Body Garments

Breechclout.

—The breechclout is the only undergarment worn by the men, both in everyday life and in ceremonies. It is used to protect the person even when trousers are worn. It is always worn under the dance kilt except by the Mudheads, the Zuñi clowns, who are "just like children"[22] and are symbolized in myth as supernaturals "in semblance of males, yet like boys, the fruit of sex ... not in them."[23]

The size of the breechclout varies. In Taos it is broad and long, hanging

nearly to the ground,[24] while in the west it is short and narrow, the ends merely folding over the belt, front and back. The most desired material for this garment is hand-woven cotton cloth, but dark blue native cloth is often used, and sometimes even the woven ceremonial sash itself is used, its gay-hued ends contributing greatly to the color of figure and dance.[25]

The ordinary breechclout often has fringed ends or ends finished with embroidery or bright cording in geometric patterns. Decorated ends form a design element in the costume when drawn out over the belt and allowed to hang free (pl. 35).

Kilt.

—The most characteristic ceremonial garment is the kilt. The forms and materials for this garment are numerous, but most frequently the kilt is of white homespun cotton cloth in a plain basket weave. It is about fifty inches long and twenty inches wide; it is wrapped around the loins and held in place at the waist by a belt. Generally made by the Hopi, the kilt is decorated by them with two embroidered panels symbolizing rain, clouds, and life—a characteristic design which always follows the same pattern, in black, green, and red.[26] Other pueblos often purchase from them kilt lengths of the white cloth and embroider or paint them in their own designs.

A band of black about an inch wide is often embroidered or crocheted around the bottom of the kilt, with small black squares or terraced shapes breaking into the white body at intervals above this lower border. The entire kilt is sometimes outlined with a thread of black, thus giving the garment definite limitations and forming a thin line of accent.

Special kilts of white cotton are painted or stained in the desired colors and designs. It has been suggested that this is the original method of decorating all white cotton garments.[27] The Hopi Snake Dance kilt is the most noticeable example today. On a background of tawny red a black band

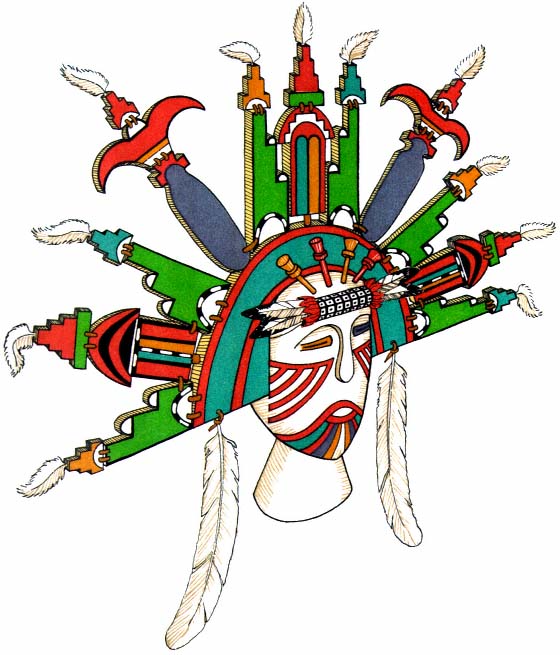

Plate 18.

Sio Shalako Maiden, Hopi. Mask of one of the giant

goddesses. The elaborate headdress of symbolic shapes is

held together by pegs and thongs. (Reconstructed from an

antique mask at the Laboratory of Anthropology, Santa Fe.)

with white borders zigzags through the center, "representing the plumed snake, the arrow-shaped marks representing the footprints of ducks and short parallel marks representing the footprints of the frog, both water animals."[28] This serpent band is continuous, with neither head nor tail. At the bottom of the kilt are two lines of color, yellow and blue, bordered by black and white interrupted lines. A fringe of metal cones, useful as noisemakers, finishes the lower edge.[29] Painted cotton kilts are used by the Rio Grande Pueblos for their Buffalo Dances. These were probably preceded by kilts of deerskin bearing a similar design. Native cloth kilts, dark blue or black, are often seen. They have a straight band of red and green through the center and are characteristic of the impersonators of the Mountain Sheep and other Rio Grande personifications (pl. 26).

