PART III—

ANIMALS

7—

Common Insects and Other Arthropods

John Smiley and Derham Giuliani

Insects, members of the Phylum Arthropoda (arthropods, or "jointed-legged" creatures), are small animals that usually have six legs and whose adult forms usually bear wings. They are the most varied group of organisms on Earth; nearly a million species have been described. Insects are primarily terrestrial, although many inhabit freshwater streams, ponds, and lakes. In the oceans, insects are replaced by their relatives, the crustaceans. Other arthropods common in terrestrial habitats are the spiders, mites, ticks, and scorpions (collectively known as arachnids); a few species of terrestrial crustaceans, such as pillbugs and sowbugs; and the centipedes and millipedes. This chapter emphasizes species of insects but also lists and illustrates other types of arthropods commonly encountered in the vicinity of the White Mountains.

The small size and great diversity of arthropods make determination of species difficult; therefore, it is usually a job for experts. However, recognition of major groups is not difficult, and one can obtain as much satisfaction from recognizing a particular family or order as from identifying an interesting bird species. For example, identifying an insect family provides information about the intricate (and commonly fascinating) life cycle of the insect in question, its relations with its environment, and its interactions with other species of plants and animals. In our discussions of major groups, we encapsulate some of the more interesting facets of arthropod life history along with species distributions and aids to identification. Names are given for some of the more common, large species, most of which are illustrated as well. Our selection is necessarily somewhat arbitrary, because we have neither the space nor the collected material to systematically list species or even genera. Useful books to aid in insect identification are California Insects by J. A. Powell and C. H. Hogue, the Peterson Field Grade to the Study of Insects by D. J. Borror and C. L. White, and Introduction to the Study of Insects by D. J. Borror, D. M. Delong, and C. A. Triplehorn.

Most terrestrial arthropods are small, but adult individuals range considerably in size, depending on the amount of food available during the juvenile stages. For this reason, and because we wish to emphasize major groups rather than species, we do not report sizes for most species. Instead, we indicate size in general terms. "Large" generally refers to insects over 0.4 in (10 mm) in length, and "small" refers to insects under 0.2 in (4 mm) long.

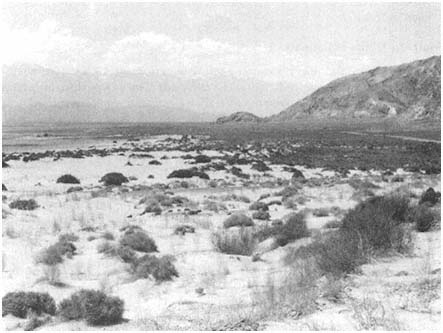

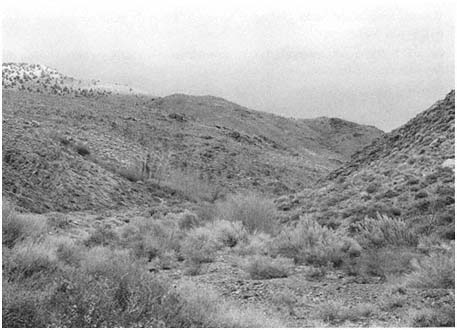

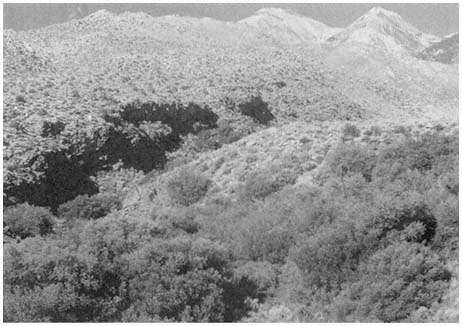

Most of the species discussed in this chapter occur along the road from Big Pine to Westgard Pass, or from there up the road to the Bristlecone Pine forest and

the Barcroft facilities of the White Mountain Research Station (WMRS). Many of the species occur in the vicinity of the Crooked Creek facilities (WMRS), at 10,150 ft (3,094 m), Barcroft Laboratory, at 12,470 ft (3,801 m), and White Mountain Peak, at 14,250 ft (4,343 m). Most species listed as occurring at low elevations are present in the vicinity of the Owens Valley facilities (WMRS), 3 mi (5 km) east of Bishop, California.

Spiders, Mites, Ticks, Scorpions, and Others:

(Class Arachnida)

Arthropods of the Class Arachnida generally bear eight legs, and the head and thorax are usually fused into a single body section, the cephalothorax. The arachnids generally prey on other arthropods (e.g., spiders), but some are herbivorous (e.g., Spider Mites) and others are parasitic (e.g., ticks). Still other types feed on decaying matter.

Scorpion (Order Scorpiones)

Scorpions (Fig. 7.1) are common at lower elevations and are generally nocturnal. These predaceous arthropods have a stinger at the tip of the tail-like abdomen and should be handled with care. Smaller forms are common around houses and woodpiles.

Spiders (Order Araneae)

The spiders are a diverse group of predatory arthropods. In many habitats they are extremely abundant and consume vast numbers of tiny insects and other small prey. They are also a favorite food of many birds and other insectivorous vertebrates.

Tarantulas (Family Theraphosidae). (Fig. 7.1) Large spiders with very hairy bodies. Although the Tarantula can bite, North American species are relatively harmless. Tarantulas are nocturnal and serve as prey for several large spider-killing wasps, including those of the genus Pepsis . During the day they hide in silk-lined burrows in the ground.

Black Widow Spider,Latrodectus hesperus(Family Theridiidae). (Fig. 7.1) Produces tangled webs made of exceptionally strong, thick silk, commonly occur in buildings and sheds. The female is black with an hourglass-shaped red patch on the underside. The venom is very toxic, and bites should be treated medically. Black Widows are known to catch their prey by "spitting" strands of silk, entangling it.

Orb-weaving Spiders (Family Araneidae). (Fig. 7.1) A large family of spiders that weave the familiar circular "orb" web, which is used to catch flying insect prey.

Wolf Spiders,Lycosaspp. (Family Lycosidae). (Fig 7.1) Terrestrial hunters, often abroad by day. The females of these hairy brown spiders are commonly seen carrying a large, spherical egg case or newly hatched young on their back. Small Wolf Spiders

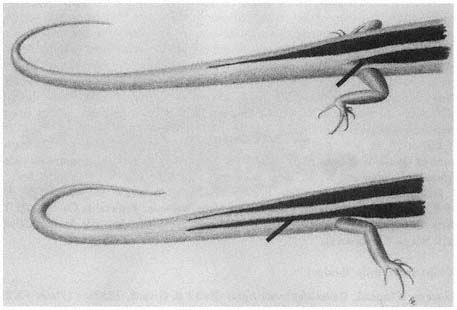

Figure 7.1

Non-insect arthropods: arachnids, sowbugs, centipedes, and millipedes.

may be extremely abundant in grasslands and meadows up to 14,000 ft (4,300 m) elevation.

Jumping Spiders (Family Salticidae). (Fig. 7.1) An easily recognized family of spiders with very short legs, which they use to rapidly run and jump in search of their prey. Diurnal, they have large eyes and hunt their prey visually, jumping on it and delivering a paralyzing bite. Some species are brightly colored with red, metallic green, or blue.

Harvestmen (Order Opiliones)

Harvestmen have the entire body fused into a circular or oval shape and commonly have very long legs. Most species are predaceous.

Daddy Longlegs (Suborder Palpatores). (Fig. 7.1) Some Daddy Longlegs huddle together in masses of hundreds in cool, damp spots, their legs resembling masses of brown hair.

Mites and Ticks (Order Acarina)

Mites and ticks are usually small, with very short legs as compared with spiders. They have sucking mouthparts.

Ticks (Families Ixodidae and Argasidae). (Fig. 7.1) Ticks are blood-sucking parasites of vertebrates, to which they attach themselves and feed until they are engorged. In large numbers they may cause temporary paralysis until removed. Tick bites can become infected, particularly when a feeding tick is removed carelessly, its head broken off and left in the wound. Ticks also serve as vectors for disease.

Red-spider Mites (Family Tetranychidae). (Fig. 7.1) An important group of extremely tiny arthropods (less than 0.04 in or 1.0 mm) that are herbivorous, causing severe economic damage to certain crops and cultivated plants, particularly indoors. They are slow-moving and sedentary. Other mites, larger and more active, are predaceous and commonly seen at all elevations on the ground and in foliage. They are usually red or orange.

False Scorpions, or Pseudoscorpions (Order Pseudoscorpiones)

False Scorpions (Fig. 7.1) are small arthropods that lack the tail-like stinger of true scorpions but possess a pair of pincers and otherwise look very much like true scorpions. These animals overwinter under stones and logs, in a silken case.

Wind Scorpions (Order Solifugidae)

Wind Scorpions are a group of large, conspicuous athropods. They are fast-running predators chiefly active at night.

Sun Spiders. (Fig. 7.1) Yellow-brown arachnids that look like large spiders except that the abdomen is segmented, like that of a scorpion, and the head bears large, foreward-facing jaws. They do not produce venom.

Isopods:

(Class Crustacea)

The Class Crustacea is an extremely diverse group of arthropods found primarily in aquatic or marine habitats, including such forms as shrimp, crabs, lobsters, and barnacles. Only one group, the isopods, have invaded terrestrial habitats.

