III

The Question of Authenticity

Scholars contesting the authenticity of On the Jews have put forward more than a dozen different arguments. Some fail to prove the case. For example, the facts that Hecataeus was credited with the forged book On Abraham and that Philo of Byblos had doubted whether Hecataeus wrote the treatise On the Jews only illustrate the general problem, but cannot be used as evidence.[1] The enthusiastic description of the Jewish people was, as one might expect, also introduced as an argument against authenticity, but this was rejected in light of certain general parallels to idealized accounts of oriental peoples known from Hellenistic ethnographical literature, and the description of the Jews as "philosophers" by early Hellenistic authors.[2] The evident idealization of Mosaic Judaism in Strabo's ethnographical excursus (XVI.2.36-39) is even more relevant here.[3] Two other arguments, based on a sentence ascribed to Hecataeus by Pseudo-Aristeas (31) and a reference to the Jewish tithes in one of the fragments (Jos. Ap. I.188), are by themselves inconclusive and have been rightly rejected.[4] It has also been pointed out that there is no quotation from the book ascribed to Hecataeus in the collection of Hellenistic writings on the Jews compiled by Alexander

[1] See Lewy (1932) 118-19; Guttman (1958-63) I.66-67; M. Stern (1974-84) I.23; Holladay (1983) 280-82; Goodman in Schürer et al. (1973-86) III.672-73.

[2] See esp. Lewy (1932) 118; Gager (1969) 131-34. On the Jews, see Theophrastus ap. Porphyr. Abst. II.26; Megasthenes ap. Clem. Strom. I.15; Clearchus ap. Jos. Ap. I.179.

[3] On this excursus and its origin, see further pp. 212-13 below.

[4] See pp. 140ff., 159-60 below.

Polyhistor (first century B.C. ), but this argument from silence is even less significant for the debate.[5]

The difference in general tone and attitude toward the Jews between the treatise and Hecataeus's Jewish excursus in the Egyptian ethnography, as well as the contradictory references to the priests' income (Diod. XL.3.7, Jos. Ap. I.188), deserves more attention. It has been argued in defense that On the Jews was written by Hecataeus at a later date, after he had become better acquainted with Jews and Judaism, or had made a special study in preparation for his treatise on the Jews.[6] Unfortunately these assumptions can be neither proved nor disproved: if On the Jews is authentic, it must have been written after the battle of Gaza (312 B.C. ), which is explicitly mentioned (Ap. I.184, 186), and before the final reconquest of Judea by Ptolemy I (302 B.C. ), in which the king treated the Jews harshly and deported many of them to Egypt.[7] As far as Hecataeus's Egyptian ethnography is concerned, it seems to have been written between 305 and 302.[8] There is thus still some room for dating the composition of the Jewish excursus earlier than the Jewish treatise.

The positive evidence brought forward so far to support authenticity is quite meager It has been argued that the author must have been a gentile, since, while demonstrating an apparently thorough acquaintance with Greek culture, he seems to make a basic mistake concerning the Jewish deportation to Babylonia (Ap. I.194). This, however, could well be expected of a Hellenized Jew; we know of such cases in Jewish Hellenistic literature. But, as a matter of fact, the statement about the deportation has already been shown to be reliable,[9] and a close examination of the passages proves that the author had only a partial and inaccurate knowledge of Greek heritage and practices.[10]

On the other hand, a number of arguments against authenticity based on a historical analysis of statements in the fragments themselves still seem in principle to be valid. All of them were mentioned in one way or

[5] Contrary to the opinions of Graetz (1876) 344; Willrich (1900) 111; cf. Schaller (1963) 27-28.

[6] See esp. M. Stern (1974-84) I.24, and there also other explanations.

[7] See the sources and discussion, pp. 71-77 below.

[8] See pp. 15-16 above.

[9] See pp. 143-44 below.

[10] See below, pp. 148-59.

another by Willrich in his Judaica (1900), and have since been repeated or elaborated on by other scholars. Nevertheless, the analysis has not always been sufficiently convincing and has also frequently been accompanied, especially in the case of Willrich, by mistaken assumptions and inexactitude. The older arguments, therefore, need far more evidence and elucidation. It is also necessary to scrutinize the counterarguments and solutions offered by the proponents of authenticity.

In discussing the various passages, the following considerations will concern us:

1. Do the views expressed or implied in the passages accord with the conceptions and convictions of Hecataeus?

2. Are the data about Greek practices incorporated in the treatise confirmed by extant knowledge, meaning that they could have been written by Hecataeus?

3. In view of his position in the court, Hecataeus must have been acquainted with, or striven to know, the truth about certain details relating to the Jews (e.g., information having a military significance, Jewish leadership, and the like); can these be verified? We may observe that had Hecataeus not served in the Ptolemaic court, and had he actually resided on the Greek mainland, as one scholar (unjustifiably) maintains,[11] the whole issue of authenticity would have been decided at the outset: Hecataeus's position in the Ptolemaic court is emphasized in the passages (in addition to Josephus's introductory notes).

4. Does the presentation of major events that took place in the time of Hecataeus agree with hard evidence from other sources concerning that time? And if not, could it be that Hecataeus was interested in distorting the real facts?

5. Could all the described historical events and developments relating to Jewish history have taken place before or during the lifetime of Hecataeus?

Unfortunately, a stylistic comparison with Hecataeus's Egyptian ethnography and the Jewish excursus would not be of much help: Diodorus's involvement in shaping the vocabulary and style of the epitome was too great to allow a reliable basis for comparison.[12] One should also be cautious in applying arguments from silence and the like.

[11] See p. 8 n. 2 above.

[12] See p. 24 and n. 49 above.

Thus the absence from the passages of any reference to Moses as well as of philosophical and social reasonings, which are so predominant in the excursus, may support the claim of forgery, but can be used only as a second line of evidence. On the other hand, caution should also be exercised regarding the detailed and astonishingly accurate knowledge of the Temple and its cult objects demonstrated by the author, which in itself need not necessarily indicate that he was Jewish.

The discussion of this chapter will examine one by one the passages that have appeared suspect to previous scholars, and two additional fragments that have been virtually neglected in the scholarly debate but furnish new evidence. These are Ap. I.195-99 and 201-4, containing the geographical account of Judea and Jerusalem, and the Mosollamus story (see sections III.1, 8). We shall keep to the order of the passages as they appear in Against Apion, with one exception, the Mosollamus story: though it is the last of the fragments quoted in the first book of Against Apion (201-4), it will be placed at the start of the discussion. Being the most complete and comprehensive fragment, it provides a wider range of considerations for evaluating the question of authenticity.

1. Mosollamus the Jew and Bird Omens

The author claims to have participated personally in a Ptolemaic military march to the Red Sea, and to be recording an event that took place in the course of the advance. Among the Jewish horsemen who took part in the expedition there was a certain archer, called Mosollamus. He is described as a man with a robust mind and "as agreed by all, the best archer among the Greeks and barbarians" (Ap. I.201). At a certain point, the whole force halted because a bird was seen flying about nearby and the seer (mantis ) wanted to observe its motions. When Mosollamus inquired as to the reason for the halt, the seer pointed to the bird and explained the rules of interpretation (I.203):

If it [the bird] stays there, it is expedient for all to wait still longer, and if it rises and flies ahead, to advance, but if [it flies] behind, to withdraw at once.

Then Mosollamus, without uttering a word, shot and killed the bird. When the angry seer and certain others cursed him, he took the bird in his hand and retorted (I.204):

How, then, could this [bird], which did not provide for its own safety, say anything sound about our march? For had it been able to know the future, it would not have come to this place, fearing that Mosollamus the Jew would draw his bow and kill it.

The episode already seemed questionable to Philo of Byblos. According to Origen, Philo doubted the authenticity of the book because it stressed the "wisdom" of the Jews (C. Cels. I.15). Philo was certainly referring to the Mosollamus story, and most probably also to other pieces of information, which were not preserved by Josephus.[13] The description of the wise Jew who mocks the foolish, superstitious gentiles also convinced some modern scholars that the story was written by a Jew.[14] This, however, is still not enough to establish a forgery.[15]

Other scholars have argued, to the contrary, that the scornful attitude toward omens accords with that of "contemporary educated Greeks" and may therefore represent Hecataeus's own views.[16] The available evidence does not, however, justify such a sweeping statement. To say that educated Greeks had a negative attitude toward omens is an exaggerated generalization, even more so than the rhetorical statement of the supporters of divination in the Ciceronian dialogue that divination had been "the unwavering belief of all ages, the greatest philosophers, the poets, the wisest men, the builders of cities, the founders of republics" (Div. I.84; cf. 5, 86).[17] In any case, the main question is not whether an educated Greek would have praised the negative Jewish attitude toward gentile divination and bird omens, but what Hecataeus's personal view was.

[13] See the discussion, p. 184 below.

