1. Persons and Families

1. Personhoods

| • | • | • |

Entering a Net of Maya in Mangaldihi

I arrived in Mangaldihi quite by chance. I had landed in India at the end of December 1988, anxious to begin research. I had thought I would focus on a rural community or village, where it might be easier for me to get to know a wider variety of people, since villagers would tend to be less enclosed than city dwellers within the walls of their own homes and workplaces. Several restless weeks slipped by in Calcutta and then in the sophisticated university town of Santiniketan while I sought suggestions about a specific location. To most of the Bengali city and town people I met, villages (grām) were distant, almost foreign places that elicited nostalgia.[1] Ancestral connections might lie there or the roots of one’s identity (Calcutta schoolchildren reportedly had to compose an annual essay on “My Village”). But many times I was told that I could not possibly live in one. I could perhaps visit a village on a bicycle, but if I were to live there—I would certainly get sick, perhaps even die, and definitely suffer. I finally met a few people who still had family or ancestral homes in villages that they visited regularly. One of these was Manik Banerji, who worked as a schoolteacher near Santiniketan and whose mother’s brother lived in a large village called Mangaldihi about thirty kilometers away.

The relationship with a mother’s brother (māmā) is a very special one for Bengalis, full of pampering and sweetness. One can ask one’s mother’s brother for almost anything, and he is expected to indulge the request. So when Manik Banerji wrote a letter of introduction for me to his mother’s brother in Mangaldihi asking this man to help me out in any way he could, Manik Banerji assured me (with a glint in his eye) that his māmā would surely oblige. He gave me directions to the village and house: a crowded bus ride to the town of Parui and then a long cycle rickshaw ride past rice fields and small villages to the sizable village of Mangaldihi, where I could not miss his uncle’s three-story brick home, the largest house in the village. And sure enough, the mother’s brother, Dulal Mukherjee, generously agreed to let me live in his compound, on the second floor of his family’s old and little-used mud house, above a dark and little-used doctor’s office, where my landlord kept a store of various medicines.

And so I was introduced to Mangaldihi, where I was to become caught up in what I would later learn to call the “net of maya,” or web of attachments, affections, jealousies, and love that in Bengalis’ eyes make up social relations. It began on my first night in Mangaldihi when a young woman from the neighborhood, Hena, came to sleep with me and be my companion. Or perhaps it began earlier that day, when I visited Mangaldihi briefly, accepted a glass of sugar water (śarbat) in Dulal Mukherjee’s home, and agreed to live in his neighborhood. Bengalis regard maya as being formed through the everyday activities of sharing food, touching, sleeping in the same bed, having sexual relations, exchanging words, and living in the same home, in the same neighborhood, or on the same village soil. These attachments link people (family, friends, neighbors), as well as people and the places, animals, and objects that make up their worlds. And once bonds of maya are formed, Bengalis often say, they are very difficult to loosen.

I learned this first through my relationship with Hena, the person with whom I developed the most intimate ties. My landlord and neighbors decided that I should have a companion to sleep with at night and to show me around, so they sent me an unmarried young woman in her early twenties from a poor Brahman family in the neighborhood. At once a younger sister and companion, she soon became a research assistant, a confidante, and a dear friend. After a few weeks went by, however, I decided that I needed to have at least a little time and space to myself (separation being valued by Americans), and I suggested to Hena that she let me sleep alone at night, that I needed the time to study and was not afraid of the village ghosts. Hena burst out weeping, “You’re trying to ‘cut’ (kāṭā) the maya! How will I live without you? I won’t be able to bear it.” So she remained my daily and nightly companion, as we cooked together and shared food, my single pillow, and confidences.

The people in the Mukherjee household and neighborhood also protested vehemently when, after about six months, I attempted to move into a larger, more comfortable home to prepare for my husband’s arrival. My neighbors and my landlord’s family would not have me moving into what was technically a different neighborhood, although the house was literally only a stone’s throw away: “How can you just cut the maya like that and move? You’ll become an ‘other person’ (parer lok).” And I was deluged with milk, fish, sweets, visits, and pleas to persuade me and strengthen our bonds, so that I could not leave.

From the very beginning of my stay in Mangaldihi up until the end, I heard a continual refrain—even after just one shared cup of tea, or a brief conversation on the roadside—“Oh, it is so sad that you have come, for you will have to leave again. How will we cut this maya when you leave? Maya cannot be cut.” And one day Sankar, a well-educated young Brahman man from Mangaldihi, sat down next to me on the bus as I was on my way to shop at the market in a nearby town and said: “There is one ‘tragedy’ [he used the English word] about your coming here. That is that you will have to leave. You must be hearing a lot about this. Bengalis hate separations. They feel so much maya for everything. You know maya? Once there is a relationship (samparka), they want to keep it strong (śakta). They want everyone to be together always.” People would also chide me, “You’ve just come here to cause maya to grow and then go away.”

Human relationships for Mangaldihians involved not only bonds of maya, attachment or affection, but also hiṃsā, jealousy. On one of my first expeditions to Mangaldihi I sat behind a Muslim rickshaw driver pedaling along the narrow paved road past fallow winter rice fields. As he gazed at the landscape he said to me, “Birbhum [the district Mangaldihi lies in] is the best place in the world. Everyone here knows each other and everyone loves each other.” His words made me feel exceedingly lucky to have happened on such a place: I looked around, with the winter sun warm on my face and arms, and admired the gentle hills undulating into the distance. Now his statement seems even more striking, because it was the only one of its kind that I heard. Much more frequently, I heard about and experienced the pervasive hiṃsā in the region’s villages. People would tell me, “Bengalis are a very jealous people (bāngālīrā khub hiṃsute jāt).” And the people of Mangaldihi thought that they were even more jealous than other Bengalis.

I certainly experienced jealousy in Mangaldihi, which seeped into almost everything I and other people did—as people (especially women) bickered and argued about who gave more tea, rice, sugar, snacks, money, fish, land, photos, saris (on loan), attention, and so on to whom; who was favored, who was not; who was loved most, who was not. I often wondered to myself, near despair, if they could be right about the general disposition of Mangaldihians; and if so, why had I chosen this village? But it takes a certain amount of intimacy to be involved in such struggles, and so I finally realized that the intense jealousies I often encountered were due in part to my privileged position. Being in some ways one of their own people (nijer lok), I was inevitably embroiled in the tangles (jaṭ) of jealousy and wants and givings and receivings and affection and love that Bengali relationships entail.

By the end of my stay in Mangaldihi, the people of the village had indeed finally begun to view me as one of them—for they worried less about their pain and tugs of maya than about mine. People would say with compassion, again and again over the weeks before my departure, “We have maya for only one person—you—who will leave and cause us pain. But how much more pain will you suffer! For you have maya for all of us, and will have to leave all of us.” They viewed me as in the center of a “net” (jāl) of maya, holding multiple strands that I had gathered during my eighteen months there—bonds of affection and attachment for all of the people of the village, and also for all of my things: the household items I had collected and lived with over a year and a half, my saris, my conch shell bangles (a sign of a married woman), my taste for Bengali food (how was I going to get by without eating ālu posta, potatoes with poppy seed paste, a regional favorite?), the village deities, the village land. How would I be able to cut the maya for all of these people, places, and objects and leave?

I came to view the ways people reacted to and interpreted my relatively brief and inconsequential stay in Mangaldihi as an avenue toward understanding how Bengalis think about and experience the forming and loosening of social-substantial relations in their own daily lives. Indeed, I found my coming and going to be particularly relevant for understanding practices and attitudes that surround aging and dying. For if the people I knew felt that it would be so exceedingly difficult for a person like me to leave Mangaldihi after residing there for only a number of months, what happens when a person who has lived for years and years with a family, in a village, on a piece of land, with all of his or her possessions, has to take leave of them all and die? Over and over again, this was a worry I heard expressed by older people, and by younger people contemplating their own future.

| • | • | • |

Open Persons and Substantial Exchanges

Such concerns about maya and aging—the forming and loosening of emotional relations over a lifetime—speak also to Bengali notions of what it is to be a person. A principal theme in sociocultural studies of South Asia over the past several decades has been the investigation of South Asian notions of what a “person” or “self” is.[2]

Several of these studies have focused on the fluid and open nature of persons in India. This insight was first voiced by McKim Marriott (1976), who with Ronald Inden (Marriott and Inden 1977) pointed to everyday Indian practices reflecting the assumption that persons have more or less open boundaries and may therefore affect one another’s natures through transactions of food, services, words, bodily substances, and the like. Marriott and Inden, who described the Indian social and cultural world as one of particulate “flowing substances,” suggested that Indians view persons in such a world as “composite” and hence “dividual” or divisible in nature. By contrast, Europeans and Americans view persons as relatively closed, contained and solid “ individuals” (see also Marriott 1990).