Sowbugs (Order Isopoda). (Fig. 7.1) The Sowbug is a widespread, extremely successful crustacean. Sowbugs have a gray-black segmented carapace, have seven

pairs of legs, and are commonly seen around habitations or where the ground is watered. Some are capable of rolling up into a ball and are known as pillbugs.

Millipedes:

(Class Diplopoda)

Millipedes are long, wormlike arthropods with two pairs of legs on each body segment and commonly 60–100 legs overall. Usually occurring in damp places, millipedes are generally scavengers and do not bite.

Cylindrical Millipedes (Order Opisthospermophora). Cylindrical millipedes (Fig. 7.1) are relatively large and have a hard shell. They occur in leaf litter and on the ground.

Centipedes:

(Class Chilopoda)

Like millipedes, centipedes are long and slender and composed of many segments. Unlike millipedes, centipedes bear only one pair of legs per segment and are predaceous, actively running and seeking out prey. Larger individuals are capable of delivering a painful bite.

Centipedes (Several orders). Centipedes (Fig. 7.1) range from small to very large (up to 6 in long) and are capable of biting or pinching with both their mandibles and their tail appendage. The venom is generally not toxic in North American species.

Insects:

(Class Insecta)

Insects have an inelastic, external skeleton that must be shed as the animal grows. After hatching from the egg, a typical insect undergoes a fixed number of moults until it reaches adulthood; the stages between moults are called instars. When the insect reaches the adult stage, it may develop wings; this change is called metamorphosis. Juvenile insects never have wings. Adult insects are capable of reproduction but not of growth since no further moults are possible. Thus, a small insect with wings is a fully formed adult and will grow no further, whereas a large insect without wings may be a juvenile or, in some cases, a wingless adult. In insects with incomplete metamorphosis, the juveniles resemble the adults and are usually called nymphs. In species with complete metamorphosis, the juveniles differ greatly from the adult and are usually called larvae (singular: larva). Figure 7.2 illustrates these differences.

Because they are small, insects cannot store large amounts of water, food, or heat in their bodies. Under ideal growth conditions insects grow and multiply rapidly, but they must pass seasons of cold or drought by hiding in a state of dormancy, or

Figure 7.2

Complete and incomplete metamorphosis.

diapause. In the White Mountains region, most insects are active in the springtime and dormant during the dry summers and the cold winters. Other insects are active in the summer and fall, and a few species are adapted to cold conditions, active on melting snow or under the snow during the winter months. Owing to differences in the regimes of temperature and moisture at different elevations, the period of spring activity begins in March or April in the Owens Valley, but this period does not begin at Barcroft or White Mountain Peak until July or August. There "spring" commonly lasts until the first snows in September or October.

Figure 7.3 illustrates the external anatomy of a typical insect, a grasshopper. An insect has a head, thorax, and abdomen. The head contains the eyes, which may be simple or compound (i.e., composed of hundreds of simple eyes). Also on the head is a single pair of segmented antennae. They are primarily used for detecting odors, although some species with long antennae may use them as "feelers" for detecting objects or vibrations. The head also bears the mouthparts, including mandibles (jaws), maxillae, and various jointed palps for manipulating food. During the course of evolution, insect mouthparts have taken many different forms, including piercing "syringes," beaks, and coiled tubes. Each group of insects has characteristic mouthparts that are very useful in identification.

The thorax consists of three segments: the prothorax, mesothorax, and metathorax from front to back, each of which bears a pair of legs. The top of each segment is protected by a hardened plate. In addition to legs, the meso- and metathorax each bear a pair of wings in most adult insects. The anterior wing is called the

Figure 7.3

External anatomy of a grasshopper.

forewing, and the posterior the hindwing. The wings of insects are membranous, with a framework of rigid veins. The arrangement of these veins is very important in insect identification.

A typical insect leg has four visible jointed segments: the coxa, femur, tibia, and tarsus. The coxa is usually rounded and attached to the body. The femur usually extends out from the body and is the first long segment. The tibia usually extends downward from the femur, nearly touching the substrate. The tarsus functions like a foot, with claws, hairs, and pads for clinging to surfaces. The tarsus is itself composed of several segments, the number of which is useful in identification.

The abdomen of insects usually has 6 to 10 visible segments. The upper (dorsal) and lower (ventral) surfaces of each segment may bear hardened plates, but in some species the abdomen is soft. The posterior end of the abdomen bears the anal opening, appendages for copulation, and, in female insects, the ovipositor for laying eggs. In a few insects, such as grasshoppers, roaches, and related groups, a pair of sense organs are borne on the upper surface of the posterior end of the abdomen. These are called cerci (singular: cercus).

The Class Insecta is divided into approximately 20 orders and 750 families, 500 of which occur in North America. In this natural history guide we introduce most of these orders and a few of the most easily distinguished families occurring in the White Mountains. Because there may be as many as 5,000 to 10,000 insect species present in the region, we can only present a sampling of the most common and interesting species. The only large group that is nearly completely represented here is that of the butterflies, for which identification may be accomplished by reference to the color plates.

Dragonflies and Damselflies (Order Odonata)

Members of the Order Odonata are easily recognized in the adult form. Species that hold their wings extended laterally when resting are known as Dragonflies (Suborder Anisoptera), and species that hold their wings pressed together dorsally at rest are

Figure 7.4

Life stages of a dragonfly.

known as Damselflies (Suborder Zygoptera). These insects are predators, capturing other insects in flight with their basketlike legs. Individuals copulate in flight and frequently are seen flying in tandem, with the male clasping the female behind the head using appendages at the tip of his abdomen. The female may also lay eggs in the water while in tandem with the male. The nymphs live in fresh water, where they are predators of small animals. Adults are common on the floor of the Owens Valley and have been recorded as high as White Mountain Peak, at over 14,000 ft (4,300 m). Figure 7.4 illustrates the life stages of dragonflies.

Green Jacket Dragonfly,Erythemis simplicicollis(Family Libellulidae). Occurs from the Owens Valley floor to Crooked Creek (10,000 ft, or 3,100 m). The large, green adults fly in July and August, commonly at some distance from water.

Figure 7.5

Dancer Damselfly (Argia sp.).

Dancers,Argiaspp. (Family Coenagrionidae). (Fig. 7.5) Damselfly genus occurs from the Owens Valley Floor to Crooked Creek (10,000 ft, or 3,100 m), usually near water.

Termites (Order Isoptera)

Termites are highly social insects. Some species can be very destructive due to their feeding activities on wooden structures. They are soft-bodied, are whitish in color, and live in large colonies with a well-defined caste system. Their gut contains diverse symbiotic microorganisms that aid in the digestion of wood.

Dampwood Termites,Zootermopsisspp. (Family Hodotermitidae). (Fig. 7.6) Occupy dead logs and stumps, especially places where wood is damp. Another termite, the Subterranean Termite (Reticulotermes spp.), does not occur at relatively high elevations in the White Mountains but is present in the Owens Valley, where it can damage structural wood in contact with the soil.

Grasshoppers, Roaches, Mantids, and Related Groups (Order Orthoptera)

The Order Orthoptera is a highly diverse group, including many large, common species. The crickets, katydids (Family Tettigoniidae), and grasshoppers (Family Acrididae) are primarily herbivorous and have enlarged, powerful hind legs that enable them to jump (see Fig. 7.3). Many grasshoppers take flight during their jump and display brightly colored wings, which carry them up to 100 ft (30 m). The roaches, which have long antennae and long abdominal cerci, are primarily nocturnal scavengers. The phasmids, or walking sticks, are herbivorous. The mantids are highly

Figure 7.6

Dampwood Termite

(Zootermopsis sp.).

predaceous, with forelegs modified into striking claws that can grab prey with lightning speed.

Most adult orthopterans are winged, including roaches, but some species of montane grasshoppers and crickets are flightless. Crickets, katydids, and grasshoppers commonly possess sound-producing organs on their legs and wings; in most species the males produce trilling, buzzing, or clicking sounds that attract females for mating. Grasshoppers are common in open, dry habitats and are well-represented in the White Mountain region. Here is also present a flightless species (Agnostokasia sublima ) that occurs nowhere else.

American Cockroach,Periplaneta americana(Family Blattidae). (Fig. 7.7) A house and yard pest species that occurs at lower elevations in the Owens Valley. They apparently do not reach Crooked Creek, at 10,000 ft (3,100 m).

Short-horned Grasshoppers (Family Acrididae). Short-horned Grasshoppers may be recognized by their antennae, which are much shorter than the body. Many species have brightly colored wings, visible in flight.

Migratory Grasshopper, Melanoplus sanguinipes . (Plate 7.1) Commonly present in swarms between 11,000 and 13,000 ft (3,300 and 4,000 m). At lower elevations it rarely occurs in large numbers but can be a devastating crop pest when it does.

Pallid-winged Grasshopper, Trimerotropis pallidipennis . (Plate 7.1) Occurs in the Owens Valley at elevations as high as 5,000 ft (1,500 m).

Sierran Blue-winged Grasshopper, Circotettix thalassinus . Common at middle elevations (6,000–9,000 ft, 1,800–2,700 m), where males display by flying up and making loud popping or crackling noises.

Agnostokasia sublima . (Plate 7.1) Known only from 12,000 to 13,000 ft (3,600 to 4,000 m) in the White Mountains, including Barcroft area. A flightless species.

