PART II

Chapter 4

"Ordinary Buying and Selling"

The new economic policy turned Moscow into a vast market place. Trade became the new religion. Shops and stores sprang up overnight, mysteriously stacked with delicacies Russia had not seen for years. Large quantities of butter, cheese, and meat were displayed for sale; pastry, rare fruit, and sweets of every variety were to be purchased. . . . Men, women, and children with pinched faces and hungry eyes stood about gazing into the windows and discussing the great miracle: what was but yesterday considered a heinous offense was now flaunted before them in an open and legal manner.

—Emma Goldman

By the end of NEP's first summer, it seemed to many observers that Russia was awash in private trade, especially in comparison to the lean years of War Communism. After moderate growth in the spring and summer of 1921, private trade spread rapidly following a decree from the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom), issued on August 9, that permitted small-scale private manufacturing and the free sale of goods produced by such operations. Two months later, Lenin conceded that the state plan to establish direct commodity exchange with the peasantry had been elbowed aside by "ordinary buying and selling."[1] Armand Hammer, who began his long business relationship with the Soviet Union in 1921, was amazed at the changes that had taken place in Moscow when he returned at the end of August, following a trip to the Urals:

I had been away little more than a month, but short as the time was, I rubbed my eyes in astonishment. Was this Moscow, the city of squalor and sadness, that I had left? Now the streets that had been so deserted were througed with people. Everyone seemed in a hurry, full of purpose, with eager faces. Everywhere one saw workmen tearing down the boarding from the fronts of stores, repairing broken windows, painting, plastering. From high-piled wagons goods were being unloaded into the stores. Everywhere one heard

the sound of hammering. My fellow travelers, no less surprised than I, made inquiries. "NEP, NEP," was the answer.[2]

Many other witnesses recorded similar impressions, including the New York Times correspondent in Moscow, who wrote in September that the city had recently appeared every bit as barren and dilapidated as many French towns at the end of the First World War. "Now, under the stimulus of the new decrees that are constantly being issued to regulate the changed economic policy, and under the liberty of private trading, shops, restaurants, and even cafés are being opened in all directions."[3] A Canadian living in Moscow during the first years of NEP observed ironically that some foreigners who arrived in the Soviet Union after this revival of trade considered Moscow rather shabby and run-down. But those who had known the city during War Communism, he explained, had a different perspective and were dazzled by the changes NEP produced: "The New Economic Policy had gone further than many dared hope. The Terror had largely vanished. The shops had all reopened, and the streets were now crowded until late at night with people. Even the gaping roadways, always bad in Moscow, were being repaired."[4]

Trade was without question the Nepmen's most important occupation in the newly legalized realm of business, both in terms of rubles and in terms of the number of people involved. Private individuals generally preferred trading to other endeavors such as manufacturing because (1) comparatively little capital was needed to begin trading; (2) the return on investment was generally rapid, an important consideration when long-term business prospects seemed uncertain at best; (3) traders (particularly small-scale vendors) were mobile and better able to avoid taxes, licenses, and other forms of state regulation than were manufacturers; and (4) little business experience was necessary to begin petty trading.[5]

Nearly all private trade was of simple, basic consumer goods. Such merchandise required relatively small amounts of capital to produce and was much in demand, given the widespread shortages of so many necessities. Food—fresh meat, vegetables, dairy products, grains, bread, and processed items—was the commodity most frequently handled by private traders. Particularly in the first months of NEP, the food shortages in most cities and towns ensured that virtually anything edible could be profitably marketed. But even in later years, food represented 40 to 50 percent of the volume of private trade. Most remaining private sales involved textile products and leather goods, such as boots and shoes,

and other manufactured (often handicraft) items of use in and around the home.[6]

For licensing and tax purposes, the government divided private traders into ranks according to the nature and size of their business—the higher the rank, the higher the license fee. In the summer of 1921, as we have seen, there were three broad ranks of trade, but as the size and diversity of private enterprises increased, so did the number of categories. Two more were added in 1922, followed by a more detailed definition of the five categories in 1923 and the addition of a sixth in 1926.[7] State agencies used these categories in their statistical surveys of private trade, and consequently much of the available data concerning the Nepmen are expressed in these terms. Therefore, a brief summary of the types of activity included in each trade rank might prove helpful before proceeding with an analysis of the characteristics of private trade.

On the basis of the lengthy definitions in the decree of 1922, the five trade ranks may be described as follows.

|

The state tried to fill the gaps in its definitions by classifying all firms that did not fit into any category as rank III operations unless their monthly business was less than 300 rubles, in which case they were assigned to rank II. Somewhat more detailed definitions of the trade ranks were included in subsequent decrees, but the main characteristics of each category remained unchanged throughout the rest of NEP.[8]

In the first months of NEP private trade was confined almost exclusively to petty transactions in markets and bazaars, nothing more sophisticated or elaborate than had existed illegally during War Communism.[9] People from many different professions and walks of life—factory workers, intellectuals, demobilized soldiers, prewar merchants, artisans, invalids, peasants, and a large number of housewives—plunged into trade (often the barter of personal possessions) in quest of food, clothing, and fuel. At this time there was no effective network of state inspectors to register and tax private traders, and this was all the encouragement many hungry people needed to try their hand at trade.[10] As a fieldworker for the American Mennonite famine relief organization reported from the Ukraine in November:

When the people had no more bread their only recourse was to exchange some of their clothing, their furniture or their farming implements for food. Everything imaginable was carried to the "Toltchok" (the "jostling-place" in the village bazaar, where people exchanged or sold personal belongings). The market was soon glutted with such things, so that beds and dressers were selling for ten or fifteen pounds of barley flour, a ten horse-power naptha motor for ten bushels of barley, and other things in proportion.[11]

A traveler in Siberia during the winter of 1921-22 noticed that "many of the homes of Irkutsk were largely empty. The families had sold their furniture bit by bit to the peasants for food."[12]

Private traders often worked only part time or on their days off from other occupations, traveling to rural markets to buy food from the peasants, either for their own families or for resale in the cities. This type of trade, called bagging (meshochnichestvo ), became an extremely important conduit of food to the residents of cities and towns in 1921 and 1922. Because of bagging's small-scale, itinerant nature and the inability of nascent state agencies to monitor such activity at the beginning of NEP, there are almost no statistics on the volume of such trade or the number of bagmen—one source claims that over 200,000 were riding the rails by the middle of April 1921 in the Ukraine alone. In any case, many people were struck by the crowds of bagmen traveling to and from food-producing regions. The chairman of the Cheliabinsk Guberniia

Party Executive Committee reported in April that "a huge wave of bagmen, impossible to control, has flooded Cheliabinsk guberniia and Siberia." Similar telegrams were sent by officials in other cities located in the grain belt.[13]

The railroad was generally the only means of transportation for bagmen, and they often engulfed an entire train like a legion of ants. An Izvestiia correspondent wrote in May:

In the Ukraine bagging has assumed completely inappropriate forms. That which one sees at small stations has blossomed doubly in Kiev itself.

A sort of gray caterpillar moves along the rails—this is the train, completely covered with a gray mass of bagmen. Under them neither the cars, nor the engine, nor the roofs, nor the footsteps, nor the spaces between the cars are visible. Every space is occupied, filled in. But as the train slows down in its approach to the Kiev station, its gray skin begins to slip off.[14]

The authorities tried to prevent such travel, but without complete success. An American Relief Administration official on a trip from Voronezh to Moscow in March 1922 marveled at the tenacity of the bagmen. No matter how many times the police chased them off the cars, they managed to clamber back on again. As a result, there were more people hanging on outside the cars than there were inside.[15] As the food short-age worsened, desperation drove people of all sorts, from professors to children, into the sea of bagmen.[16] The competition among these traders was understandably fierce, with little to prevent the strong from seizing the provisions of the weak.

Railwaymen were in an ideal position to conduct this sort of trade, since they made daily trips to and from the countryside. It was comparatively simple for them to transport various commodities from the towns to exchange for food with the peasants, and then sell the food for a handsome profit back in the towns.

