PART TWO—

AN INDUSTRY EMBATTLED, 1936–1938

The electoral results of 3 May 1936 startled even the victors. Not only had the Popular Front coalition of Radicals, Socialists, and Communists swept into power; for the first time Socialists had overtaken Radicals as leaders of the parliamentary left, and the PCF had emerged from electoral obscurity to become a major political party. Contrary to predictions, Léon Blum's Section Française de l'Internationale Ouvrière (SFIO)—the Socialist Party, and not the Radical Party—would form the new government, one squarely on the left. For aircraft workers, as for workers everywhere in France, the political climate suddenly brightened with the news that voters had elected the most left-wing government in the history of the Third Republic.

Just what steps the Blum government would take once in power, however, were unclear. Conflict between the three major parties in the Popular Front coalition simmered beneath the surface of electoral unity; the Popular Front program itself embodied unresolved tensions—between pacifism and defense, ambitious reform and tactical moderation—since the coalition hoped to appeal to both working-class and middle-class voters. Although euphoric over the victory, many left-wing supporters harbored fears that the new government would succumb to the compromises that had paralyzed Radical regimes in 1924 and 1932. Right-wing opponents feared the contrary—that Socialists and Communists would press for major structural reforms. To complicate matters, no sooner had elections ended than the contest over capital began: stock prices plummeted, the franc weakened, and influential investors, ignoring Blum's reassurances, began shifting assets into foreign accounts. Nor did the international climate offer solace. Two months earlier Hitler had transformed the military balance of power on the Continent by remilitarizing the Rhineland, a stunning initiative France and Britain had failed

to deter. By mid-May Mussolini had withdrawn Italy from the League of Nations and launched his war in Ethiopia. Meanwhile street violence in Spain brought France's other southern neighbor one step closer to civil war. To compound the sense of suspense, Blum refused to take power promptly, preferring instead to respect the customary month-long delay before assuming command; Albert Sarraut continued to govern as lame-duck premier.

In this atmosphere of hope, fear, and confusion, strikes began to break out—first in the aircraft industry, then in metalworking industries generally, and finally throughout the economy in the greatest wave of popular protest since the revolution of 1848. By the second week of June nearly two million workers had joined in the movement. The strikes, in turn, changed the political landscape. The CGT quickly blossomed into a mass organization as workers, now protected under the provisions of the Matignon Accord of 6 June, could finally join unions without fear of reprisal. By autumn the CGT had grown more than fivefold from the one million members it claimed at reunification in early 1936. Blum's government, moreover, in an effort both to capitalize on the strike wave and to restore public order, pushed through major reforms—paid holidays, collective bargaining, the forty-hour week—within a month of coming to power. No less important, the "social explosion" of June became a symbol: for workers, "June '36" became an emblem for solidarity, direct action, and the courage to stand up to the boss; for employers, it signified chaos, illegality, and left-wing insurgency. For both groups, the strike wave of June would long remain an emotionally charged point of reference.

This unanticipated series of events, from the elections of May through the strikes of June, revolutionized life in the aircraft industry. Aircraft workers suddenly emerged as a vanguard in the labor movement. Even while-collar employees cast their lot with the CGT. Employers, overwhelmed by the movement, had to reconcile themselves to negotiating matters that had previously been theirs to decide. The June strikes, moreover, colored how everyone responded to the next great upheaval in the industry—nationalization. In an effort to reorganize the industry, Blum's government opted to nationalize about 80 percent of the airframe sector. Under any circumstances such a policy would have aroused deep passions, but after June '36 people fought all the harder over what it would mean. From the summer of 1936 to January 1938 the industry remained a major center of controversy over issues as basic as wages and as complex as how to give labor a voice in newly nationalized firms. Even though the outcome of these conflicts still hung in the balance at the end of this period, it is now clear in retrospect that June '36 and nationalization made the aircraft industry a critical arena in the larger battle to redefine industrial relations under the Popular Front.

Three—

June '36

In the early spring of 1936 few observers would have predicted that aircraft workers would soon become the vanguard of a massive strike movement. To be sure, labor militance had revived in aviation since 1934. Plan I had strengthened the bargaining power of labor in many plants; the reunification of the CGT made it easier for militants to agitate in behalf of the new spirit of the Popular Front. Moreover, the brief strikes of 1934 and 1935 marked a sharp break with the quiescence of the past. Like militants in many other industries, aircraft militants had gone a long way to overcome the isolation they had suffered in the early 1930s, and the effort to mobilize support for the Popular Front—the meetings, marches, rallies, and electoral campaign—made them more visible to their fellow workers on the shop floor and in the local community. But these achievements were not unique. Militants in many industries were making headway in 1934 and 1935. What is more, aircraft workers lacked the strong unions and a track record of successful strikes that might logically have cast them for prominence in the sitdown movement of June '36. Their emergence as the catalytic force of labor protest in June '36 begs explanation. The first strikes in May 1936 offer clues, as does a look at the national negotiations that followed. These events point toward a number of factors that help explain why aircraft workers took the initiative in May and why the strike movement marked a turning point in the history of the industry.

The Initial Rebellion

Aircraft workers unwittingly began the great wave not in Paris, where one might have expected it, but in the port city of Le Havre at the mouth of the Seine. Workers in Le Havre had a colorful syndicalist past.[1] Revolutionary syndicalists there had won a strong following during the First

World War among seamen and dockers and in the metalworking and building trades. In 1922, even after the CGT schism and the strike defeats of 1920 had hobbled the labor movement nationally, a metalworking strike in Le Havre escalated into a week-long general strike that nearly became a municipal insurrection. Le Havre's workers soon fell into the same quagmire of trade union weakness that stymied workers throughout France in the 1920s. Still, when Louis Bréguet established a new factory for building seaplanes in Le Havre alongside the Tancarville canal, he recruited a local work force well aware of its political heritage. Although Bréguet's workers were no more unionized than aircraft workers elsewhere in early 1936, Communists and other militants of the revolutionary left continued to dominate the metalworkers union local as they had in the 1920s. Being a couple hours remove by train from Paris, they continued to enjoy a degree of independence from the Fédération des Travailleurs en Métallurgie (FTM), which, when it came time for taking initiatives, could sometimes be an asset for a trade union militant.

With hindsight we can now trace the immediate origins of the Bréguet strike to May Day, which in 1936 fell between the two rounds of the national elections and hence provided a fortuitous opportunity for left-wing militants to keep up momentum for the second electoral round. Nationally, the May Day mobilization proved particularly effective in metalworking and aviation; in the Paris region alone more than one hundred thousand metalworkers stayed away from work that day, and for the first time in fifteen years the Renault plant had to close for lack of workers.[2] At Bréguet's Le Havre plant a remarkable 90 percent of the work force failed to show up for work.[3]

In keeping with past habit, many employers throughout France answered the May Day demonstrations with reprisals at the factory level. Bréguet's factory director in Le Havre was no exception. On Saturday, 9 May, he fired two militants, ostensibly because they no longer were needed on the job; but as everyone knew, it was on account of their politics. Some workers also viewed the firings as a reprisal for another incident: a worker had embarrassed the personnel director (allegedly "a notorious member of the Croix de Feu") by rebuffing his efforts to sell right-wing newspapers to workers.[4] Whatever the chief motives of management, the firings provoked a revolt. Within hours militants from the local metalworkers union passed out leaflets at the plant inviting workers to an open meeting. That evening about seventy of the plant's five hundred workers gathered together and agreed to demand that the two workers be reinstated and that no others be fired. They also called for a forty-hour week in hopes of averting future layoffs, which, workers feared, could be in the offing.[5] No one called openly for a strike since police informers were assumed to be (and indeed were) at the meeting.

