6—

San Diego–Lemon Grove:

Florescence, 1930–1950

In the summers of my youth and adolescence Lemon Grove was a special place. For that was a time of abandon, of back-porch fantasies, and of children's charades through the yards, gates, and trees of the houses that made up that little community. The "hill," an open expanse of chaparral and enticing gullies, was a territorial playground for the marauding chamacos (boys and girls) whose parents and grandparents had settled there. My own parents had been raised in Lemon Grove, although after their marriage they never lived there. But I went often to be with my cousins and paternal grandmother, Ramona Castellanos. The world there was an interlocked reality of neighbors and parientes in which we, as children, were known to be a part. Los Ceseña, Bonillas, Lieras, Alvarez, Castellanos, Nuñez, and others formed the basis of a sociocultural ambiente (environment) that had begun when these and other families sought each other out, settled, and perpetuated the social links that bound their community.

The arrival and early settlement of Baja Californios in the frontera region was a time of movement and family change within the county of San Diego, which at that time stretched from the Pacific to the Colorado basin. In the early years of migration there was great mobility along the international line, but eventually families that had come from the south started settling down. An era began to draw to a close as pioneer migrants gave way to a new generation of offspring that had been born and raised along the migration north as well as in the frontera towns of Calexico and San Diego. The deaths of many pioneers marked the moves of families to San Diego. Nonetheless, some

pioneers survived longer as heads of households and remained significant in the formation of the new communities that arose in San Diego county.

The fiorescence of family interrelations in the town of Lemon Grove introduces a number of new concepts. These include apex families and individuals, incorporation, recurring kin connections, and the perpetuation of family ideology. Each of these concepts can be viewed as a mechanism or process that aided in the cultural development I am describing. Case studies reveal the importance of these processes, but what is less obvious is their derivation from the history, regional affiliation, migration, and settlement of families along the frontera of Alta California. The Lemon Grove phase forms a part of the whole migration process and network development, from the pre-Calmallí era through the frontera period. The discussion focuses on the movement of families out of Calexico and the role of job experiences, kin ties, and family support in migration. I stress here the individual perceptions and behavior of migrants in an effort to document personal histories and present the combined factors that influenced migration and settlement.

Calexico to San Diego

Baja Californio migration along the frontera between San Diego and Calexico began in the first decade of the twentieth century and included migrant movement across the border to the homes of siblings and other kin living in Mexicali, Tijuana, Ensenada, and Tecate. Migration in the early 1920s was characterized by a mobility unmatched in previous or later periods. Hometown visits and visits from southerly kin were common at this time, and the social and kin linkages between individuals and families on both sides of the border became increasingly vivid. These ties encouraged moves from Calexico to the city of San Diego.

Families and individuals migrated principally for economic reasons, but family sanctions in these moves were often equally important. Family communications about the travels and experiences of other Baja Californios and about opportunities for employment in San Diego county enticed other migrants to relocate. Most of the migrants who had worked in Calexico were dissatisfied with their work and the style of life there in general. This dissatisfaction resulted when migrants compared jobs they had held along the mining circuit or in the am -

biente of the southern hometowns with jobs in Calexico, where most worked at unskilled labor.

Manuel Smith:

Kin Ties and Support

Manuel Smith (my great-grandfather) arrived in Calexico from the mining circuit, where he had been an independent leñador . But in Calexico he worked odd jobs and became dependent on the agricultural cycle. In the mining towns he had owned his own mules and collected wood to sell for use in the smelters. In Calexico he picked crops primarily on private ranches. As time passed, Manuel became increasingly disenchanted with the available work and the lack of other possibilities in Calexico and decided to scout the San Diego area for better prospects. Manuel and his son Adalberto traveled to San Diego in a horse-drawn wagon across the Laguna Mountains. In El Cajon they were received by Malvino Smith, a paternal uncle of Manuel's and the son of Antonio Smith, who had left Comondú with Manuel over twenty years before. There they saw rich ranches, the developing city of San Diego, and numerous Baja Californios who had settled the area. They returned to Calexico with plans to move to the San Diego area.

Back in Calexico they gathered their families and as an extended kin group began the trek to San Diego. Three nuclear families joined in the move: Manuel and Apolonia and two unmarried sons; Adalberto (the eldest), his wife, Dolores Salgado, and their children; and Berta Mesa de Bareño, Apolonia's sister, and her family. Los Smith went first to Fresno to earn money for later settlement and remained there,

Diagram 7.

Los Mesa-Smith and los Bareño when they left Calexico for San Diego, c. 1925

Adalberto Smith and Dolores Salgado, Calexico, c. 1918

picking fruit, for about a year. Then with the earned money they moved south to their ultimate destination and settled in Lemon Grove.

Olayo Romero:

Kin and Jobs

Kin were important not only in communicating and offering support to migrants seeking work in San Diego, but in facilitating direct job contacts. In 1925 Olayo Romero and his brother-in-law Levorio Mesa (brother of Apolonia Mesa de Smith, Martina Mesa de Romero, and Berta Mesa de Bareño) went to San Diego to look for work that would allow them to leave Calexico. Olayo had been picking cotton in Calexico and supplementing his income with construction work. Like other migrants he too was unhappy. Olayo left his wife and family in Calexico, unsure of the job possibilities in San Diego. But when he and Levorio arrived in San Diego they met a cousin of Martina and Levorio who gave them a job. Martina reported: "Olayo worked in Lemon Grove. Haven't you seen that rock quarry that's over there? Olayo worked there. My brother Levorio and Olayo came first. I stayed in Calexico. The man who was the manager at the quarry, the mayordomo, was

Diagram 8.

