Gonds and Kolams

At the same time, the Gonds of the Adilabad highlands had already become used to meeting a shortage of their food grain by borrowing from merchants and moneylenders dwelling on the periphery of the tribal area. Thus had started the vicious circle of repaying borrowed grain by delivering to the creditor one and a half times the borrowed quantity as soon as the next harvest was reaped. Unless that harvest was exceptionally good the repayments usually resulted in the recurrence of the need to borrow grain for consumption later in the year.

Yet not all Gonds were compelled to depend on merchants to tide them over lean periods, and many reaped sufficient grain crops, mainly millets, to meet their domestic needs throughout the year. Food grain was then rarely sold, and cash requirements, such as the money needed for paying land revenue or buying clothes, were met by the sale of cash crops, usually grown only in small quantities. Oilseeds and castor were the main cash crops, for the large-scale growing of cotton is a relatively recent phenomenon. In Gond myths and epics there is no mention of cotton, whereas millet and rice both figure prominently.

A fundamental change in the agricultural pattern of the Gonds occurred in the first half of the twentieth century. Until then the Gonds had mainly cultivated the light, reddish soils on the high plateaux and gentle slopes on which they grew monsoon crops during the so-called

kharif season. As these soils could not be cultivated year after year, periods of fallow had to alternate with the periods of cultivation. So long as there was ample land available, this system of frequent fallows allowed the Gonds to grow adequate crops on light soils, and to leave the heavy, black soils in the wooded valley bottoms largely uncultivated. Some farmers, however, used stretches of black soil for growing rain-fed rice during the monsoon and wheat, sorghum, and pulses in the post-monsoon season known as rabi .

The reservation of forests and the shrinkage of the tribals' habitat caused by the incursions of non-tribal settlers compelled most of the Gonds to abandon the practice of frequent fallows and to take more and more of the heavy, black soils under cultivation. Shortage of land and the official policy of granting to individuals patta rights to clearly delimited plots of land, in the choice of which they often had no decisive say, led, moreover, to changes in cropping patterns and to the diversification of the economy of Gond farmers. The man whose patta land consists mainly of light, reddish soil has no other choice than to depend mainly on kharif crops, whereas the owner of heavy, black soils must inevitably concentrate on rabi crops. There are, of course, landowners whose holdings include both red and black soil, but few have sufficient land to permit them to continue the traditional practice of interspersing periods of tillage with extended periods of fallow.

Another change in the farming economy of the Gonds was caused by the allocation of individual holdings to the adult sons of farmers who had previously cultivated a large area with all the resources of manpower available in a joint family consisting of several married couples. Such farmers had been able to cultivate with as many as six or seven ploughs, and this had enabled them to spread their agricultural operations both spatially and chronologically, and to grow a variety of crops on their extensive holdings. Individual farmers cultivating about ten to fifteen acres are marginally less efficient, mainly because they cannot afford to take risks but must concentrate on the cultivation of the food crops on which they depend for their domestic consumption.

Yet another change occurred some ten to twenty years after the allocation of land on permanent patta to individual householders. This change was triggered by the establishment of commercial centres in the heart of the tribal area. Wherever non-tribals engaged in trade and moneylending settled, a cash-oriented economy was brought right to the door-step of many Gonds. The availability of novel commodities displayed in the newly established shops created among the tribals a craving for such goods. The only way of satisfying this craving was the production of crops of a high cash value.

Within the span of a few years, the entire cropping pattern of Utnur

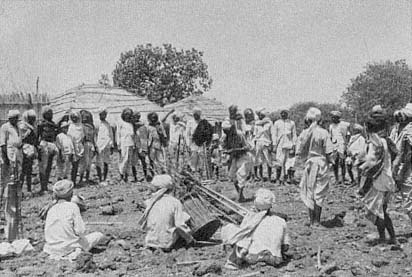

Gond village in the Adilabad highlands: the houses built of wood and bamboo

are thatched with grass; free-standing cylindrical grain bins are made of wattle

and covered with a mixture of mud and cow dung.