[14] Geffcken (1907) xv; Jacoby, RES.V. "Hekataios (4)," 2766-67; Reinach (1930) 39; Rappaport (1965) 142-43; Hengel (1971) 303.

[15] The only attempt so far to reach a conclusion on the question of authenticity by referring to the details of the story is a short note by W. Burkert in Hengel (1971) 324. However, it could not possibly decide the issue. See the comments in nn. 41 and 50 below.

[16] J.G. Müiller (1877) 177-78; Lewy (1932) 128-29; Holladay (1983) 333-34 nn. 51-52. See also p. 64 below on the episode in the letter attributed to Diogenes.

[17] See the discussions and summaries of Wachsmuth (1860); Bouché-Leclercq (1879-82) I.14ff.; Nilsson (1940) 121-39; Cumont (1960) 57ff.; Flacelière (1961) 103-18; Pease (1963) 75, 206-9, 312; Nock (1972) II.534-50; Pfeffer (1975); Pritchett (1974-91) III.48-49, 141-53.

The tradition about the affiliation of Hecataeus with the disciples and "successors" of Pyrrho (Diog. Laert. IX.69), if accepted, could have provided a clue as to Hecataeus's position: certain contemporary testimonia about Pyrrho indicate at least a tolerant, if not a favorable, attitude toward religious ceremonies and divination.[18] However, this tradition is rather doubtful.[19] Hecataeus's stand with regard to divination should therefore be deduced only from his ethnographical works.

The surviving material does not contain a thematic discussion of the reliability of divination and bird omens. There are, however, quite a number of relevant references. In his Egyptian ethnography, preserved by Diodorus in an abridged version,[20] Hecataeus refers more than a dozen times to Egyptian and Greek divination in a generally positive way. Hecataeus mentions incubation in temples (Diod I.25.3, 53.8), oracles (23.5, 25.7, 66.10; cf. 98.5), inspection of the entrails of sacrifices (53.8, 70.9), dream interpretation (65.5-7), divination in general (73.4), and astrology (73.4, 81.4-6, 98.3-4). One passage reports that hawks and eagles were regarded by the Egyptians as "birds of omen" (87.7-9).[21] Most of the allusions are preceded, as customarily throughout his Egyptian ethnography, by such phrases as "they say" (

[18] The relevant sources: Eus. PE XIV.18.26 (Pyrrho preparing a sacrifice for his sister); ibid. 24 (Pyrrho's real or alleged visit to Delphi or Oropus to consult the oracle; see Long [1978] 73-74); Diog. Laert. IX.64 and Hesychius of Miletus FHG IV.174 (Pyrrho being appointed high priest). The first two references evidently drew on testimonia from the time of Pyrrho (Antigonus of Carystus and Timon via Aristocles), and the same may be true of the third one (Antigonus of Carystus?). Sext. Emp. Pyrrh. I.17 ("to live according to the traditional customs and laws") reflects the later Skeptical tradition.

[19] See p. 8 n. 5 above.

[20] On Hecataeus and Diodorus's Egyptian ethnography, see in detail P. 14ff. and esp. Extended Notes, n. 1 p. 289. The narrative material and comments quoted below are definitely Hecataean and not additions by Diodorus (see nn. 21, 22 below).

[21] There is no involvement of Diodorus in the contents of the passage, which is part of the rationalization and praise of the Egyptian animal cult; see below p. 99 n. 138 referring to Diod. I.83.8. Porphyry mentions only the hawk as an Egyptian bird of omen (Abst. IV.9). He may have drawn on Hecataeus. See further nn. 33 and 53 below.

of an oracle recorded by Herodotus (66.10; cf. Hdt. II.151ff.). His criticism in this case stems not from a rejection in principle of oracles, but from the evident improbability of the story (the circumstances of the rise of Psammeticus to sole rule in Egypt; cf. Diod. I.69.7). On another occasion he even states that the Egyptian sources support their statements with facts, unlike the Greeks, who rely on legends (25.3). There are no reservations with regard to the other references, although Hecataeus does not refrain from criticizing his Egyptian sources when he finds their accounts unreliable (e.g., 23.2; 24.2, 5; 25.2-3). One story recounted by him about divination does not mention sources, and the information given is recorded as objective fact (65.5-7). Above all, Hecataeus precedes three other allusions to divination and astrology (73.4, 81.4-6, 98.3-4) with the statement that he refrained from quoting imaginary tales by Herodotus and other Greek authors, and selected from the records of the Egyptian priests only information "that passed our scrupulous examination" (69.7).[22]

When evaluating this material, it should also be borne in mind that Hecataeus's Egyptian ethnography is, to a great extent, an idealization of Egyptian life and practices.[23] It is therefore hardly credible that the same author would reject or even ridicule pagan divination techniques. The same conclusion is also suggested by Hecataeus's highly tolerant and sympathetic treatment of religious beliefs in the Egyptian ethnography. He even goes so far as to provide explanations for and make favorable comments on the animal cult,[24] which was regarded by the Greeks and Romans as bizarre and contemptible.[25]

Examination of the few fragments of Hecataeus's utopian On the Hyperboreans supports this conclusion.[26] The god Apollo plays a central role in the treatise (as in almost all other literary references to

[22] The last reference, as well as para. 25.3, mentioned above, which are decisive for the argument, undoubtedly originate in Hecataeus's work. The same applies to the criticism of Herodotus on Egypt. It is agreed that Diodorus did not usually bother to consult more than one source for a single subject, certainly not for minute details, and that he did not indulge in source criticism.

[23] See pp. 16-17 above.

[24] See pp. 98-99 below.

[25] See the sources on p. 98 n. 137 below.

[26] On this book as affecting Hecataeus's social, political, and religious ideals, see, e.g., Susemihl (1891) I.314; Jacoby, RES.V. "Hekataios (4)," 2755; id. (1943) 52ff.; Guttman (1958-63) I.42-45.

the Hyperboreans).[27] Although the material at our disposal elaborates only on his contribution (and that of his cult) to the musical life of the Hyperboreans (Diod. II.47.6; Aelian, Nat. Anim. XI.1), one may assume that Apollo's second main role, as god of divination, was not neglected. Furthermore, Hecataeus enthusiastically describes the regular arrival of "clouds of swans" from afar at the time of the services in the Hyperborean temple. They always join the chorus chanting hymns in honor of Apollo. All is performed in perfect harmony (Ael. NA XI.1):[28]

Never once do they sing a discordant note or out of tune, but as though they had been given the key by the leader they chant in unison with the natives, who are skilled in the sacred melodies.

That nothing in their behavior is accidental attests to divine inspiration. Hecataeus accordingly accepted the belief that swans were Apollo's sacred birds and messengers,[29] and in Greek tradition this also entailed prophetic as well as musical gifts.[30]

This survey of Hecataeus's direct and indirect references to the techniques of ancient mantics, as well as his attitude toward Egyptian cults (including those viewed by the Greeks as superstitious), seems to suggest that Hecataeus could not have written a derogatory story about bird omens. And it cannot be argued that the author merely quotes the view of Mosollamus the Jew. He clearly enjoys telling the story, without reservation, and praises Mosollamus's "robust mind." The story was probably understood in a similar manner by Herennius Philo, who, therefore, suspected the authenticity of the treatise.

Analysis of the various details of the Mosollamus story further shows that it was not written by a knowledgeable Greek, certainly not by an author of the caliber of Hecataeus. The story either lacks or distorts all the basic facts about Greek bird divination. And it must be recalled that the author presents himself as an eyewitness (Ap. I.200). But before any discussion of the details, an important clarification must be made. It might be argued that the episode is just a joke, and that, consequently, the author was not concerned with accuracy and even deliberately distorted all technical details. This, however, can

[27] See Bolton (1962) 22ff., 106ff., et passim.

[28] The translation: Scholfield (1958-59) II.357-59 (LCL ).

[29] See the sources in Pollard (1977) 145-46 and 195 n. 59.

[30] See esp. Plato, Phaedo 84b; Arist. HA IX.615 2.

be expected of a satire, not of a story—even if it is told as a joke—the whole purpose of which is "to point a moral, or adorn a tale." The last paragraph (204) points the moral. Had the real Hecataeus distorted all the basic facts, he would have spoiled the whole didactic impact of the story. An author who knew his facts would not have done this.[31] Besides, the surviving material of Hecataeus's works (and there is enough of it to judge) does not show any traces of satiric writing.

When we turn to the Mosollamus story, the first conspicuous fact is that the episode does not accord with the Greek theological conception underlying bird omens. Mosollamus says that had the bird indeed been able to "know the future" (

He [Socrates] was introducing nothing newer than were those believers in divination who rely on bird omens, oracles, coincidences, and sacrifices. For they do not believe that the birds or those met by accident know what will happen to the inquirer, but that the gods indicate what will happen to him through them.

