Akrivie Phrangopoulo

Naxos

The Cyclades[1] are one of the places in the world that most truly deserve the epithet "seductive," though many of them can quite rightly be called barren rocks. But on the bosom of these Grecian seas, where the hands of the gods have strewn them, these rocks sparkle like so many precious stones. The light that floods them in the midst of a flawless sky, and the azure seas in which they are set, turn them according to the time of the day into so many amethysts, sapphires, rubies, topazes. In reality, they are sterile, poor, rather barren, certainly melancholy, but these faults disappear under an incomparable majesty and grace. The Cyclades remind one of very great ladies born and raised in the midst of wealth and elegance. None of the lavishness of the most refined luxury was unknown to them. But misfortune struck them, great and noble misfortune; they withdrew from the world with the remnants of their wealth; they no longer pay visits, they do not receive anyone; nevertheless, they are still great ladies, and from the past they retain a sort of supreme refinement forbidden to the parvenu, a charming serenity and an adorable smile.

A few years ago the English corvette Aurora ,[2] coming from Corfu under sail in accordance with the prudent regu-

lations of an Admiralty miserly with its coal, happened one morning shortly before daybreak to be at the very center of the archipelago in question. The captain, Henry Fitzallan Norton, was asleep in his berth when a quartermaster dispatched by the navigating officer woke him up.

"Sir! Sir! . . ."

At the sound of this familiar voice, the captain had opened his eyes and answered:

"What is it?

— Sir, Naxos is in sight.

— All right," Norton answered; and since he had played whist rather late in the wardroom, he turned over in his bunk meaning to go back to sleep, which he was not permitted to do. Something black and hairy slowly rose up from the edge of the bunk, the noise of a prolonged yawning was heard, and while a huge tongue advanced toward his chin with the obvious desire to cover it with its pink expanse, eyes as intelligent as a dog's eyes can be were looking into his and saying:

"For Heaven's sake, wake up; I've slept enough.

— Well, since I must, the captain answered, I'm getting up, Dido, I'm getting up!"

And, indeed, the captain got up.

Dawn was about to break, but it was not yet daylight. The feeble glow of a candle that presently lighted Henry Norton's hasty toilet fell on the objects accumulated in the cabin in such a way that made them barely perceptible rather than identifiable. Nothing is less cheerful than such an abode[3] although it is fashionable among obstinate landlubbers to rave about naval luxury. If what they have in mind is a French warship, the captain's quarters, designed on a model as invariable as administrative infallibility, are painted white with gilded baguettes copiously reproduced as in a restaurateur's private rooms; and the furniture is red, unless it is a vice-admiral who is being accommodated. Confronted with such a powerful consideration the maritime administration retreats

in order the better to triumph, and so inevitably everything becomes yellow. The laws of the Persians and the Medes or Minos's decrees could not be more absolute. On the table a few journals are neatly stacked, a Navy List, and that is all, unless the officer is a father and has decided to decorate the bulkheads here and there with family photographs.

In the English Navy individual taste is given more latitude. The captain's quarters are not always decorated in the same color: the occupant's desire can determine the matter; there are fewer bulkheads and small compartments, fewer doors shutting off four-foot-wide cubicles; more curtains that permit air and daylight to enter; and, a characteristic and curious fact, one frequently sees there paintings, knickknacks, and, above all, books. In this last regard, Henry Norton's cabin was rich in spite of its small size. Etchings done after old Italian masters, two or three little canvases bought in Messina and Malta, and, wherever it had been possible to mount them, shelves with volumes of various sizes and thickness: mathematical treatises, books on economics, history, German philosophy, recent novels, they all lined up, thronged, trampled, climbed upon one another, and some were still strewn on chairs; Henry Norton was a passionate admirer of Dickens and Tennyson,[4] which did not prevent him from doing his job conscientiously and from knowing everything about it. Having reached his thirty-third year with a pleasant, fair and mild face, he spoke little, thought a great deal, dreamed a fair amount, displayed that mixture of positive and romantic spirit and of energy so common among his compatriots; and, though very advanced in his career, since he already commanded a ship, he did not especially enjoy worldly entertainments. However, no tendency to spleen had ever manifested itself in him.

When he was dressed, he went up on deck and from the deck to the bridge; the regulation washing down was well on

its way; the din of buckets of water vigorously splashed on the deck and the noisy swishing of the swabs were making their usual racket. Norton silently returned the salute addressed to him by the navigating officer, who was wrapped in his greatcoat like any good man who has arrived at the end of his night watch, and surveyed the scenery unfolding around his ship. Dawn was rising and made Norton keenly aware of the wisdom of the ancient poets, who saw and described it as rosy-fingered; in a general way, no other part of the world inclines one to personify natural phenomena to the same extent as the Levant. All things manifest themselves there with such clarity, are delineated with such precision, reveal so much life, clothe themselves with such charm, that it seems natural to imagine the gates of the day opened by an enchanting maiden, and the shining star triumphantly drawn across the celestial field by the fiery and sparkling horses of the most handsome and most intelligent among the gods. The calm, the profoundly calm sea, blue as a periwinkle, not wrinkled but prettily pleated so as to make the sparkling cascades of young light flowing from above shimmer on its bosom, was gathering from very far, from the extremity of the eastern horizon, what was left of the delicate hues of the morning's twilight. With abandon and in larger and larger circles, it took on the saffron or pale pink tinges of this shower of blossoms. Little by little the saffron turned orange, the pink was splashed with scarlet, gold veins ran through it, and a dazzling, hot, imperious light electrified all nature.

Here and there islands emerged, some near, some farther. Soft, round, finely etched shapes outlined the contours of these mountainous lands; there lay Paros, here, her sister Antiparos; farther away in the mist, Santorin; finally straight ahead, Naxos, beautiful Naxos, was beginning to show not only its general configuration but its peaks, its hills, its valleys, its gorges, its rocks; and the town loomed up, white as a bride.[5]

It took a few more hours, however, to reach it. The breeze was extremely weak, and the ship moved slowly. Meanwhile, the details of the coast showed more clearly moment by moment. They could see the harbor entrance lying deep between the rocks, and, to the right of it, this small, barren islet, still enriched by a few patches of ancient walls, vestiges of a temple to Hercules. The houses bathed their feet in the water, stacked one upon another like the stalls of an amphitheater, and on top of these plebeian buildings there rose, with more gusto than grandeur, the group of dwellings that are called the citadel or castle, a designation that the remnants of ancient ramparts now crumbling or used to build new habitations more or less justify, though it has become a bit ambitious. This sight was fresh, gay, amiable, welcoming. The Aurora continued sailing slowly toward this hospitable shore, when an incident occurred that no one had counted on and that almost radically changed this peaceful arrival.

At the very moment when the corvette crossed the entrance to the port, a lively breeze impertinently rushed in off the sea and suddenly filled the sails, which were full spread to catch the light airs they had been sailing in. The ship took off wildly, and since she was not three hundred yards from the rocky shore, she was inevitably going to be dashed to pieces, when the captain quickly gave an order. The whole crew sprang up on the deck, from the deck into the yards; it was executed so promptly that dozens of caps and hats flew off and were strewn upon the sea; but even the smallest canvas was taken in instantly and the Aurora came to a sudden stop, not soon enough, however, to prevent a small part of her planking from plowing into the rocks; nevertheless, there was not, properly speaking, much damage, for which they were all congratulating themselves; and once they were certain that the only consequence of the danger they had skirted was the quasi-necessity of stopping at Naxos for five or six days at the most in order to replace a few planks, and since in

any case the engine also needed some repair, the captain and the officers, instead of deploring the accident, were delighted by it. The order was given to drop anchor, and while it was being executed, two persons were seen climbing on board and asking to speak to the commanding officer.

