PART ONE

THE PUEBLOS, THEIR HISTORY AND PRESENT LIFE

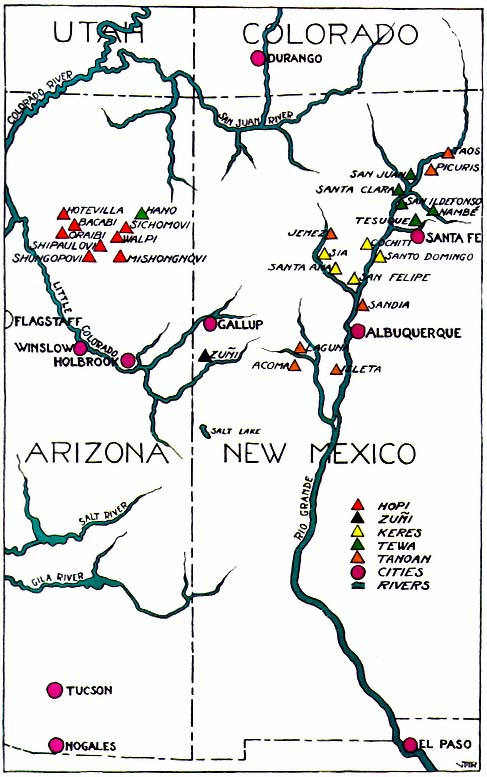

The Twenty-six Pueblos, or urban homes, of the most interesting of all North American Indian communities lie in the region described by an drag arc curving southward from Black Mesa, in the arid plateau lands of the upper Colorado River basin of northwestern Arizona, to the flat banks of the clear waters of the Rio Grande, which flows from the mountains on the New Mexico-Colorado border. Here, on a shelf of land lying between the mountains to the north and the rough country which drops away to the south, on mesa and mound, by rain-lake and stream, are built in storeyed heights around central plazas the adobe brick and stone houses of these supposedly primitive people.

History

After careful research, the archaeologist has been able to reconstruct much of the past life of these Pueblo peoples. Culture periods, known as Basketmaker I, II, and III, the dates of which are undetermined, give us definite facts about a race of longheaded (dolichocephalic) men and women who populated the mesas and canyons of the Southwest. In Basketmaker I these people subsisted on game, seeds, and berries. They led a nomadic life and were sheltered by caves in the edges of the mesas. They used clubs and stone knives, and they made coiled baskets and twined and woven bags and sandals. In Basketmaker II they began to cultivate a kind of corn and a kind of squash, and to provide safe storage spaces they dug

pits in the floors of their caves. In Basketmaker III a sort of pit house was built, a shallow excavation covered with brush. Beans and several species of corn were grown and clay pottery was made. The bow and arrow appeared for the first time and feather robes replaced the previously worn robes of fur.[1]

About the time of Christ a new race of people appeared in the North American Southwest and drove the Basketmakers from their strongholds. The bones of these direct ancestors of the Pueblo Indians are recognized by their round (brachycephalic) heads and artificially flattened skulls.

Pueblo I (ca . A.D. 1-ca . A.D. 500) saw the building of permanent houses of several rooms on the surface of the ground. The turkey was domesticated and its feathers were used in clothing. Wild cotton was cultivated, spun, and woven into cloth—an industry destined to change the material culture of the area. Pueblo II (ca . 500-ca . 900) is believed to have known the organization of a definite clan system. Each group had its own house, which consisted of a number of one-storey rooms built around a court. In this period the kiva, or subterranean ceremonial chamber, became the central element in community life. Pueblo III (ca . 900-ca . 1300) has been called the Great Period or Golden Age of the prehistoric Pueblos. The remains of large community buildings still stand as mute testimony to the group life that existed within their walls. It was the early part of this period which beheld the highest development of the cliff dwellings and the many-roomed walled towns which were built on the mesa tops and in the valleys. There was also a high development in the arts and the material crafts. Pueblo IV (ca . 1300-ca . 1700) saw the breaking up of the large centers and a migration to sites with which the present-day pueblos correspond very closely. It was in this period that the historical records of Pueblo life were begun.

In 1540 Francisco Vásquez de Coronado led an expedition of discovery and conquest into this new country from which had come rumors of

[1] 1. For numbered notes (references only) see pages 239–244, below.

the "Seven Cities of Cíbola," fabulously rich in gold and precious stones. Instead of the great riches they expected, the Spaniards found self-sustaining communities of natives. They called these communal groups pueblos , the Spanish word for villages. Exploration and subjugation were extended from the Colorado River as far as eastern Kansas. The locations of seventy pueblos were reported; many are occupied today.

The invasion followed soon after a great drought and the two calamities hastened the disintegration of the native civilization and forced the villages to consolidate. Forty years later, in 1581, history records that a party set out under the leadership of Fray Agustín Rodríguez to convert the heathen and explore the country. At the end of two years no word had been received from these soldier-priests: they had met an untimely death at the hands of their intended converts. A small expedition under Antonio de Espejo started north to trace its predecessor. Luxán, one of the party, wrote of their arrival among the Hopi: "Hardly had we pitched camp when about one thousand Indians came, laden with maize, ears of green corn, pinole [corn meal], tamales, and firewood, and they offered it all, together with six hundred widths of blankets, small and large, white and painted, so that it was a pleasant sight to behold."[2]

In 1598 Juan de Oñate attempted to colonize the country, and several communities of Mexican and Spanish settlers sprang up along the Rio Grande. By 1630 most of the pueblos had priests and churches. A period of suppression and of contention between civil and ecclesiastical authorities followed, and at the same time a resentment began to grow against the foreigners. The resentment flared into revolt in the Pueblo Rebellion of 1680. The result was the driving out of all Spaniards and the supremacy of native power for a period of twelve years. However, since no Pueblo Indian had the imagination to mold all the community groups into a strong nation, the rebel natives were at the mercy of the forceful and determined Don Diego de Vargas, who started north in 1692 and within a few months accomplished Spanish reoccupation.

