3—

Capitalism Comes To the Diggings:

From Gold-Rush Adventure To Corporate Enterprise

Maureen A. Jung

Mention the stock market, the rise of the modern economy, or the growth of corporations, and most people think of the New York Stock Exchange and railroads in the eastern states. When it comes to U.S. business history during the nineteenth century, relatively little attention has focused on California or the growth of mining corporations. Recent historians have rarely examined the role of corporations and the growth of stock exchanges in the mining West, apart from Marian V. Sears's rare volume, Mining Stock Exchanges 1860-1930 , published in 1973.[1] California's unique contribution to the history of corporations has been neglected, in part, because of the long-standing interest in the more romantic, individualistic, and unorganized aspects of the Gold Rush. Thus, we still think of the Gold Rush as an adventure undertaken by individuals, although historians have recognized for more than a century that most emigrants traveled to California as members of companies.[2] Despite the importance of companies to the subsequent development of California's economy, we know relatively little about the pioneer firms that organized the Gold Rush. Similarly, we know little about the gold-field mining companies and corporations that superseded them. Few company records survive to tell the story. Apart from occasional mentions in diaries and letters, newspaper articles, government reports, and corporate filings, few reliable sources exist.[3] Still, if we examine such records from an organizational perspective, we can begin to construct a history of California's mining companies and their role in a larger transformation: the development of the modern corporate economy that emerged in California during the decades following the Gold Rush. This process was characterized by three developments: the rise of business corporations, the widespread ownership and trade in corporate securities, and the formation of stock exchanges to organize investment.[4]

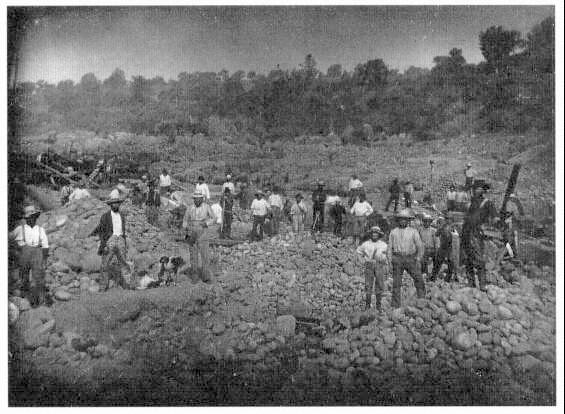

While railroads drove economic expansion in the eastern United States, mining

A company of miners at Lincoln poses for the pioneer California daguerreotypist William Shew

sometime in the early 1850s. Even before the emergence of the heavily capitalized corporations that

came to dominate mining in the Golden State, fortune hunters formed associations to undertake

large-scale operations, such as turning a river out of its bed to expose the rich sand and gravel

below. Courtesy Bancroft Library .

was the first industry in the West to widely adopt the corporate form of organization. Despite a history of animosity toward business corporations in the early nineteenth-century United States, a speculative boom occurred in California mining between 1851 and 1853. Dozens of mining corporations were formed. They attracted investment capital from the East Coast and even from Europe. During the 1850s, California mining was quickly transformed from individual adventure to an industry organized by corporations and worked by wage laborers. Although the early mining corporations succeeded in attracting outside investment, few produced profits or paid dividends. Disappointed investors quickly abandoned the California mines, which for years would have trouble attracting outside capital.

In 1859, however, interest in mining corporations surged once again. Discovery of gold and silver on the Comstock Lode triggered a mining industry boom in which

thousands of corporations were formed. This sudden growth fueled public interest and promoted widespread trade in mining securities, as California became the first site of broad public stock ownership and intense share trading. Such investments funded important advances in mining and initially revived California's stagnant economy. During the 1860s and 1870s, however, corporate insiders used the securities market as an organizational mechanism to wrest control over mining properties. Corporate power won out over individual rights, as insiders manipulated share prices, bilked investors, and drained companies. These activities diverted funds from more productive investments, injured workers' livelihoods, and damaged the economy as a whole. For all the imperfections of this system, however, these mining corporations played a central role in California's economic development and in the advance of the mining West.

Business Organizations Prior To the Gold Rush

Mining was a minor industry in the agriculture-dominated eighteenth century, though small-scale mines operated in several eastern and north-central states before the Revolutionary War. While a few corporations for mining and other purposes were established by 1800, most people in the United States viewed government-chartered business corporations with suspicion.[5] State laws made incorporation for private profit a difficult process, which initially required passage of a special legislative act; they also placed severe restrictions on corporate size and span of operations.[6]

Partnerships were the dominant form of commercial enterprise in this country for much of the nineteenth century, adequately serving business interests from "small country storekeepers to the great merchant bankers.[7] Larger business ventures often organized as joint-stock companies, a type of group partnership. Joint-stock companies offered two distinct advantages over traditional partnerships: ownership interest was divided into shares and the death or withdrawal of one partner did not end the partnership.