Mormon Cricket,Anabrus simplex(Family Tettigoniidae). (Plate 7.1) Occurring near Crooked Creek and near Barcroft, 10,000–12,000 ft (3,000–3,600 m), always associated with sagebrush (Artemisia ). Flightless, the males call in late morning with a loud stridulation. This species is a member of a subfamily of crickets (the Decticinae)

Figure 7.7

American Cockroach (Periplaneta americana ).

that is very diverse in the Owens Valley region. Known as the Shield-backed Katydids, Decticinae are commonly flightless, especially the females.

Camel Cricket,Ceuthophilus lamellipes (Family Gryllacrididae). (Fig. 7.8) Occurs from the Owens Valley to elevations of 11,000 ft (3,400 m), usually present under stones and logs.

California Mantid,Stagmomantis californica(Family Mantidae). (Fig. 7.9) Occurs in Owens Valley up to higher elevations. Mantids have been collected at Crooked Creek, at 10,150 ft (3,100 m), but not at higher sites.

True Bugs (Order Hemiptera)

Members of the Order Hemiptera, or true bugs, possess a slender, segmented beak, arising from the anterior tip ("forehead") of the insect, and front wings divided into two parts, with the basal portion thick and leathery and the rest transparent. The antennae are fairly long and consist of four or five segments. Many hemipterans have scent glands, which give off an acrid scent when the insect is disturbed. Juvenile hemipterans look like the adults, except they lack wings. Juveniles eat the same food as the adults and occur in the same habitats. Most species feed on plant juices, and some are considered serious pests. Other hemipterans are considered beneficial to man because they attack harmful insects. Still other hemipterans suck blood, and a few of these insects act as vectors for disease. Some hemipterans resemble ants in appearance and mode of walking, presumably to deceive their predators.

Say's Stink Bug,Chlorochroa sayi (Family Pentatomidae). (Fig. 7.10) Green bugs widespread and common in the White Mountains from 4,000–14,000 ft (1,200 to 4,300 m). They can be found feeding on a variety of plants from spring to fall.

Figure 7.8

Camel Cricket (Ceuthophilus

lamellipes ).

Figure 7.9

California Mantid (Stagmomantis

californica ).

Figure 7.10

Say's Stink Bug

(Chlorochroa sayi ).

Figure 7.11

Big-eyed Bug

(Geocoris bullatus ).

Big-eyed Bug,Geocoris bullatus(Family Lygaeidae). (Fig. 7.11) Abundant, very small insect occurring in the Mount Barcroft area under low vegetation, where it probably eats seeds and soft-bodied insects.

Alydus pluto(Family Alydidae). (Plate 7.1) The bright red-orange abdomen shows in flight but is covered by dark wings when the insect is at rest. Common at middle elevations (6,000–10,000 ft; 1,800–3,100 m). Nymphs resemble ants and feed on plants.

Common Milkweed Bug,Lygaeus kalmii (Family Lygaeidae). (Plate 7.1) A common member of the Seed Bug Family that occurs at elevations as high as 11,000 ft (3,400 m) in the White Mountains. Red with black markings, this bug prefers milkweed seeds for its food but will also feed on a wide range of other plants.

Cicadas, Leafhoppers, Aphids, Scale Insects, and Others (Order Homoptera)

The large and diverse Order Homoptera is related to the Order Hemiptera. Homopterans exhibit a large variation in body structure, but the most distinguishing characteristic is the beak, which is located near the insect's neck (on the "chin"). The antennae are very short and bristlelike, and the compound eyes are usually large. Winged homopterans usually have four membranous wings, which at rest are usually held rooflike over the body.

All homopterans feed on plant sap, and many species are serious pests of cultivated plants. A few homopteran species are beneficial, used to make shellac, dyes, and other materials.

Giant Willow Aphid,Tuberolachnus salignus(Family Aphididae). (Fig. 7.12) An aphid common on willows (Salix spp.) in the region, feeding in large colonies on the trunks and branches. Also known as Plant Lice, members of the Aphid Family

Figure 7.12

Grant Willow Aphid

(Tuberolachnus salignus ).

Figure 7.13

Scale insect.

are sedentary insects that feed on plant sap. Many aphids are "tended" by ants, which obtain sugary "honeydew" excretion in return for protection from enemies such a Ladybird Beetles and maggots (larvae) of Syrphid Flies. Adult aphids may be winged sexual reproductives or wingless females that reproduce parthenogenically (i.e., without mating). Aphids may occur at all elevations in the White Mountains.

Scale insects (Family Coccidae). (Fig. 7.13) The body of a scale insects is hidden under a waxy shell that resembles fish Scales attached to the bark of trees and shrubs. Some species secrete honeydew and are tended by ants. They occur in the Owens Valley, and probably on trees and shrubs at elevations below 12,000 ft (3,700 m).

Leafhoppers (Family Cicadellidae). (Fig. 7.14) Occurring at all elevations in the White Mountains, Leafhoppers are highly active homopterans that live on twigs of trees, shrubs, and herbs. Usually cylindrical and bullet-shaped, many Leafhoppers have the habit of quickly moving to the opposite side of the twig when approached so as to be shielded from view.

Cicadas (Family Cicadidae). (Fig. 7.15) Occur at elevations below 12,000 ft (3,700 m). Usually heard but not seen, most male cicadas produce a loud, musical buzz or whine that is easily distinguished from the trills and intermittent buzzes/clicks of most orthopterans. Cicadas are large-bodied, and the juveniles feed underground on

Figure 7.14

Leafhopper.

Figure 7.15

Cicada.

plant roots for two to five years. One species, Okanagana cruentifera , is locally very abundant in sagebrush (Artemisia ).

Beetles (Order Coleoptera)

The Order Coleoptera contains about 40% of all known insect species. Beetles occur in virtually every habitat except the ocean. The wings are the most distinguishing characteristic of Coleoptera. The hard, shell-like front pair, called elytra, are used mainly for protection. The second pair of wings, membranous and longer than the elytra, are used for flying and are folded under the elytra when not in use. Beetles have chewing mouthparts and undergo complete metamorphosis. Overwintering can occur at any stage of development, depending on the species. The larvae vary considerably in form among different families. Beetles and beetle larvae are known to feed on all types of plant and animal materials. Many beetles are considered valuable because they destroy injurious insects or act as scavengers.

Tiger Beetles,Cicindelaspp. (Family Cicindelidae). (Fig. 7.16) Very active, predaceous beetles commonly seen at elevations up to 12,000 ft (3,700 m). They may be metallic green, blue, or plain brown, but their colors are difficult to see because they move so rapidly. Two species, C. plutonica and C. montana, are common at high elevations (11,000–12,000 ft, 3,300–3,700 m).

Ground Beetles,Pterostichusspp. (Family Carabidae). (Fig. 7.17) Occurs near 9,000 ft (2,700 m) in July. Ground Beetles are common insects that forage for prey mainly on the ground. Species are often similar in shape but may differ greatly in size. They are usually black or brown and have fine "lines" on the wing covers parallel to the margins. There are very many species. Another genus that occurs in the White Mountains is Callisthenes, near 10,000 ft (3,100 m) in July and August.

River Beetle,Agabus lutosus(Family Dytiscidae). (Fig. 7.18) A water beetle that commonly occurs in small ponds at elevations up to 12,500 ft (3,800 m). Both the larvae and the adults are predaceous.

Figure 7.16

Tiger Beetle (Cicindela sp.).

Figure 7.17

Ground Beetle

(Pterostichus sp.).

Figure 7.18

River Beetle

(Agabus lutosus ).

Figure 7.19

Serica sp.

Burying Beetle,Nicrophorus hecate (Family Silphidae). (Plate 7.1) Two varieties — one black, the other red and black — are found on carrion from 4,000 to 10,000 ft (1,200 to 3,100 m), from spring to fall. These beetles bury small carrion, remove the hair, and feed and lay eggs in an underground chamber.

Sericaspp. (Family Scarabidae). (Fig. 7.19) Occurs near 8,000 ft (2,400 m) elevation in summer, commonly on trees and shrubs.

Twig Girdler,Agrilus walshinghami (Family Buprestidae). (Fig. 7.20) Occurs from 4,000 to 6,000 ft (1,200–1,800 m) in August and September on flowers of Rabbit Brush Chrysothamnus nauseosus .

Cactus Flower Beetles,Carpophilusspp. (Family Nitulidae). (Fig. 7.21) Occur in cactus flowers at lower elevations (4,000–9,000 ft, 1,200–2,700 m) in spring.

Common Checkered Beetle,Trichodes ornatus(Family Cleridae). (Fig. 7.22) Commonly occurs on flowers, including cactus flowers, and probably occurs up to 10,000 ft (3,100 m).

Blister Beetles (Family Meloidae). A family of beetles common and diverse in the low-elevation areas of the Owens Valley. Many are brightly colored. Eggs are laid on

Figure 7.20

Twig Girdler

(Agrilus

walshinghami ).

Figure 7.21

Cactus Flower Beetle

(Carpophilus sp.).

Figure 7.22

Common Checkered

Beetle (Trichodes

ornatus ).

the ground or on flowers, and the first instar larvae actively seek out host insects such as bees or grasshopper eggs, feeding on the host eggs and larvae.

Meloe spp. May occur up to 12,000 ft (3,700 m). The larvae are parasites of bees.

Epicauta oregona . A small and grey species with black spots that occurs in the Owens Valley. Its larvae probably feed on grasshopper eggs.

Soldier Blister Beetle, Tegrodera latecincta . (Plate 7.1) A large meloid occurring in the Owens Valley and up into the foothills to 4,500 ft (1,400 m). This and the following two species may be seen feeding on flowers in summer.