The same explanation for omens, sometimes with specific reference to birds, is known from quite a number of sources.[33] This understanding

[31] Two stories, which might appear to be similar to the Mosollamus episode, an Aesopean fable (no. 170 ed. Hausrath [Leipzig, 1970]) and a tale about Diogenes of Sinope (EG, Diog. no. 38 [p. 253]), ridicule streetcorner soothsayers who were not able to foresee their own troubles. The authors do not record the technicalities of divination, since they were not necessary for the moral. What matters for the present discussion is that they do not distort the basic facts. For the difference in motifs between these two stories and the Mosollamus episode, see pp. 64-65 below.

[32] The vulgar opinion is recorded by Philo, Spec. Leg. I.60-63, who explicitly relates it to the "mob" (para. 60).

[33] Xen. Hipp. IX.8-9, Cyr. I.6.1; Plut. Dion 24; Sollert. Anim. 975A-B; Sen. NQ II.32.3ff.; Orig. C. Cels. IV. 88; Amm. Marc. XXI.1.9; cf., e.g., Cic. Div. I.118-19, II.35-39 on the Stoic doctrine of the divination of entrails. Two later sources of the Roman period attribute "understanding" to birds: Pliny states that of all birds, only ravens are able to understand the meaning of the omens they convey (NH X.33), while Porphyry attributes this ability to "all mantic birds" (Abst. III.5.3). This, however, does not contradict the former sources: certain birds understand the omen themselves, but this does not mean that they know anything beyond the specific event referred to by the omen. The omen in the Mosollamus story applies only to the question of whether or not to continue the march. The relevance of Porphyry, an author of the third century A.D. with strong mystical inclinations, to the accepted view of educated Greeks in the fourth century B.C. is by itself highly doubtful. (One cannot determine the source of his statement, though in the same passage he clearly uses Roman sources.) Pliny for his part stresses that only ravens are gifted with "understanding." It should also be noted that whooper swans, which in addition to being "mantic birds" were believed to know (and sing) when they were about to die (Ael. NA V.34, X.36), are an exceptional case described as such. Yet this faculty can be regarded as activated instinctively at the onset of a natural death only, and not by the prospect of an unexpected, sudden death, as in the case of the bird in the Mosollamus story.

gave rise to a number of theological problems. Cicero thus records the deliberations of the Stoics (Div. I.118):[34]

But it seems necessary to determine the way [by which these signs are given]. For the Stoics do not believe that god is involved in every fissure of the liver or in every song of a bird; quite obviously that would be neither seemly nor proper for a god and furthermore would be impossible. But, in the beginning, the world was so created that certain results would be preceded by certain signs, which are given sometimes by entrails and by birds, sometimes by lightning, by portents and by stars, sometimes by dreams, and sometimes by utterances of persons in a frenzy.

The philosophers who rejected belief in omens did not ignore these explanations. Some even tried to refute them point by point. Thus Cicero, in the second book of a long dialogue, examined all aspects of contemporary divination.[35] Others expressed their negative view

[34] The translation: Falconer (1923) 351-55 (LCL ), with a number of changes. Cf. Sen. NQ II.32.3-4.

[35] See especially the direct philosophical arguments against bird divination in Div. II.16, 53, 56-57, 76, 80, 82-83, and, indirectly, 9ff., 18-21, 25. Cf. 30, 36, which actually could also be used against bird omens.

inter alia by short notes, like the rhetorical question of Carneades and Panaetius preserved by Cicero (Div. I.12):[36]

Therefore let Carneades cease to press the question, which Panaetius also used to urge, whether Jupiter had ordered the crow to croak on the left side and the raven on the right.

Even in this rather cynical remark, the question is not whether the bird "knows" or not, but whether the deity reveals his will to mankind in this way.[37] The Mosollamus story, however, does not indicate any familiarity with the accepted Greek conception of bird omens. It has already been explained above why it cannot be argued that Hecataeus simply recorded the Jewish perception.

In this context it would be worth referring to two Greek anecdotes that carry a seemingly similar lesson. Hans Lewy compared the Mosollamus episode with a story in one of the spurious letters attributed to Diogenes of Sinope. The letter relates how, at the time of the Olympic games, Diogenes ridiculed a seer (mantis: either an ecstatic prophet or a soothsayer who interprets signs or dreams). Diogenes lifted his stick and asked the man whether he would strike him or not. When the seer answered in the negative, Diogenes, much to the amusement of the bystanders, struck him with his stick.[38] The same motif appears in a fable related by Aesop: a mantis who earned his living from prophesying in the market was alarmed by the news that his house had been broken into. A passerby rebuked him, saying: "While announcing that you knew beforehand the affairs of others, you did not predict your own" (no. 170, ed. A. Hausrath [Leipzig, 1970]).

There is, however, an essential difference between the Mosollamus episode and the two anecdotes: Mosollamus ridicules the "foreknowledge" of the bird; that is, he denies the capability of the mantic "instrument" itself to know the future. However, Greeks did not need to challenge this. The two anecdotes, on the other hand, mock the ability of a dilettante to foretell the future or interpret signs. The argument

[36] See also Div. I.85; II.56, 72, 80. For a somewhat similar line of argumentation with regard to another subject, cf. Philo, De Mutatione Norninurn 61; Quaest. et Solut. in Genesim II.79.

[37] On the question of Panaetius's attitude toward divination, see the summary and bibliography by Pease (1963) 62-63, and p. 64 on Carneades.

[38] Lewy (1932) 129 and n. 4. The letter: EG, Diog. no. 38 (p. 253).

is quite different, and was frequently employed against quack prophets, especially streetcorner soothsayers.[39]

No less instructive than the theological conception are both the terminology of the story and the mantic techniques described by the gentile seer himself. The very reliance on bird omens for military purposes is indeed known not only from the history of the Roman army and from other cultures, but is also found in Greek tradition,[40] although it did not take the form of regular, systematic ornithoscopy, but rather of the interpretation of the chance appearance of certain less common birds.[41] Such bird omens were occasionally encountered by armies in the course of their expeditions.[42] So far there is nothing exceptional in the Mosollamus story. However, when the minute technical details are reviewed, one finds it difficult to believe that the story was written

[39] See, e.g., Cic. Div. II.9ff.; Jos. Ap. I.258; Luc. Deor. Dial. 16.1 (244). Without referring to the attitude toward divination of Diogenes himself, it is noteworthy that Plutarch, who has a favorable opinion of portents and omens (see, e.g., n. 33 above; cf. Nock [1972] II.538ff.), deplores streetcorner soothsayers (Pyth. Orac. 407C, Cic. 17.5, Lycurg. 9.5).

[40] See the latest collections of material in Pollard (1977) 116-29; Pritchett (1974-91) III.101ff.

[41] W. Burkert (in Hengel [1971] 324) argues that the story could not have been written by Hecataeus, since military ornithomantics was not practiced in the Hellenistic period. This is to overlook the fact that the Mosollamus story, whether genuine or not, was in any case composed during the Hellenistic period, indicating that the interpretation of bird omens still was resorted to by armies when a "mantic bird" was observed. Moreover, ornithoscopy was well known and practiced in the Hellenistic period (see some of the sources nn. 48, 49 below), and the disappearance of bird mantics from the Hellenistic battlefields in a period when Greco-Macedonian troops were confronting Roman armies, which adhered so much to their own auguric traditions, is by itself implausible. Polybius's negative attitude toward omens and portents (see esp. VI.56.6-12, IX.19.1, XXXIII.17.2) is chiefly responsible for the absence of references to bird omens in extant accounts of Hellenistic battles, most of which are derived (directly or indirectly) from his version. Burkert seems also to be inaccurate in stating that the inspection of entrails for military purposes was declining. See, e.g., Polyaenus IV.20 and Onasander X.24. Plut. Aem. 19.4 and Polyb. V.24.9, XXIII.10.17 may also be taken to indicate sacrifice divination. Be that as it may, bird divination could not have disappeared as early as the beginning of the Hellenistic period.

[42] E.g., Il. I.168-84, VII.247ff., X.274ff., XII.195-250, XIII.822, XXIV.315; Xen. Anab. VI.1.23, 5.2; Plut. Them. 12; Cic. Div. I.74, 87. Onasander X.26 ("signs of sight and sound") may also hint at bird omens.

by a Greek. Curiously enough, the author does not specify the bird, although the general term ornis is repeated four times, and the story is devoted to bird divination.[43] The Greeks regarded some ten or twelve species as birds of omen, but others were excluded.[44] In the words of the poet: "Many birds fly to and fro under the sun's rays, but not all are [birds] of omen" (Od. II.181). When it came to military affairs, the usual birds of omen were the eagle, Zeus's sacred bird and "the surest bird of augury" (Il. VIII.247),[45] the hawk, consecrated to Apollo (Ael. NA VII.9, X.14, XII.4), and occasionally (especially for Athenian troops) the owl.[46] Hecataeus himself elaborates in his Egyptian ethnography on the hawk and eagle as birds of omen (Diod. I.87.7-9). The absence of any specification and the repetition of the word ornis indicate, therefore, a lack of exact knowledge about Greek practice. Furthermore, the author does not use the term oionos even once, although it is the more common designation for a bird of omen.