Pueblo V (ca . 1700 to the present) finds the Indian permanently under the domination of a stronger power. Spanish rule ended in 1821, at the same time that Mexico threw off the yoke of Spain. There followed a period of trade. Santa Fe was at the western end of the covered-wagon trail and here the native Indian came into contact with commerce and the outside world. When the war between Mexico and the United States ended in 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo gave New Mexico to the latter country. As a territory belonging to a stable government, New Mexico gained peace. But what of the Indian? His free and open country has been replaced by small grants of impoverished land. The 'superior' and meddlesome white man has endeavored to arrange his life, judge his morals, and instruct him in a new civilization. Outwardly the Pueblo Indian has accepted the American's blue shirt and overalls, his canned peaches and coffee, but inwardly he remains aboriginal. The heritage of his race descends through him unmarred by the surface irritations of this 'higher' civilization. On his picturesque sites overlooking magnificent vistas of Arizona desert and New Mexican plain, he still lives a community life of peace and serenity that is his own. Or at least this has been so for a longer time than one might have hoped.

Location of Pueblos

Hopi.

—In the extreme western end of the Pueblo country, in northern Arizona, the Hopi villages are perched on spurs and promontories with precipitous walls and limited level spaces, seven thousand feet above sea level. Situated much as they were when first seen by the Spaniards, they are divided geographically into three groups. To the east on First Mesa are the towns of Walpi and Sichomovi and the Tewa town of Hano; on the middle or Second Mesa are Mishongnovi, Shipaulovi, and Shungopovi; and to the west on Third Mesa are Oraibi and its two offsprings, Hotevilla and Bacabi. Although a growth of piñon and juniper on the

Plate 1.

Zuñi woman in traditional dress.

mesa indicates rainfall sufficient for crops, the declivity of the land makes drainage so rapid that the rains are of little value. Nevertheless, there are springs and natural underground reservoirs which, with seepage and slow drainage, make agriculture possible in the valleys and washes.

Zuñi.

—To the south and east, on the desert of western New Mexico, is a strip of land roughly following the course of the Zuñi River from its headwaters near the Continental Divide to a point near the Arizona border. From rugged forested mountains slashed by canyons there opens up to the south and west a wide, flat valley some six thousand feet above sea level. Through it the Zuñi River floods or trickles. Melting snow in the mountains or a sudden summer storm may within a few minutes transform the stream into a raging torrent which, subsiding, leaves silt and mud on its otherwise sandy banks. In the bordering hillsides to the east are perpetual springs of clear water. On a rise of ground west of the river, and in the center of the broad valley, is the principal town of Zuñi. It is surrounded by sandy flats on which is an indigenous growth of sage, greasewood, yucca, and small cacti. With care, the fields can be flooded and cultivated to raise the crops which are so essential to the life of these people. On near-by mesa, cliff, and plain are the ruins of former villages, the study of which proves that the "Seven Cities of Cibola" which inspired the Coronado expedition of 1540 did actually exist—in whole or in part.[3] Today Zuñi is the sole urban unit, with the exception of four small summer settlements for the cultivation of distant fields.

Rio Grande.

—The remaining pueblos are found on the eastern slope, across the Continental Divide. They are grouped along the Rio Grande and its tributaries, all of which flow southward from the wooded and canyoned foothills of a three-sided watershed. To the west are the Jemez Mountains; to the north, the Sangre de Cristo; and to the east, the Sandia and Manzano ranges. Here, where the low-banked streams are fringed with cottonwood and willow, lie broad flats of cultivable land which provide ample agricultural areas for the needs of the adjacent villagers. With

an average elevation of fifty-five hundred to six thousand feet, these towns vary little in altitude from the pueblos farther west, but because of their accessibility, their proximity to the plains on the east, and their own diversified but closely related cultures these eastern groups present a complicated problem.

In order to understand the cultural relationships more clearly, it will be necessary to examine the linguistic affiliations.[*] These most definitely divide the villages.

The Hopi, of the west, are of Shoshonean stock and use a dialect of that branch of the Uto-Aztecan linguistic family. Zuñi has an individual language. The eastern groups, however, are of two linguistic units, the Keresan and the Tanoan. Because of their proximity to each other and the gradual infusion of outside influences it is impossible to classify with the linguistic affiliation the resultant habits and practices.

First, there are the seven Keresan-speaking pueblos:

Acoma.

—A fortified town on the top of a precipitous mesa four hundred feet above the surrounding plain, on the southernmost edge of the Pueblo span, close to Zuñi.

Laguna.

—Somewhat to the north and east, on the high north bank of the San José River, but nearer Acoma than any of the other pueblos.

San Felipe.

—On the west bank of the Rio Grande, near the mouth of the Jemez River.

Santa Ana and Sia.

—Both on the north bank of the Jemez River, respectively twelve and twenty miles from its mouth.

Santo Domingo.

—On the east bank.

Cochiti.

—On the west bank.

Both Santo Domingo and Cochiti lie farther up the Rio Grande Valley. Then there are the eight Tanoan pueblos, the sites of which, curiously enough, almost enclose the Rio Grande Keresans, as may be seen by the map on the opposite page.

* See Appendix, p. 235.

Isleta and Sandia.

—On the west and east banks, respectively, situated far to the south of the Keresan group on the Rio Grande. These pueblos form the southern division of the Tigua.

Jemez.

—On the Jemez River above Santa Ana and Sia and below the mouth of San Diego Canyon.

Nambé and Tesuque.

—To the east on two small tributaries, the Nambé and Tesuque rivers, a few miles north of Santa Fe.

San Ildefonso.

—On the east bank of the Rio Grande.

Santa Clara.

—On the west bank.

San Juan.

—Farther north on the east bank.

The five last named form a group of towns on the sand dunes and plains occupied by the Tewa division of the Tanoan stock. The Hano, of the First Mesa of the Hopi, are emigrants from these.[4]

Finally there are:

Picuris.

—At the foot of the Picuris Mountains.

Taos.

—The most northern of the pueblos, on both sides of the Taos River.

These two pueblos form the northern division of the Tigua.

Climate

In general these varied groups of people live in a high, semiarid country watered by winter snows, sudden summer showers, and rivers from the mountainous north. Here, also, the southwest trade winds drop their moisture throughout the year. However, moisture is much needed in midsummer—by late July and August. It is at this time that the greatest activity is apparent among those cults whose duty it is to produce rain. The climate, on the whole, is healthful and invigorating. The temperature is fluctuating: intense heat of the summer day is mitigated by cool nights, and the hardship caused by the few winter storms is more than alleviated by the many days of unbroken sunshine. It is thus possible to spend much time out of doors.

Social Customs

The Pueblo Indians stand out sharply from other culture groups of North America. They have an urban existence and consequently have developed sedentary habits. They live indoors, rise late, and stay up on winter nights and gossip. Their entire life is influenced by their almost complete dependence upon agriculture for their food supply. Even their architecture is predetermined by the necessity of storage rooms for the harvest. The destructive forces of nature must be controlled, they believe, by magic, and the maturing of the crops is due to a pantheon of all-powerful spirits, including the Sun, the Earth, the Wind, and the Clouds.