Pleurospasta mirabilis . (Plate 7.1) Occurs below 5,000 ft (1,500 m) in the Owens Valley.

Phodaga alticeps . (Plate 7.1) Occurs below 5,000 ft (1,500 m) in the Owens Valley.

Armored Stink Beetle,Eleodes armatus (Family Tenebrionidae). (Plate 7.1) A large, black beetle that occurs commonly during all seasons from 4,000 to 7,000 ft (1,200 to 2,100 m), where it is usually found walking on open ground. When disturbed, it raises the tip of its abdomen into the air, sometimes emitting a foul-smelling vapor. These beetles superficially resemble Ground Beetles (Family Carabidae), but their behavior and the lack of prominent jaws are usually sufficient to distinguish the two families. Other common species include Eleodes obscura, which occurs from 5,000 to 8,000 ft (1,500 to 2,400 m), spring to fall; Eleodes pilosa, at 10,000 ft (3,100 m) in July; and Eleodes (Blapylus) species, which occur from 10,000 to 13,000 ft (3,100 to 4,000 m) in summer and fall.

Convergent Ladybird Beetle,Hippodamia convergens(Family Coccinellidae). (Plate 7.1) A familiar beetle occurring at all elevations. Thousands of "ladybugs" may locally occur clustered in watered canyons or on mountain peaks, especially in fall and winter. This and the following species are important predators of other insects, especially homopterans.

Neomysiaspp. (Family Coccinellidae). Occurring from 6,000 to 9,000 ft (1,800 to 2,700 m), pale, faintly striped species montane in distribution and common on Pinyon Pine.

Leaf Beetles,Alticaspp. (Family Chrysomelidae). Small (0.1 in, 3mm) metallic blue or purple beetles common at higher elevations (10,000–12,000 ft, 3,100–3,700 m). Members of this abundant, diverse family are commonly green, blue, or black and resemble the ladybird beetles in shape. They are commonly very small and feed primarily on the leaves of plants. Also common are the Trirhabda species, whose irridescent green larvae feed on sagebrush.

Long-horn Beetles (Family Cerambycidae). Adult beetles of the Family Cerambycidae have thick, long antennae and so are collectively known as "long-horn beetles." Larvae of most species bore into wood.

Figure 7.23

Banded Alder Borer

(Rosalia funebris ).

Banded Alder Borer, Rosalia funebris . (Fig. 7.23) A large, conspicuous beetle that occurs along Owens River, where its larvae bore into alder, willow, and other hardwood trees.

Crossidius hertipes nubilis . (Plate 7.1) Occurs from 7,000 to 8,000 ft (2,100 to 2,400 m), where it is commonly seen feeding on flowers of Rabbit Brush Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus .

Arhopalus asperatus . A large, black cerambycid whose larvae bore into pine and other conifers.

Judolia instabilis . (Plate 7.1) Commonly occur on flowers, especially lupine. Larvae bore into pine species. Adults of this species may be yellow and black, or all black. Occurs from 7,000 to 13,000 ft (2,100 to 4,000 m).

Butterflies and Moths (Order Lepidoptera)

Lepidoptera is a familiar group of insects commonly known as butterflies and moths. The adults possess minute scales on their wings that, in many species, produce brilliant color patterns. The mouthparts are modified into a thin, coiled tube through which they drink fluids. Most butterflies have six functional legs, but adults of one family, the Nymphalidae, possess only four.

Lepidoptera are almost entirely herbivorous: only in the larvae stage, when they are known as caterpillars, do they eat solid food. They are voracious eaters and can quickly defoliate a plant, particularly when feeding in groups. Lepidopteran caterpillars can be recognized by the gap (of at least two segments) between their thoracic "true" legs and their abdominal "prolegs," which are not jointed legs but simply extensions of the abdominal body wall. Other insect larvae that might be mistaken for Lepidoptera

caterpillars either: (1) have prolegs on every abdominal segment (Sawflies, of the Order Hymenoptera), (2) lack prolegs except for an anal "clasper" (Ladybird and Leaf Beetles, of the families Coccinellidae and Chrysomelidae, respectively), or (3) lack thoracic legs entirely (Hover flies, of the Family Syrphidae).

Most adult moths are gray or brown and are easily distinguished from butterflies, which are usually brightly colored. However, there are some exceptions. In such cases, butterflies may usually be distinguished by the presence of clubbed antennae, unlike the usual hairlike or plumose antennae of moths.

Lepidoptera, particularly the butterflies, are a favorite of collectors. Consequently, their habits and distributions are relatively well known. Most species of butterfly are brightly colored and may be recognized by comparison with drawings or photographs; we have included most of the species known from the White Mountain area in Plates 7.1–7.5. Good specimens of most butterflies may be obtained by locating the caterpillars and raising them to adults in a jar or plastic bag, feeding them leaves of the host plant they were found upon.

Tent Caterpillar,Malacosoma americana (Family Lasiocampidae). Commonly weaves large, conspicuous "tents" of silk in shrubs belonging to the Rose Family (locally plants in other families are used). Each tent contains 50 or more caterpillars. The adults, plain brown moths, occur in desert scrub up to 9,000 ft (2,700 m).

White-lined Sphinx Moth,Hyles lineata (Family Sphingidae). (Plate 7.2) Occurs up to 13,000 ft (4,000 m) in spring, summer, and fall. These moths are commonly attracted to lights at night, sometimes in large numbers, and may be seen visiting flowers at dusk or on overcast days.

Skippers (Family Hesperiidae). Skippers derive their common name from their rapid, "skipping" flight, usually seen when they visit flowers. At rest, many male skippers do not fold their wings together over their back but hold them at an angle, with the fore- and hindwings separated. Many skipper caterpillars feed on monocot plants, such as grasses, and are green or brown with very large heads.

Common Sootywing, Pholisora catullus . (Plate 7.2) Found at 6,000 ft (1,800 m) in May. Larvae feed on pigweeds such as Chenopodium and Amaranthus .

Great Basin Sootywing, Pholisora libya lena . (Plate 7.2) Adults occur at 6,000 ft (1,800 m) in June.

Sandhill Skipper, Polites sabuleti tecumseh . (Plate 7.2) Adults occur from 10,000 to 13,000 ft (3,100 to 4,000 m) in the summer. Larvae feed on grasses such as Distichlis and lawn grass.

Sierra Skipper, Hesperia miriamae . (Plate 7.2) Adults occur from 13,000 to 14,000 ft (4,000 to 4,300 m) during the summer. Larvae of this high-altitude species probably feed on grasses.

Uncas Skipper, Hesperia uncas macswaini . Looks like H. miriamae but with a dusky border on the upper surface of the hindwing. It flies at very high elevations in the

White Mountains, in grassy areas in June and July. Larvae feed on Needlegrass Stipa nevadensis .

Common Banded Skipper, Hesperia comma harpalus . (Plate 7.2) Occurs from 4,000 to 14,000 ft (1,200 to 4,300 m) from spring to fall. Larvae feed on grasses and sedges.

Juba Skipper, Hesperia juba . (Plate 7.2) May occur from 6,000 to 10,000 ft (1,800 to 3,100 m) in summer. Larvae feed on grasses.

Mexican Cloudy-wing, Thorybes mexicana blanca . A skipper medium brown in color, with black-bordered white spots on the forewing. It occurs above 7,000 ft (2,100 m) in June–August. Larval food plants are unknown.

Whites and Sulfurs (Family Pieridae). As their names suggest, Whites and Sulfurs are butterflies that are usually white or yellow in coloration. They are typically fragile animals, losing their legs and scales easily. They have six functional legs. The caterpillars are mostly green or yellow-green, lack long spines or hairs, and feed on plants in the Mustard and Caper families (White Butterflies) or in the Legume Family (Sulfur Butterflies).

Cabbage White, Pieris rapae . A species common around gardens and fields on the Owens Valley floor and occasionally at higher elevations. It has whitish or yellowish underwings, in contrast to the other whites of the region, which have dark markings below.

Checkered White Butterfly, Pontia protodice . (Plate 7.2) The underside has relatively few brownish markings. Occurs from 4,000 to 14,000 ft (1,200 to 4,300 m) from spring to fall. Larvae feed on plants in the Mustard Family (Brassicaceae).

Becker's White Butterfly, Pontia beckerii . (Plate 7.2) A white with black spotting on the tips and margins of the forewings; the undersides of the wings have greenish brown markings. Adults occur from 4,000 to 8,000 ft (1,200 to 2,400 m) in June and July. Larvae feed on mustard plants such as the Black Mustard (Brassica nigra ).

Hyantis Marble Butterfly, Euchloe hyantis lotta . (Plate 7.2) A small white with green markings on the underside of the wings. The adults occur from 4,000 to 8,000 ft (1,200 to 2,400 m) in May. Larvae feed on several species of mustard.

Orange Sulfur, Colias eurytheme . (Plate 7.2) Occurs from 4,000 to 14,000 ft (1,200 to 4,300 m) from spring to fall. Larvae feed on several species of plants in the Legume Family, including alfalfa (Medicago spp.), clover (Trifolium spp.), vetches and locoweeds (Astragalus spp.), and lupines (Lupinus spp.).

Swallowtails (Family Papilionidae). Members of the Family Papilionidae derive their common name from the "tails" attached to the hindwing. Swallowtails are large, sturdy butterflies, usually black and yellow. They are commonly seen gliding

Figure 7.24

Western Tiger Swallowtail

(Papilio rutulus ).

effortlessly across open ground, visiting flowers and searching for host plants. Adults have six legs.