Los Mesa and los Romero

Faracisco Espinosa, a first cousin of mine. And he gave them work." This work allowed Olayo to send for his wife, Martina, and settle in San Diego.

The kin support that was an important factor in the successful moves of los Romero, los Mesa, and los Smith to San Diego came in a variety of ways. In the case of los Romero, kin were directly responsible for securing jobs for the new arrivals. But for los Smith, kin provided more general support in the search for housing and employment. Kin support came in yet another manner to other migrants: adoption and sibling support. The number of offspring in migrant families was generally large and as heads of households aged and died, some left children too young to survive on their own. The strong family cohesion fostered by the institutions of kin extension and kin support provided secure "homes" for these youth. Many children were adopted by older siblings, by aunts and uncles, or by other kin who had settled in San Diego. This problem of orphans signaled the end of an era.

As the era of the first generation of pioneer migrants was coming to a close, a new generation of offspring, born in migration and in the early settlement periods, became increasingly important. A natural unfolding of a new cohort group that had been raised in the frontera took place during this period.

Los Castellanos and los Sotelo:

Adoption and Life-Cycle Transition

In addition to illustrating adoption as a principal mechanism in migration, the following cases show how kin and friendship ties on both sides of the border provided support for migrants. Los Castellanos had close family living in Mexicali and Tijuana, and los Sotelo moved directly from Mexicali to San Diego through similar support. In both these cases the life cycle and the transition of a new migrant cohort group into family leadership is a continuous theme.

The children of Narcisso and Cleofas Castellanos left the Calexico

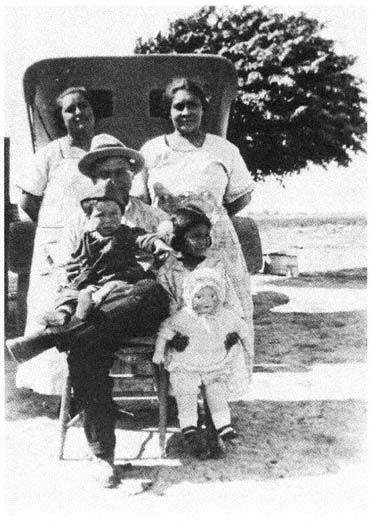

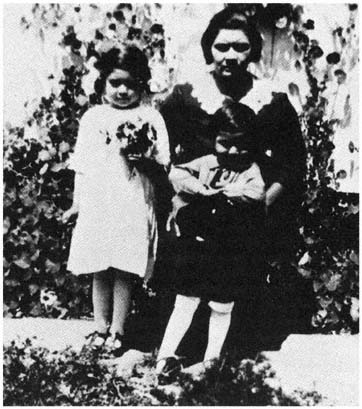

The family of Adalberto Smith in Mexicali visiting the Salgados in 1924,

just before leaving for San Diego. Standing in rear (left to right):

Guadalupe Salgado and Dolores Salgado de Smith. Adalberto sits

holding José with María standing.

(Courtesy of María Smith Alvarez)

Adalberto Smith with his two children, María and José, in Mexicali, 1924.

(Courtesy of María Smith Alvarez)

region when both their parents died (Narcisso in Mexicali in 1918 and Cleofas two years later). They were survived by five unmarried children who had been raised on the frontera and by three married offspring living in the West Coast towns of Ensenada, Tijuana, and San Diego. The family decided that the remaining children should reside in San

Diego with Ramona Castellanos, their eldest sister, and her husband, Ursino Alvarez.

The children left Mexicali through the assistance of Abel (a brother who had married Maria Moore of San Diego), who was working in Tijuana as a chauffeur on the route from San Diego to Tijuana. Abel sent a car to pick up his younger siblings in Mexicali and he met them in Tijuana. Ursino Alvarez also came to Tijuana to lead the children across the border to his and Ramona's house in La Mesa, a small community on San Diego's outskirts. The children remained with Ramona until each of them married. Through her family leadership role, Ramona, as eldest, became the acting head of los Castellanos. She reared her younger siblings and her own children while becoming a principal figure in the Baja Californio network in San Diego.

Diagram 9.

Los Castellanos and los Alvarez in La Mesa, 1920

Los Sotelo were similarly affected by the loss of one of their parents, but rather than receiving support directly from close kin, they were aided by close migrant friends (who are now recognized as distant relatives by Sotelo descendants). Their case illustrates the kinlike support between migrant families which later aided in the development of a tight network of kin.

Don Pancho and Angelina Sotelo arrived in Calexico in 1914. Don Pancho worked in Mexicali, where the family had settled. But when Angelina passed away in 1921, Don Pancho decided to move west. In San Diego, los Sotelo had numerous friends from the mining circuit and from Calexico as well. Los Castellanos, who had been close friends since Las Flores, and los Simpson, friends from Calmallí times, were living in San Diego. When Francisco and the children arrived in San Diego, Guillermo and Artemicia Simpson gave them lodging and sup-

port. They stayed with los Simpson until Francisco found housing in Lemon Grove, where he then settled down.

Diagram 10.