Both of these newcomers wore tailcoats, trousers, black waistcoats, white ties, and held in their hands the felt hat in use in all civilized nations; but this attire, in itself unremarkable, made a strong impression on Henry Norton, for in this instance, it produced the most absolutely archaic appearance this sort of apparel could. The most superficial of observers would not have dated it later than 1820. Their huge bulging collars, gathered sleeves, wide at the top, very narrow at the wrist, very high waists, disproportionately long tails, cossack trousers,[6] and widely opened black silk waistcoats would have moved George Brummell to tears, could he have returned to this world to contemplate these souvenirs of his youth;[7] their ample, wide, fluffed, six-inch-high cravats, adorned with carefully studied knots complicated enough to drive an ablebodied seaman wild, were proudly crowned with two starched shirt collars that must most certainly have been in perpetual combat with the brims of their hats whenever they covered the heads of the owners of these remarkable wardrobes; but at the moment the hats rested in the hands of their proprietors. One should not, however, pity these singular instruments, each one a foot and a half high, equipped with brims of a redoubtable width; they were large enough to defend themselves, and their hairy and bristling appearance gave them a fierce aspect. Norton remained awestruck at the sight of this attire; he was reminded of the heroes of another age, and he had to make an effort to focus his attention on the faces of the two newcomers. They were of a most respectable and dignified kind. They resembled each other in that their hair was cut, like their clothes, according to an old-fashioned taste, so as to form lovelocks not unlike the ornate pavilions

that accompany great monuments, while vast gray toupees, rising nobly on top of their heads and crowning the expanse of their foreheads, were even more reminiscent of those rigid pediments that draw the respectful attention of the populace to courts of the first instance.

So much for what the two islanders had in common; otherwise, they were different. The one walking in front was short, slightly fat, of rather ruddy complexion, smiling and happy; the other, to the contrary, was slender, extremely thin, of almost sallow complexion, seemed suffering and sad, but resigned. Norton could not help finding their features extremely distinguished; their antiquated appearance did not belong to just anyone, and memories of certain types of French and Italian gentlemen he had met in his early youth came to his mind.

Moved by this impression, and eager to know to what extent it was justified, he had the visitors come down to his cabin, and politely inquired what brought them on board. The fat and cheerful Naxiote introduced himself as M. Dimitri de Moncade, consular agent of Her British Majesty. He had come to offer his services, and introduced his friend and companion, M. Nicolas Phrangopoulo,[8] consul of the Hanseatic Cities. The conversation was of course in Greek; Henry Norton spoke this language fluently thanks to a sojourn of several years in the Levantine seas, and neither M. de Moncade nor M. Phrangopoulo knew the first word of another tongue.

After what has been said already about the Aurora 's captain, one can see that he was by nature curious and eager to learn. The appearance of the two characters sitting in his cabin had whetted his appetite sufficiently for him to want to know a little more about them, if only to serve as an introduction to his future observations about the island of Naxos. He therefore conducted the conversation in such a way as to gather as much information as civility allowed,

and his efforts were not fruitless. Here, roughly, is what he learned piecemeal:

The gentleman consul of Her Britannic Majesty owed his position to the fact that his father and his grandfather had already filled it with distinction; naturally, he was rewarded by the glory that was reflected upon his person and not by any sordid financial consideration. He had known Admiral Codrington,[9] and proudly remembered a lunch he had attended on board the ship commanded by that great seaman, about the time of the battle of Navarino. Approximately once every seven or eight years an English warship called at Naxos, much to his delight. In 1836, during a trip to Athens, he had been able to learn a great many interesting things he had never suspected until then. He asked Henry Norton news of His Grace, the Duke of Wellington, and appeared extremely upset upon learning that this illustrious captain was no longer alive. He celebrated this latter's extraordinary merits in a few well chosen, sententious words. This was probably the last funeral eulogy pronounced over the ashes of the victor of Waterloo. Once that sad moment had passed, M. de Moncade ventured a few sarcastic observations against the French in general and against the revolutionary spirit in particular, and without saying so clearly, he let it be understood that as far as he was concerned, he found little pleasure in recollecting the Greek War for Independence in view of the fact that the Athens government deemed it proper to send an eparch to the island, while never, absolutely never, had one seen a Turk of any kind there as long as the Sultan ruled over the Archipelago.[10] As for him, he reserved his esteem for the old families, people of noble race, that is of European origin; he could not for a minute forget that his ancestors had come from the south of France, where their name possibly still existed, and he knew for a fact that no misalliance had altered the purity of the blood flowing in his veins. M. de Moncade, livelier and more talkative than M. Phrangopoulo,

made sure most of the time to talk on behalf of the latter. This is how Norton learned that M. Phrangopoulo was no less a gentleman than Her Britannic Majesty's Consul in spite of his Greek- sounding name, which was moreover one more evidence, since it meant: son of a Frank , the real name of his ascendance having unfortunately been lost and forgotten. All of M. de Moncade's political and social opinions were shared by his friend, who approved them by nodding; but that same friend fell far short of knowing as much about the matters of the world.

In his whole life he had never left his island. He represented the Hanseatic Cities in the same hereditary way that M. de Moncade did Great Britain. But, less fortunate than the other, he would never have set his mortal eyes on a citizen of the German powers to which he belonged, if, in 1845, a merchant brig from Hamburg with a cargo of lumber had not been blown off its course by a squall and driven on the rocks of Antiparos. A wreck had resulted in which the cargo had been lost; but the crew had been rescued; and after a one-month sojourn in Naxos, the skipper, Peter Gansemann, had handed M. Phrangopoulo a certificate to be used as might be thought proper by which he informed the most distant posterity that M. Phrangopoulo was the most honorable man he had ever met and that he had fed him and his crew during their forced stay on the island, a generosity the more meritorious, the grateful captain added, as this worthy consul had seemed to him to be living in a condition bordering on misery.

Without being overoptimistic, one is allowed to believe that many good deeds find their reward in this world. At any rate, M. Phrangopoulo found his inasmuch as Captain Gansemann's sojourn was a landmark in his existence. Since the latter spoke only German, he did not communicate many new ideas to his host; but he remained a hero of the capital event in the annals of the consular establishment, and the old

gentleman's mind embroidered on this theme in such a way as to make of it rather a tale from the Arabian Nights .[11] He appreciated his certificate the more for never having found the opportunity to have it translated and for having no more idea of what it said than if the four books of Confucius in their original version had been put in his hands.

Henry Norton's imagination did not need much stimulus to be aroused. In this circumstance, it was excited by contact with such singular characters. An island of the Greek archipelago in all its marvelous grace represented by two old relics of European nobility, these two relics able to speak only Greek, and, in these gossiping days when everyone is more aware of his neighbor's business than of his own, completely ignorant of what was going on in the world outside, as though they wished to prove by their rare ignorance that their island, though only a few hours from Athens, was in fact farther from civilization than the central regions of the Americas: this was the kind of violent paradox that the captain of the Aurora adored. However, this one seemed so extreme that before savoring its charm, he wanted to see it demonstrated, and his impromptu friends did not need to be entreated to do so fully.

No mail boat travels between most of the islands and continental Greece for the excellent reason that these tiny territories, having neither commerce nor industry, neither import nor export, do not occasion any exchange of correspondence. Each fortnight a schooner sails from Syra[12] for Paros carrying the few letters and packages addressed there, and when by very rare chance there are any for Naxos, some boat or other casually takes charge of them; this mode of traffic is perfectly sufficient. By this means newspapers get to the island; but what interest can they arouse in a people confined at home and with no desire to leave, who never read, know nothing about the events of this world and do not care to know anything about them, whose only posses-

sions are a few vines, some olive, orange, or pomegranate trees, and here and there a few sheep, and who, like the man in Horace's ode,[13] live in a kind of simplicity that, by the way, is anything but golden? However much these practical philosophers might learn in this desultory fashion, they retain at most a few unexciting subjects of conversation; and so, too poor to need anyone, clad and fed well enough under an amiable sky not to suffer in any way from this charming poverty, self-assured in their indolence, proud of the past and able to preserve the dignity necessary for the present, the Naxiote gentlemen live peacefully and believe themselves to be not one grain beneath the most frantic men of the most turbulent modern society.