It may be responded that the author wishes to stress that the soothsayer's source of information was just a bird. But one would expect an author—who claims to be an eyewitness—to specify at least once the exact bird he saw; a specific reference to an eagle or a hawk would only have strengthened the didactic effect of the story. Had Mosollamus been able to shoot such a bird, well known for speed, this would have emphasized the whole point of the story. The author would then still have had a few opportunities to express the idea that the bird was just a bird.

As for the rules of interpretation: like the Roman augurs, Greek diviners also had a disciplina auguralis, a set of rules for the interpretation of omens, which differed slightly from place to place. It was a rather complicated "science," the rules defining the meaning of a variety

[43] The use of just the word ornis in incidental or one-time references to birds of omen is not exceptional. See, e.g., Il. XIII.821; Od. X.242; Hesiod, Erg. 828; Aesch. SCT 26, Agarn. 112; Soph. OT 52; Eur. Phoen. 839; Aristoph. Birds 719. However, the only subject of the Mosollamus story is bird omens, and the word is mentioned more than once.

[44] See Holliday (1911) 270; Pollard (1977) 120, 126-27.

[45] Cf. Cic. Div. II.76; Sen. NQ II.32.5.

[46] See Pritchett (1974-91) III.101ff., 105ff. Add Diod. XXII.3 for owls. The carnivorous bird or raven mentioned in Arr. Anab. II.26.4-27 and Curt. IV.6.12 is an exception. The nature of the occurrence (the bird dropped a stone on Alexander's head while he was making a sacrifice) could not but be taken as a warning.

of movements and their combinations. Thus an inscription found in Ephesus, from the time of the Persian Wars, which contains a sacred law code, elaborates on the meaning of bird movements (SIG[3] 1167):

[(If) the bird is flying from right to left:] if it disappears—fortunate. But if it raises the left wing: whether it (only) rises or disappears—ill. And (if) it is flying from left to right: if it disappears in a straight (course)—ill, but if after raising the right wing—[fortunate] ...

These were not all the rules. The code is only partially preserved, and the complete set must have made decision rather difficult. The seer had thus to set in order and balance conflicting signs and rules. The Ephesian code may indeed represent only a local tradition, as some scholars maintain,[47] but there is no doubt that the overall rules applied in the Greek world were quite complicated, as can be deduced from a fair number of sources.[48]

Then again, the very clarification of the basic facts demanded much effort. Even the simplest question, common throughout the Greek world, whether the bird came from the right or the left, was not easy to establish. The flight of an eagle or a hawk near an army usually came as a surprise and happened very quickly. The reports on the direction of the arrival were consequently often contradictory, and whatever evidence there was had to be sorted out and clarified by the seer In

[47] See Wilamowitz (1931) I.145; Pollard (1977) 121; and the opposite view by Holliday (1911) 269 n. 4; Pritchett (1974-91) III.103-4.

this context there was also the question of defining and determining right and left. If this was to be resolved in relation to the direction faced by the seer himself, the problem arose as to how the latter could be sure of his own exact position at the moment of the bird's arrival. And if it was accepted that the seer always faced the residence of the gods, was that north or east? Or was there perhaps another rule, referring, for instance, to the general direction of the army's advance? The knowledge and experience of a professional seer were thus indispensable.[49] But this was just the beginning. The remaining considerations relating to the bird's overall motions and more particular details could give rise to even greater uncertainties. And there was still the necessity of balancing all the different and complicated instructions.

The seer of the Mosollamus story, however, refers to just three basic positions: flight forward, retreat, and landing. So far as I know, there is no parallel in Greek literature for the application of such rules. These elementary positions could well be regarded as accidental and were therefore discounted as divine signs. Such an interpretation could occur, at most, only to ignorant people unaware of the theological background of bird mantics, not to an official seer, as suggested by the story. In any case, it does not take the expertise of a professional seer to offer this sort of interpretation.[50] On the other hand, there is no reference to the traditional rules accepted by the Greek world, not even to the basic question regarding right and left. We thus see that the author could not have been an eyewitness, nor could he have been a knowledgeable Greek—certainly not one who wanted to win the trust of his Greek readers. Even if one ignores the concluding moral and its necessary effects on the shaping of the story, in order to argue that the intention of the author was to ridicule bird omens at any cost, reference to one

[49] Among the relevant sources, see, e.g., Il. X.274-77, XII.200ff., 237-40, XIII.821, XXIV.315-20; Od. XV.525-26; Plut. Them. 12; Xen. Ahab. VI.1.23; Cic. Div. II.80, 82; Ael. NA I.48; Michael Psellus (see n. 48), lines 30ff. The main discussions: Bouché-Leclercq (1879-82) I.135-38; Jevons (1896) 22-23; Pollard (1977) 121. For Roman practices, see Pease (1963) 76-77, 482, and further bibliography there.

[50] This is what is probably meant by W. Burkert's short, sharp note (without references): "Die Geschichte ... wie der Jude Mosollamus den weissagenden Vogel erschiesst, unterstellt der Vogelschau eine Simplizität, für die es keiner seherischen Kunst bedurft hätte.... Hier wird, ohne Kenntnis yon der Sache, ein Popanz aufgebaut und lächerlich gemacht" (in Hengel [1971] 324).

or two of the real rules (e.g., raising the right or left wing) would have made the episode even more amusing. Thus Philo, wanting to ridicule pagan mantics, refers to reliance on wing motions (Spec. Leg. 1.62).[51] The same appears from the derisive question of Carneades and Panaetius on croaking from right or left. The author's acquaintance with the practice of interpreting bird omens is, then, superficial and vague indeed.[52]

To conclude the discussion: in view of what appears from his writings, Hecataeus's attitude toward bird omens could not have been negative; the punch line of the story betrays the author's unfamiliarity with the theological doctrine of bird divination; the author neither specifies the bird nor uses the proper term for a bird of omen; and he is ignorant of the rules of interpretation, even of the most basic ones current in the Greek world. All these factors make an attribution of the episode to Hecataeus of Abdera virtually untenable.[53]

[51] The passage in paras. 60-62 refers to the vulgar opinion of the mob (cf. n. 32 above).

[52] The only typological parallel I can find for gentile mantics does not relate to bird omens. Lucian of Samosata describes the statue of Atargatis in Syrian Hieropolis, which served as an oracle: the statue is carried by the temple priests, and the high priest presents the question. If the statue drives its carriers forward, the sign is positive; if it forces them to retreat, negative (De Syria Dea 36-37). A similar oracular technique is known from a later temple in Heliopolis (Macr. Sat. I.23.13), and the same may hold for the oracle associated with Alexander's visit to the Ammon temple (Diod. XVII.50-51; see Harmon [1925] IV.392 n.1). The interpretation of such an oracle was based on what were believed to be involuntary movements of the priests, in which a manifest intervention of the deity seemed evident. This was obviously very different from natural, expected, and elementary motions of birds. If this was indeed the former practice in the celebrated Ammon temple, this may suggest a possible source of inspiration for the Mosollamus story. At the same time the "instructions" could also be a product of the author's imagination. After all, it would not take much imagination to invent such an interpretation if the question presented was whether to advance or not.

[53] It might be suggested that the author was actually describing an Egyptian, not a Greek, seer. But this still does not resolve the main difficulties. The very possibility that the Ptolemaic army relied on the interpretation of an Egyptian seer in making important military decisions is by itself rather remote, especially at that early stage in the history of the dynasty (despite the number of Egyptian soldiers and service troops; see Diod. XIX.80.4). It is even less plausible in view of the apparently rare resort to bird omens in ancient Egypt. The only extant reference in the plentiful Egyptian texts (and the numerous references to birds) appears in a "civilian" context in one of the el-Amarna letters. (EA35.26; see Brunner [1977]. Cf. Buchberger [1986] 1047, 1050 n. 23. Brunner's statement that this is the only reference can be trusted, given the encyclopedic knowledge of the Egyptian sources possessed by that prominent Tübingen Egyptologist.) It is surely no accident that this practice does not figure in the numerous Egyptian battle accounts, which contain much information about divination and magic. The references to Egyptian birds of omen by Hecataeus (Diod. I.87.6-9) need not be taken at face value, and may be one of the numerous mistakes and inaccuracies in his Egyptian ethnography, specifically, one of the inaccuracies attributable to (deliberate?) confusion with Greek practices. In any case, Hecataeus does not mention military application. Porphyry (Abst . IV. 9) may have drawn on Hecataeus, or may reflect Hellenistic influence.

