Chapter One

The Name of the Nautanki

First Meeting

Once in a land far, far away, there lived a princess of peerless beauty. She dwelt cloistered in an impenetrable palace, surrounded by dense groves and watched over night and day. Distant and inaccessible though she was, her name had reached all corners of the country. Here was a damsel whose delicacy put even the fairies to shame. The radiant glow of her body made the moon's luster pale. Her eyes were like a doe's; she had the voice of a cuckoo. When she laughed, jasmine blossoms fell. In the prime of her youth, she maddened men with her lotus-like breasts and the three folds at her waist. Whenever she set foot outside, she was as if borne aloft on the gusts of wind, like a houri of paradise. Such was her supreme ethereality that her weight could be measured only against a portion of flowers.[1]

This princess was known in many different regions of India. She appeared under a series of names, each incorporating the word phul , meaning "flower." In Rajasthani folklore, she was called Phulan De Rani, and she was pursued by a prince who was the youngest of seven sons.[2] In the pan-Indian tale of two brothers named either Sit and Bas-ant or Rup and Basant, princess Phulvanti weighed only one flower.[3] In Sind and Gujarat, she was known as Phulpancha (five flowers) because the fifth flower caused the balance beam to tip. Here too she was associated with a two-brother team, Phul Singh and Rup Singh, the younger

of whom was her suitor.[4] In the Goanese account, her name was Panchphula Rani, as it was in one North Indian version.[5] The Punjabi tale styled her Badshahzadi Phuli or Phulazadi, "Princess Blossom" as translated by colonial collectors.[6]

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, when most of these tales were recorded, a drama called Princess Nautanki (Nautanki shahzadi ) was also being performed. It employed a music-laden style popular in rural Punjab and Uttar Pradesh.[7] Nautanki was Panchphula literally weighed in a different coin. Nau means "nine" and tank , a measure of silver currency equivalent to approximately four grams. Thus Nautanki: a woman whose weight was only 36 grams. Nautanki was the princess of Multan, flower-light, fairylike, whose fame had traveled far and wide. She was the beloved of the Punjabi lad Phul Singh, younger brother of Bhup Singh. Her story is still being told.

What is it like, this roving theatre? What is its name, do you know? This is Nautanki. That's right, Nautanki! The chief attraction of village fairs in Uttar Pradesh. Several days before the fair starts, the tents; and trappings arrive on a truck and are set up at a fixed spot. A large tent is stretched out to form a hall. At its head, a good-sized stage is erected and adorned with curtains. All the arrangements are made for the lighting. In front of the stage, places are fixed for the audience to sit. A big gate is put up outside, and a signboard attached to it with the name of the Nautanki. As soon as the bustle of the fair gets underway, the main performers arrive on the scene. Then at a fixed time an announcement is made and the Nautanki commences. The same individuals you watched putting Up the tents and curtains now appear before you on stage, acting out roles and singing and dancing.[8]

NAVBHARAT TIMES INTERVIEWER: Your name has become almost a synonym for Nautanki nowadays. When and how did you become associated with it?

GULAB BAI, FAMOUS NAUTANKI ACTRESS OF KANPUR: This is the result of my fifty-five years of self-sacrifice. My father was a poor farmer. He was the one who had me join Trimohan Lal's company in 1929. I was only eleven years old at the time. With Trimohanji's guidance, I worked in the company for roughly twenty years. In the beginning, I got about 50 rupees a month, which later rose to 2,000 rupees.

NAVBHARAT TIMES: After working in Trimohan's company for so many years, why did you decide to leave and form your own separate company? And how did you become successful at operating it?

GULAB BAI: That decision grew out of an unfortunate incident. My sister fell off a balcony and was seriously injured. I asked Trimohanji for money for her medical treatment. He put me off with "Come back tomorrow." I told him any number of times that her condition was deteriorating, but he wouldn't listen to me. So that was when I left the company. Later I got together with my sisters Pan Kunwari, Nilam, Suraiyya, and Chanchala Kumari, and we formed a separate company. We organized the costumes and props and so on and started playing for wedding parties. The audiences praised us. In that way, we started up, with our own dedication and others' blessings.

NAVBHARAT TIMES: Up until now how many performances have you given?

GULAB BAI: It's difficult to tell exactly how many performances there have been. But by 1942 I had performed approximately twenty thousand times.[9]

MALIKA BEGAM, NAUTANKI ACTRESS OF LUCKNOW: Previously, big officers used to call for us every day. They'd summon the Nautanki company managers and tell them to make the necessary arrangements. Then all the big officials, their wives, all the best gentry, all kinds of people would come. . .. The public was extremely fond of Nautanki. Whenever a program was over and we were leaving by bus or train, all the students, leaders, and so on brought bouquets and bade us farewell. Such respect, how can I tell you? . . . When we were on stage, there could be a dead body lying at home, but when we went on stage, we thought that if we were playing Laila, we were Laila; if we were playing Shirin, we were Shirin. We forgot our everyday reality, whatever we were.

KATHRYN HANSEN: How many people were in your company?

MALIKA BEGAM: At that time, including labor, there were eighty. It depended on the scale of the company. If it was small, then fifteen, twenty, twenty-five men; if large, then eighty or a hundred, including labor. There were four managers in each of the big companies.

KATHRYN HANSEN: How much did you make back then?

MALIKA BEGAM: Sometimes 2,500 rupees a month, sometimes 2,000.[10]

The Hindi author Phanishwarnath Renu describes the encounter of a cartman and a Nautanki actress in his short story "The Third Vow."