Naturally they have in common with all inhabitants of Hellas a solid veneration for the origins of their country, and they claim as their own a share of the shining halo hovering over their heads; but it is especially the time of the Crusades that they like to recall. It is then that the French duchy of the Cyclades was founded and that the knights carved fiefs for themselves out of the islands. Most Naxiote gentlemen trace their genealogy back to those times,[14] but in this regard many are mistaken. The French duchy has since then known many ups and downs. One by one the conquering races were extinguished and replaced by others actually not any less Frankish, but less ancient; the Venetians brought the Italians there in great numbers; seventeenth-century French and Spanish adventurers contributed their share; some Greeks as well. In brief, when the last heir of the European ducal house had been forced to relinquish his power to the Turks, the latter, in truth, did not change anything in the political constitution of the island, and did not dispatch representatives of Islam there. They went even further; they installed a duke of their choice, who happened to be a Jewish physician of the Sultan.[15] But since that son of Moses had no successor, and as he had never resided on the island, his palace,

which had become the nominal property of the Sultan, was abandoned and little by little demolished by the nobility who found it convenient to avail themselves of cheap building material from structures that were neither reclaimed nor protected nor repaired. And from then on the local government became completely municipal and republican in the hands of the old families. Nobles and commoners, the one as poor as the other, accustomed to coexist, forgotten by the rest of the world, with no reason to quarrel since they had nothing to quarrel about, lived and are still living together in perfect harmony. The Catholicism of some and the Orthodoxy of the others, the presence of two bishops of opposite persuasions, a convent of French Lazarists who had come heaven knows why to buy land there, the founding of another convent of Burgundian Ursulines,[16] nothing had been able to prevail against the obstinate amiability of this population daring to live in the nineteenth century in a more or less Edenic state.

Once the conversation of his two guests, whom he had invited for lunch, had made this situation clear to him, an enchanted Henry Norton prepared himself to go ashore and take a closer look at such interesting things. After giving his orders to his second, he boarded his gig with M. de Moncade and M. Phrangopoulo, and followed by Dido, no less pleased than he to go ashore, he headed toward a small wooden wharf where a substantial portion of the population, that is a dozen fishermen, was awaiting him in a state of cheerful curiosity.

A few women held beautiful infants in their arms. They all greeted the stranger good-humoredly; and flanked by his sponsors, he walked up a narrow path through all kinds of ruins, rubbish and empty patches and after a few minutes of a fairly steep climb, he reached a low door, the last remains of the citadel. This rather dark entrance brought him to a narrow street paved with flagstones. It was the main street; it serpentined upward between two-story houses that imitated eighteenth-century Italian architectural forms. On each door

a coat of arms was embossed.[17] This dark and cool street was so little used that it resembled more the courtyard of a private house than a public thoroughfare. Now and then a mule loaded with wood, vegetables or fruit made its way, gingerly choosing its footing.

M. de Moncade stopped in front of an arched door whose keystone, like the others, bore a coat of arms, and with a deep bow to the captain, he begged him do him the honor of resting a moment in his house, a kindly request as soon granted as made, and pushing open a worm-eaten leaf of a double door, Her British Majesty's Consul in Naxos introduced Henry Norton into a large, vaulted room, similar to one of those cellars in which rich European abbeys liked to gather their casks and barrels filled with the pride of their vintages.

Daylight entered this solemn place only through a wide opening in the middle of which the door had been situated, and whose wooden frame also enclosed a row of three windows. The walls were whitewashed. The floor was paved in the same fashion as the street, of which it was simply a continuation, being on the same level with it. At the back of the dwelling an old and extremely worn carpet was spread, and a few pieces of furniture were scattered there: a wooden cabinet carved in the Venetian manner, two or three armchairs covered in yellow Utrecht velvet, straw chairs and a table adorned with Florentine alabaster vases. Portraits of Queen Victoria and of her Consort, evidently executed by a mortal enemy of the Hanoverian dynasty, were pointed out to the captain with no little pride. Few such masterpieces existed on the island.

No sooner was Norton seated than he was overcome by a strong desire not to spend his day looking at the rounded white vault above his head; consequently, he consulted his friends on the best way to use his time. It was taken for granted that they would not leave him for a minute, and he

realized that for him to demand solitude would both pain his hosts and grievously hurt their feelings. This first point was therefore discussed only to the extent that discretion seemed to require it. Norton realized then that it was out of the question for him to shroud his sojourn in a futile incognito. The appearance of a warship in the port of Naxos was such an extraordinary event that the entire social life of the region was affected by it; it was talked about everywhere; the great news flew on the wings of fame with such prodigious speed that before long it had gone from one end to the other of the most solitary vales. From then on nothing was more necessary than satisfying the just curiosity of the notables and going to show the bishops and the two or three representatives of the greatest families of the country what an English captain was like, a sort of entity about which the most learned had heard, but which none had seen. Once this duty was done, they would go to M. Phrangopoulo's in the country and would pass the rest of the day there.

With this program settled upon, Henry set about complying. On the doorsteps men, women, children were gathered and greeted the stranger with the warmest smiles in the world. These good people gave an impression of nonchalance and calm that comes from leisure and from the absence of want. The beauty of the majority of women was stunning. A magnificent sky, an excessively picturesque town, very small and self-contained, and quite similar to the nest of a single family,[18] an unfailing peace, many extremely charming faces, good humor on all of them, such was the newcomer's greeting, and he was not the kind of man who would not be stirred and moved by it. It had not been two hours since the two gentlemen had shown up on the Aurora , and Henry Norton no longer found them ridiculous or even strange; he no longer perceived anything other than their exquisite politeness, their desire to be agreeable, the true distinction and the native nobility of their manners.

During all their visits, coffee and cigarettes were offered. Questions regarding the state of Europe ran their legitimate course, and once these indispensable preliminaries had been taken care of to the satisfaction of all, especially that of Dido, who was in a hurry to see them end, the three friends left the walls of the fortress and the field of ruins covering its slopes and passed behind a hovel where they found three mules sent for by M. Phrangopoulo, which were to have the honor of transporting the voyagers.

In Naxos, following the paths bordering the sea on foot would be, if not an impossible task, at least a difficult and tiring one. Sand is everywhere, a drifting, fine, deep sand; high, thick, flowering hedges hold this unstable soil and cling to the rocks that surround it. The way is like that for several hours. The sky laughs, the sun burns. Then the mountains loom up one after the other, rounded, cut by deep ravines. A few live oaks, lentisks; at the foot of the slopes, delightfully cool brooks and masses of oleanders. A few cattle wander here and there. On the hills little square castles of a dazzling white, with few windows, and at the corners four round-roofed watch turrets rise like graceful and unruly children. A few are crenellated. These miniature, quite feudal manors make a singular impression on a Greek island. They are vestiges of the time when the Barbary pirates sailed the neighboring seas, attempted bold landings, and, kidnapping fair lasses, went to sell them in the markets of Constantinople, Alexandria, or Smyrna, thus giving birth to a quantity of romances,[19] most of which remain unpublished. Reluctant to be made the raw material of these poetic incidents, the inhabitants did not dare dwell on the beaches; and that is why in the whole Archipelago, the habitations always tower from the highest peaks and whenever possible from heights that overlook the open sea.

Nothing could be prettier than these castles; they are surrounded by vines, enormous orange trees, figs, peaches,

and by plantings of all kinds, carelessly kept undoubtedly, but even more lush, free, and hardy for that.