E. Valentine Daniel (1984) similarly emphasized that among Tamils, all things are constituted of fluid substances. In perpetual flux, these substances have an inherent capacity to separate and mix with other substances. Thus it is possible—indeed, inevitable—for persons to establish intersubstantial relationships with other people (sexual partners, household and village members) and with the places (land, village, houses) in and with which they live. Such substantial mixings point to what Daniel has called “the cultural reality of the nonindividual person.” They reveal the “fluidity of enclosures” in Tamil conceptual thought, whether those be the boundaries of a village, the walls of a house, or the skin of a person (1984:9, his italics).

Ronald Inden and Ralph Nicholas (1977) described similar personally transformative transactions among Bengalis, who to form kinship relations partly share and exchange their bodies by means of acts such as birth, marriage, sharing food, and living together (e.g., pp. 13, 17–18). Francis Zimmermann (1979, 1980) and Sudhir Kakar (1982:233–34), too, found notions of the fluid and substantially interpenetrative nature of persons, gods, places, and things in Ayurvedic texts and practices. Zimmermann in particular emphasized that the body in Ayurveda exists in a state of fluidity or snehatvā. The body is composed of a network of channels and fluids, which flow not only within the body but also among persons and their environments (Zimmermann 1979).

In Mangaldihi, I first encountered a notion of persons as relatively open and unbounded as manifest in what is called “mutual touching” (chõyāchũyi). The people I knew were concerned about whom and what they touched because touching involves a mutual transfer of substantial qualities from one person or thing to the next. Initially, I saw their concern most clearly in the management of “impurity” (aśuddhatā) in daily life.[3] High-caste Hindus avoided touching low-caste Hindus; Hindus avoided touching Muslims or tribal Santals; people of all castes frequently avoided touching those who were in states of “impurity” because of recent activities (e.g., defecating, visiting a hospital, or handling a dead body); persons about to make a ritual offering to a deity avoided touching any other person at all. To be sure, people often touched one another in the course of their daily affairs. But when they did, each considered that substantial properties from the other had permeated his or her own body, and the person who was in the “higher” or more “pure” position would often feel it necessary to bathe to rid him- or herself from the effects of the contact.

There are many forms of chõyāchũyi. Touching can take the form of simple bodily contact, as when a person touches another’s arm with her hand or brushes into another on a crowded bus. It also occurs when two people touch an object at the same time, such as when a person hands a pen or a photo or a cup of tea to someone else, or when two people sit on the same bench or mat at the same time. The objects in such cases conduct substantial qualities between the two people. Mangaldihi villagers told me that the only material that does not act as a conductor in this way is the earth (māṭi), including, as a kind of extension of the earth, the mud or cement floors of houses and courtyards. Thus, to avoid touching and the exchanges of substance that touching entails, people often refrained from handing objects to each other directly; instead, one placed an object on the ground for the other to pick up, or dropped an object into another’s outstretched hands. People themselves, like objects, act as conveyors or conductors of contact—so that two people who touch another person at the same time also touch each other. Furthermore, unlike objects, people generally retain the effects of touch: if someone touches one person and then (without bathing) another, this second person is considered to have been touched as well by the first.

It took many confused days and awkward experiences for me to learn about how touching was conceived as part of social interaction in Mangaldihi. People were constantly telling me that I had touched someone “low” (nicu) or “impure” (aśuddha) and therefore needed to bathe when I, with my definition of what constitutes touching, failed to see how I had touched anyone at all (and felt no need to bathe in any case). I have a particularly vivid memory of visiting Mangaldihi’s Muslim neighborhood for the first time, accompanied by my companion, Hena. On our way back to the Brahman neighborhood where we lived, Hena told me that we would both have to bathe. “Why?” I asked. “Because we touched Muslims.” “No we didn’t,” I protested, “We didn’t touch anyone while we were there.” “Yes we did,” she insisted, “We were sitting on the same mat with them, weren’t we.” “ That’s not touching!” I exclaimed. “Yes it is; of course it is!” “Well, we don’t consider that touching in my country,” I retorted. A little fed up after a long, hot day, and particularly disturbed by the implied prejudice that the act of bathing entailed, I let slip my usual anthropological stance of attempting to soak in information without challenge. “Well, here,” she said as she reached out and touched my upper arm, “ I touched them and now I touched you, so now you have touched them too, and you have to bathe.”

I also experienced, especially during my first few months in Mangaldihi, many people who avoided touching me—a non-Hindu and therefore in their eyes potentially very polluting indeed. I visited the home of an elderly Brahman widow several weeks after I had moved into the village in order to give her a photo that I had taken of her grandson. She stretched out her palms to receive it, in a gesture whose meaning would have been obvious to any villager: she did not want to be touched by me. She was requesting that I drop the photo into her open palms without making contact with her. But I only later understood the gesture; at the time, I naively placed the photo directly into her hands, thereby unwittingly contaminating the woman by my touch and making it necessary for her to go again to the pond to bathe.

Some forms of interpersonal exchanges have much more lasting and extensive effects than the relatively brief forms of bodily contact or touching described above, effects that cannot be removed simply by bathing. According to rural Bengalis, when a person cooks, for instance, his or her qualities and bodily substance permeate the cooked food and are therefore absorbed by those who eat it. People who eat the same food together at the same time and in the same location (as in persons served in the same row at a feast) also share substantial qualities with each other. It becomes obvious why people in most parts of India, including Mangaldihi, are so concerned about whose food and with whom they eat: in sharing food, they also share the substance, nature, and qualities of those who prepare, serve, and partake in it.

The people I knew viewed food leavings—food that had been touched with the saliva (lālā) of the eater—as also highly permeated with the eater’s substance. Leftovers, along with boiled rice, are considered to be ẽto, a term that refers specifically to food items that have become very highly permeated with the substances of those who have cooked, handled, and eaten them. People were very careful and selective about whose ẽto they would touch or ingest. Wives would eat their husbands’ ẽto (but often not vice versa), servants would eat their employers’ ẽto foods and wash their ẽto dishes (but definitely not vice versa), and close sisters or mothers and daughters would often share and trade ẽto food with each other.

The condition of being ẽto also spreads easily from a hand that has touched the mouth (either directly or via an object, such as a cup or eating utensil) to other persons and objects. When I drink a cup of tea, for instance, my mouth touches the tea cup, which touches my hand; and thus my hand becomes ẽto. If I wish to prevent the ẽto from spreading to other objects and persons, I must quickly wash it. I tried hard to regulate such practices, washing my hand after any eating or drinking, but in the eyes of my neighbors I was clearly not fastidious enough. They would tease me that my whole house and everything in it had become ẽto, that people concerned with purity and maintaining separateness from others (such as Brahman widows) should not even set foot into my home.

But a more serious breach in my conduct, a more reckless spreading of bodily substances, came much earlier, before people were comfortable enough with me to tease and criticize me about my ways—on my second visit to Mangaldihi, before I had moved to the village. Hena had taken me to her home, where she and her younger sister were eating their noon meal alone; their parents were away. Hena offered me a little bit of their rice and egg curry, and I accepted. When she stood up to clear away the dishes, I thought I would be helpful (in the American style) and I picked up my dish and placed it on the stack that she was holding. Without saying anything at the time, she went down to the pond to wash them. But when I returned to Mangaldihi the next day, she burst into tears and told me that several neighbors had seen her handle my ẽto dish and told her that they would not be able to touch her. I felt horrible for her. It was of course entirely my fault, for I had carelessly placed my dirty, saliva-covered dish in her hands without going to wash it myself (or at least leaving it on the ground, where she could have inconspicuously later called for a low-caste person to take it away). And her generosity and open-heartedness toward me had caused her to be slandered and ostracized by her neighbors. At the same time, I was also surprised by how uncomfortable, embarrassing, and even stingingly painful it felt to learn that other people found me literally untouchable.

