Dancing Mothers and Kodaira Ethnics

Following the "child" shrines were six blocks of female folkdancers moving forward rhythmically to the alternating strains of the "Kodaira Onda " and the "Greater Tokyo Ondo, " which were broad-cast throughout the day as well.[8]

Kodaira Ondo

Ha-aa. Long ago in Musashino was Ogawa village, you know.

A post station along an avenue of zelkovas. (As for now,)

Now there are seven: Kami-Naka-Shimojuku, Kubo Slope—hey now!

(Throngs of people)

Enjoying a cool moonlit eve in Misono.

(Kodaira is a good, fine place!) You bet!

(Kodaira is.)

Ha-aa. Come now, let's sing; make a circle and dance, you know.

Flower of Koganei, along the canal. (As for fragrance,)

Fragrant are Gakuen, Tsuda College, Arts College, Hitotsubashi.

(Now then), Shinmei-gu.

The Seibu line carries your dreams.

(Kodaira is a good, fine place!) You bet!

(Kodaira is.)

Ha-aa. Come now, let's sing; make a circle and dance, you know.

To the east, Tsukuba; to the west, Mt. Fuji. (And in between,)

(Now then), avenue of buildings.

Strike up the ondo and build up the town.

(Kodaira is a good, fine place!) You bet!

(Kodaira is.)

( ) = chorus

Lyrics: Yokozawa Chiaki

Music: Hayama Taro

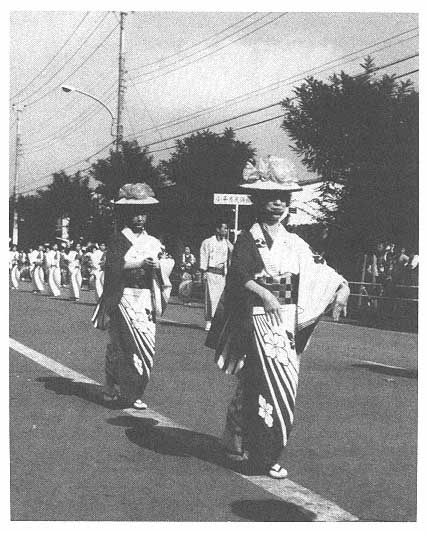

The six groups averaged between 70 and 150 members, mostly women between forty and sixty-five years of age for whom folkdancing was a weekly pastime. I recognized among the dancers several of the clerks at a local supermarket. One of them later told me that her group practiced once a week and also performed at various festivals and functions elsewhere in Tokyo. For over an hour, row after row of dancers clad in decorative kimonos filed by, swaying and stepping in perfect unison. Their expressions were sober, crinkling into brief smiles only at the sight of an acquaintance among the appreciative spectators (fig. 5).

Trailing a slight distance behind these six groups was a seventh, the women of the Niigata prefectural association, dancing the "Sado okesa, " a style of folkdancing that originated in Sado Island. They had not participated in the past several festivals. Whereas the other groups were identified by modest hand-carried signs, the Niigata women announced their presence in a bold way. They were preceded by a sound truck outfitted with several large white panels, bordered with colorful pom-poms, on which was brushed the name of their association in giant red characters.

When each group of dancers reached the end of the parade route, they broke rank. A few fell back to mingle with their friends, who graciously "oohed" and "aahed" over their performance and enviously fingered the dancers' festive kimonos.

It is fitting symbolically that the "child" shrine procession should be followed by one featuring older women. In the first place, females—wives and mothers especially—are regarded by city hall as a "class" of resident and are acknowledged collectively as the nexus between the private household and the public neighborhood or society at large. They are also regarded as mediating between past and present, "tradition" and "modernity." Wives and mothers negotiate these counterposed domains through their husbands and or children. Women's groups, to a certain idealistic degree, function as extensions of the household, as the ancestors' festival dance (obon ) in Kodaira illustrates.

The obon dance, jointly organized by the women's and youth groups

Fig. 5.