But buoyed by the May Day turnout and the Popular Front victory, a group of about twenty militants met secretly and decided to call a sit-in strike.[6]

By Monday morning a strike call had clearly spread through the plant. At nine o'clock all five hundred workers in the prototype and production shops stopped what they were doing, stood at their benches, and refused to work until the boss rehired the two men. The other 256 employees who served as inspectors, supervisors, engineers, technicians, and clerks remained aloof from the protest.[7] When Lechenet, the plant director, refused to negotiate, workers moved to occupy the plant until he yielded. Several strikers quickly became sentries to watch over equipment and guard against saboteurs. With a little nudging, young apprentices dashed home to alert parents that they might be spending the night in the plant. By evening a supplies committee, with support from families and local merchants, had brought blankets and food for the strikers' night-long vigil. Women strikers, however, went home for the night. Marius Olive, the second in command for the whole Bréguet firm, found workers so well organized that he later argued the strike had been thoroughly planned in advance. Sentries, he later reported, "were relieved every two hours, and veritable patrols, under the orders of a leader, made rounds through the factory."[8] The discipline of the strikers, their respect for plant property, and the ease with which they found supporters in town made the strike appear all the more sinister to employers.

However intimidating the strikers seemed to outsiders, they must have relied more on improvisation than advance planning. These militants had no experience with factory occupations. Indeed, it must have been rather unclear what it meant to "occupy" the workplace. To be sure, about a half-dozen factory occupations had occurred in France since 1920, and the great wave of Italian occupations in 1920 was well known.[9] The sit-down strike had become so common in the coal mines of Poland and Czechoslovakia in the early 1930s that French workers had come to refer to the tactic as a "Polish strike."[10] No doubt everyone at Bréguet understood the virtues of a sit-down: it precluded a lockout and made it tougher for scabs. Given the obvious danger of further reprisals and a chronic fear of layoffs, a factory occupation made plenty of sense. But it also posed new questions for workers as well as employers. Were strikers violating the property rights of employers? If so, what attitude would government officials take toward the strike? After occupying the factory, should workers try to run the plant on their own, as Fiat employees had done in Turin in 1920?

Although the strikers at Bréguet made no gestures toward taking over the production process itself, it became apparent immediately that the sit-in tactic gave them tremendous leverage in the negotiations that fol-

lowed. Director Lechenet had reacted swiftly, asking local officials to order police to evacuate the plant. Léon Meyer, the mayor of Le Havre, a Radical deputy and a former minister of the merchant marine, had a keener sense of the complexities of the situation. He balked at Lechenet's request. The strike delegates had, after all, said that if police rushed the factory, workers would scurry into the Bréguet 730 prototype that was sitting, fully fueled, in the large assembly hall for stationary tests—a situation that could, one militant recalled, "have serious consequences."[11] By early evening Meyer finally agreed to a modest show of force, dispatching one hundred local police and sixty gendarmes to surround the plant in hopes that their arrival alone would intimidate workers to leave. But the strikers held their ground. They insisted on talking directly with Marius Olive or even Louis Bréguet himself, and they asked the local subprefect to intervene on their behalf. Strikers had nothing to lose by holding firm as long as public officials restrained police from assaulting the plant. And restrain them they did. François Graux, the local prefect, sent an urgent telegram to the ministers of labor, the interior, and the air to explain that "workers appear firmly resolved to resist, and a serious collision would be feared if official force be used to expel them. The mayor and I think it useful to await results of negotiations between strikers and the administrateur-délégué before taking any action."[12]

Government officials proved pivotal in resolving the conflict. On the second day of the strike Prefect Graux arrived from Rouen and together with Meyer pushed Olive to yield. As Olive later recounted, the mayor told him that "in general he opposed forcing strikers and police or armed guards into confrontation. It seemed to me, on the contrary, quite easy to evacuate the factory, for I had the clear impression that most of the workers wanted to be free of this occupation and that in any case one could . . . block supplies and defeat the workers without the least risk of confrontation." But Prefect Graux told Olive that no lesser authority than Premier Albert Sarraut wanted the conflict ended and "did not want to see either the police or armed forces intervene." The prefect, moreover, urged Olive to negotiate not only with strikers but also with officials at the union level—a distasteful notion to Olive since he considered union militants to be outsiders to the conflict.[13] Indeed, a local Communist metalworker who did not work for Bréguet, Louis Eudier, had emerged a major spokesman for the strikers. But Olive had quickly run out of options. Pressured by strikers, on one side, and Prefect Graux, on the other, Olive agreed by early afternoon to submit the dispute to mayoral arbitration.

The mayor, meanwhile, easily won workers' approval of the arbitration agreement he proposed. It stipulated that the two militants be reinstated and that the plant director "organize the work in such a way as to

employ the largest number of workers, it being understood that management would remain the sole master of the organization"—subtle phrasing that affirmed management's authority yet implicitly recognized the possibility that without such assurances the employer might not be seen as the "sole master" of the shop floor.[14] The mayor then returned to his office, where he told Olive he would not require the firm to pay workers for the two days lost to the strike. With a settlement now clearly in reach, Olive departed for Paris, only to discover on his arrival that the mayor had in fact granted strikers two days' pay. The mayor's arbitration elated the strikers, who had won all their demands short of the forty-hour week, whereas it embittered Olive, who felt abused by workers and government officials alike.

The factory occupation not only enabled the strikers to prevail over Olive; it also elicited a burst of political energy in working-class Le Havre. Nearly a thousand friends, relatives, and fellow workers gathered outside the plant to express support for the protest and slip provisions into the shops. When the workers evacuated the plant and marched for nearly an hour to the city meeting hall, "the procession," as the local Communist newspaper described it, "was acclaimed by the population from the windows and on the sidewalks, the workers saluting them with raised fists as they walked and sang the International."[15] Two thousand metalworkers and other supporters joined the five hundred strikers at the meeting hall to hear the strike settlement read out loud, including a provision that if a slump in orders forced the factory to lay off workers, "the latter would have priority in the event of rehiring."[16] It was not a guarantee against layoffs, but it was the next best thing. In any event, local supporters seemed to recognize in the Bréguet victory something larger, a revival perhaps of what the local Communist press called "the spirit of the barricades of 1922."[17] At the very least, success confirmed workers in their optimism about a future under the Popular Front.

Strike success also brought immediate benefits to the metalworkers local of the CGT. Before the strike few people at Bréguet were prepared to assume the risks of union membership. Even so, when Lechenet fired the two militants, most workers felt that political rights had been violated and that their own security was at stake. Lechenet's provocation, anxiety over layoffs, and enthusiasm for the Popular Front helped militants and workers see eye to eye on the need for a strike. Union militants both inside and outside the company provided leadership, leaflets, and coordination, and nonunionized workers provided the enthusiasm and solidarity that had been missing for over a decade. After years of isolation, ironically, militants now had to move swiftly to keep up with workers. Accordingly, Ambroise Croizat, general secretary of the Fédération des Travailleurs en Métallurgie (FTM) and a newly elected Communist deputy, who had rushed down from Paris to attend the negotiations with the

mayor, congratulated the strikers at the meeting hall and urged them to join the union. Membership in the metalworkers local quickly grew, and the enthusiasm for the CGT spilled over into other local industries. According to one estimate, the CGT in Le Havre could claim only three hundred or four hundred members before the Bréguet strike and eleven thousand after it.[18]

One day after the strike in Le Havre an uncannily similar strike began in Toulouse. This time protest erupted at the Latécoère plant, where militants from the Dewoitine factory nearby had been struggling since 1934 to build a union. Again the immediate cause of the conflict stemmed from May Day. Since so many workers chose to observe this day of labor solidarity, Latécoère had to shut its doors for the day. Dombray, the personnel director, retaliated against workers by firing three militants for allegedly committing "serious mistakes" on the job.[19] On the morning of 13 May workers halted work, demanded that the militants be reinstated; then, fearing a lockout during lunch hour, they occupied the plant and sent a delegation to Ellen Prévost, the Socialist mayor of Toulouse. Prévost, like his counterpart in Le Havre, urged the factory director, Marcel Moine, to give ground.