After I left Mangaldihi that day I went to speak with Jamphul, an older Santal tribal woman who worked in my landlady’s home in the town of Santiniketan. She was at first indignant when I told her about the incident, saying “Why? Why didn’t you just ask them—’Am I poor like you?’”—an interesting response, revealing how she (like many in Mangaldihi) perceived real status and power to come from possession of money, which can in some ways even transform jāti or caste hierarchies. Then she added compassionately, “It makes you feel bad (khārāp), doesn’t it? It makes you feel ill at ease (aśānti).” She herself experienced untouchability all the time as a Santal, and like many lower-caste and Santal people in the region she found upper-caste concerns with rank ordering and impurity unjust and hurtful.

Marriott (1976), Daniel (1984), and others who have looked at such interactions have termed the properties that are felt to be transferred among people “substance,” translating an inclusive Sanskrit term (dravya) for something that is treated as material, though it is not necessarily visible. For want of a better word, I too sometimes use this broad term. But the Bengalis I knew did not use any specific equivalent word or phrase. When they discussed the effects of touching, it was simply clear that something was transferred between persons—that persons, after touching, shared something (parts of themselves, their qualities, their bodily substance) with each other. This transfer formed part of their taken-for-granted, commonsense world, and in our conversations about how touching works, what constitutes touching, and the effects of touching, they could not believe that I did not view touching in the same way. “Touching” (or chõyā) simply means a mutual contact that has a lasting effect on persons involved, so that the substance of each is changed by the other. Only the most insignificant kinds of touching (i.e., brief external bodily contacts) have effects that can be ended with bathing. Others, such as eating together, handling another’s ẽto, living in the same house, sexual intercourse, and marriage, have more permanent effects. They forge real bonds of relation—samparka, “relation,” “bodily connections”; or māyā, “attachment,” “affection”—among persons, who come to share something fundamental.

Ranking in general, particularly the ranking of jātis, or castes, has long been taken (particularly by European observers, as summarized by Dumont 1980a) as the most distinctive dimension of Indian society. Thus ethnographies such as those by Adrian Mayer (1960) and Marriott (1968), as well as analyses such as Marriott and Inden’s (1974, 1977), focused on asymmetrical transfers of food, water, and bodily substances (hair, saliva in food leavings, feces, menstrual blood, etc.) among castes. Louis Dumont (1980a) treated such transfers as reflecting an otherwise fixed vertical hierarchy of “pure” and “impure” castes, while Marriott (1968) and Marriott and Inden (1974) viewed transactions as continually creative of caste ranks. Marriott (1976) later analyzed intercaste transactions as also creating a second, horizontal dimension of “mixing” or alliance, and Gloria Raheja (1988) a third one of “auspiciousness” or centrality; but all earlier views of transactions had stressed only the differentiation of caste ranks.

I, too, initially found that the most striking and obvious dimension of the exchanges practiced by people in Mangaldihi pertained to jāti or caste hierarchy and particularly the managing of “impurity” (aśuddhatā) through avoidance. But as the days and months went by, I came to realize that an even more important and pervasive dimension of the open and unbound nature of persons in Mangaldihi had to do with seeking, cultivating, and intensifying mixings with kin, loved ones, friends, neighbors, things, and places. Hena was the first to seek such mixings with me. After I had been in Mangaldihi for several weeks, she began regularly to come over to my home to trade and mix some of her food with some of mine. Hena’s mother would often make ruṭi (flat bread) for me and I would cook rice for Hena. Then we would trade vegetables with each other and eat side by side. My landlord’s young daughter, Chaitali, would frequently do the same, rushing over after their family’s meal was prepared with a plate of rice and cooked vegetables to trade and mix with some of mine. And after two young sisters from the neighborhood became my cooks, they would eat all their meals with me and often rush to clear away my ẽto dish or wipe the place where I had been eating. I saw also how in their own homes, women in particular would trade rice and food, eat off others’ plates, finish one another’s ẽto leftovers, and eagerly call children to them to feed them food from their own plates with their own hands.

Parents, too, would clean away their children’s urine, excrement, and mucus without worrying about suffering any kind of bodily impurity. And as I will discuss in chapter 2, Bengalis defined the relations of children with their aged parents in important part by describing how children clean up parents’ urine and excrement lovingly and without complaint when they have become incontinent in old age and again after death.

Family and kinship ties in Mangaldihi (as throughout Bengal) were perceived as created and sustained through various kinds of bodily and other mixings, sharings, and exchanges (see also Inden and Nicholas 1977). People of the same “family” were said to “share the same body,” as sapiṇḍas: a word formed from piṇḍa, “body particle” or “ball of rice,” and sa, “shared” or “same.” Sapiṇḍas are people who share the same piṇḍas, or body particles, passed down from common ancestors, as well as people who offer together the same rice balls to the same ancestors. Families were also constituted by exchanging, sharing, and mixing via all sorts of other media, such as food (especially rice), houses, and blood (rakta). Mangaldihi villagers often referred to their families as those who “eat rice from the same pot” (eki hā̃rite khāi). They also called the members of their families gharer lok or “house’s people.” They spoke of the “pull of blood” (raktar ṭān) that they share with parents and siblings, and of the “pull” (ṭān) they have for their mother because they drank her breast milk (buker dudh) and were carried in her womb (nāṛī).

Thus social relations of kinship and friendship, as well as of jāti, relied on daily givings and receivings. I found that people in Mangaldihi built boundaries and avoided contact less often than they sought to become parts of each other—through sharing and exchanging their bodily substances, food, possessions, words, affections, and places of residence. This resonates with what Margaret Trawick writes of Tamil households, where mixing (kalattal,mayakkam) was viewed as a goal and pleasure in and of itself—one to be celebrated and renewed daily, and taught and learned as a value (1990b, esp. pp. 83–87). These kinds of exchanges result in what rural Bengalis often refer to as maya, the “net” (jāl) of bodily-emotional “ties” (bandhan), “pulls” (ṭān), or “connections” (samparka) that make up people and their lived-in worlds.

Such a vision of persons as open and partly constituted by what comes and goes also informed people’s conceptions of gender differences over the life course. Many spoke of women as being even more “open” (kholā) than men, especially during their married and reproductive years. This not only made women vulnerable to impurities or unwanted substances from outside (as were also the lower castes, several explained, comparing women to Sudras); it also gave women the highly valued capacities to receive a husband’s seed and produce a child; to mix with, nurture, and sustain a family (see chapter 6).

People in Mangaldihi likewise expressed the ambivalences and transitions of aging by referring to changes in the fluid and open nature of their bodies and personhoods. Aging was thought to involve simultaneous, contrary pulls in the kinds of ties that make up persons. On the one hand, these ties were felt to grow more numerous and intense as life goes on. On the other hand, aging was thought to involve the difficult work of taking apart the self or unraveling ties, in preparation for the many leave-takings of death (see chapter 4).

| • | • | • |

Studying Persons Cross-Culturally

Melford E. Spiro (1993) takes exception to the findings of several anthropologists, including notable South Asianists (Shweder, Bourne, Dumont, and Marriott),[4] who have suggested that while many non-Westerners de-emphasize individuality, Westerners view persons largely as bounded or autonomous individuals. Spiro’s article was stimulated by another article on the self by two social psychologists, expert on Japan (Markus and Kitayama 1991), who approvingly cite Clifford Geertz’s celebrated characterization of this Western conception as “a rather peculiar idea within the context of the world cultures” (Geertz 1983:59, qtd. in Spiro 1993:107).

According to Geertz, Westerners see the person as a “bounded, unique, more or less integrated motivational and cognitive universe, a dynamic center of awareness, emotion, judgment and action organized into a distinctive whole and set contrastively against other such wholes and against its social and natural background” (1983:59). If such a conception of the person as bounded is cross-culturally “peculiar,” then other (“non-Western”) people must view persons to be relatively not bounded. This premise—which is precisely what Geertz, and after him Hazel Markus and Shinobu Kitayama, does imply—is challenged by Spiro.