Female folkdancers. (Photo by author)

of participating neighborhood associations, is highly valued as an opportunity to instill in youngsters an appreciation for "traditional" entertainment. Rehearsals are held, for sloppy dancing on the two nights of the festival would "exert a bad influence on the impressionable youngsters" (KCH, 1 July 1958). Similarly, groups of mothers are made responsible for collecting and publishing local lore and folktales,

which are considered to be of socially redeeming value for children. In the context of the citizens' festival, the polished female folkdancers collectively are idealized as the civic materfamilias of kodairakko and, as such, symbolize the operations and consequences of the dominant ideology of the "family system."

The "family system"—which refers to the tendency to extol the patriarchal household as the center of state, national, corporate, and social structures (cf. Maruyama 1969, 36)—relies on the social import and utility of the mediational role of wives and mothers. This system does not accord females qua females high status; rather, it is the "female" gender role of mediation that is acknowledged. Not rights and respect but, instead, service to the patriarchal household and, by extension, to the state is the subtext here. Although the "male:public::female:private" equation has been roundly critiqued and dismantled by feminist theorists,[9] it nevertheless informs the dominant representation in Japan of men's and women's social spaces, and so it is in reference to this equation that I explore the sex-gender dynamics of the "family system."

The private/public distinction is usefully regarded as a "culturally constructed continuum which gives rise to different patterns of male power and control" (Brittan and Maynard 1984, 130). "Male power and control" refers to a man's potentially unlimited access to manifold public spheres of interest, as well as to a private household. Contrarily, the housebound married woman is triply circumscribed by the "female" gender roles of "mother," "housewife," and "wife," and their respective activities of childraising; cooking, cleaning, and washing; and sexual services. However complementary the private/female and public/male domains appear or are presumed to be, the actual relationship between the two domains is neither symmetrical nor equal. From a man's perspective, the continuum is continuous, but from a woman's perspective, it is discontinuous. A husband has the opportunity to take on domestic chores, but a wife cannot assume at will her husband's work, although the quality of her wifely role can affect the quality of his work and, by extension, the social standing of the household. The implication is that the work married women do in their homes is invisible and becomes apparent only when it is not completed or is managed improperly. It is only when something goes wrong with the system—increased incidences of school vandalism, drug abuse, juvenile delinquency, and so on—that the mediational role of wives and mothers is acknowledged (Atsumi 1988; Brittan and Maynard 1984, 131; Japan Times, 31 December 1983). Significantly, during his tenure, Mayor Oshima attrib-

uted to women a greater capability than men to negotiate differences, and he asked various women's organizations to help mediate strained relations between natives and newcomers. As I pointed out in chapter 1, the gender ideology informing furusato-zukuri projects supports the practice of gender-role segregation, whereby married women, in the capacity of wives and mothers, are to nurture "old village" consciousness within their families.

Some of the female folkdancers represented another aspect of furusato-zukuri in Kodaira, that of "prefectural ethnicity." The Niigata women danced to their own tune, as it were, at the ninth citizens' festival, a reminder of the residents' diverse backgrounds and the we/they dichotomy at work. Their dance, the "Sado okesa, " may be construed as a symbolic expression of their "ethnic" identity, the boundaries of which are drawn, for the sake of convenience, at the prefectural level. It is an expression that is at once condoned and moderated—condoned in the sense that the citizens' festival was designed as a forum for interpersonal exchange, and moderated in that the ultimate purpose of such commingling is the creation of Furusato Kodaira. The diverse ethnicities of nonnatives are celebrated not for their own sake but as resources to be assimilated and appropriated toward the task of furusato-zukuri. Along with native-newcomer, another dialectical relationship complicating the narrativity of the festival parade is Kodaira-prefecture ethnicity.[10] Thus, the female folkdancers qualified themselves as members of Kodaira's Niigata Prefectural Association.