Their permanent homes allow room for storage of produce, clothing, and sacred ceremonial paraphernalia. Compared with other semipermanent or roving peoples, they are rich in worldly goods. However, their concern is with tribal unity and not with personal prestige. Their lives are thoroughly formalized and highly ritualized, and they are greatly influenced by what we call superstitions. "Despite centuries of white contacts, they preserve their native culture perhaps more completely than any other Indian group in North America. Particularly is this true of their religious life, about which the eastern Pueblos ... have built up an almost impenetrable wall of secrecy."[5]

Architecture

The pueblo town is like a living organism; it is always being built and always being repaired. It may be a group of houses built in a pyramidal pile enclosing courts and plazas, as at Zuñi; or it may be built in two units, one on either side of a river, as at Taos; or again, it may be built in parallel lines, as at Acoma.

These flat-roofed houses are built together and on top of each other to the height of two or more storeys. The roofs are open paths from one neighbor's door to the next. Formerly, the entrance to the ground-floor

room was a hatchway in the roof through which a ladder projected. There was no other opening, and the smoke was obliged to find its way out through this hole. The plaza, the center of all activity, was reached by descending a movable ladder which was drawn up in times of danger. The inner rooms of the houses were used for the storage of corn, other foods, and ceremonial equipment. Only members of the family might

Figure 1.

Taos.

enter these chambers. Nowadays, there are doors and windows in all the outside rooms, and hooded fireplaces with chimneys.[6]

The building material used in the western pueblos is mostly stone, held together with adobe mortar and the whole covered with adobe plaster. In the east an unmolded adobe brick is used. The floor is usually packed earth, although it is sometimes paved with slabs of stone. The roof beams are of cottonwood, pine, or spruce, with cross poles covered with brush and earth. Within recent years modern tools and modern transportation have made it possible to build larger rooms, because longer timbers to serve as roof beams can be brought from the distant places — forested mountains — where they are procurable.

The heavy work of building is done by the men, but the women do all the plastering and finishing. It is customary, at least once a year, to do all necessary replastering, both inside and out, and to mend the holes and washes made by the heavy rains.

Agriculture

Corn is the basis of Pueblo economic life. Various seed and melon plants are now grown, but corn, beans, squash or pumpkin, some varieties of gourds, the sunflower, and a kind of cotton were aboriginal. Other plants were introduced by the Spaniards and the Mexicans. Planting was done in April and May. The Hopi have a series of nine specified plantings, determined by the sunrise, between mid-April and June.[7] The Indian believed that planting must be done at a certain phase of the moon; for example, a waning moon was thought to have a bad influence upon the growth of plants.

Corn is the staff of life and the center of ceremony. Seed corn is kept two years so that in the event of a dry season there will always be enough for another planting. The corn is quick-growing and drought-resisting. It is planted deep, in irregular hills; often it depends upon seepage or underground water to quicken it into life. Colored strains of corn have been cultivated by the Pueblos for centuries, and the colors have ceremonial significance. A special blue corn is planted in May for the town chief of Cochiti.[8] A central place in myth and legend is given to the Corn Maidens, and the various colors of the grain are related to the directions. "The Tewa recognize seven varieties with the corresponding color directions of association and personifications. They are the following:

|

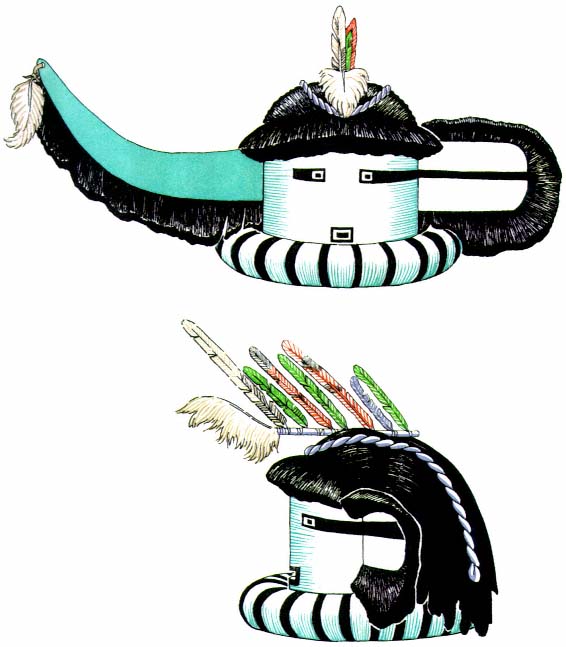

Plate 2.

Kachina doll, carved, painted, and decorated to represent a Sio Shalako

from Hopi. Such representations of the supernaturals acquaint the

children with the many powerful Beings who aid and protect them.

Fields are often owned by clans, as among the Hopi, or individually by the men and women, as in the east. The men work the fields, the women occasionally helping with the planting, and the entire family joins in the harvest. Communal labor is employed in certain fields and the crops from these are given to the town chief. This august person does not work, but spends his time in meditation on matters which are supposed to be for the good of the community.

Wild seeds and plants were formerly used for food. These included piñon nuts, acorns, juniper berries, yucca fruit, and many cacti. Certain plants and herbs still provide flavoring, and from others are obtained colors and adhesive gums used for dyeing materials and decorating masks.

In former days another major activity of the Pueblos was hunting, for the obtaining of food and skins. The hunting societies were influential; their leaders still hold active office in the round of ceremonial life.

Pottery

Clay pottery is made by hand without the use of a potter's wheel.[10] The larger vessels are for water and storage. The cooking is done in crude, undecorated pots which serve only a practical purpose, but the water jars and the bowls used for serving food or for ceremonials are delicate in form and beautiful in design. The shapes, the use of colors, and the decorative motifs differ with the various localities.

Dress

Before the Spaniards came, the men's dress consisted of soft-tanned deerskin or woven cotton. There might be a shirt, a breechclout, a kilt, and a robe of rabbitskin strips and, at an earlier period, a feather mantle. Leather moccasins or yucca-fiber sandals were used. The women wore a garment made of a rectangular piece of cloth wrapped around the body, fastened over the right shoulder, and sewed up the right side (pl. 1). Thus the left shoulder and arm remained bare and free. A long, wide belt was

wrapped several times around the waist. A square of cloth, with two corners knotted under the chin, was allowed to hang down the back. Most of the time the women wore no foot covering, although long, wrapped moccasins of soft deerskin were worn on occasion. In the cold Taos country, snowshoes were worn in winter; elsewhere the feet were protected from snow by a piece of fresh deerskin with the hair side inward.

