The Bishop of Barcelona and the Nun from Zaragoza

Manuel Irurita paid close attention to Ezkioga in part because he was from nearby Navarra and returned every summer to the Valle de Baztán. But perhaps more important was that he, like Antonio Amundarain, had a taste for the marvelous. He was born just over the border from France, and of all bishops up to the Civil War, he was the one who went to Lourdes most frequently.[2]

Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 151. For Irunta's election as bishop of Lleida in 1926, Cárcel Ortí, "Iglesia y estado," 236.

Irurita was not shy about recounting a strange experience of his own. In 1927, when he was a canon in Valencia, he took the wrong train, an express instead of a local, on his way to preach at a Carmelite convent. He prayed for help to Thérèse de Lisieux, and the train jerked to a halt at the station for the convent. When he got off, he asked the engineer what had happened. The engineer said he had seen a nun standing on the tracks. None of the people on the platform had seen her.[3]

Ricart, Un Obispo, 40-41. In Valencia Irurita had been a member of the devotional Escuela de Cristo along with the bishop of Segorbe, who I think was sympathetic to the Ezkioga visions. F. Sánchez Castañer, "Escuelas de Cristo," DHEE 5:254.

Incognito, dressed as a layman, Irurita visited Ezkioga at least four times in 1931. He made his first visit with the priest from Alegia, Pío Montoya, and this may have been around July 21, when Irurita was in Navarra on vacation. His visit on July 31, in the company of Antonio Amundarain, was his third. By then he had had occasion to speak with one of six seers from his native Baztán who had traveled together to Ezkioga; he was impressed with the seer.[4]

N., "Anduaga-mendiko agerpenak [The Apparitions of Mount Anduaga]." Amundarain told the Catalans about the Baztán seer on 14 December 1931 (Gratacós, "Lo de Esquioga," 15-16); a bus from the Baztán valley went to Ezkioga on July 21: PV, 22 July.

In the aftermath of Ramona Olazábal's wounding Irurita returned to Ezkioga. We see him in photographs kneeling next to Ramona.[5]

The photo in my text, without a caption identifying Irurita, appeared in Antigüedad, Nuevo Mundo, 21 October 1931, and El Nervión, 22 October 1931.

Irurita's last visit to Ezkioga was an open secret and helped to maintain the respectability of the visions at a time when the diocese of Vitoria was turning against them. Pilgrims could buy a souvenir postcard showing Ramona, the Virgin, and Irurita. Irurita subsequently delegated a layman from Barcelona to observe the Ezkioga visions and report back to him. The Barcelona diocesan censor approved articles in favor of the visions for Catholic newspapers as late as the summer of 1932, and at the end of that year Irurita was still saying in private that he believed in the visions.Irurita's prior entanglement in the spurious prophecies of Madre Rafols deepened his interest in Ezkioga. For some time the Sisters of Charity of Saint Anne had been campaigning to canonize their founder, María Rafols y Bruna. The pseudo-Rafols story is a fascinating example of religious politics and merits study.

Rafols was born in 1781 near Vilafranca del Penedès in the province of Barcelona.[6]

For the historic Rafols see Tellechea Idígoras, "Rafols Bruna, Marie," DS 13 (1988), cols. 36-38.

She founded her order in Zaragoza, but it remained small until 1894, when Pabla Bescós became the superior. Bescós obtained approval for the order from Rome and before her death in 1929 organized over sixty new houses, some