Taluk underwent a dramatic change. High prices paid for cotton and the possibility of speedily moving large quantities of this crop by lorry to the cotton market and rail-head at Adilabad transformed a food-producing area into a region concentrating on the growing of cotton. The availability of this valuable commodity brought increasing numbers of merchants, some from states as distant as Gujarat, to a region which twenty years earlier had been a tribal backwater.

One of the new commercial centres owing its rapid growth to the cotton boom is Jainur on the Utnur-Asifabad road. Until 1944 this locality was a deserted site in the midst of forest, and was then resettled by a few Gond families, who had moved there from such nearby villages as Marlavai and Ragapur. Within the past ten years it has turned into a flourishing market centre inhabited by numerous Hindu and Muslim merchants.

In the cotton-picking season in 1979–80, six trucks, each carrying one hundred quintals of cotton, left Jainur daily for Adilabad, and earlier in the year each of the six major cotton merchants had brought ten to twelve truck-loads of sorghum from outside the taluk for the purpose of giving advances of grain to the tribal cotton-growers. As a result of the good harvest, the price of cotton had dropped from the

Circle of Gond worshippers during the annual rites in honour of their clan god,

symbolized by a black yak's tail erected on a stave in the centre of the circle.

previous year's rate of Rs 450–500 per quintal to only Rs 330–50.

The merchants dealing in cotton were the same shopkeepers who supplied the Gonds throughout the year with sundry commodities, and their methods of trading deprived the tribals of the full profits from the change-over to cotton. For cotton brought to Jainur in cartloads, they gave the current price of Rs 330–50. Yet they did not pay cash on the spot, but gave the Gonds receipts and the promise to pay in two or three weeks' time after selling the cotton at Adilabad. Often they procrastinated the cash payment and tried to persuade the Gonds to accept part-payment in cloth or other consumer goods, and for these they asked prices much higher than those current in such towns as Adilabad or Mancherial. Those Gonds who had taken advances of grain, moreover, never received the entire cash value of their cotton when they delivered their crop. An even less favourable treatment had to be accepted by the numerous Gonds who had only small quantities to sell and brought the cotton by head-loads. Such loose cotton fetches a much lower price, which in 1979–80 was about Rs. 2.40 per kilogram, corresponding to a price of Rs 240 per quintal.

The replacement of food crops by cotton affects most parts of Utnur Taluk, and this is reflected in the very substantial imports of sorghum into an area which not long ago was self-sufficient in grain. Thus in

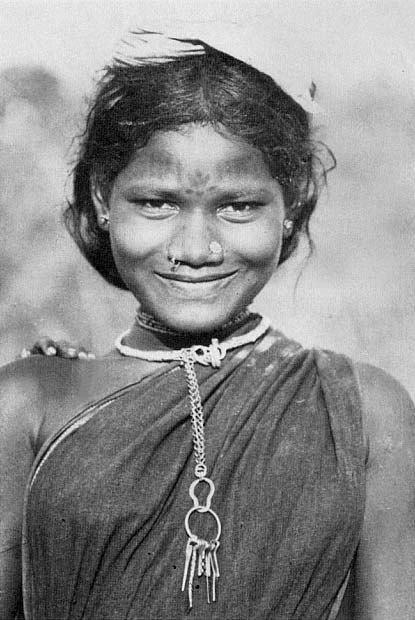

Gond woman of the Adilabad highlands; her forehead is tattooed,

and suspended from a solid silver necklace is a bundle of keys.

Gond wives have the keys to the store boxes and grain chests of the household,

and carry them always on their persons.

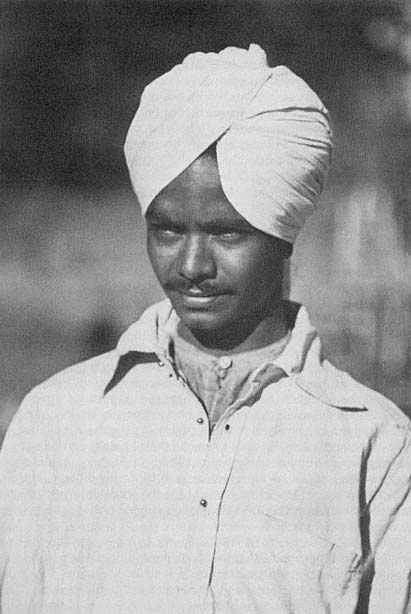

Gond of the village of Marlavai in Utnur Taluk; a white or red turban is the

traditional head-gear, but tailored cotton shirts, now universally worn, are

a modern innovation.