Figure 2.

Hair dressed in side whorls worn by a maiden as a sign of virginity. An

old-style form made of cornhusks supplied the base of the butterfly shape.

Today—aside from the American store clothes—the men's dress is reminiscent of the Spanish Colonial period, modified, of course, by years of influence. The women retain their aboriginal dress, which is now worn over an undergarment.

Hair arrangement.

—The long, black hair of both men and women is often queued, doubled over itself, and bound with a band at the nape. The sides are cut even with the ear lobe, and sometimes the women's hair is banged to the eyebrows. In some dances the hair hangs to the chin, simulating a mask or the Oriental veil (pl. 10).[11] The Hopi matron's hair is parted and gathered in two locks over the ears. "Each lock is wound over the first finger and the end drawn through as the finger is withdrawn."[12] The upper end of the lock is then wound with hair cord. The unmarried Hopi girls twist their long side and back hair on great eight-inch whorls

which are worn over their ears to suggest the butterfly, the symbol of virginity. At Taos the man's hair is parted in the middle and allowed to hang on each side of his face in a braid or roll wrapped with yarn.[13]

Communal Life

There is little or no individual life within the pueblos. Work, play, and religious rites are group activities prompted by communal needs and aspirations. At designated times the crops are planted and harvested by working parties.[14] Houses, fences, and irrigation ditches are built by a man and his immediate family, and all who constitute his blood relations may be called upon to work together. Games are played by individuals and between tribal units which also participate in religious ceremonies. These ceremonies are directed in a stipulated pattern by various groups of men who have inherited or gained the positions of leadership. In the daily and yearly routine "they have hardly left space for an impromptu individual act in their closely knit religious program. If they come across such an act they label the perpetrator a witch."[15] Ruth Bunzel, speaking of Zuñi, says: "The supernatural, conceived always as a collectivity, a multiple manifestation of the divine essence, is approached by the collective forces of the people in a series of great public and esoteric rituals."[16]

The groups with which an individual may be associated are determined by birth, adoption, marriage, or election. The matrilineal exogamous clan system of the Hopi-Zuñi divides the villages into a series of named groups to one of which a child belongs from birth. This means that a child inherits its clan membership from its mother and must marry outside that clan. The clans establish the family line of descent in respect to certain official capacities in connection with other groups or cults. There are also strong clan systems in Acoma, Laguna, among the Rio Grande Keres, and even at Jemez. Farther east, among the Tewa, they become more and more feeble until finally, with the Tigua of Picuris and Taos, there are no clans at all. Strangely enough, Isleta has a pseudo clan division, following

the east. Conversely, there appears the moiety, a more or less patrilineal division of the town into two parts, with a tendency toward endogamy (marriage within the group) fully developed among the Tewa.

"This division of the pueblo into two parts, or moieties, has usually been described in connection with social organization. It is true that it looms as large in the consciousness of the western pueblos, but it has no relation to the social organization ... and ... is evidently a ceremonial device associated with the kiva and with rain and fertility functions."[17]

"In the west the women own the houses, in the northeast the men, a mixed system of ownership prevailing in the towns between. In the west there are an efflorescent mask cult and an elaborate service of prayer-sticks or prayer-feather offerings, which diminish steadily to the east and north."[18]

Government

A governor and his aides (a system instituted by the Spaniards) are elected annually in most of the villages. However, they have no real authority, but act merely as go-betweens for the priestly powers and the white man. The government is actually carried on through the ruling religious groups. In the west the Priest of the Zenith (or Sun), who inherits his office, stands at the head of the council and acts as leader. When the moiety divides the town into Summer and Winter people, there is a priest head and his council for each group, one serving throughout the first and the other throughout the second part of the yearly round.

Manners

The Pueblos are a modest people—polite, well behaved, and noted for mildness of manner. Ruth Benedict points out that "the southwest pueblos are ... Apollonian, and in the consistency with which they pursue the proper valuations of the Apollonian they contrast with very nearly the

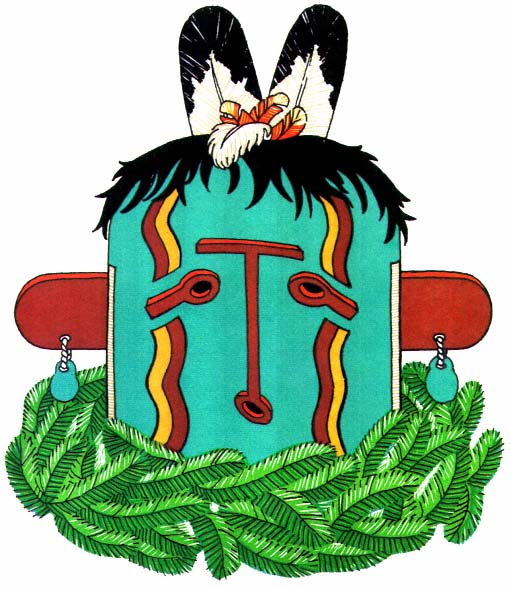

Plate 3.

Saiyataca, Zuñi longhorn kachina mask. An

excellent example of occult symmetry in design.

whole of aboriginal America; they possess in a small area islanded in the midst of predominantly Dionysian cultures an ethos distinguished by sobriety, by its distrust of excess, that minimizes to the last possible vanishing point any challenging or dangerous experiences. They have a religion of fertility without orgy. They have abjured torture. They indulge in no wholesale destruction of property at death. They have never made or bought intoxicating liquors in the fashion of other tribes about them, and they have never given themselves up to the use of drugs. They have even stripped sex of its mystic danger. They allow to the individual no disruptive role in their social order."[19]

Accompanying this sobriety and evenness there is a pronounced secretiveness which makes it almost impossible to disentangle their extraordinarily complex religious and ceremonial life. For centuries they have successfully evaded the curious and the inquiring. Even the Catholic friars who came up from Mexico to establish religious centers and to 'convert the heathen' were able to scratch only the surface of their ceremonial system, and instead of bringing salvation to the 'heathen' they found in the end that there remained only the same Indian rite clothed superficially in Catholic custom. The saints' days are celebrated, to be sure, on dates stipulated by the Church, and these celebrations may include the usual Mass and church observances, followed by general festivity; but the dance, the native prayer and worship, the fundamental aspect of Pueblo religion is as Indian today as it was before Coronado's visit in 1540.