Los Sotelo when they left Calexico-Mexicali for San Diego, c. 1920

These examples help illustrate the similarity of the Calexico-San Diego move to the moves made by migrants along the mining circuit, on early steamers, and in the second-stream migration. Individuals traveled as family and kin groups. They went to areas where kin and friends received and offered them aid and security while they looked for jobs and secured housing. As in previous migratory periods, the prospects of better employment, for those seeking work, was sanctioned by the presence and support of family and friends in the new towns. For those individuals who were forced to leave Calexico and Mexicali to seek support, it was close family and friends in San Diego who provided that security.

The Frontera Towns:

Geographic and Family Connections

Settlement of Baja Californios during the early decades of the twentieth century was not limited to San Diego. Families also settled in Mexicali, Calexico, and Tijuana. Some family members also moved farther south, to Ensenada, another concentration of population.

On the Mexican side Mexicali and Tijuana experienced the most dramatic development and attracted many more settlers than did Ensenada to the south. Counterparts of the U.S. cities of San Diego and Calexico, these Mexican towns also began developing rapidly. Mexicali took on a character of its own as the Mexicali valley grew, and Tijuana developed in response to the dynamic American city across the border.

The settlers of the northern peninsular border towns maintained

close familial ties and relationships with family members and friends in the United States. Some of these individuals eventually settled permanently in San Diego, although many other individuals reentered Mexico to settle at later periods.

The settlement of individuals from the same immediate families, other kin, and friends along both sides of the border perpetuated cross-border movement similar to the unrestricted crossings that had been prominent in the early part of the century. San Diego settlers went to Ensenada, Tecate, Tijuana, and Mexicali to visit siblings and other close kin settled in these towns. And for new migrants seeking entrance into the United States the homes of kin in the Mexican border towns were stopping points where newcomers obtained information and communicated with kin across the border. This pattern of communication, travel, and maintenance of kin ties along the border became more pronounced in the 1930s as Lemon Grove and San Diego became recognized communities of Baja Californios.

Lemon Grove

Lemon Grove, like the other towns singled out in this study, represents a specific time and setting that was important in shaping the settlement and interactions of the families of this study. Although families were settling in a variety of locales in and around San Diego, a nucleus of people settled in Lemon Grove. This nucleus represented the majority of migrant families, including individuals from all phases of migration and with regional ties that kept the Baja Californios together. In the small community of Lemon Grove mining circuit migrants and early steamer and second-stream individuals came together, often fusing several branches of Baja families into a large sociocultural network. Day-to-day contacts between pioneer migrants, migrant offspring, and the new border generation were continual reinforcements of the network's ideological and sociocultural bonds with hometowns, kin in the south, and the peninsula as a whole.

People came to Lemon Grove for a number of economic reasons. Lemon Grove was a small rural community, yet it offered a variety of employment possibilities. The community of Mexicanos was situated in a valley floor surrounded by large citrus orchards and a variety of agricultural fields. The orchards and a packinghouse provided immediate work for most incoming migrants. A railroad, also a job incentive, passed through the community and was the main means of

Map 8.

San Diego County

transport for produce out of the town. Along with these potential employers, a nearby rock quarry employed numerous Baja Californios as miners and laborers. Furthermore, Lemon Grove was only ten miles from San Diego, where there were a variety of opportunities in construction and general labor.

In a real sense Lemon Grove resembled the towns from which migrants had come. It was a self-contained sociocultural community that provided security in the form of available jobs and sociocultural support from kin and friends who had settled and were settling there.

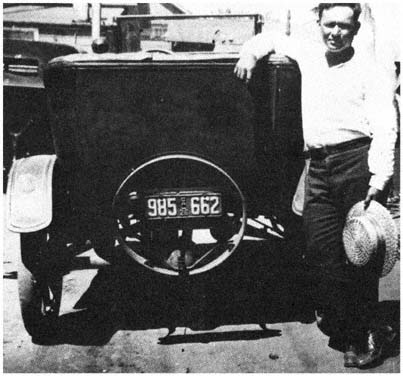

Adalberto Smith in Lemon Grove, 1926

Important life events were shared by the community as a whole, and other kin and friends lived nearby in San Diego and eastward in El Cajon.

Individuals and families who left Calexico and arrived in San Diego and Lemon Grove were received by a number of individuals who had arrived here earlier. Many of these individuals were early steamer and mining circuit migrants. Los Lieras, los Nuñez, los Alvarez, los Castellanos, los Ceseña, los Guilin, and other families had settled in San Diego and were living in Lemon Grove. Abel Alvarez had wed Ramona de las Rosas, originally from San José del Cabo, and settled here. Nicolás Ceseña came to Lemon Grove with his wife, Luisa Chavez, and son. Ramona Castellanos de Alvarez settled here with her own offspring and a number of siblings. Los Gonzales, Smith, Sotelo, Mesa, and a

Dolores Salgado de Smith with her two children, María and José, in

Lemon Grove, 1926.

(Courtesy of María Smith Alvarez)

host of other families came to settle in the little community and raise their families.