Everybody had heard of Hirabai, the actress who played Laila in the Mathura Mohan Nautanki Company. But Hiraman was quite extraordinary. He was a cartman who'd been carrying loads to fairs for years, yet he'd never seen a theatre show or motion picture. Nor had he heard the name of Laila or Hirabai, let alone seen her. |

So he was a little apprehensive when he met his first "company woman" at midnight, all dressed in black. Her manager haggled with him over her fare, then helped her into Hiraman's cart, motioning for him to start, and vanished into the dark. |

Hiraman was dumbfounded. How could anyone drive a cart like this? For one thing, he had a tickle down his spine, and for another, a jasmine was blooming in his cart. Only God knew what was written in his fate this time! |

As he turned his cart to the east, a ray of moonlight pierced the canopied enclosure. A firefly sparkled on his passenger's nose. What if she were a witch or a demon? |

Hiraman's passenger shifted her position. The moonlight fell full on her face, and Hiraman stifled a cry, "My God! She's a fairy!" |

The fairy opened her eyes.[11] |

Alternative Etymologies

To educated Indian ears, the word nautanki sounds a bit uncouth, with its hard consonants and nasal twang. Hindi dictionaries do not include the term before 1951. It occurs in neither Thompson's Dictionary in Hindee and English (1862) nor Platts's Dictionary of Urdu, Classical Hindi, and English (1884). Of the Hindi-English dictionaries currently in wide use, Chaturvedi and Tiwari's Practical Hindi-English Dictionary contains no entry, and the Minakshi hindi-angrezi kosh says simply "folk-dance, village-drama." Nor does the unabridged Hindi shabd sagar (1968) mention Nautanki in its ten volumes. Ramchandra Varma's Pramanik hindi kosh (second edition, 1951) appears to contain the first dictionary definition: "a type of renowned drama occurring in the Braj region in which they act and sing chaubolas (quatrains) to the accompaniment of the nagara (kettledrum)." The most detailed entry is in the fifth edition of the Manak hindi kosh (1964): "A type of folk-drama performed among the common people, whose plot is generally romantic or martial, and whose dialogues are usually in question-answer form in verse. It contains a predominance of music and chaubolas are sung in a particular manner accompanied by the dukkar (paired drums) or nagara ."

What explains the late occurrence of these definitions? And why does

the lexical silence persist? Sampling the dictionaries would lead us to believe that this folk art is obscure and insignificant. But dictionaries are slanted mirrors of language and society, reflecting the linguistic tapestries constructed by social, political, and economic forces at different moments of history. We might wonder if a censorious intent is at work, an effort to expunge Nautanki from the authorized indexes of the language. We begin to suspect from its omission that Nautanki may not rank with the prestigious, officially approved performance genres of modern India. Why then this attempt to exclude Nautanki from the canons of acceptable speech?

Part of the reason may be the uncertainty of its etymology. Most of the generic labels for folk theatre in North India are derived from words meaning "stage, play, show, processional theatre," for example, the Manch of Madhya Pradesh (from Sanskrit mancakam , "stage"), the Ram and Ras Lilas of Uttar Pradesh (Sanskrit lila , "sport, play"), Maharashtra's Tamasha (Arabic tamasha , "entertainment, spectacle"), Bengal's Jatra (Sanskrit yatra , "procession, pilgrimage"). In the parallel etymology conjured by Hindi scholars, nautanki has been traced to nataka , the Sanskrit high drama, via a hypothetical term nataki . The argument is inconclusive in the absence of references to nataki the dramatic literature. Taking another approach, Hindi novelist Amritlal Nagar explains the term as the theoretical admission price, nau tanka , nine silver coins, or as the fee paid by a patron for sponsoring a performance, nau taka , nine rupees. Others believe the word refers to a distinctive music and drumming style, nay tankar , "new sound."[12]

Beyond these speculations, folklore preserves the story of Nautanki, the beautiful princess of Multan. The dramatized romance of Phul Singh and Nautanki (although it may be older) first appears in published form as Khushi Ram's Sangit rani nautanki ka (The musical drama of Queen Nautanki) in 1882 (fig. 1). R. C. Temple lists "Rani Nautanki and the Panjabi Lad" in his index of legends collected from the Punjab in the 1880s. In the early 1900s, folk-drama poets from the Hathras area, Govind Chaman, Muralidhar, and the famed Chiranjilal and Natharam team, composed their much published versions of the story; they had many imitators (fig. 2). The popularity of the tale grew with repeated performances, as the folk theatre moved out from the Punjab region and Haryana into Uttar Pradesh and Bihar in the twentieth century.[13]

The traditions of the Nautanki theatre, moreover, include a metastory. The name of the princess Nautanki became so famous that it came to signify the theatre genre itself.[14] Such semantic extension is not

Fig. 1.

Title page of Sangit rani nautanki ka by Khushi Ram (Banaras, 1882).

By permission of the British Library.

Fig. 2.

Title page of Sangit nautanki featuring portrait of the author,

Chiranjilal (Mathura, 1922). By permission of the British Library.

unknown to classificatory practices in North India. The name of a protagonist may designate a story, as well as the poetic meter used to tell that story, the musical motif associated with the meter, and finally the performance genre as a whole. For example, Alha is the name of a twelfth-century Rajput hero whose exploits were set down in the Alha khand of Jagnaik. Alha refers to the martial saga, which engendered a specific performance style called Alha, sung in the alha meter, to a tune recognized by listeners as alha , practiced by alha ganevale (Alha-singers)—which now includes other topics along with the original story of Alha.[15] Another example is Dhola, hero of the medieval Rajasthani epic Dhola maru. Dhola is also the classifier of a North Indian ballad form.[16] So too "Nautanki" names the beautiful princess, her well-known tale, and the unique theatrical style in which her story is performed. In popular usage, nautanki also refers to an item in the performance repertoire, as in the question, "Which nautanki did you see?"[17]

Having clarified the issue of etymology, let us return to the question of Nautanki's absence from the lexicons. A clue may be discovered in the unusual association of a folklore genre with a female character. Whereas the Alha and Dhola epics are named for male warriors, this art draws its title from a princess. The fetching Nautanki of legend may be intent on conquest, but her territory is the heart, not the battlefield. Does this make her theatre less noble than the epics of the heroes? What is implied when a theatrical tradition is identified with a woman, a supremely desirable woman? The nomenclature linking this folk theatre with the female gender may be the most singular indicator of its nature. It suggests the sociolinguistic and cultural veils that have cloaked Nautanki in mystery thus far.