Religion

"The religious life of the Pueblos," says Edgar L. Hewett, "is the key to their existence. Their arts, industries, social structure, government, flow in orderly sequence from their beliefs concerning nature and deific power. ... In its essence it is almost what modern science has attained to—the conception of Nature and God as one."[20]

It is readily understood why the Indian felt so dependent upon the sky,

the earth, the sun, and the natural elements. He needed all these for the cultivation of his crops, from which he provided himself with food and clothing, and these things were needed for the growth of game. Everything in his daily existence depends upon them. He considers himself at one with the things about him. The whole world seems animate: each object in space or time exists and has a personality. There is no more concern over personal religious experience than over personal prestige and profit. His own importance in the scheme of existence is no more than that of a tree or a rabbit. "The religion of the Pueblos ... rests on two basic ideas: namely, a belief in the unity of life as manifested in all things, and in a dual principle in all existence, fundamentally, male and female."[21]

Pantheon of supernaturals.

—To this unified belief in nature there is added the belief that certain attributes exist only in particular forces. From this springs a kind of pantheon of supernaturals who embody these forces. Varying little throughout, they may be classed as: cosmic—sun, moon, stars, earth, and wind; animal—beast of prey, water serpent, and spider; ancestral, or the dead in general—the kachina, the skeleton, and the war gods.[22] All these supernaturals exhibit anthropomorphic characteristics and are said in myth to have mingled among men in human form. "Even the spirits conceived of as animals have only to remove their skins and they will become men in shape and appearance, although retaining their supernatural attributes and powers."[23] These supernaturals are graded according to their power and are believed to live in the under regions of the world as well as the four quarters and the heavens above. The importance attributed to them in the different pueblos seems to vary as the sphere of influence or function which they represent is of importance to that group.

Organizations.

—These forces, or beings, may be either friendly or hostile. They require respect and veneration. Gifts and assistance are sought from them by offerings, prayers, or magical practices, carried on by a complicated group of secret societies and fraternities.

These societies are practically unlimited and there is scarcely a limit to the number to which each man may belong. At adolescence every boy is initiated into a kachina cult or kiva society, an esoteric group which approaches the supernatural through ritual and sometimes through impersonation. A youth or man may, through a vow made in sickness, be promised to one of the medicine societies found throughout the pueblos, except in Picuris and Taos, where the kiva societies perform these rites; or, if he 'takes a scalp', he is forced to join the warriors' society to 'save' himself. He may be called upon to join the priesthood or, if he is connected with a sacerdotal household, he may be asked to fill an official position, or he may be appointed or elected to it. There are also innumerable cults. "Most men of advanced age are affiliated with several of these groups."[24]

Each esoteric cult is dedicated to the worship of some special supernatural or group of supernaturals. Each has a priesthood, a pattern of ritual, permanent paraphernalia, a calendric cycle of ceremonies, and a special place for the rehearsals, rites, and performances.

Kiva.

—In each pueblo there are two or more kivas.[25] A kiva[*] is a chamber or room built especially for the meetings of a group and used by its members as a clubhouse for the men, where they come together to talk and work.[26] It is here that many of the semipublic ceremonies take place. At certain times it can be called the theater for religious entertainment.

At Hopi each village has six kivas, in accordance with the cardinal directions. These are subterranean rooms, sometimes built in the mesa side with one exposed wall in which a small hole admits light and air, the roof being kept level with the mesa top. The rooms are rectangular and measure about twenty-five feet long and some fifteen feet wide.[27] About one-third of the floor space is raised a foot above the rest. This may be reserved for spectators of the indoor performances. In the center of

* "Kiva," says Ruth Bunzel, "is a Hopi word which has become the standardized term ... for the ceremonial rooms of peculiar construction which are found in all ancient and modern pueblos."

the roof is the entrance hatchway, through which the long ladder extends. Directly below this opening is the fireplace, a pit which uses the hatchway as a smoke hole. At the lower end a plank with a tightly plugged hole covers a cavity in the floor which represents the place of emergence from the inner worlds, and through which the prayers of the people are supposed to return to the Great Ones. Along one or more side walls is an earthen ledge which serves as a seat and, at the lower end, provides a shelf upon which religious paraphernalia are placed.

The six ceremonial chambers at Zuñi are square buildings incorporated in the house units. There is a hatchway entrance from above, as well as a communicating door to an adjoining house, and a small wall opening on the street side for air. A covered fireplace is found directly below the hatchway and earth ledges are built out from the walls. However, here there is no hole to the underworld.[28]

At Acoma, also, the seven ceremonial chambers are in the house blocks. They are designated as special buildings by the double ladders which lead to their roofs. The poles of these ladders are longer than ordinary, and the crosspieces at the tops are carved with designs suggestive of lightning symbols.[29] Only one of the Acoma chambers has the planked resonance hole in the floor.

One other kiva form is significant. In the Rio Grande region separate circular buildings may be found beside the dance plaza. They are semisubterrane, and sometimes the tops are built to a considerable height. A fine example at San Ildefonso has an outside stairway leading to the top, where a ladder through a hatchway leads one down into the interior. A small opening on the side provides light and air. At one dance I saw there, the more slender and agile dancers climbed in and out through this opening. In some places these round houses appear to be used by different groups and constitute a dressing room or exhibit space for ceremonies;[30] other rooms or kivas in the various Rio Grande pueblos serve as society

Plate 4.

Hehea, Hopi mask, with collar of evergreen.

and moiety headquarters. There may be several different types of kivas in one village; for example, Isleta has two round houses, two detached rectangular houses, and a separate building for general assemblage.[31]

Ritual.

—"There are definite fixed rituals and prayers for every ceremonial occasion."[32] The general form is a retreat followed by a dance.

Figure 3.

Round kiva at San Ildefonso.

The retreat is always private, but the dance may be performed publicly in the plaza or semiprivately in the kivas or houses of the cult groups or in the home of the leader.