Again as in Le Havre, May Day reprisals and the fear of layoffs had triggered the occupation, though additional grievances soon surfaced. According to one police spy, wage issues were "the real cause of antagonism" in the plant.[20] Yet that assessment seems too neat. The broadsheets that militants from the metalworkers local posted all over town condemned "the scandal of Latécoère factories" and cited "the inadequacy of the machinery, . . . the way workers were paid, . . . the harassment personnel had to suffer."[21] Not only wages but also a number of managerial practices gave workers the motivation to strike. If in Le Havre Bréguet workers used the issue of reinstatement to raise larger questions about layoffs, job security, and the organization of the workweek, at Latécoère workers used the firings to press for better wages, more respect on the job, and a fairer system of pay.

The strike ended more quickly than the one at Bréguet since Mayor Prévost intervened even more promptly than had Prefect Graux in Le Havre. By late afternoon Moine agreed to rehire the fired workers and recognize elected delegates as legitimate spokesmen for workers.[22] Moine hated to make these concessions; he believed that a majority of his workers had "no animosity toward the board of directors, the foremen, or management" of the firm and had participated in the strike quite indifferently.[23] But in fact he was up against two new developments that gave the strike its real punch—the enthusiasm with which so many nonunionized workers joined the protest, and the decisiveness with which local officials tried to settle the strike by backing the workers' de-

mands. Moine found himself squeezed in the same vise of labor militance and government pressure that had gripped Olive at Bréguet.

Victory swelled the ranks of the metalworkers local in Toulouse as it had in Le Havre. Nine days after the strike a police spy wrote to the prefect that management's effort to establish an antiunion association in the plant, the Amicale pour Combattre l'Action Syndicale, had utterly failed. Nearly all the workers at Latécoère, he reported, now flocked to the CGT local.[24] With Dewoitine's employees joining the union as well, aircraft workers were swiftly becoming a major constituency in the metalworkers local.

The events in Toulouse and Le Havre caught national business and labor leaders by surprise. Major metal industrialists who had gathered at the offices of the UIMM in Paris were taken aback by the strikers' ingenuity and the influence that government officials had had on the outcome. Feeling the need to do something in response, they agreed to survey how many other firms could fall victim to similar misfortune.[25] In the meantime CGT officials at the FTM applauded the victories. Yet behind their applause they seemed to harbor misgivings about local initiatives they had not controlled. On the one hand, labor leaders proclaimed these strikes as models that militants elsewhere might follow: "Whether in the north or the south, aircraft workers have just provided all metalworkers with a model of exemplary solidarity."[26] On the other hand, the bureau said little about the tactical breakthroughs and nothing about the larger issues strikers had raised, issues that conformed closely to those that the FTM had selected in April to form the basis of a new national propaganda campaign.[27] Local militants seemed prepared to blend themes from the FTM program with initiatives rank-and-file workers appeared ready to take by mid-May. But at the national level union leaders remained reluctant to encourage the new militancy.

National business and labor leaders inclined to view the two strikes as strictly local affairs were quickly disabused of the notion. On 14 May seven hundred workers occupied the Bloch aircraft factory in Courbevoie, an industrial suburb west of Paris. Unlike their comrades at Latécoère and Bréguet, the workers at Bloch struck purely to gain offensive objectives—higher wages, shorter hours, paid vacations, an apprenticeship program within the factory, a company cafeteria—rather than to reverse May Day reprisals.[28] Above all, these workers wanted Marcel Bloch to stick to his word. A few weeks before, he had already agreed to some of these demands after tough negotiations with Lucien Ledru, a young Communist militant who had emerged as the leading spokesman for Bloch's workers. But Bloch had done nothing to implement the agreement. After the Popular Front victory workers saw their chance to force his hand: they seized the plant. With supplies from fam-

ily and friends, and with donations of hot meals and money from left-wing municipal officials in neighboring suburbs, the strikers were able to spend the night in the factory and continue the sit-down into a second day. Shrewdly, the strikers also sent a delegation to discuss their grievances with L. O. Frossard and Marcel Déat, the labor and air ministers in Sarraut's cabinet; this hearing gave the strike an added measure of legitimacy.[29] What is more, several engineers and draftsman who had initially been trapped in their offices by the occupation subsequently chose to join the strike—an outcome particularly gratifying to Pierre Servanty, a militant who had been working hard to establish a CGT union in the plant for technicians and engineers.[30] By the afternoon of 15 May Lucien Ledru was once again negotiating effectively with Bloch, and the strikers soon achieved their principal aims—wage hikes, pay for the strike days, and recognition of the right to paid vacations.[31]

The victory at Bloch not only marked a shift from defensive to offensive demands; it also made the sit-down tactic visible in the Paris region, where aircraft workers were highly concentrated and where aircraft militants had gone furthest since 1934 to build a cohesive section for aviation within the FTM. Militants at Bloch belonged to a political network that included most of the major aircraft firms and many of the leaders of the Paris metalworkers unions. Even though the PCF remained reluctant to publicize these aircraft victories—L'Humanité began to report the first aircraft sit-downs only on 20 May—the lessons learned at Bloch were not lost on aircraft militants around Paris. On 20 May workers at Lioré et Olivier occupied their plant in Villacoublay, southwest of Paris, and after five days won a wage hike of one and a half francs an hour, the recognition of worker delegates, and the reinstatement of militants fired after May Day.[32] At nearby Issy-les-Moulineaux Nieuport workers made even greater gains on 21 May: a minimum daily wage, the recognition of worker delegates, the elimination of overtime, and—a major breakthrough—a forty-hour week.[33] On 22 May the strike movement spread beyond aircraft to the Compagnie Française de Raffinage, a refinery in Gonfreville near Le Havre.[34] The tally of protest was spectacular: within two weeks workers had won stunning victories in six occupations, five of them in the aircraft industry, where labor had fared poorly in the past.

Negotiating a Contract

During the last week of May factory occupations multiplied at an astonishing rate. The movement spread first within aircraft firms—to Farman, in Billancourt, and Dewoitine, in Toulouse—and to companies, such as Hotchkiss and Sautter-Harlé, that relied heavily on military contracts. On 28 May Renault followed suit; skilled workers in its aircraft

and armament shops played important roles in bringing France's largest factory into the strike movement. The next day workers at Gnôme-et-Rhône and at Salmson, both aircraft engine firms, launched strikes, as did workers at Citroën, Fiat, Caudron, and several other firms. By the end of the week two hundred thousand metalworkers had brought their plants to a halt, demanding that employers raise wages, cut hours, establish shop steward systems, and recognize the rights of workers to join unions. The furious movement of telegrams, delegations, union militants, police units, and working-class food and blanket platoons that had characterized the Le Havre strike two weeks before now occurred in dozens of plants.

As the strike wave grew, labor and employer organizations struggled to bring the situation under control. Labor and business leaders alike described the movement as a contagion, a metaphor betraying some discomfort, even in trade union officials, over so massive a grass-roots movement.[35] For national leaders of the CGT, the enthusiasm nonunion workers brought to their strikes, though welcome, created two kinds of problems. In plants where local trade union militants had helped initiate strikes, as appears to have been the case in most of the sit-downs in aviation, there was no guarantee that union militants would (or could) heed CGT directives to limit the strikes.[36] However, in work sites where strikes had caught local militants completely by surprise, it was all the latter could do to grab a share of strike leadership.