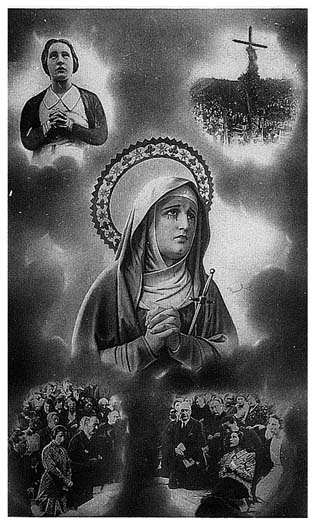

Manuel Irurita, bishop of Barcelona, in civilian clothes watches Ramona Olazábal in vision, 19

or 20 October 1931. Photo by J. Juanes. Courtesy Arxiu Salvador Cardús i Florensa, Terrassa

in South America. In 1932 there were 2,500 religious in 130 houses. As the order grew, its leaders moved to honor their founder. Bescós held meetings in homage to Madre Rafols in Zaragoza and Vilafranca, commissioned a biography, and began gathering documents.[7]

Manuel Graña, "La Madre Rafols," El Debate, 24 May 1932, p. 8; Vida de Pabla Bescós.

In the 1920s Madre Bescós's niece, María Naya Bescós, was a teacher of novices. Perhaps out of a sense of proprietary connection with the order and its history, she began to falsify documents to fill in and illustrate the life of the founder. She made her forgeries with care, using period paper. Her procedure was to observe or provoke contemporary events and have the Sacred Heart of Jesus predict them to Madre Rafols a century earlier. Then she would "discover" the prophecies. For instance, when Naya and the acting superior Felisa Guerri went to purchase the Rafols homestead on 31 August 1924, Naya pointed to a crucifix and identified it as belonging to Madre Rafols. Supposedly the crucifix was fixed to the wall, but Naya was able to remove it with ease, as if she herself had some supernatural power. Later she doctored a prophecy (and discovered it on 2 January 1931) to confirm that the crucifix belonged to Madre Rafols and to

Souvenir postcard of apparitions at

Ezkioga: The Sorrowing Mary, Ramona

Olazábal, and Manuel Irurita, bishop of

Barcelona, October 1931. Photo by J. Juanes.

consecrate its removal as miraculous. This crucifix—El Santo Cristo de la Pureza y Desconsuelo—became an important relic.

María Naya "found" forged letters and spiritual writings in 1922 and between 1926 and 1932. She confirmed her own special role in 1930 by putting into a message from Jesus that the documents would be discovered by "one of [Rafols's] daughters much beloved by my Heart." The prophecies implied that the church would canonize her aunt Pabla as well. On 15 November 1929 workers digging the foundations for a convent at the Rafols homestead found a

second crucifix, allegedly with fresh blood on it. In January 1931 Naya located a prophecy about this crucifix—El Santo Cristo Desamparado—and in October 1931 another about its discovery.

Irurita was named bishop of Barcelona in March 1930 and Vilafranca del Penedès fell within his diocese. On 30 April 1931 he laid the cornerstone for the complex of buildings at Vilafranca. From September 14 through 16 he displayed in his episcopal chapel the crucifix that had "bled" as public atonement for Spain's sins. For long periods he himself held the image for the faithful to kiss. This provoked scenes of religious enthusiasm unusual in Barcelona under the Second Republic. Barcelona Catholic newspapers printed the tales of the miraculous discovery of the crucifixes, and a Barcelona cathedral canon put out a pamphlet. A Zaragoza manufacturer sold copies of El Cristo Desamparado nationwide. Of course, these were trying times for Catholicism and Irurita was acutely aware that the church was no longer one of the powers in control of the nation. In this context a bleeding crucifix meant something special, as did the appearance of the Sorrowing Mother in the Basque hills.[8]

"La Venerable Mare María Rafols," EM, 16 September 1931, p. 2; "La imatge del Crist Desemparat exposada a la Capella de Palau Episcopal," EM, 15, 16, and 17 September 1931, p. 2; and "La imagen del Cristo Desamparado; Piedad consoladora," CC, 17 September 1931, p. 1. Cardinal Pedro Segura dedicated the Vilafranca shrine with three days of prayer in late October 1941, and Esteban Bilbao, minister of justice, said that Irurita had told him about the revelations personally (La Vanguardia Española, 28 October 1941, p. 5). Bilbao said that during his captivity in the Civil War the Rafols prophecies, which presaged "the victory of the sword of Franco," always comforted him. Pamphlet by Barcelona canon is Boada y Camps, Los Crucifijos.