Unlike corporations, which were rooted in state authority, partnerships were based on individuals' freedom to associate, to pool their energies and capital for mutual advantage. This freedom was understood as a "right of business bodies, not . . . a privilege to be granted or withheld" by government rules.[8] Partners participated in company operations on an equal footing. They maintained direct control over their ownership interests and often voted on company decisions. By contrast, corporate shareholders possessed only indirect, limited control over their investments—the ability to sell their shares, should they find a willing buyer. Despite the advantage of greater control, however, partnerships had one great drawback: each partner was fully liable for debts incurred by the company, an onerous burden in large-scale ventures.

Large-scale businesses such as railroads, mines, banks, and insurance companies

pressed the state legislature for broader rights, including the ability to organize under general incorporation laws. Gradually legislatures relented, extending the term of life allowed corporations and limiting shareholder liability.[9] Such changes gave corporations several distinct advantages over partnerships, which also made corporate stock a more attractive investment. Nonetheless, early shareholders were vulnerable to assessment calls when company management decided additional investment was necessary. Shareholders who neglected to pay the levied assessment forfeited their stock, and ownership reverted to the company.

As statutory limitations gradually loosened, growth in the number of corporations aroused public concern and stimulated popular support for government regulation of corporations and corporate securities.[10] For decades, people viewed corporations as monopolies, as economic historian Clark Spence put it, "enemies of individual enterprise."[11] It is not surprising, then, that entrepreneurs formed relatively few corporations in the eastern states prior to the Civil War. Between 1800 and 1843, for example, total incorporations in six eastern states reached 3,249, only seventy-one of them formed under general incorporation laws, the rest by special charter.[12] The Panic of 1837 sharply curtailed incorporations, as thousands of banks and businesses failed. The ensuing depression continued well into the 1840s.

Organizing the Gold Rush: Pioneer Mining Companies

Although rumors of the gold discovery in California reached the East Coast in mid-1848, it was President James Polk's December message to Congress that riveted public attention. He affirmed the rumors were true. There was gold in California, on public land, and free for the taking. Many men resolved to hurry to the gold fields, acquire a quick fortune ("strike it rich"), and return home to establish a respectable business. Across the country, men organized partnerships and joint-stock companies and made plans to seize their riches. Dozens of elaborately organized companies were ready to sail before a month had passed. On January 24, 1849, the New York Herald listed forty-seven companies, with a total of 2,499 members, ready to leave.[13] A few days later, the Herald reported that while a few impetuous individuals had already left for the gold fields alone, most men planned to travel as members of companies. In what was surely an exaggeration, the newspaper stated that already 10,001 companies had "sprung up like mushrooms—all a lot alike," and listed thirty-two articles typically adopted by such companies.[14]

Like other partnerships, equality was the organizational principle upon which these companies were founded. Members of the Perseverance Mining Company of Philadelphia, for example, vowed to "pursue such business in California, or else where, as shall be agreed upon by a majority of its members, and that the expenses

of the company shall be mutually borne and the profits equally divided. . . . We hereby pledge ourselves, to support and protect each other in case of emergency and sickness, and in all cases to stand by each other as a band of brothers."[15]

Members usually elected officers and voted to determine company actions. Members of larger companies also worked together under an agreed-upon division of la-bon While not all companies published formal articles of agreement or printed membership shares, members shared a unity of purpose. They joined together to improve their chances of success as they journeyed to a distant and, to them, unknown land to engage in mining, an occupation about which almost all were entirely ignorant.

Company organizers were often community leaders, who solicited members by newspaper advertisement, handbill, or word of mouth.[16] Members, often from a single locale, commonly had to forswear alcohol, strong language, and gambling. Company size varied greatly, from as few as three to over one hundred members. Share prices in the companies also varied widely, from as little as $50 to more than $2,000. After formation, members met regularly to plan their California expedition. Money collected through the sale of company shares went to purchase and outfit a ship or buy wagons and mules or oxen for the journey. Companies traveling by sea frequently bought supplies intended for sale in California. Many took along elaborate mining contraptions they later found to be useless. Not surprisingly, companies from eastern seaboard states were more likely to sail to California around Cape Horn or via the Isthmus of Panama, while those from the western states (Wisconsin, Illinois, Arkansas, and Missouri) usually traveled overland by wagon train or pack mule.

Despite all their careful plans and businesslike approach, few gold-rush adventurers were prepared for the planning and provisioning necessary on a journey that could last six months or more. Few anticipated the adventure ahead, or the ordeals and downright tragedies so many of them would face. The story of the Gold Rush unfolds in the changing landscape of companies struggling against their environ-Dents and among themselves, whether they circled Cape Horn, crossed Panama, or traversed the continent. They faced inestimable odds, and few companies survived the journey intact. Of those that did, most voted to disband shortly after arrival in California. While some men set out alone for the diggings, many chose to travel with a partner or small band of companions as they began their search for fortune. Although most pioneer mining companies were short-lived, they served as important models for companies the adventurers established in the diggings.