This plan [a traveler observed] was general among the railwaymen. One guard on a through express showed me his stock. He took his wife with him, occupying a big compartment, although a number of passengers had been left behind for lack of room. The lavatory attached to the compartment was stocked up. Salt was this guard's medium of exchange. The country people were clamorous for salt. His wife did the bargaining with the peasants, so many pounds of salt for a goose, so many for a suckling pig, and so on.[17]

As in this illustration, nearly all trade between bagmen and peasants assumed the form of barter. The main reason was that most sellers refused to accept currency rendered worthless by the breathtaking inflation that marked NEP's infancy. Such concerns were, of course, not limited to the

bagmen and peasantry. An article in the Commissariat of Finance journal estimated that barter accounted for fully 50 to 70 percent of all trade in Russia during the first half of 1921/22.[18]

There was virtually no private trade from large, permanent shops at the beginning of NEP. For one thing, relatively few people possessed the necessary resources and expertise. But the most important factor was uncertainty that NEP had actually been adopted "seriously and for a long time," as Lenin claimed. With the harsh experience of War Communism a recent memory and the Bolsheviks' express desire in the spring of 1921 to limit private trade to local barter, prospective shopkeepers did not rush to test the waters. An old trader told an acquaintance that he suspected NEP was a ploy on the part of the Cheka (secret police) to entice merchants to reveal their hidden goods and money. If they took the bait, he feared, the police would seize their merchandise and imprison them. In this spirit, individuals capable of conducting larger-scale trade generally elected to remain on the sidelines until they were certain of War Communism's demise.[19]

Gradually, though, during the course of 1922, entrepreneurs became convinced that permanent stores would be tolerated, and the number of these establishments grew steadily.[20] The lingering uncertainty of some Nepmen was evident in their tendency to initially give their businesses official, "Soviet" names such as Snabprodukt (Produce Supply) and organize them, ostensible, as cooperatives. As time went by, they began to conduct business more openly under their own names and transformed the "cooperatives" into private enterprises.[21] Meanwhile, many of the "amateur" petty street hawkers and bagmen succumbed to the twin blows of competition from the growing number of permanent shops and the taxes that the Bolsheviks began to levy on private traders.[22] From the summer of 1922 to the summer of 1923 the number of licensed private shops increased 36 percent in rank III, 70 percent in rank IV, and 188 percent in rank V, whereas the number of petty private traders in ranks I and II fell by 23 and 8 percent, respectively.[23] Similar trends are evident in figures covering a slightly different time period (see table 1). These developments occurred first in the large cities, with the countryside lagging behind by several months or even a year in areas ravaged by the famine of 1921-22. During the first third of 1922, for example, the

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

number of permanent private stores swelled by 83 percent in Moscow, rising from 2,900 to 5,300. At the same time, provincial newspaper correspondents reported from many localities, particularly in the devastated middle Volga region, that large-scale private trade was virtually nonexistent.[24]

The number of Nepmen who had prerevolutionary business experience as merchants or store employees increased after 1921, since these were generally the people opening the larger shops.[25] The dominance of experienced traders in the upper ranks is evident in figures (table 2) collected by the Commissariat of Domestic Trade during an investigation in 1927 of the Nepmen's social origins. As one might expect, the larger a merchant's operation, the more likely he was to have been active previously in trade. Vendors with little or no business experience—most often peasants, workers, and housewives—were concentrated in the first two ranks.

Around the turn of the century the Russian business elite (krupnaia burzhuaziia in Soviet studies) numbered approximately 1.5 million merchants, financiers, and industrial magnates.[26] Nearly all these people lost or closed their businesses, emigrated, or perished during the onslaughts of the Revolution and civil war. One exception was Semen Pliatskii, who had been a millionaire metal trader in St. Petersburg. Instead of emigrating after the Revolution, he chose to remain and to work for the state, surviving two arrests by the Cheka during War Communism. Following the introduction of NEP he set out on his own, first as a buyer and seller of scrap metal and later as a supplier of industrial products ranging from office supplies to lead pipe. He had a knack for acquiring even scarce commodities by hook or by crook. Here his many connections

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

with state agencies, often established with bribes, undoubtedly helped. As Victor Serge put it: "This Balzacian man of affairs has floated companies by the dozen, bribed officials in every single department—and he is not shot, because basically he is indispensable: he keeps everything going." It was not unusual for state enterprises to give Pliatskii's orders preferential treatment over those of other state agencies. Before long, he had become a millionaire again.[27] But the ranks of the "new bourgeoisie" contained few prewar merchants of Pliatskii's stature. Nearly all the Nepmen with previous trading experience had been nothing more than small-scale entrepreneurs or shop employees before the Revolution.[28]

After the uncertainty accompanying the introduction of NEP had been dispelled, and trade assumed a comparatively normal form, the distribution of Nepmen in the various trade ranks was roughly as follows through 1926. Half of all licensed private traders belonged to rank II, numbering between 180,000 and 260,000 persons, depending on the year and the season (as a rule, fewer people engaged in trade during the winter). Approximately one quarter (90,000 to 140,000) of all private trade licenses were held by rank III traders, and slightly over one fifth (70,000 to 120,000) belonged to rank I traders. The remaining three or four percent were issued mainly to Nepmen in the fourth rank (8,000 to 18,000), with rank V private traders accounting for less than 1 percent (1,600 to 4,000) of the total.[29] Thus, over 70 percent of all private traders—ranks I and II—did not operate from permanent shops (more specifically, buildings designed for the customer to enter), but traded

mainly in the streets, market squares, and bazaars, either from booths or stalls or out in the open. Many small-scale traders avoided registration, and their actual number was thus undoubtedly even greater than the figure presented above.[30]

Private traders in rank III, however, were responsible for a volume of sales roughly twice that of rank II Nepmen, according to data for the period from 1923 to 1926—even though there were twice as many traders in rank II as in rank III. This, of course, is because the permanent shops of rank III were considerably larger operations than the businesses of rank II vendors in the open markets. In fact, the Nepmen of ranks IV and V, who, taken together, numbered no more than 8 percent of the private traders in rank II, accounted for a significantly larger sales volume than did the rank II traders (from 16 to 77 percent larger for the various six-month segments of this period). Data of this sort are not available for rank I Nepmen, though their sales must have been much less than those of private traders in rank II, for the latter were over twice as numerous and ran larger businesses.[31]

As one might conclude from these figures, more private capital was invested in rank III enterprises than in those of any other rank. In fact, data for 1924/25 indicate that the investment in rank III private trade (452.3 million rubles) was nearly as much as the capital invested in the other four ranks combined (454.5 million rubles). Also significant is that large firms in ranks IV and V, which accounted for only 3 or 4 percent of all private trading licenses, together utilized over one third of all private trade capital (138.1 million rubles for rank IV and 194 million rubles for rank V); whereas only 13 percent (114 million rubles) of private trade capital was invested in rank II, and less than 1 percent (8.4 million rubles) in rank I.[32]

This regeneration of larger, permanent private shops was impressive, but even during the peak of the Nepmen's activity in 1925/26, private trade did not regain its prewar level of sophistication. In the years before the First World War, nearly two of every three private trading operations were fixed, permanent shops, whereas in 1925 only about one quarter of all private traders worked in such facilities. The remaining 75 percent, as just mentioned, carried their wares around with them, selling from wagons, booths, tents, trays, and so on, usually in market squares and bazaars. Thus, although there were more urban private traders in the middle of NEP than before the war, their volume of sales was only about 40 percent of prewar urban sales. Rural private traders in 1924/25

numbered only about 20 percent of their prewar counterparts—the figure rose to about 50 percent by 1926/27—and accounted for only about 13 percent of the prewar volume of rural trade.[33]

The predominance of small-scale trade was the result of a number of factors. Even in relatively prosperous times it was impossible for most Nepmen to raise the capital necessary for a large wholesale or retail firm, while modest operations could survive on a small volume of sales and, generally, were less dependent on the state for merchandise. The expenses of such traders were minimal, because they did not have to maintain permanent stores or large numbers of employees, and they were in the lowest tax brackets for private traders. Further, mobile vendors could avoid the attention of state tax officials, the police, and other inspectors more easily than could the proprietors of larger, permanent enterprises. These advantages became virtual necessities for Nepmen during the last years of NEP, when merchandise grew scarcer and the state stepped up its campaign to eliminate private trade.