After traveling two or three hours, they came upon one of these little castles on a hillside. Whiter than the others, more attractive, more elegant, more stylish, its four towerlets rising more exquisitely, surrounded by greener, denser trees, bearing more lemons and oranges, more intricately garlanded with vines, it immediately drew Henry Norton's attention and held it. It was a kind of fascination; and when M. de Moncade, who did most of the talking, had announced that it was the goal of their excursion and that, after crossing a small bridge over the brook, they would arrive at his friend's property, the English voyager felt as if he was about to cross a Rubicon of sorts and leave his former life on one bank in order to start a new one on the other. Such visions happen sometimes and are deceived; they depend on the mood one is in, on the weather, on a better awareness of physical well-being. Not only are high-strung natures set in motion a thousand times by almost anything or by nothing at all, but, what is worse, they tend to give in to the belief that their oscillations are of prophetic importance and reveal the future to them. It happens, therefore, that they are misled; but to take as axiomatic that they always deceive themselves would only be a special kind of superstition.

In this case, this much is certain: Norton approached the little manor with a wide-open heart, a soul exalted by an inexplicable joy, and a mind abandoned to the caresses of a thousand ideas, a thousand thoughts, a thousand feelings, each keener, gayer, more animated than the other.

Naturally, Naxos being a mountainous island, one is constantly climbing or descending. Here the travelers ascended one more winding, rocky, and very steep path, and were thus guided through a few courtyards and in front of peasant houses to the top of the rise where the manor perched; and dismounting at the bottom of a narrow stone stairway, they

reached an equally narrow terrace that led into a room very similar to the one Norton had already admired in town in M. de Moncade's house. It was likewise a long whitewashed cellar, vaulted like a chapel, flooded with light, and more simply, or if one prefers, even more meagerly furnished. A low sofa covered with calico dominated one end of the room, and at the other end, a very light wooden stairway climbed to a gallery leading to a small low door that gave access to the family's living quarters. One immediately gathered that in ancient times when, out of fear of raiding pirates, the castle had been built on a peak, they had taken the further precaution, in case these fearsome invaders managed to land unnoticed, of being able to abandon the lower part of the dwelling by taking refuge in the upper, easily isolated by merely kicking down the stairway. In all, the manor had only four or five rooms, and, flanked by four turrets, was surmounted by a flat roof on which at present the crop of maize was drying.

All this was visited and examined by Norton in the greatest detail, and when he had got his fill of the beautiful landscape surrounding the old Venetian abode, he returned to the great hall, where a scene of another kind was awaiting him. The feminine portion of the family was gathered on the sofa. There was the mother, Madame Marie Phrangopoulo, a respectable matron rendered little mobile by her sheer weight, who was gravely turning the beads of her rosary between her short, round fingers. She had the great black eyes common in the region and an expression of total repose; not a trace of animation, but some twenty years earlier she must have been what is called a beauty. The lady sitting next to her, whom Norton understood to be her daughter-in-law, was a brunette; she had strong features, with wonderful lustrous black hair, eyes of a depth that made one ponder. Perhaps that depth contained nothing, but it was a mystery not to tamper with: she was Madame Triantaphyllon Phran-

gopoulo. Two little boys were hanging on her skirts, one with chestnut hair and the other dark like her, both as beautiful as angels and both staring at the stranger with that look of implacable mistrust and profound admiration always so beguiling in children. The young woman held a third baby in her lap, and it squeezed between its small pink hands an orange, the focus of all his faculties; a little girl a few months old was carried in the arms of a young Syrian servant, and on that subject one must say that the entire past of the islands is very exactly reflected in their present. In ancient times, the Cyclades saw more Asiatics settle on their shores than Greeks, more Phoenicians than Hellenes, and the antiquities found on them reproduce more often the monstrous idols of Tyr and Sidon than Athens's elegant divinities; things have remained about the same nowadays. Athenians are in no hurry to end on these shores where the seductions of nature vainly compete with the attractions of the great Constantinople, the bustling Smyrna, the opulent Alexandria: on their side, the peoples of Canaan have not forgotten the old routes, and that is why one encounters servants of their race in Naxos, where they mix with the descendants of the knights of the Crusade.[20]

Norton was turning these things over in his mind when he heard the door of the upper gallery open. So little did he expect to see the person who came out of it that he at first believed himself the victim of a dream. It was a young woman more than plainly clothed in a brown cotton dress with white polka dots, most certainly cut and sewn by herself which not only did not enhance her appearance, but barely passed as a garment. Full sleeves gathered at the wrist; no lace, no voile: nothing could have been more austere. A slender, strong, firm, healthy figure, the complexion of one of Rubens's Nereids;[21] marvelous eyes, as bright as blue sapphires and with the same limpidity as those stones, and her hair, golden, thick, abundant, coiled with some impatience,

it seemed, over the trouble it took to tame it, although it was much finer than silk and miraculously supple; the pinkest of mouths, the most generous of smiles, teeth most worthy of the ancient comparison with a row of pearls; and an adorable and flawless candor that was evident at first glance; above all, a serene charm that comes from security.

Does love start with the first blow, or only after several wounds? It is a kind of question discussed by learned doctors. But it would seem that love must work in the same way as death, which, according to the Holy Scriptures, is the weaker of the two.[22] When one has not been killed by the first stroke, it is because the blow was ill directed; but the thrust that knocks you down for good does not need the previous ones. In the same way, when love does fell you, it can do so because its aim was right, and thus one is indeed in love from the very first moment. Norton would probably have challenged that axiom. Proud people never like to see themselves overcome at the first encounter. Still, when, having reached the bottom of the stairway, the young lady crossed the long hall to come and sit by her mother, the captain felt it necessary to call to his aid all his civilized rigidity to hide his emotion, and he forced on himself a cold and starched air worthy of the British flag. He was not in the least to blame if the supple, noble and extraordinarily graceful walk of the newly arrived brought to his mind the hemistich from Virgil on the way the goddesses move;[23] even less to blame when, once the young lady was seated, he saw the eyes of the whole family fixed on his and all their mouths smiling with the most open pride, while M. de Moncade was saying to him, with the air of a man exposing an incontestable truth:

"I take it that you have never seen anything as beautiful as my Goddaughter, Akrivie?"

They all seemed to await the captain's answer in absolute confidence. The object of this remark smiled without any embarrassment, and seemed convinced herself that

it was impossible to dispute what had just been said. Dumbfounded by so unconscionable an offense against all custom and against the most sacred conventions, Norton assumed an embarrassed attitude and bowed. It would be impossible to swear that he did not feel rising in some corner of his brain one of those ugly suspicions that the cultivated do not lack. But if such a disgraceful thing did occur, it must be said in his praise that he did not permit this shameful notion to become a conscious thought, and the only result was that much to his credit he brushed British cant aside and answered M. de Moncade unperturbedly:

"I did not believe that anything as perfect as the young lady existed.

— It is not, the British Consul continued, that my Goddaughter has no worthy rivals on our island. When you come to mass on Sunday, you will see that our girls are pretty; but you won't find another like her. It's an incontestable fact, and she is not sorry about that. Do you want a cigarette?"

Tobacco was passed around. Norton said to himself:

"I am crazy or on my way to becoming so. She is pretty; why deny it? But as dowdy as can be! She seems graceful to me because I am on Naxos and I see her through a tangle of orange trees and oleanders; in a London drawing room things would be different. I can already hear Lady Jane's kind observations. What a massacre! And what's more, what sort of upbringing has this unfortunate child had? She must be utterly silly! I must make her talk."

