The Outer Terrace

The isolation of the outer terrace relative to the other terraces of the hermitage, as well as its distance from them, shows clearly in Figure 43 (see also Figs. 12 and 13). Even the contour of this terrace is odd, making it the most awkward of the man-made terraces to photograph and to describe. There is no one spot or angle on the rock from which it can be viewed in its entirety; only an aerial view shows its contours (Figs. 48, 49).

[18] We are grateful to Des Lavelle and Paddy O'Leary for permitting us to use their photographs. After the disappearance of the slab in 1977, Des Lavelle searched for it not only in Christ's Saddle below but on the ocean floor, in sea diving expeditions.

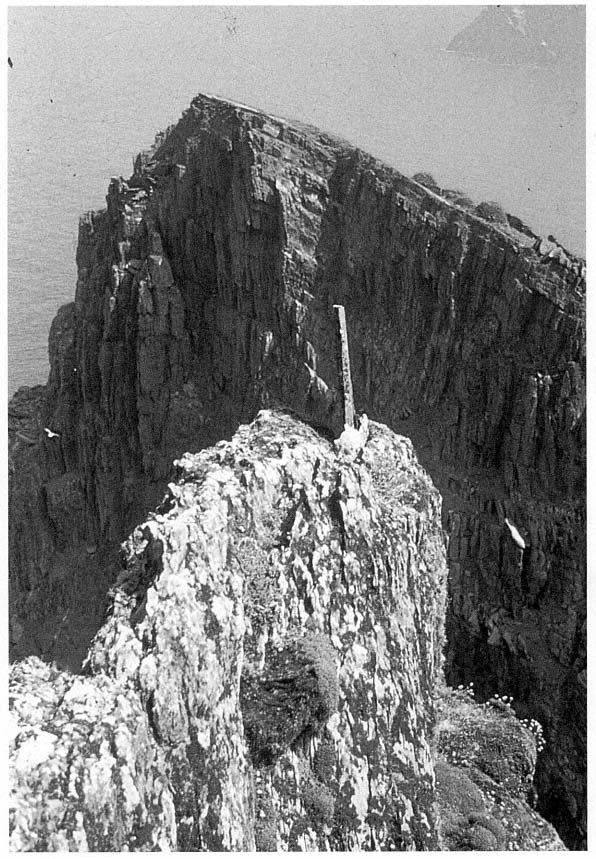

Fig. 47

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Photograph taken by Paddy O'Leary in 1977, showing the upright slab that

once stood at the easternmost end of the Spit.

Fig. 48

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Aerial view of the outer terrace taken from the northern side of the peak. A short stretch of the lighthouse road is visible

at upper left as well as some of the monastic stairways connecting this road with Christ's Saddle. Arrows (from left) mark the Spit; the rock mass below

which, on the other side of the peak, the oratory terrace is located (see Fig. 45); the garden terrace; (below) the outer terrace; and the Needle's Eye.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

Fig. 49

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Another aerial view of the outer terrace. The wall that frames it faces south at the top and

north at the bottom.

Photograph by Con Brogan. Courtesy Office of Public Works.

Essentially this area that we refer to as a terrace is structurally dissimilar to the others on the South Peak, for the masonry remains here consist of only a seventeen-meter-long wall along the perimeter. Nor are there signs that a single unified platform supported by retaining walls was ever intended. The construction of such a level terrace would be nearly impossible, for the topography consists of three natural stepped ledges whose elevations differ by as much as four meters. The terrain is irregular and steep, containing only a few square meters of level ground; moreover, there is no defining boundary on the northern and eastern sides.

The terrace is not mentioned in the accounts of earlier explorers, except for a casual remark of Lord Dunraven's: "There are also curious portions of an ancient wall on certain projections of rock near the Spit" (see p. 18). Liam de Paor also noted "some faint and somewhat doubtful traces of construction at one or two points along the way" (see p. 18). We believe that these remarks refer either to the small rounded section of wall visible on the climb

to the traverse below the summit (see Fig. 44) or to a larger section of wall visible from the summit itself (Fig. 50; the wall begins at about the level of the traverse and is lost to sight at the rounded section). These two small sections are all that can be seen of the outer terrace without climbing down to it.

The constant powerful winds blowing across the exposed terrain of the area below the summit make access to the outer terrace treacherous. No path exists, so one must climb gingerly down rough, sharp-edged ridges to reach the point where the masonry wall begins. Here one walks down along the top of the wall, perhaps planned at this point as a walkway, to reach a rock outcropping on which a few footholds have been carved. The footholds lead to level ground just where the wall turns a corner, where originally we believed a dry-stone beehive cell was located.

