4.

Promoters and Seers II:

the Catalans

From December 1931 through October 1932 Catalan believers in the Virgin of EZkioga played a central part in the visions. Like Antonio Amundarain and Carmen Medina, many brought prior commitments. Some believed the bogus prophecies a nun in Zaragoza was concocting. Others were militants from the movement of a charismatic preacher. Many followed the spiritual directions of a mystic from a small town in Girona.

The immediate interest of the Catalan Catholic bourgeoisie in the apparitions is not surprising. Like Basques and Navarrese, Catalans were especially receptive to new visions because of their proximity to France. In the 1850s Catalans had been attracted to the visions of La Salette; by 1910 they were sending hospital trains on large and regular pilgrimages to Lourdes; and in the years 1919 and 1920 they sent three diocesan pilgrimages to Limpias. Of the Spanish press outside the Basque Country, two Barcelona newspapers gave Ezkioga the best coverage: the Catalanist and centrist El Matí and the Carlist El Correo Catalán . In 1931 El Correo Catalán carried several first-hand

reports by priests; this interest reflected that of the bishop of Barcelona, Manuel Irurita Almándoz.[1]

Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 6-16, 86-87, 150, 191.

The Bishop of Barcelona and the Nun from Zaragoza

Manuel Irurita paid close attention to Ezkioga in part because he was from nearby Navarra and returned every summer to the Valle de Baztán. But perhaps more important was that he, like Antonio Amundarain, had a taste for the marvelous. He was born just over the border from France, and of all bishops up to the Civil War, he was the one who went to Lourdes most frequently.[2]

Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 151. For Irunta's election as bishop of Lleida in 1926, Cárcel Ortí, "Iglesia y estado," 236.

Irurita was not shy about recounting a strange experience of his own. In 1927, when he was a canon in Valencia, he took the wrong train, an express instead of a local, on his way to preach at a Carmelite convent. He prayed for help to Thérèse de Lisieux, and the train jerked to a halt at the station for the convent. When he got off, he asked the engineer what had happened. The engineer said he had seen a nun standing on the tracks. None of the people on the platform had seen her.[3]

Ricart, Un Obispo, 40-41. In Valencia Irurita had been a member of the devotional Escuela de Cristo along with the bishop of Segorbe, who I think was sympathetic to the Ezkioga visions. F. Sánchez Castañer, "Escuelas de Cristo," DHEE 5:254.

Incognito, dressed as a layman, Irurita visited Ezkioga at least four times in 1931. He made his first visit with the priest from Alegia, Pío Montoya, and this may have been around July 21, when Irurita was in Navarra on vacation. His visit on July 31, in the company of Antonio Amundarain, was his third. By then he had had occasion to speak with one of six seers from his native Baztán who had traveled together to Ezkioga; he was impressed with the seer.[4]

N., "Anduaga-mendiko agerpenak [The Apparitions of Mount Anduaga]." Amundarain told the Catalans about the Baztán seer on 14 December 1931 (Gratacós, "Lo de Esquioga," 15-16); a bus from the Baztán valley went to Ezkioga on July 21: PV, 22 July.

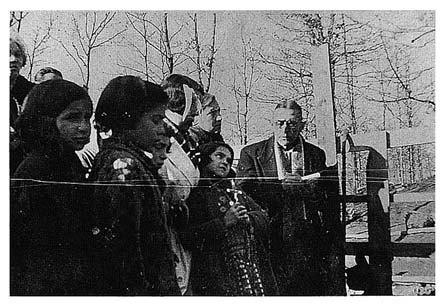

In the aftermath of Ramona Olazábal's wounding Irurita returned to Ezkioga. We see him in photographs kneeling next to Ramona.[5]

The photo in my text, without a caption identifying Irurita, appeared in Antigüedad, Nuevo Mundo, 21 October 1931, and El Nervión, 22 October 1931.

Irurita's last visit to Ezkioga was an open secret and helped to maintain the respectability of the visions at a time when the diocese of Vitoria was turning against them. Pilgrims could buy a souvenir postcard showing Ramona, the Virgin, and Irurita. Irurita subsequently delegated a layman from Barcelona to observe the Ezkioga visions and report back to him. The Barcelona diocesan censor approved articles in favor of the visions for Catholic newspapers as late as the summer of 1932, and at the end of that year Irurita was still saying in private that he believed in the visions.Irurita's prior entanglement in the spurious prophecies of Madre Rafols deepened his interest in Ezkioga. For some time the Sisters of Charity of Saint Anne had been campaigning to canonize their founder, María Rafols y Bruna. The pseudo-Rafols story is a fascinating example of religious politics and merits study.

Rafols was born in 1781 near Vilafranca del Penedès in the province of Barcelona.[6]

For the historic Rafols see Tellechea Idígoras, "Rafols Bruna, Marie," DS 13 (1988), cols. 36-38.

She founded her order in Zaragoza, but it remained small until 1894, when Pabla Bescós became the superior. Bescós obtained approval for the order from Rome and before her death in 1929 organized over sixty new houses, some

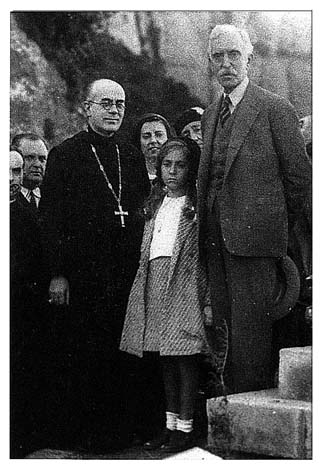

Manuel Irurita, bishop of Barcelona, in civilian clothes watches Ramona Olazábal in vision, 19

or 20 October 1931. Photo by J. Juanes. Courtesy Arxiu Salvador Cardús i Florensa, Terrassa

in South America. In 1932 there were 2,500 religious in 130 houses. As the order grew, its leaders moved to honor their founder. Bescós held meetings in homage to Madre Rafols in Zaragoza and Vilafranca, commissioned a biography, and began gathering documents.[7]

Manuel Graña, "La Madre Rafols," El Debate, 24 May 1932, p. 8; Vida de Pabla Bescós.

In the 1920s Madre Bescós's niece, María Naya Bescós, was a teacher of novices. Perhaps out of a sense of proprietary connection with the order and its history, she began to falsify documents to fill in and illustrate the life of the founder. She made her forgeries with care, using period paper. Her procedure was to observe or provoke contemporary events and have the Sacred Heart of Jesus predict them to Madre Rafols a century earlier. Then she would "discover" the prophecies. For instance, when Naya and the acting superior Felisa Guerri went to purchase the Rafols homestead on 31 August 1924, Naya pointed to a crucifix and identified it as belonging to Madre Rafols. Supposedly the crucifix was fixed to the wall, but Naya was able to remove it with ease, as if she herself had some supernatural power. Later she doctored a prophecy (and discovered it on 2 January 1931) to confirm that the crucifix belonged to Madre Rafols and to

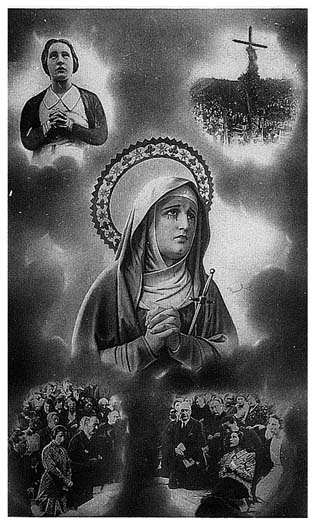

Souvenir postcard of apparitions at

Ezkioga: The Sorrowing Mary, Ramona

Olazábal, and Manuel Irurita, bishop of

Barcelona, October 1931. Photo by J. Juanes.

consecrate its removal as miraculous. This crucifix—El Santo Cristo de la Pureza y Desconsuelo—became an important relic.

María Naya "found" forged letters and spiritual writings in 1922 and between 1926 and 1932. She confirmed her own special role in 1930 by putting into a message from Jesus that the documents would be discovered by "one of [Rafols's] daughters much beloved by my Heart." The prophecies implied that the church would canonize her aunt Pabla as well. On 15 November 1929 workers digging the foundations for a convent at the Rafols homestead found a

second crucifix, allegedly with fresh blood on it. In January 1931 Naya located a prophecy about this crucifix—El Santo Cristo Desamparado—and in October 1931 another about its discovery.

Irurita was named bishop of Barcelona in March 1930 and Vilafranca del Penedès fell within his diocese. On 30 April 1931 he laid the cornerstone for the complex of buildings at Vilafranca. From September 14 through 16 he displayed in his episcopal chapel the crucifix that had "bled" as public atonement for Spain's sins. For long periods he himself held the image for the faithful to kiss. This provoked scenes of religious enthusiasm unusual in Barcelona under the Second Republic. Barcelona Catholic newspapers printed the tales of the miraculous discovery of the crucifixes, and a Barcelona cathedral canon put out a pamphlet. A Zaragoza manufacturer sold copies of El Cristo Desamparado nationwide. Of course, these were trying times for Catholicism and Irurita was acutely aware that the church was no longer one of the powers in control of the nation. In this context a bleeding crucifix meant something special, as did the appearance of the Sorrowing Mother in the Basque hills.[8]

"La Venerable Mare María Rafols," EM, 16 September 1931, p. 2; "La imatge del Crist Desemparat exposada a la Capella de Palau Episcopal," EM, 15, 16, and 17 September 1931, p. 2; and "La imagen del Cristo Desamparado; Piedad consoladora," CC, 17 September 1931, p. 1. Cardinal Pedro Segura dedicated the Vilafranca shrine with three days of prayer in late October 1941, and Esteban Bilbao, minister of justice, said that Irurita had told him about the revelations personally (La Vanguardia Española, 28 October 1941, p. 5). Bilbao said that during his captivity in the Civil War the Rafols prophecies, which presaged "the victory of the sword of Franco," always comforted him. Pamphlet by Barcelona canon is Boada y Camps, Los Crucifijos.