Reorganizing the Gold Rush: Mining Companies in the Gold Fields

In the absence of established cities and towns, mining districts became the basic political unit in California's gold fields. Although they initially had no legal standing,

Handbill of the California Emigration Society, Boston, advertising passage to

California "in a first-rate Clipper Ship." Published in 1856, it promoted the

economic opportunities to be found in the new El Dorado. On the verso, notice

was made of mining companies offering wages of "$4.00 per day and board to

steady workmen," testifying to the transformation of gold mining from individual

adventure to corporate enterprise. Courtesy Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif .

codes were framed by the miners of each locale, which regulated both social behavior and mineral rights within the district. So fundamental did these miners' codes become to the regulation of mining that both state and federal governments refused to intervene for nearly two decades. While miners' codes varied across California's mining districts, two elements were central to nearly all of them: discovery and work. The man who "discovered" or "claimed" an area, then marked it and recorded the location, acquired its mineral rights. To retain these rights, the codes required miners to work their claims steadily, as many as twenty days per month in some districts. Most of the early codes limited claim size to what a single person could mine alone, initially 100 to 150 square feet. Size limits and work requirements effectively prevented absentee ownership and the monopoly of mining claims, both of which were strongly opposed by most miners.[17] It is no surprise, then, that in his study of western mining camps, historian Charles Shinn judged that buying, selling, and speculating in mining claims were activities that were probably foreign concepts to the early gold-rush miners.[18] Individual rights were paramount. As miner Samuel Upham observed, "no chartered institutions have monopolized the great avenues to wealth. . . . everyone has an equal chance to rise. . . . Neither business nor capital can oppress labor in California."[19] Equality of ownership was the principle underlying the mining codes.

Within this context, working miners, a majority of the early population in the mining districts, viewed one another in a particular light. "All men who had or expected to have any standing in the community were required to work with their hands, labor was dignified and honorable," wrote early California historian Theodore Hittell, "the man who did not live by actual physical toil was regarded as a sort of social excrescence or parasite."[20]

Yet things changed quickly in the gold fields. By April 1850, John Banks, a former member of the Buckeye Rovers, an Ohio company, described what typically happened in each new mining camp. Newcomers arrived steadily, forming "almost one continuous stream of men. Every place is snatched up in a moment. This canyon is claimed to its very head, nearly 20 miles, each man being allowed but 20 feet."[21] As the number of gold seekers outpaced the number of claims discovered, and as the technology and capital needed to work the diggings exceeded the resources of individual miners, they formed partnerships and joint-stock associations and worked together. California historian and philosopher Josiah Royce referred to this organizing tendency as a unique attribute of the American character, "a natural political instinct," yet it was based on practical experience.[22] As gold-rush traveler and miner J. D. Borthwick observed, despite the "spirit of individual independence" many Americans proclaimed, "they are certainly of all people in the world the most prompt to organize and combine to carry out a common object. They are trained to it from their youth in their innumerable, and to a foreigner, unintelligible caucus-meetings, committees, conventions, and so forth."[23] To men already accustomed to working to-

gether for mutual advantage, forming companies to pursue mining operations seemed an obvious alternative. Indeed, the miners had little choice, as earnings fell steadily through the early 1850s. Estimated at about $20 per day in 1848, miners' daily wages dropped from about $16 in 1849 to $10 in 1850 and to $8 or less in 1851, and down to about $3 a day between 1856 and 1860.[24] At the same time, another change took place. Between 1848 and about 1850, miners' "wages" referred to earnings from a day of mining, whether the individual worked on his own account or was employed by a company.[25] By 1851 fewer men mined "on their own hook," and the term took on its modern connotation: the earnings of wage laborers.

Mining underwent a transformation. From individual adventure and competition, mining operations began to resemble factories in the eastern states and Europe, with distinct divisions of labor and differential pay scales. While competition over claims increased and miners' wages fell, easily acquired gold was fast depleted. On July 15, 1851, San Francisco's leading newspaper, the Alta California , appeared pessimistic about prospects for the industry: "Now we hear of the complete exhaustion and abandonment of many of the diggings." Miner John Banks felt the stress acutely: "We have left our claim like hundreds of others. . . . Misery loves company; we have plenty. . . . Men are frightened, some starving, confused, not knowing what to do, where to go. . . . Prospecting is a necessity and a dangerous business."[26]

Technological advances, such as the rocker, the sluice box, and the long tom, permitted miners to work more efficiently. By instituting a division of labor, miners were able to exploit their claims more systematically than was possible working alone. While the work was rigorous, costs were relatively low given the labor-intensive methods of placer mining. Gold-field mining companies, mostly partnerships and joint-stock companies, shared many similarities to the pioneer mining companies in which so many had emigrated. Both were voluntary associations in which members participated equally or proportionally in the labor, costs, and profits, if any. Members exercised voting rights on company decisions, worked under an elected foreman, and operated on the principle of joint shares.[27] Claims turned over quickly, as miners made a discovery, swarmed in to exploit it, and moved on. Mining partnerships and companies formed quickly and could be dissolved just as quickly when things went wrong, as they often did. Rampant rumors sent miners scrambling from one reputed bonanza to the next. A few lucky souls struck pay dirt, but most struggled, subsisting on whatever came to hand.