Many migrants were attracted to Lemon Grove but found life in the United States far from perfect; as a result, many early settlers decided to return to the peninsula. As always, these return moves fostered the kin and geographic affiliation of Baja families throughout the frontera zone. Most of the returnees did not go back to their hometowns of the cape but chose to remain in the frontera near family. Juana Castellanos married in San Diego but she and her husband

settled in Tijuana. Her brothers Abel and Jesus were already living in the northern peninsula with spouses they had wed in the United States. Los Mesa, Sotelo, and Mesa-Smith all have relatives living in the frontera towns of Baja California. Most of these people tried living in the United States but for a variety of reasons chose to live in Baja California. During the 1930s Hirginia Mesa de Ceseña crossed to San Diego but remained less than a year. She says, "Era muy duro" (It was very hard). The work there was not good and she did not want her husband to work so hard for so little. "Que anda uno robando allá, en tierras ajenas?" (Why should a person steal his living in foreign lands?) Her parents had also crossed but returned to live in Baja too. Her sister Paula went to the United States about 1924 with her husband, Ramon Espinoza, who had siblings and parents in San Diego. They went to Santa Aria, then returned to Tijuana, then reentered the United States to live in Santee, Lakeside, and finally Lemon Grove. They remained a total of four years but ultimately returned because Paula's parents were in Ensenada and the family had all become ill in the United States. They settled in Maneadero, near Ensenada, then in the 1950s moved to Tecate.

Many of the individuals who returned to Baja were pioneer migrants or elder children of the first migrant groups. Older individuals who had continually been disenchanted with jobs and cultural dissonance returned in their later years to be "in Mexico" and on the peninsula. Francisco Becerra returned to live near Ensenada, where he had purchased a ranch. Widowed wives also returned and lived with offspring across the line. In many cases elderly individuals insisted on living in Mexico, fostering movement of offspring into the town of Tijuana.

Lemon Grove represents a phase in which the extension of kin among related and unrelated families reached a peak. In the previous phases, in Calmallí and Calexico, friends and families had come together. They had raised their children, extended compadrazgos, and intermarried, but in San Diego and especially in Lemon Grove these interrelations served as a basis for multiple kinship bonds between families. The network not only grew in numbers but took on a qualitative density previously unmatched. Compadrazgos and marriages increased between families, and several new branches of extended kin were incorporated into the network of relations. Multiple compadrazgos and marriages between the specific set of families provided a multiplication of family bonds and identification recognized by all members.

Everyone was related. They all shared day-to-day experiences, and sociocultural events reaffirmed the identity, parentesco, mutual support, and historical relations of the community.

Migrants were not the sole participants in the formation of close relations, for their children played a significant role in the network development. This cohort shared a number of experiences that helped to solidify their relations as a group. Many attended school together and passed through adolescence as a cohort group. Children were often together at social gatherings of family and community and developed close ties with their own age mates. They were often closely related and their families shared close ties in the community and in work. A strong web of relations bound the community together.

Lemon Grove was the setting, but as in the past, the community was defined by the rich social relations that fostered communal types of bonds and kept migrants together. Despite difficult and sometimes severe socioeconomic and geographic constraints, social relations based on traditional institutions (expressed in new configurations) were the permeating factors that allowed individual expression and the growth of strong ties.

The Processes and Mechanisms of Network Formation

The family interrelations that led to a formal network of kin ties in San Diego are best illustrated by the mechanisms that aided in establishing these relations. A variety of social kin linkages helped produce solidarity between families from Baja California. These linkages are interdependent cogs in a larger sociocultural process that as a systematic whole produced an interconnected web of kin relations. The linkages occurred throughout migration and settlement, but it was only in the frontera that they brought together a number of extended families that otherwise would not have been part of this network.

A number of kin and kinlike linkages fostered by particular families and individuals brought unrelated participants together and promoted the development of kin institutions between families (especially in the case of nonkin). I refer to these particular families as apex individuals and families because of their role in linking the network at various stages of growth. The institutions of compadrazgo, parentesco, and

marriage were the final stages of the linkages in which ties were actually formalized.

Apex Families

Apex families helped develop a formal base of kin ties between previously related and unrelated families. These were important links that brought together the social fields of separate families, primarily through marriage and compadrazgo . These key families first provided a linkage for reciprocity between both settled and arriving migrants. Their own migration experience had introduced them to new families and friends. They became a common link between their own kin and new friends and between their various groups of new friends.

The common cultural and historic background of migrants was the initial base on which the extension of friendship and kin ties was built and deemed socially acceptable. This may seem obvious, but the regional particulars of Baja migrants backgrounds have specific importance in the development of this network. In addition to Mexicanidad[1] and common language, apex families and those they brought together shared a recognized history associated with the peninsula. They shared mutual relations with a number of nonrelated Baja families and brought about face-to-face contact and reciprocity between such families. Reciprocity and friendship eventually led to formal ties of kinship and an extension of the Baja Californio network.[2]

The family of los Simpson illustrates the apex linkage in the maze of closely related families I am describing. This apex linkage was fostered by premigration kin ties, migration friendships, multiple reciprocity and aid offered to friends and relations in the border region.

Los Simpson

The ties of los Simpson with other frontera settlers began in the cape pueblo of San Antonio and developed through the family's migration north. In San Antonio los Simpson knew the family of Loreto Marquez (to whom, descendants state, they were distantly related) before los Marquez went north to Las Flores around 1890.[3] The Simpsons also went on the mining circuit, where they met and united with other families that became part of the network. In Calmallí they met los Castellanos, Sotelo, Smith, Bolume, and others. Los Simpson eventually went to San Fernando, then crossed the border at Campo and headed east to Calexico.

Diagram 11.