As a result, national leaders of the FTM had to maneuver between countervailing pressures. They could scarcely oppose a strike wave that offered them an opportunity to enlarge union locals and promote the demands the FTM had outlined only six weeks before. Communist officials in particular hoped to narrow the gap between the party and the working class and, if possible, monopolize the channels of communication between workers and the state.[37] The strike wave, moreover, created an opportunity to pressure the new Popular Front government to legislate its program of social reforms in rapid order once Léon Blum took power. But at the same time FTM officials felt the need to contain the strike movement lest it outflank the national leadership and turn against them, as had happened in the Paris metalworkers' strikes of June 1919.[38] National trade union leaders, both Communist and otherwise, feared strikes they could not control, especially at a time when the unity of the Popular Front—and its middle-class support—meant so much to the left. To escape this dilemma, the FTM pursued a two-pronged strategy: it called for national negotiations with employers to establish a collective contract, a tactic that would both build on the momentum of the movement and channel it into an activity the Federation could control; and it urged employers, and implicitly the workers themselves, to see the

strikes as a movement for modest economic demands.[39] When on 28 May the Sarraut government moved to intervene in the crisis, the FTM's strategy seemed to pay off: Air Minister Déat brought together representatives from the FTM and the aircraft employers' Chambre Syndicale, and Labor Minister Frossard did the same with leaders of the UIMM.[40] Negotiations appeared imminent.

Besieged by their workers within plants and pressured by the Air Ministry to negotiate, industrialists in aviation were finally forced to respond collectively to the movement. On 28 May Henry de l'Escaille, president of the Chambre Syndicale, addressed his colleagues. Having met with Sarraut and Frossard, he felt employers in the aircraft industry ought to "collaborate from now on in the drafting" of a collective agreement.[41] A notion as revolutionary for the industry as a collective contract no doubt divided the Chambre Syndicale. To some members, like de l'Escaille, such a step may have seemed unavoidable under the circumstances. Even Fernand Lioré, rarely a progressive voice on labor matters, suggested that an effort under way to establish a collective agreement at the Arsenal d'Aéronautique, a state-run facility in Orléans, might provide a framework for broad negotiations. The Chambre Syndicale, however, found its way to a more conservative strategy—to oppose a separate contract in aircraft and argue instead for a single metalworking contract negotiated by the UIMM.[42] With this goal in mind, aircraft officials urged Alfred Lambert-Ribot, head of the Comite des Forges, to push the government into suspending talks scheduled for separate aircraft negotiations and hence divert the battle in aircraft into a conflict over contracts in metalworking as a whole. Aircraft employers, in short, sought refuge within the well-armed fortress of the UIMM.

Events in the first week of June only deepened the conflict. On 3 June talks between the FTM and the UIMM collapsed after employers insisted that workers evacuate plants before negotiations could resume. Meanwhile a second wave of sit-down strikes spread throughout France. By the end of the week more than a million employees—not just in industry but also in commerce, insurance, and banking—had joined the movement. In aircraft, too, strikes broke out in a number of Parisian and provincial plants that had escaped the first wave of May. Aircraft technicians and office employees, moreover, began to ally more openly with workers. At Morane-Saulnier in Puteaux and Villacoublay, at Hanriot in Bourges, and at the Bréguet plant in Villacoublay technicians took active roles in their strikes; at Bourges in particular they promoted grievances of their own.[43] The movement spread out into the countryside and up into the white-collar strata of the industry, and much the same happened in other industries.

It was in an atmosphere of widespread panic that Léon Blum took decisive action upon assuming the premiership. Addressing parliament on 6 June, he announced a legislative program to establish the forty-hour week, collective bargaining, and two-week paid vacations for all workers in France.[44] The following day, at the secret request of employers now frightened by events, Blum negotiated the Matignon Accord, which granted workers across-the-board pay increases, the right to join unions, and the right to elect shop stewards in plants with more than ten workers. In a France that lagged far behind many other countries in labor legislation, Matignon was a stunning breakthrough for the CGT. Blum's efforts, however, failed to dampen popular protest, as the strike movement spread even further on 8 and 9 June. Since the Matignon Accord lacked the status of law, and since many employers, including Lambert-Ribot, president of the Comité des Forges, expressed misgivings publicly about a deal struck under duress, workers felt they had to continue their strikes until their own employers met their demands. As much as national officials in the CGT wanted to bring the strikes to a close, they still had too little influence with strikers to do so. Even in metalworking, where union officials and the PCF had some success in cooperating closely with rank-and-file strikers, relations remained tense between local strike committees and FTM leaders.[45]

Aircraft workers, moreover, had reason to believe they could gain more than had been won at Matignon. The accord, after all, had endorsed the principle of collective contracts, leaving the door open for workers and employers in individual branches and locales to negotiate. With virtually the whole of Parisian aircraft construction shut down by the movement, and many provincial factories as well, the pressure on employers was greater than ever to return to negotiations with aircraft militants. On 8 June aircraft manufacturers found themselves cornered into just the kind of separate negotiations they had tried to avoid the week before.

Aircraft workers had a further incentive to hold out for a collective contract, for by finally coming to power, Léon Blum had strengthened their hands in two ways. First, the Popular Front victory had made the nationalization of the industry an imminent possibility. Blum dispelled any doubts of this on 5 June when he announced to the Chamber of Deputies that he would present legislation to nationalize the arms industry.[46] Just what shape such a reform would take and how it would affect a sector as complex as the aircraft industry remained unclear. Even so, the government lent legitimacy to notions of state-controlled industry, however vaguely defined, and thus gave workers and government officials alike a potential weapon to wield against management. Some mili-

tants even began linking notions of nationalization to visions of workers' control. When, for example, seven hundred strike committee delegates from Paris metalworking industries met on 10 June, they rejected FTM plans to accept a compromise contract. Instead, they voted to issue employers an ultimatum: either agree to the contract with minimum wage guarantees, or the strikers would call for "the nationalization of the factories on strike and of those working for the state, operated by technical personnel and workers under the supervision of the ministries involved."[47] Simply by coming to power with a commitment to implement the program of the Popular Front, Blum tacitly allowed the specter of expropriation to take a seat at the negotiating table.

Second, Blum's electoral victory brought Pierre Cot back as air minister, and Cot had few qualms about intervening in workers' behalf. His brief tenure at the boulevard Victor in 1933 had demonstrated his independence from the builders. He still had the air of the brash Young Turk. Moreover, the events of February 1934 had inspired him to become a major architect of the Popular Front strategy; though still a Radical, Cot felt even more resolutely on the left than before and was committed wholeheartedly to revitalizing the industry and improving its labor relations. Aircraft workers, then, had the advantage of an air minister sympathetic to collective bargaining in the industry.

With strikers showing more determination than ever, and with Pierre Cot bent on forging a contract, aircraft employers finally succumbed to an agreement on the night of 10 June. Minutes of this pivotal meeting, held at the Air Ministry itself, have not survived in the archives; but an embittered Marius Olive, administrateur-délégué at Bréguet, apparently handed over a copy of these minutes years later to judicial officials at the Procès de Riom, and he interpreted them for the court:

You will see [in the minutes that] from the beginning of the negotiations M. Cot, the air minister, had in the presence of the workers withdrawn from employers any possibility of discussion by threatening them with requisitioning their factories. . . . The workers used this threat several times and reminded the minister of it, especially at the moment when the issue of wages in the industry was raised. On the night of 10–11 June Cot pressured the Chambre Syndicale directly to yield to workers' demands.[48]

However biased Olive's version of the meetings may have been, it reveals how employers felt cornered into making concessions. Cot no doubt played a key role in getting a settlement.