The Journey

Many men had tried to attain the enchanting princess Nautanki but none had succeeded. One day the Punjabi youth Phul Singh returned home from a hunt. He impatiently ordered his elder brother's wife to fetch him cold water, get his food ready, prepare smoking materials, and make up his bed. She rebuked him sharply, telling him to go win the hand of Nautanki if he wanted a woman to serve his every need. Affronted, Phul Singh vowed not to return home again unless Nautanki came with him. Alarmed at his rash words, his sister-in-law retracted her dare. His father begged him not to leave home, and his mother offered to marry him to some other bride. But Phul Singh was adamant.

His heart now inflamed by the passion of pure love, he said farewell to family, friends, wealth, and country, and set off on his quest. He journeyed for many days on horseback, until at last he reached the fort of Multan. He entered the city and soon came to the garden of the princess Nautanki.

As Phul Singh entered Nautanki's private garden, he was accosted by a malin , an old woman gardener, who warned him away. He begged to stay overnight, winning her consent finally with a gift of money. Phul Singh helped the malin weave a special garland to present to Nautanki, affixing a gem of his own. When the princess saw it, her left eye throbbed, her breast quivered, and she sensed her future husband was near. But she said nothing and demanded that the malin produce the maker of the unusual wreath. Phul Singh directed the malin to disguise him as her newlywed daughter-in-law and lead him into court. Decorated in full feminine array, Phul Singh at last beheld his beloved, but he could not speak his heart for fear of revealing himself. Nautanki was enchanted by the lovely young girl she saw before her. Overcome with desire, she decorated her bed with flowers and invited the bride to come lie with her.

DHARMYUG INTERVIEWER: Sometimes you're here, sometimes you're there how do you like all this traveling about?

MASTER SURKHI, A NAUTANKI ACTOR AND TROUPE MANAGER: Don't ask, mister, it's a gypsy's life. You can imagine what it's like: loading all the tents onto the truck, traveling, digging a well at a new place, drinking the water. Deciding on the site, then putting up the tents. But what can I do? I have no choice. The whole burden falls on my shoulders now. When I worked as a laborer in Babu Khan's company, I never worried about anything. In those days, I put on airs and made demands. Now I have to put up with all the airs of my own performers. Always I'm the one responsible for their welfare. It's a huge botheration, sir, running this company. On top of that, I have to deal with the intimidation, the extortion from the police, the bosses, and the thugs in the cities. Get them free passes to the shows. And the heaviest tax falls on Nautanki companies. It's more than they charge the circus or drama companies. Sometimes we get caught in a storm and the whole kit and caboodle gets wrecked. One night at the Rampur Exhibition there was a terrific rainstorm—don't even ask! All the tents were ripped up, everything a shambles. The hall totally flooded with water. There are a thousand hassles, but how can we go on crying about them?

The tented hall overflowed with people. Tube lights and naked bulbs lit up the sea of faces. Huge painted curtains covered the stage, while below a musician stood at an old-fashioned foot-pumped harmonium. To one side of the stage sat the aged

nagara player, sticks poised to beat on his kettledrums. Beside him another drummer braced his dholak . With a flourish, the percussionists began the overture, regaling the audience with a volley of drum rolls. Then the joker entered, an odd toothy character in greasepaint and motley costume. Screwing up his face, he announced the arrival of his "wife."

The first dancer came onto the stage, a fleshy young lady with a huge bun of hair, arching painted eyebrows, and excessively red cheeks. Her sari was slung below the navel. She fluttered her eyelids at the audience and, pouting, saluted the musicians and gestured for them to start. As the song began she danced, revealing every limb and contour of her body. The audience hooted and shouted, and dug deep into their pockets for rupee notes that were passed to a boy on stage. With the note came the name of the donor. The dance stopped, and the boy announced the donor's name over the microphone. The dancer smiled and set her body in a suggestive pose. "I wish to thank that kind gentleman, Mr.———, and my darling public," and she thrust her hips lewdly and continued with her dancing.

MALIKA BEGAM: Now those big people don't like to come. Why? Because the wrong type of women have come into this, women who are not artistes. They learn a few songs—I mean, the prostitutes. Their profession has been banned so they've entered this one. Imagine, when these women come amidst the public, sit there, grab their clothes, do this and that and somehow earn a tip, then theatre is a thing quite distant. If they give a push, thrust their bodies, and beg for a tip, it's no matter of shame for them. But for me it is the same as dying. At the most, I can say thank you like this [gestures with namaste ], no more. If it's a special occasion, some big leader, someone to pay respects to, that's all I can do. I can't do all that just to get a tip. These people have fouled the atmosphere.