Initial reciprocity

The Simpsons' assistance to families entering the frontera shows the mutual aid and kinlike support they extended to other mining families. In Calexico they offered their home and assistance to the family of Don Pancho Sotelo until the new arrivals found work in Mexicali and moved across the border. In the same period Narcisso Castellanos, his wife Cleofas, and their children stayed with Guillermo and Artemicia Simpson until they too found work. The mutual friendships of the mining circuit experience were further enhanced not solely by the assistance and support offered by the Simpsons but also through the social sentiment and solidarity of mutual friendship between these families.

In a pattern now familiar the Simpsons left Calexico, traveled west, and settled in San Diego. There, once again, they received Pancho Sotelo and his family, who had left Calexico and now sought help in settling in San Diego. The Sotelos remained in the Simpson household until Don Pancho got a job and moved to Lemon Grove.

The kin linkages of the Simpsons are also illustrative of their apex role in the tight web of interrelations among the Baja Californio population. Los Sotelo speak about their kin relation to los Simpson. Descendants speak of this as a distant tie that became significant after migration. Confianza and friendships derived from the migration experience appear to be the important link that established close ties between the two families. Los Sotelo are related to los Simpson through Señora Artemicia Simpson (whom Guillermo met and wed in San Ignacio). Don Francisco's wife Angelina was Sra. Artemicia's maternal

Diagram 12.

The kin ties of los Simpson and los Sotelo

aunt. These links were further strengthened among second-generation frontera offspring. The close friendships of the Sotelos and Castellanos provided a base for the marriage between offspring of these families. Refugio Sotelo and Tiburcio Castellanos were wed in San Diego, and when Guillermo Simpson's son (Guillermo II) married and had children, los Castellanos served as padrinos de bautismo (baptismal godparents), forming a compadrazgo relationship between these families. The linkage does not stop here. Guillermo Simpson (II) married Sarah Fernandez, whose family had come north from Santa Rosalía during

Diagram 13.

The compadrazgo relationship between los Castellanos-Sotelo

and los Simpson

the mining circuit period. This link united another network of families that had become acquainted on the mining circuit but had not become formally linked. Sarah Fernandez's sister Flora married Manuel Smith II, son of Apolonia Mesa and Manuel Smith from Comondú. Furthermore, the Fernandez family can be traced directly to the Mesas of Comondú, who are direct descendants of Apolonia Mesa-Smith.

The compadrazgo relationships between the Simpsons and the Castellanos-Sotelos, along with the marriage of Guillermo Simpson to Flora Fernandez, brought two extended families together into a web of relations. This network was further cemented by a series of compadraz -

Diagram 14.

The Simpson linkage to Castellanos-Sotelo and Fernandez-Smith

gos and marriages. The most obvious and important is the second marriage of Don Francisco Sotelo himself. Don Francisco married Sarah Fernandez de Simpson's maternal aunt (Refugio) in the late 1920s (see diagram 15).

This complicated set of linkages illustrates the multiple sets of interfamily relations in Calexico and San Diego during the 1920s. This example is only a skeletal outline of the matrix of interpersonal relations between kin and nonkin in the frontera region which produced social fields among these families. The Simpsons, like other apex families, provided key links in marriages and compadrazgos which helped form a tight social community in San Diego during the 1930s.

Apex families and individuals play a role similar to that of centralizing women (see the history of the Gomez family in Lomnitz 1978). Like centralizing women, apex families provided emotional centrality and leadership for a variety of network members. This emotional sharing was based primarily on mutual experiences, confianza, parentesco, and the recognition of a similar sociocultural standing (class). This sentiment was further emphasized in the mutual aid and reciprocity of relations and extension of kinship between network members. Unlike the patron-client relationships discussed by Lomnitz, the role of apex families remains at the level of mutual aid; there are no "big men" of upper class and better economic standing who, because of class standing, become apex individuals. During frontera era settlement in San Diego, the network was a homogeneous class composed of laborers and small entrepreneurs. Indeed, economic aid and reciprocity was an important component of network development, but shared experiences, kin ties, and acquaintances that fostered parentesco and the mutual responsibility such sentiment requires were of prime importance. Apex families, like apex individuals, are also differentiated from

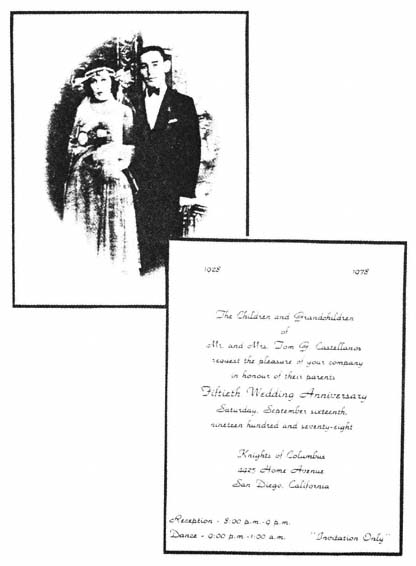

Family Invitation to Fiftieth Wedding Anniversary of Refugio Sotelo and

Tiburcio Castellanos

centralizing personalities because they aid in the formation of key kin linkages between a variety of families. The Simpsons clearly illustrate such linkages through various generations and members of their family.

Apex Individuals

Apex individuals are key individuals who, through their own marriages, compadrazgo ties, and experiences created specific network linkages within a large set of families.