1979 in Narnur, another cotton market, alone two merchants between them brought 1,700 truck-loads of sorghum to their go-downs and from this stock supplied their Gond clients with the grain the Gonds now require because of their shift to the growing of cash crops.

The rapid change in the whole character of the agricultural economy has by no means brought only benefits to the Gonds. While those who possess ample land with heavy, black soil are likely to profit from devoting a large proportion of their holding to the raising of cotton, some Gonds owning only land of lighter soil are also tempted to grow cotton but may reap only a meagre crop. By growing the traditional food crops they would probably fare better. The cultivation of food crops, such as sorghum, also has the advantage that Gonds can estimate their domestic needs and if at all possible keep a store of sorghum to last them throughout the year. The cash obtained from the sale of cotton, on the other hand, is seldom spent for the purchase of a year's supply of grain but may partly be used up in buying luxuries previously beyond the reach of Gonds. After an exceptionally good harvest, there may be no harm in spending part of the cash received for cotton on items other than food grain, but in average and below-average years most Gonds just cannot afford to buy much more than essential clothes and food stuff sufficient to augment their own production of grain and pulses if this is inadequate to feed their families throughout the year.

The easy availability of such commodities as sugar, tea, cigarettes, and spirits in shops within walking distance of many villages, or even in small shops inside tribal villages, acts as a continuous temptation. While a generation ago tea and sugar were luxuries reserved for special occasions, many Gond families nowadays regularly purchase tea and sugar, and men who used to smoke their home-grown tobacco in leaf pipes now buy bidi or cigarettes. Wealthy men even own bicycles, and transistor radios are found in many of the larger villages. The cost of batteries alone for such radios and for the commonly used electric torches is a drain on a Gond's budget justifiable only in years when cash crops yield a good harvest.

The family budgets for 1976–77 set out in my book The Gonds of Andhra Pradesh (pp. 417–21) show that a wealthy man, such as Kanaka Hanu of Marlavai, had a cash expenditure of Rs 3,676, which included payments for land revenue and taxes, fertilizers, and wages for daily labourers. After the very bad harvest of 1978–79, only Kanaka Hanu and four other men of Marlavai expected to be able to balance their budgets, while all the other villagers foresaw that they would have to take loans of grain to meet their domestic needs until the next harvest. Kanaka Hanu was in a relatively favourable position because his holding contains several fields of heavy, black soil on which he grew ade-

quate crops of cotton and wheat, whereas those villagers whose land was of lighter soils saw both their food crops and their cotton crop fail.

In the following year there were good crops, and Kanaka Hanu reaped in kharif twenty quintals of rice, ten quintals of sorghum, two quintals of black gram, half a quintal of maize, half a quintal of oilseed, and twenty-five quintals of cotton. In January 1980 the rabi crops looked promising, too, and Hanu expected a yield of about thirty to forty quintals of sorghum and thirty quintals of wheat. As his domestic requirements of cereals were about fifteen quintals, he had a surplus of grain and could use the income from the sale of cotton—about Rs 8,250—to meet all his cash requirements. Hanu's land-holding, as well as his skill in managing the farm work, are exceptional, and the majority of Gonds have no surplus even in a good year.

A budget representative of a Gond of much more modest means is that of Kodapa Jeitu of Marlavai. Jeitu owns five acres in Marlavai and twelve acres in Jainur, which his brother cultivates on share. Jeitu cultivates with two ploughs; he owns one pair of bullocks and hires another from his brother Kasi, who lives in Jainur.

In 1976–77, he reaped the following crops:

|

His share of the field cultivated by his brother amounted to two quintals of cotton.

The sorghum lasted his family of seven heads for 11 months and the rice for 10 1/2 months. He sold castor at a rate of Rs 250 per quintal, and cotton for Rs 450 per quintal. He spent Rs 440 on clothes, Rs 250 on oil and spices, and Rs 240 on tea and sugar.