Throughout NEP, then, the majority of private traders belonged to the first two ranks, whose members were most often found in market squares and along sidewalks. All towns of any consequence had at least one market (rynok ), and cities such as Moscow, Leningrad, and Kiev contained many.[34] The most famous was the sprawling Sukharevka in Moscow, through which it was not unusual for 50,000 people to pass on a holiday.[35] An émigré's description of the Sukharevka resembles the portraits sketched by other observers.

Everywhere you look is an agitated, noisy human crowd, buying and selling. The various types of trade are grouped together. Here currencies are bought and sold, there the food products; further along, textiles, tobacco, cafés and restaurants, booksellers, dishes, finished dresses, all sorts of old junk, and so on.

. . . [The merchants cry out to people walking by] "I have pants in your size. Come and take a look!" "Citizen, what are you looking to buy?" "Hats here, the best in the whole Sukharevka!"

Urchins scurry all about with kvass—huge bottles of red, yellow, or green liquid in which float a few slices of lemon. One million rubles a glass [reflecting the severe inflation at the beginning of NEP]. Everyone drinks this poison from the same glass. . . .

. . . In the flea market [tolkuchka ], where secondhand things are sold, there are no stalls or booths. The trade is just hand to hand. Among these vendors are remnants of the old intelligentsia, selling whatever they have left, from torn galoshes to china, but mainly old clothes.

Solitary policemen stroll through the crowds. It is not clear what order they are to maintain, what laws they are to enforce. The market has its own

customs, its own understanding of honor and honesty. A row of booths sells gramophones and records. As is well known, in the countryside gramophones are valued more highly than pianos, and here in the Sukharevka interest in "musical preserves" is great. Recordings [of famous singers] compete with those of speeches by Lenin and Trotsky.[36]

This scene, including the traditional grouping of traders according to their merchandise, was typical of urban marketplaces during NEP. As one journeyed east, particularly in the direction of the Central Asian republics, markets assumed features of the centuries-old local bazaars. In Astrakhan', a traveler reported:

We came to a marketplace where the people milled like flies, to the dirty banks of a stagnant canal where the vendors lived in unpainted wooden boats, sleeping over their "live cars" of sudac [pike perch] and swimming sturgeon. There they pulled out flapping fish to sell us. . . . We were offered milk boiled in gourd-shaped earthen urns, hacks of meat from a carcass being skinned, tubs of salted herring, buckets of still-swimming yellow perch, slabs of pink salmon. Chinamen, six feet high, with faces like yellow idols, walked about hung with ladies' garters, second-hand corsets, pencils, knives. . . . A barber shaved men's heads among the tubs of salted fish. . . . [There were also] bales of strange herbs and dyes [and] mounds of many-colored fruits.[37]

Some of the vendors in market squares were not registered in even the lowest ranks of trade. Peasants, for example, generally did not have to buy licenses in order to bring their produce to market in the towns. Nor were most of the smallest-scale traders—people wandering about selling a handful of secondhand wares—required to purchase a license in a trade rank. Doubtless, too, many itinerant traders did not bother to obtain a required license, particularly if they planned to sell their merchandise in a day or two and move on. The majority of the more settled, "professional" private traders in markets operated out of booths, stalls, or tents, which obligated most of them to purchase rank II licenses. The largest markets, such as the Sukharevka and Tsentral'nyi in Moscow and the Galitskii and Petrovskii in Kiev, contained over a thousand merchants plying their trades from "fixed" (ustoichivyi ) facilities (such as booths). Many other markets in the large cities could boast stalls, covered tables, and the like, numbering in the hundreds.[38]

The number of traders in any given market fluctuated sharply in accordance with the season, the availability of goods, and the level of taxation (particularly the rent charged for a trading spot). In April 1923, for example, the rents and other fees paid by traders in the Sukharevka were raised significantly. As a result, the number of occupied booths

plunged from 3,000 to 1,800. In August this financial burden was reduced, and the ranks of traders began to grow once again.[39] Most traders sold food or textiles, and the availability of these products thus had a powerful impact on a market's vitality.[40] The number of produce vendors varied cyclically, peaking each year in the summer and early fall (unless tax and rent increases negated this pattern). Textile traders depended less on nature and more on the state for their merchandise. If the party line of the day or the economic difficulties of the state reduced the flow of goods to the private sector, textile trade suffered greatly. Textile traders in the Sukharevka, for instance, told a Soviet newspaper reporter that they had arranged to receive goods from a state enterprise in return for keeping retail prices under certain ceilings. But, lamented the traders, the enterprise had been able to supply only a minuscule fraction of the textiles they had ordered. Similar complaints resounded in other markets.[41]

The rural equivalent of the urban markets were the village bazaars and local fairs. Nearly every village had a primary market day each week, usually Saturday or Sunday, during which the local population did much of its shopping. These bazaars resembled their urban counter-parts, though on a smaller scale. Virtually none of the vendors was a full-time trader in a permanent booth or stall, since the bazaars generally functioned only once (sometimes twice) a week. Instead, nearly all the merchants were peasants, local artisans, and itinerant traders traveling from one bazaar or fair to the next.[42] Most of these people were not required to purchase trade licenses or pay the other parts of the business tax, provisions that the state in any case could not enforce effectively in the seemingly boundless countryside. Though few statistics are available concerning village bazaars, their nature is evident in descriptions left by a number of observers, including a worker in the Quaker famine relief program.

The roads leading to a good market are always alive with traffic during the night before market day. All manner of livestock, fruits, vegetables, home-made furniture, ox yokes, boots, and so on, to an infinite variety, have been gathered in the square by daylight. All kinds of traders are to be found, from the peasant woman squatting by her bottle of milk or pile of gay carrots, to the swarthy Armenian cloth merchant surrounded by the oriental splendors of fluttering cotton prints that decorate his booth. Among the crowds move scores of itinerant traders with all their wares worn on the sleeve, so to speak. A pair of boots, three or four petticoats, or a half dozen shirts may comprise the entire stock. The vendor of heterogeneous junk, too, is always present with his pile of monstrous rusty locks, an unmated candlestick or so, hinges, door knobs, and a veritable Walt Whitman catalogue of other miscellany.[43]

An American living in the Soviet Union during the last years of NEP recorded the following scenes at a rural bazaar:

In unending line peasant carts jogged by our window. From the porch of the house we could see three roads, each marked by peasants bound towards the bazaar. . . .