In the Levant, people who are well disposed toward one another and happy to be together willingly enjoy that pleasure hours on end without opening their mouths. They stay seated, they smoke, they look at one another, they are contented, they do not say a word, and they do not have the slightest desire to be witty. It is what explains why the inhabitants of those countries are never bored. Norton would therefore have prolonged indefinitely his self-absorption with-

out it seeming out of the ordinary. The master of the house, helped by a young servant, was expertly preparing lemonades. Madame Marie was beatifically telling the beads of her rosary. Madame Triantaphyllon gently rocked the fat baby, who, having succeeded in making a hole in his orange, had fallen asleep sucking it, and the two boys had left with the Syrian servant and the infant. The beautiful Akrivie openly looked at the stranger, and without malice she contemplated him as though he were a human specimen different from any she had ever before seen. As for M. de Moncade, he was smoking with a gravity quite worthy of respect from a Mohican chief sucking hard on his calumet.[24]

Condescendingly pursuing his plan, Norton tried to strike up a conversation with Akrivie, with the immediate aim of inventorying the furnishings of her mind before going on later to those of her heart. It was the remedy he had found against the too sudden commotion he had undergone. Her mind appeared singular to him; he saw none of those things that usually adorn a young lady's imagination in those happy countries where good upbringing and distinguished salons flourish. To tell the truth, she knew nothing at all and did not seem to have the faintest idea about the use of being other than she was. By chance Norton discovered that she thought Spain bordered America, though, other than that it lay in a part of the world in all probability rather distant from Naxos, she had no idea where it was. He was pedant enough to try to correct her notions on this subject. She let him talk and did not seem to pay the least attention to his words. He found her responsive to the prospect of seeing the Christians retake Constantinople, and, contrary to her father and godfather, was quite vehement against the Turks, whose total eradication she ardently desired. She did not doubt for an instant that those monsters eat children alive and believed them on the verge of making new raids on the island. Seeing that her political understanding was strongly imbued with

the stuff of poetry, Norton tried to put her on the subject of literature; there she displayed a total vacuum: she had never read anything apart from her prayer book, and had never thought about it. He was astounded that this imagination, which was capable of conceiving such singular things on the subject of the future conquest of imperial Stamboul and of staging it with such rich inventions, did not seem to find the least charm in the printed pages of a book. He tried to fall back on an analysis of the picturesque beauties of the island and of the sea. Akrivie seemed flattered that the English gentleman found the country to his taste. Since she did not know any other, she was utterly convinced that it was the most beautiful and lovable in the world; but precisely because she was lacking means of making comparisons, she seemed indifferent and unresponsive to his enthusiasm on the subject. Thus she talked about nothing, knew nothing, had thought about nothing, and had not had what one would call a conversation on anything. Meanwhile, she smiled, opened wide her beautiful eyes; and she was ravishing.

Norton was not able to find her a simpleton. In fact, what happened was totally the opposite. Flashes of the most faultless judgment, of the most self-assured and absolute conviction, an obvious vigor, a decided health in this practically uncultured mind gave him more food for thought than would have the most flowery outpourings which, in a mind as sophisticated as his, would for the most part have done little more than revive old memories and stir up stale quotations. The conversation carried not across a sterile plain but onto uncultivated land, which is a quite different matter for one trying to survey the resources of a country. He did not find there what he was looking for; but he sensed things of which he knew neither the name nor the use, nor the intrinsic worth, but which however were precious. The more frankly Akrivie laughed, and the wider she opened her large eyes (while looking at him) seemingly disposed to let him gaze into the depth

of her soul, the less he understood her. So it soon happened quite naturally that to the pleasure of seeing such beauty was added that of finding her the more mysterious for her being truly unaware of it.

She showed her femininity on an essential point. By chance and as though from an inspiration, he had the idea to talk about clothes. Here Akrivie's interest was visibly aroused, as well as her sister-in-law's, and even her mother stirred out of her lethargy. But Norton realized that to be really understood he could not aim too high; Akrivie and Mme Triantaphyllon sincerely considered a velvet dress as the acme of human elegance and gold bracelets as likely to gratify all the wishes of the most demanding woman on earth. As for fashion, strictly speaking, they had only the vaguest notion of it. Nonetheless, Norton was not bored; he even became more and more involved as intimacy increased, so that it came as a surprise when his host told him that if he wanted to go back on board that same evening, an intention he had firmly expressed several times, it was time to start. But they begged him so warmly to come back the next day that he willingly gave his word.

People in love, like spirits animated by a god, probably enjoy illuminations refused to other mortals. They tend to make momentous incidents and extraordinary revelations out of facts that sober heads would consider insignificant. Ordinarily a sensible man, Norton was noticeably preoccupied with Dido's behavior during that memorable day. When Akrivie had made her entrance at the top of the stairway, Dido had left the spot she had chosen at her master's feet, where, with her head resting on her two forepaws, she had visibly meant to recover from the rigors of the excursion. Staring at the young woman during the whole time it took her to descend the steps, she went over to her and, seeing her advances ignored, had followed her affectionately to the sofa, had sat down, and from then on kept fixed on her

her large black eyes that shone like carbuncles in the midst of an even blacker fur. She did not lose sight of her for a moment during that long visit; two or three times, she had placed a heavy paw on the knees of the person who inspired in her such a lively sympathy and had succeeded in being petted, much to her obvious contentment. At last, when it was quite clear that they were leaving, Dido had to be called three times before she obeyed her master, who was deeply struck by such strange behavior on the part of his favorite. Nothing like that had ever happened; up to then Dido had not let anyone distract her from her absolute affection for Henry, and even Thompson himself, the great and powerful Thompson, in charge of the details of her domestic life, who thought he had always held a distinguished place in her esteem, had not been able to inspire in her anything resembling such favor. Norton was almost frightened seeing Dido as little sensible as he himself was.[25]

It was late when the captain, after taking leave from his two kind and excellent hosts, had returned to the Aurora . Climbing the ladder, seeing the duty watch, who met him with a lantern, answering the officer's salute, he reentered his everyday world, one where he was accustomed to feel comfortable. But this time he did not experience the same impression, and he dealt with the realities as rapidly as he could so as to immerse himself again in the dream. Still he had to listen to the mate's report. All was well on board the Aurora . The very light damage was on its way to being speedily repaired; the officers had spent the day ashore and had found an admirable place to stage a cricket match, which had been most exciting. They planned to have another the next day. According to the cook, fine mutton had been bought, also fresh vegetables whose exceptional flavor had been appreciated at dinner time. The mate assured his captain that Naxos was a wonderful part of the

world. Norton was much afraid that he shared this view of things only too much, although for other reasons; he went below to his quarters, followed by Dido in whom he perceived, not without some fear, preoccupations similar to his own.

But he was not able to remain lying down. He lit a cigar, went back up on deck, and began one of those monotonous pacings that sailors are given to, in which they generally work out the unmanageable part of their reveries, their suppressed desires, their unrealized plans, their most burdensome worries. From the extreme stern to the foot of the mainmast, he went back and forth, his spirit a thousand leagues from the world of planks and ropes in which his body moved. The night sky was of a limpid depth, the moon glittering, each one of the thousands of stars ablaze; and indeed his soul was not less ablaze in himself.[26] Like a general, it was reviewing a strange array of charming creatures to which, since it had been capable of self-examination, it had devoted, if only for a week, a feeling of tender imagination. The fresh, finely chiseled features of the Irish girl, the object of his daydreams after he left Eton; Molly Greeves, who had cried so much when he left her uncle's house at the end of his first leave; Catherine Ogleby, to whom he had been engaged, and who had married an officer of the guard while he was in China; Mercedes de Silva in Buenos Aires, Iacinta in Santiago, Marianne Ackerbaum in one of the Baltic ports. In truth, he had loved the lot of them, more or less, but he had loved; he had hoped, he had believed, he had been moved, he had experienced pleasure, grief, fear, boredom, sorrow, intense joy, sincere sadness. All that was left were ashes, but he had loved, and those ashes gathered together in a new hearth now helped to rekindle the fire, and in the middle, above, from fresh logs, from a new flame higher by far than all those that had formerly made him burn, his love for the girl from Naxos was soaring.