In two of the following sections (III.4, 9), I shall refer to explanations offered by the proponents of authenticity for the presence of certain sentences that evidently could not have been written by Hecataeus. These scholars have postulated various ways in which the original text may have subsequently been altered. The validity of the proposed explanations for those passages will be discussed in due course.[54] As far as the Mosollamus story is concerned, they are certainly not applicable. To suggest that the original Hecataean story underwent a "slight" adaptation by an anonymous Jewish author would not resolve the difficulties: a "slight" alteration would not have made all the basic details of the story unreliable. Moreover, Hecataeus had a favorable opinion of Greek mantics; the essence of the story—deriding gentile reliance on omens and divination and praising the wise Jew—could not have been much different in the original. The argument for this interpretation also seems to be supported by the reference of Herennius Philo to Jewish "wisdom." In addition, a Jewish adapter would have had no reason to deviate significantly from the details of the pro-Jewish report; quoting just a few genuine rules of interpretation and specifying the type of bird involved would have been a more effective way of ridiculing gentile divination.

The same arguments also apply against the suggestion that Josephus altered the original text. Furthermore, Josephus twice stresses that he is going to quote Hecataeus (Ap . I.200,

[54] See pp. 100-1 and 120-21 below.

that it is easily available (205). It is hardly possible that Josephus would have repeatedly stressed in this way the authenticity of the passage, even exposing it to comparison, while at the same time significantly diverging from the original text. Given the polemic context, this would have undermined his credibility with the readers. It should also be added that the episode is quoted in direct speech; that the author describes his impressions of the expedition in the first person; and that the story forms a complete and independent literary unit. All these further serve to undermine the possibility of a Josephan adaptation of the original story.

Another recurring explanation for the mistakes in the fragments is that Hecataeus had been misled by Hezekiah the High Priest, who figures in Josephus's quotations (Ap . I.187-89), or by other Jewish sources. This is equally untenable: the author presents himself as an eyewitness, and, in any case, Hecataeus would not have been misled concerning Greek practices, nor would he have been convinced by such sources to change his mind about Greek divination. The only remaining alternative is that the story in its entirety is a Jewish fabrication.

2. Ptolemy I and the Jews

Josephus opens the quotations with the celebrated Hezekiah story (Ap . I. 186-89). Despite the fragmentary transmission of the text, its basic outline can be determined with a high degree of certainty. The background is the period after the battle of Gaza (312 B.C. ) when Ptolemy I became, temporarily, master of Syria. Hezekiah the High Priest and many Jews were so impressed by the "kindliness" and philanthropia of Ptolemy that they decided to emigrate to Egypt. Their purpose was to "take part in the affairs [of the kingdom]." Upon arriving in Egypt, Hezekiah is said to have kept close connections with the Ptolemaic authority and to have served as the leader of the immigrants.[55]

This ideal picture does not accord with the available information on Ptolemy's treatment of the Jews and other nations and cities in his realm. Consequently a number of scholars have doubted the reliability

[55] For a more detailed reconstruction of the contents of paras, 188-89 see pp. 221-25 below. See also pp. 225-26 below for the refutation of the hypothesis that the passage records not an emigration but only a trip to Egypt.

of the Hezekiah story and its attribution to Hecataeus.[56] However, their analyses do not consider all the possibilities, leaving much scope for attempts to harmonize the story with the historical information. In the following pages I shall present the source material and try to clarify the origin of the information, the mutual relationships and reliability of the sources, and the chronology of the events. The conclusions will aid our examination of the story itself.

First, the information about occupied populations in the Ptolemaic realm: according to Diodorus, Ptolemy son of Lagus had in 312 taken severe measures against the native populations in Cyprus and northern Syria. These included the destruction of cities and deportations (Diod. XIX.79.4-6). The inhabitants of Mallus in Cilicia were even sold into slavery, and the region was pillaged (79.6). The concurrent violent struggle in Cyrene (79.1-3) indicates that the occupied population was outraged over its treatment by Ptolemy. As to Coile Syria and Phoenicia, it is reported that immediately after the battle of Gaza Ptolemy won over the Phoenician cities, partly by persuasion, partly by besieging them (85.5). On his retreat a few months later, in 311, he razed the four "most important cities'—Acre, Jaffa, Samaria, and Gaza (93.7). Of the reoccupation of Coile Syria in 302 it is said only that Ptolemy besieged Sidon and that the remaining cities were subjugated, garrisons being stationed in them (XX.113.1-2). In reporting the reoccupation of the cities, Diodorus uses words that imply reluctance, if not resistance, on the part of the local population.

This information can be trusted. It was paraphrased with considerable accuracy by Diodorus from the work of Hieronymus of Cardia.[57] From 317 or 316 on, Hieronymus belonged to the staff of Demetrius,[58] who was operating in Coile Syria and Phoenicia and the surrounding area in 312-311 and reoccupied the region after the withdrawal of Ptolemy. Although at that point Hieronymus served the family of Antigonus, he is known to have been impartial in his writing, and occasionally even criticized Antigonus sharply.[59] The Ptolemaic "satrap

[56] E.g., Willrich (1895) 22-33, (1900) 99-100; Jacoby, RE . s.v. "Hekataios (4)," 2767.

[57] See J. Hornblower (1981) 27-43, 62, and earlier references there. Cf. also Seibert (1983) 2-8.

[58] J. Hornblower (1981) 12.

[59] Ibid. 107ff.

stele" of 312/11 B.C. indeed confirms the general lines of Ptolemy's policy in the occupied territories as reported by Diodorus-Hieronymus.[60] It records, for example, the deportation of soldiers, men, and women from a place whose name is illegible (lines 5-6).[61] The handling of the population in the region by Ptolemy is correctly summarized in Josephus's Antiquities as follows (Ant . XII.3):

The cities suffered ill and lost many of their inhabitants in the struggles, so that Syria at the hands of Ptolemy son of Lagus, then called Soter ["Savior"], suffered the opposite of [what is indicated by] his surname.

These statements may be based on the detailed accounts of the period in the books of Hieronymus of Cardia and Agatharcides, which were well known to Josephus (Ap . I.205-11, 213-14; Ant . XII.5), but the author may also have drawn on an additional source.

Parallel to this explicit information on Ptolemy's harsh treatment of the occupied population, Diodorus provides an especially favorable evaluation of Ptolemy's character, which recalls the enthusiastic account of the Hezekiah story. The term philanthropia is repeated with some variations. Diodorus praises Ptolemy's treatment of the Greco-Macedonian commanders and captives from other Hellenistic armies (Diod. XIX.55.6, 56.1, 85.3, 86.3). The same applies to the measures taken against the native Egyptians at the beginning of his reign (XVIII.14.1) and the Greco-Macedonian immigrants (XVIII.28.5-6). These references have misled some scholars who utilized them to support the statement in the Hezekiah story about Ptolemy I's philanthropia .[62] However, the practical and political considerations behind

[60] See the text in Brugsch (1871) 1-13, 59-61; Sethe (1904) 11-22; Kamal (1905) I.168-71; Roeder (1959) 100-106; Kaplony-Heckel (1985) 613-19. The better-known translation of Bevan (1927) 29ff. is unreliable.

[61] The comprehensive studies of the stele are Wachsmuth (1871), Goedicke (1984), and Winnicki (1991). Preferable to other reconstructions is the suggestion of Wachsmuth and Winnicki that the reference in line 5 is to either Syria or Phoenicia or both. However, Winnicki's hypothesis that line 6 refers to the same region as line 5 is unacceptable, and the identification of the region in line 6 remains anyone's guess. Wachsmuth (1871) 469-70 connects line 5 with Diodorus's report on the destruction of cities in Coile Syria and Phoenicia by Ptolemy I and his transfer of whatever property he could to Egypt (XIX.93.7). This is possible.

[62] See, e.g., Lewy (1932) 121; Guttmann (1958-63) I.67; Doran (1985) 916.

this "philanthropy" toward the Greco-Macedonians are quite obvious, and as far as the Egyptian natives were concerned, Ptolemy's attitude changed after he had consolidated his rule.[63] The handling of the occupied populations outside Egypt was from the start quite different. As a matter of fact, it is doubtful whether contemporary sources applied the epithet philanthropos to Ptolemy I, and it seems to have been supplemented by Diodorus himself.[64] The term was current in Hellenistic Egypt and was one of the main features of ideal monarchy in Hellenistic (and Jewish Hellenistic) literature.[65]

Diodorus does not refer to the policy toward the Jews in the days of Gaza and Ipsus, and Josephus notes in Against Apion that Hieronymus of Cardia did not mention the Jews at all in his work (Ap . I.213-14). Since in that context Josephus strives to prove that the first Hellenistic authors did mention the Jews and deplores Hieronymus's silence, we may well believe that he took the trouble to read Hieronymus's writings with care.[66] We can therefore accept that Diodorus merely followed Hieronymus in his silence about the relations between Ptolemy I and the Jews.