The first reaction is to gasp at the daring construction, to marvel at the stunning Atlantic beauty of the site, and to wonder, Why? Why was this ever built, this wall hanging on the edge of space? The first hermit who left

Fig. 50

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Part of the difficult path to the corner of the outer terrace. The corner lies at the outer

edge of a projecting spur of rock on the southwestern side of the South Peak some six meters below the summit.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

the monastery was going in one direction only—up, closer to God through a life of complete isolation on the island's highest point. Yet to inhabit this desolate area without shelter from winter storms was impossible. Could the outer terrace have been the location of the hermit's living quarters? Our first response to this question was an intuitive no. How could anyone survive on this storm- and rain-lashed ledge, where a freakish gust of wind might cause a loss of footing and a fatal fall? Because we could find no traces of a shelter on the lower man-made terraces on the peak, however, the question persisted. If the outer terrace were not the site of the hermit's dwelling, what was the purpose of its bizarre and extensive masonry? The construction of the wall, carefully built of medium-sized building stones with good internal and external faces, required intensive labor in an inhospitable, barely accessible area. What imperturbable man (or men) would carry building materials over a considerable distance to set stone upon stone on ledges that leave no room for even a stumble? As one contemplates this construction, one wonders whether at some point devotional submissiveness might have shifted imperceptibly into devotional hubris.

Although we know that construction is itself unequivocal evidence that the terrace was important, even as we continued our explorations we were unable to resolve our questions about the use of this site. On the most prominent part of the outer terrace, the corner, a curved and apparently corbeled wall looks like the surviving portion of a cell (Fig. 51). Further investigation showed, however, that instead of curving inward to form a small cell, the walls spread outward to follow topographical contours. Moreover, when the stones that had fallen into the interior were removed, what had looked like corbeling was revealed to be only a few courses high; the courses had been constructed so that the projecting rock became part of the wall, which elsewhere has a vertical face. Therefore it is not possible that a corbeled cell was constructed here, even though this may well have been the location of some sort of shelter.

Fig. 51

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Outer terrace. A detail of the corner, clearly revealing

what looks like corbeled stonework.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

This corner offers the best place on the outer terrace to construct an effective protection from the wind and weather, particularly because the ground level is one meter below that of the surrounding terrain. The argument for the presence of a shelter was strengthened by the discovery of a few pieces of rough flagging at the base of the corner. Had the entire area been flagged, there would have been a space just large enough for a recumbent hermit. Although final judgment awaits the clearing away of all the fallen rock, it can nevertheless be stated that an exceptionally minimal sheltered area probably existed here.

At the corner, the external height of the wall is now 2.5 meters, the internal height 1.07 meters, and the width of the wall from .6 to .8 meter at its present level. It is extraordinary that as one looks at the masonry from above, one is unaware that this semicircle of stones forms the top of a wall. Originally this wall was higher, possibly three to four meters high if it connected with the masonry above as indicated by the dotted line on Figure 52.

Fig. 52

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Remains of the walls that form the southeastern boundary of the outer terrace.

Photograph by Walter Horn. Dotted line indicates the possible height of the original masonry.

The lowest, northwestern, section of this terrace is even more puzzling than the corner. Here the wall curves, following an irrational downward course to a level 3.8 meters below the corner. Some seven meters lie between the highest point of the wall fragments on the south side of the outer terrace and those on the lowest, northwestern, side (Fig. 53). The external face of this wall is quite high in two places, about 3.2 meters. The original height of this wall and the function of the area it enclosed remain a mystery. The downward-curving wall is too far below the corner to have protected it from the wind. For this purpose, an inward-curving wall at a higher level, even at the level of the second ledge, would have been more effective. Perhaps the lower walls provided some shelter for a prayer station, however, for a small hand-sized cross, roughly shaped, was found in this area (Figs. 54 and 55).

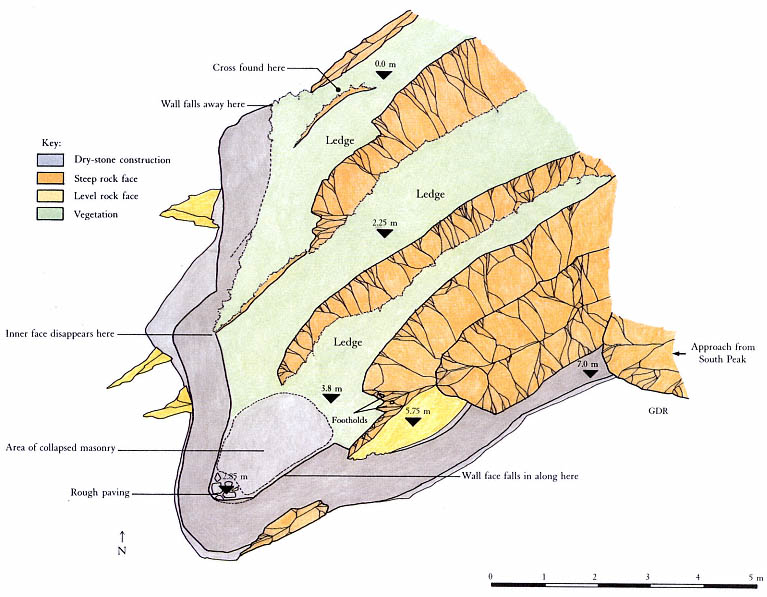

Fig. 53

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Plan of the outer terrace by Grellan Rourke, based on the plane-table survey of 1986.