A canon of Zaragoza, Santiago Guallar Poza, was in charge of the Rafols cause. The diocesan tribunal, the first stage in the beatification process, began in July 1926 and finished in February 1927. In 1931 Guallar published a biography of Rafols with the materials he had gathered. That year he was one of eight priests elected to the Constituent Cortes in Madrid. I do not know whether Guallar was aware of the forgeries. But in 1931 politics was on everyone's mind, and Naya began to compose prophecies with a political slant. On 2 October 1931, when the Cortes was about to discuss separating church and state, Naya uncovered a text that included a vision by Rafols of the Sacred Heart predicting visible miracles. And on 29 January 1932, the day the government dissolved the Jesuit order in Spain, Naya found a political prophecy that foretold a chastisement and explained that sacrilege, the removal of the crucifixes, and the expulsion of the Jesuits was the work of the Masons and God's punishment of Spain for female indecency.

The Vatican checked these more political texts and permitted their publication (although the names of the cities God would chastise and the names of living persons were excised). The last prophecy caused a special stir, and Pius XI gave Felisa Guerri and María Naya a second audience. They had already visited him in February 1931 to show the crucifixes. The political prophecies gave the Rafols cult an enormously expanded audience. The texts, in booklets introduced by the Navarrese Jesuit Demetrio Zurbitu, went out by the tens of thousands in early 1932. What started as a pious fraud to make a saint turned into a rally to toughen Spanish Catholics against the secular Second Republic.[9]

The Roman nihil obstats are 1 December 1931 and 27 April 1932. Demetrio Zurbitu (b. Betelu 1886-d. Barcelona 1936) had been director of Marian Congregations in Barcelona: Mècle, "Deux victimes," 6 (I thank Jacques Mècle for letting me consult this unpublished paper). Arrese, Profecías; also López Galuá, Futura grandeza, first ed., 1939.

A commission of experts appointed by the diocese of Zaragoza decided unanimously in January 1934 that the documents were forgeries, but their

finding, since it was part of the beatification process, was kept secret. Clergy who openly questioned the documents included the French Benedictine Aimé Lambert; the preacher Francisco de Paula Vallet; the Dominican Luis Urbano, even more scornful of the Ezkioga visions that he had been of those of Limpias and Piedramillera; and the liturgical scholar Josep Tarré. In the Basque Country Canon Antonio Pildain spoke against the revelations in the cathedral of Vitoria in 1933, and in 1941 Manuel Lecuona, a Basque folklorist from Oiartzun and a former professor at the seminary in Vitoria, published proof of plagiarism.[10]

There was an article ridiculing the Rafols prophecies in EM by P.D., 8 July 1932. Lambert's critical "Los 'escritos póstumos'" was also published in El Bon Pastor, April 1933. I do not know if Eugenio Ferrer published "Los escritos," his rebuttal of Lambert. For Pildain: Juan Bautista Ayerbe to Alfredo Renshaw, 6 October 1933, ASC. Manuel Lecuona, in hiding in a convent of Brígidas in Lasarte, found a source for the forgeries and wrote "Escritos de la M. Rafols." He had been suspicious of their pro-Spanish slant. The Dominican Luis Urbano wrote "Neumann, Rafols" and published Josep Tarré's "Crítica interna." According to Lecuona (Oiartzun, 29 March 1983), Tarré wrote an exposé in several volumes but could not publish it. Francisco de Paula Vallet alerted his friend Josep Pou i Martí in Rome against the prophecies in the summer of 1932. Cardinal Pedro Segura was a prime defender of the prophecies; others included Olegario Corral, Autenticidad, first in Sal Terrae, January 1933, and Castor Montoto, En los escritos. The Zaragoza panel (Mècle, "Deux victimes," 8) consisted of Lambert, the Jesuit scholar Zacarías García Villada, and the director of the Archivo Nacional, Miguel Gómez del Campillo, who later participated in the inauguration of the Vilafranca complex.

After the case reached Rome, in 1943 another panel of experts, including the Catalan Franciscan Josep Pou i Martí, was also unanimously negative. They based their finding on anachronisms, the use of metal pens, the use of the same batch of paper over what was ostensibly a span of forty years, the handwriting, and the outright copying of contemporary literature. The Vatican closed the case, but discreetly, never informing the general public of the fraud. María Naya lost her position with the novices and the order had to withdraw the crucifixes from veneration. But people still read the old books and pamphlets, as well as an occasional new book. Naya, who died in 1966, never spoke on the subject, never admitted her role, and never revealed who, if anyone, worked with her.[11]

Mècle, "Deux victimes," 13, cites Caesaraugustan: Beatificationis ac canonizationis Servae Dei Maria Rafols: Inquisitio super dubio an constat de autenticitate scriptorum (Roma: Polyglotte Vaticane, 1943). For a more recent work see Becker, Tiempo profético.

María Naya hoodwinked Irurita into the Rafols deception by flattery and co-optation, just as she hoodwinked certain Jesuits and even Pius XI. In the message she found 2 January 1931, the last before the messages turned political, Naya had Jesus tell Rafols that "a holy prelate very zealous in the salvation of souls and devoted to his Divine Heart would help my Sisters with his advice and with the other means that [Jesus] would provide him in order to put into practice all the plans of his Divine Heart."[12]

Naya had the Sacred Heart say he wanted the Jesuits to be in charge of all the seminaries in Spain and Pius XI to establish the Feast of Christ the King in the Church Universal (Zurbitu, Escritos, 59-60). Quote from "La Venerable Mare María Rafols," EM, 16 September 1931, p. 2.

Irurita's support was important for the beatification, for Rafols had been born in his diocese. His support was also essential for the new convent and shrine at the homestead site. His personal promotion of the Rafols shrine and the crucifixes demonstrated his total identification with the prelate in the prophecy. Later, to erase any doubt, Naya inserted in the message of 2 October 1931 a reference to the "Lord Bishop who in those years [1931–1940] governs this diocese of Barcelona."[13]Zurbitu, Escritos, 24, message found 2 October 1931.

The belief that he had a providential role to play in Spain's dramatic days sharpened Irurita's interest in the Ezkioga visions. He quickly noticed the convergence of the Basque vision messages and the Rafols prophecies. In the fall of 1931 both predicted visible public supernatural events and by that time both emphasized not Euskadi but Spain. In the Rafols message of 2 October 1931, when the Ezkioga multitudes expected miracles, the Sacred Heart of Jesus said he would, if he had to, save Spain from the devil. He would do so, he said, "with the help of portentous miracles that many people will see with their own eyes; and my Most Holy Mother will communicate to them what they must do to

placate and make amends to my eternal Father." A Catalan correspondent wrote to Ramona about Irurita's attitude toward this vision:

I know that some time ago our Bishop warned your Vicar General to act very carefully since the revelations of the Sacred Heart to M. Rafols ultimately support the cause of Ezquioga. I do not know how he took it. Do not speak of this as it is a sensitive matter.[14]

The Gipuzkoan priest Pío Montoya, who accompanied Irurita to the vision site, remembered that Irurita was at the time seduced by the Rafols prophecies and emphasized their Spanish aspect (San Sebastián, 7 April 1983, p. 16). Quotes from Zurbitu, Escritos, 37, and Cardús to Ramona, 9 March 1932, enclosing Rafols booklets.

The Rafols document of January 1932 warned of a chastisement of Spain which would precede a new age.

This writing will be found when the hour of my Reign in Spain approaches; but before that I will see that it is purified of all of its filth…. [M]y Eternal father will be forced, if they do not reform after this merciful warning, to destroy entire cities.[15]

Zurbitu, Escritos, 56.

Since October 1931 Ezkioga seers had been speaking about chastisements on a grand scale, including the destruction of three Spanish cities. The new Rafols revelation also pointed to a solution—prayer with arms in the form of a cross—that had been in use daily at Ezkioga for seven months by the time Naya produced the message: "The most powerful weapon to win the victory will be the reform of customs and public prayer. The faithful should gather and do petitionary processions and other devotions with their arms in the form of a cross." The Terrassa writer Salvador Cardús noted this similarity immediately and attempted in vain to point it out in the press.[16]

Zurbitu, Escritos, 68; Cardús wrote an article relating Ezkioga and Rafols, "Els fets," by 27 May 1932; both El Matí and Revista Franciscana of Vic rejected the article.

The convergence was not casual. By the time of the last two forgeries, María Naya was clearly aware of what the Ezkioga seers were saying. She and others in the order would have heard from Irurita himself about the visions. And groups of Catalan pilgrims stopped to see her on their way to Ezkioga. One of the group leaders recounted a visit to Zaragoza as follows:

Hermana Naya explained to us the details of her wonderful finds and how she would hear an interior voice that told her to pick up a certain key [to a cabinet or closet], and where and which ones were the writings she was looking for. And then, without our asking her, she expressed her conviction that the Ezkioga matter was certain, that an interior voice affirmed it, although she added prudently that there might exist a small proportion of exaggeration or fiction. And to a question by D. Luis Palà she answered that the interior voice that affirmed to her the reality of the Ezkioga matter was the same, exactly the same, as that which made her pick up a key and find the writings of Madre María Rafols.

In 1932 Naya produced yet another document that confirmed the Ezkioga visions more explicitly. On June 25 she told Ezkioga seers who visited her of a great new revelation, still secret. And on July 12 an Ezkioga enthusiast knew from a Jesuit

friend that "in Rome there is another document of Madre Rafols and that this one is even clearer about Ezquioga. It seems that it will not be made public because it specifies many things and even events of great importance." While these visits and those of high churchmen to Hermana Naya were no doubt in good faith, they bring to mind Leonardo Sciascia's tale Il Consiglio d'Egitto , in which a Sicilian monk lets it be known he has discovered a manuscript of a Moslem history of Sicily and the nobles of the land pay him court and give him presents, hoping to get their families and landholdings mentioned.[17]

Long quote, Bordas Flaquer, La Verdad, 37; for Naya see Boué, 60, 78-79; for Rome see Cardús to Paulí Subirà, Terrassa, 12 July 1932.