Following an old custom, the sellers had divided themselves off according to what they were selling. In various corners were calves and colts; wheels, wagon yokes, and harness, all home made; cheese, butter, poultry and freshly slaughtered veal. Peddlers with wood carvings, with bark sandals, roamed about; small boys played games, and idle men crowded the vodka store.[44]

Local fairs took place once or twice a year, generally during holidays, and were usually little more than glorified bazaars with much the same types of trade described above.[45] They had been a common means of trade before the Revolution, especially in the countryside. One study reports 14,432 rural fairs and 2,172 urban fairs in 1894. After nearly vanishing during War Communism, they sprouted up again following the introduction of NEP, particularly in localities where they had existed under the old regime. In Moscow guberniia alone, 121 fairs were recorded during 1923, and approximately 440 were reported in the Ural region in 1924. Sometimes, local officials took the lead in organizing these events, but often the fairs reappeared on their own and were registered after the fact. As one Soviet reporter put it, "where they are needed, they appear."[46]

Although rural markets and fairs clearly attracted large numbers of small-scale peddlers and peasant entrepreneurs (a substantial majority of the population still lived in rural areas), approximately 70 percent of all licensed private traders did their business in cities and towns during the first four years of NEP. There were much higher concentrations of consumers in urban areas, of course, and the townspeople were more dependent on merchants for the necessities of life (particularly food) than were the peasants. For every inhabitant of a city or town in 1924/25, urban Nepmen made sales totaling 125 rubles, whereas rural Nepmen sold only four and one-half rubles' worth of goods for every person living in the countryside. The sources of these statistics rarely define the term city (gorod) , and there is certainly room for debate over what should be included in this category. Nevertheless, any reasonable definition of the term would not alter the generalization that most licensed private traders operated in the towns, with Moscow and Leningrad having much the largest numbers.[47] Furthermore, the larger the shop, that is, the higher its trade rank (see table 3), the more likely it was to be found in an urban area.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

In addition, rural private firms of rank V had an average of only 14 percent as much capital as the average urban private enterprise in rank V in 1925. The average rural private trader in ranks III and IV had slightly over half the capital of the average urban firm in each of these ranks.[48] Consequently, the urban percentage of total licensed private sales volume was very high (roughly 80 to 90 percent),[49] since most Nepmen, including virtually all the largest private firms, were in cities.[50]

Most of the data on the Nepmen pertains to European Russia as a whole (roughly the area west of the Urals and north of the Caucasus) or to individual cities. Some information is available, though, for Transcaucasia, portions of Central Asia, and individual regions of European Russia that permits a rough comparison of the Nepmen's strength in each area. In 1926/27, for example, 62.7 percent of all reported private sales were made in the huge Russian Republic (RSFSR), which was divided into many smaller regions. Of these regions, the most important were the central-industrial (which included Moscow) with 23 percent of all reported private sales in the USSR, Leningrad and the surrounding area with 6.8 percent, the Northern Caucasus with 6.6 percent, the middle Volga region with 5.2 percent, the central black earth region with 4.2 percent, the lower Volga region with 3.5 percent, the Ural region with 2.5 percent, and Siberia with 2.1 percent. After the RSFSR, the Ukrainian Republic accounted for by far the most private trade—22.3 percent of the country's total—followed by 6.2 percent for Transcaucasia, 5.6 percent for the Uzbek Republic, 2.3 percent for the Belo-

russian Republic, and 0.9 percent for the Turkmen Republic.[51] Nearly half of all private trade, then, took place in the central-industrial region and the Ukraine.

Although comparatively few private traders were located in Transcaucasia and Central Asia, they controlled trade in their regions to a greater extent than did Nepmen in European Russia. These border regions did not come under firm Bolshevik control until the 1920s and, for the government, were difficult locations in which to set up and supply enough state stores and cooperatives to satisfy the needs of the local populations. In the first half of 1925/26, for example, the Nepmen's share of all trading operations was 97 percent in the Uzbek Republic, 97 percent in Transcaucasia, and 93 percent in the Turkmen Republic, but "only" 80 percent in the Belorussian Republic, 81 percent in the Ukraine, 76 percent in the RSFSR, and 79 percent for the Soviet Union as a whole. Data for other years support these figures by revealing that the private share of total retail sales was higher in Transcaucasia and the Central Asian republics than in the republics of European Russia.[52] Just as Georgia is a hotbed of illegal economic activity today, a higher percentage of private trade during NEP may well have escaped the attention of state officials in the distant Transcaucasian and Central Asian border regions than in the heart of the state. If this was the case, the Nepmen in these areas were all the more dominant than were Nepmen in European Russia.

Certain regions, most notably Belorussia and the Ukraine—the old Jewish Pale—were distinguished by a relatively large number of Jewish entrepreneurs. Approximately 60 percent of the Soviet Jewish population lived in the Ukraine and 17 percent in much smaller Belorussia. Thus, even though only 1.8 percent of the Soviet Union's people were Jewish, Jews represented 5.4 and 8.2 percent of the Ukrainian and Belorussian populations, respectively, in 1927.[53] Many of these Jews (and others elsewhere in Russia) had traditionally been traders and artisans. According to the census of 1897, 31 percent of all "economically active" Jews were shopkeepers, hawkers, peddlers, and the like, and 36 percent worked in "industry," mainly handicrafts.[54] A good number of the latter undoubtedly engaged in trade as well. Following the introduction of NEP, many Jews returned to these activities or emerged from the black market to practice them openly. The resumption by many Jews of their former occupations helps account for the fact that in 1927 nearly two thirds of the private traders in Belorussia and over half in the Ukraine had prerevolutionary trading experience, whereas the corresponding

figure for the RSFSR (where Jews were not as numerous) was only 38 percent.[55]

If the various peoples of the Ukraine are considered individually, we find that 15 percent of the Jews, 3 percent of the Great Russians, and 1 percent of the Ukrainians were traders in 1926. In the case of "workers" (most of whom, particularly among the Jews, were handicraftsmen and thus frequently traders as well), the figures were 40, 20, and 4 percent, respectively. On the other hand, 91 percent of the Ukrainians, 52 percent of the Great Russians, and only 9 percent of the Jews in the Ukraine were peasants.[56] The concentration of Ukrainian Jews in private business is further evidenced by the fact that Jews accounted for 45 percent of all disfranchised people[57] in the Ukraine while constituting only 5.4 percent of the region's population.[58]

An unfortunate consequence of the comparatively heavy concentration of Jews in private trade was the impulse this imparted to anti-Semitism in the 1920s. A number of observers echoed the words of Maurice Hindus on this score.

Jews of this group, the successful Jewish Nepmen, have intensified anti-Semitism in Russia. They are conspicuous in all large cities. They are among the most successful of private traders, which does not escape the attention of the Russian proletariat or of the less fortunate Russian nepman. Both point to the Jewish nepman as the real gainer by the Revolution, the man who is turning the nation's agony into personal profit and pleasure.[59]

As historians of more recent decades have indicated, these views did not die along with NEP.

In many areas a NEP-man had become synonymous with a Jew and he was so treated in some of the belles lettres of the period. When he later [after NEP] served mainly as an employee in a state wholesale establishment or a retail store during the prevailing periods of scarcity, he was accused by the resentful consumers of diverting the scarce merchandise for his own or his friends' benefit.[60]

There was a temporary decline in private trade from the winter of 1923-24 to the spring of 1925. The downturn may even be said to have begun a few months earlier as the "scissors crisis" took its toll on both private and "socialist" trade. At this time, the prices of manufactured goods climbed out of the reach of many consumers, and peasants were discouraged from producing food for the market.[61] But it was not until 1924 that the Nepmen came under the heaviest fire, in the form of tax increases and reductions of supplies and credit from the state.

The effects of these measures were not long in appearing. During this period the number of licensed private traders dropped by approximately 100,000.[62] In Moscow alone, following a sharp tax increase in the spring of 1924, 6,310 of the remaining 16,500 licensed private traders went out of business.[63] This trend is also evident in figures (table 4) available for the Central Market, one of Moscow's largest. As Nepmen were forced out of business during 1924, the volume of private retail sales fell to a level 20 percent below that of 1922/23.[64] Private trade reached its low water mark (that is, until the end of NEP) during the winter of 1924-25. After a drop of over 20 percent in the second half of 1923/24, sales declined an additional 14 percent in the first half of 1924/25.[65] The number of private trade licenses dipped 5 to 6 percent.[66] According to one report, Moscow's host of private merchants shrank fully 39 percent in this period.[67] Since larger enterprises were generally much more vulnerable to the measures adopted by the state than were street hawkers, the sharpest declines (in percentage terms) occurred in the higher trade ranks. In fact, the number of rank I vendors actually increased slightly in the first half of 1924/25.[68]