A canon of Zaragoza, Santiago Guallar Poza, was in charge of the Rafols cause. The diocesan tribunal, the first stage in the beatification process, began in July 1926 and finished in February 1927. In 1931 Guallar published a biography of Rafols with the materials he had gathered. That year he was one of eight priests elected to the Constituent Cortes in Madrid. I do not know whether Guallar was aware of the forgeries. But in 1931 politics was on everyone's mind, and Naya began to compose prophecies with a political slant. On 2 October 1931, when the Cortes was about to discuss separating church and state, Naya uncovered a text that included a vision by Rafols of the Sacred Heart predicting visible miracles. And on 29 January 1932, the day the government dissolved the Jesuit order in Spain, Naya found a political prophecy that foretold a chastisement and explained that sacrilege, the removal of the crucifixes, and the expulsion of the Jesuits was the work of the Masons and God's punishment of Spain for female indecency.

The Vatican checked these more political texts and permitted their publication (although the names of the cities God would chastise and the names of living persons were excised). The last prophecy caused a special stir, and Pius XI gave Felisa Guerri and María Naya a second audience. They had already visited him in February 1931 to show the crucifixes. The political prophecies gave the Rafols cult an enormously expanded audience. The texts, in booklets introduced by the Navarrese Jesuit Demetrio Zurbitu, went out by the tens of thousands in early 1932. What started as a pious fraud to make a saint turned into a rally to toughen Spanish Catholics against the secular Second Republic.[9]

The Roman nihil obstats are 1 December 1931 and 27 April 1932. Demetrio Zurbitu (b. Betelu 1886-d. Barcelona 1936) had been director of Marian Congregations in Barcelona: Mècle, "Deux victimes," 6 (I thank Jacques Mècle for letting me consult this unpublished paper). Arrese, Profecías; also López Galuá, Futura grandeza, first ed., 1939.

A commission of experts appointed by the diocese of Zaragoza decided unanimously in January 1934 that the documents were forgeries, but their

finding, since it was part of the beatification process, was kept secret. Clergy who openly questioned the documents included the French Benedictine Aimé Lambert; the preacher Francisco de Paula Vallet; the Dominican Luis Urbano, even more scornful of the Ezkioga visions that he had been of those of Limpias and Piedramillera; and the liturgical scholar Josep Tarré. In the Basque Country Canon Antonio Pildain spoke against the revelations in the cathedral of Vitoria in 1933, and in 1941 Manuel Lecuona, a Basque folklorist from Oiartzun and a former professor at the seminary in Vitoria, published proof of plagiarism.[10]

There was an article ridiculing the Rafols prophecies in EM by P.D., 8 July 1932. Lambert's critical "Los 'escritos póstumos'" was also published in El Bon Pastor, April 1933. I do not know if Eugenio Ferrer published "Los escritos," his rebuttal of Lambert. For Pildain: Juan Bautista Ayerbe to Alfredo Renshaw, 6 October 1933, ASC. Manuel Lecuona, in hiding in a convent of Brígidas in Lasarte, found a source for the forgeries and wrote "Escritos de la M. Rafols." He had been suspicious of their pro-Spanish slant. The Dominican Luis Urbano wrote "Neumann, Rafols" and published Josep Tarré's "Crítica interna." According to Lecuona (Oiartzun, 29 March 1983), Tarré wrote an exposé in several volumes but could not publish it. Francisco de Paula Vallet alerted his friend Josep Pou i Martí in Rome against the prophecies in the summer of 1932. Cardinal Pedro Segura was a prime defender of the prophecies; others included Olegario Corral, Autenticidad, first in Sal Terrae, January 1933, and Castor Montoto, En los escritos. The Zaragoza panel (Mècle, "Deux victimes," 8) consisted of Lambert, the Jesuit scholar Zacarías García Villada, and the director of the Archivo Nacional, Miguel Gómez del Campillo, who later participated in the inauguration of the Vilafranca complex.