Naya and the pseudo-Rafols prophecies in return influenced the Ezkioga visions. When pictures of Rafols began to appear in the souvenir stands at the bottom of the hill, seers began to recognize her. On 1 October 1931 Benita Aguirre had a vision of a nun and later, when given a picture by a Catalan believer, claimed to recognize the nun as Rafols. The visionaries saw Madre Rafols particularly in the spring of 1932, when they were reading booklets and articles about the prophecies.[18]

ARB 104-105; on 25 February 1932 Cardús sent Ramona excerpts from the Rafols October 1931 message and soon after he sent the full message. Ramona replied on March 10: "When I saw these beautiful booklets I showed them to my confessor and he said that everything in them is related to my [vision] declarations." Ramona was reading the Rafols biography by Guallar when she saw Cardús a week later. On May 10 he sent her excerpts from the new, final prophecy and ten days later several copies of the complete text for her and her confessor. Ramona had passed the brochure to Garmendia by June 6, when she wrote Cardús asking for more pictures of Rafols as "everyone wants one." Visions of Rafols in early 1932 included those by Micaela Goicoechea, April 17 (SCD 76-77); Evarista Galdós, April 29 (Rafols reading letter with date of chastisement, B 719); José Garmendia, May 1 (Virgin confirms congruence of revelations and Ezkioga visions, says more documents will appear and that Rafols knew a chapel would be built and the seers persecuted for it, B 634); a Catalan pilgrim, Antonia Quiñonero, in May (ARB 102); and Benita Aguirre, sometime before June 2 (SC D 112). At that time G.-L. Boué was writing both about Rafols and Ezkioga.

In early 1932 the Ezkioga seers had another source of news of the Rafols prophecies, this one close at hand. A priest using the pseudonym Bartolomé de Andueza had written an article about Rafols for La Constancia in 1925. Starting in late February 1932 and ending in late June 1932 he published a series entitled "The Stupendous Prophecies of Madre María Rafols." Andueza seems to have known Irurita. He reported that the bishop had given a woman dying with tuberculosis a picture of Madre Rafols; when the picture touched the woman, it cured her. Referring to the prelate in the Rafols prophecy, Andueza wrote, "Both to you and to me, there comes to mind the very fervent Dr. Irurita, the present bishop of Barcelona."[19]

Andueza, "Luz de lo Alto" and "Las estupendas profecías"; LC, 10 April 1932, p. 1. El Debate made the connection on 23 April 1932: "Se dice que ... prueban algunas condiciones que adornan al prelado que rige hoy la diócesis de Barcelona."

In an article in early March 1932 Andueza, aware of the latest developments at Ezkioga, detailed the parallels between the Ezkioga visions and the Rafols prophecies, suggesting that the Ezkioga seers and believers were those the Sacred Heart referred to as "just, pure, and chaste souls." And he suggested that the visions and visible miracles the seers expected at Ezkioga were those the Sacred Heart had predicted to Rafols.[20]

Zurbitu, Escritos, 34; LC, 11 March 1932, reprinted in Revista Franciscana (Vic), April 1932, pp. 83-84. This article by Andueza was challenged by Txindor and Or Dago in ED, sparking a polemic with Tomás de Arritoquieta.

Andueza had begun the series to spread the news about Rafols to the Basques. When he mentioned a pamphlet about the Rafols crosses, the Librería Ignaciana in San Sebastián sold all 100 copies of the pamphlet in one hour and 1,000 that week. Andueza obtained excerpts of the second political prophecy from sources at the Vatican. He published them on 10 April 1932, scooping the rest of the country by a month. That issue sold out immediately, with copies going to Barcelona and Zaragoza. When in late May a pamphlet arrived in San Sebastián with the last prophecies, it too sold briskly, 1,500 copies by June 2. One gentleman bought 200 to distribute to friends, and some parish priests purchased as many as 50. For Spain's distressed Catholics the Rafols prophecies, like the Ezkioga visions, were a godsend.[21]

Andueza, LC, 10 April 1932, p. 1; for distribution, LC, 3 June 1932, p. 1. The Rafols prophecies were printed as well in the Mensajero del Corazón de Jesús.

In early May 1932 a prominent doctor drove Andueza with two other priests to Zaragoza. There they saw the holy crucifixes and the site of the document discoveries and spoke to Hermana Naya. Andueza's account of the trip inspired other visits, both from the upper class of San Sebastián and Bilbao ("very prestigious priests, doctors, lawyers, dukes, counts, marquises") and from the community of Ezkioga seers and believers.[22]

LC, 17 May 1932, pp. 1-2, and 26 June 1932, p. 10.

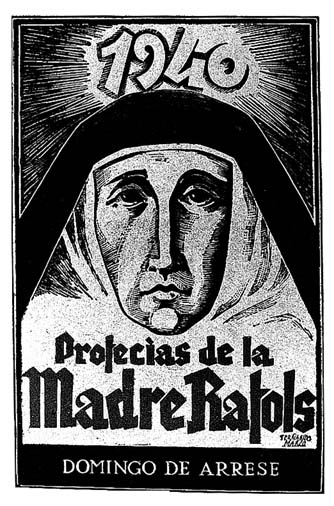

In the end the proponents of the Rafols prophecies had to repudiate the connection with Ezkioga because of the church's rejection of the visions. Domingo de Arrese published a triumphant series of newspaper articles at the height of the Civil War. In them he showed how Madre Rafols had predicted Franco's victory and the reign of the Sacred Heart in Spain for 1940. His book had at least two editions after the war ended. By then the diocese and the Vatican had rejected the Ezkioga visions, so Arrese took care from the start to separate them from Rafols, a clear instance of the pot calling the kettle black: "The case is totally different. Here [with the Rafols revelations] there are no spectacular apparitions, no stigmatizations in which fraud is a possibility."[23]

Arrese, Profecías, 10. Arrese was secretary to the Basque-Navarrese deputies in the Constituent Cortes.

The Terrassa Connection

Other movements of religious enthusiasm in Catalonia found echo and support at Ezkioga. Rafael García Cascón, a wool dealer from Bejar who lived in Terrassa and had access to Bishop Irurita, made one of the first links. According to his daughter and other who knew him, García Cascón was a man of enormous enthusiasms and restless energy. Throughout his long life he dedicated as much time and money to religious excitement as he did to wool.[24]

Montserrat Garcí Cascón Marcet, Terrassa, 19 October 1985.

In Terrassa García Cascón married Vicenta Marcet, daughter and sister of textile moguls. Her uncle, Antonio María Marcet, abbot of the Benedictine monastery of Montserrat, was one of the spiritual leaders of Catalonia. Catholics in Terrassa were proud of their devotion to the Virgin of Montserrat; the devotion explains in part their interest in the visions at Ezkioga.[25]

Cardús, Espiritualitat Monserratina.

Like many militant Catholics worried by Catalonia's social and political plight, García Cascón was active in the Parish Exercises movement of the Jesuit Francisco de Paula Vallet. In the mid-1920s, in an effort to win back lost souls and head off a civil war, el Pare Vallet held hundreds of spiritual exercises for laymen of all social classes. For four or five years Vallet was the most famous preacher in Catalonia; his sermons, some of them broadcast on radio, were blunt and entertaining. Wherever he held missions he set up "Perseverance" chapters to prolong their spiritual effect, thus forming an extensive, self-financed network of laymen. In 1925 García Cascón asked Vallet to give exercises in Terrassa. Subsequently, he was one of Vallet's chief financial backers; he even paid for a trip to the Holy Land for Vallet and two disciples.[26]

Sospedra Buyé, Fa cinquanta anys, 72, and Per carrers, 365.

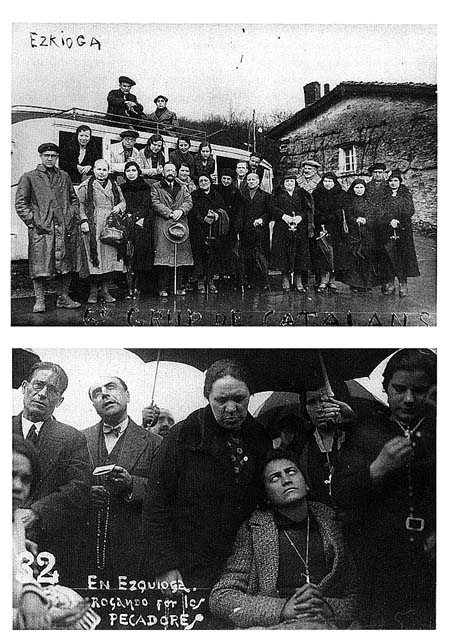

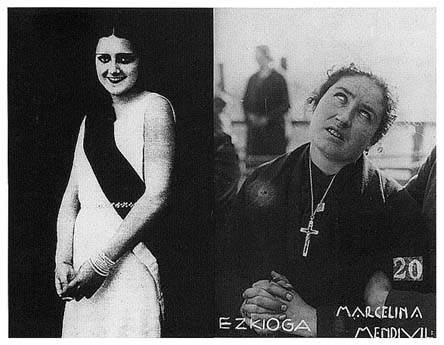

Cover of book relating the Rafols prophecies of the reign

of the Sacred Heart to the victory of Francisco Franco, 1939

Vallet's Parish Exercises movement quickly grew large and powerful. Working largely in Catalan, it spread across diocesan boundaries. And Vallet himself was totally in charge. The Jesuits knew they could not control him. The church hierarchy, especially Cardinal Francesc de Asis Vidal i Barraquer, archbishop of Tarragona, distrusted Vallet's charisma and was afraid he would increase political tensions. And the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera was intransigent when it came to regional nationalism. Vallet first had to leave the Jesuits, then hand over his movement to diocesan and Jesuit control, and finally go into ecclesiastical exile, initially to Uruguay in 1929.

