1911 event, or if it simply caused less disruption because it flowed through a channel pre-adjusted to the large 1911 flow.

No comparable floods occurred in the following decades. The absence of large floods, together with the drop in sediment load resulting from construction of the San Clemente Dam in 1921, served to permit channel narrowing, increased sinuosity, and bed degradation.

Changes in Sinuosity and Gradient

Sinuosity, defined as the ratio of stream channel length to valley length, was computed for several sequential channels. From 1911 to 1945, the reach of river from Garland Ranch to the mouth increased in sinuosity from 1.11 to 1.18. The reach from Sleepy Hollow to Las Garzas Creek experienced an overall increase in sinuosity of 1.05 to 1.09 from 1917 to 1954. Map slopes computed for the 1911 and 1945 channels from Garland Ranch to the mouth show a decrease from 0.0034 in 1911 to 0.0029 in 1945. The overall increase in sinuosity and decrease in gradient suggest that the Carmel River stabilized in the aftermath of the 1911 flood.

Changes in Channel Pattern and Form

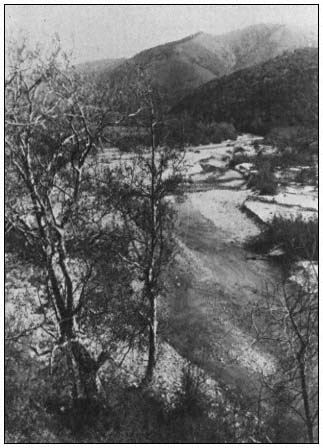

Channel pattern (pattern in plan view, e.g., meandering, braided) and form (cross sectional shape, e.g., narrow, wide) of the Lower and Middle Carmel River have changed dramatically since the last major flood and construction of the dams. No doubt, the entire Lower and Middle Carmel were strongly modified by the 1911 and 1914 floods. The resulting channel is probably well represented by the historical photos (ca. 1918) from the Slevin Collection (University of California, Berkeley). These photos of the

river, at and downstream of the Narrows (fig. 6 and 7), show a wide, sandy channel, reflecting the recent passage of a major flood.

By 1939, the Lower Carmel had developed a narrower, more sinuous channel while the Middle Carmel retained much of its braided character, as evidenced by aerial photography of 1939. Figure 7 shows the area pictured in figure 6 as it subsequently appeared in the 1930s. By this time, a riparian forest had developed along virtually all of the Lower Carmel River, narrowing the channel. Aerial photographs taken in 1965 show further development of vegetation and narrowing of the channel.

This change in channel pattern occurred concurrently with the increase in sinuosity and decrease in gradient apparent by 1945. Together, they indicate that the Lower Carmel had adjusted to the absence of major floods and the cut-off of 60% of its previous sediment load (based on drainage area upstream of San Clemente Dam). These adjustments included channel narrowing with encroaching vegetation, an increase in sinuosity, and reduction of gradient through incision.

Figure 6.

Carmel River channel, 1918, viewed from right bank

upstream from location of present Robinson Canyon

Road bridge, looking upstream. (Slevin Collection,

Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.)

Figure 7.

Carmel River channel, 1930s, viewed from right bank

upstream from location of present Robinson Canyon

Road bridge. View upstream. Contrast this with figure 6,

essentially the same view, taken in 1918. (Pat Hathaway

Photograph Collection, Pacific Grove, California.)

Similar adjustments have been documented in other rivers in response to the absence of floods or the construction of upstream dams (Leopold etal . 1964).

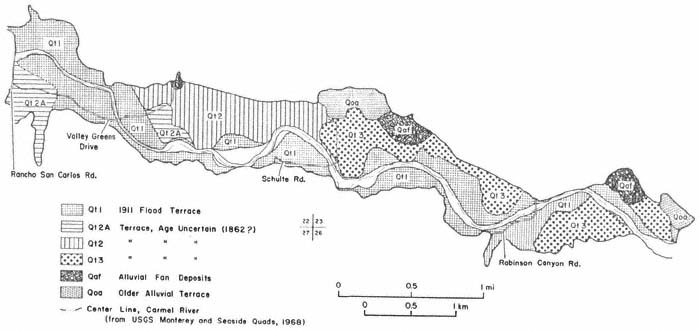

By 1939, the Lower Carmel had incised about 4 m. into deposits of the 1911 flood, leaving a 4 m. terrace. Some of this incision is visible when figures 6 and 7 are compared. The flat surface of sand and gravel to the right of the river in figure 6 is the 1911 channel floor. By 1918 (when figure 6 was taken), the channel had cut down about 2 m., and willows had begun to invade the low terrace. By the 1930s (when figure 7 was taken), the channel had incised about 4 m. The 1911 channel floor appears as the terrace in figure 7, with a farmed field and small building on it. This 1911 terrace can be confidently traced along much of the Lower Carmel on the basis of morphology and historic changes in course. Figure 8 shows the 1911 terrace (Qt1) and higher terraces. There is evidence that Qt2A may be the 1862 flood terrace, but otherwise the higher terraces are of unknown age.

Above the Narrows along the Middle Carmel, similar adjustments took place, but they occurred later. The aerial photos taken in 1939 show the scars of numerous anastamosing channels in the Middle Carmel. By 1971, most of these scars no longer appeared, as exemplified by the reach from Boronda Road to Robles del Rio (fig. 9). Accompanying this change in pattern was degradation of the bed. Sequential cross sections show 1.5 m. (5 ft.) of degradation under the Boronda Road bridge from 1946 to 1980.

By the 1960s, most of the Lower and Middle Carmel had developed a narrow, sinuous, well-vegetated course. It bears repeating that these

Figure 8.

1911 flood terrace and other Quaternary deposits of the Carmel River, from the Narrows to Rancho San Carlos Road.

(Based on reconnaissance-level study of aerial photographs, historic ground photographs, and historic changes in course.)

Figure 9.

Pattern changes, Middle Carmel River, from Boronda Road to Esquiline Road at Robles Del Rio.

(Data from aerial photographs of 1939 and 1971, Map Library, University of California, Santa Cruz.)

conditions developed only in the absence of major floods and, further, may have depended upon a cut-off of upstream sediment by the dams.

Additionally, before their suppression by European settlers, fires occurred regularly in the upper Carmel basin, periodically leading to vastly greater sediment yields. The accumulation of sediment in the Los Padres Reservoir after the Marble-Cone fire of 1977 was dramatic. The capacity of this reservoir decreased from 3,200 AF upon closure in 1947 to 2,600 AF in 1977, a loss of storage of 600 AF in 20 years. Consequent to the Marble-Cone fire and the high flows in the ensuing winter, the reservoir's capacity decreased to 2,040 AF by the end of 1978. Thus, in one year the reservoir lost 560 AF of storage.[4] This post-fire sedimentation rate was nearly 20 times greater than the pre-fire rate.

Prior to dam construction, all this sediment passed through to the Middle and Lower Carmel. It is probable that a wide, sandy channel would have developed in order to transport these high sediment loads. However, it is notable that the sediment contributed by the recent bank erosion has passed through the lowermost reaches of the Carmel (Valley Greens Drive downstream) without destabilizing that narrow channel. The stability of this lowermost reach may be due, in part, to the automobile bodies and riprap emplaced within the banks or to the extensive irrigating of streamside golf courses. Without these stabilizing influences, the channel might have widened in response to the higher load. Alternatively, such a narrow channel in its natural state, protected only by bank vegetation, may be able to pass these high loads without disruption of its existing geometry. In this latter case, the observed changes in channel pattern, form, gradient, and sinuosity may best be ascribed to recovery from the major floods of 1911 and 1914.