Nine

Conclusion

"Each in Its Ordered Place"

The ultimate statement of Faulkner on architecture, on urban design, on the took and layout of Jefferson, had come early in his oeuvre, in a single passage from Sartoris , a passage that leads centrifugally to the Square, the center, the navel, of Yoknapatawpha: They drove on and mounted the shady, gradual hill toward the square, and Horace looked about happily on familiar scene Then a street of lesser residencies, mostly new. Same tight little houses with a minimum of lawn Then other streets opened away beneath arcades of green, shadier, with houses a little older and more imposing as they got away from the station's vicinity; and pedestrians, usually dawdling Negro boys at this hour or old men bound townward after their naps, to spend the afternoon in sober, futile absorptions . (Fig. 91)

The hill flattened away into the plateau on which the town proper had been built these hundred years and more ago, and the street became definitely urban presently with garages and small shops with merchants in shirt sleeves, and customers; the picture show with its lobby plastered with life episodic in colored lithographed mutations. Then the square, with its unbroken low skyline of old weathered brick and fading dead names stubborn yet beneath scaling paint, and drying Negroes in casual and careless O.D. garments worn by both sexes, and country people in occasional khaki too; and the brisket urbanites weaving among their placid chewing unhaste and among the men in tilted chairs before the stores . (Plate 10, Figs. 92 and 93)

The courthouse was of brick too, with stone arches rising amid elms, and among the trees the monument of the Confederate soldier stood, his musket at order arms, shading his carven eyes with his stone hand. Beneath the porticoes of the courthouse and on benches about the green, the city

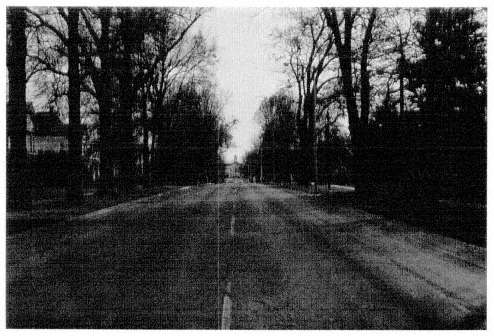

Figure 91

North Lamar Street, leading to Courthouse, Oxford, Mississippi (late 1950s).

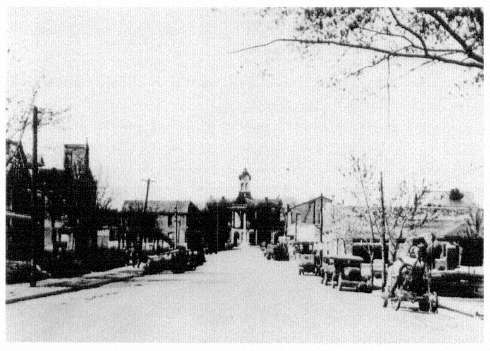

Figure 92

South Lamar Street, leading to Courthouse and Confederate Monument,

Cumberland Presbyterian Church on left, Oxford, Mississippi (1920s).

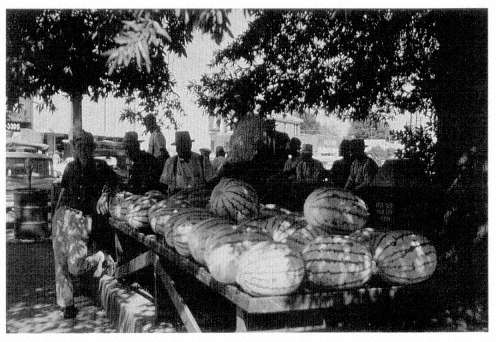

Figure 93

Vegetable Market, Courthouse Square, Oxford, Mississippi (late 1950s).

fathers sat and talked and drowsed, in uniform here and there. . . . When the weather was bad they moved inside to the circuit clerk's office (Fig. 94) [1]

For most of the twentieth century, traffic on the Oxford Square has drifted lazily to the right, but in the early twentieth century, one could go either counterclockwise to the right or clockwise to the left. Yet Benjy Compson, the retarded Compson son in The Sound and the Fury , had an aversion to the clockwise direction, a strong need for the anticlockwise course, perhaps a symbol of Faulkner's for Benjy's problems with time and history; perhaps too a suggestion that soon the whole town, and much of the universe, would be following the same course. Indeed the utterly idyllic portrayal of the Square in Sartoris contrasted markedly with the last two pages of The Sound and the Fury , where the dark decline of the Compson family erupted symbolically at the same Courthouse Square beneath the same Confederate monument. Still, it is significant that that brilliantly told tale of chaos and decline ends on the final page with a suggestion of order, a suggestion that Faulkner rendered in architectural terms: They approached the square, where the Confederate soldier gazed with empty eyes beneath his marble hand into wind and weather. Luster took another notch in himself and gave the impervious