He took a loan of Rs 400 from a cooperative society, and he did not employ farm servants.

Tumram Lingu, one of the wealthiest and oldest men of Marlavai, who died in 1978, had owned nineteen acres of patta land in Marlavai and ten acres in Ragapur. His two married sons and one married daughter, deserted by her lamsare -husband, had lived in his house and cultivated with him. He had owned eight bullocks, eighteen cows, and four buffaloes.

In 1976–77, Tumram Lingu reaped the following kharif crops.

|

His rabi crops amounted to:

|

In Tumram Lingu's household there were then six adults and four children, and there was hence a surplus of grain over the family's needs. Gonds reckon that 1 1/4 quintals (i.e. 125 kilograms) of grain is sufficient to meet the average annual needs of one person.

The budgets of Kolams in possession of land are not different from those of Gonds, but there are relatively few Kolams who own economic holdings. One of these is Kodapa Jeitu of Muluguda (near Kanchanpalli), who owns twelve acres and cultivates with two ploughs. There are six persons in his household, including children.

In 1976–77, he reaped the following crops:

|

The domestic consumption of grain was ten quintals, i.e. the grain crop reaped, and the sale of cotton (Rs 1,200) and castor (Rs 125) more than covered the household's cash needs. Rs 700 had been spent on clothes, Rs 300 on oil, salt, spices, tea, sugar, etc., and Rs 31 on land revenue and tax on cash crops.

Besides those Gonds and Kolams who can balance their budget or even have a surplus, there are many who are seldom free of debt because their production of grain does not meet the family's consumption. Kanaka Dhami, a Gond of Kanchanpalli, for instance, was frequently in trouble. In the year 1975–76 he had to borrow from a merchant 2 1/2 quintals of rice. In 1976–77, his harvest was again inadequate, mainly because he had been ill and had hence delayed the sowing of the rabi crops, which consequently failed.

In the kharif season he reaped:

|

His cotton had failed completely and he had sown no other cash crop. The normal grain consumption of the household of six adults and children was ten quintals, and the shortfall was made up by earnings from casual labour. As Dhami had only one bullock he had hired one, and for this he had to pay sixty kilograms of sorghum as rent. But he had still to repay the previous year's loan of rice, and as he had no rice to give, his merchant demanded Rs 320 in cash. To raise this money he sold his only bullock for Rs 600. With the remaining money he bought a young untrained bullock for Rs 150.

The chances of a man like Dhami to free himself from indebtedness are slim, because after repaying the previous year's debt he has probably to borrow again to meet his family's needs for food and essential clothes.

No recent statistics regarding the incomes of Gond cultivators are available, but a study of seventy-four agriculturists in four sample villages of Utnur Taluk was undertaken in 1972 by D. R. Pratap,[1] and if we allow for inflation the findings retain some relevance. The average holding of the families investigated was 13.26 acres, and the cash incomes of the seventy-four agriculturists of the sample were as follows:

|

Attached labourers (farm servants) were paid an annual wage of Rs 400 plus five quintals of sorghum in the villages of Mutnur and Indraveli, and Rs 250 plus six quintals of sorghum in Lakkaram and Jainur.

Most agricultural labourers, who worked free-lance, had incomes between Rs 600 and Rs 1,400 per annum.

The average family income from all sources was calculated to be Rs 2,036.96, and the average per capita income was Rs 209.90, which compared unfavourably with the Andhra Pradesh average of Rs 545.29 in 1970-71.

The low incomes were explained by an analysis of the yield of the fields belonging to a random sample of Gond cultivators. The average yield of an acre under sorghum was 1.41 quintals, the yield of rice per acre was 2.36 quintals, and the average yield of cotton approximately 72 kilograms. Most Gonds do not have the capital to increase the yield of their land by applying chemical fertilizers and sowing improved hybrid seed. Hence agricultural production remains poor notwith-

[1] Occupational Pattern and Development Priorities among Raj Gonds of Adilabad District.

standing various development programmes, which have either remained on paper or been channelled mainly to the non-tribal inhabitants of the project area because these had greater pull with the officials responsible for the distribution of benefits.