Forbesganj was Hiraman's second home. Who knows how many times he'd come to Forbesganj carrying loads to the fair. But carrying a woman? Yes, one time he had when his sister-in-law came to live with her husband. They put a canvas enclosure around the cart, just as Hiraman was doing now. |

The fair was to open tomorrow. Already a huge crowd, and the camps were jammed with tents. First thing in the morning Hirabai would go join the Rauta Nautanki Company. But tonight she stayed in Hiraman's cart, in Hiraman's home. |

Next day, Hirarnan and his two companions entered the eightanna section. This was their first look inside a theatre tent. The section with the benches and chairs was up front. On the stage hung a |

curtain with a picture of Lord Ram going to the forest. Palatdas recognized it and joined his hands to salute the painted figures of Ram, princess Sita, and brother Lakshman. "Hail! Hail!" he uttered as his eyes filled with tears. |

Dhan-dhan-dhan-dharam ! rolled the drums. The curtain rose. Hirabai immediately entered the stage. The tent was packed. Hiraman's jaw dropped. Lalmohar laughed at every line of Hirabai's song, for no good reason. |

"Her dancing is incredible!" |

"What a voice!" |

"You know, this man says Hirabai never touches tobacco or betel." |

"He's right. She's a well-bred whore." |

Renu's Actress

The word Nautanki first entered my vocabulary when I read Renu's Hindi short story, "The Third Vow." Set in his home district of Purnea in Bihar, the story follows a rustic cart driver as he hauls an unusual load—a Nautanki actress—to a rural fair. During their journey, a tender and sheltered friendship develops between the illiterate laborer Hiraman and the urbane, glamorous Hirabai. The friendship somehow survives the disorienting experience of the fair, where Hiraman attempts to protect himself and Hirabai from the common view that the Nautanki theatre is disreputable and its actresses dissolute.

Renu writes into his text the sensory dimensions of experience, the sounds and smells, the feel of the countryside. The lurch of the cart into the ditch, the fragrance of night jasmine, the crescendo of kettledrums, the tingle of fear and pleasure down the spine: these details carry the reader into a palpable realm where emotion and sensation intermingle. Meanwhile, the story creates a rich contextualization of Nautanki, evoking the theatrical experience in rural India, and telling us much about the mythic meanings of folk theatre for its audience.

Renu places Nautanki in the premodern landscape of India's northern plains. In this world of villages, cartmen, loads, and country fairs, transport by rail or truck is yet to come. Goods—be they legal or contraband, tied down or unwieldy, inanimate or dangerously alive (as narrated in the tales of Hiraman's cloth smuggling, bamboo hauling, and tiger transporting, all activities he has now foresworn)—move on creakyaxled cart beds drawn by recalcitrant bullocks. The carts wind down dusty tracks, or stray off to less-worn paths, crossing dry riverbeds and

pausing beneath the occasional shade tree for respite from the sun. The sites of fairs and markets are the nodes in this network of tracks, bringing together drivers and their customers, and offering opportunities for camaraderie, entertainment, and relaxation.

This is a psychic world of limited compass for its inhabitants. Its boundaries are marked in tens of miles rather than hundreds. Hiraman's map includes his village, his "second home" of Forbesganj, and of course, the road. Names like Kanpur and Nagpur, large cities to the west and south, are well known to Hirabai, worldly woman that she is, but to Hiraman, with his childlike literalism, they signify only "Ear City" (kan pur ) and "Nose City" (nak pur ).

Theatre by its nature is concerned with illusion, disguise, and even duplicity; in many societies it evokes distrust and hostility.[18] But in rural India, the suspicious. enterprise of theatre is made stranger still by differences in power, culture, and status that separate city and village. The arrival of any citydweller in the village arouses a fear of exploitation and degradation; suddenly the villager's knowledge and authority appear deficient by comparison. Nonetheless, contact with certain categories of outsiders—traveling preachers, itinerant entertainers, or in the new age, campaigning politicos—offers a periodic means for the village to obtain both amusement and information. Such visitations are temporary and may not impose a challenge on the existing pattern of life, yet the outsider retains an aura of fascination and fear. The safest attitude seems one of deference.

It is natural then that the cart driver Hiraman should react with apprehension, even terror, when he first encounters an actress, Hirabai, late one night. He fears she might be a demoness or a witch: dangerous residues of repressed female rage, who return after a woman's death to torment her former oppressors. Instead, in the moonlight Hirabai's face reveals her to be a fairy (pari ), an equally unearthly but beneficent supernatural. Paris are the residents of heaven in Indo-Islamic mythology, counterparts to the apsaras of Hindu legend, and they appear in many late medieval narratives as well as in the drama. Ethereal, unweighable, borne on the breeze, the fairy is a paragon of beauty, the ideal form of the beloved.

As the story advances, Hiraman domesticates this otherworldly being—paradoxically, by deifying her. He interprets her kindness in conversing with him as a boon of the goddess, an act of grace. To Hiraman, it is as though one of the celestials is riding in his cart, a reference to the practice of publicly parading the temple idol in a cart during annual temple

festivals. The dedication and service that Hiraman offers to Hirabai—his protection of her inside the canopy, his ritualized offering of food and drink, and his constant attentions—are the appropriate gestures of a devotee toward the divine. All these behaviors are justified and symbolized through the appellation he gives her, "Hiradevi," Hira the goddess.

The status attached to god or goddess implies a hierarchy, the worshiper figuratively and literally placed beneath the deity. Yet in India, the relationship a worshiper enjoys with the divine is intense and volatile in affect. A widespread cultural metaphor likens the deity and the devotee to lovers in the most intimate emotional bond. Within this mode, opportunities exist for the worshiper to invert the hierarchy and "dominate" the chosen deity with demands, pleadings, and offerings. Hiraman's deification of Hirabai keeps her at a safe distance, but it also provides a known avenue of approach. His response illustrates the comfortable adulation heaped upon theatre artists and other celebrities by the rural audience. "Gods from another realm" is one way in which they can be appropriated and rendered manageable.