The comparisons he managed to make between the feelings that had successively occupied him and the one that had just invaded him, brought him to the undeniable conclusion that this time he loved in a new way, a stronger, more prevailing, certainly deeper, way that grasped the uttermost fibers of his being. Was it due entirely to Akrivie's beauty? That beauty, it is true, was incomparably superior to anything he had ever seen, even in a dream; yet it would not have been sufficient to perform the miracle. Nowadays one no longer loves a woman only because she is beautiful; that happened long ago, in ancient and barbaric times, but minds as sophisticated as those of our day could no longer tolerate it. When David, Ruth's energetic son, wanted at any cost to possess a certain Bathsheba, of whom he knew nothing except that she had beautiful shoulders, he had his best servant killed to accomplish that end, piled iniquity upon iniquity and almost fell afoul of Jehovah forever over that business.[27] In the same way, Paris, son of Priam, driven by the mere vision of one day possessing the most physically perfect creature in the world, upon whom he had bestowed an instantaneous and unreserved adoration without ever having seen her, eventually incurred all kinds of calamities. But those are not modern feelings, and Norton, keen analyst that he was, did not need to consider the state of his heart for long to convince himself that the tumult he saw in it did not result from sight only. From whence, then, did it come? Akrivie was not witty, showed a baptismal ignorance in all things, and devoid of the least coquetry, she had made no attempt to please or displease her admirer; if he had inspired in her any feeling at all, it was one of curiosity, and the chances were that the only trace it left in this beauty's imagination was an impression of the singularity of foreigners in general and captains in the British Navy in particular. And yet Norton sensed something more in this nature so different from that of the other women he had more or less loved; that other thing attracted

him, charmed him, in a phrase that sums it up, had made him fall in love, as he had. It took him some time to discover the secret; finally he succeeded, and that was to his credit.

The conditions of life that were Akrivie's, being exactly those of women three thousand years ago—isolation, a limited sphere of affection, total ignorance of the outside world, the same factors had worked on the girl from Naxos as one had formerly observed working on those superior characters from remote times. The young woman's native qualities had not been suppressed but concentrated, and instead of spreading luxuriously in multiple tendrils covered with leaves, flowers, fruit, they had grown straight up in strong, smooth branches, soaring toward the sky, with some charm but even more majesty, with some seductiveness but even more grandeur.[28] The whole thrust of her spirit had been concentrated on her surroundings, with no desire or even inclination to look beyond. None of her mental energies had been diverted from what she was supposed to love, and no instinct had moved her to enlarge that circle. Again, Akrivie was a woman right out of Homeric times, living, existing, finding the sole justification for her existence in the milieu in which she moved, exclusively a daughter, sister, until the time when she would become no less absolutely a wife and mother. Autonomous being is little present in such natures;[29] they are mere reflections; they cannot, would not be anything more, and their glory and their worth, which are not small, reside there. Nothing resembles less the perfect woman, such as contemporary societies have invented her and more or less created her; the latter wishes, strives, succeeds or fails at her own risk; at any rate, she is quite different from the other, and it would be unjust to compare the two. In any event, for better or for worse, this is what Akrivie was, and Norton could see it. She reminded him, for good reason, of one of those beautiful girls painted on Athenian vases, filling their amphoras at the city's water fount and, so long as the

outcome of the fight had not awarded them to the winners, impassively watching the heroes fighting and dying for their prizes.

Strangest perhaps of all was this: Norton, man of the world par excellence, used to the best and most brilliant European society, kept at the bottom of his heart, in a latent form, of which, lacking the occasion, he had never been aware, a powerful attraction for that kind of feminine temperament. At first he was surprised by it, for up to that day, he had always been attracted by the opposite qualities. On closer examination, however, he easily recognized that the charm had never lasted long; parting had taken place without causing as much pain as would have befitted a perfect love; the extreme liveliness of one of his mistresses, the sparkling wit of another, the languid tenderness of a third, had left an aftertaste—a regrettable disposition bordering on ingratitude, of which he secretly accused himself. And now he caught himself loving a sort of grown-up child, a stranger to his habits, his tastes, his way of life, his ideas, and this without any better reason to give himself than that she was visibly the exact opposite of everything that he had halfheartedly liked until then; from that he concluded that she had been born and meant for him.

It was because he was English, and English to his fingertips, English in his soul as well as his blood, that things had turned out this way. This Norman race, the most dynamic, the most ambitious, the most turbulent, the most practical of all races on earth, is at the same time the most inclined to acknowledge and practice the renunciation of things.[30] Born into a social situation that permitted him to expect a great deal, Norton had never relied on the privileges that surrounded his youth, and, out of pride as well as out of natural energy, he had worked as hard as any man without advantages would have to climb the ladder of his profession as fast as possible. He had sailed, worked relentlessly, read

an enormous amount, thought a great deal, and every time a chance to act had come up, he had never missed it. One has already seen that he had an infinitely poetic turn of mind; but he had never permitted revery to come between him and action; the world around him had only known the practical side of his mind and his judicious, honorable but undeniable aggressivity in pursuit of success. And it was precisely at that moment when, still quite young, having reached a high position on the professional ladder, when everything had become easy, that he looked upon all this with disenchantment and questioned himself about the intrinsic worth of the advantages for which he had struggled so stubbornly until then. Such was the question he had asked himself many times for several months already, and at each reckoning he found it more difficult to resolve the problem, or, speaking more plainly, he descended one step closer to a contemptuous answer. It was at this turning in his life that fate brought him to Naxos, where nothing of what he had contemplated in his past existed, and there it sent him to Akrivie.

The young captain understood it all. During his nocturnal pacing, he took a lucid look at where he stood. He saw himself tugged by divergent forces. Still yesterday's man, already tomorrow's, judge and referee between the two, he channeled the total energy available to his soul into not rushing a solution. For, he said to himself with some regret, the card I am about to put on the table in this game will be a decisive one; and I am not about to play my hand under the influence of a sublime night and a disturbed heart.

He was a logical and supremely self-controlled man. To Dido's great pleasure, who slept uncomfortably on the planks and who for a long time had wanted to stretch out on her bearskin below, he went to bed. Early the next day he was up and found most of his officers breakfasting in haste so as to resume their cricket game and to don again their strange costumes, which any true Englishman loves for such occa-

sions: high boots or colorful half-boots, tight white jersey trousers or gaudy breeches loose at the hips, red or sky blue or variously striped tunics, open-necked and sleeveless, in some cases suede gloves, outrageous caps, beribboned straw hats, and the huge bat, the game's tool, on their shoulders. It is in such attire that the self-respecting gentleman must present himself to an admiring public! Whether the scene be an English field or an Australian savannah, whether it be in sight of a Chinese pagoda or on an icy plain near the North Pole, an Englishman of good name and reputation who is going to play cricket could not possibly dress differently without being compromised. Norton wished his companions a jolly time, and having rapidly reached shore in his gig, he found there the faithful Messieurs de Moncade and Phrangopoulo already waiting for him, still wearing their antique garb and their high white cravats;[31] he exchanged two hearty handshakes with these respectable persons, and jumping on the prepared mule, he set out in their company for the manor.

The day did not go well for Norton, although actually no tangible incident took place. But people in love have their own way of assessing what happens. The English sailor's reception by the ladies, however, was more cordial than it had been the day before if only because they knew him better. Madame Marie was no more loquacious, but she seemed more at ease. Madame Triantaphyllon enjoyed seeing her youngest child in the captain's arms tugging handfuls of his hair, obviously without any fear. Akrivie acted as unconcerned as before, but Norton, and that is what hurt, had wisely concluded that this great calm showed only too clearly that he had made no impression on her and that there was reason even to believe that he could never make one. This word, "never," is bound always to occupy an important place in the vocabulary of people in love.