With Vallet in Uruguay, García Cascón went to Ezkioga with his family on 29 August 1931. There he met several of the main seers—the original brother and sister, the girl from Ataun, Patxi Goicoechea, Ramona Olazábal, Juana

Ibarguren, a boy seer from Zumarraga, and Benita Aguirre. A month later García Cascón wrote Vallet from Terrassa about the apparitions and linked them to the inactivity of the Parish Exercises: "Little is being done here. Everything is sort of paralyzed. It is a good thing that God steps in to make up for our weaknesses."[27]

García Cascón to Vallet, 10 October 1931, AHCPCR 10-A-27/3. García Cascón had clients in Legazpi, Mondragón, Tolosa, Rentería, Bergara, and Zumarraga.

García Cascón's most trusted employee was Salvador Cardús. At the time of his employer's letter to Vallet, Card–s was at Ezkioga. This trip began Cardús's long, intense involvement with the Basque visionaries. And thanks to his meticulous archive and his extensive correspondence with the seers, Cardús became one of the great recorders of the entire Ezkioga phenomenon.

The life of this extraordinarily sensitive man encapsulated the political and social tensions of Terrassa and Catalonia at the beginning of the century. For at least eleven years, from 1899 to 1910, his father, Josep, was a weaver in the textile mill of Miquel Marcet. After Salvador's birth in 1900, his mother nursed, along with him, one of the sons of the mill owner. Marcet was implacably pious. He had the Sacred Heart of Jesus enthroned in the workplace and printed on his receipts and he pressured his employees to attend special spiritual exercises. But the weaver Josep Cardús attended the exercises only once and dared to send two of his children to a non-Catholic free school. In 1910 he was the only employee who was a union member. In November of that year a famous freethinking philanthropist and republican politician died in Terrassa, and Catholics and non-Catholics turned out for the civil funeral. Josep Cardús and many other mill workers attended. At this time an adjacent factory was in the midst of a long strike and Marcet feared the weaver might bring the strike to his factory. The mill owner therefore used attendance at the funeral as a pretext to lay Cardús off as a regular employee. A week later the weaver committed suicide, hanging himself prominently from the Vallparadis bridge. At a time of anticlerical and revolutionary fervor, his death became a cause célèbre.[28]

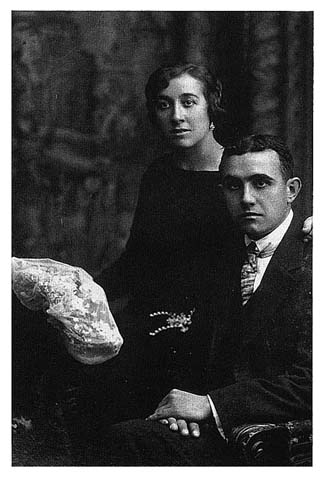

Salvador Cardús i Florensa (1900-1958) married Rosa Grau, October 1924. Biographical information from his sons Oriol, 19 October 1985, and Josep, 27 November 1993, both in Terrassa, and Cardús, "Context biográfic." For the 1910 funeral of Antonio José Toroella and the suicide, see Heraldo de Tarrasa, 24 December 1910, p. 2, and 15 July 1911, pp. 1, 4.

Salvador's mother was pregnant and miscarried when her husband committed suicide. Salvador, aged ten, had to leave school and work in a mill; when he was twelve a carding machine mangled his hand. After four years working in a pharmacy by day and studying by night, he became the assistant to García Cascón, whose wife was the niece of the pious mill owner who had fired Salvador's father, causing his suicide. Extremely devout, Salvador worried about his father's going to hell. Like so many of those who went to Ezkioga, he needed specific news from heaven.

The Ezkioga seers had convinced García Cascón that a great miracle was imminent. And García Cascón sent Cardús to find out when it would be. When Cardús arrived on October 3, he found a crowd of about ten thousand persons in prayer. The Terrassa pilgrims with him made special contact with Ramona Olazábal, her friend from Ataun, and Evarista Galdós. Cardús made a generic request for his family, and Ramona said that when she asked on his behalf, the

Salvador Cardús i Florensa and his wife, Rosa Grau, Terrassa,

October 1924. Courtesy Arxiu Salvador Cardús i Florensa, Terrassa

Virgin smiled in response. Cardús returned to Ezkioga a few days later with the sole purpose of asking about his father. After her afternoon vision Ramona assured him his father was in heaven. Cardús was so happy he wanted to cry. Ramona shared his emotion and sealed a bond with this timid young father of three which lasted for several years.[29]

SC E 26, 30-34, 51-57.

Patxi was then finishing his wooden deck at the vision site and Cardús heard the rumor that the great miracle would take place when the deck was ready. Cardús therefore called his employer to come quickly. García Cascón asked him to stay on and report back. On the night of October 13 Ramona told Cardús in confidence that he should stay until October 15. For then there would take place not the great miracle but a "little" miracle, an advertisement, as it were, for the big one. Cardús learned from the Ezkioga schoolmistress that Ramona had told her that the miracle would consist of receiving something in her hands. The same

teacher had learned from Patxi that the government would learn nothing from the miracles and would imprison him and that there would be a brief holy war in which the Basques saved Spain.[30]

SC E 58-82. On October 13 Ramona had a sad vision, which Cardús attributed to the Virgin's sorrow for the upcoming vote in the Cortes to separate church and state.

On the fifteenth Cardús was present when Ramona's hands bled. That night he could neither eat nor sleep. His friend Ramona, he felt sure, was a saint. Early the next morning he wept in the Zumarraga church: "I was praying with all my soul for the salvation of Catalonia." "So many Catalans," he wrote in his diary, "are coming to Ezquioga and praying fervently and asking the seers to pray for Catalonia, that I have no doubt that the most holy Virgin will listen to their appeals." Cardús asked Ramona if García Cascón should come, and she said "Yes, tell him to come." On that afternoon, October 16, a caravan of private cars carrying about 150 persons left Terrassa for Ezkioga. It arrived the next day, as did sixty thousand other pilgrims, in time to see the minor miracle of the scratch on the hand of the girl from Ataun. Cardús talked to two men from Terrassa who said they saw rosaries hanging in the air before the seer.[31]

SC E 83-93, 98-105, quotes from p. 92.

When Cardús prepared to leave on October 18 after visions at which up to eighty thousand persons were present, García Cascón introduced him to a short, stocky man from Legazpi, José Garmendia.

The Blacksmith and the President of Catalonia

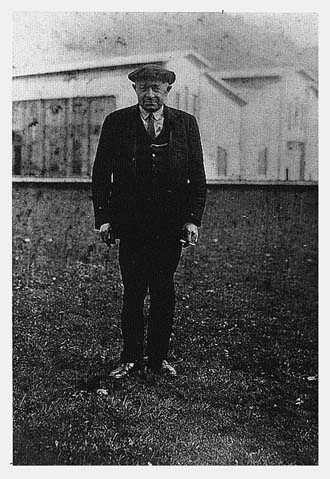

José Garmendia worked in the small foundry of Joaquín Bereciartu in Legazpi. Like many seers, he would have led a life of total obscurity except for the apparitions. Born in Segura in 1893 of an unwed mother, he was thirty-eight years old when he had his first visions at the end of July 1931. The press paid him little heed except to make light of a vision of his mother in purgatory. He was a figure of fun for his neighbors (his heavy drinking did not help), so he convinced few of his experiences. As García Cascón wrote, "He is such a humble man that in his own town no one believes him." In the 1980s few people in Legazpi remembered him by his given name. His nickname was "Belmonte," some said because Belmonte was his favorite bullfighter, others because of the little backward steps, like those of the bullfighter, he would take in his visions. But the Ezkioga believers elsewhere remembered him warmly. A single man, he had few if any local relatives, and in photographs from 1932 he poses with Catalans or with a baker and a real-estate broker from San Sebastián. He seems to have found his family in the community of visionaries. His visions typically included a struggle between good and evil, with the devil acting as a major protagonist.[32]

Garmendia in newspapers, 1931: LC, 25 and 28 July, 2 August; PV, 25 July, 4 August; ED, 28 and 29 July; EM, 8 October. García Cascón to Vallet, 31 October 1931, AHCPCR 10-A-27/2.

When García Cascón met him in mid-October 1931, Garmendia, overshadowed by attractive and convincing youths and children, was still one of the "invisible" seers. But he convinced García Cascón immediately when he said the Virgin had given him a special message to deliver to an important Catalan figure.

José Garmendia in front of factory at Legazpi, 26 October 1931,

shortly after visit to Macià; probably the first photograph of

Garmendia as a seer. Courtesy Arxiu Salvador Cardús i Florensa, Terrassa

This news pleased Cardús and the others from Terrassa but did not surprise them. "It was not strange that the Virgin should have a certain partiality for Catalonia," García Cascón wrote to Vallet, "precisely because so many Catalans had come to this miraculous mountain to pray on behalf of our land."[33]

SC E 117; García Cascón to Vallet, 31 October 1931.