Occasionally the Maiden's shoulder blanket is folded in the center and worn as a kilt, with the dark border at the lower edge.[30] These kilts are most frequently worn with the opening on the right side; occasionally the embroidered ones are adjusted so that the panel comes to the back to be covered by the fringe of the plaited sash. There is possibly a symbolic relationship between this fringe and panel.

One other cloth garment of this type should command attention. It is called the Salimapiya kilt because it is worn especially by impersonators of those gods.[31] As there are openings up each side, this kilt is apparently made of two pieces, a front and a back. The bottom has a wide, embroidered border similar to that of the great mantle but with characteristic medallions of colored butterflies and flowers (pls. 5, 6).[32]

The deerskin kilt, similar to the white cotton garment, is worn by dancers associated with the hunt or with war. The most primitive form is a simple, untrimmed skin, with trailing legs knotted up around the bottom. It appears to have been but half a hide cut longitudinally. The peg holes made when the hide was cured can be seen along the irregular edges.[33] The trimmed deerskin kilt, either white or stained with earth colors, is a garment of great luxury today because of the scarcity of wild animals. A

particular painted pattern found among the eastern pueblos has through the center a writhing black serpent (pl. 21) with a plumed head and a tapering tail.[34] This is the symbol for the mystical being who lives in the earth, for "who can know her secrets so intimately as a serpent who penetrates her bosom?"[35] The pictured reptile may be surrounded by various symbols: the cross of the road runner, or signs representing the sun, moon,

Figure 16.

Pattern of shirt made of dark hand-woven wool.

The sleeves are separate and sewed on the outside.

and stars. The lower edge is bordered in black and colored bands and around the ends of deerskin strips created by fringing the bottom are triangular tin pieces bent into cones. These replace the earlier animal-hoof and shell rattles with which these garments were formerly trimmed.

Special kilts are worn by certain dancers. One is fashioned of long horsehair stained red (pl. 35) and knotted on a cotton cord about the waist. It is held in place by a belt and hangs almost to the knee.[36] Another is made of long yucca leaves bound together on a single band, hanging straight and stiff in repose, but breaking and parting when the dancer is in motion.

Different materials or ornaments have been worn as overkilts. Narrow strips of cloth of a contrasting color, a fringe of leather, and a series of eagle feathers hung on deerskin thongs serve as examples.[37]

Shirt.

—"The typical body garment of the Hopi man in historic times was a length of dark blue or black woolen cloth with an opening made in the middle for drawing over the head, equal lengths of the garment hanging over the back and front like the Mexican poncho."[38] With the addition of sleeves, this garment makes a distinguishing feature of a costume, being worn on the outside either with or without a belt. It was made of three pieces of flat cloth, the two sleeves sewn to the poncholike piece at each side midway down the length. Each side and the lower sleeves from wrist to elbow were sewn together with a simple running stitch. This left an opening under each arm minus a gusset—a pattern never fully understood by the Pueblos. They never mastered the art of cutting and fitting, but depended upon cloth in the piece, either rectangular or square. They created all their garments on geometrical lines, in contrast to the tailored garments of the skin-clothed Plains Indian. This cloth shirt was probably the successor to the deerskin shirt of the Plains; the deerskin shirt is believed to have been universally worn by the Pueblos when animals were more plentiful.

Two special shirts were introduced by the Spaniards and can be seen today among the eastern pueblos. At Isleta a garment of fine stuff, fulled to a yoke and with gathered sleeves, has a small flat collar and tight cuff of white embroidered material edged with a thin strip of red. From San Juan have come a few examples of crocheted garments of white cotton string with fringes down the underarm and sides, copying in modern materials the age-old leather garment of the Plains warrior.

Women's dress.

—The ordinary dress of the Pueblo women is fashioned from a blanket of hand-woven woolen stuff which is dark brown, black, or blue. The brown and black are natural colors from the great number of brown and black sheep in the Indian flocks;[39] the blue was first obtained by dyeing the wool with indigo and later with aniline dyes.