Against this cluster of admiring attitudes stands the complex of prohibitions and taboos associated with all secular entertainments, but especially dance, theatre, and film in India. Hiraman, an innocent, has never seen a theatre show or motion picture, largely because he fears his sister-in-law's disapproval. When he meets his fellow cartmen in Forbesganj, they make a pact that none will mention their Nautanki experience back in the village. The basis for their circumspection is guilt by association, for "company women" are reputed to be prostitutes. This widely held perception challenges Hiraman and torments him throughout his stay in Forbesganj, but he continues his protective behavior toward Hirabai, brawling with audience members who "insult" her and later suggesting she abandon acting and join the more respectable circus.

No specific information is presented in Renu's story about Hirabai's sexual life, and to the end the reader remains in the dark (as does Hiraman), unable to determine if Hirabai ought to be ranked as a goddess or a whore. This authorial withholding is one of the sources of bittersweet ambiguity in the story. Beyond the text, however, the selling of sexual favors is not essential to the definition of a stage actress as a prostitute, either in North India or in other societies. Gender roles in this agriculturally based patriarchal society are defined in spatial terms, with women occupying private inside spaces and men public outer ones.

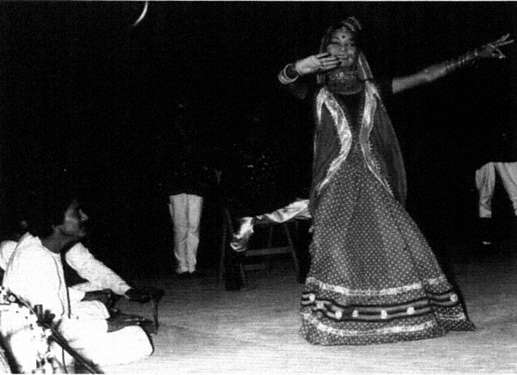

Fig. 3.

Dancing girl performing in Sultana daku . By permission of the Sangeet Natak Akademi.

Women are valued for their domestic labor and for their reproductivity, which must be controlled for the perpetuation of pure family and caste lines. Enclosure, whether effected by parda (the curtain or screen of a segregated household), by the canopy of a bullock cart, or by a veil or sari-end drawn over a woman's face, is conceived as necessary to preserve a woman's chastity and, by extension, her menfolk's honor. Since the social construction of gender places "good women" in seclusion, women who appear in public spaces (such as on stage) are defined as "bad," that is, prostitutes. Subjected to the gaze of many men, they belong not to one, like the loyal wife, but to all (fig. 3).

Clash and Conquest

Phul Singh, who was so close to the object of his desire, trembled with fear of discovery. He asked Nautanki why such a lovely princess as herself was as yet unmarried. She replied: | |

Listen, most excellent gardener girl, | |

I am weighed in flowers until now. | |

No man has proven worthy of me, | |

So I've remained single, in spite of my budding youth. | |

Seeing you, my friend, a wave surges in my heart. | |

Oh sweet, if only one of us could be changed into a man, | |

We could spend the whole night making merry in bed, | |

Happily embracing, giving and taking, | |

Drinking the cup of union | |

Phul Singh recommended she pray for a boon and, as Nautanki closed her eyes and prayed to her pir (saint), removed his disguise. All obstacles now eliminated, the two spent the night together. | |

In the morning, Nautanki was weighed in flowers as usual, but this time the scale tipped; she was heavier from her contact with a man. When the king, her father, discovered the insult to his honor, there was an uproar in the palace. He ordered Phul Singh to be arrested and brought before the kotval (chief of police). Nautanki tried to buy her lover's release by offering the kotval her necklace. But Phul Singh was sentenced to hang. The grieving lovers were parted, as Nautanki promised to meet Phul Singh once more. | |

GULAB BAI: There's one incident I'll never forget. It was when I was with Trimohan's company, during the period of the British Raj. Some antisocial elements had entered the hall and were sitting in the audience. The police were having a hard time controlling them. So the British kotval , one Mr. Handoo, declared that we were a threat to law and order, and he had us banished from the city.

"Where's the man who said that? How dare he call a company woman a whore?" Hiraman's voice rose above the crowd.. |

"What's it to you? Are you her pimp?" |

"Beat him up, the scoundrel!" |

Through the hullabaloo in the tent, Hiraman boomed out, "I'll throttle each and every one of you!" Lalmohar was assaulting people with his bullock whip. Palatdas sat on a man's chest pummeling him. |

The Nautanki manager rushed over with his Nepali watchman. The kotval rained blows on all and sundry. Meanwhile the manager had figured out the cause of the fracas. He explained to the kotval , "Now I understand, sir. All this trouble is the work of the Mathura Mohan Company. They're trying to disgrace our company by starting a brawl during the show. Please release these men, sir. They're Hirabai's bodyguards. The poor woman's life is in danger!" |

The kotval let Hiraman and his friends go, but their carter's whips were confiscated. The manager seated all three on chairs in the one-rupee section and told the watchman to go and bring them betel leaf by way of hospitality |

At the gallows two executioners, one wicked and one merciful, debate over Phul Singh's fate. Suddenly Nautanki storms the execution ground, dressed as a man and armed with sword and dagger. Phul Singh is content with this last glimpse of her, and he says goodbye to the world as the noose is placed about his neck. But Nautanki pulls out a cup of poison and prepares to commit suicide, vowing to die as Shirin died for Farhad and Laila for Majnun. As the executioners advance to pull the cord, she rushes with her dagger and drives them off. She then turns her sword on her father, demanding he pardon her lover at once. The king consents to the marriage and the two are wed on the spot. Phul Singh, his mission accomplished, returns forthwith to the Punjab with his new bride. The story ends with a blessing for the audience: "Thus may all lovers gain the fulfillment of their desires."