The contract that workers won through these negotiations marked a sharp break from the autocratic framework that had governed labor relations in the industry. The agreement was far from simple; its thirty-two articles and detailed wage schedules testified to the determination, shared by both workers and employers, to minimize the need for fur-

ther debate. This level of specificity implicitly revealed how much distrust had surfaced in the strike and how rapidly both sides had come to depend on state-supervised negotiations to flesh out details. Unlike in Britain, where trade unionists had kept government officials out of the collective bargaining process and continued to do so, in France CGT militants were willing to use the influence of sympathetic state officials to full advantage.[49] The June talks with Cot, moreover, appeared to validate the approach.

This first collective contract in aircraft, which applied only to workers in the Paris region, granted workers precisely the changes in wages and working conditions they had most hoped to win by their strikes.[50] They could now join unions without fear of reprisal; militants who had once been fired for their political activities could now, according to the contract, reclaim their old jobs. Employers, moreover, were now obliged to give workers at least two weeks of paid vacation and pay overtime rates ranging from 33 to 50 percent above normal hourly wages. The contract also required employers to establish a delegate system. In this respect the contract fell short of the radical reforms many militants sought in a new system of workers' representation; the plan mandated by the contract called for too few delegates—one for a firm of fifty workers, two for two hundred fifty workers, three for a thousand workers, and so on—to allow workers to convert the delegate system into the more substantial shop steward networks that many workers wanted. Nor could militants be sure that the new delegate system would work to their advantage since it gave employers as well as workers a new channel of communication within the plant; it provided no guarantees that delegates would be faithful to the union. Still, the new delegate system at least legitimized the notion of shop floor representation and gave delegates a chance to voice grievances on a regular basis. The contract, then, offered employees genuine reforms in an industry where paternalism and repression had long prevailed.

It was the wage schedules, however, that made the news of the contract reverberate throughout France. Of all the issues under discussion, wage questions had caused negotiators the greatest anguish, for with wage hikes the shift in political power in the industry took its most tangible form. When averaged by skill category, the new wages stood well above those that Parisian metalworkers had earned during the first quarter of 1936—22.7 percent higher for skilled workers, 26.7 percent higher for semiskilled workers, and 25.9 percent for unskilled laborers.[51] The new wages guaranteed by the contract were higher still in the engine-building sector, where most skilled workers now would earn 8.40 francs, semiskilled workers 7.50, and unskilled laborers from 6.00 to 6.90 francs. Pieceworkers, too, won guaranteed minimum wages and the

right to draw salaries during lulls in production. The contract even prohibited employers from reclassifying workers into lower ranks to cut costs. In short, it made aircraft the most highly paid sector in metalworking and diminished the capacity of employers to use wages to discipline workers on the shop floor.

The new wages also reduced the differences between pay scales for various kinds of workers in the industry. Under the new contract semiskilled men earned 82 percent of what skilled men received, compared to the 75.5 percent semiskilled men earned at Farman in 1927. Semiskilled women earned 80 percent of the wages of semiskilled men, a slight improvement over the 77.5 percent that semiskilled women earned at Farman in 1927. An unskilled laborer still earned only 68 percent of a skilled worker's wage. To be sure, wage differentials remained. The contract maintained nineteen separate wage distinctions—testimony to the desire of skilled workers to maintain traditional skill differentiations in the industry. Thus the wage structure reflected both the continuing predominance of skilled workers, whose interests were fully protected, and the spirit of the Popular Front, which sought to give special relief to lower-paid workers.

By winning such a favorable contract, aircraft workers inspired other strikers in metalworking industries. In this respect they repaid the debt they owed the strike movement as a whole for strengthening their own bargaining position. The big industrialists in the UIMM now found it more difficult to avoid making some concessions along the lines their colleagues in aviation had had to offer. The aircraft contract also gave rank-and-file metalworkers an incentive to keep the pressure on their own representatives in the CGT. As Maurice Roy, a national secretary for the FTM, later admitted, "On 11 June a great divergence emerged [in the wage talks] as a collective contract for workers in aviation had just been signed with serious advantages on minimum-wage rates."[52] The aircraft contract, in short, brought the crisis in Parisian metalworking to a head by 11 June. Rumors surfaced that some metalworkers wanted to pour out of the factories and into the streets of central Paris. Faced with the renewed danger of losing control over events, Maurice Thorez, the general secretary of the PCF, appealed unambiguously for a truce. "We still do not have everyone in the countryside behind us," Thorez said. "We even risk alienating some of our bourgeois and peasant supporters. So it is necessary to know how to end a strike when the goals have been obtained. It is necessary to compromise even if all the demands have not been met, as long as we have won the most essential demands."[53] With the Popular Front parties all exerting their full political weight for a compromise, the FTM and the UIMM settled on a metalworking contract on 12 June, one that forced concessions from employers but fell

short of the wage rates aircraft workers had won. As in aviation, the metalworking contract was a milestone. Still, some militants felt the PCF had given ground too soon, such as J. M. Bertin, a Communist dissident at the far left of the PCF, who thought that metalworking employers could have been squeezed for more. "This is shown especially," Bertin wrote, "by the better agreement won earlier on wages and hiring by the aircraft workers, who make up the avant-garde."[54]

When Parisian aircraft workers evacuated their factories after 10 June, they emerged as an elite within the trade union world of French metalworking. Suddenly these workers enjoyed not just the material protections of the new contract but also the prestige of securing the best pay scales in France. As a result, aircraft locals became vibrant, burgeoning unions. The strength of labor solidarity, of course, would continue to vary a good deal from plant to plant, particularly in provincial cities where the struggle to win contracts parallel to the Parisian agreement continued through June, with mixed results.[55] Still, for most workers, the balance sheet of the strike movement was clear: the aircraft industry was no longer a backwater for the labor movement, a bastion of employer traditionalism. By June it had become center stage for labor reform under the Popular Front.

The Sources of Militance

The question remains why workers in one industry consistently served as a vanguard in the strike movement, from the first factory occupation at Le Havre through the negotiation of collective contracts. A look at what happened in the strikes and what workers wanted points to four features of the aircraft industry that were crucial in encouraging worker militance. The first was the peculiar character of the labor market on the eve of the strike. The growth of government orders since 1934 had increased the demand for labor, if not dramatically, at least more than in most other industrial sectors. This increase, in turn, had strengthened labor's power to bargain. At the same time, however, deflationary policy in late 1935 and early 1936, coupled with uncertainty about what would follow Plan I, jeopardized the expansion of the industry. These developments, in fact, renewed the prospect, and in a few plants even the reality, of layoffs.[56] This unusual sequence of changes—a two-year trend toward tightening the labor market followed by several months of anxiety over layoffs—ripened the industry for protests over issues of job security. When employers fired militants for observing May Day in 1936, aircraft workers were particularly sensitive to the implications. The volatility of employment made these workers keen to reduce the power employers had traditionally enjoyed to reassign, reclassify, and eliminate employees

as they pleased. A number of the demands aircraft workers made in their strikes—reinstatement, union rights, a shorter workweek, union control over hiring and firing, paid vacations to replace the annual unpaid factory closing common in the industry—all betray a yearning for job security.

The second feature of the industry that helps account for strike militance was the moderate strength of the unions. Stronger unions might have stifled local initiatives since the national leaders of the PCF and the newly reunified CGT feared strikes they could not control. Weaker unions would have made it more difficult to launch the movement since strikers depended on local militants for leadership and logistical support. Many aircraft plants had the right combination—on the one hand, workers who in the political euphoria of May 1936 were eager to win greater security for themselves, and on the other, experienced militants who were established enough to lead strikes, orchestrate sit-downs, and marshal support from sympathetic municipal officials but were not yet powerful enough to enforce the discipline of the national federation. The crucial tactical decisions—daring to occupy plants in May and holding out for a separate contract for aviation in June—might well have been compromised had the FTM had greater control over the rank and file.