Though many gold-rush adventurers returned home with empty pockets, others applied themselves to solving the technical and organizational problems of mining for gold. To solve the major obstacles to finding, extracting, and processing gold, miners developed three new large-scale approaches to mining during the early 1850s: river, quartz, and hydraulic mining. Each approach had its own particular set of costs. In river mining operations, supplies and building materials for flumes, dams, and ditches

Miner Prospecting , a hand-colored lithograph designed and drawn by Charles Nahl and

August Wenderoth, illustrates the archetypal California gold seeker of romance and legend.

The two artists, who spent the summer of 1851 mining at Rough and Ready in Nevada

County, portrayed the heavily armed and well-outfitted Argonaut as solitary, self-reliant, and

resourceful. Published in San Francisco in 1852, the print contributed to the popular image of

the gold hunter that has endured for a century and a half. Courtesy Bancroft Library .

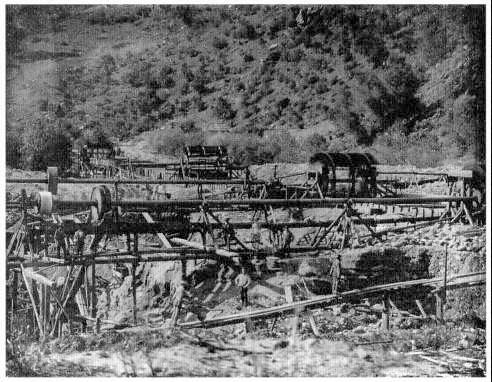

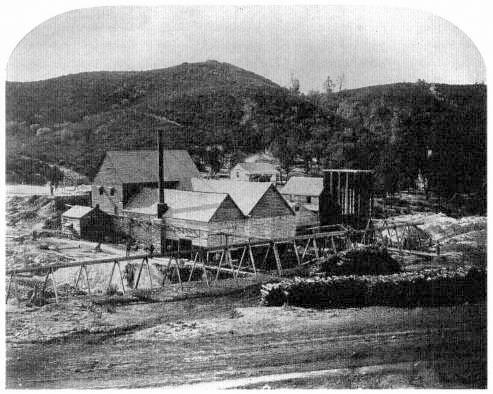

River mining, about 1852. A dam has been constructed upstream, diverting the watercourse

into a flume, visible on a diagonal cutting across the daguerreotype image. The large water

wheels powered by the flume turn huge driveshafts, connected by leather belts to pumps,

which keep the exposed riverbed dry. Though highly speculative, river mining was widely

practiced, the first of the large-scale entrepreneurial enterprises pursued in the diggings. In

1853 several companies working independently spent three million dollars turning twenty-five

miles of the Yuba out of its bed. Courtesy Bancroft Library .

consumed money. Similarly, hydraulic operations required huge quantities of water delivered to the mine site, while quartz mining involved extracting gold through deep shafts, then crushing and processing the ore, all expensive undertakings, particularly when the technology available then allowed for the recovery of so small a percentage of the gold. While technology presented formidable challenges to the miners, lawsuits over disputed claims and water rights became increasingly common. For years to come, law and water developed as subsidiary industries to mining.

Fighting lawsuits, building flumes and ditches, and developing large-scale quartz mining operations all required capital. Despite rising gold production during 1850 and 1851, the large number of men and the growing difficulty of extracting the gold led to changes in social relations in the gold fields and transformed the organization of mining operations. Until 1851, most money invested in California mines was pro-

duced by the miners themselves. With the changes and experiments with new technology and high interest rates on borrowing, the need for outside investment was apparent if the industry was to grow. At the same time, some observers viewed the organization of joint-stock companies and corporations as a positive sign that more stable industrial organization was emerging to displace the turbulent era of gold-rush adventurers. Felix P. Wierzbicki, who described his tour of the gold fields in a widely quoted pamphlet, California as It Is & as It May Be, Or a Guide to the Gold Region , predicted that "When this gold mania ceases to rage, individuals will abandon the mines; and then there will be a good opportunity for companies with heavy capital to step in; there will be enough profitable work for them; and it is then that the country will enter on a career of real progress, and not until then."[28]

Launching a Market for Corporate Securities

As some miners struggled to advance industrial mining and establish a scientific approach to mine operations, others turned their attention to the financial side of corporate organization. The most immediate, and notorious, manifestation was a speculative boom in quartz mining that rocked the state's economy between 1851 and 1853. California miners formed corporations, hoping to raise funds by selling corporate stock. To be successful, however, they had to overcome the legacy of suspicion attached to corporations and corporate securities.

California's state constitution followed the lead of several other states with regard to corporations. Chapter 128 of the state's legal codes, "An Act Concerning Corporations," was a general corporation law passed by the state legislature in April 1850. It permitted companies to incorporate without seeking approval of a special act of the legislature, although it prohibited bank corporations altogether. The law held shareholders "individually and personally liable" for a proportional share of corporate debts. In other words, those who invested in corporations were required to pay assessments levied by corporate management when additional funds were needed to keep the company afloat. These were not ideal conditions under which to attract investors, yet the need for outside investment was clear, if the mining industry was to revive and expand.