Hiraman turned his head when he heard Lalmohar's voice. "Hirabai's looking for you at the railway station. She's leaving," Lalmohar related breathlessly. Hiraman ran to the station. |

Hirabai was standing at the door to the women's waiting room, covered in a veil. Her hand contained the coin purse Hiraman had given her for safekeeping. "Thank God, we've met," she held out the purse. "I had given up hope. I won't be able to see you from now on. I'm leaving!" |

Hiraman took the purse and stood there, speechless. Hirabai became restless. "Hiraman, come here inside," she beckoned. "I'm going back to the Mathura Mohan Company. They're from my own region. You'll come to the fair at Banaili, won't you?" |

Hirabai climbed into the compartment. The train whistled and started to move. The pounding of Hiraman's heart subsided. Hirabai wiped her face with a magenta handkerchief and, waving it, indicated "Go now." |

The last car passed by. The platform was empty. All was empty. Hollow. Freight cars. The world had become empty. Hiraman returned to his cart. |

He couldn't bear to turn around and look under the empty canopy. Today too his back was tingling. Today too a jasmine bloomed in his cart. The beat of the nagara accompanied the fragment of a song. |

He looked in back—no gunnysacks, no bamboo, no passenger. Fairy ... goddess ... friend ... Hiradevi—none of these. Mute voices of vanished moments tried to speak. Hiraman's lips moved. Perhaps he was taking a third vow—no more company women. |

Gender and Genre in Nautanki shahzadi

Two journeys concluded: Phul Singh returns home with princess Nautanki, Hiraman leaves Hirabai behind. Beginnings sparked by impatience, greed, curiosity, desire. Breaks from family, ejection from home, travels on the open road. Middles strewn with obstacles, clashes, danger, and fear. Disguise and counterdisguise, wooing and counterwooing. Different endings. Phul Singh completes the quest, makes his conquest, lives to bestow his good fortune on the hearers of his tale as reward for their listening. Hiraman, reputation and purse intact, loses his heart and his innocence. His third vow—not a blessing but a warning, compressed confession of comic defeat.

Renu's account is a modern fairy tale, departing from traditional narratives in the ambiguity of its ending. The short story provides an excellent account of the connection between theatre and its rural audience. The mixture of fascination and fear focused on the exotic, prohibited category of womanhood represented in the Nautanki actress could not be more eloquently described. Nautanki shahzadi (Princess Nautanki) parallels Renu's tale, reproducing a structure of avoidance and attraction between the sexes analogous to the troubled relations between theatre and society. If nautanki became a byword for the theatre, as the metastory asserts, then the Nautanki shahzadi drama must have paradigmatic value for the genre as a whole. Its preoccupations, particularly its problematic construction of gender roles and sexuality, require attention if the meaning of this story to the theatre it names is to be understood.

At first glance, the romance of Phul Singh and princess Nautanki simply retells the age-old tale of a proud young man pursuing a distant and difficult love object. The tale's narrative syntax is familiar to both the folklore of South Asia and the larger Indo-European tradition. It begins with a rupture in family life (the quarrel between Phul Singh and his sister-in-law), the imposition of a task (winning Nautanki as bride), the hero's vow to fulfill the task, and his departure from home. The next stage consists of various obstacles (the journey, the garden, the palace) and strategies for overcoming them (magic objects, helpers, disguise), resulting in the hero's successful wooing of Nautanki. Then a second stage of difficulties ensues, when the hero is apprehended and punished for his amorous actions. After this section, the heroine emerges as the rescuer, creating a mirrorlike pattern of counterdisguise and counterwooing. The conclusion proceeds from her victory, the couple is reunited, and they return home to a restored order.[19]

This story, as narrated in the chaubolas of Chiranjilal and Natharam, Govind Chaman, and Muralidhar, early poets of the Hathras branch of Nautanki, acquires the Indo-Islamic coloration typical of the genre. Internal allusions link it to the body of tales and motifs common across the region, causing it to blend with other familiar stories in the hearer's mind. Characteristically, when Phul Singh declares his resolve to leave home and seek Nautanki as his wife, he calls his period of separation from family "forest dwelling" (banvas, ban khand ), terms used ordinarily to describe Ram's years of exile in the forest in the Ramayana . Phul Singh's departure is also repeatedly compared to the act of renunciation of a yogi or fakir (yogi and faqir , Hindu and Muslim ascetics respectively), especially as parents and friends try to dissuade him from venturing forth. In just the same way, Gopichand (and other kings) are warned against renouncing the world in the cycle of Gopichand-Bharathari. Phul Singh's well-wishers urge him to forsake the tragic path of love, citing the failure of famous couples to achieve union.[20] Laila and Majnun, Shirin and Farhad, Hir and Ranjha, all of whom are the subjects of other Nautanki plays, are held out as precautionary examples, while Phul Singh vows to strive unto death for his beloved, citing the evidence of love's power from the same set of stories. These allusions not only legitimize Phul Singh's venture and enhance his heroic status, they bring about an overlapping of tales and motifs traceable to Sanskritic and Islamic sources, illustrating the eclectic borrowings of popular culture.