During 1925, the erosion of private trade was arrested as Bukharin and his allies gained the upper hand in the party. Spurred by the relaxation of state tax, credit, and supply policies (the "new trade practice"), the number of private merchants and their volume of sales rebounded briskly. There were steady increases in the number of private trade licenses from 1924/25 to 1925/26, reversing the earlier decline:[69]

|

Moreover, the percentage of all trade licenses (state, cooperative, and private) that were private in the RSFSR rose in every rank from 1924/25 to 1925/26 (see table 5). Private retail trade, after declining from 1,930 million rubles (1913 rubles) in 1922/23 to 1,574 million rubles in 1923/24 to 1,550 million rubles in 1924, rose to 1,825 million rubles in 1925 and then to 2,240 million rubles in 1926.[70]

Impressive as this recovery was, it proved to be fleeting. The private sector environment became less hospitable during 1927 and then turned openly hostile in the years from 1928 to 1930. The results of the measures taken by the state, first to restrict and then to "liquidate" the Nep-

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

men, are not difficult to detect. In the following gubernii , for example, the number of licensed private traders declined by the indicated percentages in 1926/27 compared to the second half of 1925/26:[71]

|

Reported private retail sales fell dramatically after peaking at approximately 5.2 billion rubles in 1926 and dipping slightly to 4.96 billion rubles in 1927. In 1928, sales were off 27 percent, and during the next two years there were consecutive drops of 33 and 54 percent.[72] The

number of licensed private traders (excluding rank I) declined in similar fashion over the years from 1925 to 1929:[73]

|

Reports from various cities underscore these trends. In Kiev, the number of private wholesale and retail firms fell 40 percent during 1927/28, and sales plunged 47 percent. Of the 3,694 licensed private businesses in 17 Moscow markets (rynki ) in October 1927, only 1,571 remained a year later. Private sales as a whole in the capital plummeted 62 percent in 1928/29.[74] Such drastic changes were noted by many observers. A longtime resident of Moscow wrote at this time that private food traders "have been steadily decreasing both in number and quality and it is very difficult to find them now, though there are still a few small ones in back streets and in the very few areas in Moscow that are not well supplied with shops."[75] According to an American journalist:

As a matter of common convenience, we met in private cafes and ice-cream parlors. We ate in private restaurants, of which there were a dozen along Tverskaya [Moscow's main boulevard, later renamed Gorky Street]. We shopped in private stores, called in private physicians and used the services of private photographers, dentists, and other professional people. Everyone else, from commissars down, did likewise. By the end of the year [1928] most of this private traffic was ended.[76]

One striking feature of the elimination of private traders was that this took place more swiftly than the central state planning agency (Gosplan) had anticipated and far exceeded the pace at which the "socialist" (state and cooperative) distribution system was growing.[77] A report prepared for the Commissariat of Trade had noted this problem as early as 1927.[78] The situation only worsened as Stalin and his supporters gained the upper hand in the party and pressed their attack on the private sector.

The rapid "liquidation" of the Nepmen, before they could be fully replaced by state and cooperative stores, had a powerful impact on consumers because the private share of retail trade had been so substantial. To appreciate the Nepmen's importance, recall that during the first six years of NEP over 95 percent of all rank I and rank II traders were private, and even a majority of the permanent shops in rank III belonged to Nepmen. In fact, over 80 percent of rank III enterprises were privately

owned in 1922, and this figure had fallen only to about 60 percent by 1926. Even in ranks IV and V the Nepmen's share of enterprises was far from negligible—70 percent for rank IV and 50 percent for rank V in 1922, down to roughly 30 and 20 percent, respectively, by 1926.[79]

Thus there can be no doubt that during the first years of NEP, the vast majority of consumer goods reached the public through private traders. Few statistics are available for 1921, because state agencies were not yet able to gather such data for the country as a whole. But the Nepmen's percentage of retail trade must have been extremely large, because the "socialist" distribution system was a shambles after the Revolution and civil war. In any event, even as late as 1926, private entrepreneurs accounted for 40 percent of retail trade (more if illegal and unlicensed sales are included), as shown below in the sequence of private shares of retail sales.[80]

|

Given this prominence of the private sector in the first two thirds of NEP, the headlong elimination of the Nepmen after 1927 could not help producing fallout across the land. In 1929 Narkomfin's journal declared with considerable understatement (referring to the Ukraine): "There are hardly sufficient grounds to assume that the decline of private retail sales has been covered completely by an increase in sales in the cooperative sector." In 1926/27, the article explained, there were 110 people in Kiev for every retail business, 126 people per business in Khar'kov, 106 in Odessa, and 110 in Dnepropetrovsk. But by 1928/29, the number of people per shop in these cities had risen to "a minimum of 150 to 160."[81] It was not unusual by 1928 to see such newspaper headlines as "Private entrepreneur eliminated but not replaced."[82]Torgovo-promyshlennaia gazeta 's correspondents filed reports from around the country on the appearance of "trade deserts" (torgovye pustyni ), which, as the name suggests, were regions in the countryside where no "socialist" shops appeared to fill the void created when the local Nepmen were driven out of business. In such cases, peasants often had to travel several (sometimes even thirty to forty) kilometers to purchase essential products. Even if a village had a cooperative store or two, they were frequently empty of desirable goods. When a shipment of merchandise arrived, the useful

items were snatched up in a day or two by customers who had often been standing in line for many hours.[83]

These problems were most acute in the countryside, but the rapid "liquidation" of private traders in Moscow prompted at least one Soviet reporter to apply the expression "trade desert" to the capital itself. A colleague in Smolensk wrote that the elimination of private traders there was proving to be something less than an unmitigated blessing for consumers. "Indeed," he explained, "it is unbelievable, but true, that at present not a single commodity may be purchased in the city without waiting in line. Every day the population wastes many thousands of working hours standing in lines."[84] Such reports would not have provoked an argument from Eugene Lyons, who made the following observation.

That first winter [early 1928] was an exceptionally bitter one, even by Moscow weather standards. Waiting on queues for bread and other necessities was that much more agonizing. Everywhere these ragged lines, chiefly of women, stretched from shop doors, under clouds of visible breath; patient, bovine, scarcely grumbling. Private trade channels were being rapidly shut off, before the government was able to replace them with official channels.[85]

As pressure mounted on the Nepmen from 1926/27 through the rest of the decade, private trade not only declined but changed in character as well. Virtually all operations able to survive the onslaught of the state were very small scale. The larger enterprises in permanent facilities were most visible, most obviously "capitalist," and thus the first to be eliminated. In 1925/26, for example, 17 percent of all private sales reported to the state were wholesale, whereas four years later virtually all licensed private wholesalers had been driven out of business. This is hardly surprising, for it was next to impossible for large private retail and wholesale operations to escape the attention of state officials, especially wholesale enterprises dependent on the state for much of their merchandise. Taxes and fees levied on large firms were higher than those imposed on petty traders, and Nepmen in the upper ranks could not pick up their businesses and elude a policeman or tax inspector the way rank I and some rank II traders could.[86] An American living in Moscow at the end of the decade wrote that "there are almost no privately owned stores in the city; any who wish to continue the unpopular profession of merchant for their own profit must trade from these rickety stands in the market places or at street corners."[87] The state Central Statistical Bureau reported that by January 1, 1930, nearly two thirds (64 per-

cent) of the 123,000 registered private traders were peddlers and street hawkers (raznoschiki ) and that 19 percent operated from tents, booths, or stalls. Only 17 percent still conducted their business from even the most modest shops (lavki ) or stores (magaziny ).[88]

A demand that far exceeded the supply of most consumer products, combined with the declining number of private traders, spawned a revival of bagging. The shortages of both food and manufactured items, labeled the "goods famine" (tovarnyi golod ) by the press, produced streams of people traveling in opposite directions—some trekking to the countryside in search of food and others coming to the towns to trade for manufactured goods.[89] This type of "amateur" trade continued after NEP. As famine began to stalk the Ukraine in 1932, for example, a Russian who had emigrated in 1914 and then returned to the Soviet Union found on a trip to Odessa "that the train guards, conductors, and attendants were all speculators. They were buying food in Moscow, always better provided for than other cities, and selling it at fantastic prices down in the stricken southern land."[90] Although bagging seems not to have been as widespread at the end of NEP as it had been during War Communism and 1921/22, its resurgence in 1928/29 indicated the inadequacy of the "socialist" consumer goods production and distribution system when the Nepmen were driven out of business.