I will briefly take up Spiro’s key arguments here, because I believe that Bengali ethno-theories of persons can effectively resolve some of Spiro’s conundrums. Focusing his argument on the supposed bounded-unbounded (Western–non-Western) dichotomy, he begins by wondering what it could mean to be relatively unbounded as a person. Markus and Kitayama (1991:245) observe that in the case of many “non-Western” selves, “others are included within the boundaries of the self” (qtd. in Spiro 1993:108). Spiro responds, “This proposition…struck me as strange, because it seemed incomprehensible—what could it mean to say that others are included within the boundaries of myself?” (pp. 108–9).

The answer to this question rests in large part on what Spiro, Markus and Kitayama, and other scholars mean by the terms “self” or “person.” Spiro entertains briefly the notion that Markus and Kitayama could be referring to the self as the psychobiological organism, bounded by the skin. Such a self could be permeable to “others”—for example, microorganisms or germs that penetrate the body to cause disease, or spirits that possess an individual. However, such boundary crossings entail only impermanent and abnormal conditions, and Spiro therefore concludes that ethnographers who describe notions of unbounded selves could not be using the term “self” (or “person”) to denote the psychobiological organism. The more likely referent, he believes, is some psychological entity: an ego, a soul, or an “I.” But we still have a problem, Spiro insists, because all those who believe that others are included within the boundaries of their psychological self would have little, if any, “self-other differentiation.” That is, they would lack “the sense that one’s self, or one’s own person, is bounded, or separate from all other persons” (1993:110). Since all people must be able to differentiate themselves from others, they must think of themselves as bounded and separate from all other persons. This, he argues, is a “distinguishing feature of the very notion of human nature” (p. 110).[5]

These arguments give rise to several interesting questions. First, consider the self as a psychobiological organism. Clearly an unbounded psychobiological self might entail a broader range of possibilities than invading germs or possessing spirits. Even in the scant material from rural West Bengal that I have presented so far, it is evident that the Bengalis I knew viewed the sharing and exchanging of bodily and other substances—not only with other people but also with the places in which they live and the things that they own and use—as vital to the ways they think about and define themselves and social relations. Parts of other people, places, and things become part of one’s own body and person, just as parts of oneself enter into the bodies and thus the persons of others. Bengalis viewed such exchanges as neither abnormal nor temporary (though some are more or less desired, more or less lasting), but rather as an elemental part of everyday life and practice.

This does not mean that the Bengalis I knew could not differentiate themselves psychologically from others—they, like all people, perceptually perform self-other differentiation. But I see no reason for Spiro’s assumption that the ability to differentiate one’s consciousness from others is dependent on a notion of the self as “bounded, or separate from all other persons.” He conflates a sense of personal identity with that of personal boundaries: either people view themselves as perfectly bounded and separate, or they lose all capacity to differentiate themselves from others. One can, like the Bengalis I knew, have a clear sense of a differentiable self that includes bodily and emotional ties with others. Indeed, these ties make up the very stuff of who and what a (distinct and differentiable) person is.

Furthermore, Spiro’s added argument that Hindu and Buddhist theories of karma prove that there can be no “unbounded” Hindu or Buddhist selves seems equally misguided. As Spiro describes it, the Hindu and Buddhist theory of karma holds that every living person is the reincarnation of myriad past selves and that any person’s current and future incarnations are the karmic consequences of the actions of “his or her, and only his or her, own person” (1993:112–13, 1982). In short, he argues, “even if it were the case that other selves are included within the boundary of the Burmese [or any Buddhist or Hindu] conception of the self,…how then would we explain the fact that the Burmese explicitly affirm that no actor bears any responsibility for the action of others, even though the latter are allegedly included within the boundary of the actor’s own self?” (1993:113).

Here Spiro provides only one of the multiple theories of karma held by Hindu Indians, if not Burmese Buddhists. Several anthropological studies of different regions in India, as well as my Bengali informants, recount how karma may be shared among members of a family or community, making it not always simply an individual affair.[6] Susan Wadley and Bruce Derr (1990), for instance, tell of how a devastating fire in the north Indian village of Karimpur spurred a debate among villagers over the extent that karma is shared—the extent that the deeds of one person affect the lives of others. It became clear that “Karimpur residents viewed the fire as a community punishment, not merely an individual one” (p. 142).

The people I knew in West Bengal also offered theories of shared karma to explain a person’s or group’s misfortune. One respected Brahman priest and his wife were entering into old age with no children; the priest’s brother also had none. The family line (baṃśa) would be extinguished, and there would be no one to care for the two brothers and their wives in old age. The common village explanation was that they were suffering the karmic fruits of the misdeeds that their dishonest father had performed in his lifetime. As one woman told me, “When a father does sin, his sons have to eat the fruits.” Although Hindu South Asians also offer individual theories of karma to explain a single person’s own life circumstances, they frequently view karma as something that is shared by whole families or communities.[7]

This brings me to my next point, and here I agree with Spiro: dichotomies between Western and non-Western, individual and nonindividual, bounded and nonbounded conceptions of self or person should not be overdrawn (Spiro 1993:116). Thus, though the ethnographic literature on South Asia shows a long tradition of research holding that Indians (in various ways) de-emphasize individuality,[8] anthropologists have also examined ways in which South Asians view persons in terms that we might consider “individual.” [9]

Americans, too, may not always consider themselves to be as neatly bound, closed, and individual as many scholars have presumed. A study by Carol Nemeroff and Paul Rozin (1994), for instance, examines the so-called contagion concept among adult Philadelphians, the majority of whom, it turns out, believe that some kinds of essences (“vibes,” “cooties,” germs, moral qualities, etc.) are transferred from person to person through everyday exchanges such as sharing a sweater. Some feminist theorists have suggested further that models of the self emphasizing individual autonomy do not adequately describe the self-conceptions of American women, who are more likely than American men to focus more on connectedness to others. Multiple perspectives exist in any society or culture (e.g., Chodorow 1978; Gilligan 1982; Lykes 1985). What are often taken as the mutually exclusive values of “individuality” and “relatedness” may in fact interpenetrate within the same culture. And obviously persons steeped in South Asian culture live in the West and vice versa, making it even more difficult to draw any meaningful boundaries between “Western” and “non-Western” conceptions.

While I believe that it is possible to explore what people believe a “person” or “self” to be, I do not intend to investigate Bengali notions of personhood as a means of contrasting them to a putative generalized “Western” conception of the person. Rather, I use the rural Bengali material to examine views about personhood in a particular society, and then bring these views or ethno-theories into the arena of Western theoretical discussion about persons, selves, and genders.[10] More specifically, I explore how Bengali notions of persons as relatively open and composed of relationships (a notion I will continue to elaborate on) are tied to their perceptions about aging, dying, gender, and the forming and taking apart of social relations over the life course.

Notes

1. Dipesh Chakrabarty (1996) has written an elegant essay examining Hindu-Bengali nostalgia for “the village,” in the aftermath of the 1947 partition of West Bengal from East Bengal, when East Bengal became East Pakistan (in 1971, this same territory became Bangladesh).

2. On South Asian notions of person or self, see, e.g., E. V. Daniel 1984; Dumont 1980a; Ewing 1990, 1991; Lamb 1997b; Marriott 1976, 1990; Marriott and Inden 1977; McHugh 1989; M. Mines 1988, 1994; Ostor, Fruzzetti, and Barnett 1982; Parish 1994; Parry 1989; Roland 1988; and Shweder and Bourne 1984.

3. I write about “impurity” here at some length, partly because the topic has received so much attention in the anthropological literature on India and partly because it at first seemed to me so important to the local constitution of open persons and intersubstantial social relations. However, I gradually learned that social relations for Bengalis do not by any means center on avoiding impurity.

4. Spiro (1993) discusses these South Asianists particularly on pp. 115, 123–27, 132, where he concentrates on Shweder and Bourne’s (1984) notion of a “sociocentric” self.