The fate of the Jews is recorded by a number of other sources. They recount severe treatment of the Jews by Ptolemy I. The sources are gentile, Jewish Hellenistic, and Jewish Palestinian. The most detailed of them, Pseudo-Aristeas, states in brief that the land of the Jews was despoiled (23) and elaborates on the deportation of a hundred thousand Jews from Judea to Egypt, the enslavement of many of these, and the stationing of thirty thousand men in fortresses (12, 22-23, 36-37). The second source is Agatharcides of Cnidus, the celebrated geographer and historian who was employed at the Ptolemaic court in the middle of the second century B.C. In a passage preserved by Josephus (Ap . I.205-11) he reports that Ptolemy entered Jerusalem on the seventh

[63] See Volkmann, RE s.v. "Ptolemaios (1)," 1631-35; and also the bibliography and survey in Murray (1972) 141-42; and Seibert (1983) 224-25.

[64] On this question, see J. Hornblower (1981) 55, 63. Cf. Sacks (1990) 78-79 et passim .

[65] On philanthropia as a Hellenistic ideal, see Rostovtzeff (1940) III.1358 nn. 4-5; Bell (1948) 33-37; Sinclair (1951) 291; Meisner (1970) 145-78; Aalders (1975) 22-23, 90; Préaux (1978) I.207. For sources, see, e.g., Isocr. Nic . 15; Polyb. V.11.6; Pseudo-Aristeas 265. Cf. further pp. 152-53 below, and Meisner (1970) 162-78 on its appearance in Jewish Hellenistic literature.

[66] It was not that easy to do: see Dion. Halic. De Comp. Verb . IV.30.

day, on which the Jews refrained from any work, taking advantage of the failure of the inhabitants to take up arms and defend the city on this day (209-10). Agatharcides concludes by stating: "The ancestral land [of the Jews] was delivered into the hands of a harsh master [

A brief look at these sources shows that they are mutually independent.[68] The information is transmitted from the viewpoint of the various parties involved: a Palestinian Jew, a gentile from the Ptolemaic

[67] Cf. also the abbreviated version of Josephus' in Ant . XII.6. On the superiority of the version in Against Apion , see M. Stern (1974-84) I.109; Bar-Kochva (1989) 479 and nn. 11, 14. For an interpretation of the sources and the question of defensive war on the Sabbath, see Bar-Kochva (1989) 477-81.

[68] Contrary to A. L. Abel (1968) 254 n. 2, 257, who argues that Pseudo-Aristeas's story about the deportation and enslavement originates in Agatharcides. Josephus's quotation, which recounts only Ptolemy's entry into Jerusalem, contains Agatharcides' version in its entirety. Had there been any additional information in Agatharcides, Josephus would certainly have quoted it as well, since he was so interested in proving that the Jewish nation was mature and involved in world events at the beginning of the Hellenistic period. Agatharcides did not refer to this event anywhere else: the episode about the conquest of Jerusalem does not appear in the correct historical sequence but incidentally in the context of third-century Seleucid history. He reports the unfortunate end of Stratonice, the Seleucid princess, caused by her superstitious beliefs, and compares it to the Jewish adherence to the rules of the seventh day, which facilitated the occupation of Jerusalem by Ptolemy I. It stands to reason that had the events also been recorded in the context of the Successors period, the account would have been much more detailed, and Josephus would then have preferred to quote that rather than the short version. See also M. Stern (1974-84) I.104 and n. 3 against the conjecture that Agatharcides was used as an authority on Jewish matters by later writers.

court, and a Jewish Hellenistic author from Egypt. Each recorded the piece of information that concerned him most. Their later date (with the possible exception of the Palestinian Jewish source) does not detract from their general reliability. Although they represent opposing interests and positions, they agree in regard to the essence of the events: Ptolemy I treated the Jews unfairly and cruelly. The story gains special credibility from its recording by Agatharcides: being close to the Ptolemaic court, Agatharcides had access to royal sources. The expression "harsh master" (

The sources do not date precisely the confrontation between Ptolemy and the Jews. Three invasions of Coile Syria are known, in 320, 312-311, and 302/1. It has been established that the year 320 must be discounted: in that year Ptolemy personally led the naval expedition, while the land invasion was entrusted to his supreme commander, Nicanor (Diod. XVIII.43; Ap. Syr . 52 [264]).However, the various accounts indicate the personal involvement of Ptolemy in the events in Jerusalem (esp. Jos. Ant . XII.4, Ap . I.210).[70] The choice between the invasions of 312-311 and 302/1 is more difficult. In view of the historical circumstances and indications in the sources, the events could have taken place in either invasion. Those who prefer that of 302/1 point out that Jerusalem is not mentioned in the list of cities destroyed by Ptolemy in 312-311 (Diod.

[70] See Willrich (1895) 23; Hadas (1951) 98; Tcherikover (1961) 56-57; as opposed to Droysen (1877-78) II.103; Reinach (1895) 43 n. 1; Lewy (2932) 121 n. 1; Klausner (1950) II.111.

XIX.93.7).[71] The occupation of 302/1 is, on the other hand, only briefly reported (XX.113), which may account for the absence of a reference to the confrontation with the Jews. This argument is not decisive: the destruction of the cities named by Diodorus in 311 was carried out on the eve of Ptolemy's withdrawal from Coile Syria. The events that followed the battle of Gaza, half a year earlier, are, however, recorded only in general terms (an occupation of cities in Phoenicia, XIX.85.5). One may therefore suggest that the capture of Jerusalem took place in the earlier stage of the occupation of 312-311.

Nevertheless, I tend to date the confrontation with the Jews to the year 302/1. What really counts here is the evident absence of any reference to the Jews in the work of Hieronymus of Cardia. Had the event taken place at the time of the battle of Gaza, Hieronymus, who was then nearby at the headquarters of Demetrius, would certainly have mentioned it in one way or another. The drastic measures taken against the Jews by Ptolemy I were no less severe than those taken by him against other natives of the region, actions that were recorded by Hieronymus. The only acceptable explanation for Hieronymus's failure to mention the Jews in the course of his narrative for the years 312 and 311 is that no exceptional events occurred in Jerusalem. However, his silence on such an event in 302/1 is understandable. In that year he was staying with Demetrius in the Aegean and did not return to Coile Syria after its reconquest by Ptolemy I. The account by Diodorus of the occupation of the region in 302 is indeed exceptionally short, probably because he could not find more detailed information in Hieronymus's work,[72] and his text for the year 301 has not been preserved. If the Ptolemaic-Jewish crisis did occur in the days of Ipsus, this would seem to place it rather in the year 302/1, before the decision on the battlefield. After the death of Antigonus at Ipsus and the collapse of his army in 301 there was no point in Jewish opposition to Ptolemy.[73]

[71] See Tcherikover (1961) 57; Hengel (1976) 33. For the dating of the event in 312, see Willrich (1895) 23, 26; Meyer (1921) 24; E M. Abel (1951) 31; Marcus (1943) 5 n. a; Hadas (1951) 98-99.

[72] As opposed to A. L. Abel (1968), who draws the conclusion that there was no deportation and enslavement in the time of Ptolemy I. See also M. Stern (1974-84) I.108.

[73] I would refrain from seeking support in Agatharcides' statement that the Jews came under "a harsh master" (Ap . I.210). This statement does not necessarily indicate a continuous long period of rule and could also have been applied to a period of a few months, even by an author like Agatharcides, who was celebrated for his accuracy of expression (for details, see Phot. Bibl . 213 = FGrH IIA p. 260, no. 86 T 2.6). Similarly the use of the attribute Soter in Josephus (Ant . XII.3) cannot be used to determine the time of the event. On its first application in 305, see Paus. I.8.6, and cf. Diod. XX.100.3, Athen. XV.616; and see Kornemann (1901) 72; Moser (1914) 72.

Does the last conclusion lend credibility to the information about the cordial relationship between the Jews and Ptolemy in the days of Gaza? Taking a number of considerations into account, the answer is in the negative.[74] The account of the attitude of the occupied populations outside Egypt in 312-311 indicates a generally hard-line policy. Had the Jews been favored vis-à-vis other nations, this would have given them a strong motivation to support Ptolemy in 302/1. I do not see how relations between the two sides could have deteriorated to such an extent in the decade before Ipsus, after the great "philanthropy" attributed to Ptolemy in 312, and the alleged enthusiastic response of the Jews, many of whom are even said to have followed Ptolemy to Egypt in order to assist him in state affairs. It should also be kept in mind that Judea was reoccupied by Antigonus half a year after the battle of Gaza, and consequently in the eleven years preceding the violent events of 302/1 Judea was not under Ptolemaic rule, so that there was no opportunity for a buildup of tension. Ptolemy's hostile measures at the time of Ipsus must have been a natural continuation and result of the relationship between ruler and subjects in the previous periods of Ptolemy's reign in Judea.