Again, nothing happened except that Norton was more confirmed in his convictions regarding the beautiful Naxiote's

character, and as there was clearly a struggle going on inside him between the civilized man who wanted to be loved and felt that he wasn't, and the bored and quasi-jaded man quite tempted to burn what he had adored and to adore what he did not know, he went back on board on the one hand contrite, swearing that Akrivie was a silly girl, without soul and without warmth, and on the other, disposed even more than the day before to find her a noble soul, quite worthy of being his initiator into a better, more rational and more truly masculine life than any whose ways he had followed until then. He did not take his walk on deck, went to bed instead, but Dido was the only one to sleep. As the cricket game had had its share of incidents well worth comment, Norton heard animated discussions going on late into the night in the officer's wardroom. He had not slept a wink when daylight got him up, and after giving his orders to the mate and listening to the various routine reports, which, perhaps for the first time in his life, seemed to him completely ridiculous and sovereignly insupportable, he went to meet his two hosts, more than ever clad in their immortal black suits.

The third day was marked by a momentous event. Norton proposed an excursion at sea to his friends, and the occasion for it was provided by the pretext of going to see how things stood with the volcano that had recently appeared on Santorin.[32] This grand phenomenon had started, or rather resumed, only a few years before, and the captain praised the prodigious character of this spectacle in order to pique the curiosity of the manor's inhabitants. Mme Marie shook her head disdainfully, and was unshakable in her resolution not to budge; Mme Triantaphyllon confessed that she would be very pleased to see what the English corvette was like; that is all she was interested in. Akrivie showed a little more interest; like her sister-in-law, it was principally the corvette that attracted her; but she did not dislike the prospect of a voyage. As for the volcano, she could not have cared less; a

blazing mountain seemed to her a pure paradox that left her indifferent. The two old gentlemen seemed infinitely more excited. They accepted the invitation eagerly, and, after a great deal of discussion it was agreed that the fair Akrivie would occupy the captain's cabin; her father and godfather would take the wardroom; Madame Triantaphyllon would accompany her sister-in-law on board and have lunch there, and after being given the complete tour, would return to the manor, while the corvette would take an excursion of three days at the most.

These discussions took forever; the most naive and infantile questions were asked on the subject with an extreme gaiety; but Norton was disappointed to see once more that he had not stirred in Akrivie even the most fugitive trace of emotion.

The next day everything took place as had been arranged. At six o'clock in the morning the Naxiote family was on the ship's deck. Breakfast was served and every corner of the vessel was shown to the visitors. Mme Triantaphyllon found this spectacle quite extraordinary and she forever remembered it as a strange jumble of ropes, masts, sheets of tin, copper pistons, and black smoke. What she declared absolutely beautiful was the large stern cannon, which they could never persuade her to touch even though she was dying to. When the moment came for her to return on shore, she had already been yearning to do so for two hours, for it was the first time that she had left her children for so long, and she was excessively worried. Nevertheless, she became aware that she worried almost as much about what might befall her relatives during this unheard-of adventure, and before leaving the corvette she hugged Akrivie tightly, shedding a few anguished but quiet tears on her sister-in-law's neck. Then she left, and the Aurora , having weighed anchor, began to move, and slowly sailing out of the harbor, gained the open sea.

As the ship proceeded toward Paros and as Akrivie, paying more attention to what was going on around her, was gradually losing her impassivity, Norton noticed with extreme interest that she was not as unshakably indifferent as until then it had appeared. What could be seen on the horizon or what was happening on board made her eyes shine. Henry was watching her the way a gardener follows the progress of a bud opening into a flower. She seemed to try to understand the people around her; they in turn did their best to obtain a glance from so adorable a person, for you can easily imagine that the Aurora 's officers were dazzled. The first officer stuck his chest out, displayed his white trousers, the gold buttons of his impeccably ironed shirt and his watch chain to their best advantage. The navigating officer, as busy as he was with his duties, still found the time now and then to offer an interesting remark while twisting his red side-whiskers with coquetry. The junior officers eagerly brought all sorts of chairs onto the quarterdeck and prepared drinks made with the strangest of ingredients. Only the doctor, who remained calm thanks to his sixty years, was trying to obtain a bit of information about the flora of Naxos by means of the little Greek he knew, which he used in a way quite sufficient to give Demosthenes a fit, if that famous orator had heard it. M. Phrangopoulo was answering with the description of a tree while his interlocutor was under the illusion that he was getting a monograph on a microscopic blade of grass. M. de Moncade was awed by the screw, which was making seventy-five turns a minute. What most captivated Akrivie was the midshipmen, particularly the youngest of them. Her presence made them bubble with excitement; but regulations forbade them from venturing onto the quarterdeck, and they satisfied themselves by devouring the young lady with their eyes. She, however, did not ask any questions; but Norton sensed that she was looking at everything and enjoyed seeing her do this.

When they came to Antiparos and were engaged in the channel between the island and a brush-covered islet, Akrivie pointed admiringly toward the high cliffs on shore and said to Henry: "It's marble!" It was marble, white marble, and its effect was wondrous. Sea, wind, rain, storm have vainly tried to defile these enormous masses of divine matter with their blasts; they keep their majesty and their beauty intact and display its full magnificence along these shores.[33] A few travelers have already remarked that the very fact of being built of marble, even unpolished marble, is enough to make Genoa worthy of the glorious name, Genoa the Superb. What can be said of an island whose rocks are marble and of a marble similar to that from which Venus emerged along with such a multitude of divinities which won the admiration of the world? Akrivie did not analyze her sensations and could not have found the means of doing so with her limited and virgin intellect; but Henry could see that since all expressions of beauty have something in common, she perceived the proximity and the effect of the splendid landscape rising before her eyes as through a magnetic power.

They decided to take a walk on the island, and to sail for Santorin only at night.

Everyone was in a cheerful and high-spirited mood. Agreeable as it is to sail with a pretty woman, it is even more so to take a walk with her on shore. The sea air, the unusual liveliness of conversation, the appearance of so many new things, had heightened the color in Akrivie's cheeks, and laughing heartily, she accepted the officer's joyful eagerness to take her ashore. The closer they got to the beach, the more they saw it as it was, that is rather less attractive than with its colors heightened at a distance by the purity of the air; it was now an austere, pebbly, barren spot, and the sole vegetation on it consisted of bushes and here and there a meager tree. As soon as they touched the sandy beach, Norton sent several midshipmen scouting, and almost immediately one of

these youngsters, Charles Scott, a Scotsman, came running back to tell his captain that behind a little knoll about three hundred feet from the beach, a rather large dwelling could be seen. The caravan at once started walking in that direction; and M. Phrangopoulo, after reminiscing with M. de Moncade, explained who was the owner of the domain toward which they were heading.

Five or six years earlier, a Greek from the Ionian islands, Count Spiridion Mella,[34] had come to plant and cultivate vineyards on Antiparos with the intention of competing with the wine of Santorin. Whether he succeeded or not, no one knew; in any case, in this peaceful corner of the world he represented the omnipresence and the omniagitation[35] of European industry. Before that, he had represented many other things. During his youth he had served in Russia in the cadre of a regiment; a general's aide-de-camp, he had acquired a bit of a reputation in the smart society of Moscow. Then leaving his epaulets behind, he had set out for Constantinople, where politics got the better of him. Praised by some, denigrated by others, he had painfully threaded his way through a good many adventures, and after enough long years of intrigues, he had been seen doing business in Alexandria. There he had contacted merchants who had taken him to the Indies. The profits from the voyage had probably been thin, for Count Mella returned to his country with a very modest retinue, and settled down in the Peloponnesus, where he spent a few years. Meanwhile he had aged; the seventy or so years ringing in his ear told him to be wise. He took advantage of the advice and married a very young woman, and after two years of the blessed state, he had come to Antiparos to try his fortune once more. Thus, a Russian officer, a Turkish or Greek politician, Egyptian merchant, and Indian courtier in succession, the Ionian count now found himself a winegrower in the Cyclades. One cannot refuse to give this type, which is not at all rare in the Orient, credit for its amazing activ-

ity, ingeniousness, adaptability and philosophy in the face of adverse fortune.