Cardús and the others from Terrassa guessed correctly that the "important figure" in question was the president of the autonomous region of Catalonia, Francesc Macià. García Cascón paid Garmendia's train fare to Barcelona, and on October 23 Cardús accompanied the seer to the office of the president. On being told it was a matter involving the Virgin of Ezkioga, Macià received Garmendia and Cardús at once, then Cardús withdrew, leaving the two to talk alone for fifteen minutes.Garmendia was exhilarated afterward. According to him, Macià had listened with interest as on behalf of the Virgin Garmendia revealed some intimate personal details, warned that life was short, and assured him that he and his sister, a nun, would go to heaven. As Garmendia told it, Macià requested an image of

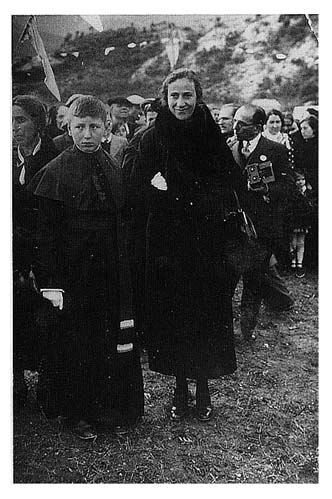

Francesc Macià, president of the autonomous government of Catalonia, at Montserrat the day after José Garmendia's visit. Macià is with his granddaughter and Abbot Marcet, 24 October 1931. Courtesy Arxiu Salvador Cardús i Florensa, Terrassa

the Virgin as she appeared in Ezkioga and asked what he could do. Garmendia asked him to help obtain permission for a chapel on the vision site. Garmendia had wanted a chapel virtually from his first visions in late July. So Macià wrote a note, "Autorizo la construcción de la capilla, Francesc Macià," which Garmendia showed to Cardús. The next day Macià, his wife, daughter, and granddaughter went to Montserrat to open an art exhibit and there he told Abbot Marcet about Garmendia's visit.[34]

Cardús's account in SC E 115-138. El Noticiero Universal, 26 October 1931, p. 7, mentions Macià's close contact with Marcet at Montserrat. See also EM, 21 December 1931.

Garmendia returned to Barcelona on November 14. José María Boada, a wealthy member of the Vallet movement, knew about the previous visit and invited Garmendia back to Barcelona. García Cascón accompanied the seer to Montserrat. There the abbot told them that Macià had spoken at length about Garmendia's first visit, repeating over and over, "I don't know what the Virgin wants me to do." Garmendia quickly observed, "Well, that is what I am here to tell him, what the Virgin wants him to do."

Three days later Macià and his wife received Garmendia in their house, and Macià reportedly asked the seer if the Virgin was happy with him. Garmendia pleased him by answering that she was indeed. Garmendia said he had gone to Madrid the previous month and the Virgin was not so happy with the prime minister, Manuel Azañ, who had refused to receive him. Macià allegedly asked, "So he is worse than I am?" And Garmendia said yes, the Virgin had told him that Azaña would receive the punishment he deserved.[35]

SC E 196-198. For a third visit to Macià, see chap. 6 below.

Garmendia made other visits on behalf of the Virgin. On November 23 he went to see Justo de Echeguren, the Vitoria vicar general, who treated him abruptly. On December 6, this time with García Cascón and Boada, he went back. Echeguren was firm about the matter of Ramona's wounds, and the next day Garmendia claimed the Virgin told him, when he asked her to bless Echeguren, that "the apostles of her son were betraying both her son and her, and they will have to suffer for it later." Garcí Cascón sent the bad news to Echeguren along with prayers for enlightenment.[36]

SC E 205-206, 230-235, 261-263. Undated note [April 1932?] in handwriting of Justo de Echeguren in Laburu papers.

Cardús and his employer kept in touch with Garmendia at least through 1934. Garmendia could barely write, so he dictated his letters. In June 1933 he said he was having fewer visions, only "when the Most Holy Virgin wants me to give some special message." But that fall he was again having visions daily, at home, in bed, outside, or in church. Garmendia did not always convince the Terrassa believers. But for García Cascón and Cardús, he remained a good friend and a valuable connection to heaven.[37]

Garmendia to Cardús, Legazpi, 18 June and 28 October 1933.

Benita Aguirre

During García Cascón's stay at Ezkioga in late October he made another key contact for the Catalans, the child seer Benita Aguirre. Her visions had begun on July 12, two weeks after the first ones at the site. Aged nine, she was the fourth of eight surviving children of Bernarda Odria and Francisco Aguirre, a foreman at the tool foundry in Legazpi. Like many of the seers in the first weeks, Benita sometimes went to Ezkioga with her parish priest. In her vision she saw her stillborn baby brother as an angel near the Virgin. For two weeks she saw but did not hear the Virgin, who on occasion carried a handkerchief embroidered with words. On July 21 El Día introduced her to the public with a summary of her visions, including the Zumarraga doctor Sabel Aranzadi's clinical report:

Benita Aguirre y Odria, born in Legazpi, age nine, with height appropriate for her age, thin, with a pale face, of the neurotic kind; her second teeth are coming in; four years ago she suffered a horizontal nystagmus in one eye, which later disappeared; a year or two ago she suffered a generalized contraction in her entire body which lasted only briefly; she is trusting, not shy, good humored, correctly educated, and she explains herself fluently.[38]

"Los casos observados en Ezquioga por un médico," ED, 21 July 1931, p. 8.

Image removed -- no rights

Benita Aguirre in vision, February 1932. Photo by Raymond de Rigné, all rights reserved.

On July 27 Benita began to hear the Virgin speak. A reporter described her at this time in a characteristic pose:

It is as though she were sleeping, with a smile and with her mouth open, as if marveling. Her eyes look up. Her mother suggests she say some things to the Virgin, and the girl does so without losing her attitude, which is half-surprised and half-joyful.[39]

PV, 31 July 1931, p. 4.

By then observers were singling Benita out as particularly impressive, and she was having visions of a certain complexity. Her vision of August 6 was her sixteenth. The Barcelona Carlist newspaper printed the account she gave to the priests at Ezkioga:

First there appeared in the firmament a hole, then a great brightness came out of it, which when it came above the cross [at the vision site] became concentrated at the feet of the Virgin, who appeared with a black cape and a white bib. The child was dressed in white. Shortly afterward two angels came down with baskets of flowers and arranged themselves at the

feet of the Virgin, one on each side. Shortly after that a man came down with a blue cape crossing from his right shoulder to his left dressed in white. Benita asked spontaneously without anyone prompting her who the man was, and the Virgin replied, "Saint Joseph."

Then Saint Joseph placed himself above the Virgin's head with his hands as one sees in images, but without the lily. Then two white crosses appeared. Then Saint Joseph disappeared. All the people disappeared in the hole in the firmament. The Virgin also disappeared, as did, a little later, the two crosses. The angels circled around and also disappeared.

Note: when the crosses appeared, the angels withdrew so as to leave the crosses placed where they had been.

When the apparition began I asked it, "Ama Maria guk ser egitea nai dezu [Mother Mary, what do you want us to do for you]?" and she replied, "Errezatzea [Pray]."

The Virgin smiled the entire time.

Benita asked for a blessing, and the Virgin shifted the Child from one arm to the other and gave a blessing.[40]

Vision of Benita Aguirre on 6 August 1931 in F. D., CC, 16 August 1931, p. 2.

About the same time a Catalan priest heard Benita recount the following exchange: "My Mother, when will I enter a convent?" "When you are a little older."

About ten days later a canon from Lleida described her as sharp and lively (vivaracha ), and contrasted her correct use of Spanish with that of Patxi. Benita described for him her twenty-sixth vision.

Yesterday [August 16] I saw the Most Holy Virgin with the backs of her hands cut and bloody. She appeared with two swords, one through her heart and the other, with a bloody point, in her left hand. In her right hand she carried a bloody handkerchief. She was dressed in black and wore a crown, which had some long things that gave off light. To her right was Jesus Christ nailed to a cross. When I asked why she had so much blood and if it was for our sins, she answered, "Yes."[41]

Elías, CC, 15 August 1931, vision around 6 August 1931; Altisent, CC, 8 September 1931.

As we have seen, active swordplay was common in the visions at the beginning of August. The heavy emphasis on blood is reminiscent of some of the visions of the Italian mystic Gemma Galgani. Benita's vision prefigured all the imagery for Ramona Olazábal's miracle in October: the bloody backs of hands, the bleeding swords, even the bloody handkerchiefs.

That evening the canon of Lleida Juan Bautista Altisent was next to Benita as she had another vision and he asked her questions while she was rapt. About three hundred persons were present. She saw a variant of her vision the previous night. Six angels carried the bloody swords. Benita moved her lips pronouncing unintelligible words, as if conversing with an invisible person. Altisent asked her what she was saying and hearing, and she said that the Virgin told her she could not tell anyone. Throughout the vision, which lasted a half hour, Benita's mother, at the canon's instructions, lifted her up so that everyone could "admire the

transformation of that little angelic face." At the end the girl stretched out her arms as if trying to catch something going away and said, "Agur Ama [Farewell, Mother]," sadly, three times, "each time with more emotion and reaching out with her little hands as far as she could." Altisent said he had never felt such a strong emotion in his life. Benita told him that Our Holy Mother had been close to everyone, but especially close to him. The child returned to her normal state and dried her tears.[42]

Altisent, CC, 10 September 1931.

Benita's visions after the first couple of weeks moved almost all who saw them. Even a reporter from El Liberal said they made him sad. In 1932 a priest from Barcelona, who was doubtful about much he saw, still wrote of Benita, "Truly it is impossible that a child of nine years could learn to act like that theatrically. The greatest actress after a brilliant career could not do it better. That is admirable." However he could not be sure whether the vision was the work of God or the devil.[43]

Marc Lliró to Cardús, Barcelona, 10 October 1932. The anthropologist Paolo Apolito, glossing a similar comment about an Italian girl, remarks, "If she were [a great actress] nobody would know it" (Dice, 292).

María de los Angeles de Delás from Barcelona heard Benita cry out a wrenching, "Mother, Mother, why are you so sad?" The girl leaned on the woman on the way down the hillside, and Delás noted the tears in her eyes. Like each of these contributors to El Correo Catalán , Delás went away feeling especially connected to the Virgin by personal contact with Benita Aguirre.