Western Tiger Swallowtail, Papilio rutulus . (Fig. 7.24) Commonly occur in watered canyons and around towns. Larvae feed on willow, poplar, and sycamore trees.

Short-tailed Black Swallowtail, Papilio indra nevadensis . (Plate 7.3) Adults occur from 6,000 to 9,000 ft (1,800 to 2,700 m) in June. Larvae usually feed on plants in the Carrot Family (Apiaceae), but they are also known to feed on sagebrush (e.g., Artemisia tridentata ).

Blues and Coppers (Family Lycaenidae). Lycaenidae is a family of butterflies diverse in the White Mountains region, and many of its members are associated with ants in various ways. The caterpillars are sluglike, with a thick skin that is resistant to ant attack. Some species have glands and pores that secrete nectar and amino acids. This functions to attract a protective "guard" of ants, much in the way that many homopterans attract ants. For unknown reasons, male lycaenids have somewhat reduced forelegs compared with the females, which have six functional legs.

Mormon Metalmark Butterfly, Apodemia mormo . (Plate 7.3) Occurs from 4,000 to 7,000 ft (1,200 to 2,100 m) in the fall. Larvae feed on buckwheat (Eriogonum spp.).

Edward's Blue, Plebejus (Lycaeides) melissa paradoxa . (Plate 7.3) Occurs from 4,000 to 11,000 ft (1,200 to 3,400 m) in the summer. The larvae feed on species in the Legume Family, including lupines, vetches, and locoweed (Oxytropis spp.).

Greenish Blue, Plebejus saepiolus . (Plate 7.3) Occurs at 12,000 ft (3,700 m) throughout the summer. Larvae feed on clover (Trifolium spp.).

Boisduval's Blue, Plebejus (Icaricia) icarioides . (Plate 7.3) Occurs from 9,000 to 12,000 ft (2,700 to 3,700 m) during the summer. Larvae feed on lupine (Lupinus spp.).

Alpine Blue, Plebejus shasta . (Plate 7.3) Occurs from 10,000 to 13,000 ft (3,100 to 4,000 m) during the summer. Larvae feed on lupines, clover, and locoweed (e.g., Astragalus ).

Lupine Blue, Plebejus lupini . (Plate 7.3) Occurs from 10,000 to 13,000 ft (3,100 to 4,000 m) during the summer.

Acmon Blue, Plebejus acmon . (Plate 7.3) Adults occur from 4,000 to 11,000 ft (1,200 to 3,400 m) in July. Larvae feed on buckwheat (Eriogonum spp.).

Arrowhead Blue, Glaucopsyche piasus . (Plate 7.4) The underside of the wing bears white "arrowhead" markings. The adults occur in June at 9,000–11,000 ft (2,700–3,400 m). Larvae feed on lupine (Lupinus spp.).

Silvery Blue, Glaucopsyche lygdamus . (Plate 7.4) The underside of the wing bears a single jagged row of small black dots ringed with white. The adults occur in May between 6,000 and 10,000 ft (1,800 and 3,000 m). Larvae feed on lupine (Lupinus ), and locoweed (e.g., Oxytropis and Astragalus ).

Spring Azure, Celastrina ladon . (Plate 7.4) Occurs from 5,000 to 10,000 ft (1,500 to 3,100 m) during the spring and summer.

Pygmy Blue, Brephidium exilis . (Plate 7.4) Small, with a wingspread less than 3/4 in (1.9 cm). Occurs between 4,000 and 11,000 ft (1,200 and 3,400 m) from spring to fall. Larvae feed on pigweed (Chenopodium spp. and Amaranthus spp.) and saltbush (Atriplex spp.).

Blue Copper, Lycaena (Chalceria) heteronea . (Plate 7.4) Occurs from 10,000 to 12,000 ft (3,100 to 3,700 m) during the summer. Larvae feed on buckwheat (Eriogonum spp.).

Edith's Copper, Lycaena (Gaeides) editha . (Plate 7.4) Occurs from 10,000 to 13,000 ft (3,100 to 4,000 m) during the summer. Larval food plants are unknown.

Cupreus Copper, Lycaena cuprea . (Plate 7.4) Occurs from 10,000 to 13,000 ft (3,100 to 4,000 m) during the summer and fall. Larvae feed on Mountain Sorrel (Oxyria ).

Thicket Hairstreak, Mitoura spinetorum . (Plate 7.4) A species with short "tails" on the hindwings. Wings have dull blue upper surfaces and brown lower surfaces. It occurs from 6,000 to 9,000 ft (1,800 to 2,700 m) during the summer. Larvae are known to feed on mistletoe (Arceuthobium ) species that parasitize conifers.

Siva Hairstreak, Mitoura siva . (Plate 7.4) Has "tails" like M. spinetorum , but wings have brown upper surfaces and greenish lower surfaces. Ir occurs from 6,000 to 8,000 ft (1,800 to 2,400 m) during the spring. Larvae resemble the twigs of their host plant, juniper (Juniperus spp.).

Comstock's Green Hairstreak, Callophrys comstocki . A tailless hairstreak light grey above with a broken white band on the underside of the hindwing, edged inwardly with black. The undersurface of the wing is greenish. It occurs from 5,000 to 7,000 ft (1,500 to 2,100 m) in the spring. Larvae feed on buckwheat (Eriogonum ).

Brush-footed Butterflies (Family Nymphalidae). Nymphalids are commonly large and showy, and may be easily recognized by the presence of only four functional legs, the forelegs being modified into "drumming" organs used by the females to "taste" the host plants. Nymphalid caterpillars are commonly spiny or brightly colored, although the grass feeders tend to be green and difficult to see.

Monarch Butterfly, Danaus plexippus . (Plate 7.5) Occurs from 4,000 to 14,000 ft (1,200 to 4,300 m) from spring to fall. Larvae feed on milkweed (Asclepias spp.).

Dark Wood Nymph, Cercyonis oetus . (Plate 7.5) Occurs from 10,000 to 12,000 ft (3,100 to 3,700 m) in the summer. Larvae feed on grass.

Riding's Satyr, Neominois ridingsii . (Plate 7.1) Occurs from 9,000 to 11,000 ft (2,700 to 3,100 m). It "flushes" when disturbed, flies a short distance, and quickly alights, camouflaging itself on rocks or lichens. Its larvae probably feed on grass.

Neumoegen's Checkerspot, Chlosyne (Charidryas) neumoegeni . (Plate 7.5) Occurs from 4,000 to 6,000 ft (1,200 to 1,800 m) in the spring. Larvae feed on plants in the Sunflower Family (Asteraceae).

Leanira Checkerspot, Chlosyne (Thessalia) leanira alma . (Plate 7.5) Occurs from 5,000 to 8,000 ft (1,500 to 2,400 m) in the spring. Larvae feed on Indian Paintbrush (Castelleja spp.).

Anicia Checkerspot, Euphydryas (Occidryas) anicia wheeleri . (Plate 7.5) Occurs from 9,000 to 11,000 ft (2,700 to 3,400 m) in summer. Larvae feed on plants in the Scrophulariaceae, including species of Penstemon and Castelleja .

Milbert's Tortoiseshell, Nymphalis (Aglais) milberti . (Plate 7.5) Occurs from 10,000 to 13,000 ft (3,100 to 4,000 m) in the summer and fall. Larvae usually feed on nettles (Urtica spp.) but have been reported on species of willow (Salix spp.) and sunflower (Helianthus spp.).

Mourning Cloak, Nymphalis antiopa . (Plate 7.1) A large, easily recognized species that occurs along streams and in the Owens Valley. The larvae feed on willow (Salix spp.) and other trees.

Painted Lady, Vanessa cardui . (Plate 7.5) Occurs from 4,000 to 14,000 ft (1,200 to 4,300 m), spring to fall. Larvae feed on plants in the Sunflower Family (Asteraceae).

West Coast Lady, Vanessa annabella . (Plate 7.5) Adults occur in June near 7,000 ft (2,100 m). Larvae feed on plants in the Mallow Family (Malvaceae).

Red Admiral, Vanessa atalanta . (Plate 7.1) Occurs from 4,000 to 11,000 ft (1,200 to 3,400 m), spring to fall. This large species feeds on nettle (Urtica spp.).

Lorquin's Admiral, Limenitis lorquini . (Plate 7.1) Larvae feed on willow, poplar, and other trees along streams and in the Owens Valley. The adults fly with quick wingbeats interspersed with gliding and are large and striking.

Flies, Gnats, and Mosquitoes (Order Diptera)

Dipterans, also known as the "true flies," may be recognized by the possession of only two wings instead of the four that other adult insects have. In Diptera, the hindwings have been modified into tiny, clublike halteres, which are used as organs of balance. Most dipterans lack mandibles, and adults are common visitors to flowers, where they drink nectar with their spongelike or sucking mouthparts. Adult female dipterans of many species are blood suckers and require one or more blood meals for egg production. The larvae of many dipterans are aquatic or feed in anaerobic decaying matter; others feed on plant material or are predaceous on other insects. One family (Tachinidae) is particularly important as parasites of caterpillars; the larvae feed internally until the entire host is consumed. Dipteran larvae are legless and maggotlike except for specialized aquatic forms, such as mosquito larvae.