We have seen that Gonds have become used to purchasing a number of consumer goods in shops or markets, and this may give the impression that their standard of living has risen in the past thirty years. This impression is partly deceptive, however, for the parents of the present generation had similar resources but spent them in different ways. While they bought few items of outside manufacture and no Gond would have aspired to owning such a thing as a bicycle, they were more lavish in entertaining and in the celebration of festivals and rites. The expenditure of food stuff on weddings and funerals was far greater than it is today, and the occasions for the employment of Pardhan bards were more numerous. Moreover, the rewards these artists received for their performances were much more generous than they are nowadays. The very fact that on many ritual occasions cows or bulls were slaughtered to provide meat for the entertainment of the participants indicates a different type of consumption, and the present addition of tea and sugar to the Gond diet must be weighed against the diminishment of the protein content by the exclusion of beef. This change also has a social aspect. Whereas the slaughter of a bullock provided meat for a large gathering drawn from several villages, a goat substituted as sacrificial animal can feed only a small circle of relatives and close friends.

A change-over to different but not necessarily more valuable items purchased by affluent Gonds is not an indication of a rise in living standards either. Previously Gonds would buy their wives and daughters heavy silver ornaments fashioned by local craftsmen, and many wealthy men wore embossed silver belts. Such items were not necessarily luxuries, because silver jewelry retained its value and in a crisis could be used as security for a loan from a moneylender. Today Gonds with cash to spare buy such articles as wrist-watches, electric torches, or the like, or they spend their money on pilgrimages to Tirupati, an unheard-of adventure thirty years ago. While some gonds now possess bicycles, men of the previous generation often owned ponies which they used exclusively for riding. These examples show that the change in the consumption pattern does not necessarily amount to a substantial rise in the standard of living.

A development which has caused a decline in living standards for a substantial percentage of Gond families is the loss of land to non-tribal settlers. In the 1940s, the great majority of Gonds were independent farmers, whether they held their land on patta or not, whereas today many have no land and no possibility of cultivating government land

on temporary tenure. Their only way of maintaining themselves is to work as farm servants or casual labourers on the land of non-tribal settlers who have displaced the original tribal population. This is a phenomenon not peculiar to Adilabad District or even to Andhra Pradesh alone, but is found in many parts of India. Thus a comparison of the data contained in the census reports of 1961 and 1971 shows that during the relevant decade the percentage of independent tribal cultivators fell from 68 percent to 57.56 percent, while the number of agricultural labourers went up from 28 percent to 33 percent largely, no doubt, owing to the mounting land alienation and eviction of tribals from their land.

It is obvious that the economic position of an agricultural labourer is greatly inferior to that of an independent cultivator, and that even Gonds who in the 1940s did not own land but cultivated government land on siwa-i-jamabandi tenure were far better off than agricultural labourers are today. Those landless Gonds who live in a purely tribal village and work for Gond landowners enjoy at least a social status not fundamentally different from that of other villagers, but Gonds working for non-tribal employers in villages where there are only a few other Gonds are among the most underprivileged tribals and in fact are no better off than Harijans.

The situation of the Gonds, Kolams, and Naikpods in Adilabad District, particularly in Utnur, has all the elements of a collective tragedy. Just at the time when the demand for cotton and the phenomenal rise in its price could have ushered in a period of mounting prosperity throughout the region of heavy, black soil which was so recently in tribal hands, the invasion of outsiders and a change in the political climate have shattered all hopes that the tribals would reap the benefit from their transition to cash crops. The transformation of a sorghum-, wheat-, and rice-growing area into an almost continuous expanse of cotton fields has brought about so rapid a commercialization of the whole economy that the conservative and largely illiterate Gonds cannot keep pace with the change-over to an entirely new system.