The several prefectural associations in Kodaira were established in the 1970s by concerned "ethnics" as one expression of the localism accompanying the post—oil shock revaluation of regional folkways. Prefectural associations offer to newcomers what parishes and consociations offer to natives; namely, support and camaraderie. Although members of these associations come from different cities, towns, and villages within a given prefecture, it is from their position as Kodaira residents that the prefecture itself is regarded as a local place in common. Logistically, too, the prefecture is a desirable boundary. Many of the associations are involved in interprefectural trade and tourism, the efficiency of which would be hindered were ethnic boundaries drawn on a smaller scale.

Beginning with the first citizens' festival, stalls stocked with prefectural specialties have been set up in a "corner" devoted to "specialty shops of the prefectural associations."[11] As explained in the city newspaper, "The main theme of this first citizens' festival is: Let's build

ourselves afurusato! Seizing the opportunity to mingle constructively and positively, members of the prefectural associations will perform regional dances and sell regional products" (KSH, 1 October 1976).

As Mayor Oshima declared in a Tokyo shinbun interview at the time, "Our plan is to build a unique furusato enriched by the local color of the prefectural associations." In that same article, the chair of the Fukui prefectural association proudly affirmed his pride in that prefecture and expressed a desire to "introduce the songs of Fukui packhorse drivers to all Kodaira residents." His gang of seven horse riders performed at the second citizens' festival, and he recalled thinking at the time, as the horses pranced up Akashia Road, "What a real furusato -style adventure it would be if the horses bolted!"

These are among the ways in which the affective compass of Furusato Kodaira is stretched to assimilate the different prefectures. The citizens' festival not only is an occasion to "intertwine 150,000 hearts" but also provides an opportunity to redraw affective boundaries—so that Kodaira ethnics can demonstrate their prefectural affinities without slighting their Kodaira identity. Although these affective boundaries transcend the city's administrative borders, the territory encompassed is none other than Furusato Kodaira.

One other ethnic participant in the citizens' festival since 1978 has been Obira, Kodaira's sister-city in Hokkaido. Obira, a town on the northwest coast of Hokkaido, briefly enjoyed the limelight in June 1984, when the hull of the Taito-maru was discovered by salvagers. In 1945 the ship was sunk by an unidentified submarine while en route to Japan from Sakhalin with a cargo of seven hundred expatriates. Radio, television, and English newspaper reports of the discovery consistently referred to "Kodaira," and, indeed, local legend has it that sister-city relations between Kodaira and Obira were initiated because they share the same name characters.

The population of Obira, which became a town in 1978, has been declining steadily at a rate of about 10 percent a year; in April 1984, it totaled 6,163 persons. That same year, Obira's administrators came up with the slogan "Obira is where Kodaira's dreams can come true." Their intention was to make Obira the giant-sized backyard of Kodaira, and a program has been under way since the early 1980s to encourage their urban counterparts to invest in forestland named "Kodaira's/Obira's forest" (Obira, April—May 1984). This is only one of the many similar "furusato reforestation" schemes jointly implemented by urban and rural sister-cities throughout Japan.

A dearth of eligible women has prompted the young men of Obira to seek brides from Kodaira. In this connection, it was significant symbolically that during the ninth citizens' festival the Obira town flag was carried by a group of girl scouts. After all, eligible young women from Kodaira have been urged to wear the Obira colors, so to speak.

The executive committee's report on the 1983 festival notes that the Obira sales corner turned a several-million-yen profit. Although the report cites only the figures for Obira, the same success probably was not enjoyed by the prefectural associations, as hinted by a prefectural association member and a DSP assemblyperson, who remarked that the associations operated in the red but "did not expect to profit anyway, since profit mongering is contrary to a festival spirit" (KGR, December 1982, 239). It seems that, whereas the participation of Obira is acknowledged and supported officially, the presence of the prefectural associations is taken for granted, despite Mayor Oshima's enthusiastic rhetoric during the first citizens' festival.