Crane flies,Tipulaspp. (Family Tipulidae). (Fig. 7.25) Crane flies have the appearance of very large mosquitoes but are completely harmless. They occur at elevations up to 13,000 ft (4,000 m).

Mosquitoes,Anophelesspp. (Family Culicidae). (Fig. 7.26) Mosquitoes are common in wet areas, such as along the Owens River or boggy areas at higher elevations. Members of this genus are the principal vectors of malaria in California.

Robber Flies, (Family Asilidae). (Fig. 7.27) Robber Flies are common and easily recognized by their stout thorax, wings, and legs, and by their behavior of perching in exposed positions and sallying forth after flying prey. They are very diverse in the White Mountains at all elevations.

Figure 7.25

Crane Fly (Tipula sp.).

Figure 7.26

Mosquito (Anopheles sp.).

Figure 7.27

Robber Fly.

Hover Flies (Family Syrphidae). Hover Flies are commonly seen visiting flowers. Many species look very much like bees or wasps. They also commonly hover in midair, holding a fixed position relative to the surrounding vegetation, and abruptly changing position when approached. Larvae of some species are caterpillarlike and feed on aphids and small herbivorous insects. Some species occur at elevations as high as the top of White Mountain Peak.

Common Hover Fly, Metasyrphus aberrantis . (Plate 7.1) Occurs on flowers from 6,000 to 10,000 ft (1,800 to 3,100 m). The larvae crawl on plants and eat aphids and other small insects. They are legless, yet manage to cling to vegetation very efficiently.

Sawflies, Wasps, Bees, and Ants (Order Hymenoptera)

Adult hymenopterans possess four wings, with the hindwings smaller than the forewings. Except for the Sawflies, hymenopterans also have a constricted "waist" between the first and second abdominal segments and, in females, an ovipositor modified into a stinger. The larvae of Sawflies are mainly herbivorous and greatly resemble lepidopteran caterpillars. The wasps are mainly predaceous or parasitic on other insects and are very important in controlling their numbers. Some wasps and Sawflies parasitize plants by laying their eggs in plant tissues. The egg or resulting larvae then induces the plant to form a gall, which surrounds the insect. These galls are particularly common on oaks and willows. The bees feed primarily on pollen and nectar and are probably the most important agents of flower pollination.

Many hymenopterans live in tightly coordinated social groups usually dominated by one or more reproductive "queens." The queen's efforts at reproduction are aided by numerous "workers," which may be temporarily or permanently sterile. Ants represent the extreme of this type of social evolution, and the sterile, wingless workers are among the most common, visible insects in many habitats. They feed on small insects and obtain sugary "honeydew" secretions from Homoptera. They are very important in controlling the numbers of other insects in many habitats.

Sawflies,Tenthredospp. (Family Tenthredinidae). (Fig. 7.28) Adult Sawflies resemble wasps, except that they have a stout "waist" instead of the threadlike waist of the true wasps and bees. Sawflies are commonly encountered as larvae feeding on the leaves of plants. Many Sawfly larvae look very much like caterpillars of Lepidoptera,

Figure 7.28

Sawfly (Tenthredo sp.).

Figure 7.29

Ichneumon (Ophion sp.).

except that they possess prolegs on every abdominal segment rather than on five or fewer segments (as seen in Lepidoptera). Many Sawflies lay their eggs internally in the host plant leaves rather than externally, as in most Lepidoptera. Some Sawflies make galls in their host plants. Sawflies occur as high as Crooked Creek in the White Mountains (10,150 ft, 3,100 m).

Ichneumons,Ophionspp. (Family Ichneumonidae). (Fig. 7.29) Ichneumons are elongated wasps, the larvae of which are parasitic on other insects. They are frequently seen searching vegetation for their hosts by quivering their long, curled antennae and making short flights between branches or plants. They occur at all elevations below 13,000 ft (4,000 m).

Cuckoo Wasps,Chrysisspp. (Family Chrysididae). Cuckoo Wasps are brillant green and reproduce by parasitizing larvae of other wasps in their burrows. They occur at all elevations below 13,000 ft (4,000 m), where they may be seen drinking from flowers.

Tarantula Hawks,Pepsisspp. (Family Pompilidae). (Plate 7.1) Easily recognized wasps because of their very large size and black and orange wings, they occur from 4,000 to 8,000 ft (1,200 to 2,400 m) in summer and fall. These and other spider wasps actively hunt spiders, which they paralyze by stinging and drag to a burrow. Then they deposit an egg and seal up the burrow. Eventually the egg hatches, and the wasp larva consumes the spider. Smaller spider wasps in the same family occur at elevations up to 13,000 ft (4,000 m).

Resin Bees,Dianthidiumspp. (Family Megachilidae). (Fig. 7.30) Occur at elevations below 8,000 ft (2,400 m), and possibly higher. Commonly found in deserts and foothills in California, they nest alone rather than in colonies. Resin Bees are common pollinators of Phacelia and other desert flowers.

Figure 7.30

Resin Bee (Anthidium sp.).

Figure 7.31

Honey Bee (Apis mellifera ).

Bumble Bees,Bombus centralisandB. morrisoni(Family Apidae). (Plate 7.1) Bumble bees occur at elevations up to 11,000 ft (3,400 m). Commonly seen visiting flowers, these bees live in nests underground.

Honey Bee,Apis mellifera(Family Apidae). (Fig. 7.31) Abundant at lower elevations, an introduced bee that has established itself in the wild, nesting in hollows in trees, caves, and underground.

Carpenter Bee,Xylocopa californica arizonensis(Family Anthophoridae). (Fig. 7.32) Adults are large, black bees that bore into dead wood to make nest chambers. They occur between 6,000 and 8,000 ft (1,800 and 2,400 m).

Ants (Family Formicidae). Ants are familiar organisms at all elevations in the White Mountains. Protected underground and by numerous worker individuals willing to sacrifice their lives in defense of the colony, ants are among the most successful creatures on earth. Perhaps because of the ants' abundance, many insects have evolved specific adaptations to survive with them. For example, aphids and many butterflies of the Family Lycaenidae secrete sugary honeydew, which attracts ants, which in return protect the insects from enemies such as parasitic wasps and Ladybird Beetles.

Figure 7.32

Carpenter Bee (Xylocopa sp.).

Figure 7.33

Mound Ant (Formica sp.).

Figure 7.34

Carpenter Ant (Camponotus sp.).

Mound Ants, Formica spp. (Fig. 7.33) Occur from the Owens Valley to 12,500 ft (3,800 m) in large, mound-shaped nests on bare ground. These ants may be very aggressive. The species F. subpolita occurs at Barcroft Laboratory at 12,500 ft (3,800 m).

Carpenter ants, Camponotus spp. (Fig. 7.34) Large, black ants that usually nest in or near dead wood, which they hollow out. In spite of their large size, these ants are commonly timid and nonaggressive. They occur in dead wood to 11,000 ft (3,400 m). C. sansabeanus and C. ochreatus nest in dry wood near Westgard Pass.

References

Borror, D. J., D. Delong, and C. A. Triplehorn. 1976. Introduction to the Study of Insects . Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, New York.

Borror, D. J., and R. E. White. 1970. A Field Guide to the Insects of America North of Mexico . Peterson Field Guide Series, Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Emmel, T. C., and J. F. Emmel. 1973. The Butterflies of Southern California . Natural History Museum, Los Angeles.

Garth, J. S., and J. W. Tilden. 1986. California Butterflies . University of California Press, Berkeley.

Powell, J. A., and C. L. Hogue. 1979. California Insects . University of California Press, Berkeley.

8—

Fishes

Edwin P. Pister

Introduction

For all practical purposes, the fishes of the White Mountains are introduced species. It is unlikely that native species ever existed in these mountains except in the very lowest reaches of either easterly or westerly drainages.

Perhaps the terms introduced species and native species should be clarified. When Europeans first arrived in the Owens Valley, only four fishes were found there, all of them considered nongame species: the Owens Pupfish (Cyprinodon radiosus Miller), Owens Chub (Gila bicolor snyderi Miller), Owens Dace (Rhinichthys osculus sp.), and Owens Sucker (Catostomus fumeiventris Miller). On the east side of the range, in Fish Lake Valley, only a chub (Gila sp.) was found. These constitute the native fish fauna of the White Mountains area, and through many years of neglect only one of them, the Owens Sucker, now occurs in abundance. The others are endangered, threatened, or of undetermined status. Recovery programs are in progress for the endangered and threatened fauna, under the provisions of the federal and state endangered species acts.

The streams flowing from the White Mountains are spring-fed. Being a desert range, the White Mountains seldom hold the summer snowbanks that typify the Sierra Nevada, just a few miles to the west. Once the winter snows have melted, the stream flows quickly stabilize except during occasional summer thundershowers.

A glance at a map of the Inyo National Forest reveals a large number of streams flowing from the crest of the White Mountains. However, only a few of them contain significant fish populations, and these generally only in the upper reaches. The vast majority of these streams, whether they flow east or west, have for many years been diverted for irrigation.

Early Trout Planting

The exact history of fish introductions into the White Mountains is unknown. Accurate records of early fish planting, unfortunately, were not kept. It is safe to assume, however, that most introductions occurred in this century prior to World War II. Some introductions were made by the California Division (now Department) of Fish and Game, and others were made by the Rainbow Club, an early sportsmen's club headquartered in Bishop. The club has planted no fish since before World War II.