The strike wave in aircraft was neither a purely spontaneous rank-and-file movement nor a scheme masterminded from above. Rather, the strikes involved a continuous interplay between strikers at the local level and national leaders in Paris, who responded to local initiatives improvisationally, without a clear sense of strategy.[57] From the first strikes at Bréguet and Latécoère through those at Bloch, Farman, Renault, and other aircraft and metalworking plants in Paris during the last week in May, local Communists and revolutionary syndicalists agitated for strikes in much the same manner as they had as CGTU members or as isolated revolutionaries during the politically lean years before 1936. But if local militants were essential to the success of the first strikes, they were not the plotters of a large-scale movement. As one police official wrote at the time, although local Communist militants "found themselves among the most active organizers" of individual strikes, "one must recognize that the Communists in the unions were the first to be surprised by the movement ."[58] Once the strike wave became nationwide, local militants had to maneuver amid sometimes-contradictory tasks of encouraging rank-and-file militancy and keeping the movement under control in the interest of FTM strategy. Local militants, in short, played crucial roles in giving strikes their initial coherence and direction, even as these same militants proved essential in channeling the movement into a contest over a collective contract, organizing plant evacuations after 10 June,

and in at least one case (at Latécoère in Toulouse) discouraging a strike in early June that militants deemed ill advised.[59] Most militants handled this balancing act effectively, as the success of the movement in aviation demonstrates. Moreover, had local militants been more out of step with the rank and file, or had they alienated their fellow workers in the course of these events, the latter would probably not have stampeded into the CGT as they did in the weeks that followed. The most palpable tensions within labor during the strike movement were not between local Communist militants and the rank and file but rather between strikers at the local level and national leaders of the FTM and the PCF who were eager to get a settlement.[60]

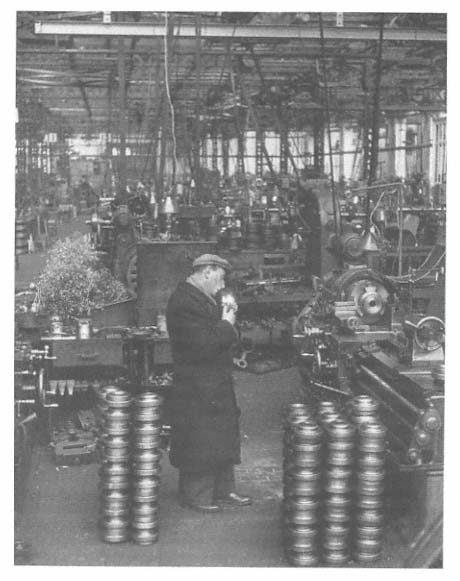

A third feature of the industry that helped shape the strike movement was the composition of the work force. Many of the skilled metalworkers who predominated in both serial production and prototype building identified with the culte du métallo , the sense of craft prowess that came with years of experience in the metalworking fraternity. Moreover, the self-esteem some workers felt from being associated with aviation, and which employers encouraged, could also enhance a feeling of shop floor camaraderie, especially in the politicized atmosphere of the Popular Front era. This ethos of solidarity made skilled workers in aviation particularly attentive to questions of shop floor autonomy and managerial control. Thus, the intensity of the strike movement in the industry stemmed in part from the willingness of skilled metalworkers to raise grievances about the quality of life on the shop floor.

Strike demands conveyed these concerns. From the first strikes of May to the full-scale shutdown of Parisian aircraft plants by the end of the month, aircraft workers called attention not so much to questions of pay, though these, too, were important to them and figured prominently in negotiating the regional contract; rather, questions of workers' rights and managerial authority lay at the heart of most strike demands. Take the grievances, for example, that workers at Dewoitine presented to the firm on 27 May. These strikers called for the recognition of their union, the establishment of shop floor delegates elected by workers and sponsored by the union, the right of two union representatives not employed at the plant to participate in discussions between management and the delegates, and the creation of a committee to oversee hiring examinations. In addition, workers demanded specific changes in shop operations—improvements in machinery, the elimination of piece rates for certain kinds of machine work, and time "to clean and grease machinery every Saturday morning."[61] These workers rose in revolt not against the rationalization of the work process, which plagued workers in munitions and automaking, but against rigid rules and irrational encumbrances that irked them on the job. Similarly, at the Hanriot plant in

Bourges workers called for the elimination of the noontime supervisory check and demanded that more time clocks be installed instead.[62] These workers, who preferred an impersonal time clock to a foreman's harassment, were rebelling against arbitrary authority, not time discipline per se. The collective contract Parisian aircraft workers won on 10 June, with its nineteen wage categories and its detailed regulations for giving shop delegates a say in their factories, conveyed a similar concern for replacing the authoritarianism of the patron with something akin to a social contract. What troubled skilled workers was the failure of management to run plants effectively, modernize equipment, treat employees justly, and include them in making decisions in the plant. In aviation, at least, the strike wave was a rebellion against employer autocracy, a struggle to make the aircraft factory a more secure and sensible place to work.

Not that these issues alone fueled the movement. The festive spirit that emerged during the Bréguet strike appeared in most of the sit-downs. To break the monotony of the daily routine, to mobilize family and friends in supply operations, and to become part of a historic upheaval with unknown consequences created an air of excitement that in itself helped to sustain the movement. Aircraft workers, moreover, like their counterparts in other industries, discovered what Simone Weil called joy—"the joy of entering the factory with the friendly permission of a worker guarding the door, . . . of seeing so many smiles, so many words of fraternal welcome, . . . of running freely through workshops where one had been riveted to a machine, of forming groups, chatting, snacking, . . . of listening not to the pitiless roar of machines, a striking symbol of the harsh necessities to which one yielded, but to music, singing, and laughter."[63] Workers experienced the pleasures and frustrations of reconstituting a community in the workplace for purposes of their own—talking politics, plotting strategy, swapping stories, staging plays and mock trials, playing soccer, dancing, singing, drinking, flirting, fighting, and otherwise passing the time.[64] Some of this enthusiasm fed on the nervous energy that came from fear: Might the gendarmes attack the plant after all? Might some of the foremen who were members of the Croix de Feu try to sabotage the strike? Might the strikers succumb to disorderly conduct and ruin their own strike?[65] Uncertainty added to the intensity of the experience, as did the sense of adventure. Henri Jourdain recalled, decades later, the thrill of "traversing Paris in cars that were requisitioned by the strike committee at Renault and decorated with red flags, honking, barely stopping for traffic lights, while the cops cleared our path to get us to the regional headquarters of the métallos union."[66] Workers, of course, relished a respite from the discipline of foremen, clocks, and machines. Not for nothing did the demand for paid holidays, first fought for and won in the Bloch strike at Courbevoie,

emerge as a popular objective that caught even the CGT by surprise.[67] Yet in analyzing the strikes in aircraft, it would be an error to see the playful side of the movement as its essence or argue that workers sought more to escape than to transform the factory.[68] Though escape may have been a crucial motive in industrial branches where rationalization was more fully advanced, in the aircraft industry workers' interest in wage hikes and vacations complemented—and did not substitute for—a yearning for greater power in the workplace.[69]

A fourth factor helping account for aircraft worker militancy was the proximity of the industry to the state. Aircraft workers took the initiative in part because they were better prepared than other workers to understand just what the electoral victory of the Popular Front could mean for them. Since the early days of aviation the state had been the leading customer for the business. In aviation, as in shipbuilding, mining, and railroads, it was no secret that government officials could influence the way employers dealt with their workers. Moreover, with Plan I everyone in aviation had become acutely aware of the leverage that the Air, Labor and Finance ministries could exert in the industry. The air minister himself had been decisive in settling a major strike in 1935 at Duralumin, the major supplier of special metals to the aircraft companies.[70] When Dewoitine threatened to lay off one hundred workers in late 1935 in Toulouse, labor militants and local business leaders raised a ruckus with deputies and senators to push the Air Ministry to redistribute its orders.[71] No doubt about it: aircraft construction was a political affair, and when the Popular Front coalition came to power with a platform that called in vague terms for the nationalization of war industries, everyone knew that the balance of power in aviation might change dramatically. As Simone Weil wrote at the time in analyzing the strike wave:

Trade union unity was not a decisive factor. Of course, it was a great asset, but it weighed more heavily in other branches than Parisian metalworking, where a year ago there were only a few thousand in the unions. The decisive factor, we have to say, was the Popular Front government. Yes, one could finally—finally!—go on strike without [fearing] the police and gendarmes. But that held true for all branches. What really counted was that the metalworking factories nearly all worked for the State and depended on it to balance the books. Every worker knew it. Every worker, in watching the Socialist Party come to power, had the feeling that in confronting the boss, he was no longer so weak. The reaction was immediate.[72]

In this respect the strike movement in aviation was, above all, a response to political events. Left-wing rule suddenly enabled workers in an industry like aviation to challenge the autocratic authority of their employers with a sense of optimism. Although other factors—the peculiar nature of the labor market, the moderate strength of the unions, and the skilled

character of the work force—made aviation ripe for a strike movement, it was the dependence of the aircraft companies on the state that made workers responsive to the new political climate. In no other industry was the clash so clear between employers, who were used to exercising unfettered authority in their factories, and workers, who were suddenly empowered by the victory of the Popular Front.

The Consequences of June '36

It would be hard to overestimate the importance of the events of May and June 1936 for the subsequent development of labor relations in the industry. For one thing, the outcome of the aircraft strikes made workers and employers even more aware than before of how influential the government had become in their industry. The first strikes in May certainly confirmed that state officials could be pivotal. When local officials lent support to strikers in Le Havre, Toulouse, and Courbevoie, and when national officials gave workers a sympathetic hearing, workers readily grasped the implications. The role of the Air Ministry in negotiating a settlement, first under Déat and then more dramatically under Cot, lent credence to the view that state intervention would enhance workers' power in the industry. It was this notion that encouraged militants to raise the issue of nationalization when contract talks threatened to stall. To be sure, government efforts to placate strikers may have frustrated the few genuine revolutionaries who hoped the June strikes might precipitate a larger crisis. Most workers, however, proved willing to settle for the lesser revolution that the collective contract entailed; and few radicals of the far left, not even the Pivertists in the left wing of the Socialist Party or Pierre Monatte's group of revolutionary syndicalists, belittled the achievement. These gains served to enhance the belief that state officials, sufficiently prodded from below, could change life in the industry for the better—an attitude not unique to the aircraft industry. Simone Weil found workers in metalworking as a whole around Paris optimistic about state intervention. "One hears it said [among metalworkers]," she reported in June, "that if certain bosses close their factories, the State will reopen them. They do not wonder for an instant if they will be able to make [the factories] function well. For every Frenchman the State is an inexhaustible source of wealth."[73]

At the same time government support for workers' demands terrified employers, who since 1934 had become increasingly inept in cooperating to solve basic structural problems in the industry. Some employers in aircraft, though not all, condemned the refusal of the state to evacuate plants forcibly and hence uphold the rights of property.[74] No one in management, however, viewed lightly the pressure state officials applied

to accede to workers' demands. Employers and their most sympathetic supporters in the state engineering corps blamed Pierre Cot in particular for the two results that management believed to be catastrophic for the industry—a pay scale boosting aircraft wages above metalworking norms, and a decline of managerial authority on the shop floor. Marius Olive, administrateur-délégué at Bréguet, asserted that in business circles "the wages for a cleaning woman in aviation"—4.80 francs an hour, not a great deal of money but well above average for custodial work at the time—"had become a kind of slogan in industrial circles," a shorthand for criticizing overscale wages throughout the aircraft sector.[75] At Riom Pierre Franck, a state engineer, would later charge that "the attitude of the [air] minister . . . strongly encouraged the worker representatives to be masters of the factory. They continually harassed management with demands of all kinds."[76] Similarly, Jean Volpert, another state engineer, would argue that when Cot "openly reprimanded the employers of the occupied plants in aircraft in front of the labor representatives," he inspired "anarchy" in the factories.[77]

Such charges were hyperbolic; yet there was no denying that the Chambre Syndicale took a beating in June when faced with the combined force of factory occupations and government pressure. Negotiations for a regional contract in Paris revealed how much autonomy employers had lost since the early 1930s. In the face of a strike movement of such magnitude and an Air Ministry determined to settle the conflict, the builders could not repel the drive for a separate contract in the aircraft industry. Munitions manufacturers, tank builders, and other defense contractors fared better in the crisis since they at least fell within the less costly contract for metalworking as a whole. Aircraft employers, in contrast, by signing a separate contract, now found themselves saddled with higher wages, more isolated from their colleagues in metalworking and the UIMM, and more vulnerable to state pressures than before.

If the strike movement crystallized the way workers and employers viewed the state's role in the industry under the Popular Front, it also had a second consequence no less significant: it strengthened the Communist wing of the CGT in aircraft factories throughout France. Communist militants such as Lucien Llabres in Toulouse and Lucien Ledru in Courbevoie were quick to assert their leadership in the aircraft strikes, and they were rewarded for their efforts in the weeks that followed as their fellow workers rushed into metalworking locals. The significant progress that unitaire militants had made in aircraft plants in both Paris and the provinces between 1934 and the spring of 1936 now enabled Communist militants to reap the unexpected harvest of the massive growth of the CGT. By having outcompeted their ex-confédéré rivals in aviation for local influence during the crucial years of 1934 and 1935,

ex-unitaire (and usually Communist) militants emerged as beneficiaries of union growth at the local level. By late June most aircraft workers, like metalworkers everywhere in France, had joined the CGT; by September membership in the metalworking federation, the FTM, would mushroom to six hundred thousand, quite a spurt from forty thousand the previous March.[78] Furthermore, whereas the stampede into unions also occurred in most other industries, the triumph of the regional contract in Parisian aviation made CGT locals all the more attractive to aircraft workers since the CGT would now oversee the application of the contract in the factories.

Communist militants outmaneuvered their ex-confédéré rivals not only because they asserted themselves effectively during the strike movement or because they had already profited from the PCF's shift to a united-front strategy in 1934. They also cashed in on the PCF's rising fortunes at the national level. The Popular Front elections of May 1936 established the PCF as the dominant political force in the red belt of Paris, which, despite the efforts of the Air Ministry to decentralize the industry, was still the heartland of airplane and engine construction. The working-class suburbs of Paris now sent Communist Party militants to seats in parliament as well as to municipal councils and mayorships, which in turn enabled the party to offer their working-class constituencies the services of an up-and-coming political machine. Aircraft workers in the Paris region now encountered Communist Party posters, leaflets, newspapers, and militants in their neighborhoods as well as at the factory gate.