5. Spiro supports his argument on self-other differentiation by drawing on James (1981 [1890]) and Hallowell (1955).

6. On shared karma, see Wadley and Derr 1990 and S. Daniel 1983:28–35.

7. For a detailed examination of how diverse theories of karma are used simultaneously by Tamil villagers, see S. Daniel 1983.

8. On de-emphasizing individuality in South Asia, see, e.g., Marriott 1976, 1990; E. V. Daniel 1984; Dumont 1980a:185, 231–39, and passim; and Shweder and Bourne 1984. Note that “individuality” is a polysemous term whose implications differ among these scholars.

9. For examples emphasizing the South Asian “individual,” see McHugh 1989; M. Mines 1988, 1994; M. Mines and Gourishankar 1990; and Parish 1994:127–29, 186–87. Marriott’s position is also more complex, variable, and nuanced than simply holding Hindu persons to be “unbounded.” Much of his work is devoted to what he sees as strenuous Hindu efforts toward closing boundaries (cooling oneself, minimizing interactions, “unmixing,” etc.).

10. Much of the confusion surrounding the cross-cultural study of personhood stems from a lack of specificity about what is meant by terms such as “person” and “self.” “Self” often implies what we might consider to be a psychological entity, such as an ego or a subjective experience of one’s own being. I therefore prefer to use the broader, more open term “person.” Beliefs about what it is to be a person in any cultural-historical setting might include notions and practices concerning some or all of the following: a subjective sense of self; a soul or spirit; the body; the mind; emotions; agency; gender or sex; race, ethnicity, or caste; relationships with other people, places, or things; a relationship with divinity; illness and well-being; power; karma or fate (perhaps ingrained in or written on the body or soul in some way); and the like. Our task as anthropologists studying personhood is to investigate what defines being a person, or being human, for the people we are striving to understand. For other discussions of what anthropologists mean by the terms “person” and “self,” see Harris 1989; Lindholm 1997; Pollock 1996; and Whittaker 1992.

2. Family Moral Systems

The most common Bengali term used to refer to what we in English might call a “family” is saṃsār. It literally means “that which flows together,” from the roots saṃ, “together, with,” and sṛ, “to flow, move.” In its most comprehensive sense, saṃsār refers to the whole material world (pṛthibī or jagat) and to the flux of births and deaths that all living beings and things go through together. More commonly, the term designates one’s own family or household (which is in some ways viewed as a microcosm of the wider world’s processes). Thus saṃsār not only refers to the people of a family or household, but also includes any household animals, such as cows, goats, or ducks; any family deities; the space of the house itself; and the material goods of a household—cooking utensils, bedding, wall hangings, and the like. All of this collectively makes up what Bengalis call their saṃsār, the assembly of people and things that “flow with” persons as they move through their lives. The SamsadBengali-English Dictionary, like some of my human informants, also lists “the bindings of maya” (māyābandhan) as one of the overlapping meanings of saṃsār—that is, the bodily and emotional attachments or “bindings” that connect people with the persons and things that make up their households and wider inhabited worlds. It was within saṃsārs, or families, in Mangaldihi that much of what constituted age and gender relations was played out. In this and the following chapter, I focus on people’s visions of the workings of families.

These visions entailed both consensus—what were often presented to me as shared “Bengali” values—and dissension or conflicting perspectives (for instance, between generations or genders). In today’s theoretical climate, it is often dissension or contestation that is highlighted (as I discussed in the introduction). Indeed, contestation—or the absolute heterogeneity of culture—has somehow become an overpowering trope, almost silencing what it was meant to allow for: that is, a heeding of the full range of diverse perspectives, visions, and experiences of those we are seeking to understand.[1] For it is not only anthropologists who have often (perhaps more often in the past) sought generalized or essentialized features of “cultures”; very often people essentialize themselves. For instance, those I knew in Mangaldihi commonly spoke to me of “Bengali culture,” or “Bengali people”—especially when describing to me (admittedly an outsider, for whom this kind of language might have been thought particularly appropriate) how families work and how aging is constituted within families. Scholars such as Partha Chatterjee (1993) and Pradip Kumar Bose (1995) have examined elite middle-class discourses on the family in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Bengal, in which the family was often presented as the inner domain of a national culture, a refuge from external colonial society. Such an awareness of cultural difference also underlay many Mangaldihi villagers’ discourses of Bengali family values (a point I discuss further in chapter 3). The workings of intergenerational family relations were presented as key parts of a Bengali local morality, a Bengali world.

The material in this chapter, as the label “family moral systems ” would suggest, concentrates on such discourses of a shared project. Some readers may be uncomfortable with the level of apparent agreement or systematicity they find. But I have stayed close to the visions and language of many of my informants; and if I had omitted this material, I would not have done justice to the ways they often wished to represent themselves. I will then turn in chapter 3, “Conflicting Generations,” to other, equally vital perspectives on age and gender relations within family life. Both chapters explore crucial components of the ways those I knew in Mangaldihi experienced and envisioned processes of aging, gender, and personhood within the arena of family life, an arena informed by specific politics and history.

| • | • | • |

Defining Age

When I began research in India, I did not decide in advance whom I would consider “old” (although my advisor in Calcutta, troubled by the lack of specificity in my research proposal, advised me to do so: “But whom will you be calling ‘old’ in your study? Will it be people above age fifty-five? or age sixty-five?”). Instead, I wished to find out how the people I lived with defined aging. Once in Mangaldihi, when I searched for ways to speak about what I would call “old age,” I necessarily had to begin by using Bengali words that approximated the topic. I asked what it is to be “grown” or “increased” (bṛiddha) or relatively “senior” or “advanced” (buṛo) in life and social importance.[2] I soon also heard the term bayas, referring to life’s “prime stage,” or an advanced “age” or “phase” of life.

I was virtually never told directly about age in absolute measures. Most people in Mangaldihi, in fact, did not know their age in years and placed little importance on such information. Although people of course sensed the repetitive cycles of seasons and celestial events as well as the accumulation of changes in their bodies, families, communities, and nation, few counted the particular number of years passed in their lives as markers of identity or of life stage, or kept track of and celebrated their birthdays.

Some of the more elite and literate families, especially among the Brahmans, did keep accounts of birth dates and such in record books, particularly so that they might cast horoscopes when arranging marriages. Some of those in Mangaldihi with salaried jobs also noted their seniority in years for bureaucratic purposes. But such knowledge was generally considered to be elite or technical information, a kind of “symbolic capital” (Bourdieu 1977:171–83) that demonstrated the possession of education, record books, salaried jobs, and the wealth that these goods entailed. One elderly Kora widow answered sharply when I asked her age, “How would I know that kind of thing? That’s a matter of paper and pencils. Where would we get things like that? Knowing your age (bayas) is for boṛo (‘big’ or ‘rich’) people like you or Brahmans.”

Much as Sylvia Vatuk (1990) had observed in Delhi, in Mangaldihi family criteria, and particularly the marriages of children, were held above all to constitute the beginnings of the senior phase (buṛo bayas). The family heads initiated their transition to being “senior” by gradually—often with years of ambivalence, arguing, and competition—handing over their duties of reproduction, cooking, and feeding to “junior” successors, usually sons and sons’ wives. When their children married, women would also start to wear white saris, which signified their increasing seniority and asexuality.[3] Since such successions and retirements might occur when members of the ascendant generation were of any age between about thirty-five and sixty, the Bengali senior stage corresponded roughly to the second halves of most villagers’ lives and to what today’s Americans might call “middle” and “old” age.

People defined aging physically as well, describing the old body as “weak” (durbal), “cool” (ṭhāṇḍā), “dry” (śukna), and sometimes “decrepit” (jārā). Lawrence Cohen (1998) scrutinizes the “hot” and “weak” minds of the senile whom he searched out amid the neighborhoods of Varanasi, but in Mangaldihi such changes in the mind—though noted at times—were not commonly stressed as constitutive of old age.