Fig. 54

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Conjectural plan of the outer terrace by Grellan Rourke, showing where the hermit

might have had a shelter under a corbeled roof.

Fig. 55

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Cross found on the northwestern

side of the outer terrace, on its lowest level.

Drawing by Grellan Rourke.

Even as we speculated about the possibility that a minimal dwelling had been constructed on the outer terrace, we faced an additional question: Could anyone have endured there during severe storms? Even on sunny, warm days the South Peak winds are strong, sometimes dangerous, and this terrace is the one most exposed to wind.

Ocean winds normally sweep horizontally over the surface of the water. When their passage is blocked by the flank of an island such as Skellig Michael, with peaks rising to a considerable height, their force changes from horizontal to vertical. The resulting wind, sweeping upward, does not cease immediately on reaching the highest points of the island but pushes beyond, curving gradually back into its horizontal course under the pressure of the wind that surrounds and follows it. The resulting condition is referred to as a leeward vortex, a comparatively calm zone suspended in turbulent winds. These wind forces are largely responsible for the warmer, calmer microclimate that exists at the location of the monastery.[19]

The effects of the monastery's microclimate were dramatically demonstrated to us when we visited Skellig Michael early in the spring of 1972. The crossing was rough, and all of us were thoroughly chilled, despite our heavy layers of sweaters and our knitted caps. As we landed, the skipper, Dermot Walsh, advised us to leave all heavy clothing below because an entirely different, warmer, climate existed up at the monastery. Although in our chilled state we were reluctant to shed our warm gear, we found the skipper's advice borne out when we reached the summit and were able to discard our heavy clothing.

Could similar illogical climatic variations be expected on the windlashed top of the South Peak? The two peaks differ significantly in their conformation and size. The monastery was built at the southern end of an extensive inclined rock plateau that rises some fifteen meters behind it, ensuring the continued upward sweep of the north and west winds past the monastery. The South Peak has a much smaller mass and rises to a greater height than the monastic peak. As it rises, it loses much of its bulk, so that at the level of the outer terrace there is no protection from the wind. A microclimate here similar to that of the monastery summit is impossible. Walls to deflect the wind would be critical for protection on this terrace.[20]

The rock formation and wall provide good protection from southern and southeastern winds. The wall on the northwestern side provides partial protection from winds. No such barrier, however, exists on the northern or northeastern sides of the terrace. There a hermit would have been exposed to the full force of the worst storms coming from those directions.

These barriers interacting could provide only marginal protection on this desolate site in good weather and would be completely inadequate in winter or during a major storm. No one could survive such conditions without better shelter. Moreover, during rainstorms, torrents of water cascading off the ledges guarantee that anyone on the outer terrace will be thoroughly

[19] The climate on the peak where the monastery is located is also determined by a combination of other factors such as solar aspect and the albedo and heat retention capacity of the native bedrock (written communication from R. Berger, professor of geography and chairman, Department of Archaeology, University of California at Los Angeles).

[20] It is possible that the better climate existing in the Early Christian period, at its peak in the tenth and twelfth centuries, may have ameliorated conditions somewhat. It is almost impossible, however, to assess the main climatic difference—that there were fewer storms of lessened intensity—for a hermit living on the South Peak.

drenched. Winds of near-hurricane force make movement to and from the terraces extremely hazardous, if not impossible. A hermit may have spent many a stormy night praying in the oratory, on the best-protected terrace on the South Peak. Even under the best conditions, however, he would frequently have been cold, wet, and at risk of serious injury or death. But the goal of an ascetic was not comfort; the Cambray Homily reminds us:

This is our denial of ourselves, if we do not indulge our desires and if we abjure our sins. This is our taking-up of our cross upon us, if we receive loss and martyrdom and suffering for Christ's sake.[21]

[21] "Ocuis numsechethse isée ar n-diltuth dúnn fanissin mani cometsam de ar tolaib ocuis ma fristossam de ar pecthib. issí ticsál ar cruche dúnn furnn ma arfóimam dammint ocus martri ocus coicsath ar Chriist" (Cambray Homily in Thesaurus Paleohibernicus , ed. and trans. Stokes and Strachan [1901], 1975, 2:245).