Another consequence of the state crackdown on the Nepmen was that a greater percentage of private trade was conducted illegally, without licenses. As taxes and harassment from local officials became more onerous, an important survival skill for many private traders was the ability to avoid detection. This generally meant operating underground in the black market or selling goods without a license in the streets and running whenever the police approached. As one woman was buying peaches from a private trader in the summer of 1928, "the pedlar and his enormous tray suddenly disappeared as completely as the vanishing gentleman of a conjuror's trick. A warning of the approach of a policeman had passed down the line [of hawkers] and the line dissolved. The vendors are required to have licenses; this one was among the hundreds who had none." Another foreign resident reported that "the government attempted to restrict this peddling by means of taxation, but the pedlars always tried to evade these taxes. A frequent sight in Moscow in 1929 was to see a whole mob of petty dealers running before a policeman or two, carrying baskets on their heads or arms, pushing wheelbarrows, as they attempted to save themselves from the wrath of the law."[91] The wife of an American mining consultant in the Soviet Union, noting that most markets were closed by the state in 1929/30 with the onset of

mass collectivization, indicated that it was still possible to purchase food surreptitiously from resourceful peasants.[92]

Thus private trade came full circle by the end of NEP. As the state stoked up its campaign to "liquidate the Nepmen," adopting "administrative measures" of the sort that had distinguished War Communism, private trade returned increasingly to the forms it had assumed in the years immediately following the Revolution. During War Communism this meant almost exclusively small-scale, unsophisticated, illegal (or barely tolerated) sales and barter, sometimes conducted by bagmen. Little changed immediately after the introduction of NEP except that this activity became less risky and attracted more people. But before long, as we have seen, the number of larger, permanent private shops began to increase (at the expense of many of the marginal petty vendors) and peaked in 1925/26 after suffering a brief downturn in 1924. In 1926, then, the Nepmen were as far from the atmosphere of War Communism as they would get, and thereafter their path turned, slowly at first, back in the direction of an environment bracing for Bolsheviks but bleak for private merchants. The state policies at the end of the decade eliminated virtually all private traders except the very small scale and the surreptitious—the same sort characteristic of the era of War Communism.

Although it is beyond the scope of this work to cover private entrepreneurs in the 1930s, a few words should be added as an epilogue concerning legal private trade immediately after NEP. The state grain-collection and collectivization drives at the end of the 1920s were accompanied by an intense campaign against the Nepmen. But just as the collectivization offensive was halted (temporarily) in the spring of 1930, so too was the effort to eliminate private trade. Though the permanent stores of private traders remained closed, small-scale trade was again permitted in markets and bazaars, primarily because the state was unable to supply adequate amounts of food to the urban population. The bulk of this trade, which continued throughout the decade, was conducted by collective farmers, artisans, and people selling odds and ends, as described by Julian Huxley in the summer of 1931:

Dingy rows of stalls, with narrow passages between; beyond, men and women squatting in front of the produce they had brought—here eggs, there vegetables, here again potatoes; a few carts belonging to kulaks, laden with vegetables; a row of cobblers; a few sellers of mushrooms and flowers. . . .

A big-built factory worker was holding out about a pound of raw meat,

half unwrapped from its covering of old newspaper; a neatly-dressed woman, probably a typist in some office, had three eggs, which she proffered in her open hand-bag; an old man was trying to sell two small dried fish; another woman had half a pound of butter. There were city workers who, having bought their supplies at the Cooperatives on their ration cards, were now trying to get money for some luxury by selling them in the open market, where they could get four or five times as much as what they paid for them.[93]

An American engineer, who worked in the city of Groznyi in 1931-32, wrote:

There is still some private trade in Russia, and lately the Government has allowed it to increase. It includes the outdoor markets and some small handicraft shops for shoe repairing, tailoring, blacksmithing, barbering, dressmaking, and the like. . . .

In addition to the small and insignificant booths on the main street belonging to private traders there also existed a huge outdoor market to which the peasants brought their goods for private sale. These markets or bazaars, as the Russians call them, are found in every center and are a necessary source of food supply for the people because the cooperatives cannot yet supply the needs.[94]

Other forms of legal private enterprise led a precarious existence in the cracks of the new planned economy. Private horse-drawn cabs, for example, were tolerated for a time, because not enough cars were produced to fill the need for taxis. At the end of 1935, a new line of trade was approved. In December the party unexpectedly removed the taboo on Christmas trees that had been in force since the end of NEP, announcing that one might celebrate the New Year with a New Year's tree. "The very next morning the markets were full of trees. All night long, axes had been busy in the suburban forests of Moscow and at dawn the roads leading to Moscow saw a procession of peasant carts laden with trees." But ornaments were difficult to find on such short notice after several years without Christmas trees. As a result, old women appeared on street corners selling "old-fashioned Christmas toys, hidden for years, mostly little angels. They did good business."[95]

Chapter 5

Supplying the Nepmen

It is the NEP-man who hurries here and there, and by devices which are always suspect, obtains exceptionally interesting goods, which somehow the Cooperatives do not always manage to offer. But why that is I could not find out.

—Theodore Dreiser

It is difficult to find a more convenient field of operations for all sorts of pretenders than our expansive country, filled either with exceedingly suspicious or exceedingly gullible administrators, managers, and social workers.

—Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov

Throughout NEP the main obstacle facing traders (state, cooperative, and private) was obtaining goods, not selling them, since demand for many products far outstripped supply. Soon after launching his first business ventures in Russia, Armand Hammer discovered that the shortage of most commodities was so great "that any article of general use or consumption produced inside the country at anything like a reasonable price is generally sold beforehand."[1] One advantage held by the Nepmen over the state and cooperative retail network was their ability to acquire merchandise more efficiently and resourcefully (and sometimes more deviously). Goods flowed into private traders' hands from a number of suppliers, whose relative significance varied with the nature of a Nepman's business and with changes in the economic and political climate.

One of the most important sources was the "socialist" sector itself. During the course of 1921 and 1922 most state factories were ordered to operate on a cost-accounting (khozraschet ) basis, meaning that they could no longer rely on the state to provide them with raw materials, pay their workers, and absorb their finished products regardless of how inefficiently they operated. Instead, with the umbilical cord cut, state enterprises found themselves on their own in the marketplace, frequently in desperate need of funds for raw materials, wages, equipment, and so on. Many state operations in such straits sold off nonessential goods and equipment at low prices in order to obtain working capital. This phe-

nomenon was known as razbazarivanie (literally, "scattering through the bazaars"), which is usually rendered as "squandering." Very often, the only customers with ready cash were Nepmen. As a Soviet writer remarked in 1924, state firms that "plunged into the anarchy of the market became the source of extremely intensive primary accumulation for the new trading bourgeoisie."[2]

It is, of course, impossible to ascertain the total value of goods involved, but many observers were convinced that a large amount of state property fell into private hands through this process. The state publishing house Krasnaia Zvezda, founded in 1923 to publish military literature, sold cartloads of its paper and expensive stationery to Nepmen at low prices. Somehow, the publishing house also had musical instruments, first-aid kits, and bicycles, which, not surprisingly, it was anxious to sell to anyone available. During the famine in the Volga region at the beginning of NEP, a state livestock breeding agency sold to Nepmen a large portion of its resources (scythes, sugar, salt, oats, and hay). Even some of the agency's purebred stock was sold or rented to private persons for use in horse races. Up to 1927 state enterprises and agencies had sold 1,661 cars and trucks (and 4,000 motorcycles) worth several thousand rubles apiece to private buyers for only 400 to 500 rubles each.[3] As in the case of Krasnaia Zvezda, it was not unusual for a state operation to sell commodities that had nothing to do with its official activity. Agencies as unlikely as Glavchai and Khleboprodukt (which handled tea and grain, respectively) raised cash by unloading large quantities of textiles on the free market in 1921/22. Even Gosbank acquired a variety of goods at the beginning of NEP, some of which it sold to private entrepreneurs.[4]

Not all state sales to Nepmen were haphazard or unsound. Private traders as a rule were more efficient than the state and cooperative retail system, and they could also charge higher prices than their "socialist" competitors (since the latter were supposed to observe price ceilings). Consequently the Nepmen were often able to absorb higher prices and harsher credit terms from state suppliers than could "socialist" enterprises in need of the same goods. As a result, many officials in state factories and trusts, forced to fend for themselves on khozraschet , found it possible to overcome any ideological scruples they may have had concerning sales to the "new bourgeoisie." Though this provoked a complaint from Tsentrosoiuz (the central agency of the cooperative system) that "large amounts of goods proceeded from trusts, not to cooperatives, but to the private market [in 1921/22]," such protests were to no

"Nepmen," a watercolor painted in the 1920s by Dmitrii Kardovskii.