Along the Rio Grande the retreat lasts from one to four nights; farther west the retreat and subsequent dances may require as many as sixteen days. It is often preceded by a public announcement from the chief or town crier. For the period of retreat an arrangement of sacred objects is made at one end of the kiva. A formal altar of painted wooden slats is erected and decorated with feathers and spruce boughs. On the floor in front of the altar is a painting of special significance. It is made by a priest, and his materials are colored sands or corn meal, which he allows to run through his fingers into compositions delicate and beautiful. Bowls of medicine water and various objects with fetishistic powers are handled and set upon stipulated spots about the altar. Perfect ears of corn, which

sometimes are hollowed out and filled with a variety of native-grown seeds and decorated with beads and feathers, symbolize life tokens and represent the ceremonial chief, the clan head, or the individual society members. Crudely cut stone animal forms, wooden images, masks, and claws and skins of beasts of prey are placed in orderly groups. Altar masks are rarely worn in ceremonies. They are supposed to have come to the earth with the Pueblo people, and since they are so very old, they are regarded with great respect.[33]

Accompanying this altar setup are certain prayers and ritualistic observances. The most stylized as well as the most casual pattern is surrounded by a great background of myth and legend. These are handed down by word of mouth, and it is an important duty of men old in office and in years to instruct the younger men in all ritual forms, at the same time reminding the others of their backgrounds and origins. The form of the ritual is that of a chant which retells the myth centering in this particular rite and thus forms a background for the appearance of certain characters and the final public demonstration. Leslie White says of a religious observance at Santo Domingo: "The retreat as well as the subsequent masked dance is a little play. The medicine men go back to Shipap [the place of their emergence] to see the mother ... to get her to send [the Cloud People]. Hence the chamber into which the society retires is called Shipap. For four days the medicine men are not seen at all, for they are not in the pueblo. They are in Shipap. After the retreat is over the doctors reappear ... and a masked dance is held [they have brought the Shiwanna[*] back with them]."[34]

Those in retreat practice various forms of abstinence. Meat, grease, and salt are abstained from, and at certain times there is absolute fasting. Continence preceding and during any ceremonial action is held to be particularly important. Purification is required in all the pueblos. Bathing, especially washing of the hair, is of great significance. To insure in

* Shiwanna means Rain Makers, anthropomorphic spirits who bring rain.

ternal purification, emetics are taken each morning of the retreat and after the final dance.

The men who take part in the retreat are virtually prisoners. They spend all their time in the kiva or society chamber, where they perform rituals or prepare offerings, costumes, and the paraphernalia for the final performance.

The most common offering is the prayer stick. Its appearance and manufacture will vary with the pueblo in which it is made and the supernatural to whom it is dedicated. It is usually a small stick carefully smoothed and painted, and it has a dressing of various feathers attached with a homespun cotton cord. These are placed before ancient shrines or buried in the fields or at the river's edge. Another form of offering is corn meal or pollen. This may be sprinkled on the dancers, the altars, and the paraphernalia. Every morning those who hold sacerdotal positions make offerings of corn meal to the Sun. Corn meal is significant in every altar ceremony.

Cults.

—The Pueblo Indian early believed that he was dependent upon the Great Ones for his sustenance and well-being. Hence there grew up a cult, the Kachina Cult, for the worship of these Great Ones; and likewise cults of veneration for those beings or forces which regulated other phases of his existence. Inimical beings developed the War Cult; the desire for meat and skins created the Hunt groups; and the mysteries of bodily ills brought about the Medicine societies, the animal patrons of which were supposed to give them insight and power.

"The katcina cult is built upon worship principally through impersonation of a group of supernaturals."[35] Their cult "seems to be the most fundamental aspect of pueblo religion, although the katcina cult itself is probably a later overlay, upon an older weather control organization. The katcina spirits are supernaturals who bring rain and good health. They were created at the time of the first emergence of the people from their underground home or shortly thereafter. Some of the pueblos say

that part of the people fell in the water and were drowned after the emergence, thus becoming katcina."[36]

These supernaturals live in an underground world[37] or beneath the surface of the Sacred Lake, as at Zuñi.[38] The new-born are thought to come from one of these places, and the dead return there. Here the kachinas spend their time in singing and dancing. They possess rich clothing, valuable beads, and beautiful feathers. A very long time ago, the legends tell, the kachinas, whenever the people were lonely and sad, would come to entertain them with singing and dancing in the plazas, or perhaps in specially prepared houses of the pueblo. This would bring gaiety and joy to all the people. When the fields were parched and dry, the kachinas would come bringing the refreshing and revivifying rain. They particularly watched over the Pueblo peoples and provided for them. At Zuñi, it is said that each time the kachinas came they took one of the people back with them into the underground world; thus at Zuñi the joy at the coming of the kachinas was not unmixed with sorrow.[39] At Acoma there was a great fight because the people had mocked and criticized the kachinas.[40] As a result the kachinas decided that it would be better if they no longer visited the village in person. They therefore showed the people how to copy their masks and costumes, taught them their songs and dances, and exhorted them to perform the dances correctly, to live good lives in observation of custom and ritual, and to honor and respect the kachina. In return the supernaturals would come and be with them in spirit and would bring prosperity.

As soon as the impersonator dons the mask of the supernatural, he is believed to become that spirit. As a consequence he is supernatural and must not be approached or touched during the ceremonies, and he must be discharmed after the ceremonies before he again becomes mortal. "Instituted according to tradition, solely as a means of enjoyment, they

Plate 5.

Many-colored Zuñi Salimapiya of the Zenith, with collar of ravens

feathers,bandoleer pouch, and special feather mask ornament.

[the kachina ceremonies] have become the most potent of rain-making rites, for since the divine ones no longer appear in flesh they come in their other bodies, that is, as rain."[41]

"The katcina or masked figure has been as baffling in pueblo ceremonialism as any of its baffling features. The general concept of the katcina is simple enough. A wearer of the mask represents, in fact embodies, a beneficent supernatural bringer of rain and of abundant crops, but in the katcina conceptual complex in detail there is considerable variation as to particular supernaturals, their origin and their habitats: and as for katcina ceremonial organization or rather association of the katcina with ceremonial organizations, that differs everywhere, from tribe to tribe, even from town to town."[42]

Throughout the span of pueblos all the men belong to one or more tribal units which are associated with the Kachina Cult. In a few villages where the cult is nonexistent the ceremonial organizations center in the moiety, replete with secret rites and ritualistic paraphernalia. In the western pueblos there are six kachina groups, identified with the six directions: south, west, east, north, zenith, and nadir. Each one is lodged in its own kiva. Women, girls, and uninitiated boys are supposed not to know that the supernaturals are being impersonated by their own clansmen.

The dance.