Until the rise of quartz mining, outside investors showed scant interest in California mining companies. River mining companies grew primarily through investments from and efforts by company members. Additional labor by the partners often compensated for a company's lack of ready cash. Quartz mining, the high technology of its day, was altogether different. Outsiders recognized quartz mining as a complex, capital-intensive activity that required sophisticated machinery and the application of scientific processes to free gold from the quartz. Quartz mining captured the imaginations of miners and outside investors alike, and heightened inter-

est in the trail of gold. The discovery of what appeared to be rich quartz deposits in Nevada County stimulated a rush to locate quartz claims in 1851. In the picturesque language of Edwin F. Bean, who compiled the 1867 Nevada County history and directory, "prospectors were running over the hills in every direction" in search of likely spots to stake claims.[29]

Though few miners knew anything about quartz mining or processing, this lack of knowledge failed to inhibit their enthusiasm for organizing new ventures. As some miners transformed their companies into corporations and began to market shares to the public, many others sold or abandoned their claims, recognizing not only the technical problems, but also the difficulty of raising the money necessary to develop a quartz mine.

Just as newspapers sold the Gold Rush to adventurers in 1849, corporate promoters used the press to attract investors. They had to convince the public that mining was no longer a reckless adventure but instead was an industry conducted by sober businessmen with practical experience. Promoters contributed newspaper articles, wrote letters to editors, and served as sources for the press, and the papers responded with optimism. As the San Francisco Morning Post reported on October 13, 1851, "quartz mining in this country is no longer an experiment." In addition to marketing through newspaper advertisements, some promoters produced elaborate stock prospectuses for potential investors to examine.

Such promotional efforts paid off, if only temporarily. While no one knows with certainty the number of mining companies formed during the 1850s, the number of mining corporations can be estimated with some accuracy from copies of articles of incorporation filed with the California secretary of state.[30] Table 3.1 shows the number of corporations formed each year in California during the 1850s. Predictably, in a decade during which mining companies accounted for 75 percent of incorporations, the very first corporation was a mine: the California State Mining & Smelting Company. Organized and operated in Santa Clara County, this company incorporated with $100,000 in capital stock.[31] California's second corporation, the Mariposa Mining Company, was quite different. With $1 million in capital stock, the sheer size of the company must have been mind-boggling to many early investors. Incorporated by seven San Francisco residents, who conducted company business from the city, mining operations took place in Mariposa County, on land leased from John C. Frémont.[32] Company prospects seemed bright, and in 1851 Mariposa Mining Company securities were traded on both the London and Paris stock exchanges.[33] In a departure from earlier practices, its company organizers were not working miners. They held interests in other mining corporations; at least two acted as attorneys; and the company was closely linked with a leading San Francisco bank association, Palmer, Cook & Company. Despite such connections, the Mariposa Mining Company was unable to solve the technical problems related to quartz processing. Like

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Mount Ophir Mill, located at the town of the same name, a half-dozen miles west of the

county seat of Mariposa, within the boundaries of the extensive land grant acquired by John

C. Frémont. In 1858, the year before Carleton E. Watkins took this photograph, there were

twenty-four steam-driven stamps in operation at Mount Ophir. All that remains today of this

once-vital mining center are a few crumbling ruins and colorful memories of days of gold.

California Historical Society, FN-24671 .

so many early mining companies, it was also plagued by lawsuits. Mariposa's legal disputes over mineral and water rights spanned a number of years and a variety of succeeding companies.

Just as California's legal profession developed in tandem with mining, banking also evolved as a subsidiary industry. Members of the leading bank associations were frequently aligned with the leading mining corporations. The linkage was natural. The banks handled both transportation and deposit of the gold produced in the mines. They frequently provided short-term loans for mining companies and often served as trustees on corporate boards.[34]

Table 3.1 shows that promoters formed twenty-six mining corporations in California during 1851, the first year of the quartz boom. Capital stock in these companies ranged from $100,000 to $1 million. While there is no way of knowing how

much money was actually paid in to these corporations, it is clear that investors overall poured millions into mining corporations. Nevada County was the center for quartz mining during these early years. Thirty-three mining corporations, 42 percent of the total organized during the boom years of 1851 and 1852, were located in Nevada County. Along with the corporations, stamp mills to crush the quartz were also built, and, by November 1851, eight mills operated around the clock in Nevada County, and seven more were under construction.[35]

Though Nevada County miners worked hard to develop quartz mines and mills, most of the early attempts were failures. The first mill builders found to their dismay that their ore-crushing stamps wore out after just a few months. Others had trouble importing machinery; and much of the machinery that arrived at the mines was worthless in actual operation. Once again, many sold out or abandoned their mining claims after exhausting both money and hope. In the fall of 1851, for example, John A. Collins & Company completed a ten-stamp mill that operated around the clock. Capable of crushing 100 tons of ore per day, this mill was considered one of the finest built to that date. Before the year was out, however, Collins & Company sold out to the Grass Valley Gold Mining Company; a corporation formed on July 25, 1851, with $100,000 in capital stock and the option of increasing to $250,000, should additional capital be needed. All five founders of the corporation listed San Francisco as their residence.[36]