No less significant than the evidence for harsh treatment of the Jews by Ptolemy I is the absence of any reference to good relations between Ptolemy I and the Jews in Pseudo-Aristeas. It has already been mentioned that the author admired the Ptolemaic dynasty and strove to demonstrate its favorable attitude toward the Jews. He even tried to excuse Ptolemy's role in their deportation and enslavement. Such an author would not have missed an opportunity to prove his case and put the personality of Ptolemy in a better light if he had been acquainted with the Hezekiah story. The story would even have offered him a most attractive demonstration of Jewish good will toward the dynasty and a flattering explanation for the development of the Jewish community in Egypt: a voluntary immigration headed by the High Priest, aimed

[74] As opposed to Lewy (1932) 121 n. 1; Guttmann (1958-63) I.67; Tcheri-kover (1961) 56; M. Stern (1974-84) 1.40.

at making a contribution to the building of the Ptolemaic kingdom. Would this author, who fabricated the involvement of the Jerusalem High Priest and Ptolemy II in the translation of the Pentateuch into Greek, an entirely internal matter of the Alexandrian community, have passed over such a story? The conclusion from these observations must be that the collective memory and written records of Alexandrian Jewry in the generation of the Letter of Aristeas (whatever its exact date may be) did not contain any tradition of friendly relations between Ptolemy I and the Jews, nor of a voluntary immigration in his day.

Another difficulty inherent in the story brings us one step further toward correctly understanding it: Would Hezekiah, who is described as the Jerusalem High Priest, have emigrated to Egypt of his own free will and brought with him many other Jews besides? All this at the age of sixty-six (Jos. Ap . I.187), despite the explicit biblical prohibition and warnings not to emigrate to Egypt,[75] and when Judea had come under the control of a ruler said by the author to have demonstrated his good will to the inhabitants? Any migration from the Holy Land to Egypt was usually brought about by some compelling circumstances such as severe drought, deportation, or invasion by a northern enemy.

When this last consideration is combined with the other data that prove Ptolemy I's hard line toward the populations outside Egypt and his maltreatment of the Jews, the only way any historical value may be conceded to the Hezekiah story is to suggest that in reality the move was a forced deportation and not a voluntary emigration. And if this was indeed the case, it should rather be dated to the days of Ipsus. The author, then, transformed an exile into an emigration. Why did he do this? The question will be answered later on, after we have become acquainted with other aspects of his book. But why did he change even the background of the event and date it to the days of Gaza? Presumably he was well aware that because the traumatic experiences of the exile and enslavement in 302/1 B.C. were deeply rooted in the memory of the Jewish community in Egypt, dating his false version of the events to the days of Ipsus would discredit him at the outset.

We thus see that the information attributed to Hecataeus about the relationship between Ptolemy and the Jews in 312-311 B.C. and the voluntary migration of Hezekiah and his people does not stand up to

[75] See in detail pp. 234-36 below.

historical criticism: it contradicts information from other sources, as well as historical circumstances and Jewish tradition, and was unknown in Jewish Hellenistic circles in the time of Pseudo-Aristeas. This conclusion does not permit us to believe that the Hezekiah story was recorded by Hecataeus of Abdera.

As Hecataeus was close to the court, it might naturally be suggested that he sought to color events in a positive way. But the drastic measures taken by Ptolemy I against the Jews indicate a particularly virulent animosity between the two sides in his time. Why and for whom, then, should Hecataeus have wished to fabricate such a fanciful story about kind treatment of the Jews by Ptolemy and their enthusiastic response? This was not the practice of Ptolemaic courtiers and court historians in such cases, certainly not of authors of his standing. Even the court chroniclers, who lauded the occupation of Coile Syria in 312-311 and 217 in panegyrical terms, did not fail to emphasize the strong opposition the Ptolemaic rulers had to face from the local population after their victory over their Hellenistic rivals, and the severe retaliatory measures taken by them.[76]

Be that as it may, the absence of any reference to the Hezekiah story in Pseudo-Aristeas comes up here again and decides the issue: the author of Pseudo-Aristeas was well versed in Alexandrian literature and familiar with Hecataeus's works.[77] He even quotes a reference to the Jewish Holy Scriptures from one of them (para. 31),[78] which indicates that he indeed took great interest in Hecataeus's attitude toward the Jews. A monograph on the Jews by Hecataeus, especially one so enthusiastic, would surely have been known to him, and the Hezekiah story Would not have escaped his notice.

To close the discussion, a recently suggested interpretation of the Hezekiah story deserves attention. According to this, in the days of Gaza the Jewish community in Judea was divided on the issue of political orientation, and Hezekiah the High Priest supported Ptolemy. When

[76] On the "satrap stele" of 312/11 see nn. 63, 64 above. On the Pithom stele, which records the events of the battle of Raphia, see Gauthier and Sottas (1925) 30 line 23; Thissen (1966) 19, 60-63.

[77] See E. Schwartz (1885) 258ff.; Wendland (1900a) 2; Hadas (1951) 43-45; Murray (1970). 168-69 and there the parallels to Hecataean Egyptian ethnography.

[78] The quotation could not have been taken from the book On the Jews . See below, pp. 140-42, esp. p. 141.

the latter withdrew, Hezekiah, fearful of Antigonus's punishment, chose to leave the country with his followers.[79] This reconstruction still assumes a deliberate "inaccuracy" on the part of Hecataeus in describing Ptolemy's general attitude toward the occupied population and the position of the Jewish community as a whole—which, in view of what has been said above on Hecataeus, is a rather remote possibility. It also implies a chronological mistake in the story: the Jewish High Priest and many Jews are said to have migrated to Egypt when "Ptolemy became master of Syria" (Ap . I.186), and not at the time of the withdrawal to Egypt. Such a mistake can hardly be attributed to a contemporary author so close to the court. Furthermore, this theory does not provide an explanation for the absence of any mention of the story in Pseudo-Aristeas. In addition, the numismatic material indicates that Hezekiah remained in office in Judea after the Ptolemaic withdrawal, and still held his position close to the time of the Ptolemaic reoccupation on the eve of the battle of Ipsus.[80]

Besides, there is no reference in the sources to a political division in the Jewish community in the period of the Diadochs. The later divisions known from the Ptolemaic and Seleucid periods are no evidence: they developed during generations of daily contact with the Ptolemaic regime and were the result of conflicting personal, economic, cultural, and political interests. But even in those periods, except for the days of the religious persecutions by Antiochus IV, High Priests did not leave the country when the balance of power tilted the other way.[81] Moreover,

[79] Hengel (1976) 32; Schäfer (1977) 570; Hengel (1989) 50, 190; Hegermann (1989) 131-32. Cf. Tcherikover (1961) 57; Sterling (1992) 89. The variation by Winnicki (1991). 157 ignores the explicit references to Hezekiah in paras, 187-89.

[80] See p. 256ff. below. The identification of Hezekiah as governor and not as High Priest (pp. 89-90 below) does not affect the main arguments given above.

[81] The reference in Hieronymus (In Dan . XI.14) to an emigration of the "optimates " to Egypt after the battle of Panium (200 B.C. ), mentioned by some scholars, offers no good parallel. The internal and external circumstances of the Fifth Syrian War were entirely different, and the High Priest was not among the emigrants. The information itself is rather dubious, and was not taken from Porphyry (as M. Stern [1974-84] II.462 and others suggest), at least not in its present form. The "optimates ' are said to have been taken to Egypt by the returning Scopas, the Ptolemaic general, while another piece of information, which certainly originates in Porphyry, reports that Scopas was trapped in the siege of Sidon and was forced to surrender (Hieron. In Dan . XI.15). Gera (1987) suggests that the reference is erroneous, and actually reflects a deportation of pro-Seleucid Jews to Egypt before the battle of Panium.

the policy of Antigonus toward the local populations in his realm was not of a sort that would have driven an opportunistic High Priest to flee for his life.[82] This policy was well known in Judea in 312 B.C. after three years under Antigonus. The appearance of the name Antigonus in Jewish Orthodox circles already in the third century B.C. (Avot 1.3) indicates at least that Antigonus Monophthalmus did not leave hostile memories in Judea. The strong Jewish opposition to Ptolemy in 302/1 reinforces the impression that Antigonus's policy toward the occupied population, here as elsewhere in his realm, was favorable.

3. Hezekiah the High Priest

Hezekiah, the leader of the alleged Jewish migration to Egypt, is described as High Priest (Ap . I.187-89). As was pointed out already in the eighteenth century, no High Priest named Hezekiah is known from other sources,[83] He is not mentioned in Josephus's historical account of the period surrounding the battle of Gaza, nor in his narrative of the Persian and Hellenistic periods as a whole.