After speaking to the child I gave her a kiss, asking her to offer it on my behalf to the Most Holy Virgin, something I saw made her happy, and so we became friends. After that we smiled at each other when our glances crossed, and the next day she would accept the stool I offered for her to sit next to me during the third Rosary.

Here we glimpse the delicate courtship of glances, smiles, and favors constantly at work between the seers and the believers, in this case between a child seer and a believer with notebook in hand.[44]

Delás, CC, 20 September 1931.

At this time—the beginning of September—Rafael García Cascón first met Benita. On his return after Ramona's miracle in late October, his friendship with Benita deepened; he would pick her up, take her to lunch in Zumarraga, drive her to the vision site, and drive her home. He also invited her and her parents to a family gathering at the Hotel Urola in Zumarraga on his saint's day. On his last day Benita had supper and stayed over at the hotel, something he considered "another special favor of the Virgin."[45]

García Cascón to Vallet, 31 October 1931, AHCPCR 10-A-27/2.

One day on the way to Ezkioga García Cascón asked Benita to ask the Virgin whether she was pleased with the work of Vallet and if so to bless him and his disciples. Garmendia overheard the request, and he asked the Virgin about Vallet as well. As García Cascón wrote Vallet, both seers separately said "that the Virgin had said that she was very pleased with what you have done in Catalonia and in South America and that if you continue this way you will have immense glory,

Rafael García Cascón holds a rapt Benita Aguirre on the vision

deck, late October 1931. Courtesy Lourdes Rodes Bagant

and that the Virgin had given her blessing for you and your companions." García Cascón also reported what the Virgin told certain seers about himself and other Catalans:

The Virgin has said that she is very happy for what we have done for Garmendia and that we will be reminded of this. Imagine how pleased this made us, even though we did so little, but the Most Holy Virgin is most grateful.

We also know that the Virgin has said that those who have come from far away, making a great sacrifice and believing in her apparitions, will go to heaven without going through purgatory, and that of these there will be many. From Catalonia have come many people, perhaps more than from anywhere else, taking distance into account.

Benita wrote to García Cascón after his return to Terrassa that the Virgin had told her he should come back as soon as he could. Although only nine, Benita was hardly a passive protégée.[46]

García Cascón to Vallet, 12 November 1931, AHCPCR 10-A-27/1; Benita Aguirre to García Cascón, 24 October 1931, copy in ASC.

In November García Cascón visited Bishop Irurita to relate his experiences

at Ezkioga and tell him about the contact with the Catalonian president, Macià. By then there was great interest in Catalonia. In the fall of 1931 the press carried notices of excursions from Badalona, Calella, l'Espluga Calba, Lleida, Mollerussa, Mataró, Palamós, Reus, Sabadell (at least three trips), Tona (at least two), Torelló, Terrassa (two), and Vic (four). The followers of Vallet, however, organized the most sustained contacts with the visionaries. All Vallet did, far away in Uruguay, was to reprint in the magazine of his movement a newspaper article and a letter from García Cascón. More influential in this respect was Magdalena Aulina of Banyoles.[47]

García Cascón gave lectures about Ezkioga in the textile town of Sabadell, SC E 239, and Barcelona. García Cascón wrote Vallet on 12 November 1931 that he was going to visit Irurita. Vida Interior (Revista Mensual, Organo de la Obra de los Retiros Parroquiales y de las Ligas Parroquiales de Perseverancia, Salto, Uruguay), 2, no. 21 (November 1931): 12-13, and 2, no. 22 (December 1931): 3-4.

Magdalena Aulina, the Mystic from Banyoles

The Vallet followers in Barcelona met in their social center, a downtown mansion known as the Casal Donya Dorotea. There García Cascón lectured on Ezkioga and there early in the previous year another industrialist had brought Magdalena Aulina i Saurina to tell of her miraculous cure and to speak about her new religious society.[48]

For Galgani see Boada, "Flors de santedat"; for the Casal see Sospedra Buyé, Per carrers, 348-359, 423-448, and EM, 1 July 1930.

Developing religious orders drawn into the Ezkioga orbit got a boost of religious enthusiasm. But all came to regret the connection. Magdalena Aulina's institute obtained approval from Rome with great difficulty in 1962, and her successors in the Señoritas Operarias Parroquiales find it difficult to speak about the inspiration of Gemma Galgani and the trips to Ezkioga. They wished me to make clear that the institute existed before the visions at Ezkioga and was quite independent of them.

Magdalena Aulina was born in 1897, the daughter of a wood and coal dealer in the market and summer resort town of Banyoles (Girona). From an early age Magdalena had accompanied her sister, later to become a cloistered Carmelite, in works of charity among the poor. In 1916 she organized a Month of Mary for the children in her neighborhood and later a parish catechism group. By this time she was sure that she had a religious vocation. In part she was inspired by Gemma Galgani, a young woman from Lucca who died at age twenty-five in 1903 after a life dense with mystical phenomena. In 1912 Magdalena read Gemma's biography. In 1921 at age twenty-four Magdalena recovered from a heart condition after a novena to Gemma. This cure confirmed in her mind her spiritual link with the saintly Italian.[49]

Information on Magdalena Aulina i Saurina (b. Banyoles, 12 December 1897-d. Barcelona, 15 May 1956), unless otherwise noted, is from her successor, Filomena Crous, Barcelona, 25 and 27 February 1985, and ephemeral literature she kindly provided, particularly "Discurso de la directora general, bodas de oro del instituto y décimo aniversario de nuestra madre fundadora ... 24 mayo 1966," 17-page typescript.

The early twentieth century was an era of well-publicized miraculous cures at Lourdes. Very early on, the Barcelona pilgrimages prepared clinical dossiers to present to the Lourdes medical commission in case a cure should occur, and the Annales of Lourdes record several cures of Catalans. Those cured became living proof of the Virgin's power and indeed of the existence of God in a doubting world. Miracles invested those cured with charisma. Aulina's cure

Magdalena Aulina with nephew of Gemma Galgani

at the Banyoles "Pontifical Fiesta," at which the first

stone was laid for a monumental fountain to Galgani, 1934

brought her respectful visitors and she told them about Gemma Galgani's help. Banyoles was the headquarters of diocesan parish missioners, and they too spread the word.[50]

Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 13, 163.

The year after Magdalena's cure, in 1922, with the aid of industrialists who were summer residents, she founded a kind of social house in Banyoles for women workers. In 1926 she helped to build a church in her neighborhood and organized a literacy program. She assisted Vallet when he gave parish exercises in Banyoles, and it is possible that he had her in mind to form an order of nuns to assist his movement.[51]

In 1922 Aulina was at Montserrat representing "Patronat d'Obreres de Banyoles" (La IIIa Assemblea de la federació de patronats d'obreres de Catalunya a Monserrat, 1, 2 i 3 d'abril de 1922 [Barcelona: Impremta Editorial Barcelonesa, 1922]).

Aulina had plans of her own, however, and more than enough contacts to put them into practice. At a meeting of Catholic social workers in 1929 at

Montserrat, she met Montserrat Boada, a member of a wealthy Barcelona family with influence in the Vatican. Through the Boadas and similar families, Aulina found support in exactly the same social stratum as Vallet had. When in early 1930 she told Vallet's supporters at the Casal about her spiritual link to Gemma Galgani, she made a deep impression. Shortly afterward José María Boada praised Gemma in the group's magazine, concluding, "Let us let her lead us sweetly through the paths of life."[52]

Boada, "Flors de santedat," 225.

Gemma Galgani seemed to speak through Aulina, who acted more like a spirit medium than a seer. For instance, Cardús was present once at Banyoles when Gemma spoke through Aulina of the future of the institute. Thus, to follow Gemma was in effect to follow Aulina; through Aulina, believers sought Gemma's help in matters both ethereal and mundane.[53]

Aulina's spiritual directors included Angel Soquer, the parish priest of Banyoles; José María Carbó, a canon of Girona; Fulgencio Albareda, a Benedictine of Montserrat; and finally Marcelino Olaechea, a Salesian who was bishop of Pamplona in 1935 and in 1946 archbishop of Valencia.

By 1931 some unmarried young women lived with Aulina in Banyoles fulltime, and three of them took the first private vows of chastity, poverty, and obedience in 1933. On weekends entire families of supporters would come to stay in Magdalena's house, the houses of relatives, hotels, and rented quarters. The supporters were typically doctors, industrialists, and lawyers from Barcelona, Girona (where the group had a clinic), Reus, Terrassa, Sabadell, and Tarragona. Visitors would remark on the sumptuousness of the religious services, with massed choristers in robes and much incense; every Sunday seemed a high feast. Those privileged to dine with Aulina might see her go in and out of trance at the table, as Cardús did, or even watch her in struggle with the devil.

José María Boada helped to persuade Aulina to send regular "expeditions" to Ezkioga. When he heard the praise that seers like Benita passed on from the Virgin about Pare Vallet, he went to Ezkioga to obtain more details. It may be that the seers led Boada to think that he himself had a divine mission; on December 9 Garmendia claimed to see the Virgin on his arm. After Boada reported back to Aulina and Aulina consulted Gemma's spirit, the Casal Donya Dorotea expeditions began on 12 December 1931. Two weeks previously the pope had read in Rome the official proclamation of Gemma's heroic virtues, a stage in the process of beatification, so there was a spate of articles about Gemma in the press which doubtless increased the fervor of Aulina's followers.[54]

SC E 193, 230, 236; Gratacós, "Lo de Esquioga." Gemma Galgani articles, all 1931: EM and CC, 2 December; CC, 11 December; Hormiga de Oro, 17 December; EM, 18 December.