(Serdtsem slushaia revoliutsiiu . . . [Leningrad, 1980], picture no. 118)

The Sukharevka, Moscow's largest outdoor market. The name of the market was sometimes used

as shorthand for private trading in general. ( Illiustrirovannaia Rossiia , no. 50, 1926, p. 1)

Young street traders in Moscow in 1921. Primitive trade of this sort was most widespread at the

beginning and end of NEP. (F. A. Mackenzie, Russia Before Dawn [London, 1923], page facing p. 82)

Furniture and other personal possessions for sale in one of Moscow's outdoor

markets at the end of NEP. (Illiustrirovannaia Rossiia , no. 23, 1930, p. 6)

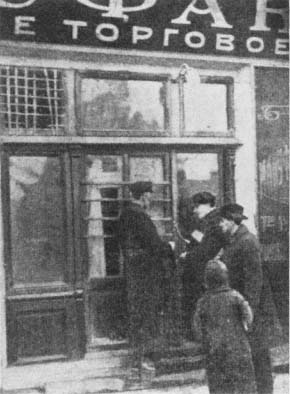

A group of street traders outside a state shoe store. ( Illiustrirovannaia Rossiia , no. 10, 1927, p. 1)

A row of clay-pot vendors in a rural market. The dominance of private traders was generally

most pronounced in rural localities. (Illustrirovannaia Rossiia , no. 27, 1929, p. 5)

A baranka (ring-shaped roll) vendor plying his trade during a

village market day. (Illiustrirovannaia Rossiia , no. 30, 1926, p. 1)

A state tax inspector and policeman sealing a shop whose proprietor had

fallen behind in his tax payments. This scene became a common sight during

the last years of the 1920s. (Illiustrirovannaia Rossiia , no. 13, 1925, p. 5)

A Soviet poster depicting a Nepman uttering a prayer: "O Lord, help me,

a sinner! Help me to cheat and circumvent this [Soviet] power that I hate."

(Negley Farson, Black Bread and Red Coffins [New York, 1930], page facing p. 208)

A portion of a May Day parade in Leningrad. The sign below the grimacing mask reads:

"I buy from a private trader." Below the smiling mask are the words: "I shop in a cooperative."

(Sovetskoe dekorativnoe iskusstvo. Materialy i dokumenty 1917-1932. Agitationno-massovoe

iskusstvo. Oformlenie prazdnestv. Tablitsy [Moscow, 1984], picture no. 225)

A clerk in a cooperative store (first frame) admonishes a woman:

"Wait a minute, Citizen. Notice that there are many of you, and I am alone.

Can't you see that I am busy?" This rudeness sends the woman hurrying (second frame)

to a private trader, who greets her much more solicitously. It is interesting to compare

the point of this cartoon (published in Pravda , January 4, 1928) with the point

of the masks in the Leningrad May Day parade (photo on preceding page).

avail. Indeed, a decree of April 10, 1923, permitted state trusts to give their business to Nepmen even when state and cooperative customers were available, as long as the Nepmen offered more favorable terms. Transactions of this sort were particularly common in the first years of NEP, when the state and cooperative retail network was extremely inefficient. But even in 1926, the state salt syndicate announced that it would be desirable to sell to Nepman 30 percent of the syndicate's output, precisely because private traders could accept less credit and higher prices from the syndicate than could the cooperatives.[5]

That there were comparatively few state and cooperative stores, particularly in the first half of NEP, was another compelling reason for state firms to sell to Nepmen. Otherwise, goods simply would not reach a large portion of the market. For every 10,000 inhabitants of the countryside in 1924/25 there were 6 cooperative shops, 1 state store, and 31 licensed private trading operations. The actual number of private traders was certainly much higher, for it was quite easy to trade on a small scale without a license, particularly in the countryside. As we have seen, private entrepreneurs also dominated trade in the cities during the first years of NEP, handling over 80 percent of urban retail trade in the estimate of the state Central Statistical Bureau. The effectiveness of the private retail network was clear to state officials in the trusts, syndicates, and factories. In the middle of NEP, for example, the state sugar trust maintained that it was essential to market 26 to 28 percent of its products through Nepmen because of the weakness of state and cooperative trade in the countryside. According to the division of the All-Russian Textile Syndicate (VTS) headquartered in Rostov-on-the-Don, private traders were practically the only people available early in NEP through whom textiles could reach consumers. On a related point, an article in one of the Council of Labor and Defense publications noted that during the "scissors crisis" in the fall of 1923, many cooperatives, "artificially supported" by the state, collapsed. Had there been no private traders to market textiles produced by state industry, factories would have been glutted with finished wares, and "it is difficult to imagine the sort of catastrophe for VTS that would have accompanied the autumn crisis."[6] Viewed in this light, sales to Nepmen were in line with Lenin's dictum of "building communism with bourgeois hands."

In 1922 the state system of industrial trusts and syndicates sold roughly 50 percent of its goods directly to private traders. The figure proceeded to fall to 35 percent by 1922/23; 15 percent in 1923/24; 10 percent in 1924/25; and about 8 percent in 1925/26.[7] The declining per-

| |||||||||||||||||||||

centages should not be taken as an indication that the state continually reduced sales to Nepmen during this period. Since the total output of state industry increased markedly in these years, sales to private traders, though falling in percentage terms, did not decline in absolute value after 1923/24 (see table 6). It seems likely that the volume of such sales to Nepmen was off somewhat in 1923/24 compared to 1922/23, as a result of the crackdown on private trade in 1924. But the paucity of comparable data for 1922/23 hinders quantitative comparisons. In any case, volume rebounded in the following years despite the shrinking percentages for those years.

Private merchants were primarily interested in the output of consumer goods branches of state industry, commodities such as food products (tea, coffee, sugar, and salt), textiles, kerosene, tobacco, matches, and leather and rubber items such as footwear. Information is fragmentary for the beginning of NEP, but it is safe to assume that trusts and syndicates in these branches of production generally made between one quarter and one half of their sales to Nepmen.[8] By the middle of the decade, record keeping had improved sufficiently to permit more detailed estimates (see table 7). Approximately 80 percent of direct private purchases from trusts and syndicates were concentrated in just a half dozen or so branches of production. In 1924, textiles alone (primarily cotton cloth) accounted for over half such sales to private entrepreneurs. But the demand for textiles far exceeded the state supply, and as the number of state and cooperative stores increased, textile trusts and syndicates were instructed to sell more of their goods to "socialist" enterprises.[9] The results were apparent as early as 1925 and were striking by 1926 (see table 8).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In addition to legal, direct purchases from state agencies, private traders could obtain goods from the "socialist" sector by various illegal, semilegal, and indirect means, much the same way large quantities of state property reach private hands today in the Soviet Union. Although little quantitative information on this activity is available, it is clear that a considerable volume of commodities reached private traders through "informal" channels. Few Bolsheviks knew how to trade during the early years of NEP, as Lenin lamented repeatedly, and state enterprises often had to hire people with experience in private trade to help market goods or obtain raw materials. These people were then in a position to divert state supplies into the private sector, because they were often more aware of what materials were on hand than were the nominal managers.[10] It was not unheard of at the beginning of NEP for a private trader to have a second "full-time" job in a state enterprise. In 1922, for instance, the state trading agency Gostorg had a number of employees who simultaneously operated private businesses that were well stocked with Gostorg's wares. Occasionally a private contractor or supplier for a state agency who was also an official in that agency could buy and sell goods to and from himself—on rather unattractive terms for the state, one might suspect. One Nepman even wrote letters proposing transactions to himself in his other capacity as an official in a state firm.[11]