Norton saw the islander at some distance walking toward the arriving guests; at least he assumed, and with some reason, that on the whole island of Antiparos, the description given by the two Naxiotes could fit only the person walking at that moment at the other end of the path. The Count was a man of average size, poorly clothed, though not unpretentiously, who did not look so old as M. Phrangopoulo had said. He behaved very hospitably, took the group from the Aurora to his house, which was built in the midst of rocks, pointed out for their admiration four pitiful six-foot-high trees that formed a hedge in front of the house, and that could not fail to grow some day and even to bear leaves, if only the wind would grant them life; he showed with a mysterious and self-satisfied air a half-dozen horribly mutilated fragments of marble he had discovered while laying the foundations of his house, and launched into a long description of the ancient masterpieces he had no doubt he would unearth some day.[36] Meanwhile, he had only very poor fragments from the worst period. The famous discovery of the statue found on the island of Milo in 1821[37] had become the favorite legend in the Cyclades, and there is not in the whole archipelago a rock pile so small that it does not make inhabitants dream of the exhumation of some Venus in the near future.

Antiparos is not a large island; it boasts, however, a few fishermen's huts and even a village; but that is not where its attraction lies. Count Mella advised his guests to avail themselves of this excellent occasion to visit the famous cave[38] situated at the summit of the island. All the officers displayed great enthusiasm for the expedition; and Norton, delighted by the prospect of roaming about the countryside in Akrivie's company, eagerly acquiesced to the wish of the others. They sent back to the ship for more men, for ropes, ladders, and torches, and they were on their way.

No Greek island is so absolutely barren that it does not have some greenery inland, and, like beautiful girls for whom the slightest ornament is enough, the smallest bush suddenly gives an inimitable grace to this or that corner of the landscape. The region they were going through in their excursion was extremely hilly; it still consisted of large masses of white marble, here specked with black, there tinted with a rusty color that became an almost vivid orange. In hollows where topsoil had painfully been able to form, thorny shrubs twisted their gray branches bristling with thin, pale, spear-shaped leaves; along the ravines, filled in winter with angry and tumultuous torrents but where at that time not a drop remained, beautiful, luxuriant oleanders grew in thick clumps; still this lushness revealed itself only to those who took the trouble to look for it, just as glory is not found on easy paths. Charles Scott, the Scottish middy, managed, however, to pick two bunches of flowers. Blushing to his ears, he offered the first to Akrivie while they were going through a narrow gorge where he hoped no one could see them; as for the second, she found it that evening at her bedside, the culprit having given it to Thompson with the dreadful lie that the young lady had picked it herself and that he had agreed to carry it for her. So that during that day Akrivie made two suitors and a crowd of admirers among the Aurora 's officers. Norton saw that he had a rival, but he did not mind. Far from begrudging it, he felt his former sympathy increase for the bold youth, who had all along been his protégé. Charles Scott's mother, the penniless widow of a clergyman, had two children, an elder daughter Effie, more or less Akrivie's age, and Charles. Raising him and getting him into the navy had required a sustained effort and long resignation to much drudgery. Charles knew it not only as a fact, but in his heart; and living for his mother and sister was his main motivation and a goal ever-present in his thoughts. He had no other ambition than to succeed in making life as good as possible for

these two cherished beings. There was no mansion that he would not examine with a critical eye and promise himself to buy if it was good enough to house his idols one day. He did not think of himself as repaying a debt, he simply wanted to give them everything. As for himself, he was determined not to marry in order to make Effie's children his only care once she had married the youngest, the handsomest, the richest of the members of the House of Lords. To tell the truth, Akrivie had just impressed him in a way that changed all that; but he found that the young Naxiote resembled Effie. Norton guessed as much and said to the young man:

"Scott, don't you think that this young person reminds one of Effie?

— Oh! yes, Sir," answered the middy, blushing to his ears.

Things would have proceeded in this jolly way if during the excursion another middy had not indulged in a few audacious jokes about his comrade's preoccupation. The result was a boxing match, with Charles the aggressor, and he put so much hot anger into his punches that they had to tear his unfortunate adversary out of his grasp, his two eyes blackened and his mouth bloody. The doctor, the only one in on the secret of this row, which they were able to hide from the first officer, made the judicious remark while bathing the victim's face, that wherever Venus showed herself, Mars was never far behind. The old doctor was a damnable classicist; but he nevertheless told the awesome second without batting an eye that this awkward George Sharp had fallen on some stones.

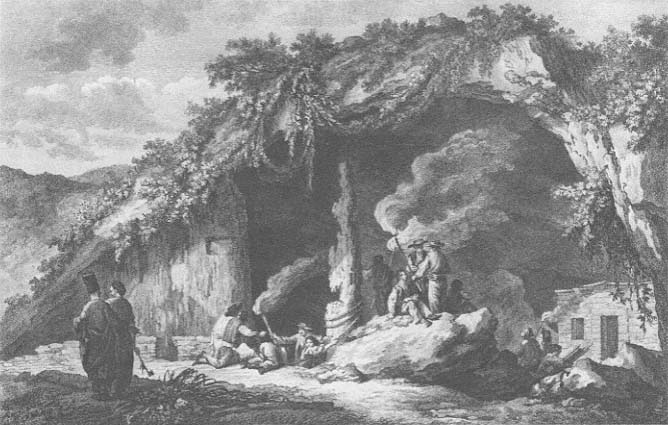

Meanwhile, they had reached the highest point on the island, and the cave opening, already glimpsed from the foot of the previous rise, displayed itself in its full majesty to the gaze of the visitors gathered under its arch. Nature had carved out of solid marble this immense dome whose depth one does not suspect largely because of its height. Ropes

Entrée de La Grotte d'Antiparos

were prepared, the torches lighted, and the sailors, unrivaled in the world for this kind of expedition, began to prepare the descent under the expert supervision of one of the lieutenants who knew the place.

If forced to, one can understand that geologists or naturalists, who claim expertise in these matters and who are professionally trained to see light in black holes, are permitted to descend into such godforsaken places; but the rest of mankind has no business there.[39] Scientists hope to find there some booty; and if they break a neck or limb, it does not seem utterly ridiculous, though one cannot say the same about their ignorant imitators. To descend into the Antiparos cave, you have to squeeze foxlike through one of the narrow tunnels that open at the end, right and left of the main entrance. You enter an opaque darkness bent over so as not to break your head against the rock above you. You drag along painfully and in the most absurd position over a sweating and slippery rock, and you grab the end of a rope. You hang onto it and let yourself slide, which works tolerably well as long as the surface you are moving along slopes downward; all of a sudden it angles inward and then, with the hand not holding the rope, you cling to the crags, trying not to fall into you do not know what since you cannot see a thing. So much for the first chapter; this fun stops when you feel ground under your feet. Do not, however, rejoice prematurely; you are on a narrow cornice and should get off it as soon as possible. The second chapter is about to start and, drawing the torch to you and leaning against the wall along which you have just been sliding, you arrive at an opening where a rope ladder is attached. You can see the top of it, but nothing below as it is a black and gaping void; no amount of light could possibly make you see more of it, for your eyes have not yet had time to adjust from the dilation normal in the sunlight where you were only a moment before.