An experienced reader of Indian literature will notice in Nautanki

shahzadi other elements common to classical and medieval tales. The formulaic scene of leavetaking, with effusive demonstrations of pathos and attachment offered by family and friends, suggests the departure of Ram in the Ramayana , although the Tamil genre of farewell lament known as ula may predate that epic.[21] The two-brothers theme, more prominent in folktale than dramatic versions of the Nautanki story, similarly has pan-Indian roots.[22] Stock characters like the malin recall the procuress (kutani ) of Sanskrit drama as well as regional folklore. And the motif of changing sex to gain access to a woman is an old one found in medieval Sanskrit fiction.[23]

But there is more than continuity and commonality here. Nautanki shahzadi is a romance, a tale concerned primarily with love and conquests that occur in the region of the heart. Its themes contrast with issues of honor, territory, and war in North Indian martial narratives like the Alha khand . Yet if love is Nautanki's principal focus, it is love with a novel twist. Consider a few anomalous scenes. First, the drama opens with a vituperative refusal by the hero's sister-in-law to supply him with domestic assistance. Her outburst leads to the hero's being launched into exile against the will of his family. Later, at the climax of the first stage of wooing, the princess makes explicit sexual overtures to an attractive young woman (actually Phul Singh in disguise), and at her insistence he eventually joins her in bed. Near the end, the princess charges into her father's court and holds a sword to his neck, threatening his death if her lover is not released. At these junctures, the actions of bold aggressive women dominate the stage, robbing attention from the hero. The very title of the drama suggests that the princess is more important than the male protagonist. Most romances in North India are identified by the names of a pair of lovers, for example, Laila majnun, Benazir badr-e-munir , and Shirin farhad ; but the present story is not remembered as Nautanki phul simh . What does the stress placed on female characters and actions signify?

A close reading of the drama reveals that it is charged with a double-edged eroticism. Incidents, images, and characters repeatedly focus awareness on the pleasures and pitfalls of sexuality. Much as Hirabai, the actress on the Nautanki stage, focuses the spectator's alternating attraction and avoidance, the princess in Nautanki shahzadi functions as a textual concentrate of desire and fear. A difficult, even dangerous, dimension to sexuality first arises in the chastity test, a folklore motif common to Panchphula, Phulpancha, Nautanki, and others. Although these princesses are defined as lightweight, pure, and fairylike in their

virginal state, sexual contact with a man taints them. Loss of chastity literally weighs them down. No longer capable of floating in air, they become heavy and drop down to earth. This dichotomous representation of the weight of the female body proceeds from a cultural proclivity to exalt the chaste presexual woman, raising her to the pedestal of in-substantiality, immortality, and fairyhood, and conversely to regard with dread the gross material nature of the sexual woman. The "heaviness" resulting from sexual contact may allude to the possibility of pregnancy and the ensuing threat to family honor should the woman (like the princess Nautanki) be unmarried. Because of the patriarchal imperative to restrict female fertility, the consequences of inappropriate sexual activity come to be viewed as heavy burdens not only by women but by those males (especially fathers and brothers) who are enjoined with controlling unmarried women's conduct in society.

The fact that the princess is weighed in flowers has further significance within the Indian vocabulary of eroticism. Flowers and other vegetative forms are symbols of fertility in Indian literature, and the mention of flowers in a poem often initiates a romantic mood. Flowers, like body weight, encode a socially and culturally defined ideal of femininity. The notion of a princess light as a flower conjures up the delicate refined beauty prized in the aristocratic female. A cultural practice relevant to the motif of flower weighing is the public weighing of kings and princes on festival occasions (especially birthdays), ordinarily against quantities of gems or coins, as a royal demonstration of wealth and largesse; the coins were afterwards distributed. The flower weighing of the female thus constitutes a declaration of her worth as well as her freshness and excellence; a high price must be paid for her acquisition by a suitable male. The flower imagery does not stop with the chastity test. Phul Singh's name means "flower" (albeit coupled with the martial surname, "lion"), and his meeting with Nautanki takes place soon after his tour around the royal garden. Significantly, he is led by the gardener woman, who guides him on the path to sexual initiation. Where there are flowers, deflowering is not far off.

In the drama's first scene, the potency of Phul Singh's repressed manhood is intimated through the motif of returning from the hunt. (The association of blood lust with sexual lust goes back at least to the Sanskrit drama Sakuntala , where King Dusyanta entered the stage pursuing a deer in a similarly impassioned state.) Immediately upon the play's opening Phul Singh rushes in to his sister-in-law, wife of his elder brother. The relationship between a younger brother (devar ) and his elder broth-

er's wife (bhabhi ) has been classified by anthropologists as a "joking relationship" in North India. The two affinal relatives, more or less equal in age and status, may enjoy a high degree of intimacy. Within this affect-charged bond, the sister-in-law sometimes plays an initiatory role, teasing the unmarried man.[24]

The potentially volatile nature of the devar-bhabhi relationship underlies the start of Nautanki shahzadi . In several versions of the play, the sister-in-law throws her arms about Phul Singh's neck, and in the earliest Khushi Ram edition, she beckons him to come to her and "fulfill her heart's desire." Phul Singh is impatient after his outing and storms in, expecting his sister-in-law to fetch him cold drinking water, prepare his food, provide his smoking materials, and make up his bed so he can relax. He is outraged when she insolently refuses and makes her own suggestive demands. Whereas he has approached her in her nurturing role as maternal surrogate, she counters as a potential sexual partner. The discomfiture of the hero could hardly be clearer.

Subsequently, Phul Singh's sister-in-law recommends he acquire his own wife to serve him. Here she is daring him to prove his maturity and his manhood, which she suggests is not to be achieved by bragging and commanding but rather to be won through a demonstration of valiant effort. Does he succeed in matching her expectation, pursuing the object of his quest and winning Nautanki in a manly way? At first it seems he does. Phul Singh's resolution holds firm as he leaves his home, rides off to Multan, and penetrates the garden of the princess. He gets little chance to show his mettle en route; whatever difficulties he may have surmounted in other versions consist in the extant texts of not knowing the way. Although he manifests more wit than physical strength in making an ally of the malin , he nevertheless succeeds in gaining access to Nautanki's apartment.