Some of the first private stores opened in 1921 were owned by former state employees who had used their official positions to acquire the goods they then sold on their own. Other people remained in state service, registering their shops under someone else's name (often a close relative), and then supplied the stores with products they controlled as state officials. The search for goods was also joined by relatives scattered about in the "socialist" sector (nevesta v treste, kum v GUM, brat v narkomat; "a fiancée in a trust, a godparent in GUM [Moscow's leading department store], and a brother in a People's Commissariat," as Mayakovskii once quipped). In 1922, for example, an agent of Gostorg at the Nizhnii Novgorod fair delivered supplies at low prices to the private firm Transtorg, whose director happened to be his brother. Nor did the ties between the two enterprises end here. A member of the board of directors of Transtorg was also head of a division of Gostorg, and the founder of Transtorg was at the same time an agent for Gostorg—all quite legally.[12]

In December 1922, on the heels of similar directives and draft decrees prepared by several state agencies, the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom) adopted a law making it illegal to engage in private busi-

ness activity while employed by the state.[13] If Sovnarkom's intent was to dam the "unofficial" flow of state resources into the private sector, the decree was futile for a number of reasons. First of all, the accounting practices in many state enterprises, especially at the beginning of NEP, were sloppy or nonexistent, and it was relatively easy to steal goods from an agency that did not even realize it possessed them. The disappearance of supplies from state and cooperative operations as a result of poor record keeping and other sloppy practices was dubbed the "four u's"—utruska, usushka, utechka , and ugar (roughly, "spillage," "shrinkage," "leakage," and "waste"). Eight years after the Revolution, for example, officials at the Leningrad naval yard had still not made an inventory of the vast amount of goods lying around the facility. Entire warehouses, listed as empty in the naval yard's books, were actually full of valuable commodities at the mercy of thieves and the elements. Millions of rubles' worth of state goods were stolen across the land, and much of this loot found its way into the hands of private traders. To illustrate, a Nepman named Brounshtein, representing a private firm with virtually no capital, contracted to supply a state factory with nine hundred tons of oil in return for some steel pipe. After promising the steel pipe to another enterprise in exchange for some roofing iron, Brounshtein stole the oil he needed from the Leningrad naval yard. He then carried out all of the transactions described above, leaving himself with a supply of roofing iron, which he sold. Part of the proceeds went to certain naval yard employees who had helped him steal the oil. In 1922, American Relief Administration officials in Rostov-on-the-Don learned that bands of thieves were stealing state supplies from railroad freight yards and selling them to private wholesalers. These Nepmen sometimes bribed the station agents to ship their newly acquired goods to various markets by rail. At times the thieves could be brazen. Employees in the state factory Treugol'nik stole cable from the factory and then sold it back to the factory through a private firm, Kontora Martinova, they had set up.[14]

Even Walter Duranty, Moscow correspondent of the New York Times , and Herbert Pulitzer, son of Joseph Pulitzer, were peripherally involved in the theft and resale of state property at the beginning of NEP. As Duranty tells it:

Among our flock of American wage-slaves there was one white crow in the person of Herbert Pulitzer, the principal owner of The New York World , in whose vineyard he then chose to labor as a mere reporter. The knowledge of his wealth must have reached Moscow, for one day a Russian came to his

room at the Savoy, where I was sitting, and circumlocutively invited him to buy a carload of sugar. I think the price was $1,200, and the Russian, who had a note of recommendation from the restaurant in the Arbat where we always took our meals, declared that it could be sold immediately for $5,000. There would be some small commissions, he smiled knowingly, but we could count on a clear profit of at least 200 per cent. I was interested, but the rich Pulitzer asked crudely, "Who owns the sugar now, and where is it?" "Oh," said the Russian airily, "it is Government property stored in freight cars at one of the Moscow depots. But they've forgotten all about it, and of course some of it would go to sweeten the only official who knows anything. I assure you there is not the slightest risk."

During another meeting over a good deal of French champagne, the Nepman coaxed $500 from Pulitzer and $100 from Duranty and raised the rest elsewhere. After completing the transaction, he spent half of his thousand-dollar profit on a lavish banquet (to which Pulitzer and Duranty were invited) and gambled the rest away the same evening. Duranty learned later that in the following months he had made approximately $50,000 in similar business operations and then slipped out of the country to Paris.[15]

Despite warnings and decrees from the state, some Nepmen maintained cozy relationships with state officials (frequently with bribes) in order to obtain merchandise or special services. This system, called by some wags krugovaia poruka (an old Russian term meaning mutual responsibility), was the next best arrangement to being both a Nepman and a state employee oneself.[16] The businessman I. D. Morozov, for instance, had had many connections in the West before the Revolution, and after opening a store in Moscow during NEP, he decided to try to renew some of these old ties in order to obtain Western goods. To this end he enlisted the aid of the chairman of a Soviet trust who was about to go abroad on a business trip—and who had been the director of one of Morozov's factories before the Revolution. The director of the Northern Section of the Association of State Workers Artels (ORA) illegally rented the services of one workers' artel' of five hundred men to a private contractor of ORA, named Kornilov, for four months at the rate of one ruble per head. Kornilov employed these workers in his own business ventures, which had nothing to do with ORA (such as cutting, loading, and unloading firewood).[17]

To be sure, few Nepmen contemplated international maneuvers or rented brigades of state workers. Most of the collusion between state officials and private entrepreneurs bore a greater resemblance to the fol-

lowing cases. In 1921 a man named Alkhazov was arrested for cocaine trafficking and sentenced to a year in prison. Following this setback he managed to install himself as an official in a state trading agency (Dagtorg) and soon began to conduct shady transactions. In Moscow he met an old acquaintance, now a director of a private firm, and they contrived to be of use to each other. On one occasion Alkhazov went to the Nizhnii Novgorod fair and purchased (from another state agency) a large quantity of textiles in Dagtorg's name, even though Dagtorg had instructed its representatives not to buy textiles. According to the sales agreement, the goods were to be sold to the people of Dagestan (in the eastern portion of the Caucasus), but Alkhazov hurried back to Moscow and sold half the textiles to his friend. The rest reached private traders through other channels. To cite another example, in 1922 the OGPU charged the director of a state tobacco-processing factory and two former private wholesalers with creating a "black trust" that sold 90 percent of the factory's output to Nepmen.[18] In some instances, state agencies that officially had nothing to do with the trade of various products obtained them anyway from trusts and syndicates for resale to private wholesalers.[19]

Nevertheless, most private traders were small-scale vendors in markets and bazaars and thus in no position to strike special deals with influential state officials. If such junior Nepmen (and many larger-scale merchants as well) wished to obtain goods directly from the "socialist" sector, they had to tap the state distribution system farther down the line. This would often entail bribing a clerk in a state or cooperative store to withhold goods and sell them to the private trader. On other occasions "socialist" clerks, store managers, and others took the lead in these transactions, knowing that they could sell merchandise to private traders at prices well above the official ceilings. This activity was widespread, prompting the Supreme Council of the National Economy (VSNKh) in July 1924 to send out a directive to the enterprises under it forbidding the practice. But this and numerous other official complaints proved futile, and the sale of goods to Nepmen from state and cooperative wholesale distribution agencies and retail stores continued to flourish.[20]