Of course, party militants in Toulouse, Bordeaux, and other provincial cities with aircraft factories did not reap the direct benefits of the red belt revolution, but they did profit from the rising prestige of the PCF. Perhaps more important, they prospered from the earlier failure of the Socialist Party, even in a strong SFIO town like Toulouse, to build a solid organizational base in the metalworking industry. Of the twenty-five Communist factory cells that flourished in Toulouse after June '36, seventeen were in aviation (and five in railroads).[79] Of the major provincial aircraft-building centers, only Saint-Nazaire and Nantes had metalworkers locals with a decidedly Socialist orientation. But even there Communist militants made inroads in the wake of June '36; at Loire-Nieuport more than fifty workers joined the party.[80] Furthermore, by November 1936 Communist militants had established a tight grip on the national leadership of the FTM.[81] Their power, in turn, gave factory militants in the PCF greater clout locally. To be sure, the rivalry between Communists and non-Communists on the shop floors of aviation would continue after 1936, as we shall see. Few workers, moreover, actually joined the PCF, certainly no more than 10 or 15 percent during the summer of

1936.[82] Yet if most workers kept some distance from the party, they nonetheless helped make their industry a CGT stronghold, thereby narrowing the gap between aircraft workers and the PCF. In all the major centers of aircraft manufacturing except Nantes and Saint-Nazaire, Communist militants emerged from June '36 with enough strength to remain the leading spokesmen in the blue-collar ranks of the industry for the rest of the 1930s.[83]

The strikes also enabled employees to narrow a gap of a different kind—the gap between blue-collar and white-collar workers. The participation of technicians and office personnel in the strikes, not just in aviation but in many industries, was one of the most startling aspects of the "social explosion" since these employees lacked a trade union tradition and were usually loath to jeopardize their chances for advancement by organizing collectively to bargain with their employers.[84] Though a few technicians, like Lucien Llabre in Toulouse, had long identified with workers and even served in union locals, most white-collar employees had clung to the professional status their employers wanted them to claim. Yet however distanced these employees may have felt from industrial workers, in aircraft manufacturing they could not remain immune to some of the same frustrations and hopes that had led the latter to strike. They, too, were subject to layoffs amid the ups and downs of the aircraft business; they, too, suffered the indignities of life in an autocratic factory. The same esprit de corps that made skilled workers in aircraft manufacturing especially prone to defend their autonomy on the job could, under the right circumstances, inspire engineers and draftsmen to assert themselves collectively in the interests of professional pride. In aviation, moreover, technicians, especially draftsmen, were sufficiently numerous to make the logic of collective action compelling. It probably helped, as well, for technicians to rub shoulders with skilled metalworkers in prototype shops and test laboratories, in the process establishing personal channels of communication across the occupational divide. In addition, the ideological climate of 1936 was conducive to cooperation. The Popular Front, after all, embraced the notion of an alliance between the working and middle classes and called attention to the burdens middle-class citizens had had to bear under the deflationary policies of the center-right. The political and economic program of the left, not least its antifascism, found supporters in precisely the social groups to which technicians and office personnel belonged. Under these conditions it is not surprising that when factory occupations forced technicians and office personnel to take a stand, a number of them opted to join the strikers.

Once again the aircraft industry was in the avant-garde, for if technicians and cadres joined the strike movement in many other industries, it

was in aviation that separate unions for technicians and administrative personnel first emerged. The Matignon Accord provided impetus. By endorsing the principle of collective bargaining as a universal right, Matignon gave white-collar workers an incentive to create bargaining organizations of their own. In the midst of the strike movement aircraft technicians founded the Union Syndicale des Techniciens de l'Aviation (USTA), which quickly acquired three thousand members. Though the organization was not in a position yet to win a collective contract, it set a precedent for technicians in other industries, and by the fall of 1936 a new Fédération des Techniciens had emerged within the CGT. The USTA, too, made impressive strides. By August it issued the first monthly number of its newspaper for aircraft technicians in the CGT, Les Ailes syndicalistes, which proclaimed precisely what employers most feared about trade unionism spreading into the white-collar work force—that "technicians and workers, by forming an indivisible bloc, constitute an unequaled instrument for struggling against employer egoism and for the legitimate demand of employees."[85] Under the leadership of Raymond Thomas, the USTA not only provided thousands of technicians a way to affiliate with the CGT; it also served as a distinctively radical, anticapitalist voice in the white-collar ranks of the industry.

At the same time, however, a second white-collar organization emerged in aviation with a different bent. Naturally enough, employers throughout French industry had been shocked by the willingness of foremen, technicians, engineers, and administrative personnel to join the strike movement. In response a number of industrialists, first in aviation and then in most other major branches of industry, set out to co-opt their employees into alternative organizations independent of the CGT. This proved to be a shrewd tactic since many white-collar employees, although eager to engage in collective bargaining, were reluctant to join a CGT union clearly associated with working-class radicalism. Accordingly, on 22 June a group of administrative personnel, with active support from employers, founded the Syndicat des Cadres de l'Industrie Aéronautique (SCIA), and by the following December this new union had signed a collective contract with employers. From the beginning, then, white-collar unionism in aviation took two forms—the "yellow" unionism of the SCIA and the more radical unionism of the USTA within the CGT—a division that would continue to hamper the CGT's effort to build an alliance between technicians and blue-collar workers. Even so, June '36 was a turning point in the effort to bridge this occupational chasm in the industry.[86]

The strike movement had its greatest impact on the industry by inspiring workers to change the way they viewed themselves. As Pierre Monatte remarked, the French working class "regained confidence in itself"

during June.[87] Particularly in aviation workers built on the modest gains they had made since early 1934 to become an autonomous force in their own right with which employers and state officials would have to contend. However instrumental CGT militants proved to be in coordinating the strikes, rank-and-file workers were pivotal in making the strike movement a success. It was they who pushed their representatives to refuse compromises in negotiations; it was they who broke the grip of fear and paternalism employers had used to keep wages low and shop floors calm. Besides tangible gains, such as wage hikes, paid vacations, and the forty-hour week, employees won something deeper—the confidence to challenge the boss. What made June '36 a profound moment for workers was that by securing their rights to have trade unions, collective bargaining, and shop floor representation, employees broke through the ramparts of the autocratic factory. As Léon Blum said later, "The divine right of employers is dead."[88] By asserting themselves, aircraft employees suddenly introduced a new element of uncertainty into their industry—the possibility that workers, technicians, or office personnel might demand a say in decisions that would have to be made to wrest the industry from a structural crisis now years in the making.

Still, it remained to be seen whether aircraft workers would find ways to institutionalize the capacity for collective action that had sprung up so rapidly in the hothouse atmosphere of a national strike movement. It was one thing to triumph during the largest strike wave of the Third Republic; it was another to make an enduring commitment to the CGT once employers recovered their wind. Likewise, if aircraft workers by the thousands, and metalworkers by the tens of thousands, participated eagerly in the rituals of the strike movement—rallies, meetings, sentry duty, supply platoons, and the impressive marches that followed plant evacuations at the end of the strike—what would they do when the humdrum returned or when it came time to stick together against heavier odds? At the end of June, of course, no one could know. The fate of the Blum government was still a mystery. It was also unclear how far aircraft workers and trade union militants would go to try to change the structure of authority in the workplace. By revolutionary standards the achievements of June '36 were tame. The Communist Party, moreover, offered no real analysis of how the moderate objectives of the Popular Front might eventually connect to a revolutionary strategy.[89] Ironically, by winning moderate, practical concessions, the strikers of June '36 did more to undermine employer authority than had fifteen years of revolutionary agitation by unitaire militants. By achieving the old reformist goals of trade unions rights, shop floor representation, and collective bargaining with the blessing of a Popular Front government, workers put basic issues of industrial authority in the forefront of public debate.

"What frightened the intelligent and far-seeing representatives of the middle classes most," Blum said, "was the very moderation of this movement. . . . The workers installed themselves beside their machines, . . . making the necessary arrangements for the care of the plant. They were there as guardians, that is to say, as caretakers, and also in a certain sense as co-owners."[90] In the summer of 1936 no one knew for sure where this search for new forms of shared authority in the workplace would lead, especially with people clamoring for the nationalization of war industries. June '36 was not just the culmination of events since 1934; it was also the beginning of a new period of political education for everyone in the industry.

Four—

Nationalization