Refugio Gonzales de Sotelo

Refugio Gonzales was born in 1888 in San José de Magdalena, a small town near Santa Rosalía, but after marriage she traveled north and eventually settled in Lemon Grove. Refugio was a direct descendant of the Mesas of Comondú, but she was raised primarily in Santa Rosalía, where her father worked in the mines of El Boleo. In 1916 she married Albino Vargas, a captain of small boats who commuted between various gulf ports, and the couple went to live in Guaymas, across the gulf. In the next decade she and her immediate family moved north to Nogales, where her husband died. She then crossed the border with her children and traveled first to Los Angeles, where she remained with her mother-in-law until 1928; then she moved south to Lemon Grove.

Refugio came to Lemon Grove because her parents (who had arrived in 1926 from Cananea) and a sister, Balvina Fernandez, were there. Balvina had married Antonio Fernandez (before Refugio married) and traveled north through the mining circuit to San Diego.

When Refugio came to Lemon Grove, she met a variety of other Baja Californios. Among the families and individuals she met was Francisco Sotelo, whom she married one year later, establishing a network tie between two family extensions that had been acquainted in the migration north as well as in Lemon Grove. The Sotelos were part of the network that included los Castellanos, Alvarez, Simpson, and other closely related families. Refugio's marriage formally served to link this network with the Mesa-Smiths. Although these families had known each other from other settlement periods, this linkage, like others between these family groups, helped formalize the previous acquaintances and interrelationships. The close ties of the Sotelo-Castellanos become evident in the marriages of Francisco Sotelo's daughters into the Castellanos family.

Diagram 15.

The linkage of Mesa-Smiths to Sotelo-Castellanos

Refugio Sotelo's linkage of the families also came through compadrazgo relations as well as through marriage. Tiburcio Castellanos and his niece Mercedes baptized Refugio's first son. This example illustrates only a fraction of the interconnections between these families.

Guadalupe Bolume

Guadalupe Bolume is a central figure in the creation of qualitative and dense relationships between Baja Californio families. Her experience in the mining circuit became a base for the extension of kin relations in her own marriage to a mining circuit migrant as well as in marriages between her own offspring and other Baja Californios who settled in San Diego. Her offspring married into families of original Baja pioneer migrants. Diagram 16 illustrates her central position, through her offspring, in formally bringing together these families. These marriages formally linking families were more than just expressions of solidarity between Baja migrants. The individuals of these families were close friends and were proud of the sentiment they shared. Romances and weddings developed from their closeness as did compadrazgos . Formal ties became ways to express close sentiment and relations between individuals and families. Such ties not only brought individuals together but they also formalized and ritualized social interactions in a number of social and cultural events practiced by these families. Baptisms, marriages, birthday celebrations, funerals, and U.S. and Mexican holidays alike became large network social events of kin whose roots lay in Baja California and the migration trail.

Apex individuals, then, like apex families, were not solely bringing together migrant families through marriage and compadrazgo . As

Diagram 16.

Marriage ties of Guadalupe Bolume's offspring showing network linkages and family origin in migration

central figures in the network they helped produce continuing ties that had begun in the migration process. These respected individuals continue to be recognized catalysts among the community of Baja families in San Diego.

The tight web of relations fostered by marriages between families was further intensified by the incorporation of non-Baja Californio families into the network. This took place in Calexico as well as in San Diego, but it was in Lemon Grove that such incorporation took on a specific role in maintaining interrelations of the Baja Californio community.

Incorporation

As Baja Californios crossed the border and settled in San Diego, other Mexicanos arrived and became part of the migrant community. Immigration from mainland Mexico had diminished after the turn of the century compared to the influx of mainlanders who had come in the decades of the revolution, when transportation was developing in the northern sections of the mainland. Nonetheless, some individuals and families continued to arrive and settle in San Diego. The sparse immigrant population congregated in a variety of neighborhoods, but Lemon Grove was the most prominent settling place. Some of these mainland families became incorporated into the network of Baja Californios.

Incorporation can be defined as the recruitment of (in this case, mainland) families which promoted boundary maintenance and internal cohesion of the Baja Californio network. The term recruitment is used loosely here, for Baja Californios did not actively seek out new families. Incorporation occurred as a natural process among individuals who shared a common language and culture. The absorption of new families served to pull specific families into the network and helped to solidify and intensify interrelations among Baja Californios.

Incorporated families united various Baja California families. Marriages between members of mainland families and individuals from a variety of Baja families created overlapping kindreds bringing Baja Californios together in formal kin connections. This is best illustrated through genealogical examples of intermarriages. The cases of los Bonilla and los Oyos are two such examples. Both the Bonilla and Oyos families came directly from the Mexican mainland and settled in Lemon Grove, where they met and shared daily experiences with the other members of that community.

Los Bonilla

Los Bonilla provided a base for a number of linkages between families settled in Lemon Grove. Los Bonilla were among the first families in Lemon Grove, settling there during the early decades of the century, before it became a Mexicano community. They lived within a quarter-mile radius of numerous Alvarez, Ceseña, Castellanos, Guilin, Sotelo, and Lieras family members who made up the basis of the network. Nine women were born to the Bonillas and were raised and socialized with Baja Californios and other Mexicanos.