Josephus records the names Johanan, Iaddous (Jaddua), and Onias as the High Priests in the late Persian age and in the days of Alexander and the Successors (Ant . XI.297, 302-3, 347). Quite a number of scholars have tried to disqualify the first two names, claiming that they are just duplicates of the names of two High Priests who served two generations earlier, at the end of the fourth century (Neh. 12.22).[84] However, E M. Cross, in a celebrated article, has shown the paponymic principle current among the ruling families in Judea and Samaria in the Persian period.[85] The authenticity of the name Johanan in Josephus

[82] On Antigonus's liberal and conciliatory policy toward the native Asian peoples, see Billows (1990) 305-11.

[83] See, e.g., Zornius (1730) 15; Eichorn (1793) 439-41; J. G. Müller (1877) 172; Willrich (1895) 31-32, 107; Reinach (1930) 36; Jacoby (1943) 62.

[84] The arguments were summarized by Grabbe (1987) 231-46, together with earlier bibliography.

[85] Cross (1975); cf. id . (1983) 89-91. The paponymic principle can also be observed in the Zadok family during the Hellenistic period (but see Ackroyd [1984] 159 n. 1).

has recently been decisively established by the coin of Johanan the Priest, which, on clear numismatic grounds, must be dated close to the Macedonian occupation.[86] This also lends credence to the name of Iaddous, described as Johanan's successor, who held office in the time of Alexander's conquest.[87]

The possibility that the name Hezekiah escaped Josephus's notice or was accidentally omitted from the sources at his disposal is highly unlikely. Josephus is proud of his precise rendering of the line of descent (diadoche ) of the High Priests, and regards it as one of his greatest achievements (Ant . XX.261). He testifies to the existence of the pedigrees of the priestly families in the public archives and to their use in practical matters like marriage (Ap . I.31-36), and says that he himself used such a pedigree (Vit . 6). According to rabbinic sources the pedigree lists of all the priests were kept in a chamber behind the Holy of Holies, and in cases of doubt final decision was passed by the High Court in the Temple.[88]

Furthermore, in Book XX of his Jewish Antiquities , Josephus gives the number of High Priests in the various stages of Jewish history up to the destruction of the Second Temple (Ant . XX.227ff.). It has been proved that these numbers were based on an authoritative list of the High Priests and not on information scattered in the books of the Antiquities .[89] The number quoted for the High Priests from the time of the Restoration until Antiochus Epiphanes (fifteen in all, XX.234)

[86] See pp. 263ff. below.

[87] The discussion about the paponymic system (and the names Johanan and Jaddua in particular) should be separated from the controversy over the reliability of the stories in Ant . XI.302-47. The verification of the two names still does not prove the historicity of the stories. See also D.R. Schwartz (1990). The results of the recent excavations at Mt. Gerizim, which showed that the Samaritan city was built around the year 200 (see Magen [1990] 83, 96; id . [1992] 38-40), strengthen the position of the many scholars who rejected them as tendentious legends. This appears also from the remains of the Samaritan temple itself, discovered in 1994 (findings still unpublished).

[88] See Middot 5.4; Sifri, Numbers 116; Tosefta, Hagiga 2.9; and Lieberman (1962) 172.

[89] Bloch (1879) 147-50; von Destinon (1882) 29-36; Momigliano (1934) 886; Hö1scher (1940) 73-75; as opposed to Willrich (1895) 107-15. See more recently D.R. Schwartz (1982) 252-54, with special reference to the section listing the High Priests from the Restoration to Antiochus V.

is identical to that which appears from the chronistic and narrative material in Books XI and XII of the Antiquities , thus rendering the inclusion of Hezekiah impossible.[90] Significantly enough, Josephus himself, who not only cited the Hezekiah story in Against Apion , but also inserted a sentence based on it in his account of the Ptolemaic era in the Antiquities (XII.9),[91] refrained from integrating Hezekiah in the sequence of his account of the historical events and of the chronistic information on the High Priests. Josephus did not usually apply sophisticated critical methods to his sources, and if he chose to ignore the name of Hezekiah in this case, it must have been only because he was convinced of the authoritativeness of the commonly accepted tradition and of the list of the High Priests of the House of Zadok available to him.

A number of scholars have suggested that the High Priest Hezekiah was merely the leading member of a priestly family or an influential priest, as the title is known to have been applied in the later generations of the Second Temple.[92] Other scholars have tried to reinforce this view by arguing that the term appears without the article, which may imply that Hezekiah was only one of the important priests who were active at that time.[93] However, in the Persian and Hellenistic periods, "High Priest" designated only the head of the priestly hierarchy, and there is not a single case in which it was applied to other priests. The loosening of the strict meaning of the term in the Roman period resulted from changes in the appointment procedures and status of the chief priest. The right of just one family to the office was rescinded. High Priests were appointed by Herod, Agrippa I, Agrippa II, and

[90] In Book XI of Antiquities : Joshua, Joiakim, Eliashib, Jehoyada, Johanan, Jaddua, Onias. In Book XII: Simeon, Eleazar, Menasseh, Onias, Simeon, Onias, Jason, Menelaus. D.R. Schwartz (1982) 254 has cogently argued that the aforementioned list was the basis for Josephus's chronistic information in Books XI and XII of the Antiquities . The absence of the names Jaddua and Johanan (the First), the late fourth-century High Priests mentioned in Nehemiah (12.22), from Josephus's account has already been explained by Cross (1975) as caused by haplography in the copy of the list used by Josephus. Unlike these two, there is no textual reason for the omission of the name Hezekiah from that list.

[91] See in detail p. 226 below.

[92] Schlatter (1893) 340; Büchler (1899) 33; Grintz (1969) 46 n. 23; M. Stern (1974-84) I.40; Schäfer (1977) 570; Rappaport (1981) 15-16; Doran (1985) 915.

[93] See Thackeray (1926) 238 n. a; Reinach (1930) 36 n. 1; Gauger (1982) 45-46; cf. Holladay (1983) 326 n. 12.

the Roman governors, and deposed in their lifetimes, the office even being occasionally sold for money. Consequently, deposed High Priests continued to bear their former title, and it was even applied to heads of rich, influential families, whose practical power was frequently equal, if not superior, to that of the officiating High Priest.[94] As for the absence of the article, this also occurs in Pseudo-Aristeas (35, 41) and the Mishna,[95] when referring to the Hasmonean High Priest. The matter is clinched by Hecataeus's Jewish excursus, which describes in detail the qualities and authority of the Jewish High Priest, stating that he was chosen by the people, and designating him without the article (Diod. XL.3.5-6).[96] If Hecataeus had been the author of the Hezekiah story, he would certainly have to be interpreted as saying that Hezekiah was the presiding Jewish High Priest. The flexible use of the title "High Priest" in the Roman period can explain why Josephus, who was acquainted with the lists of the officiating High Priests, did not delete the title attached to Hezekiah.

A new dimension to the question of Hezekiah was introduced by the discovery of the Hezekiah coins. The appearance of Hezekiah's name on those coins encouraged the supporters of the authenticity of the Hezekiah story and brought about a new wave of scholarly contributions in that direction, claiming that the information in Josephus's Antiquities was mistaken or incomplete, and that the coins proved that there was indeed a High Priest named Hezekiah at the beginning of the Hellenistic period.[97]

This deduction, however, is unjustified. To show why, the chronological framework of the Hezekiah coins must first be clarified. These coins are divided into two groups, each including a number of variations. The

[94] See the survey of the material in Klausner (1950) IV.300-301; Schürer et al. (1973-86) II.227-36, esp. 232-36.

[95] Ma'aser Sheni 5.15; Sota 9.10; Yadayim 4.1; cf. Shqalim 6.1.

[96] Noted by Tcherikover (1961) 425 n. 46. The explanations of Gauger (1982) 45-46 do violence to the essence of the sentence in Diodorus.

[97] See e.g., Sellers (1933) 73; Albright (1934) 20-22; Sukenik (1934) 178-82 (1935) 341-43; Olmstead (1936) 244; Vincent (1949) 281-94; Schalit (1949) 263 n. 22; Avigad (1957) 149; Albright (1957) 29; Tcherikover (1961) 425-26; Aharoni (1962) 56-60; Kanael (1963) 40-41; Gager (1969) 138-39; Kindler (1974) 76; M. Stern (1974-84) I.40; Wacholder (1974) 268; Holladay (1983) 325 n. 11; Meshorer (1982) 33; Goodman in Schürer et al. (1973-86) III.673; Hegermann (1989) 131.

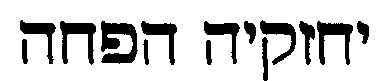

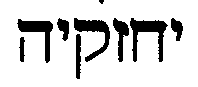

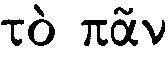

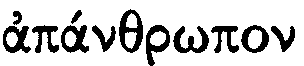

legend on the first group reads