Well-educated Brahmans in Mangaldihi would also sometimes discuss aging in terms of the āśrama dharma schema: the idealized four-stage life cycle of the dharmaśāstras, the classical Hindu ethical-legal texts.[4] In this schema, men move through a series of four life stages or “shelters” (āśramas)—as a student, a married householder, a disengaged forest dweller (vānaprastha), and finally a wandering renouncer (sannyāsī).[5] When a man sees the sons of his sons and white hair on his head he knows it is time to enter the forest-dweller phase—departing from his home to live as a hermit, or remaining in the household but with a mind focused on God. The final life stage is conceptualized as a time of complete abnegation of the phenomenal world and its pleasures and ties. Some in Mangaldihi compared spiritually minded elders (especially Brahman men) to the forest dwellers or renunciants of the āśrama dharma schema, a comparison I scrutinize further in chapter 4.

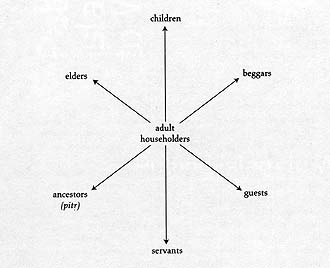

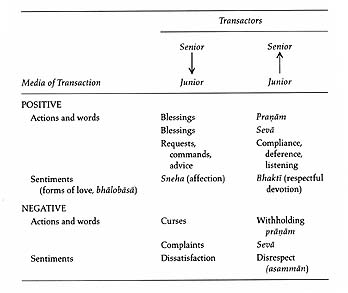

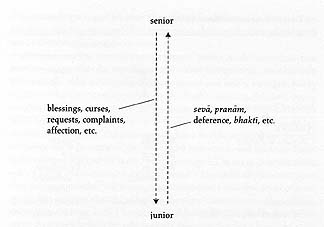

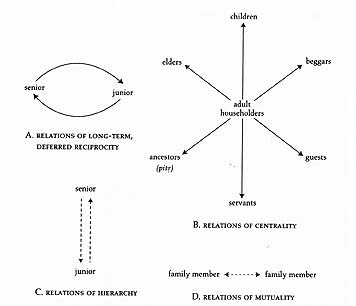

The people I knew in Mangaldihi often explained the workings, meanings of, and values behind the transitions of aging by referring to transactions—who gives what to whom, and when, and why. In the previous chapter, I described how substantial-emotional connections of maya were created between kin and close companions through sharing and exchanging substances, such as food, material goods, a house’s space, breast milk, body particles, words, and the like. But people did more than share goods with one another (a relationship I will call “mutuality,” following Raheja 1988, esp. p. 243). They also defined and created relatedness in terms of three other distinct modes of transacting, which I will call long-term (deferred) reciprocity (e.g., a parent provides food for a child, expecting the grown child to provide food for the parent years later in return), centrality and peripherality (e.g., an adult is positioned in the donative center of a household, distributing goods and services to peripheral children and elders), and hierarchy (seniors, the “increased” and “grown” folk, give out blessings and guidance to, and receive services and respect from, juniors and little ones).

Gloria Raheja (1988), in her analysis of the prestations or gifts given and received by people in the northern Indian village of Pahansu, has also found it useful to think of configurations of castes and kinsmen in Pahansu in a tripartite set of transactional dimensions—“mutuality,” “centrality,” and “hierarchy.” Her study focuses on the prestations that move between households of different castes and kinsmen. In this chapter and the next, I focus on the kinds of givings and receivings that went on within households in Mangaldihi. And though an important part of Raheja’s study of interhousehold prestations surrounds the dispersal of “inauspiciousness,” I encountered no similar transfers within Mangaldihi households. By examining household transactions, I shed light on the internal dynamics of families and on how relations of aging and gender were constituted, thought about, and valued.

| • | • | • |

Long-term Relations: Reciprocity and Indebtedness

People in Mangaldihi described Bengali family relations as entailing long-term bonds of reciprocal indebtedness extending throughout life and even after death; focusing on this transactional relationship provided one of their main ways of speaking about the connections binding the generations. Juniors provided care for their elderly parents, reconstructed relations with parents as ancestors after death, and ritually nourished these ancestors as a means of repaying the tremendous debts (ṛṇ) owed for producing and caring for them in infancy and childhood. According to my informants, this—the moral obligation to repay the vast debts incurred—was the primary reason adult children cared for their aged parents and nurtured their parents as ancestors after death.[6]

The process of producing and raising children was described by Mangaldihians as a series of givings. Parents give their newborn children a body, made up of their own blood—from the father’s seed or semen (śukra, a distilled form of blood) and the mother’s uterine blood (rakta,ārtab), which nourishes the fetus in the womb (garbha).[7] Parents then nourish their children with food: a mother’s breast milk (buker dudh), rice, and treats of sweets and fruit. They also provide their children with material necessities—clothing, bedding, money, and the like. They clean up their infants’ urine and feces. They are responsible for their children’s having the whole series of life or family cycle rituals (saṃskārs), from birth through marriage. And finally, through all of these givings, they endure tremendous suffering (kaṣṭa). In the end, after giving to and constructing their children, the parents have largely depleted their own resources and thus they advance to a “senior” (buṛo) life phase.

But this series of givings from adult parents to younger children is only one phase of a much longer story. According to Mangaldihians, by giving to and raising their children, parents create in their offspring a tremendous moral debt, or ṛṇ, that can never be entirely repaid. Yet children are obligated to strive as best they can to pay it off by returning in kind the gifts once given to them, principally by providing for their parents when they become old and by ritually nourishing their parents as ancestors after death. As Gurusaday Mukherjee, Khudi Thakrun’s eldest son, explained:

Looking after parents is the children’s (cheleder)[8] duty (kartabya). Sons pay back (śodh kare) the debt (ṛṇ) to their parents of childbirth and being raised by them. The mother and father suffer so much (khubi kaṣṭa kare) to raise their children. They can’t sleep; they wake up in the middle of the night. They clean up their children’s] bowel movements. They worry terribly when the children are sick. And the mother especially suffers (māyer beśi kaṣṭa hae). She carries the child in her womb for ten [lunar] months, and she raises him from the blood and milk from her breasts. So if you don’t care for your parents, then great sin (khubi pāp) and injustice (anyāe) happens.

Another Brahman man and family ritual priest serving Mangaldihi, Nimai Bhattcharj, provided a similar explanation:

Caring for parents is the children’s duty (kartabya); it is dharma. As parents raised their children, children will also care for their parents during their sick years, when they get old (bṛiddha). For example, if I am old and I have a bowel movement, my son will clean it and he won’t ask, “Why did you do it there?” This is what we did for him when he was young. When I am old and dying, who will take me to go pee and defecate? My children will have to do it.

Women also spoke to me of the long-term relations of reciprocal interdependence and indebtedness they had as daughters-in-law and mothers-in-law. As I will describe below, daughters largely cleared their debts toward their own parents when they married, inheriting at the same time new obligations toward their husbands’ parents. These new relations between daughters-in-law and parents-in-law were in part conceived of as reciprocal—for daughters-in-law were often married as young girls. This was especially true of the older women of Mangaldihi, whose marriages took place before child marriage regulations were implemented in India, when brides often were girls as young as eight, five, or even two. Many of these women described how they were cared for, raised, and nurtured by their mothers-in-law as new brides, sleeping with their mothers-in-law at night, and even—one woman told me—nursing from a mother-in-law’s breasts. Choto Ma explained the relations of reciprocal interdependence that she, as an older woman, now had with her daughters-in-law: “If our [daughters-in-law] didn’t care for us, then who would? At this age? We took these daughters-in-law in. And in our time, our mothers-in-law took us in and cared for us.…Now we are dependent on our sons and on our daughters-in-law. It has to be done this way.”