As he approaches the object of his desire, however, he moves further from the unalloyed masculinity that would seem essential for the completion of his task. Perfecting the disguise necessary to gain entry, he decorates himself as a bride capable of outdoing even the charms of his beloved. The malin assists him in washing his hair, parting it and applying vermilion, making up his eyes, putting jewelry on his limbs, dressing him in blouse, underskirt, and sari, reddening his mouth with betel leaf, and seating him in a palanquin.

This preparation sets the stage for his entry into the palace and the tremendous peril of his encounter with the princess Nautanki. The play mounts to a high point of comic tension as her uninhibited declarations

of love confront Phul Singh's simultaneous panic and attraction. After all the trials Phul Singh has endured to reach Nautanki, her very forwardness now poses the greatest danger of all. In her state of excessive desire, Nautanki breaches convention and unabashedly approaches a same-sex partner. The crypto-lesbian seduction scene functions in the text to suggest the enormity of the female sexual appetite and simultaneously to titillate the audience with the projection of a male fantasy. Faced with such an aroused, voracious female, Phul Singh is unable to make a sexual conquest. He is reduced to passivity and, calling on his wits again, stages a sham miracle to regain his control and assert his manhood.

Phul Singh eventually accomplishes the deflowering. But as a result of his personal victory he incurs the wrath of the social order, embodied in Nautanki's father, the king. The princess's daily weighing-in betrays the nocturnal rendezvous. Parental authority and societal norms are offended; Phul Singh must be punished. As Phul Singh pledges his willingness to die for love, he seems incapable of mounting any campaign of resistance. Rather than rise up against society's harsh judgment, he waits for Nautanki's return. Finally she enters brandishing a sword. When she threatens to slice off her father's head, the king capitulates and offers the lovers the protection of marriage, the mode of male-female sexual relationship permitted by society.

In these final moments, the heroine Nautanki assumes the stance of the virangana , the warrior woman who protects her people by marching into battle and defeating the enemy. Her authority to rule symbolized in her sword, she is not unlike the powerful goddess Durga, who saved the world by vanquishing the buffalo demon while riding on a lion. The virangana reveals a model of female heroism based not on self-sacrifice and subservience to the male but on direct assumption of power combined with righteousness and adherence to truth (sat ). While North Indian history records the rule of half a dozen queens of this type, folklore and popular culture supply additional instances of a heroine transforming herself into a virangana at a critical juncture.[25]

When princess Nautanki's violent energy bursts out near the end of the play, she is anything but the ethereal fairy whom Phul Singh earlier sought. In opposition to the dainty and virginal image of woman as fairy, her warring and decapitating aspect seems an extension of the sexually aggressive countenance she presented in the courting scene. Nonetheless, it is this overpowering female alone who is effective in saving the condemned Phul Singh. The intervention of the princess as

virangana allows several interpretations. Perhaps this scene replays a male fantasy of bondage and domination by a female. Possibly it is a disguised lament, a metaphorical expression of the individual's powerlessness in major life decisions such as marriage. Or it may be a remnant of goddess worship linked to possession cults. All are plausible in part, but here we note simply the reversal of gendered modes of conduct that has occurred in the course of the drama. Phul Singh, once strong and active vis-à-vis a slight, powerless female, has become feminine in order to accomplish sexual union with her. Now at the marriage he appears weak, passive, ineffectual, while his woman, dressed as a male, is transformed into a "heavy," dominant, victorious warrior.

As in most romantic comedies, the attainment of the love object ends the story. Marriage concludes the play; it symbolizes both the restoration of society's law and the taming of unruly womanhood. In addition it resolves the hero's crisis of maturation that erupted in the initial scene. The two requirements for Phul Singh to develop to maturity were to prove his manhood through sexual conquest and then to learn the proper social place for sexuality, namely subsumed in marriage. These stages correspond to the two steps of courtship in the plot: the initial seduction of Nautanki by Phul Singh and Nautanki's counterseduction of Phul Singh via the rescue. Through this narrative pattern the hero, at first an inexperienced adolescent dependent on an elder brother's wife, is transformed by the end into a proper adult, complete with his own wife.

However satisfying the conclusion of marriage to the narrative's symmetrical design, one suspects that it will not resolve the hero's inner division with regard to women. Will his beloved return to her former docile self, or will he have to make do with a warrior for a wife? The cycle of being attracted to the distant female and avoiding the woman at closer quarters seems destined to replay itself over and over. Summarizing the gender relations contained in Nautankishahzadi , one might say that Phul Singh's saga has consisted of a series of challenges comprised of encountering woman and taming her. It is a series that knows no end, however, for the elusive woman keeps escaping his grasp, threatening to tame him instead.

Implicit in this reading of the text is the premise that woman is consistently represented as object, as the other. The female of the text is seen by the male who occupies the subject position rather than seeing from an independent position as subject. Given the problematics of male sexuality, her image is therefore the eroticized double born of both de-

sire and fear. She oscillates between fairy and warrior, light and heavy, attractive and dangerous—a being essentially alien, outside, and unknown. The male gaze attempts to possess and contain her.

It is this obsession with the otherness of woman, this almost fevered exploration of conflicted male positions in regard to her, that the evidence of the Nautanki shahzadi text suggests is intrinsic to the Nautanki theatre. Beyond the verbal script considered so far, nonverbal dimensions of the Nautanki stage emphatically fix the female body as the locus of this preoccupation (see fig. 3). The erotic dancing, the facial gestures and articulation during singing, the reputation of actresses as prostitutes, and other performative features of Nautanki, guide the spectator's interest unerringly to the women on public display. Not only the Nautanki story, the entire Nautanki theatre revolves around this seductive image of woman. Beguiling, beckoning creature, caricature of men's own craving, she commands the attention of her admirers and dares them to approach.