Relying on advantageous relationships with the press, letters and stories about the company appeared not just locally, but also in New York City. Company president Jonas Winchester was a former business associate of Horace Greeley, publisher of the New York Tribune . For a time in 1850 and in 1851, Winchester lived in New York City to promote interest in quartz mining and to advance the sale of his company's stock. During this time, he also assisted James Delavan, secretary of the Rocky-Bar Mining Company, who also journeyed to New York to promote his company. Both men wrote often and authoritatively on the subject of California mining, usually neglecting to reveal their financial interests and occasionally omitting to mention their names. On March 9, 1850, for example, a letter published in the Tribune and signed "J.W." reviewed the prospects for quartz mining in California. "With capital, machinery, and a proper scientific knowledge of mining, which must be rapidly introduced," the author wrote confidently, "you need not fear the supply of gold being less than thirty to fifty millions a year in this generation."[37] That same year Delavan anonymously published Notes on California and the Placers: How to Get There and What to Do Afterwards , an entertaining description of a trip to the gold fields and travel in the mines, which included an admiring account of the Rocky-Bar Mining Company and its rich prospects, without mentioning the author's affiliation with the company.[38] Such publicity efforts attracted public attention as well as investors, as more California mining companies chose incorporation to raise capital and increase the scope of their operations.

In 1852, the number of mining corporations formed in California nearly doubled, to a total of fifty-three. On January 2, 1852, trustees of the Grass Valley Mining Company voted to increase the company's capital stock to $250,000. The same day, four of these trustees joined John Collins and formed another corporation, the Manhattan Quartz Mining Company. Horace Greeley himself was listed as secretary and treasurer of the company, while Collins served as president. To attract investors, each company issued an elaborate stock prospectus. By that time, the Grass Valley Mining Company held more than four hundred mining claims, while the Manhattan held sixty-four, a significant departure from the earlier principle of one claim per miner. Each prospectus quoted from the law, from published articles, letters, and reports, and cited production figures as evidence of the soundness of their undertaking and the lucrative dividends investors could anticipate. According to the Manhattan Company prospectus, "shareholders [will] reap a golden harvest.[39]

Investors contributed millions to California mining operations between 1850 and 1853. Increasingly, investors from afar—Sacramento, San Francisco, New York City, Boston, and abroad—purchased stock in California's mines. Foreign corporations were also formed to undertake mining operations in California. British investors, for example, sank nearly $10 million into shares of California mining corporations, and, by 1853, British promoters organized thirty-two corporations in London to mine for gold in California.[40]

Though dozens of California and foreign corporations successfully attracted investment capital, developing efficient ore-processing methods and machinery proved to be a more intractable problem. At the same time, lawsuits also consumed a significant proportion of the gold produced. Few of these early corporations paid out even a single dollar in dividends, provoking widespread disillusionment and an almost immediate reaction: the collapse of outside investment in California mining in 1853. Thereafter, through the end of the decade, California mining corporations had trouble raising investment capital.

Nonetheless, California miners continued to form corporations and to invest their own capital in mining operations, frequently buying out earlier works and attempting to run them more efficiently. The end of California's first wave of corporate mining speculation was not the end of mining corporations, by any means. As Table 3.1 shows clearly, the number of mining corporations grew throughout the 1850s, accounting for fully three-quarters of California's corporations formed during the decade. The growth of corporate mining meant fundamental changes in the gold fields that did not escape notice of the press. On June 11, 1858, Sacramento's Daily Union described this transformation as a "complete revolution" in "the methods and means applied to mining," leading to the concentration of mine ownership among "men of means who have employed others to mine for them."

Despite widespread company failures and continued uncertainty about the in-

dustry, the boom of 1851 through 1853 illustrated an important business principle: incorporation was a means for channeling investment dollars into mining company operations. In that sense, these corporations served as a force for stability and a catalyst for growth for mining and its subsidiary industries, particularly in the long run. In the short run, however, they proved destabilizing, funneling money into ill-conceived ventures and diverting funds from more productive uses.

For the remainder of the decade, outside investors shunned California mining corporations. Meanwhile, gold production fell steadily from its peak in 1852 at $81 million to $46.8 million in 1859. The California economy languished at the end of the decade, seemingly awaiting the next big strike that would stimulate manufacturing and boost commerce. Suddenly it happened: in 1860, a wave of new mine incorporations propelled rapid expansion of the California economy.