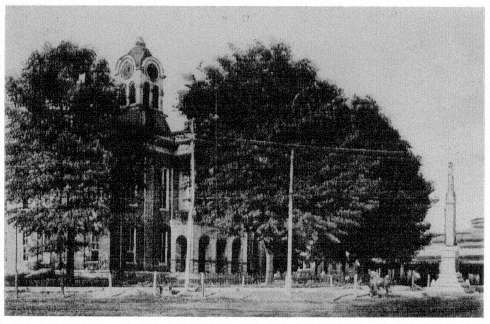

Figure 94

Second Lafayette County Courthouse, Willis, Sloan, and Trigg, architects

(ca. 1870; postcard, early twentieth century).

Queeme a cut with the switch, casting his glance about the square. . . . Ben sat, holding the flower in his fist, his gaze empty and untroubled. Luster hit Queenie again and swung her to the left at the monument .

For an instant Ben sat in an utter hiatus. Then he bellowed. Bellow on bellow, his voice mounted, with scarce interval for breath. There was more than astonishment in it, it was horror; shock; agony eyeless, tongueless; just sound, and Luster's eyes back-rolling for a white instant. "Gret God," he said, "Hush! Hush! Gret God!" He whirled again and struck Queenie with the switch. It broke and he cast it away and with Ben's voice mounting toward its unbelievable crescendo Luster caught up the end of the reins and leaned forward as Jason came jumping across the square and onto the step .

With a backhanded blow he hurled Luster aside and caught the reins and sawed Queenie about . . . while Ben's hoarse agony roared about them, and strung her about to the right of the monument. Then he struck Luster over the head with his fist. "Don't you know any better than to take him to the left?" he said. He reached back and struck Ben, breaking the flower stalk again. "Shut up!" he said "Shut up!" He jerked Queenie back and jumped down. . . . "Yes, sub!" Luster said. He took the reins and hit Queenie with the end of them. . . . Ben's voice roared

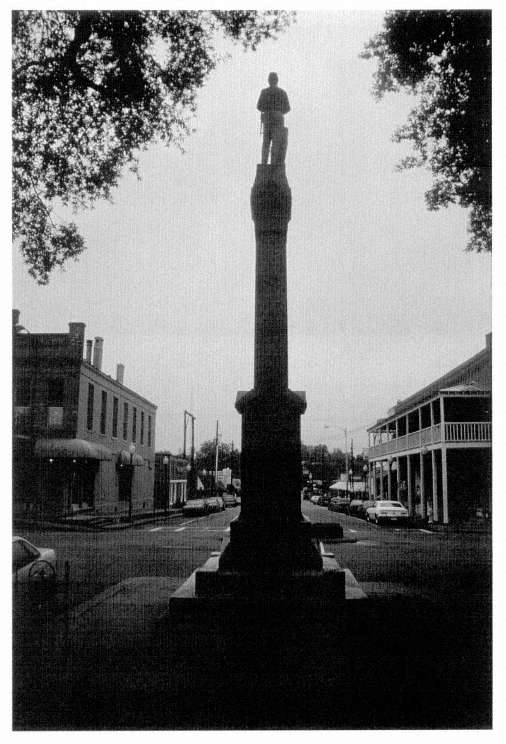

Figure 95

Confederate Monument, Courthouse Square, Oxford, Mississippi (1907).

and roared. Queenie moved again, her feet began to clop-clop steadily again, and at once Ben hushed. Luster looked quickly back over his shoulder, then he drove on. The broken flower drooped over Ben's fist and his eyes were empty and blue and serene again as cornice and facade flowed smoothly once more from left to right; post and tree, window and doorway, and signboard, each in its ordered place (Fig. 95). [ 2]

Thus, in work after work, Faulkner answered resoundingly the question he had posed long before in Mosquitoes in asserting and demonstrating that architecture was not only a part of life but an art that shaped and reflected its contours. However great the pain and joy of the comedy and tragedy of being alive , architecture was an art that was fundamental to life. Among all the vagaries of art and of life, it came closest to representing a sense of continuity between the past and the present. Indeed, it was—in Jefferson, the town—surely among the things that made up the quest for what Jefferson the man, Jefferson the architect had called "the pursuit of happiness."

Figure 96

Map of Oxford, Mississippi.

Figure 97

County Map of Mississippi (Ripley, 5; Oxford, 13; New Albany, 12;

Columbus, 30; Holly Springs, 4; Jackson, 45; Columbia, 57; Port Gibson, 48).