—The climax of each ceremonial period is the prayer drama, a reverential, solemn, ecstatic final dance. It comes at the end of the rigors of retreat and abstinence and concludes the myths and legends the unfolding of which constitutes each ceremonial observance. Originated to give joy and pleasure to the supernaturals, it has been continued as an entertainment for them and as a means of instruction, diversion, and worship for every man, woman, and child in the community. An eminent ethnologist has pointed out that here is "the best round of theatrical entertainment enjoyed by any people in the world, for nearly every ceremony has its diverting side, for religion and drama are here united as in primitive times."[43]

Even the simplest dance has a variety of patterns, and the artistic costuming and stylized action keep the spectators enthralled. A performance may pantomime the story of a certain culture hero, or a legendary figure, or it may exhibit a pageant of numerous and varied characters. The mimetic Animal and Bird dances revert to a belief in an animate world where, in the long ago, man and beast lived together and understood each other. In order to pantomime the hunt, that time must be reinfused with life as when animals gave their lives willingly to aid their human brothers. At the more elaborate dances the clowns are always present. Each village has two groups of very powerful priests who masquerade as grotesque characters symbolic of their mythical origins. The clown-priest phase is universal among all the pueblos, but the grotesquetie varies.

The Mudhead is a well-known Hopi-Zuñi clown with a baglike mask (pl. 40). This mask and the body of the clown are painted earth color with clay from the Sacred Lake. The "Chiffoneti"[*] of the Rio Grande region are unmasked (pl. 39), and their bodies are painted in black and white stripes to represent the spirits of the dead. Although these clowns are the most powerful priests and intermediaries to the gods, they act the buffoon and perform impromptu interludes between the dances. They make sport of individual and group, caricaturing individual eccentricities or satirizing group foibles, and when a direct hit is scored the glee of the nonvictims breaks forth in raucous laughter. They are the censors, the mediators, and the judges for the social life of the village. Sometimes they play games or mimic the performance just ended.

These clowns are always present at kachina dances. Herbert Spinden repeats in part the dialogue with which they drew the Cloud People to a certain ceremony:

"At the appointed time all the villagers go to the underground lodge and seat themselves in readiness for the performance. Soon two clowns appear at the hatchway in the roof and come down the ladder. They

* A present-day Mexican term, commonly used.

make merry with the spectators. Then one says to the other: "My brother, from what lake shall we get our masked dancers tonight?' 'Oh, I don't know. Let's try Dawn Canyon Lake. Maybe some Cloud People are stopping there; Then one clown takes some ashes from the fireplace and blows it out in front of him. 'Look, brother; he says, 'do you see any Cloud People?' They peer across the ash cloud and one says, 'Yes, here they come now. They are walking on the cloud. Now they stop at Cottonwood Leaf Lake'. Then the other clown blows ashes and the questions are repeated. Thus the Cloud People are drawn nearer and nearer until they enter the village. The clowns become more and more excited and finally cry, 'Here they are now!' and the masked dancers stamp on the roof and throw game, fruit and cakes down the hatchway."[44]

Since the Pueblo Indians are fundamentally a peace-loving people, the so-called "war dances" were usually borrowed, sometimes actually purchased, from other tribes which were often their deadliest enemies. These dances then were known by that tribe's name, that is, Navaho, Pawnee, or Apache. The ceremony of the dance is learned in its entirety, even to the chant in a foreign language, and the dress is copied or simulated. Thus the dance can be used as counter-magic against those who originated it, although it is sometimes used merely as picturesque entertainment.

As we have noted, the dance is the event of principal importance in all these ceremonial performances. It is not a dance such as we are familiar with, but a stately movement to a solemn chant—a symbolic and pictorial rhythm which is an outgrowth of prayer just as were the medieval dramas when the Biblical stories were unfolded in action before the high altar. The result is prayer and entertainment, church and theater. Those who perform believe they are benefiting the entire community, even the outside world. Those who watch have also lent their support. During the days of retreat and ceremony the preparation of food for the performers falls upon the women members. Often one society will provide the dance which accompanies the prayers of another society performing the kiva

rites. Each person in the village gives offerings and blessings. For the final performance the people stand silently in solid blocks, looking down from the terraced housetops, or they sit motionless upon the plaza ledges. Between dances there is quiet conversation, gossip, or the subdued hailing of visitors from a far-off pueblo. These are community affairs and everyone must take part at some time during the year. The Zuñi kiva societies are required to present at least three group dances from one winter solstice to the next.[45] Thus those who do not perform are always interested and sympathetic spectators.

At the dances performed in the individual society rooms the audience is composed mainly of the women and children group members, as the men are usually participating. Seated along the sides of the room or at the raised end, they remain quietly attentive, without a change in expression, watching for hours the movement of the dance. Several groups may combine for a presentation in which each performs its own act or dance. These separate numbers are repeated simultaneously in each of the participating kivas.

The dance patterns are very simple. The most common is a long line which moves as a single unit. There may be one row of men working in perfect unison, one foot of each man raised to the same height at the same moment; or there may be two rows facing each other, with steps varied to suit the type of impersonation. Dancers depicting male characters dance more forcefully than those depicting female characters. In the Rain Dance the line of fifty or sixty dancers is squared around three sides of the plaza, but there is no circular action. The dancers themselves turn, and pause, and turn again, the sweep of movement running through the line like a breath of wind through stalks of ripening grain.

A circular pattern is followed in the women's society dances and in

Plate 6.

Zuñi blue Salimapiya of the West, whose body stain is

the fluid from cornhusks. A special kilt bas a wide border

of embroidery. Prophetic yucca leaves are carried.

those performed for curing and for war. The movement is continuous in one direction, with the participants facing the center.

A more elaborate pattern is made up of several movements. In the Rio Grande pueblos, "the public dances in the plaza are more or less processional but the advance is very slow. There are definite spots of stationary dancing and here countermarching is used to make a new quadrille-like formation."[46] Two men are followed by two women, each pair dancing as a single unit. There are no complicated figures or interweaving of dancers.

The dance steps look extremely simple. The usual one consists of a vigorous stamping with the right foot while the heel of the left foot is only slightly raised. In more lively dances both feet leave the ground alternately and give the appearance of sustaining the body in air. About these steps there is a feeling of eternity, as if, since time began, generations, nay, races of dancers had beaten with their feet the surface of the earth to obtain from it strength and power. Women often dance barefoot in order to receive fecundity from the mother of mothers. There are few arm gestures and little posturing. Each dancer has splendid body control. It is enthralling to see the vigorous movement continue without a break for fifteen or twenty minutes at regular intervals throughout the day.