After the case reached Rome, in 1943 another panel of experts, including the Catalan Franciscan Josep Pou i Martí, was also unanimously negative. They based their finding on anachronisms, the use of metal pens, the use of the same batch of paper over what was ostensibly a span of forty years, the handwriting, and the outright copying of contemporary literature. The Vatican closed the case, but discreetly, never informing the general public of the fraud. María Naya lost her position with the novices and the order had to withdraw the crucifixes from veneration. But people still read the old books and pamphlets, as well as an occasional new book. Naya, who died in 1966, never spoke on the subject, never admitted her role, and never revealed who, if anyone, worked with her.[11]

Mècle, "Deux victimes," 13, cites Caesaraugustan: Beatificationis ac canonizationis Servae Dei Maria Rafols: Inquisitio super dubio an constat de autenticitate scriptorum (Roma: Polyglotte Vaticane, 1943). For a more recent work see Becker, Tiempo profético.

María Naya hoodwinked Irurita into the Rafols deception by flattery and co-optation, just as she hoodwinked certain Jesuits and even Pius XI. In the message she found 2 January 1931, the last before the messages turned political, Naya had Jesus tell Rafols that "a holy prelate very zealous in the salvation of souls and devoted to his Divine Heart would help my Sisters with his advice and with the other means that [Jesus] would provide him in order to put into practice all the plans of his Divine Heart."[12]

Naya had the Sacred Heart say he wanted the Jesuits to be in charge of all the seminaries in Spain and Pius XI to establish the Feast of Christ the King in the Church Universal (Zurbitu, Escritos, 59-60). Quote from "La Venerable Mare María Rafols," EM, 16 September 1931, p. 2.

Irurita's support was important for the beatification, for Rafols had been born in his diocese. His support was also essential for the new convent and shrine at the homestead site. His personal promotion of the Rafols shrine and the crucifixes demonstrated his total identification with the prelate in the prophecy. Later, to erase any doubt, Naya inserted in the message of 2 October 1931 a reference to the "Lord Bishop who in those years [1931–1940] governs this diocese of Barcelona."[13]Zurbitu, Escritos, 24, message found 2 October 1931.

The belief that he had a providential role to play in Spain's dramatic days sharpened Irurita's interest in the Ezkioga visions. He quickly noticed the convergence of the Basque vision messages and the Rafols prophecies. In the fall of 1931 both predicted visible public supernatural events and by that time both emphasized not Euskadi but Spain. In the Rafols message of 2 October 1931, when the Ezkioga multitudes expected miracles, the Sacred Heart of Jesus said he would, if he had to, save Spain from the devil. He would do so, he said, "with the help of portentous miracles that many people will see with their own eyes; and my Most Holy Mother will communicate to them what they must do to

placate and make amends to my eternal Father." A Catalan correspondent wrote to Ramona about Irurita's attitude toward this vision:

I know that some time ago our Bishop warned your Vicar General to act very carefully since the revelations of the Sacred Heart to M. Rafols ultimately support the cause of Ezquioga. I do not know how he took it. Do not speak of this as it is a sensitive matter.[14]

The Gipuzkoan priest Pío Montoya, who accompanied Irurita to the vision site, remembered that Irurita was at the time seduced by the Rafols prophecies and emphasized their Spanish aspect (San Sebastián, 7 April 1983, p. 16). Quotes from Zurbitu, Escritos, 37, and Cardús to Ramona, 9 March 1932, enclosing Rafols booklets.

The Rafols document of January 1932 warned of a chastisement of Spain which would precede a new age.

This writing will be found when the hour of my Reign in Spain approaches; but before that I will see that it is purified of all of its filth…. [M]y Eternal father will be forced, if they do not reform after this merciful warning, to destroy entire cities.[15]

Zurbitu, Escritos, 56.