Most White Mountain streams have been planted with trout, and one may expect to find Eastern Brook Trout, Salvelinus fontinalis (Mitchill), and Rainbow Trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdnerii (Richardson), in the higher elevations and Brown Trout,

Salmo trutta Linnaeus, in the lower elevations. However, the California streams are no longer being stocked with trout; all populations are self-sustaining. The Nevada Department of Wildlife, however, occasionally stocks Rainbow Trout in streams flowing into northern Fish Lake Valley.

Paiute Trout

An exception to the general rule concerning trout species composition and distribution is found in Cottonwood Creek, which flows easterly into Fish Lake Valley from near White Mountain Peak. In 1946, when Department of Fish and Game and U.S. Forest Service biologists noted that the Paiute Cutthroat Trout, Oncorhynchus clarki seleniris (Snyder), populations of the upper East Fork Carson River (Alpine County, California) were seriously threatened, a limited number were planted in the previously fishless upper North Fork Cottonwood Creek. This stream has been generally closed to angling since that time. The subspecies is currently listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act.

The North Fork Cottonwood Creek Paiute Cutthroat population is perhaps the only genetically pure population left in the world, and it is being protected as part of the recovery plan for the subspecies. Should the subspecies recover sufficiently, management plans may allow a very limited harvest. Until that time, however, the North Fork Cottonwood Creek will remain closed to angling. To accelerate the recovery of the Paiute Cutthroat Trout, it may be spread to other suitable streams as part of a plan under consideration by the Department of Fish and Game and the U.S. Forest Service. At present, however, the only stream area in the White Mountains with a special restriction is the North Fork Cottonwood Creek. Anglers planning to fish anywhere in California should check current fishing regulations, which are available at most sporting goods stores.

Species Descriptions

Rainbow Trout,Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdneri(Richardson). (Fig. 8.1) Other than the Paiute Trout, the Rainbow Trout is the only trout species in the White Mountains that is native to California. It may be distinguished from the other species by its generally silvery appearance and profusion of spots, including a spotted tail. It also commonly has a reddish lateral band extending from head to tail. However, look for the spotted tail as the definitive characteristic. None of the other trout species in the White Mountains has a heavily spotted tail.

Eastern Brook Trout,Salvelinus fontinalis(Mitchill). (Fig. 8.2) Although called a trout, the Eastern Brook Trout is actually a char. It is native to the eastern United States and was brought to California many years ago. It has been introduced widely throughout the Sierra Nevada and occurs in several streams in the White Mountains.

Eastern Brook Trout are generally olive green with light spots on the sides. They may be distinguished from the trout species by vermiculations, or wavy lines, along

Figure 8.1

Rainbow Trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdnerii (Richardson).

Figure 8.2

Eastern Brook Trout, Salvelinus fontinalis (Mitchill).

Figure 8.3

Paiute Cutthroat Trout, Oncorhynchus clarki seleniris

(Snyder).

Figure 8.4

Brown Trout, Salmo trutta Linnaeus.

the back from head to tail. They also have distinct white borders along the anterior margins of the ventral and anal fins.

Paiute Cutthroat Trout,Oncorhynchus clarki seleniris(Snyder). (Fig. 8.3) The Paiute Cutthroat Trout, which is native to the Great Basin, was introduced into the North Fork Cottonwood Creek in 1946 in one of the first recorded efforts toward species preservation in California. It has survived in Cottonwood Creek in limited numbers, but the North Fork is closed to angling to ensure its protection. The Paiute Cutthroat Trout evolved through geographic isolation from the Lahontan Cutthroat Trout, Oncorhynchus clarki henshawi (Gill and Jordan), in upper Silver King Creek, Alpine County.

This trout normally has an overall purplish hue, which distinguishes it from the other trout species in the White Mountains. It also has very few (if any) spots and possesses the distinctive reddish cutthroat marks under the jaw.

Brown Trout,Salmo truttaLinnaeus. (Fig. 8.4) The Brown Trout, a native of Europe, was brought into California many years ago and eventually found its way into the White Mountains. It is common there, especially in the lower stream areas. It is an excellent game fish and is sought after by anglers, especially fly fishermen.

The Brown Trout is usually dark or olive brown on the back and golden brown on the sides. It generally has red spots surrounded by a halo on its sides. It may have spots on the tail, but they are sparse in contrast to the profusion of tail spotting present in Rainbow Trout.

Conclusion

Some researchers are now questioning the general advisability of introducing nonnative species into a naturally balanced ecosystem. The trout stocking that occurred in the early 1900s was a result of resource management procedures in practice at that time, but current research is beginning to recognize the long-term implications of stocking to the ecosystem. Such introduction invariably harms native organisms and is now considered unacceptable ecological practice.

References

California Department of Fish and Game. 1969. Trout of California . Calif. Dept. of Fish and Game, Sacramento.

Hubbs, C. L., and R. R. Miller. 1948. Correlation between fish distribution and hydrographic history in the desert basins of western United States. In The Great Basin, with emphasis on glacial and postglacial times . Bulletin of the University of Utah, no. 38, pp. 17–166.

Miller, R. R. 1948. The cyprinodont fishes of the Death Valley system of eastern California and southwestern Nevada . Miscellaneous Publications of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, no. 68.

Miller, R. R. 1973. Two new fishes , Gila bicolor snyderi and Catostomus fumeiventris, from the Owens River basin, California . Occasional Papers, Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, no. 667.

Miller, R. R., and E. P. Pister. 1971. Management of the Owens pupfish, Cyprinodon radiosus , in Mono County, California. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 100:502–509.

Pister, E. P. 1974. Desert fishes and their habitats. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 103:531–540.

Pister, E. P. 1976. A rationale for the management of nongame fish and wildlife. Fisheries 1:11–14.

Pister, E. P. 1979. Endangered species: Costs and benefits. Environmental Ethics 1:341–352.

Pister, E. P. 1981. The conservation of desert fishes. In R. J. Naiman and D. L. Soltz (eds.). Fishes in North American deserts , pp. 411–455. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Schumacher, Genny (ed.). 1969. Deepest valley: Guide to Owens Valley and its mountain lakes, roadsides, and trails . Wilderness Press, Berkeley, Calif.

Soltz, D. L., and R. J. Naiman. 1978. The natural history of native fishes in the Death Valley system . Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Science Series, no. 30.

Vestal, E. H. 1947. A new transplant of the Paiute trout (Salmo clarkii seleuiris ) from Silver King Creek, Alpine County, California. California Fish and Game 33(2):89–95.

9—

Amphibians

J. Robert Macey and Theodore J. Papenfuss

Introduction

Amphibians are cold-blooded vertebrates with moist, scaleless skin. These animals either occur in close association with permanent water or are active only during wet times of the year. There are approximately 3,200 species in the world, and amphibians are present on all continents except Antarctica.

Amphibians are divided into three groups: caecilians, salamanders, and frogs and toads. Caecilians are elongate, "wormlike," burrowing or aquatic forms that lack limbs and functional eyes. The approximately 165 species are restricted to the tropical regions of the world; no species occur in the United States. Most caecilians are less than 2 ft (0.6m) long; however, one species in South America reaches a length of 5 ft (1.5m).

Most salamanders have a lizardlike shape with four legs and a tail. They have smooth, moist skin that lacks scales. In the New World there are three areas with high species diversity. One is the mountainous region of southern Mexico and northern Central America, with some 50 species. Another is the Appalachian Mountains of the eastern United States, with about 45 species. The third region comprises the Pacific states of California, Oregon, and Washington, with about 35 species.

The species that are present in California have two very different developmental patterns. Some breed in water, and the adults return to streams and ponds during the rainy season to lay eggs. Gilled larvae develop in the water and later transform into terrestrial adult salamanders. Other salamanders are completely terrestrial. The eggs are laid on land in moist places. The larval stage takes place in the egg, and small, fully transformed salamanders emerge. All western fully terrestrial salamanders lack lungs, and respiration takes place through the skin.

Three species of salamanders are known to occur in the California portion of the White-Inyo mountains region. The only state with no native salamanders is Nevada. There have been several reports of salamanders in Nevada, but none have been confirmed. Although the species accounts included here for salamanders have been brought up to date, they are probably incomplete and may even be lacking a species. We would appreciate receiving any additional information, such as a new distribution or a salamander that does not fit the descriptions.

The frogs and toads are the largest group of amphibians. Approximately 2,600 species of frogs and toads are known, and they occur on every continent except Antarctica. The greatest species diversity is in the tropics, but frogs and toads are

Map 9.1

Map 9.2

well represented in temperate regions. These amphibians occur in a great variety of habitats. Some species occur in arid regions, where they spend most of their lives underground, coming to the surface only during occasional rains. Others are fully aquatic and never leave the water. A few species in tropical regions spend their entire lives in the tree canopy. There are 23 families of frogs and toads worldwide, of which 5 occur in California and Nevada. The families that occur in the area under study are the True Toads (Family Bufonidae), Treefrogs (Hylidae), Spadefoot Toads (Pelobatidae), and True Frogs (Ranidae).