The marriages of the Bonilla children reveal the close ties this family maintained with Baja Californios as well as the strengthened ties that developed between Baja Californios as a result of these marriages. Marriages between Bonillas and Castellanos, Bonillas and Ceseñas, Bonillas and Alvarezes, Bonillas and Gonzales-Nuñezes served to unite these families in formal relationships. Diagram 17 charts these marriage ties and the origins of intermarrying family. The immediate result

Diagram 17.

Bonilla marriage ties and origins of spouses' families

of such ties was the creation of formal affinal bonds between all these families and the development of a large kindred of interrelated Baja families of which offspring were members. Additional marriages reemphasized these ties. Alvarez married Smith (Comondú), Castellanos married Sotelo. These ties help to illustrate a complex set of inter-family relations that were in part created through incorporation. In addition to marriage ties, compadrazgo between these families was similarly multiple.

Incorporation can also be distinguished in later generations. The

Diagram 18.

Continuing marriages of network offspring

marriages between los Oyos and los Sotelo-Castellanos is one such example that illustrates the maintenance of family solidarity and intra-family relations.

Diagram 19.

Castellanos-Oyos ties

Certainly such ties were not planned; nor was the sole purpose of these marriages to maintain tight family bonds within and between familia from Baja California. Los Oyos, los Bonilla, and other families had become close, respected friends who shared and contributed to the establishment of a strong sociocultural community of Mexicanos in San Diego.

The mechanisms I have discussed thus far were significant components in the formation of a strong network of kin relations among the families of this study. The apex families and individuals served to formally unite not only dyads (in the form of families) but myriads of families who were already familiar and shared bonds. Incorporation was equally important as a middle-ground process, bringing together a wide set of families who shared regional background, migration, and settlement. A similar mechanism is the tie between families resulting from recurring kin connections.

Recurring Kin Connections

The processes I have been describing are manifest in a specific pattern of recurring kin connections which becomes evident when viewed over several generations. Recurring kin connections, along with the other kin processes and the mechanisms of incorporation and apex families, aid in the identification of a true sociocultural pattern. Viewed in this way, the network is not solely an arbitrary set of relations that brings together a group of families with similar histories. It is a sociocultural pattern identified by a specific history, specific institutions, and shared sociocultural behavior.

Recurring kin connections are specific kin ties that developed in Baja California and recurred after the families' migration to the frontera zone. Such ties are best viewed in marriage ties between families over several generations and are evident between descendants who intermarried in the U.S. a half century and as much as a century later. When viewed in relation to the migration experience, these recurring ties encompass a field of border families that previously shared relations or were closely linked through extended or affinal kin ties. Ties of this sort not only united two family branches but they helped sustain and reinforce kin and social relations while creating new bonds based on contemporary sentiment and mutual support. The resulting pattern of linkages help create and solidify the community in San Diego (see diagram 20).

Family ties in San Diego in the early twentieth century intensified for a number of reasons, for extensions of kin relationships coincided with a dramatic period of change. New social forces were shaping international attitudes and U.S. and Mexican government relationships as well as the face-to-face relations of immigrants and natives who settled in the border zone.

The impact of the border environment, especially for those who settled in the U.S., was a major force intensifying the mutual help and kin ties that led to a discernible family network. Across the border in the nearby towns of Tijuana, Tecate, Mexicali, and Ensenada, no similar definable network developed. Early migrant pioneers from the south did intermarry, but once the Baja families settled in the northern peninsula they began to intermarry with other Mexicanos from the mainland. During this period Tijuana and Mexicali were propelled into the limelight as urban nuclei and receiving zones for one of the greatest migrations in Mexican history.

The families that returned to the peninsula and those that had remained in the Mexican border towns did not share the need to perpetuate a sociocultural identity because they were not threatened by a foreign culture. They settled in Mexican towns, intermarried with Mexicans in a natural fashion, and extended kin institutions among other northern settlers. In San Diego, however, individuals were in a non-Mexican environment and had to seek out other Mexicanos and in this case trusted kin and acquaintances to be assured of successful sociocultural survival. The relationship of experience, mutual kin, regional ties, and history surfaced as a common ground for mutual aid and support in a precarious environment. Numerous family departures from the United States bear witness to the problems of cultural dissonance as do the marriage partners chosen among San Diego families. Among los Sotelo, the two children who remained with Don Pancho in Lemon Grove married into a Baja California family that had been their persistent companion from the days of the mining circuit (los Castellanos). The other four children who were not in Lemon Grove married Mexicanos from the mainland. Two had remained in Mexico before marrying, the third had gone to live in Tijuana before marrying, and the fourth individual had traveled north to San Pedro where he also married a mainland Mexicana. The history of other families reveals similar examples. More evidence is manifest in the marriages of pioneer migrant offspring who returned to Mexico. In these cases marriage to native Baja Californios was rare. Communities in Mexico were and are settlements of regionally integrated Mexicanos.

My purpose here is not to prove the uniqueness of Baja Californios in the United States but to show how these people used Mexicano family institutions within new and threatening sociocultural circumstances. The creative adaptability of these institutions and people allowed sociocultural survival and long-range cultural maintenance. Like

Diagram 20.

Prominent examples of recurring kin connections in the family network, 1840–1940

other migrant communities, Baja Californios illustrate the propensity and flexibility of cultural institutions to preserve and create new patterns without creating social disequilibrium.