The very fact that land uniquely suitable for the growing of cotton is a magnet for advanced cultivators as well as merchants of all types makes it virtually impossible for tribals to remain in control of the land and its produce. Apart from the alienation of land discussed in chapter 2, there is also the penetration of the agents of commercial interests into the remotest villages. Traders who have their open shops and purchasing depots in such places as Jainur or Narnur have a network of agents, usually members of their own family, settled in many tribal villages. These agents keep small shops in which they stock matches, bidi , soap, tea, salt, and similar basic commodities, but each of them also gives advances for deliveries of cotton and castor, and in

this way secures for his principal the crops grown by the villagers, often well below the market price. Such petty shopkeepers also encourage barter transactions such as the exchange of cotton for groundnuts. In March 1979, when the Gonds were short of food after an unusually bad harvest, traders gave one kilogram of groundnuts for one kilogram of cotton, thereby obtaining cotton for about half the price current in Adilabad. The victims of such tricks were naturally not the substantial cotton growers who had several quintals to sell and found it worth their while to take their crop to Jainur or Adilabad, but the small Gond farmers, who had reaped perhaps only twenty or thirty kilograms of cotton and were easily duped to dispose of this as close to their homes as possible.

In Jainur, where a ginning mill has recently been installed, there are at the time of the cotton harvest huge mountains of the precious crop. Truck after truck, loaded with cotton, leaves for Adilabad. Here big business has gained a foothold in what only fifteen years ago was a purely tribal and economically backward area. Insofar as business acumen is concerned most Gonds and virtually all Kolams have remained "backward," and they are not yet capable of taking advantage of the possibilities which the cotton boom has brought to the area. Profits are largely mopped up by the middlemen and by traders to whom many Gonds have mortgaged their crops long before the cotton is even picked.

The unequitable division of profits can be gauged by the contrast between the life-style of the non-tribal businessmen settled in Utnur, Jainur, Narnur, and Indraveli and that of the average Gond villager. The former live in houses built of bricks and cement, fitted with electric lights and fans, own motor vehicles, and are at home in the district headquarters as well as in Hyderabad, while the Gonds continue to live in thatched huts with mud-plastered wattle walls and to wear simple clothes not very different from those their parents used to don.

The affluence of the merchants of Jainur becomes explicable if we compare the prices they charge tribals for their wares with those current in the market towns of other parts of the district. In the following list of prices in Jainur in January 1980, the prices for items of similar quality current in Chennur are given in parentheses:

|

The willingness of the Gonds to pay these excessive prices is sur-

prising considering the fact that a cheap bus ride would take them to places where they could make their purchases at much more reasonable rates. It can only be explained by their relative unfamiliarity with money transactions, which places the greater number of tribals at a disadvantage in their dealings with shrewd members of traditional trading castes.

The phenomenon of the growing exploitation of the tribal farmers by a class of immigrant nouveaux riches abetted in their domination of the local population by venal or lethargic petty officials is not peculiar to Adilabad. Similar situations have been observed in many areas and over long periods, and in some regions, such as Srikakulam District, violent reactions occurred when the long-suffering tribal peasantry saw their salvation in political movements led by Naxalite extremists. A gradually widening gap between the rich and the rural poor has been demonstrated by many investigations based on official All-India statistics which show that the percentage of rural households living below the extreme poverty line rose from 38 percent in 1960 to 53 percent in 1968.

The impossibility of ascertaining with any accuracy the extent of the land actively controlled and utilized by traders and moneylenders, even if not owned by them in law, is largely due to the connivance of minor revenue officials in illegal land transactions which make a mockery of the protective legislation to which the government is officially committed. Even visual examination of the undisguised accumulation of wealth by non-tribals in commercial centres such as Indraveli and Jainur and the equally blatant poverty of many a tribal settlement gives the lie to the official assumption that economic growth, even if initially set in motion by non-tribal agents, must ultimately also benefit the tribal populations. In Adilabad most tribals were in 1980 far worse housed than in the 1940s and early 1950s, and their chances of survival as independent cultivators have greatly diminished.

While the decline of the tribal prosperity is hardly surprising in an area exposed to a development by recent settlers which can only be described as "colonial," it is strange that this should have occurred at a time when, at least on paper, the government of Andhra Pradesh had sanctioned very large sums intended exclusively for tribal welfare, and was publicly committed to a policy of protecting the interests of the so-called "weaker sections" of the population.