The attempt to pay back parents (or parents-in-law) the debts of birth and rearing does not end with care in old age, people said, but continues after death—as children suffer a period of death-separation impurity (aśauc) for their parents, perform funeral rites, reconstruct their parents as ancestors, and ritually nourish them. As Subal Gorai put it as he approached the end of the rigorous month of death-separation impurity for his deceased mother: “We must do the observances [of death-separation impurity] for our parents. In doing observances for our mother, we pay her back (śodh karā hae) for raising us. She suffered very much for us, so we will now suffer for her also.…But our suffering cannot equal hers. We are trying to pay [her] back but we cannot ever do it.” When villagers reasoned about such issues with me—about what children give to and owe their aged and deceased parents—I was struck by the near-identity of what parents once gave to their children and what children are later obligated to return. These reciprocated gifts included the gift of a body (after death), food, material necessities, the cleaning of urine and excrement, the final saṃskār or funeral rites, and the suffering and toil (kaṣṭa) that all of these acts of giving and supporting entailed (table 4).

| Phase 1: Initial giving (dāoyā) | Phase 2: Reciprocated giving, or the deferred repaying of debts (ṛṇ) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Medium of Transaction | Transactors, Senior → Junior | Medium of Transaction | Transactors, Junior→ Senior |

| Body | Parent → child | Body | Son (junior → parent of male line) (pret, pitṛ) |

| Food | Food | ||

| Breast milk | Mother → child | (Cow’s) milk | junior → elder, pret, pitṛ |

| Rice | Parent → child | Rice | junior → elder, pret, pitṛ |

| Treats (fruit, sweets, etc.) | Senior → junior | Treats | junior → elder, |

| Material goods | Material goods | ||

| Clothing, money, etc. | Parent → child | Clothing, money, etc. | junior → elder, pret |

| Services | Services | ||

| Clean up urine and excrement, daily care, etc. | Parent → child | Clean up urine and excrement, daily care, etc. | junior → Elder |

| Samskārs | Samskārs | ||

| First feeding of rice, marriage, etc. | Parent → child | Funeral rites | juniors → pret, pitṛ (of male line) |

KEY:

| |||

Some of these forms of reciprocal transaction have already been illustrated by villagers quoted above. For instance, villagers often described their own and others’ relations with aged parents by relating how they as adult children clean up the urine and excrement of their parents without complaining, just as their parents once tended to them when they were infants. As we have seen, Nimai Bhattcharj reasoned, “For example, if I am old and I have a bowel movement, my son will clean it and he won’t ask, ‘Why did you do it there?’ This is what we did for him when he was young.” Mangaldihi villagers frequently praised the way one Brahman man, Syam Thakur, cared for his very aged father with unfailing devotion until the day he died; Syam Thakur, I was told repeatedly, would himself take the excrement-covered sheets from his father’s bed to the pond to be washed, three or four times a day if necessary, never complaining and never (several remarked) tempted to feed his father less so that there would be less waste produced. Although not all old people become incontinent, dealing with a parent’s urine and feces was often held up as a paradigmatic component of the relation between an adult child and an elderly parent.

Moreover, people said, just as parents construct their children’s bodies by giving birth to them and nourishing them with food, so children (particularly sons) must provide new bodies for their parents after death. I will later explain in detail (chapter 5) the elaborate series of Hindu funeral rituals by which juniors construct new subtle, ancestral bodies for their deceased seniors, and then carefully nourish these bodies through ongoing ritual feedings. In fact, the ten-day (or sometimes longer) period of death-separation impurity that survivors endure when an elder dies was sometimes compared by villagers to the ten-month period of gestation during which an infant is produced in the womb (cf. Parry 1982:85). And several of my informants stated that by giving birth to their own children, they are also fulfilling a debt (ṛṇ) to their parents to produce children to carry on the family line, just as their parents had produced them.[9] By performing the last funeral rites for their parents, children also reciprocate the gift of a saṃskār to them. Parents construct their children by giving them the series of saṃskārs from birth through marriage, and in turn children give their parents the final saṃskār, the “last rites” (antyeṣṭi) and “faithful offerings” (śrāddha), after death.

Providing parents with food in late life and after death was regarded by villagers as perhaps the most fundamental of all filial obligations. People providing care for their parents in old age often spoke of “giving [them] rice” (bhāt dāoyā). They especially stressed the effort mothers expend in nourishing their children, feeding them milk from their own breasts, and the children’s obligation to reciprocate this nurturing. Subal Gorai said with emotion as he ministered to his mother during her last days, “[My mother] fed me with milk from her own breasts; how could I not feed her now?” If families could afford it, they often tried to provide their elders, as they do young children, special treats such as fruit and sweets made from milk. Villagers explained that as people grow older, their desire (lobh) for special kinds of food increases; if possible this desire should be indulged a bit. After a death occurred, too, junior survivors spent a great deal of effort feeding rice, water, and treats (milk, honey, yogurt, fruit, sweets) to the departed spirit and the ancestors.

Finally, villagers said that adult children have an obligation to provide their aged and deceased parents with the material goods needed to live comfortably. Living parents should receive clothing, a place to sleep, perhaps a little spending money, their medications, and the like; once deceased, in the funeral rites they receive clothing, shoes, a bed, eating utensils, an umbrella, money, and so forth. In this way, just as parents once provided their children with the substance of household life, the children years later reciprocate with these same kinds of goods.

All of these “gifts” to aged and deceased parents—performing the final saṃskār, constructing new bodies for them, cleaning them of urine and feces, feeding them, and providing them with material necessities—were spoken of as acts entailing considerable effort (jatna) and suffering (kaṣṭa). But no matter how much effort the children exert, I was told, they can never equal their parents in suffering and expense.

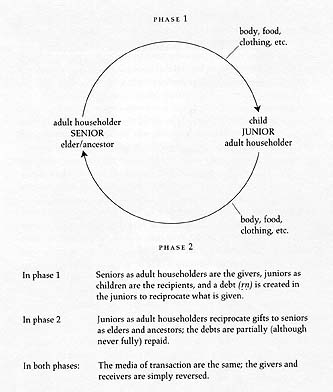

By engaging in this series of reciprocal transactions, people in Mangaldihi worked to construct long-term bonds of interdependence that connected people across the fluctuations of family life. Crucial to these reciprocations was the dimension of time. Those who engaged in a transaction (of food, a body, material goods) at one particular time (as a gift from parent to child) potentially gained something beyond that time—in future material returns and desired acts provided by their children much later, when they were old. Other anthropologists, such as Marcel Mauss (1967 [1925]) and Nancy Munn (1986), have looked at the kinds of transactions or gift exchanges practiced by people in various parts of the world that similarly aim to create debts in the receiver and thereby possibly win later benefits for the giver. In Mangaldihi, the dynamic applied within intergenerational transactions. The reciprocated transaction was deferred to a later family phase, when the parents had become old and the children were adult householders (figure 1). Thus, a major concern here was the durability of family relations over time, and not simply the equivalence of reciprocated exchanges.

Figure 1. Relations of long-term, deferred reciprocity.

This kind of thinking—investing now for future family phases and reciprocated returns—was explicit in villagers’ reasoning about why they provided care for their elders. At the same time that adult householders were providing for their elders, they were also raising their own children—and looking ahead to the time when they would be in the position of the elder receivers, and their own children would (they hoped) be doing the providing. As one woman told me: “If we don’t serve and respect our elders, then…my own sons and daughters-in-law will not serve me when I get old. If I don’t serve my śāśuṛī (mother-in-law) now, when I get old, my son will ask me, ‘Did you serve your śāśuṛī? Why should I serve you?’”

Such long-term reciprocal transactions also served in large part to maintain the “bindings” of a saṃsār, or family. A child may cry out in hunger, causing a “pull” (ṭān) in his mother—and the mother will give him or her a breast to nurse, or supply a plate of food. So an aging mother can also “pull” in hunger on the bindings that tie her to her child when her breasts are empty of milk in late life—and expect her grown child to provide food in return. These gifts of food, material goods, and bodies back and forth over several family phases and even in death played a major role in sustaining households and family lines, as well as the people who made them up.

Sylvia Vatuk (1990:66 and passim) also writes of relations of “long-term intergenerational reciprocity” within Indian families living near Delhi. She suggests that this conception of parent-child reciprocity as a “life-span relationship” sharply distinguishes Indian from American views of dependence in old age. Studies such as those by Margaret Clark (1972), Margaret Clark and Barbara Anderson (1967), and Maria Vesperi (1985) reveal that many Americans find the need to depend on younger relatives for support in old age destructive to their sense of self-esteem and value as a responsible person. They are distressed primarily because the relationship between an aged parent and younger caregiver is generally not perceived by these Americans—either the older person or the caregiver—as reciprocal, but rather as a one-way flow of benefits from the caretaker to the “dependent” (S. Vatuk 1990:65). Furthermore, most Americans expect the benefits in parent-child transactions to flow “down,” not “up” from children to parents. It is proper for parents to give to children (even, through gifts of money or inheritances, when their children are adults); but if an adult child gives to an aged parent, then the parent is seen as childlike. Vesperi studied growing old in a Florida city, where these old people “find themselves in life situations where they are defined a priori as dependent and child-like. They exist as supplicants, not as partners in reciprocal exchange. The supplicant is a shadowy form, an empty coffer; he or she receives but is not expected to give in return” (1985:71).