Organizing a Corporate Economy

The restructuring of mining that began during the early 1850s was completed with the rise of corporate mining on what came to be known as the Comstock Lode in Nevada (then part of Utah Territory) during the 1860s. Miners who crossed the Sierra from California had prospected the area for nearly a decade, barely eking out a living. Then, in June 1859, a party of prospectors discovered a rich ore deposit containing gold and silver.[41] Quickly forming a company, the partners worked their claim. News spread fist, and miners from throughout the West, especially Californians, swarmed to the Comstock. Problems emerged quickly. The mining codes adopted on the Comstock, modeled after California's, ensured that conflicts would develop over claim boundaries and guaranteed that lawsuits would follow. This was hardly surprising in an area that stretched less than three miles, where nearly seventeen thousand claims were quickly recorded.[42] A lively trade in mining claims developed immediately. In his detailed study of the Comstock Lode for the U.S. Geological Survey, Eliot Lord noted that "without and within doors a fever of speculations raged without check. Sales of claims for money were comparatively rare, but barters were incessant. . . . Paper fortunes were made in days.[43]

The original claimholders, lacking both the knowledge and the capital to develop large-scale quartz mining operations, sold out. The buyers included some familiar names: Judge James Walsh, Joseph Woodworth, and George Hearst, all from Nevada County, California.[44] After forming a partnership, the Ophir Mining Company, they undertook the first systematic mining operations on the lode. Before long, they sent a shipment of ore to San Francisco for assay. On November 16, 1859, the San Francisco Alta California reported that the ore revealed an estimated $1,595 in gold and $4,791 in silver per ton, fabulously valuable by California standards. And California standards prevailed on the Comstock. Initial ore assays helped cre-

ate the impression that the Comstock mines would prove rich beyond belief and produce for centuries, similar to the fabled mines of Mexico, Bolivia, and Peru.

As California miners and financiers bought up Comstock properties and established corporations, speculation in mining claims quickly gave way to speculation in mining stock. On April 28, 1860, Hearst and his partners incorporated their mine in California to create the Ophir Silver Mining Company. With $5.04 million in capital stock, the Ophir was the largest corporation in the West. Others quickly followed suit. By the end of 1860, thirty-seven additional Comstock mines were incorporated in California, which triggered a wave of incorporations never before seen in this country. More than one thousand mining companies were incorporated in California that year.[45]

All this activity attracted intense interest, as more and more people hoped to make money in mining stock. While some hoped for more reliable financial reporting, most appeared more interested in the speculative prospects of mining securities.[46] The increase in transactions and opportunities for the collection of brokerage commissions led to the formation of the San Francisco Mining Stock and Exchange Board on September 1, 1862. Although founders of this exchange were branded in the press as the "Forty Thieves," the organization prospered. By 1864, six new mining stock exchanges were formed in San Francisco, and nine in the vicinity of the Comstock Lode, along with exchanges in Sacramento, Stockton, and Marysville.[47] Meanwhile, the number of mining corporations skyrocketed; 2,933 were formed in 1863 alone, 84 percent of them gold and silver mines.[48] California banking historian Ira Cross concluded that "especially during 1863 did it become the normal, expected thing for any party possessing a small mining claim to organize a corporation of large proportions and to sell the stock at astounding prices to a gullible and speculative public."[49] Securities of the Comstock corporations dominated the market. Strangely enough, stock speculation increased, due largely to the production of a single mine, the Gould & Curry[50] Few of the other mines produced profits or paid dividends. Yet, as miners on the Comstock Lode wrestled with technical problems of extracting and processing the complex amalgam of gold and silver found there, financiers and promoters developed sophisticated new methods of organizing companies and manipulating stock transactions. By comparison, California mines continued to have difficulty attracting investments.[51] California's gold mines were much smaller operations. They required far less operating capital than the gold and silver mines on the Comstock Lode and offered fewer opportunities for speculation on the stock market. As Table 3.2 shows, California gold production continued to decline into the 1860s, after which it remained relatively steady, between $15 and $24 million through 1878. While gold and silver on the Comstock Lode did not exceed California's gold output until 1873, the annual transactions on the San Francisco Mining Stock and Exchange Board alone exceeded $100 million a year between 1871 and 1877.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Following the practices adopted a decade earlier, corporate promoters on the Comstock Lode issued elaborate prospectuses that they distributed far and wide. They also enlisted the press in campaigns to sell stock to the public, and with huge success. For the first time in the history of the United States, stock market participants represented a broad cross-section of social classes.[52] San Francisco's Mining and Scientific Press observed that it was the rare person who did not own at least a share or two of mining stock.[53] According to the publication, "the market extends everywhere; the buyers and sellers of stock include the millionaire and the mendicant, the modest matron and the brazen courtesan, the prudent man of business and the gambler, the maidservant and her mistress, the banker and his customer.[54]

As had been the case a decade earlier, close ties developed between banks and mining corporations. Banks managed mining corporation accounts, arranged payrolls, made short-term loans, lent money for the purchase of mining stock, and accepted mining stock as collateral on loans.[55] When production dropped at the Comstock mines, San Francisco banker William C. Ralston and his agent, William Sharon, stepped in to take control. Indeed, close relations between the leading bank on the West Coast, San Francisco's Bank of California, and the Comstock mining corporations lent an air of respectability to mining stock transactions. At the same time, it gave Sharon and Ralston direct access to financial information on local businesses, which they used to advance their own interests.