Certain of the Bird dances require great strength and skill for the wheeling and circling movements which give the illusion of winged flight. The footwork is sure and delicate and the precision of each performance is remarkable. These dances as a whole are full of color and imaginative stylization based upon a hypnotic rhythm. The peculiar pulsation is almost impossible to imitate for anyone not born to the sound. The rhythm is regular, but there are skip beats and pauses which occur simultaneously in drumbeat, song, and dance.

Usually, percussion instruments provide the accompaniment for the dance. Drums vary from hollowed logs and pottery jars with skin heads to flat tom-toms. They are beaten with sticks made with a hooped end or wrapped with cotton. Rattles of gourd, turtle shell, and rawhide bags

filled with pebbles or seeds are carried by most of the dancers.[47] Notched sticks may be rasped against each other on a sounding board of wood or gourd. Occasionally, bird-bone whistles are heard—shrill notes above the steady drone of drumbeat and human voice.

All dances are also accompanied by songs or chants sung by a chorus or by the dancers themselves. Some of the songs are so old that the lan-

Figure 4.

Hopi drumstick, bent into shape when green and

bound with deerskin thong, forming a looped end.

guage is obsolete and even the singers do not know the meanings of the sounds. On the other hand, some of the old dances have new songs composed for them for each performance.[48]

The masked dances, even those in which female characters appear, are performed exclusively by men. Women take part in most of the other dances. The Corn Dance has an equal number of men and women. The Hunt Pantomimes have one or two maidens who personify the animal mothers. The women's societies perform dances in which only women and girls take part.

The dance leader always takes his position in the center of the line. The priest of the group appears at the head of the line. He does not dance, but stands chanting or praying as he displays a feather badge of office or a banner of ceremonial significance. Whenever a chorus is required, it is grouped around him.

Ceremonial Calendar

Every pueblo determines its own special calendar of ceremonies by observation of the sun. Some authorities think that the Rio Grande pueblos have adopted the white man's calendric system, thereby changing the yearly pattern. This seems to be borne out in the election of governors and the saint's day festivals, but the dances with seasonal significance are still performed in proper relation to the native calendric periods. The summer solstice and the winter solstice were the two divisions of the ceremonial year. The Indian "observed that the sun, both to the east and to the west, reached a point in the south beyond which it never traveled, and from which it commenced its return to the north. In due time the return of the sun dispelled the cold of the winter and brought warmth and life back to the earth."[49]

Thus the rituals and ceremonies closely follow the seasons. In spring, the rituals of the planting are followed by the ceremonies for germination and growth. In summer, the rites of protection of the crops coincide with the ceremonies to invoke rain. The autumn is filled with dances of thanksgiving as the gathering of the harvest evokes prayers for the fertility of the earth for the coming year. The winter season is filled with invocations. Many of these are made by the Weather Control groups, who must provide snow in the mountains to fill the rivers in spring, and at the same time man and animal must be protected from fierce blizzards and freezing winds. Many prayer ceremonies are performed by the Hunt groups, which are active at this time. The prayers and dances are a form of appeal to the animals. Formerly this appeal was that they allow themselves to be killed for the benefit of mankind; now, since there is government restriction on hunting, the appeal is that the animals intercede with the 'higher powers' to provide for man.

Thus there is an ever-recurring cycle of events to assure the continuation of life by providing food, clothing, and health.[50]

The Influence of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church has had an important influence on the lives of the Pueblo Indians, because of the missions which were established along the Rio Grande. Early in the seventeenth century, Franciscan missionaries were sent to all the villages in an attempt to convert the inhabitants to the Christian faith. A very few accepted it to the exclusion of their own beliefs. With the characteristic openmindedness of their race they have assumed the outward manifestation of a belief in God, but only as He is related to their pantheon of deific powers. An attempt was made to prohibit their native ceremonies as inimical to Christian beliefs. The Church objected to the worship of their supernaturals, and as a result kachina rituals were performed in secret, excluding all who were not initiated into the Indians' beliefs and customs.[51] Even today, when these rites are being celebrated, all unbelievers are requested to leave the village, and the streets are patrolled to guard against the intrusion of any outsiders.

The practice of exclusion has made it well-nigh impossible for any knowledge of the secret ceremonies to be obtained. Among the Hopi, where Spanish occupation was brief, there is no exclusion from rites which are public to the natives. Certain kiva ceremonies, however, are always secret and are known only to the initiated. At Zuñi, where Spanish occupation ended less than a century ago, Americans are admitted to all ceremonies, but Mexicans are excluded. It is from Hopi and Zuñi that the most information can be obtained concerning the sacred supernaturals who are featured in their masked dances.[52]

When the priests of the Rio Grande missions saw that their attempts to check the native ceremonialism were vain, they encouraged certain acts of ritual, other than those pertaining to the kachinas, as an added feature of their church days. Thus today we find many of the dances appearing hand in hand with the Catholic service. To each village a pa-

tron saint was allotted. On the church day set aside for the veneration of this saint there has been instituted a particular celebration combining both the Catholic and the native ceremonies; for instance, the celebration of St. Stephen's Day at Acoma.

Early on the morning of September 2, St. Stephen's Day, the visiting priest may be seen climbing the rugged mesa trail. He performs Mass in the old adobe mission, built in 1699 by the hard labor of the natives subjugated under the tyrannical power of the resident priest. The devout come to the church and pray. Marriages are performed and babies are baptized. Then, with lighted candles, the statue of their saint carried bravely beneath a garish canopy, they march in solemn procession around the terraced house blocks of their pueblo to the beat of an Indian drum and the wail of a pagan chant. At length, when the sacred image is couched in a temporary bower of tall cornstalks and evergreens, the typical Indian dance is performed in its honor. Turning before the holy figure, they beat and pound the earth with their feet, singing to other gods their songs of prayer and thanksgiving.

Several religious playlets have been devised from sixteenth-century ecclesiastical drama, but these are costumed in accordance with modern Indian ingenuity and provide nothing of interest in the way of native ceremonial dress.

Indian life is at present taking on new proportions; the American schools are effecting a change in standards, and native ceremonial forms will probably not continue throughout another generation. Not many years hence we shall see the trappings of that religious and artistic climax of the Pueblo Indian's life consigned to stuffy museums and to long, dryly informative reports by eminent ethnologists.