Species Accounts

The following species accounts cover the three salamanders and seven frogs and toads that occur in the White-Inyo mountains region. Accounts are ordered by main group, then alphabetically by family name, and finally alphabetically by species name. Each account consists of a brief identification, information on habitat, and a remarks section, which treats natural history. A brief summary of the range and a list of the exact localities corresponding to the dots on the range maps are also included. When the locality is vague, it is not plotted on a map. In these lists the first reference to a place name is listed in its entirety, and all other references to that place name follow it as separate localities. These localities are based on museum specimens. The majority of specimens from this region are deposited in the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California at Berkeley (MVZ). Other museums represented in the localities sections are: American Museum of Natural History, New York (AMNH); California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco (CAS); Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh (CMNH); Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago (FMNH); University of Kansas (KU); Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (LACM); Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University (MCZ); San Diego Natural History Museum (SDSNH); University of Michigan Museum of Zoology (UMMZ); University of Nevada, Reno (UN); and United States National Museum, Washington, D.C. (USNM). The acronym of the museum follows each locality. Absence of an acronym indicates that the locality is based on a specimen from the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. For accuracy, elevations and distances of localities are cited as recorded by the collector and have not been converted to or from the English or metric system.

The color plates of species will aid in identification. All amphibians in the color plates are from the White-Inyo mountains region except the Northern Leopard Frog (Rana pipiens ), which is from Churchill County, Nevada. For each species, pertinent literature references are listed; the complete citations are at the end of the chapter. General references to the amphibians of the region are: Macey (1986), Papenfuss (1986), Stebbins (1951), and Stebbins (1985). All scientific names are after Collins (1990). In addition, the following chapter of this book, on reptiles, has two sections that contain general information on amphibians of the White-Inyo mountains region.

Lungless Salamanders (Family Plethodontidae)

Kern Plateau Slender Salamander, Batrachosepssp.(no author, not yet described). (Plate 9.1) 3–4 in (7.5–10 cm); dorsal pattern variable; black with a brown middorsal stripe or black with an overlay of silver specks; only four toes on each foot. Habitat: This species occurs around permanent springs and creeks with riparian vegetation. The salamanders live in the daytime under cover objects such as rocks and logs. Remarks: This salamander is related to the Inyo Mountains Slender Salamander (B. campi ) and was the second salamander to be discovered in the White-Inyo mountains region. The Kern Plateau Slender Salamander has a narrower head and shorter legs than the Inyo Mountains Slender Salamander. The ranges of the two species do not overlap. Species of the genus Batrachoseps are the only salamanders in California that have just four toes on each hind foot. Other species of Batrachoseps , known as Slender Salamanders, are widely distributed throughout California. They commonly occur in urban areas under rocks and boards. This species is currently known from the Kern Plateau and the southeastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada, but it may have a more extensive range. Range: Kern Plateau and the eastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada south and west of Owens Lake. Reference: Stebbins (1985).

Inyo Mountains Slender Salamander,Batrachoseps campi(Marlow, Brode & Wake, 1979). (Plates 9.2 [from Hunter Canyon] and 9.3 [from French Spring], Map 9.3) 2–3 in (5–7.5 cm); dorsal pattern variable; background color dark brown to black; in some populations scattered green, lichenlike spots on body; in others the background color is completely overlain with silver flecks; only four toes on each foot. Habitat: Occurs only around permanent springs and seeps that provide a riparian habitat. Inyo Mountains Slender Salamanders are active at night. During the day they take shelter under moist rocks or in damp crevices. They have been found at springs as low as 1,800 ft (550 m) and as high as 8,600 ft (2,600 m). Remarks: The discovery in 1973 of these salamanders in the arid Inyo Mountains was unexpected. In the past, numerous biologists had visited many of the springs where these salamanders live without detecting them, because salamanders are not considered desert animals. Doubtless, additional populations will be found. These salamanders are relicts that entered the Inyo Mountains prior to the rise of the Sierra Nevada and the formation of the Mojave and Great Basin deserts. In some instances these isolated populations may consist of only a few hundred individuals. They are protected by state law and should not be collected. At the present time, capping of springs is the major threat to these populations. Range: Both east and west slopes of the Inyo Mountains. References: Marlow, Brode, and Wake (1979); Yanev and Wake (1981).

Localities: California, Inyo Co.: 6,800–7,000, 8,000–8,300 ft, Addie Canyon; 6,400 ft, Barrel Springs; 6,400 ft, Cove Springs; 3,500 ft, Craig Canyon; 6,000 ft, French Spring (LACM, MVZ); 1,800 ft, 2,200 ft, Hunter Canyon; 4,000 ft, Keynot Canyon; 6,500 ft, Lead Canyon (LACM, MVZ); 5,600 ft, Long John Canyon (LACM, MVZ); 3,500 ft, McElvey Canyon; 7,500 ft, top of ridge between Lead and Addie canyons; 7,200 ft, Waucoba Canyon; 4,700 ft, Willow Creek Canyon.

Map 9.3

Map 9.4

Owens Valley Web-toed Salamander, Hydromantessp. (no author, not yet described). (Plate 9.4) 3 1/2–4 1/2 in (9–11.5 cm); body and head very flattened; dorsal pattern variable; greenish brown to silver with scattered black spots; scattered lichenlike silver spots on ventral surface; feet with extensive webbing; four toes on front feet and five toes on hind feet. Habitat: The Owens Valley Web-toed Salamander occurs in the vicinity of permanent springs and mountain streams with riparian vegetation. Although this salamander is nocturnal, it can be encountered under wood and rocks in areas with moist soil. Remarks: The Genus Hydromantes is distributed in California, Italy, and Sardinia. The species in Europe are the only members of the lungless salamander family, Plethodontidae, in the Old World. The Owens Valley Web-toed Salamander was discovered in 1985 during field work in preparation for this chapter.

Range: Eastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada, at least from the area around Owens Lake to Big Pine. Reference: Wake, Maxson, and Wurst (1978).

True Toads (Family Bufonidae)

Western Toad,Bufo boreas(Baird & Girard, 1852). (Plate 9.5, Map 9.4) 3–5 1/2 in (7.5–13.75 cm); marbled dorsal pattern of brown, gray, and green in equal proportions; distinct white or light yellow line down middle of back; ventral background color cream with black spots; small warts scattered over back; oblong gland (parotoid gland) behind eye is longer than upper eyelid. Habitat: In White-Inyo Range, occurs around permanent ponds and slow-moving streams. Western Toads are generally nocturnal; however, recently discovered populations in the northern White Mountains (see Map 9.4) are also active during the day, at least in spring and summer. Remarks: Western Toads are a common, wide-ranging species in much of the western United States, occurring from sea level to above 9,000 ft (2,740 m). They are often seen at night on roads and in yards in rural areas. In the White-Inyo mountains region, this species is generally restricted to valleys, but it has been found above 7,000 ft (2,130 m) in the Pinyon-juniper Woodland of the northern White Mountains. A Creosote Bush Scrub outpost for this species is Darwin Falls Canyon in the northern Argus Mountains. Here the Western Toad and the Red-spotted Toad (B. punctatus ) coexist and occasionally hybridize (see Red-spotted Toad account). At a second isolated locality, Fish Lake in Fish Lake Valley, Western Toads may be extinct due to the introduction of Bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana ) (see Bullfrog account). Range: Darwin Falls Canyon, northern Argus Mountains; Owens Valley; vicinity of Fish Lake, Fish Lake Valley; extreme northern White Mountains. Reference: Karlstrom (1962).

Localities: California, Inyo Co.: Alvord (USNM); 3.0 mi S Bartlet; Batchelder Spring, Westgard Pass; Big Pine; 1.5 mi SW; 4 mi NW (JACM); Bishop; 0.5 mi NW (UMMZ); 5 mi E (LACM); 4000 ft, Bishop Creek (USNM); Darwin Falls, Argus Mtns.; Diaz Lake, Owens Valley (CAS); Fish Lake Spring (CAS); Independence; Laws (CAS, MVZ); near (UMNZ); Lone Pine (MCZ, MVZ, USNM); 2.9 mi S (CAS). Mono Co.: Benton; 5 mi N (SDSNH); 3 mi from Nevada State line, spring, Taylor Ranch, 5 mi N Benton (UMMZ). Nevada, Esmeralda Co.: Fish Lake (MVZ, UMMZ); 7,820 ft, Buffalo Canyon. Mineral Co.: Orchard Spring, Buffalo Canyon; Queen Canyon.

Black Toad,Bufo exsul(Myers, 1942). (Plate 9.6, Map 9.5) 1 1/2–2 1/2 in (3.75–6.25 cm); dorsal color predominantly black; faint white line down middle of back; ventral color black, with white mottling becoming more extensive on chin; small warts scattered over back; oblong gland (parotoid gland) behind eye is longer than upper eyelid. Habitat: This species is the most aquatic toad in the region. It never occurs far from permanent water. Black Toads prefer marshy areas around pools or slow-moving streams. They are generally diurnal but may be active at night during the summer. Remarks: The Black Toad along with the three salamanders are the only amphibians endemic to the White-Inyo mountains region. It is native only to the Deep Springs Valley but has been introduced to Batchelder Spring on the west side of

Map 9.5

Map 9.6

Westgard Pass. However, no toads have been seen at Batchelder Spring in recent years, and that population may be extinct. The Black Toad is closely related to the Western Toad (B. boreas ). It has been isolated from the Western Toad for at least 12,000 years, since the last Pleistocene moist period. The Black Toad, and the Amargosa Toad (B. nelsoni ) in Nye County, Nevada, have commonly been regarded as subspecies of the Western Toad. However, a recent genetic study suggests that these two forms be recognized as full species. The only other amphibian in Deep Springs Valley is the Great Basin Spadefoot (Spea intermontana ). Spadefoots have light-colored, smooth skin and spades on the hind feet (see Great Basin Spadefoot Toad account). Black Toads are protected by California law and should not be collected. Range: Areas of permanent