Enacting a liberal lending policy, Ralston and Sharon lent money to independent mills, but then starved them of ore to process. Without income from ore processing, mills were unable to repay their loans, and Ralston and Sharon gained control over most mills in the area, which they then consolidated as a single corporation, the Union Mill and Mining Company. They held onto these shares, rather than distributing them through the stock market.[56] At the same time, they extended their control over both mines and mine suppliers, which continued to operate as formally distinct corporations.[57] Relying on advance knowledge about progress in the mines, Ralston, Sharon, and their allies, known as the "Bank Crowd," fed rumors to the press and timed assessment calls and stock sales to drive prices up or down according to their plans. According to early historian John S. Hittell, "every trick that cunning could devise to make the many pay the expenses, securing to the few the bulk of the profit, was practiced on an extensive scale.[58]

This broad control, even backed by the financial power of the Bank of California, could not guarantee perpetually growing production at the Comstock mines, however. Nor did it prevent the rise of rival groups to challenge the control wielded by Ralston and his allies. Twice during the 1870s, successful campaigns were waged through the stock market to wrest control of particular mines.[59] Alvinza Hayward and John P. Jones broke away from the Bank Crowd and gained control of the Crown Point and Savage mines. At about the same time, four Irish immigrants soon known

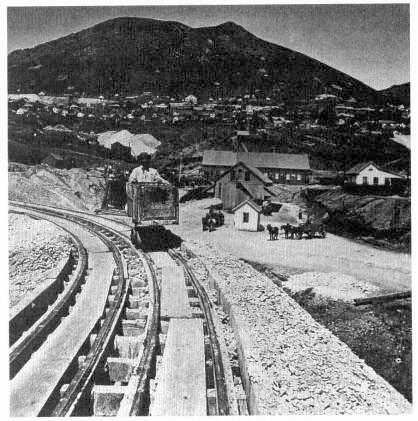

Mount Davidson, on the far western reaches of Nevada, looms above a

miner at the lower dump of the Gould & Curry Mine in 1865. Although the

Comstock Lode entered into decline that year, its fortunes would revive in

the early 1870s, when the Silver Kings struck the "Big Bonanza," the massive

veins of silver and gold buried deep beneath the windswept heights of Mount

Davidson. Financed in large by California capital, the mines not only produced

enormous quantities of high-grade ore but sparked volatile trading in silver

stocks on the San Francisco exchanges. Courtesy Huntington Library, San

Marino, Calif .

as the "Bonanza Firm"— John W. Mackay, James G. Fair, James C. Flood, and William S. O'Brien—formed a formal partnership and pooled their money for stock operations. The resulting growth in stock transactions fueled the formation of a new wave of mining corporations.[60] By 1873, they controlled five mining companies: Hale & Norcross, Gould & Curry, Consolidated Virginia, California, and Ken-tuck[61] The rival campaigns waged through the stock market produced a staggering volume of transactions, peaking in 1874 at more than $260 million, more than ten times the total production of gold and silver from the Comstock that year. Before the

fight to control the Comstock was over, Ralston was mined. Though Sharon and the Bank of California survived, the activities of the Bonanza Firm exacted a heavy toll on the broader economy.

Following the pattern adopted by the Bank Crowd, the Bonanza Firm not only purchased all major suppliers to their mines, they also established an "independent" mill, the Pacific Mill and Mining Company, a corporation that they wholly owned. Such arrangements were so common that, in a trial closely watched throughout the mining West, the Bonanza Firm successfully countered shareholders' complaints of fraud by pleading that the practice represented industry custom.[62]

By the end of the 1870s, the era of the fabulous Comstock was nearly at its end. The mines had been gutted. In 1877, even as the Bonanza Firms mines produced millions in gold and silver, the mining stock market collapsed, and California's economy sank into depression. The California Assembly Committee on Corporations concluded:

Where there should be universal prosperity and happiness, there is widespread poverty and suffering. Thousands of comfortable homes and many millions of dollars earned by the patient toil of the industrious masses, have been swept away by disastrous investments in mining shams. Undoubtedly the stock market has been a chief factor in producing the present destitution of the people. Its baneful effects have been felt in every neighborhood and almost every family in the State.[63]

Conclusion

Much of the scholarship on the rise of corporations during the nineteenth century has focused on elements of internal organization and competition within free and unregulated market arenas. Organizations are treated as distinct entities, independent from one another and dependent for survival on the efficient use of market resources.[64] My research into the rise of mining corporations and their interrelations across markets presents a very different view.

As mining corporations proliferated in California during the early 1850s, a new pattern of economic power emerged. Direct individual control over investment capital was displaced by indirect control and the loss of decision-making power, as the power of corporate insiders expanded. During the 1860s, the sudden wave of mining incorporations stimulated by the development of the Comstock Lode created the opportunity for insiders to manipulate information, along with legal and financial resources. In effect, these powerful actors used mining corporations as tools to advance their own plans and fortunes to the detriment of the underlying economy.

As mining advanced east and north from California, miners carried with them the techniques, practices, ideas, and organizing strategies—as well as the problems—

that emerged during the Gold Rush and were institutionalized during the era of the Comstock Lode in the 1860s and 1870s. Mining, which continues to be a risky undertaking, still carries the burden of its speculative past.