Since October 1931 Ezkioga seers had been speaking about chastisements on a grand scale, including the destruction of three Spanish cities. The new Rafols revelation also pointed to a solution—prayer with arms in the form of a cross—that had been in use daily at Ezkioga for seven months by the time Naya produced the message: "The most powerful weapon to win the victory will be the reform of customs and public prayer. The faithful should gather and do petitionary processions and other devotions with their arms in the form of a cross." The Terrassa writer Salvador Cardús noted this similarity immediately and attempted in vain to point it out in the press.[16]

Zurbitu, Escritos, 68; Cardús wrote an article relating Ezkioga and Rafols, "Els fets," by 27 May 1932; both El Matí and Revista Franciscana of Vic rejected the article.

The convergence was not casual. By the time of the last two forgeries, María Naya was clearly aware of what the Ezkioga seers were saying. She and others in the order would have heard from Irurita himself about the visions. And groups of Catalan pilgrims stopped to see her on their way to Ezkioga. One of the group leaders recounted a visit to Zaragoza as follows:

Hermana Naya explained to us the details of her wonderful finds and how she would hear an interior voice that told her to pick up a certain key [to a cabinet or closet], and where and which ones were the writings she was looking for. And then, without our asking her, she expressed her conviction that the Ezkioga matter was certain, that an interior voice affirmed it, although she added prudently that there might exist a small proportion of exaggeration or fiction. And to a question by D. Luis Palà she answered that the interior voice that affirmed to her the reality of the Ezkioga matter was the same, exactly the same, as that which made her pick up a key and find the writings of Madre María Rafols.

In 1932 Naya produced yet another document that confirmed the Ezkioga visions more explicitly. On June 25 she told Ezkioga seers who visited her of a great new revelation, still secret. And on July 12 an Ezkioga enthusiast knew from a Jesuit

friend that "in Rome there is another document of Madre Rafols and that this one is even clearer about Ezquioga. It seems that it will not be made public because it specifies many things and even events of great importance." While these visits and those of high churchmen to Hermana Naya were no doubt in good faith, they bring to mind Leonardo Sciascia's tale Il Consiglio d'Egitto , in which a Sicilian monk lets it be known he has discovered a manuscript of a Moslem history of Sicily and the nobles of the land pay him court and give him presents, hoping to get their families and landholdings mentioned.[17]

Long quote, Bordas Flaquer, La Verdad, 37; for Naya see Boué, 60, 78-79; for Rome see Cardús to Paulí Subirà, Terrassa, 12 July 1932.

Naya and the pseudo-Rafols prophecies in return influenced the Ezkioga visions. When pictures of Rafols began to appear in the souvenir stands at the bottom of the hill, seers began to recognize her. On 1 October 1931 Benita Aguirre had a vision of a nun and later, when given a picture by a Catalan believer, claimed to recognize the nun as Rafols. The visionaries saw Madre Rafols particularly in the spring of 1932, when they were reading booklets and articles about the prophecies.[18]

ARB 104-105; on 25 February 1932 Cardús sent Ramona excerpts from the Rafols October 1931 message and soon after he sent the full message. Ramona replied on March 10: "When I saw these beautiful booklets I showed them to my confessor and he said that everything in them is related to my [vision] declarations." Ramona was reading the Rafols biography by Guallar when she saw Cardús a week later. On May 10 he sent her excerpts from the new, final prophecy and ten days later several copies of the complete text for her and her confessor. Ramona had passed the brochure to Garmendia by June 6, when she wrote Cardús asking for more pictures of Rafols as "everyone wants one." Visions of Rafols in early 1932 included those by Micaela Goicoechea, April 17 (SCD 76-77); Evarista Galdós, April 29 (Rafols reading letter with date of chastisement, B 719); José Garmendia, May 1 (Virgin confirms congruence of revelations and Ezkioga visions, says more documents will appear and that Rafols knew a chapel would be built and the seers persecuted for it, B 634); a Catalan pilgrim, Antonia Quiñonero, in May (ARB 102); and Benita Aguirre, sometime before June 2 (SC D 112). At that time G.-L. Boué was writing both about Rafols and Ezkioga.