Bartolomé de Andueza, the Rafols enthusiast, was aware of the role of Aulina and Gemma in the trips. In March 1932 he wrote in La Constancia of

the very devout expeditions of Catalans that arrive at Ezquioga weekly to do penance under the patronage of the angelic Gemma Galgani. They were suggested to their organizers by a soul in Barcelona living an extraordinary life who emulates the Italian virgin and has "inherited her spirit."[55]

LC, 11 March 1932.

There were eventually twenty-five trips of twenty-four to thirty persons. All included a lay "director" who led prayers (often Boada) and a technical manager, Luis Palà of the Casal. And, despite the prohibitions of the diocese of Vitoria,

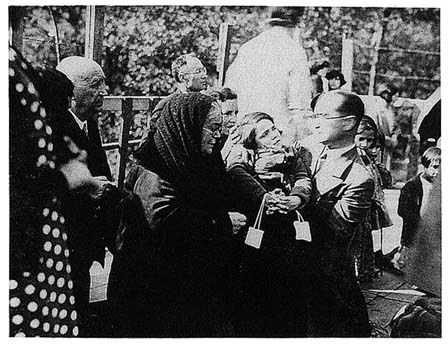

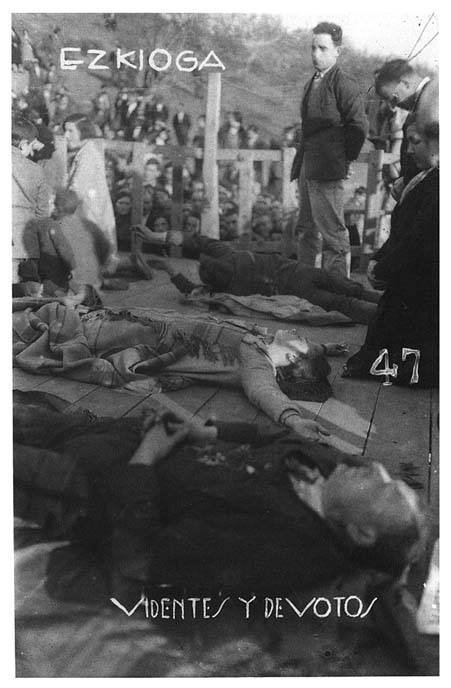

Top:The sixth Catalan expedition to Ezkioga, 8 March

1932; the politician and writer Mariano Bordas holds a hat.

Bottom: José María Broada, with eyes upturned, leads

prayers for sinners, winter 1932. Photos by Joaquín Sicart

there was a priest on most trips. Arturo Rodes Buxados, who went four times, acted on his own as a chronicler. Cardús and García Cascón were not core members of the group, although both for a time became devoted to Aulina-Gemma and both spent periods at the Banyoles complex. The trip took a day and a half each way, and the pilgrims spent four days at the site, staying at the Hotel Urola in Zumarraga. They maintained files of cures and visions and, following the practices of the Parish Exercises movement, posed for group photographs as a public witness of their commitment as Catholics.[56]

I have not seen the documents, now presumably in the Aulina archives. But Burguera included many of them in his book. My other main sources are the manuscript of Arturo Rodes, the diary of Cardús, and the account of the first trip by Luis Gratacós (and José María Boada), "Lo de Esquioga."

The trip members often prayed for as many as eight hours on the hillside, and some evenings for two hours more in the hotel. To outsiders their effusive piety seemed showy. The Piarist priest Marc Lliró of Barcelona watched Boada and Palà lead prayers at Ezkioga and later wrote disapprovingly: "Piety is not ridiculous, or tiresome, or exaggerated, or different from a peaceful normality. At Ezkioga it seemed to me … I found these kinds of false piety."[57]

Marc Lliró to Cardús, Barcelona, 10 October 1932.

Aulina's mysticism spilled over to her followers in other ways. Many of them perceived a perfume on the bus trips and at other significant moments in their daily lives. Often a majority of passengers perceived the scent simultaneously, and to avoid confusion women did not wear perfume or cologne. They understood the scent as a sign of approval from Gemma. For these pilgrims Providence charged every moment of the trip and there was no place for chance. At least a dozen of the six hundred or so expedition members had visions at Ezkioga. Others were converted or cured.[58]Lourdes Rodes, Barcelona, 29 November 1993; B 373-376.

From the start these pilgrims cultivated the seers García Cascón and Boada had come to trust. They would pick them up in the morning and take them to the vision site. There they would have a private vision session. After lunch at the hotel, they would return the seers to the site for late afternoon prayers and then they would take them home. Often seers would also have visions on the bus. The seers quickly incorporated Gemma, as they had Madre Rafols, into their visual repertoire. At the end of October 1931 a Catalan assured the teenage seer Cruz Lete that if he said a novena and promoted devotion to Gemma, she in turn would set things straight at Ezkioga (presumably restore the credibility of the seers, damaged by the Ramona episode). When Lete finished the novena on November 17, he began to see Gemma Galgani in his visions. The Catalans worked to convince the seers that, as Cardús wrote in a letter, "Everything, everything, Ezkioga, Madre Rafols, and Gemma, are all the same thing."[59]

On Cruz Lete see ARB 79, 214. Other visions of Gemma by seers in 1931: Benita Aguirre, December 14, ARB 10; Cruz Lete, December 15, ARB 12-13; María Recalde, December 29. In 1932: Luis Irurzun, February 25; Jesús Elcoro, March 14; Loreto Albo, April 5, ARB 109; Benita Aguirre daily in March and June (Benita to García Cascón, 22 May, and SC D 111-112); Luisa Sabaté in bus, August 24, ARB 115. There were many others from 1933 to 1935. Quote is from Cardús to J. B. Ayerbe, 11 October 1933.

The seers nourished the sense of Providence in these pilgrims. Evarista Galdós predicted that certain of them would have visions, told others they would smell the scent of Gemma, and revealed to a young man his secrets. José Garmendia picked out the only doubter in one group, interceded with the Virgin to remove the devil from one Catalan's visions, and divined the secret prayers of a young Catalan male. On three occasions he pointed out trip members who would be seers.

Garmendia's greatest success was with García Cascón's servant of six years, Carmen Visa de Dios, who went on the trip from 20 to 22 June 1932. Garmendia privately told two trip members that Visa would be a seer and all the members then signed his sealed prediction. The next day while Garmendia was having his vision, Visa had hers. She was a widow, age forty-seven, from Torrente de Cinca (Huesca). Her visions at Ezkioga were of Christ Crucified and the Sorrowing Mother, and for most of the return trip she saw Gemma Galgani hovering like a bird outside or on the hood of the bus. When the pilgrims offered Gemma prayers, Visa saw her nod in response, and as she saw Gemma say farewell on the outskirts of Barcelona, many members said they smelled the Gemma scent.[60]

B 630-635; ARB; SC D. For Visa, SC D 145-174; ARB 114-117; B 635; copy of expedition document, "Visions de Carme Visa de Dios, tingudes els dies 21 y 22 de juny de 1932," 8-page typescript, ASC. Visa had had an earlier vision in Terrassa on 24 October 1931 while her employers were at Ezkioga, and when she returned she had more in the house. She died 10 October 1932.

Benita Aguirre, like Garmendia, interceded for Catalans with the Virgin. From the start she was the group's favorite seer, both because of earlier publicity and because of her message about Pare Vallet. Of the six sessions on the hillside of the first trip, Benita was the central figure in five. Right away the pilgrims invited her to visit Barcelona.

Like previous Catalan observers, the chroniclers of this trip admired her stance in vision. On the afternoon of December 15, as on earlier occasions, the Catalans had given her objects for the Virgin to bless. She laid out the crucifixes in front of her on the vision deck and draped the rosaries on her arms. According to a youth who was present, she then fell face forward and sat up again,

leaning slightly backward, resting in the arms of my friends, her head slightly raised, her eyes fixed on a point high up, but not so fixed that they did not move somewhat or blink occasionally. She speaks with the apparition; she smiles, suffers, sobs, but without tears, asks forgiveness with a sad and tender voice. Then she bends and takes one by one the objects lined in front of her, and each time raising her arm, presents them to the apparition to kiss and bless them. I have a crucifix about a palm long I bought there that Benita held in her hands that afternoon. It was kissed by the Virgin, Gemma (whom she saw again today), and the angels. I also have three red rosaries. The medals on the safety pin I wear were kissed by the Virgin and Gemma. All this as said by Benita.

The youth describing the trip had already stocked up on blessed objects at the two sessions with Benita he attended the previous day. In the morning he had obtained blessings for "three men's rosaries, twenty medals, a miniature image of the Virgin the nuns at Llivia gave me, and a small crucifix that belonged to my mother," all kissed by the Virgin and Gemma. In the afternoon he had "five black rosaries, with smaller beads" kissed by the Virgin, Gemma, and the baby Jesus. He wrote his aunt, "I'll send you some of each." He paid little heed to grand messages of chastisements and miracles scheduled for an indefinite future. As at Limpias a dozen years before, pilgrims were interested in the here-and-now, in resolving spiritual problems and obtaining holy souvenirs.[61]

Gratacós, "Lo de Esquioga," 17-18, 14.

Benita Aguirre raising object to be blessed for Catalans,

ca. 28 February 1932. Photo by Joaquín Sicart

In mid-March Benita went to Barcelona in the group bus and stayed for three days. The group received her enthusiastically at the Casal. And Magdalena Aulina, it seems, enrolled her as a "Servidora de María" in the Obra. At Montserrat the dark Madonna did not impress her. Her Virgin, she said, did not look like that! She stayed with the Rodes family, and Lourdes Rodes, age nineteen, gave Benita her oversize four-foot doll.[62]

ARB 45-46, 245-247; letter from García Cascón to female seer, probably María Recalde, 24 August 1933, private archive; Vitoria Aguirre, Legazpi, 6 February 1986, p. 13. For more on Benita and the Catalans, ARB 48, 89-90, 97-98, 134.