This blanket is about four feet long and about three and one-half feet wide, a width sufficient to reach from the shoulder to the middle of the

lower leg. The weave is a twill in which use is made of the diagonal pattern for the body of the dress and a diamond pattern for the two borders, which are seven inches wide at top and bottom. These borders must both be completed before the center is begun, because of the complicated heddle setup required for the diamond weave. One border is finished and then the entire loom is inverted for the completion of the second border. Subsequently, the diagonal pattern is set up with a new heddle division and the weaving continues upward toward the first border.[40] The center section differs from the borders not only in weave, but often also in color; for instance, a black center may have dark blue borders, or a brown center may have black borders.

These blankets may be used as shawls and mantles as well as dresses. To fashion one into a dress, it is wrapped about the body and joined with red yarn part way up on the right side. The upper edges are drawn over the right shoulder and fastened there, leaving an opening for the right arm with the ends forming a kind of sleeve. The left arm and shoulder are bare and free. The break between the border and the center is often covered by cording or stitching of red and green yarn (pl. 19).

The Hopi men weave these blankets, which are in great demand among all the pueblos. In each village the inhabitants decorate the borders and sew the dresses in their own way. The Zuñi use a strong, embroidered border in dark blue. At Acoma, Tesuque, and Laguna red and green yarns have been introduced.

On rare occasions is seen a dark dress made of two pieces of cloth sewn up each side.[41] It is worn in the same manner as the one-piece dark dress. It is obvious that the smaller pieces of cloth would require a correspondingly small loom for the weaving.

In these native homespun woolen blanket dresses we see one of the last stands of the native culture. No matter how decadent and Americanized a village has become, it is still possible to find one of these original dresses

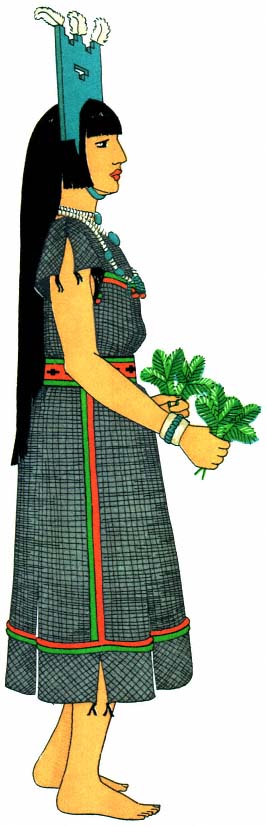

Plate 19.

Simple costume for women.

Tablita Dance, Santo Domingo.

on some old grandmother puttering about her daily work, or on some actor performing in a dance which has its roots deep in native custom.

There is a special white ceremonial dress (pl. 22). It is woven of cotton, a plain weave, and decorated with wide bands of colored embroidery at top and bottom. So is the white mantle. The two garments are often interchangeable, although there is supposed to be an appreciable difference in size. The mantle originated from the great white robe and the dress from the smaller robe, both of which were woven for each Hopi bride at the time of her marriage. Today there are worn under these dresses other dresses of manufactured cloth with long sleeves and high necklines and trimmed with lace and fancy braid. The impersonators of female characters have sometimes taken over this added garment, as in the Kokochi ceremony at Zuñi.

Trousers.

—During the period of Spanish settlement and influence, a kind of trousers became a part of the men's everyday dress. Its origin is uncertain. It could have come with the colonists from Spain by way of Mexico and it could have developed from the hip-length leggings made of animal skin. In any event, there appeared loose white cotton trousers, of about ankle length, made of two straight pieces of material seamed on the outside of the leg. These trousers were gathered on a cord about the waist, the top was concealed under the long tails of the shirt, and the breechclout protected the opening. A slit from the bottom almost to the knee was made on the outside of each leg.[42] Similar hip-length leggings of skin and colored flannel are found among the Rio Grande Pueblos. At Taos today, by a ruling of their council of governors, a man is not permitted to wear modern trousers.[43] As a compromise, the seat is removed and the breechclout substituted.

Trousers are not often worn in the ceremonial dances. One may, however, see them on members of the choir, the standard bearer, those who impersonate hunters, and a few supernaturals (for example, the Nataka men, pl. 33).