Of course, the degree of dependence in old age varies according to class and ethnicity; the problem is particularly acute for poorer people, who late in their lives have no accrued estate to draw from and potentially pass on to children. In Discipline and Punish (1979), Michel Foucault raises issues that pertain to this negative construction of dependence in old age. In a modern industrial society, he points out, people have been defined in terms of their ability to produce wealth and the means of their own subsistence; anything less is disciplined or despised.

As I will explore in greater depth in the following chapter, many people in and around Mangaldihi did indeed wonder and worry whether their children would feed them rice in old age; others lived in such poverty that they were unable to support aged family members, however much they might wish to; and still others were left with no children even to hope to depend on. Nonetheless, most continued to think of parent-child relations as long-term reciprocal ones, and those who knew something of the United States reflected on the care, or what they had heard to be the noncare, of the American elderly with horror. In Mangaldihi, even as many perceived faults and flaws in their relationships, the majority of “senior” people were cared for by sons and their wives in households crowded with cooking fires and descendants (table 5, page 54).

| Source of Support | Number of Seniors |

|---|---|

| Lived with sons and bous | 64 |

| Lived with daughter or other close relatives | 5 |

| Supported self through labor (maidservant, cow tender, maker of cow dung patties, etc.) | 17 |

| Supported self through independent income (property, savings, etc.) | 4 |

| Beggar | 3 |

| Total | 93 |

| NOTE: "Senior" here was defined as anyone whom my research assistant Dipu (who conducted most of the house-to-house village census) and the household members he spoke with considered to be "senior," "increased," or "old" (bṛiddha, buṛo). These were generally those whose children were all married, who had gray or graying hair, who wore mostly white, and so on. All those listed as selfsupporting lived adjacent to junior kin. | |

The Marriage of Daughters: Repaying Parental Debts with Mouse’s Earth

It was at the marriages of their children that parents instigated the new phase in which the direction of giving would be reversed and begin to flow from children to parents. Specific portions of the marriage rituals performed for both sons and daughters dealt with the issue of repaying debts to parents, though to quite different effect. Women and men in Mangaldihi told me how daughters, like sons, incur vast debts toward their parents by virtue of being produced and raised by them; but unlike a son, a daughter ritually clears away these debts when she marries by performing a ritual of “giving mouse’s earth” (ĩdurer māṭi dāoyā) as she leaves her father’s home for her father-in-law’s home. The morning after the nightlong marriage ceremonies have been performed at the bride’s father’s home, the bride, groom, and the bride’s mother perform a ritual of parting (bidāe), one of whose functions is to enable the departing daughter to “pay back” (śodh karā) her parents, and especially her mother, for the debts (ṛṇ) she has incurred growing up. The mother, daughter, and groom come together next to the vehicle that will carry the daughter and her husband away—usually a rented car (“taxi”) if the family is fairly wealthy, a cycle rickshaw or oxcart if poor. Neighbors and relatives crowd around to watch the poignant event, often with tears streaming.

The mother blesses the bride and groom, imbuing them with auspicious substances by first washing their feet with turmeric paste and milk, and then touching their feet with whole rice grains (dhān) and sacred grass (kuśa). Next she wipes their feet with her unbound hair. Villagers explained that by this act a mother maintains connections with her daughter, even as she sends her away. Hair, especially in its unbound or “open” (kholā) condition (i.e., not braided or tied up in a knot), is thought to have properties very conducive to mixing or connecting. A mother also wipes the navel of her newborn child with unbound hair after the umbilical cord has been cut, to mitigate the separative effects of severing this physical bond. So, villagers explained, a mother wipes her departing daughter with her unbound hair to keep the mother and daughter “one” (ek). If she were to wipe her daughter’s feet (or her newborn child’s navel) with her hand, which is colder and more contained, the child would become “other” (par).[10] Finally, the mother wipes dry the feet of the bride and groom with a cotton towel, or gāmchā.

The critical point of the ritual comes next: the bride’s mother stands, opens the blouse under her sari, and has her daughter gesture toward nursing at her breast. Up until now, villagers explained, the mother has nurtured her daughter, and she offers her daughter her breast for the last time, before she turns her over to be fed and supported by her husband and his family. The daughter then takes from a handkerchief a handful of earth dug from a mouse hole (ĩdurer māṭi, “the earth of a mouse”) and places it into a fold in her mother’s sari; she repeats the act three times, as her mother hands the earth back to her. With each offering, the daughter repeats, “Ma, all that I have eaten from you for so many days, I pay back today with this mouse’s earth” (Mā, eto din tomār jā kheyechilām, āj ei ĩdurer māṭi diye tā śodh karlām). Mother and daughter usually weep as they perform this final act. The mother hands the bride a brass tray or cup filled with rice and sweets that the bride is to give to her mother-in-law when she arrives at her new home. The mother then turns away in tears and usually does not watch her daughter depart.

I heard several theories on the ritual significance of mouse’s earth. Some thought that because mice live in the house and eat rice grains, the staple food of a household, they are in some ways like the goddess Laksmi, the goddess of wealth and prosperity who is associated with rice. Mouse’s earth can therefore be regarded as a form of wealth, like rice, and can be given to a mother in compensation for her considerable expenditures. Alternatively, Lina Fruzzetti (1982:55–56), who describes a similar ritual among other Bengali women, suggests that the earth of a mouse represents the life of a married woman, who shifts wealth from house to house as the mouse shifts earth. The explanation that seemed most convincing to me, however, derived from the ritual’s triviality. Several village women told me emphatically that of course a daughter’s debts to her parents can never be truly repaid. That is why the daughter gives such a worthless item to her mother before she leaves, making it plain that she has not matched the value of the debt. One mother of four as yet unmarried daughters said to me, “Can the debt [to one’s parents] be paid back with the earth of a mouse? No! That debt will not be repaid.”

Nonetheless, because she had gone through the ritual motions of paying back her mother with mouse’s earth, a married daughter’s debts toward her parents were regarded as formally erased. With the clearing of this debt, the bride also weakened her bonds with her parents, for indebtedness entails a connection between two parties. Not understanding the positive local function of indebtedness, I unwittingly insulted several neighborhood women early on in my stay in Mangaldihi by attempting to pay off debts, returning a borrowed cup of sugar, or paying a few rupees in exchange for having a sari’s hem sewn. They would say to me, hurt, “What are you trying to do? Pay back [the debt] and cut off all ties?” For this reason, many mothers told me that they found the ritual of being paid back by their daughters almost impossible to endure. “To hear a daughter say, ‘I have paid off my debts to you’ (tomār ṛṇ śodh karlām),” one woman said, “gives so much pain.” Some mused that they would try to find others to perform the ritual in their stead, a husband’s brother’s wife or the like, but I never saw this happen.

By clearing her parental debts and moving on to her husband’s and father-in-law’s home, a daughter thus removes herself from the cycle of long-term reciprocal transactions that tie her natal family together. A daughter receives from her parents for years but repays these debts in a ritual instant only, which ends her most vital transactions with them. On rare occasions, especially if there were no sons in the family, a daughter would support her aged parents (see table 5); but doing so was not regarded as her obligation (dāyitva). Married daughters also usually continued to visit their natal homes, several times a year and even for weeks at a time, especially over the first few years of marriage. On such visits, they often secretly gave their mothers gifts of money, sari blouses, petticoats, and the like, especially if their husbands’ households were better off than their parents’. However, people believed that it did not look good if a married daughter gave too much to her natal parents. Married daughters are transformed from nijer lok, “own people,” to kuṭumbs, relatives by marriage,[11] and thus no longer rightfully had the role of looking after and providing for their parents.