Lourdes Rodes finally got to go to Ezkioga from April 29 to May 4, and there, as Benita's father sheltered them from the rain with an umbrella, she supported Benita in vision. The experience was a spiritual one Lourdes remembered vividly over sixty years later:

Benita was looking upward and speaking in Basque while a man translated and my father took notes. I was filled with an intimate feeling of peace and tranquillity, like a ray of sunlight that warmed me. When the vision went away that feeling stopped. I was left very deeply moved and wanted to cry with happiness.[63]

Lourdes Rodes, Barcelona, 29 November 1993, p. 2.

Later, when Benita could no longer stay in Legazpi, Catalonia proved to be a second home, for she won the hearts of its pilgrims. A clerical observer of an expedition wrote in early October 1932, "I felt sorry for these people who, it seemed to me, believed more in Benita than in the mysteries of the faith."[64]

Lliró to Cardús, Barcelona, 10 October 1932.

Benita Aguirre in vision next to Arturo Rodes with his

notebook, 14 December 1931. Courtesy Lourdes Rodes Bagant.

María Recalde from Durango

María Recalde was another seer the Catalans favored. She was born into a poor rural family in Zenarruza (Bizkaia) in 1894. María could read but could write only her name. She lived in Durango, a clergy-centered town of five thousand. There none of the twenty-six parish priests, none of the Jesuits in the school, and only a handful of the nuns in the five houses believed in her visions. Recalde was one of the few married women to become famous as a seer at Ezkioga. She had had nine children, three stillborn. It was because her first child was born out of wedlock that many local people summarily dismissed her visions.

María's first vision took place on 9 August 1931, just after the intensive newspaper coverage ended. Like Garmendia, Recalde was "invisible" to the press. Only once did a newspaper mention her, although by December 13 she had already had 139 visions. (Counting seems to have been part of the religious ethos; the seers kept score of their visions the same way the Aliadas counted their rosaries and mortifications.) She became well known only after church opposition depleted the ranks of seers and believers.[65]

ARB 7.

She continued to go to Ezkioga for several years. Whether at Ezkioga, at home, or elsewhere, she had visions until her death in 1950. In the 1980s the older generation throughout eastern Bizkaia and the uplands of Gipuzkoa remembered her as a seer.

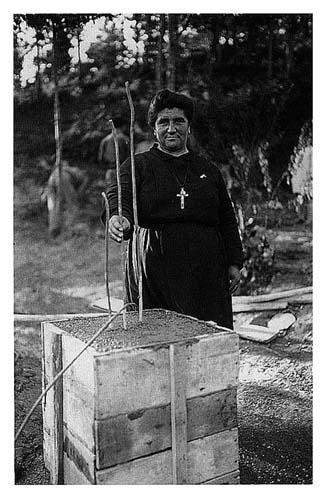

María Recalde with cornerstone of chapel,

spring 1932. Photo by Joaquín Sicart

María Recalde is a particularly engaging character in the Ezkioga story. She had a powerful vitality and combativeness as well as a preternatural shrewdness. She allegedly faced down the judge who interrogated her. She was also warm-hearted and generous. In many photographs she can be seen caring for other seers in vision. She was one of the seers about whom I knew the least until the day her granddaughter Mariví Jayo came to visit me in Las Palmas. Mariví brought with her a tape recording of her father talking about his mother and Ezkioga. Like many families of visionaries, the Jayos had felt the shame of being known as the family of an Ezkioga seer. It was a relief for Lorenzo Jayo to talk about his mother to me when we met subsequently.[66]

Otherwise unattributed information on Recalde is from Lorenzo Jayo in Durango, 31 December 1984, and in Tafira Baja, 15 June 1985.

María's husband was a market gardener supplying milk and fresh vegetables to Durango. María, her son told me, "wore the pants in the family." When in

early August 1931 she began to have visions at Ezkioga and took the train there every afternoon, the family adjusted. With her visions María gained the following of important commercial and manufacturing families in Bilbao and Elorrio, including Manuel and Luisa Arriola, who owned the Artiach cookie company, the Abaytuas, who were stockbrokers, and Matilde Uribe, whose husband owned a steel mill. Like other seers with loyal believers, María supplied these families with news from heaven, some of it obviously convincing. She also developed a following among the rural believers of the Goiherri, the Gipuzkoan uplands; they stood by her until her death.

Starting in November 1931 Recalde and Benita Aguirre began to take people aside and tell them their secret sins as signs from heaven that they should confess, repent, and make their peace with God. The sole newspaper article about Recalde told how she converted one of the souvenir stand operators, Vidal Castillo, by revealing his past sins. This kind of vision became general among the more sociable seers, but it remained Recalde's specialty.[67]

Castillo, ED, 28 November 1931. Francisco Ezcurdia, Ataun, 9 September 1983, pp. 4-5; ARB 57-59, 173; and B 750-751 describe conversions of an Ezkioga cattle dealer, a Catalan pilgrim, and a Barcelona worker; see Surcouf, L'Intransigeant, 19 November 1932: "She has the gift of seeing beings in a state of sin."

Recalde made each of her devotees feel special. For Arturo Rodes she was "the seer most favored by heaven with extraordinary confidences." He was impressed that, like many seers, she knew the date of her death and yet remained calm. He also respected her imperturbability in the face of mockery and slander. Recalde had singled him out; she saw in heaven his two children and four godchildren who were deceased and she promised all would meet him when he died. Similarly, she said the Virgin particularly liked a crucifix that Cardús carried. Another time Recalde picked out from the items Cardús gave her to be blessed a devotional card of Gemma Galgani that included a relic, telling him, "Gemma loves you dearly and considers you her brother." For Cardús, who considered Gemma his spiritual director, this was powerful medicine. Similarly, Recalde in vision informed García Cascón that a crucifix he carried was especially sacred. On his return he installed it in a place of honor in his house, and his visionary servant saw it sweat blood, like the bleeding crucifix of Madre Rafols.[68]

For Arturo Rodes, ARB 72-73; vision of 28 June 1932, ARB 144-145; for Cardús, SC E 410-413, 442-444 (18 and 19 April 1932); for García Cascón, Cardús, "El Sant Crist de la galeria," 8 pages, ASC, with visions of the servant Carmen Visa from 24 June to 1 July 1932 in Terrassa.

María Recalde made the connection with García Cascón and the Catalans during his stays in October 1931. In November she told him that she had seen the Virgin with Madre Rafols and Gemma Galgani together early that month and that the Virgin had said that trips would come with devotees of Gemma from a place where they love Gemma a lot. For this reason García Cascón and his friends thought of María Recalde as a kind of godmother to the Catalan expeditions. María's son winces when he recalls the buses week after week filling the narrow streets of Durango, when the pilgrims came to pick up his mother.[69]

ARB 16-18, 143.

On 8 May 1932 she had a vision in which the Virgin told her where to look for jewels and an image buried in the church of Santa Ana of Barcelona 266 years earlier. And on May 23 she saw not only Gemma Galgani but Magdalena Aulina as well. Two weeks later she went back with a Catalan tripto Barcelona. There she visited Montserrat and the shrine to the souls in purgatory at Tibadabo. On her return to Ezkioga, she claimed, the Sacred Heart of Jesus asked for her hand and, with the Virgin and Gemma Galgani looking on and smiling, pierced it, giving her great joy. Jesus told her that she had much to suffer for Catalonia.[70]

For buried treasure see SC D 78-79; Cardús makes no mention of anyone finding the jewels and image. The contemporary Catalan mystic Enriqueta Tomás also sent followers to dig for treasure, following an old Mediterranean tradition of prophecy; Barcelona trip, 8-11 June 1932, ARB 76; May 23 vision, ARB 143; Sacred Heart vision on June 14, B 603-604.

Women as God's Victims

The Sacred Heart of Jesus piercing María Recalde's hand on behalf of Catalonia points to an ethos of female sacrifice that the Catalan devotees of Rafols and Gemma shared with the Basque seers. Francisco de Paula Vallet had come to believe that, with civil war inevitable, his parish exercises were preparing martyrs, men who would die at the hands of other men. Among Aulina's followers there was a different but complementary program for women. God would take their lives directly. The religiosity of Gemma Galgani, as expressed in the letters and vision texts that Aulina's disciples studied, had as a central premise that people could choose to be victims and stand in for the sins of others. Like Christ, Gemma and Magdalena suffered wounds, the torments of the devil, and illnesses on behalf of the human race. In a key passage from her letters that Cardús cited in his diary, Gemma said Jesus told her:

I have a need for victims, but strong victims to calm the holy and just wrath of my heavenly Father. I need souls to come forward whose sufferings, tribulations, and discomforts make up for the malice and ingratitude of sinners. Oh, if I could only get everyone to understand how indignant my celestial Father is with the world! Nothing is now able to contain his wrath. He is preparing a horrible chastisement against the human race![71]

SC E 534, citing Germán, Cartas y éxtasis, 78.

For Gemma, Aulina, and doubtless many cloistered religious of their day, their willing sacrifice averted a chastisement. As José María Boada described Gemma in 1930, "It pleased Jesus to find in her a true image of his own passion; thus the blessed servant was able to fulfill her sharp desire to make herself like Jesus and suffer for Him."[72]

Boada, "Flors de santedat," 225.

This taste for pain and sacrifice was much in the air. The printed picture of Thérèse de Lisieux in the Ezkioga souvenir stands bore the motto, "Suffering, together with love, is the only thing to be desired in this vale of tears." The mysterious nun known as Sulamitis wrote about "victims of love." At the turn of the century Cardinal Salvador Casañas of Barcelona cultivated "victim souls of Jesus."[73]

Sulamitis, "Victimas de amor," VS, May 1923, pp. 402-404; Monsó, Santidad, 27.