Family Ideology

Regional ties, hometown sentiment, and the relationships based on such geographic bases all contribute to a body of ideas shared by Baja California migrants. This body of ideas as an ideology is specific to individuals and families who arrived and settled along the frontera during and after the turn of the century. As a manifestation of the regional ties and experiences shared by Baja Californios the ethos was internalized and became a mechanism and promoted the development of the network. This ideology is identified and expressed in both communication and behavior and is perhaps the strongest identifiable sentiment that had been expressed by pioneers and their offspring. People speak of the peninsula in terms of the early individuals who passed through specific geographic areas and in terms of hometowns, friends, and kin. Los Smith, los McLish, los Simpson, los Green are names important in lore particular to the peninsula and elicit tales of peninsular history, early settlement in San Diego, and continuing ties with the peninsula. Tales and manifestations of kin meeting kin, of travels in the peninsula, of hardships, and of nationality combine to form an ideology that stems not only from the main Mexican cultural background of Baja Californios but from the shared experiences of migration and settlement. The ideology, in part, strengthens ties to the peninsula but at the same time is unique in strengthening intrafamily recognition and identity. Ideology is expressed in a variety of ways. It is expressed in patriotism to Mexico, in nationality, in the choice to have children born on the peninsula, and in family lore.

Mexican nationality and patriotism is perhaps the clearest early manifestation of this ideology. Many pioneer migrants, although settled and working in the United States, maintained strong sentiment for the peninsula. This can be viewed as Mexicanidad, but overall patterns and expressions by individuals indicate the importance of the peninsula in such manifestations. In one case a pioneer who had arrived in San Diego in 1907 returned to the peninsula in 1911 when an American-led group of Industrial Workers of the World invaded Baja California. He returned to defend his country against the sin verguenzas (shameless) Wobblies who had entered with the intention of creating an inde-

pendent socialist republic. He joined the Mexican army and served as a guide in his home area. When the invasion had been repulsed, he returned to San Diego. On another occasion he returned and volunteered for the Mexican army when the United States marines landed in Vera Cruz, because, as he states, he did not want Baja California to fall into U.S. hands like Texas had.

The births of the Castellanos children can be interpreted as another ideological statement (see chapter 4). Each of Narcisso's nine children was born on the peninsula. Even after Narcisso immigrated to San Diego, he insisted that the family return for the births of the last two offspring. So in 1906 and 1908 the family returned to the mining circuit. To this day Tiburcio, who was born in Julio César, has proudly retained his citizenship, although he has spent only four years of his life in Mexico and continues to live in Lemon Grove.

Vicente Sepulveda is another example of how patriotism helped in maintaining an attachment to the peninsula. Vicente worked at the border station of Mexicali for the Mexican government, but he lived with his wife, Guadalupe Salgado, in Calexico. In 1911, when the Wobblies crossed the line to invade the peninsula, Vicente joined and fought against the filibusteros with the Mexican forces of Celso Vega. He was seriously wounded at the battle of Rancho de Little and taken to Mexicali, where Guadalupe met him and took him across the border into Calexico, where he died. That Vicente died in Calexico did not diminish the significance of his act, for the city was considered part of the frontera, regardless of the political boundary and official recognition of territoriality. From the family's perspective Vicente died defending Mexico against a group of filibustering Americans[4] from the north. Years later in the sixties Vicente's death, along with others' who died defending the peninsula, was commemorated yearly as a patriotic effort. Vicente's only daughter, Maria Sepulveda, crossed yearly from San Diego to partake in the ceremonies, keeping not only an individual's history alive but the ties of the frontera as well.

Family lore is intricately bound with the places and the history of the peninsula. Stories of past experiences have become important evidence of kin connections as well as romantic reminiscences of bygone days. Second and third generations recount stories of early pioneers' experiences in their hometowns and in Calmallí and Las Flores. Alfredo Becerra speaks of his father Vicente's close acquaintance with Guadalupe Bolume in Calmallí, that they had danced there together, and that Vicente had provided music (guitar) for close mining

friends. In San Diego Vicente Becerra played his guitar again for Guadalupe Bolume when she wed another of his close friends, Jesus Castellanos. Nicolás Ceseña speaks of the early Californias, the entrance of the French into San José del Cabo, and the good people from the cape: "When the French arrived in San José, they found potable water and said 'Where there is a running stream there are decent human beings.'"

Baja Californios and their descendants are aware of the unique populations that arrived in the peninsula and have made this part of their lore. The tales of blue-eyed Smiths crossing the line amazing both Mexicanos and Americanos is repeated with great humor. Encounters in mid-peninsular travels with Americans produce similar tales. Manuel Smith (III) and Guillermo Simpson (III), who both rerum frequently to the peninsula, jokingly relate meeting a jeepload of Americans. As they approached on horseback dressed in ranchero fashion they introduced themselves, to the amazement of the jeep travelers. Interkin connections are also told with great relish. One story tells of a mid-peninsula traveler who is carrying mail on horseback and who meets a group of frontera Smiths. After a short period they discover that the letter carrier, the person to whom the mail is to be delivered, and the frontera individuals are all Smiths and intimately related through ancestors from Comondú. Such tales are not uncommon. Individuals speak proudly of their history, of the kinship with the peninsula and to the families that have a long history there.

This oral history constitutes an ideology that is shared and perpetuated among families and serves to help maintain group identity and solidarity. And like the other mechanisms, ideology also functions as a basis for the extension of kin and kin relations among frontera migrants and settlers, for the network is a cultural system that shares unique regional traits manifested in family institutions.