In early 1932 the Ezkioga seers had another source of news of the Rafols prophecies, this one close at hand. A priest using the pseudonym Bartolomé de Andueza had written an article about Rafols for La Constancia in 1925. Starting in late February 1932 and ending in late June 1932 he published a series entitled "The Stupendous Prophecies of Madre María Rafols." Andueza seems to have known Irurita. He reported that the bishop had given a woman dying with tuberculosis a picture of Madre Rafols; when the picture touched the woman, it cured her. Referring to the prelate in the Rafols prophecy, Andueza wrote, "Both to you and to me, there comes to mind the very fervent Dr. Irurita, the present bishop of Barcelona."[19]

Andueza, "Luz de lo Alto" and "Las estupendas profecías"; LC, 10 April 1932, p. 1. El Debate made the connection on 23 April 1932: "Se dice que ... prueban algunas condiciones que adornan al prelado que rige hoy la diócesis de Barcelona."

In an article in early March 1932 Andueza, aware of the latest developments at Ezkioga, detailed the parallels between the Ezkioga visions and the Rafols prophecies, suggesting that the Ezkioga seers and believers were those the Sacred Heart referred to as "just, pure, and chaste souls." And he suggested that the visions and visible miracles the seers expected at Ezkioga were those the Sacred Heart had predicted to Rafols.[20]

Zurbitu, Escritos, 34; LC, 11 March 1932, reprinted in Revista Franciscana (Vic), April 1932, pp. 83-84. This article by Andueza was challenged by Txindor and Or Dago in ED, sparking a polemic with Tomás de Arritoquieta.

Andueza had begun the series to spread the news about Rafols to the Basques. When he mentioned a pamphlet about the Rafols crosses, the Librería Ignaciana in San Sebastián sold all 100 copies of the pamphlet in one hour and 1,000 that week. Andueza obtained excerpts of the second political prophecy from sources at the Vatican. He published them on 10 April 1932, scooping the rest of the country by a month. That issue sold out immediately, with copies going to Barcelona and Zaragoza. When in late May a pamphlet arrived in San Sebastián with the last prophecies, it too sold briskly, 1,500 copies by June 2. One gentleman bought 200 to distribute to friends, and some parish priests purchased as many as 50. For Spain's distressed Catholics the Rafols prophecies, like the Ezkioga visions, were a godsend.[21]

Andueza, LC, 10 April 1932, p. 1; for distribution, LC, 3 June 1932, p. 1. The Rafols prophecies were printed as well in the Mensajero del Corazón de Jesús.

In early May 1932 a prominent doctor drove Andueza with two other priests to Zaragoza. There they saw the holy crucifixes and the site of the document discoveries and spoke to Hermana Naya. Andueza's account of the trip inspired other visits, both from the upper class of San Sebastián and Bilbao ("very prestigious priests, doctors, lawyers, dukes, counts, marquises") and from the community of Ezkioga seers and believers.[22]

LC, 17 May 1932, pp. 1-2, and 26 June 1932, p. 10.

In the end the proponents of the Rafols prophecies had to repudiate the connection with Ezkioga because of the church's rejection of the visions. Domingo de Arrese published a triumphant series of newspaper articles at the height of the Civil War. In them he showed how Madre Rafols had predicted Franco's victory and the reign of the Sacred Heart in Spain for 1940. His book had at least two editions after the war ended. By then the diocese and the Vatican had rejected the Ezkioga visions, so Arrese took care from the start to separate them from Rafols, a clear instance of the pot calling the kettle black: "The case is totally different. Here [with the Rafols revelations] there are no spectacular apparitions, no stigmatizations in which fraud is a possibility."[23]

Arrese, Profecías, 10. Arrese was secretary to the Basque-Navarrese deputies in the Constituent Cortes.